Abstract

Background

Largemouth bronze gudgeon (Coreius guichenoti) is of economic importance in China, distributed in upstream regions of the Yangtze River in China. But it has recently dramatically declined and is close to elimination. However, there is little knowing about the character of its intestinal microbiota. This study was conducted to elucidate the intestinal microbiota of wild largemouth bronze gudgeon with different body weight and gender.

Results

Thirty wild largemouth bronze gudgeon were measured for body length and body weight, and identified for male and female according to gonadal development, and thereafter the intestinal microbiota’s were assessed by MiSeq sequencing of 16S rRNA genes. The results revealed that phyla Proteobacteria and Tenericutes were dominant in wild largemouth bronze gudgeon intestine independent of the body weight. Shannon’s and Inverse Simpson’s diversity indexes were significant (P < 0.05) different between male and female fish. The phylum profile in the intestine of male fish revealed that phylum Proteobacteria was dominant, in contrast to female fish where five phyla Tenericutes, Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria and Spirochaetes were dominant. The genus profile revealed that genera Shewanella and Unclassified bacteria were dominant in male fish, while genus Mycoplasma was dominant in female fish.

Conclusions

Our results revealed that the intestinal microbial community of wild largemouth bronze gudgeon was dominated by the phyla Proteobacteria and Tenericutes regardless of the different body weight, but the communities are significant different between male and female fish. These results provide a theoretical basis to understand the biological mechanisms relevant to the protection of the endangered fish species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Largemouth bronze gudgeon (Coreius guichenoti, Sauvage et Dabry, 1874) is a freshwater fish of the Cyprinidae family, distributed in upstream regions of the Yangtze River. It is of economic importance in China and the largest weight they can reach is 4.0 kg [1, 2]. The fish species is benthic and potamodromous and is typically found in river with torrential flow and they always live in cluster and produce pelagic eggs in flows from March to June every year [3]. However, the species has recently dramatically declined and is close to elimination [4] due to overfishing and construction of hydroelectrically projects, which have blocked the migration routes, causing habitat fragmentation, and losses of spawning grounds and habitat destruction [5, 6].

Over the recent years, the development of omics technologies has boosted our insights on the structure and function of the complex gastrointestinal (GI) microbiota of fish [7–11]. It has been revealed that colonization of microorganisms in the GI tract of fish results in the establishment of a symbiotic relationship between the host and gut microbiota [10, 12], and the fish GI microbiota can contribute to nutrition, health and development [13–15]. In addition, the GI microbiota is important in the defense against adhesion and colonization of pathogenic bacteria [16, 17]. The shaping of the fish intestinal microbiota is a complex process, and a number of factors have been reported to modulate its composition, e.g. host genetics, developmental stage, gut structure, environmental factors, diet and dietary components [10, 12, 18, 19]. However, no information is available on the intestinal microbiota of largemouth bronze gudgeon, a fish species of economic importance in of the Yangtze River.

The ongoing positive growth trend of the ecological protection and species conservation is expected to continue, reflecting the rising demand for largemouth bronze gudgeon rearing in indoor tanks to carry artificial reproduction. Considering the important roles of intestinal microbiota during fish life, the aims of the present study were to elucidate the intestinal bacterial community of wild caught male and female largemouth bronze gudgeon with different body weight from Yangtze River by sequencing of 16S rRNA genes. The evaluation of sex-dependent effects the gut microbiota is of importance to study as less information is available on aquatic animal [20] compared to endothermic animals [21–24]. The results of the present study may be vital for successful propagation of the fish in indoor artificial culture as well as the influence of gender on drug delivery as discussed by Freire et al. [25].

Results

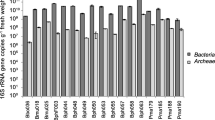

We obtained 963,883 valid sequences from the 30 fish intestines. After quality filtering and normalization; totally 672,240 high-quality bacterial sequences were obtained, equivalent to an average of 22,408 reads per sample, when representative sequences were classified using RDP classifier. We calculated the number of operational taxonomical units (OTUs), and they were analyzed for each sample with a 97 % sequence similarity cutoff value. Figure 1 shows the rarefaction curve at an OTU definition of 97 % identity. The Good’s coverage of the four samples ranged from 99.70 to 99.86 % (Table 1).

