Abstract

Background

So far, biocontrol agent selection has been performed mainly by time consuming in vitro confrontation tests followed by extensive trials in greenhouse and field. An alternative approach is offered by application of high-throughput techniques, which allow extensive screening and comparison among strains for desired genetic traits. In the genus Trichoderma, the past assignments of particular features or strains to one species need to be reconsidered according to the recent taxonomic revisions. Here we present the genome of a biocontrol strain formerly known as Trichoderma harzianum ITEM 908, which exhibits both growth promoting capabilities and antagonism against different fungal pathogens, including Fusarium graminearum, Rhizoctonia solani, and the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. By genomic analysis of ITEM 908 we investigated the occurrence and the relevance of genes associated to biocontrol and stress tolerance, providing a basis for future investigation aiming to unravel the complex relationships between genomic endowment and exhibited activities of this strain.

Results

The MLST analysis of ITS-TEF1 concatenated datasets reclassified ITEM 908 as T. atrobrunneum, a species recently described within the T. harzianum species complex and phylogenetically close to T. afroharzianum and T. guizhouense. Genomic analysis revealed the presence of a broad range of genes encoding for carbohydrate active enzymes (CAZYmes), proteins involved in secondary metabolites production, peptaboils, epidithiodioxopiperazines and siderophores potentially involved in parasitism, saprophytic degradation as well as in biocontrol and antagonistic activities. This abundance is comparable to other Trichoderma spp. in the T. harzianum species complex, but broader than in other biocontrol species and in the species T. reesei, known for its industrial application in cellulase production. Comparative analysis also demonstrated similar genomic organization of major secondary metabolites clusters, as in other Trichoderma species.

Conclusions

Reported data provide a contribution to a deeper understanding of the mode of action and identification of activity-specific genetic markers useful for selection and improvement of biocontrol strains. This work will also enlarge the availability of genomic data to perform comparative studies with the aim to correlate phenotypic differences with genetic diversity of Trichoderma species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The fungal genus Trichoderma Pers. comprises numerous species of industrial, biotechnological and agricultural interest [1]. The first comprehensive description of the genus is dated back to 1969 [2] and included nine species-complexes, which grouped morphologically indistinguishable but genetically different species. Recent advancements in Trichoderma taxonomy, supported by the molecular analysis of variable regions of genomic DNA with phylogenetic and taxonomic significance, have led to the current system of more than two-hundred different biological species [3]. Trichoderma spp. have been known to be antagonistic to plant pathogens since the first half of ‘900 [4], but the interest in antagonistic Trichoderma has grown significantly in the last three decades, with the prospect of practical use of these fungi for biological control of plant diseases and as biofertilizers. Intense research on Trichoderma has shown that the beneficial effects of some strains go beyond the direct inhibition of plant pathogens by mycoparasitism, antibiosis and competition and include plant growth promotion [5], solubilization of soil micro- and macro-nutrients [6] and activation of plant systemic resistance [7], in a complex three-way interaction amongst antagonist, pathogen and plant.

In recent years, the availability of genomic sequences of a few Trichoderma species with different mycoparasitic or ecological behaviors has allowed to investigate the genetic bases of biocontrol, the genes involved and the relevant functions, using a comparative approach [8,9,10]. The comparative analyses of Trichoderma genomes have provided new insights and deeper understanding of the biology of Trichoderma species with different lifestyles [8, 11]. Nevertheless, the inference of data provided by genomic analyses with the huge amount of information on Trichoderma biology gained by studies conducted over the past years is difficult. Indeed, most of the biocontrol Trichoderma species and strains used in past studies were not identified according to current criteria, and most of specimens are no longer available for re-examination. Therefore, our knowledge about biocontrol efficacy, mode of action, metabolite production and other biological functions that in were ascribed to one or to another Trichoderma species is jeopardized, and it should be carefully taken and in some cases re-considered. For instance, Chaverri et al. [12] in a revision of the taxonomy of the T. harzianum species complex found that none of the strains in four commercial biocontrol products reported as T. harzianum were actually T. harzianum sensu stricto, but belonged to the new species T. afroharzianum, T. guizhouense and T. simmonsii.

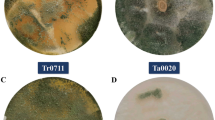

Trichoderma harzianum isolate ITEM 908 is a biocontrol strain which exhibits several interesting biological properties. The isolate was originally selected as a biocontrol agent of damping-off and root and stem rots of tomato and other vegetables caused by Rhizoctonia solani in heavily infested and “tired” soils. Then ITEM 908 was found capable of promoting growth and development of the root system in tomato and to be rhizosphere competent [13]. ITEM 908 was reported to reduce the inoculum of Stemphylium vesicarium and control brown spot of pear after colonization of pear-leaf litter and ground-cover litter in pear orchards [14]. In addition, it was found to antagonize Fusarium graminearum, the causal agent of Fusarium head blight of wheat and other grains, and to inhibit the formation and development of peritecia in vitro [15]. Also, it produces metabolites with fagodeterrent activity that are active against aphid pests [16, 17]. Lately it was found that soil pre-treatment with ITEM 908 determined a decrease in the reproduction rate of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita in tomato plants, thus resulting in reduced severity of nematode attack [18]. Also, ITEM 908 was able to modulate the expression of genes associated with plant immune responses and activate plant defense priming against M. incognita [19]. The isolate ITEM 908 is currently being registered under the European Union regulation as an active ingredient for the production of commercial biopesticides.