Intestinal microbial community in fish with different body weight

To provide an overview of the sequence reads associated with wild caught largemouth bronze gudgeon intestine, the 30 samples were divided into three groups according to fish body weight: large fish (>2 kg, 4 samples), medium fish (between 1 and 2 kg, 17 samples) and small fish (<1 kg, 9 samples). In small fish, the Shannon and Inverse Simpson diversity indexes were 0.38 ± 0.21 and 0.21 ± 0.14, respectively, while the indexes were somewhat higher, but not significantly (P >0.05) different for medium - and large fish (Fig. 2).

The bacterial communities of the intestines from all samplings constituted of totally 18 different bacterial phyla, of which seven phyla were dominant, and represented 99.8 % of the entire sequence reads (Fig. 3a). Bacteria within phylum Proteobacteria was dominant in the intestine of wild caught largemouth bronze gudgeon and constituted for 68.4 % ± 29.2 in small fish, and 71.0 % ± 20.8 and 86.3 % ± 10.9 in medium- and large fish, respectively. The abundance of phylum Tenericutes was 28.4 % ± 19.3 in small fish; 24.1 % ± 18.2 and 11.7 % ±10.7 in medium - and large fish, respectively. The remaining five phyla: Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria and Spirochaetes constituted for less than 2 % of the total bacterial community of all fish. Gammaproteobacteria was dominant; 63.6 % ± 27.4 in small fish; 62.9 % ± 31.9 and 85.0 % ± 13.5 in medium - and large fish, respectively (Fig. 3b).

Intestinal microbial community in different gender

Twenty sexual mature individuals were identified in the present study, 10 male and 10 female, and they were analyzed to compare their microbial community profile. Shannon’s and Inverse Simpson’s diversity indexes in male fish were 0.14 ± 0.09 and 0.05 ± 0.03, respectively, while the indexes were significantly (P < 0.001) higher in female fish (Fig. 4). DCA and PCoA ordination respectively based on the microbial compositions and weighted UniFrac distances revealed that male and female fish harbored different intestinal microbial community (Fig. 5).

16S rRNA gene sequence reads analysis revealed that the bacterial community composition was different between female and male fish. In the intestines of male fish, the dominant phylum Proteobacteria constituted 97.6 % ± 1.8 of the microbiota, while the other phyla constituted less than 2.5 % of all reads (Fig. 6). In female fish intestines, phyla Tenericutes and Proteobacteria were dominant, accounting for 52.3 % ± 23.5 and 40.5 % ± 22.8, respectively. Phyla Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, Spirochaetes, Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes were also identified, and constituted for 2.4 % ± 1.2, 1.9 % ± 1.5 and 1.7 % ± 1.3, 0.4 % ± 0.2 and 0.6 % ± 0.5, respectively (Fig. 6).

Intestinal genera in fish with different gender

The five most abundant genera in male and female fish intestines are shown in Table 2. The total abundance of these genera relative to the total amount of reads was 91.1 % ± 7.64 for male fish and 87.4 % ± 10.2 for female fish. The dominant genus in male fish was unclassified bacteria and constituted for 34.9 % ± 11.3 of the entire reads with non-significant difference to female fish. In male fish, unclassified bacteria belonging to phylum Proteobacteria and family Enterobacteriaceae were dominant and comprised of approximately 75 % of the bacterial community. Genus Mycoplasma (52.3 % ± 24.8) belonging to phylum Tenericutes dominated in female fish intestine, but the relative abundance significantly (P < 0.01) decreased to 0.98 % ± 0.35 in male fish. The abundance of genera Aeromonas and Pseudomonas, both belonging to phylum Proteobacteria were not significant different between male and female fishes. However, the abundance of genus Shewanella (phylum Proteobacteria) was significantly (P < 0.05) higher in male fish intestine than that in female fish.