We here present the genome sequence of the Trichoderma strain ITEM 908, which we re-classify as T. atrobrunneum F.B. Rocha, P. Chaverri & W. Jaklitsch. Also, we performed an analysis of predicted proteins, focusing on those associated to biocontrol mechanisms and risk assessment, such as carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZYmes), secondary metabolites (SMs), and stress responses. To investigate the relevance of some proteins to the biological functions and lifestyle of ITEM 908, we used a comparative approach [8, 20] based on the annotated gene models of the 20 genome assemblies that were retrievable from the NCBI database at the time we started the analysis (July 2017). The aim of this work was to investigate occurrence and role of some biocontrol-associated genes and provide a basis for future investigations concerned with functions of ITEM 908 and with its interactions.

Results

Properties of T. atrobrunneum genome

The genome of ITEM 908 was sequenced using a whole genome shotgun approach on an Ion S5™ platform (Thermo Fischer Scientific) generating around 7 M reads (Table 1), assembled using the Spades v5.0 software for a total of 804 contigs (705 > 1000 bp), a GC% of 49.18 and a mean coverage of 60×. The overall contiguity of the assembly was good, with a N50 of 129 Kbp; the longest assembled fragment was 552 Kbp in length (performed by QUAST, available at http://quast.sourceforge.net/quast) while the total length of the assembly was of 39,131,654 bp.

This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession PNRQ00000000. The version described in this paper is version PNRQ01000000.

Taxonomic assignment of ITEM 908

The Maximum likelihood (ML) analysis performed with all the ITS-TEF1 concatenated datasets sequences of 100 Trichoderma spp. isolates (Additional file 1) placed ITEM 908 within the T. atrobrunneum group, close to T. afroaharzianum and T. guizhouense (Fig. 1). Therefore, at the state of the art the strain formerly known as T. harzianum ITEM 908 is re-classified as belonging to the species T. atrobrunneum F.B. Rocha, P. Chaverri & W. Jaklitsch, a species recently described within the T. harzianum species complex and phylogenetically close to T. afroharzianum and T. guizhouense [12].

Gene prediction and classification

In the genome of T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908 a total of 8649 genes were predicted (Additional files 2 and 3). Among these, the predicted secretome consisted of 761 proteins, comparable with that of close Trichoderma species [21]. The analysis of the predicted proteome of ITEM 908 using the PFAM annotator software led to the identification of 12,891 functional pfam domains (Additional file 4). GO terms obtained by pfam mapping were classified using CateGOrizer [22]. One thousand seven hundred and eighty-four GO terms were classified into biological process, 1569 into molecular function and 1261 into cellular component. In particular, 757 domains were classified as catalytic activity, 412 under biosynthesis and 233 under hydrolase activity (Fig. 2).

Comparative analysis of pfam domains in Trichoderma spp. genomes

In order to gain insight into the endowment of ITEM 908 with genes putatively associated with biocontrol and stress tolerance, 20 genomes of Trichoderma spp. retrievable in NCBI database were extracted and genes were predicted using the Augustus v3.1 software; the predicted proteomes of these strains and ITEM 908 were then analyzed using the PFAM annotator software. Among all, 15 pfam domains were selected based on their reported involvement in biocontrol-associated functions, such as stress tolerance and parasitic activities. The results of the comparative analysis are summarized in Table 2.

The number of ABC transporters varied within a range of 52 (T. gamsii T6085) and 77 (T. virens IMV 00454), with 60 pfam domains found in ITEM 908 like in T. atroviride IMI 206040, JCM 9410 and XS2015. Considerable variations were found in glutathione transferase (44 to 93 pfam domains) and in the set of peptidases, which ranged from 139 (T. asperellum B05) to 187 (T. virens IMV 00454); 182 peptidase domains were found in ITEM 908 genome. Only two out of four investigated strains of T. virens had the same number (IMI 304061) or more (IMV 00454) peptidases. Also, a comparatively high number of methyltransferase domains were found in ITEM 908. The numbers of HPS70 and kelch motif pfam domains displayed limited variation, ranging from 16 to 20 and from 17 to 20, respectively, with the exception of T. virens IMV 00454 that had 51 pfam for kelch motif. One adenylate cyclase pfam domain was retrieved in all the analyzed Trichoderma spp. The number of hydrophobin pfam domains ranged from 9 (T. parareesei CBS 125925) to 17 (T. hamatum GD12). Forty-one phosphopantetheine attachment site pfam domains were found in the genome of T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908.

CAZYmes

Trichoderma is a model system for the production of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZYmes). This group comprises a list of modules that are classified in the CAZY database (www.cazy.org) as belonging to different families, including glycoside hydrolases (GHs) which catalyze the hydrolysis and/or rearrangement of glycosidic bonds, glycosyl transferases (GTs) that are responsible for the formation of glycosidic bonds, polysaccharide lyases (PLs) which catalyze the non-hydrolytic cleavage of glycosidic bonds, carbohydrate esterases (CEs) which hydrolyze the carbohydrate esters, and auxiliary activities (AAs) which are redox enzymes acting in conjunction with CAZYmes. Due to their important role in parasitism and saprophytic degradation of debris, a focused investigation was performed on the CAZYmes present in the genomes of Trichoderma spp. (Additional file 5: Table S1). In the genome of T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908, 300 domains were retrieved as associated with CAZYmes, including GH family associated domains, starch binding domains and transferases. The number of CAZYme domains in ITEM 908 genome was the second highest among the analyzed Trichoderma species after T. virens IMI 304061 where 344 domains were counted, and equal to T. harzianum B97 MRYK01.1. In ITEM 908 genome we identified 24 pfam domains of the GH18 family, 17 of which with a chitinase active site as predicted by InterPro [23].