Discussion

Previous studies on largemouth bronze gudgeon, a Cyprinidae, have focused on its genetic diversity and stress responds [4], while no information is available on the intestinal microbiota. This topic needs to be evaluated as the intestinal microbiota of endothermic animals as well as fish plays a crucial role to the host [12, 26], and knowledge of the intestinal microbiota and its modulation in largemouth bronze gudgeon may be of importance to understand wild fish viability under cultured conditions as reported for sea bream (Sparus aurata) [27].

The non-significant difference in bacterial diversity by the Shannon and Inverse Simpson diversity indexes between fish with different body weight (>2 kg, 1–2 kg and <1 kg), indicate that different fish body weights had no effect on intestinal microbiota of largemouth bronze gudgeon; probably due to similar habitats.

In a study with common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.), Li et al. [28] reported a core gut microbiota of Fusobacteria, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes but this is inconsistent with the core gut microbiota: Proteobacteria and Tenericutes of largemouth bronze gudgeon revealed in the present study, although the fish species belong to the same family; omnivores and benthic life. One possible reason for this difference may be that largemouth bronze gudgeon is omnivores but prefer animal food in nature environment contradict to common carp [29]. It is reported that the intestinal microbiota associated with host trophic level, and the intestinal bacterial diversity decrease in herbivores to omnivores to carnivores’ fish species [30–32].

The intestinal bacterial community between male and female largemouth bronze gudgeon was different in the present study, which is in accordance with Iehata et al. [20], revealing difference in both bacterial community and bacterial nutritional enzyme activity between female and male Chilean octopus (Octopus mimus). Moreover, endothermic animals studies have also revealed that the gut microbiota composition between gender are different [21–24, 33]. The difference in gut microbiota between sexes, may be hormones associated with each sex that might affect the composition of the gut microbiota [34, 35]. Different feed preference may be another reason for the variations in the intestinal microbiota, as the fish were sampled during different month during the season. In addition, the water temperature may influence the feeding behavior and gut microbiota. However, male and female fish sampled from different sampling times showed no variations within group in the present study. In their review, Freire et al. [25] discussed the influence of gender on gastrointestinal physiology and drug delivery. Whether the results of the present study may be of importance for drug delivery in fish is not known and merits investigation.

Intestinal bacteria can serve the host in two ways: they can represent a nutrient source and/or contribute with enzymes that may improve host digestion [13, 36]. Previous studies, revealed that some strains of genera Aeromonas and Pseudomonas produced amylase efficiently in freshwater fish, and this finding suggest that the intestinal microbiota may play an important role to the host [37]. In the present study, the genera Aeromonas and Pseudomonas were dominant in male and female largemouth bronze gudgeon, but no significant difference was revealed. Whether these bacteria species contribute to the fish nutrition is a topic for further investigation.

It is of interest to note that the most dominant genus in male and female largemouth bronze gudgeon was unclassified bacteria (phylum Proteobacteria and family Enterobacteriaceae) and Mycoplasma (phylum Tenericutes), respectively, which is different to the findings reported for other freshwater fish species [28, 38]. Ringø et al. [9] showed that the abundance of Enterobacteriaceae were affected by protein sources. This may be of interest as some members of Enterobacteriaceae have been reported to benefit metabolic activity; saccharolytic and utilizing acetate, while other members of the family are potentially opportunistic pathogens [39]. Whether the protein sources for male and female fish development were different and what’s the function of these unclassified bacteria merit further investigation. Genus Mycoplasma is reported as pathogens for human, animals and plants [40]. However, Holben et al. [41] detected a novel Mycoplasma phylotype which comprised for approximately 96 % of the total microbes in the distal intestine of wild Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.), which were substantially different from those indicated in pen-raised salmon from Scotland and Norway. Moreover, the authors speculate the Mycoplasma species could utilize cytoplasmic secretions from the host and produce lactic and acetic acids which subsequently utilized by other bacteria in wild salmon intestine. Considering the significantly (P <0.01) increase in abundance of genus Mycoplasma in female largemouth bronze gudgeon, some special metabolic activity may exist in female fish.

Genus Shewanella, which have been isolated from marine environments [42], were detected at a significantly (P <0.05) higher abundance in male largemouth bronze gudgeon in the present study. This finding may be of importance as several strains of genus Shewanella have previously been reported to produce polyunsaturated fatty acids [43]. As the predominant genera in largemouth bronze gudgeon were more similar to Atlantic salmon than common carp, similar family as largemouth bronze gudgeon, this topic requires further evaluation.

Conclusion

The present study revealed that the intestinal microbial community in wild largemouth bronze gudgeon sampled from the Yalong River, had a core intestinal microbiota: phyla Proteobacteria and Tenericutes regardless of different body weight. In addition, it is of interest to notice that difference occurs in the intestinal bacterial community between male and female fish, which may due to the various metabolic activities in male and female fish. The results of the present study increase our understanding of the microbial ecosystem diversity in an endangered fish species. Furtherly, understanding the associations between the structure and function of intestinal bacterial communities and body ecosystem parameters is important for determining the fish’s physical condition, and such information will also contribute to optimize breeding regimes and improve the health of endangered fish species in captivity.

Methods

Fish of the study

During April, June and fall (October-November) 2013, 30 wild largemouth bronze gudgeon were sampled from the Yalong River, the upper reaches of the Yangtze River (Yanbian county). The fish were placed in oxygen filling box, transported to the laboratory on ice, and measured for body length and body weight. Male and female fish were identified according to gonadal development.

Sample collection

All fish were anesthetized with an overdose of MS 222 (3-Aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester methanesulfonate, Sigma, Germany). The exterior surfaces were swabbed with 75 % ethanol before dissection of the whole intestine using sterile instruments (scissors and tweezers). The intestine of each individual fish was dissected out, and similar weight (about 0.2 g) of foregut, midgut and hindgut from each individual was collected and pooled together into a sterile tube as a single sample as described previously [38]. The individual intestinal contents were homogenized by vortexing briefly.

DNA extraction

DNA preparation was performed by incubating intestinal homogenates in 1 ml lysis solution (30 mmol l−1 EDTA, 10 mmol l−1 Tris-HCl, 0.5 % sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), 0.1 mg proteinase K, 0.05 mg RNase A) overnight at 55 °C, followed by standard phenol/chloroform extraction as previously described [44]. DNA solution was stored at −20 °C until further use.

MiSeq sequencing of bacterial 16S rRNA gene amplicons

Liu et al. [45] reported that the V4 region shows few biases for different bacterial taxa, and the region is considered to yield accurate taxonomic information. Therefore, the V4 region of 16S rRNA gene was used in the present study to assess the fish intestinal bacterial community. PCR amplifications were performed in triplicate with the bacterial primer sets 515 F/806R [46], PCR products were purified using Agencourt® Ampure® XP beads (Beckman, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purified DNA was then used as a template to perform a second PCR using the same primer sequences and the protocol, but the reverse primer sequence included appropriate adapters and different barcodes for the identification of samples. PCR products were visualized on 1 % agarose gels and negative controls were performed each time to ensure that no contamination had occurred.

PCR products were quantified using the PicoGreen dsDNA Assay kit (Invitogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), equally combined and followed by gel purification using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, CA, USA), and then re-quantified by PicoGreen. The prepared DNA library was then sequenced using the MiSeq platform (Illumina, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Quality filtering and processing of sequence reads were conducted on Galaxy pipeline (http://zhoulab5.rccc.ou.edu:8080/root) as described previously [47]. An OTU table was generated using the Uparse clustering method (97 % cutoff), and all samples were rarefied to the same sequencing depth by resampling OTUs prior to downstream analysis.

Statistical analysis

The representative sequence of each OTU was used for taxonomy assignment using Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) classifier [48]. In order to compare the bacterial communities, good’s coverage and alpha-diversity indices were calculated according to the procedures described by Caporaso et al. [49]. Alpha- measurements were applied to describe species composition in one specific habitat and the differentiation among habitats, respectively according to Peter et al. [50]. Detrended correspondence analysis (DCA) and UniFrac distance-based PCoA analyses were also performed to visually depict the differences between male and female fish. One way ANOVA and two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to assess the differences of intestinal bacterial communities between male and female fishes. Statistical analyses were performed with the software PASW SPSS 18.0 (IBM, USA) and R 3.2.0 (Lucent Technologies, USA) package.