The results of the comparative analysis performed by dbCAN (see section Bioinformatic methods) on a restricted number of genomes of Trichoderma spp. are shown in Figs. 3 and 4. The genetic endowment of T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908 with CAZYmes appears to be similar to that of the representatives of the closely related species T. harzianum and significantly higher than T. atroviride IMI206040, T. reesei QM6a and T. virens Gv-29-8 (Fig. 3). T. atrobrunneum and T. harzianum showed the highest number of GH (around 260 each) compared to other Trichoderma species and higher numbers of CE and AA than T. atroviride IMI206040, T. reesei QM6a and T. virens Gv-29-8 (Fig. 3). On the contrary, T. virens harbors the highest endowment of Carbohydrate-Binding Modules. Within the GH class of CAZYmes (http://www.cazy.org) a higher number of members of the GH55 family (exo-β-1,3-glucanase and endo-β-1,3-glucanase) was found in T. atrobrunneum and in T. harzianum, compared to the other analyzed species and isolates (Fig. 4).

As in all ascomycetes filamentous fungi, in ITEM 908 the genes responsible for the conversion of N-acetyl-glucosamine (GlcNAc) to fructose 6-phospate are clustered. The organization of this cluster in ITEM 908 is identical to that reported for T. reesei [24]. The GlcNAc gene cluster (Fig. 5) consists of 5 genes: g4416, coding for a homologue to hxk3; g4417, homologue to the glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase dam1; g4418, homologue to the transcription factor ron1, (regulator of N -acetylglucosamine catabolism), which belongs to a rare family of exclusively fungal transcription factors; g4419, homologue to the GlcNAc-6-phosphate deacetylase dac1; g4420, homologue to β-N-acetylglucosaminidases nag3. We also identified three more genes, two of which (g1686, g2395) are homologous to the GlcNAc:H+symporter ngt1, while the third is an additional transcriptional regulator, homologue of csp2. All these three genes are located outside the cluster as in T. reesei [24].

Secondary metabolites (SMs) genes and gene clusters

Like in other well studied fungal species, also in Trichoderma spp. the genes for secondary metabolism are included in large biosynthetic clusters comprising core enzymes such as polyketide synthases (PKS), non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS), terpene synthase/cyclases, and several additional genes including transcription factor, transporters and oxidoreductases, responsible for the biosynthesis of different secondary metabolites through complex enzymatic pathways.

The genome of T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908 harbors 18 putative PKS, 8 putative NRPS genes, 5 putative PKS-NRPS, and 5 terpene synthase (TS) genes (Additional file 6: Table S2). These numbers are comparable to what reported for other Trichoderma spp., as shown in Table 3.

Polyketides

In the genome of T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908 we identified a genomic locus with similar organization and genic content of the conidial pigment biosynthetic gene cluster described by Atanasova et al. [25] in T. reesei and orthologue of pigment-forming PKSs involved in synthesis of aurofusarin and bikaverin in Fusarium spp. In T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908 the cluster shows the same organization reported for T. virens [26] (Additional file 7: Figure S1). In the PKS cluster we also identified the homologue of the uncharacterized protein with oxidoreductase activity TRIVIDRAFT_90482 (g868), the homologue of the endo-chitosanase TRIVIDRAFT_59043 (g869), the homologue of the Fusarium gip1, the uncharacterized protein with oxidoreductase activity TRIVIDRAFT_69422 (g870). The uncharacterized protein TRIVIDRAFT_153900, homologue of the Fusarium aurZ, was partially predicted as g871, although it misses the initial Met. The gene sequence of the homologue of the pks4, the key gene of the cluster (TRIVIDRAFT_209609, the putative conidial pigment polyketide synthase PksP/Alb1 aurPKS), was identified in this genomic location (NODE_11:113238_119919) and the protein was predicted by the EMBOSS© Sixpack sequence translation tool (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/st/emboss_sixpack/). The homologue of the uncharacterized protein TRIVIDRAFT_49720 was identified as g872, while the homologue of the uncharacterized protein TRIVIDRAFT_192659 was partially predicted as g873.

Non-ribosomal peptides

This class of compounds, which display an extremely broad range of biological activities and pharmacological properties, are mainly represented in Trichoderma by peptaibols, epidithiodioxopiperazines and siderophores. We analyzed the genome sequence of ITEM 908 for the presence of all the Tex NRPSs described for T. virens by Mukherjee et al. [27]. In addition to genes of peptaibol synthetases (tex1, tex2 and tex3), we got evidence of the presence of genomic loci coding for the homologues of tex7 (partially identified as g3551, complete sequence at NODE_16947–36,350), tex8 (NODE_17:22224–5441), tex9 (NODE_142:21235–37,370), tex10 (NODE_7:158284–172,709), tex16 (Node_26:168533–175,690), tex19 (NODE_20:103395–97,482), tex20 (NODE_98:33998–39,293), tex22 (NODE_26_71758–66,286), tex23 (NODE_142:20622–17,120), tex24 (NODE_26:151273–148,142), tex25 (NODE_140:25454–26,758) and tex26 (NODE_26:164315–165,994) [27]. As reported for T. virens, the genes coding for Tex16, Tex24 and Tex26 are located in a putative gene cluster.

Peptaboils

The genome of ITEM 908 harbors three genomic loci with sequences potentially coding for homologues of peptaibol synthetases described in T. virens by Mukherjee et al. [27, 28]. These proteins are characterized by a multimodular architecture [29] and are referred as Tex1 (TRVIDRAFT_66940), Tex2 (TRIVIDRAFT_10003) and Tex3 (TRIVIDRAFT_69362). On the basis of sequence alignment, 3 genomic loci were identified: one for tex1 in the NODE_14:201111–263,835, one for Tex2 in the NODE_29:76842–26,784 and one for Tex3 in the NODE_36:89140–64,378.