References

Liu LH, Wu GX, Wang ZL. Reproduction ecology of Coreius eterodon and Coreius guichenoti in the mainstream of the Changjiang River after the constructions of Gezhouba Dam. Acta Hydrobiol Sin. 1990;14:205–15.

Liao X, Yu X, Chang J, Tong J. Polymorphic microsatellites in largemouth bronze gudgeon (Coreius guichenoti) developed from repeat- enriched libraries and cross-species amplifications. Mol Ecol Notes. 2007;7:1104–7.

Zhang F, Tan D. Genetic diversity in population of largemouth bronze gudgeon (Coreius guichenoti Sauvage et Dabry) from Yangtze River determined by microsatellite DNA analysis. Gen Genet Syst. 2010;85:351–7.

Zhao JH, Zhu YJ, He YF, Chen JW, Feng XB, Li X, Xiong BX, Yang DG. Effects of temperature reduction and MS-222 on water quality and blood biochemistry in simulated transport experiment of largemouth bronze gudgeon, Coreius guichenoti. J World Aquacult Soc. 2014;45:493–507.

Chen DQ, Liu SP, Duan XB, Xiong F. A preliminary study of the fisheries biology of main commercial fishes in the middle and upper reaches of the Yangtze River. Acta Hydrobiol Sin. 2002;26:618–22.

Duan XB, Chen DQ, Liu SP, Chi CG, Yang RH. Studies on status of fishery resources in Three Gorges reservoir reaches of the Yangtze River. Acta Hydrobiol Sin. 2002;26:605–11.

Navarrete P, Espejo R, Romero J. Molecular analysis of microbiota along the digestive tract of juvenile Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Microb Ecol. 2009;57:550–61.

Roeselers G, Mittge EK, Stephens WZ, Parichy DM, Cavanaugh CM, Guillemin K, Rawls JF. Evidence for a core gut microbiota in the zebrafish. ISME J. 2011;5:1595–608.

Ringø E, Zhou Z, Olsen RE, Song SK. Use of chitin and krill in aquaculture–effect on gut microbiota and the immune system: A review. Aquacult Nutr. 2012;18:117–31.

Ringø E, Zhou Z, Vecino JLG, Wadsworth S, Romero J, Krogdahl Å, Olsen RE, Dimitroglou A, Foey A, Davies S, Owen M, Lauzon HL, Løvmo Martinsen L, De Schryver P, Bossier P, Sperstad S, Merrifield DL. Effects of dietary components on the gut microbiota of aquatic animals: a never-ending story? Aquacult Nutr. 2016;22:219–82.

Zhou Z, Yao B, Romero J, Waines P, Ringø E, Emery M, Liles MR, Merrifield DL. Methodological approaches used to assess fish gastrointestinal communities. In: Merrifield D, Ringø E, editors. Aquaculture nutrition: gut health, probiotics and prebiotics. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing; 2014. p. 101–27.

Nayak SK. Role of gastrointestinal microbiota in fish. Aquacult Res. 2010;41:1553–73.

Ray AK, Ghosh K, Ringø E. Enzyme-producing bacteria isolated from fish gut: a review. Aquacult Nutr. 2012;18:465–92.

Bakke I, Skjermo J, Vo TA, Vadstein O. Live feed is not a major determinant of the microbiota associated with cod larvae (Gadus morhua). Env Microbiol Rep. 2013;5:537–48.

Llewellyn MS, Boutin S, Hoseinifar SH, Derome N. Teleost microbiomes: the state of the art in their characterization, manipulation and importance in aquaculture and fisheries. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:207.

Cheesman SE, Guillemin K. We know you are in there: conversing with the indigenous gut microbiota. Res Microbiol. 2007;158:2–9.

Fraune S, Bosch TCG. Why bacteria matter in animal development and evolution. Bioessays. 2010;32:571–80.

Lauzon HL, Gudmundsdottir S, Petursdottir SK, Reynisson E, Steinarsson A, Oddgeirsson M, Bjornsdottir R, Gudmundsdottir BK. Microbiota of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua L.) rearing systems at pre and posthatch stages and the effect of different treatments. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;109:1775–89.