Epidithiodioxopiperazines (ETPs)

In Trichoderma, the presence of gene clusters responsible for the biosynthesis of the ETPs sirodesmin (SirP cluster) and gliotoxin (GliP cluster, 12 genes) has been reported [8, 30]. In T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908 we did not find the GliP cluster, similarly to T. atroviride [30], but we identified a genomic locus homologous to the SirP cluster comprised in the NODE_77:109590–134,547. The gene cluster has the same content and organization as the cluster in T. virens [31], with the exception of the aminotransferase sirI and the G-Glutamylcyclotransferase sirG, in which the predicted proteins missed the first 16 and 17 aminoacids, respectively (Fig. 6).

The SirP cluster in T. virens and T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908. The red arrow indicates the non-ribosomal peptide synthetase sirP. Z: zinc finger transcriptional regulator; K: G-Glutamyl cyclotransferase; J: dipeptidase; A: MFS transporter; N: methyltransferase; G: glutathione transferase, C: cytochrome P450 monooxygenase; D: dimethylallyl transferase; I: aminotransferase; T: thioredoxin reductase; N2: methyltransferase

Siderophores

In Trichoderma spp. three NRPSs responsible for siderophore biosynthesis are located in three different gene clusters [10]. The first cluster is responsible for the production of the intracellular ferricrocin. In the genome of ITEM 908 we identified the homologues of the aldehyde dehydrogenase (g626), the oxidoreductase (g625), the NRPS (TRIVIDRAFT_85582 = tex10) (g624), the orntithine monooxygenase (g623) and the transcription factor (g622) (Additional file 8: Figure S2).

The second gene cluster comprise NPS6, a key enzyme which is responsible for extracellular siderophore production in T. virens (ID 44273, [20]) and also found in T. atroviride (ID 39887) and T. reesei (ID 67189). In ITEM 908 the orthologue of this protein was predicted as g4381, with 89% identity with ID 44273 (genomic locus NODE_98:33998–39,283). We also identified the other proteins comprised in the cluster, g4380 orthologue of the AMP-binding protein (96% identity with TRIVIDRAFT_44194), g4379 orthologue of the acyl CoA acyltransferase (94% identity with TRIVIDRAFT_44039), g4378 orthologue of the MFS transporter (90% identity with TRIVIDRAFT_43838), g4377 orthologue of the oxidoreductase (90% identity with TRIVIDRAFT_44141) and g4376, orthologue of the ABC transporter (94% identity with TRIVIDRAFT_210053).

There is an additional genomic locus which comprised a hypothetical cluster with a NRPS siderophore synthase orthologue to the Aspergillus fumigatus sidD gene (or sid4 in Neurospora crassa) (Tr_71005 o Tv_70206 = TRIVIDRAFT_192365). In ITEM 908 we identified a similar locus which contains gene sequences coding for homologues of the NRPS (Tr_71005/ITEM_908_NODE_171:59024–64,759; Tv_70206/ITEM_908_NODE_171:58575–64,402), the ABC transporter, the Acyl-CoA acyltransferase, one hydrolase and one protein with ClpP/crotonase-like domain. While this genomic content is conserved and shared by T. reesei, T. virens and T. atrobrunneum, the gene flanking the NRPS is annotated as an uncharacterized short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases (SDR) family in T. virens (TRIVIDRAFT_51816 fungi.ensamble.org) and as an ABC transporter in T. reesei (sid6 transacylase TRIREDRAFT_82626). In ITEM 908 these gene orthologues are located in two different genomic contents, predicted as NODE_1_length_552646_cov_38.83.g10 (identity of 86%) and as NODE_9_length_343799_cov_42.23.g747 (identity of 83%) respectively [32].

Terpenoids

Trichothecenes are sesquiterpenoid epoxides that are formed starting from the parent compound trichodiene through isomerisation–cyclisation of farnesyl pyrophosphate. This reaction is catalysed by the key enzyme trichodiene synthase, encoded by tri5 gene. Tri5 and other genes of trichothecene biosynthesis are organized in a coordinately regulated gene cluster. In ITEM 908 genome we identified a partial domain similar to tri5 (identity< 30%). The identified gene is not complete, and there is no evidence of the presence of other trichothecene cluster genes in the same genomic location. Similarly, there is no evidence of the presence of the biosynthetic cluster for viridin, a fungistatic and anticancer compound produced by both ‘P’ and ‘Q’ strains of T. virens [33].

Discussion

A comparatively high number of peptidases and methyltransferase domains were found in ITEM 908. Methyltransferases are implicated in regulation of gene expression, and in Trichoderma they have been found to be associated to CAZYmes synthesis and to developmental and trophic functions, such as sporulation and mycoparasitism [34, 35]. In T. reesei, CAZYme encoding genes including those of cellulases, hemicellulases and chitinases, are located in clusters [36], and this organization has also been found in ITEM 908 genome. Marie-Nelly et al. [37] noted that some of the CAZYme clusters in T. reesei were located in the subtelomeric regions, close to the chromosomal ends. In addition, in T. reesei regions containing CAZYme gene clusters were reported to contain also clusters of genes of SM biosynthesis, such as NRPS and PKS, and their distribution is not random, since they are colocalized in discrete regions [36]. This localization is consistent to what reported for SM in other phylogenetically distant fungi [38] and suggest the possibility to rapidly generate genetic diversity which confers an advantage for colonization and antagonistic activity. The co-localization of CAZYme and SM genes in the same regions suggests a possible co-regulation of these genes, confirming the biological importance of CAZYmes clustering. In Aspergillus and Fusarium, clusters of SM genes have been found to be regulated at the level of histones by the enzyme methyltransferase LaeA [39,40,41,42], which also regulates important functions such as conidiation and development, thus affecting the fitness and adaption of the fungus to the environment [43]. LAE1, the orthologue of LaeA, was recently identified in T. atroviride and T. reesei genomes [34, 35], where it is essential for asexual development and mycoparasitism, modulating the production of both CAZYmes and SM. In T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908 the putative orthologue of LAE1 was predicted as g8186, with an identity of 74% and 69% with the proteins identified in T. reesei and T. atroviride respectively. The identity reached 98% with the hypothetical protein THAR02_09616 (GenBank accession KKO98277.1) of T. harzianum strain T6776. The protein was functionally classified as a S-adenosyl-L-methionine-dependent methyltransferase by InterPro [23]. Given the role of the methyltransferase in regulation and co-regulation of CAZYmes and SM biosynthesis, the large number of methyltransferases retrieved in ITEM 908 suggest that also in this strain biocontrol-associated metabolism and biosynthetic activities may be subjected to strong epigenetic regulation. In this regard, further investigations on the role of methyltransferases in regulation and fine tuning of gene expression as for biocontrol- and ecological fitness-associated functions in Trichoderma appear of utmost interest.