Navarrete P, Magne F, Araneda C, Fuentes P, Barros L, Opazo R, Espejo R, Romero J. PCR-TTGE analysis of 16S rRNA from rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) gut microbiota reveals host-specific communities of active bacteria. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31335.

Iehata S, Valenzuela F, Riquelme C. Analysis of bacterial community and bacterial nutritional enzyme activity associated with the digestive tract of wild Chilean octopus (Octopus mimus Gould, 1852). Aquacult Res. 2015;46:861–73.

Mueller S, Saunier K, Hanisch C, Norin E, Alm L, Midtvedt T, Cresci A, Silvi S, Orpianesi C, Verdenelli MC, Clavel T. Difference in faecal microbiota in different European study populations in relation to age, gender, and country: a cross-sectional study. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:1027–33.

Zwielehner J, Lassi C, Hippe B, Pointer A, Switzeny OJ, Remely M, Kitzweger E, Ruckser R, Haslberger AG. Changes in human fecal microbiota due to chemotherapy analysed by TaqMan-PCR, 454 sequencing and PCR-DGGE fingerprinting. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28654.

Deusch O, O’Flynn C, Colyer A, Swanson KS, Allaway D, Morris P. A longitudinal study on the feline faecal microbiome identifies changes into early adulthood irrespective of sexual development. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144881.

Shastri P, McCarville J, Kalmokoff M, Brooks SPJ, Green-Johnson JM. Sex differences in gut fermentation and immune parameters in rats fed an oligofructose-supplemented diet. Biol Sex Diff. 2015;6:13.

Freire AC, Basit AW, Choudhary R, Piong CW, Merchant HA. Does sex matter? The influence of gender on gastrointestinal physiology and drug delivery. Int J Pharmaceut. 2011;415:15–28.

Sekirov I, Finlay BB. The role of the intestinal microbiota in enteric infection. J Physiol. 2009;587:4159–67.

Kormas KA, Meziti A, Mente E, Frentzos A. Dietary differences are reflected on the gut prokaryotic community structure of wild and commercially reared sea bream (Sparus aurata). Microbiologyopen. 2014;3:718–28.

Li XM, Yan QY, Xie SQ, Hu W, Yu YH, Hu ZH. Gut microbiota contributes to the growth of fast growing transgenic common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). PLoS One. 2013;8:e64577.

Liu F, Dan SG, Wang JW, Cao WX. Feeding habits of Coreius guichenoti (Sauvage et Dabry) in the upper Yangtze river. Acta Hydrobiol Sin. 2012;36:1081–6.

Ward N, Steven B, Penn K, Methe B, Detrich W. Characterization of the intestinal microbiota of two Antarctic notothenioid fish species. Extremophiles. 2009;13:679–85.

Wong S, Rawls JF. Intestinal microbiota composition in fishes is influenced by host ecology and environment. Mol Ecol. 2012;21:3100–2.

Li ZM, Xu L, Liu WX, Liu YC, Ringø E, Du ZY, Zhou ZG. Protein replacement in practical diets altered gut allochthonous bacteria of cultured cyprinid species with different food habits. Aquacult Int. 2015;23:913–28.

Ding T, Schloss PD. Dynamics and associations of microbial community types across the human body. Nature. 2014;509:357–67.

Markle JGM, Frank DN, Mortin-Toth S, Robertson CE, Feazel LM, Rolle-Kampczyk U, von Bergen M, McCoy KD, Macpherson AJ, Danska JS. Sex differences in the gut microbiome drive hormone-dependent regulation of autoimmunity. Science. 2013;339:1084–8.

Yurkovetskiy L, Burrows M, Khan AA, Graham L, Volchkov P, Becker L, Antonopoulos D, Umesaki Y, Chervonsky AV. Gender bias in autoimmunity is influenced by microbiota. Immunity. 2013;39:400–12.

Clements KD, Angert ER, Linn Montgomery W, Howard CJ. Intestinal microbiota in fishes: what’s known and what’s not. Mol Ecol. 2014;23:1891–8.

Sugita H, Kawasaki J, Deguchi Y. Production of amylase by the intestinal microflora in cultured freshwater fish. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1997;24:105–8.