Peptidases and proteases catalyze the cleavage of peptide bonds within proteins and are involved in a broad range of biological processes in all organisms. Since fugal cell walls contain lipids and proteins beside chitin and glucan, the involvement of peptidases in mycoparasitism has been hypothesized [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. The basic proteinase-encoding gene prb1 was found in the genome of the plant cell wall degrader T. reesei, as well as in other Trichoderma spp. and, in disagreement with what reported by Herrera-Estrella and coworkers in 1993 [52] based on hybridization techniques, the protein appears to be highly conserved among Trichiderma spp. In T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908 the predicted proteinase g1426 displays 93% of identity with T. atroviride (XP_013940434.1) and T. harzianum (AAA34211.1), 92% with T. virens Gv29–8 (XP_013954377.1), 92% with T. viride (GenBank accession AIZ77170.1) and 91% with T. reesei (XP_006964613.1). The overexpression of prb1 gene in T. harzianum was proven to enhance the biocontrol activity [46] and the presence of this protease in other species may be exploited to improve biocontrol efficacy also in other strains.

Proteases are interesting products of Trichoderma not only because of their possible contribution in fungal cell wall degradation during mycoparasitism, but also for their putative involvement in the interaction with a number of different organisms in different ways. Viterbo and co-workers [53] identified two extracellular aspartyl proteases, namely PapA and PapB, which were induced in T. asperellum during colonization of cucumber roots and were suggested to have a role in establishment of the plant-Trichoderma symbiosis. PapA of T. asperellum had 58% similarity to PapA from T. harzianum, and the encoding gene papA was found to be upregulated by the challenging of Rhizoctonia solani in confrontation tests [53]. In T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908 BLASTP analysis retrieved homologues of proteases encoded by papA and papB with 68% and 85% of identity respectively (g3974 and g1149).

An 18-kD protein from T. virens, which displayed at the amino-terminal a high similarity to a fragment of serine protease from Fusarium sporotrichioides, was identified as an elicitor of plant defense responses [54]. The conserved pfam domain included in this protein is related to the cerato-platanin family containing a number of fungal cerato-platanin phytotoxic proteins approximately 150 residues long. The orthologue of this protein in T. atrobrunneum (g2233) displayed 79% of identity with T. virens although about 30 aa shorter. Furthermore, in T. atrobrunneum genome we counted 5 occurrences of the pfam domain of cerato-platanin in three different proteins.

Proteases also act as proteolytic inactivators of pathogen enzymes and virulence factors [55]. Proteases play also an important role in the mode of action of entomopathogenic [22, 56] and nematophagous [57, 58] microorganisms. Generally speaking, it seems that production of proteinases may play an important role in most pathogen/host interactions. In ascomycetes, plant or insect pathogens were reported to retain peptidases that were mostly lost in saprophytic lineages [22]. In T. harzianum, a trypsin-like acidic serine peptidase encoded by pra1 and the previously cited alkaline serine peptidase PRB1, were reported to have nematicidal activity [49, 59]. Szabó et al. [60] showed that the acidic serine protease pra1, aspartic proteases p6281, the metalloendopeptidase p7455 and the sedolisin serine protease p5216 were co-expressed by T. harzianum during parasitization of eggs of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and suggest a major role of these enzymes in the process. In ITEM 908 we found a PRA1 with 99% identity with PRA1 from T. harzianum.

In ITEM 908, the arsenal of peptidases domains appears to be significantly larger than in most of the species and strains examined. Despite the potential relevance of the proteolytic activity for Trichoderma biocontrol properties, the number of protease genes cloned to date is relatively low compared with those of other biocontrol-associated enzymes. Although in closely related species data on the co-expression of protease encoding genes might imply a common regulatory network, in our strain further studies are needed to determine how many and which genes are associated to the biocontrol capabilities against plant pathogens, insects and nematodes exhibited by this strain.

The glutathione transferases (GSTs, also known as glutathione S-transferase) represent an important group of (mainly) cytosolic enzymes which detoxify both endogenous and exogenous toxic compounds. Relatively little is known about GSTs from fungi and a very limited number of genes have been cloned and sequenced, so far [61]. Dixit and co-workers [62] succeeded in enhancing the Cadmium tolerance of tobacco plants by heterologous expression of a GTS from T. virens. The genetically modified plants showed lower lipid peroxidation and higher levels of antioxidant enzymes, such as GTS, superoxide dismutase, ascorbate peroxidase, guaiacol peroxidase and catalase. In a subsequent work [63], the same research group cloned a GTS encoding gene from T. virens and expressed it in transgenic tobacco plants. Transgenic plants proved to be able to degrade the xenobiotic compound anthracene, while no degradation was observed in wild-type plants. Also, in T. reesei, GTS seem to have a role in degradation of lignocellulosic biomass [64]. A comparatively high number of GTS pfam domains (77) were found in the genome of ITEM 908, which is presumptively indicative of a high number of GTS encoding genes. Enzymes of the GTS family have an outstanding potential for biotechnological applications. They may play a role in various functions associated to biological control and bioremediation, including tolerance to fungicide and agrochemicals, detoxification of toxins produced by competing microorganisms, mitigation of oxidative stress, degradation of recalcitrant polyaromatic pollutants and breakdown of lignocellulosic materials. Also, the possibility exists of heterologous expression of these enzymes in transgenic plants to enhance tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses. The investigation of catalytic and structural diversity of GSTs of ITEM 908 may open interesting prospects of successful applications in the above fields of research and biotechnology.

ABC transporters are transmembrane proteins that have the ability to transport molecules, such as toxins, ions and proteins into and out of cells by an energy-consuming process involving ATP hydrolysis. They are known to contribute to resistance against toxic compounds in microbial pathogens and tumor cells. In Trichoderma, ABC transporters are thought be involved in extrusion of endogenous metabolites and protection from exogenous toxicants, such as plant phytoalexins, microbial toxins and pesticides [65]. Schmoll et al. [9] found a strong expansion in the number of ABC transporters in T. virens, T. atroviride, and T. reesei compared to N. crassa, S. cerevisiae, or S. pombe and suggested that this reflects the adaption to their ecological niches and lifestyles, i.e., mycoparasitism competition with other soil organisms and plant litter decomposer. We identified 60 ABC transporters in ITEM 908 and 52 to 77 in the others 20 isolates examined, which is consistent with the findings of Schmoll et al. [9].

CAZYmes in Trichoderma spp. play a central role in both mycoparasitism and degradation of plant residues. For this reason, they are regarded as indicators of bio- or necrotrophic parasitic lifestyle, and of saprophytic capability of colonizing plant litter [8, 9]. The main constituents of the fungal cell wall are chitin and glucan. Conversely, in plant cell wall the major carbohydrates are cellulose, hemicelluloses and pectins. According to Schmoll et al. [9], the ecological behavior of the mycoparasites T. atroviride and T. virens, compared to the plant wall degrader T. reesei, is reflected by the sizes of the respective genomes. The smaller size of T. reesei genome (34.1 Mbp versus 36.1 and 38.8 Mbp of T. atroviride and T. virens) is conceivably due to the loss of gene functional to mycoparasitism during the evolution of T. reesei [8]. In the genome of ITEM 908 (39.2 Mbp) we found the highest number of CAZYme domains among the species and the strains analyzed except for T. virens IMI 304061, with a significantly higher relative abundance of enzymes in the GH (glycoside hydrolases), CE (carbohydrate esterases) and AA (auxiliary activity) families and a smaller proportion of non-catalytic carbohydrate-binding modules (CBM). Among the carbohydrate hydrolases, the family GH18, containing enzymes involved in chitin degradation, is strongly represented in Trichoderma, particularly in T. atroviride and T. virens that have been reported to contain the highest number of chitinolytic enzymes of all described fungi [8]. Since chitin is the main component of fungal cell walls, secretion of chitinolytic enzymes is essential for mycoparasitization and also part of the combined synergistic action with peptaibol antibiotics that leads to prey death [66]. In T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908 genome we identified 24 domains of the GH18 family, comparable to the other species in the T. harzianum species complex T. guizhouense and T. harzianum. Glucanases are inductively produced by mycoparasitic Trichoderma species grown on media containing chitin or fungal cell walls as the sole carbon source [67, 68] and also have been reported to be induced during mycoparasitism [69]. Comparative genome analysis revealed that the mycoparasites have more glucanases than T. reesei [9]. Consistently with the findings of Schmoll et al. [9], the number of cellulases and xylanases found in ITEM 908 was not significantly higher than in other Trichoderma spp. genomes, supporting their conclusion that a low variation in cellulases and xylanases is a common feature of the genus Trichoderma.

Despite the high number of PKS genes identified in Trichoderma spp., the related biosynthetic pathways are not yet characterized. In fungi, PKS are often associated with synthesis of pigments. In T. reesei Atanasova et al. [25] identified the gene pks4 as an orthologue of pigment-forming PKS involved in synthesis of aurofusarin and bikaverin in Fusarium spp. Deletion of the key gene pks4 affected conidia pigmentation and cell wall stability, secondary metabolites production and antagonistic activity of T. reesei [25]. Recently, two PKS genes, pksT-1 and pksT-2, were isolated from T. harzianum and found to be differentially expressed during challenge with the plant pathogenic fungi Rhizoctonia solani, S. sclerotiorum and F. oxysporum [70]. We identified a gene similar to pks4 in the genome of T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908, but its relevance for biocontrol ability and physiology of ITEM 908 remains to be ascertained.

The analysis made by Mukherjee et al. [27] on the genome of T. virens Gv29–8 is so far the most extensive study on the occurrence and role of NPKS and hybrid NRPS/PKS in Trichoderma. Based on similarity of sequences and knock-down experiments, the authors predicted putative functions for some of the 22 NPKSs (Tex1–10 and 15–26) and four hybrid NRPS/PKS (Tex11–14) identified. In ITEM 908 we found homologues of Tex1–3 (peptaibol synthetase), Tex10 (ferrichrome synthetase), Tex20 (siderophore synthetases) and Tex19 (sirodesmin synthetase). We also found orthologues of the genes tex2, tex7–8, and tex25 that in T. virens were upregulated in the presence of maize roots [27] and that are therefore conceivably involved in the plant-fungus interaction, although in ways that are still unknown.