Li XM, Zhu YJ, Yan QY, Ringø E, Yang DG. Do the intestinal microbiotas differ between paddlefish (Polyodon spathala) and bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis) reared in the same pond? J Appl Microbiol. 2014;117:1245–52.

Wu SG, Tian JY, Wang GT, Li WX, Zou H. Characterization of bacterial community in the stomach of yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco). World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;28:2165–74.

Piersimoni C, Scarparo C. Extrapulmonary infections associated with nontuberculous mycobacteria in immunocompetent persons. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1351–8.

Holben WE, Williams P, Gilbert M, Saarinen M, Särkilahti LK, Apajalahti JH. Phylogenetic analysis of intestinal microflora indicates a novel Mycoplasma phylotype in farmed and wild salmon. Microb Ecol. 2002;44:175–85.

Kim KK, Kim YO, Park S, Kang SJ, Nam BH, Kim DN, Oh TK, Yoon JH. Shewanella upenei sp. nov., a lipolytic bacterium isolated from bensasi goatfish Upeneus bensasi. J Microbiol. 2011;49:381–6.

Hirota K, Nodasaka Y, Orikasa Y, Okuyama H, Yumoto I. Shewanella pneumatophori sp. nov., an eicosapentaenoic acid-producing marine bacterium isolated from the intestines of Pacific mackerel (Pneumatophorus japonicus). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:2355–9.

Li XM, Yu YH, Feng WS, Yan QY, Gong YC. Host species as a strong determinant of the intestinal microbiota of fish larvae. J Microbiol. 2012;50:29–37.

Liu ZZ, Lozupone C, Hamady M, Bushman F, Knight R. Short pyrosequencing reads suffice for accurate microbial community analysis. Nuc Acids Res. 2007;35:e120.

Bates ST, Berg-Lyons D, Caporaso JG, Walters WA, Knight R, Fierer N. Examining the global distribution of dominant archaeal populations in soil. ISME J. 2011;5:908–17.

Yan QY, Li JJ, Yu YH, Wang JJ, He ZL, Van Nostrand JD, Kempher ML, Wu LY, Wang YP, Liao LJ, Li XH, Wu S, Ni JJ, Wang C, Zhou JZ. Environmental filtering decreases with fish development for the assembly of gut microbiota. Environ Microbiol. 2016; doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13365.

Cole JR, Chai B, Marsh TL, Farris RJ, Wang Q, Kulam SA, Chandra S, McGarrell DM, Schmidt TM, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM. The ribosomal database project (RDP-II): Previewing a new autoaligner that allows regular updates and the new prokaryotic taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:442–3.

Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Lozupone CA, Turnbaugh PJ, Fierer N, Knight R. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4516–22.

Peter H, Beier S, Bertilsson S, Lindström ES, Langenheder S, Tranvik LJ. Function-specific response to depletion of microbial diversity. ISME J. 2011;5:351–61.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge to Yongjiu Zhu, Jianhua Zhao and Zhijun Shu for their helps in catching the experimental fish. We acknowledge to Jiajia Ni for helping the data analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by the Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest (201203086-02), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31502142) and the Foundation of China Three Gorges Corporation (JGJ/025 2013).

Availability of data and materials

All sequencing data has been deposited in the sequencing repository: NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA). The bioproject accession, biosample_accession and sequence read archive (SRA) accession are PRJNA336479, SAMN05511397 and SRP080975, respectively. SRA records is accessible with the following link: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/SRP080975.

Authors’ contributions

XL collected the samples, performed data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. QY performed MiSeq sequencing of 16S rRNA genes. ER helped to improve the manuscript and participated in data analysis. XW and YH collected the samples, performed physical analyses. DY supervised this project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The collection, preservation and research of wild animal and endangered species are approved by national regulations “China biodiversity conservation strategy and action plan”.

All experiments involving animals were performed under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Approval ID: keshuizhuan 08529).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Yan, Q., Ringø, E. et al. The influence of weight and gender on intestinal bacterial community of wild largemouth bronze gudgeon (Coreius guichenoti, 1874). BMC Microbiol 16, 191 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-016-0809-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-016-0809-1