Peptaibols are linear or, in few instances, cyclic peptides made of 4–21 residues and characterized by the presence of the nonproteinogenic amino acid α-aminoisobutyric acid and, in some cases, of isovaline. Peptaibols have plasma membrane-permeabilizing properties and have been associated to important biological functions in Trichoderma, such as mycoparasitism, for which they operate synergistically with secreted hydrolytic enzymes [71] and elicitation of plant defense response [72]. Production of peptaibols is widely diffused in species of Trichoderma [73] that can synthesize a number of different forms, often showing microheterogeneity [74]. This is due to the ability of single peptaibol synthetases to produce a variety of peptaibols by a module skipping mechanism [27, 75]. So far three genes of paptaibol synthetases, named tex1, tex2 and tex3 have been identified in T. virens genome. Tex1 is a long-chain peptide (18–25 residues) peptaibol synthetase, and it is involved in the production of 18-residue peptaibols [29]. The 18-residues product of Tex1 was proven to be an elicitor of systemic resistance [72]. Later, the short peptaibol synthetase gene tex2, encoding a 14-module enzyme able to assemble both 11-residue and 14-residue peptaibols, was characterized [28]. The third peptaibol synthetase gene (tex3), homologous to tex1 has seven complete modules arranged in a linear fashion [27]. We found homologues of all of these three genes in the genome of T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908.

ETPs are molecules with toxic activity conferred by the capability to generate reactive oxygen species by cross-linking proteins via the ETPs disulphide bridge [76]. The ETP gliotoxin has antifungal activity and so far, it has been found only in “Q” strains of the species T. virens and its role in antagonism to Rhizoctonia has been recognized. Gliotoxin is absent in “P” strains of T. virens that instead produce the ETP gliovirin, which has potent antimicrobial properties particularly against Pythium and other oomycetes. The production of ETPs is discontinuous in the fungal kingdom. The gene clusters responsible for the production of the ETPs sirodesmin (SirP cluster) and gliotoxin (GliP cluster, 12 genes), were first characterized in the ascomycetes Leptosphaeria maculans and the human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus [77, 78], respectively, but then identified also in Trichoderma spp. [8, 30]. SirP and GliP clusters of A. fumigatus and L. maculans are 55 and 28 kb in length, respectively and share ten genes. The GliP cluster present in T. virens genome consists of 8 genes only, but its association with gliotoxin biosynthesis has been proven [79]. A GliP cluster is present in T. reesei, even though this species does not produce gliotoxin [30]. Trichoderma virens also has a gene cluster similar to SirP, encoding a so far unidentified secondary metabolite [30]. However, since none of the SirP gene cluster members has been found to be expressed in Trichoderma during mycoparasitism (C. P. Kubicek, unpublished results cited in [30]), the cluster might be not functional, or the metabolite might be not required for antagonism. In T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908 we identified only a genomic locus homologue to the SirP cluster and did not find the GliP cluster. Since gliotoxin has potential non-target toxic effects [76], the absence of GliP cluster and the resulting inability to produce gliotoxin is of importance for risk assessment and authorization of ITEM 908-based plant protection products.

Siderophores are small metal-chelating molecules produced by several microorganisms under low iron conditions to chelate the ferric iron [Fe(III)] from the surrounding environment. They also form complexes with other essential micro elements and make them available to the plant [80]. Siderophores play a role in biocontrol of plant diseases by causing Fe starvation of phytopathogens, thus fostering successful competition by biocontrol agents [81]. Also, microbial siderophores play a major role in fertility of soils, plant health and plant nutrition [82]. Fungal siderophores are comprised in three main groups: fusarinines, coprogens and ferrichromes, all belonging to the hydroxamate-class [83]. On average, Trichoderma spp. are able to produce 12–14 siderophores [84]. Trichoderma siderophores are regarded as part of the mechanism of biocontrol [85] and plant growth promotion [86]. As reviewed by Zeilinger et al. [10], in Trichoderma spp. the NRPSs responsible for siderophore biosynthesis are located in three different gene clusters. Accordingly, in ITEM 908 genome we found three NRPS homologues of the NRPS responsible for the synthesis of ferricrocin, of NPS6 involved in synthesis of extracellular siderophores, and of the siderophore synthase sidD, which were arranged in three distinct clusters. Ferricrocin is responsible for intracellular storage of iron and is involved in protection of cells from oxidative stress [87]. The extracellular siderophore produced by NPS6 also contributes to protection of the fungus from oxidative stress [88]. Previous studies on NRPSs involved in siderophore biosynthesis in Trichoderma reported that the genomes of T. reesei, T. virens and T. atroviride all have a single gene for ferricrocin synthesis; genes orthologues of NPS6 and SidD are in the genomes of T. reesei and T virens, while T. atroviride harbors only the NPS6 orthologue [8, 30].

Trichothecenes represent a large family of terpenoid mycotoxins produced by a variety of filamentous fungi, and most notably by species belonging to the genera Fusarium, Myrothecium and Stachybotrys [89]. The trichothecenes trichodermin, its deacetyl derivative trichodermol and harzianum A have been identified in cultures of Trichoderma spp. [90]. The tri5 gene encoding for trichodiene synthase, the key enzyme of trichothecene biosynthesis was first characterized in Trichoderma by Gallo et al. [91]. Unlike in Fusarium, in Trichoderma this gene is located outside the trichothecenes biosynthetic cluster (TRI) [92]. So far, the only well-characterized Trichoderma strains that were reported to harbor orthologues genes of the Fusarium TRI cluster belong to the species T. arundinaceum and T. brevicompactum [92]. Similarly to gliotoxin, the ability to produce trichothecenes can be a safety issue as for registration of Trichoderma-based biopesticides. In this regard, the genome of T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908 does not harbor either the TRI gene cluster or the tri5 gene and this rules out the risk of occurrence of trichothecenes in formulations and treated plants.

Conclusions

For decades biocontrol strains of Trichoderma have been selected through in vitro confrontation tests followed by extensive trials in the greenhouse and the field. This trial and error procedure, besides being time and labor consuming, has often led to misleading conclusions and unreliable biocontrol. A drastic change of prospect has come with science-based improvement of biocontrol performances based on understanding of the mechanisms of action and the complex plant-pathogen-biocontrol agent interactions. Molecular techniques have allowed more in-depth studies on this subject, but the interpretation of the results has been in some extent limited by the lack of genome sequence information for biocontrol Trichoderma species or strains [93]. In this regard, the presentation of the genome of the multi-target biocontrol strain ITEM 908, belonging to the newly constituted species T. atrobrunneum, is a contribution to the understanding of the mode of action and the identification of activity-specific genetic markers that can be used for selection and improvement of biocontrol strains. It extends the number of genomes available for comparative studies aiming to correlate phenotypic differences with genetic diversity of Trichoderma species. In conclusion, this work provides a basis to further “omics” studies for a deeper understanding of the complex interactions of this strain with its multiple targets and with plants, and for the development of a knowledge-driven selection of effective Trichoderma biocontrol strains.

Methods

Genome sequencing and assembly

The antagonistic strain T. atrobrunneum (formerly T. harzianum) ITEM 908 was originally isolated from soil collected in Apulia, Italy, and maintained in the Agri-Food Toxigenic Fungi Culture Collection of the Institute of Sciences of Food Production, CNR, Bari (http://www.ispa.cnr.it/Collection). A monoconidial culture was grown for 5 days on PDA (Potato Dextrose agar, Oxoid, Italy). Fungal mycelium was then scraped off the agar surface and ground in a mortar using liquid nitrogen to a fine powder. DNA extraction was performed from 10 mg of lyophilized material using the “Wizard ® Magnetic DNA purification system for Food” (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quantity and quality of isolated DNA was determined a NanoDrop-2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) and a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies). DNA was then subjected to whole genome shotgun sequencing using the Ion S5™ library preparation workflow (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltman, MA, USA). Four hundred bp mate-paired reads were generated on the Ion S5™ System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Duplicate reads were removed by FilterDuplicates (v5.0.0.0) Ionplugin. De novo assembly was performed by AssemblerSpades (v.5.0) Ionplugin™.

Phylogenetic analysis

Species assignment of ITEM 908 was achieved by application of the genealogical concordance phylogenetic species recognition concept based on the gene sequences of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and translation elongation factor 1-α (TEF1), recognized as the most informative for species discrimination in Trichoderma [12]. Genomic sequence of ITS and TEF1 were extracted from ITEM 908 assembly, using the corresponding loci sequences of T. harzianum strain T22 (NCBI Accession n. KX632495.1 and KX632609.1) as query. To construct the phylogenetic tree, we used the ITS/TEF1 concatenated datasets of a total of 100 ITS1-IT2 and TEF1 Trichoderma spp. sequences retrieved by GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/). Molecular phylogenetic analysis was performed by Maximum Likelihood (ML) method. Consensus tree was inferred using the neighbour-joining method using MEGA v7.0.18 (http://www.megasoftware.net/). Phylogenetic robustness was inferred from 1000 replications to obtain the confidence value for the aligned sequence dataset.

Bioinformatic methods

Genes were predicted using the Augustus v3.1 software implemented in the Galaxy platform [94] with a model trained on T. reesei [32] (gene annotation and mapping available at http://trichocode.com/index.php/t-reesei). The predicted proteins were submitted to the PFAM annotator tool within the Galaxy platform (Galaxy Tool Version 1.0.0) in order to predict the pfam domains.

To analyze the Gene Ontology (GO) terms for all the pfam domains predicted we mapped them against the list generated from data supplied by InterPro for the InterPro2GO mapping [95, 96]. The web-based program Categorizer [97] was used to analyze and classify the GO terms for all the identified domains.

The secretome of T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908 was in silico predicted by SignalP [98] (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/). This software predicts the presence of signal peptide cleavage sites at the N-terminus in amino acid sequences of a protein, which are used to move it into the endoplasmic reticulum and for secretion.

To perform the comparative analysis of selected pfam domain we retrieved the genomes of 20 Trichoderma strains available in GenBank (Additional file 9: Table S3). For each genome genes were predicted using Augustus v3.1 software and pfam domains annotated using the PFAM annotator tool implemented in the Galaxy platform. Fifteen pfam domains (Table 2) were selected based on their involvement in stress tolerance and antagonistic activities.

The CAZYmes annotation was performed by dbCAN (release 6.0, available at http://csbl.bmb.uga.edu/dbCAN/; [99]), web server and DataBase for automated Carbohydrate-active enzyme Annotation.

For the analysis of secondary metabolites genes and gene clusters, enzyme sequences were downloaded from the genome site of T. virens Gv29–8 (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/TriviGv29_8_2/ TriviGv29_8_2.home.html), T. atroviride (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Triat2/Triat2.home.html) and T. reesei (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Trire2/ Trire2.home.html). The homology-based relationship of T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908 predicted proteins towards selected proteins was determined by BLASTP algorithm on the NCBI site (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Gene models were determined manually, and clustering and orientation were subsequently deduced for the closely linked genes.

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

Auxiliary activity

- ALDH:

-

Aldehyde dehydrogenase

- CAZYmes:

-

Carbohydrate active enzymes

- CBM:

-

Non-catalytic carbohydrate-binding modules

- CE:

-

Carbohydrate esterase

- ETP:

-

Epidithiodioxopiperazines

- GH:

-

Glycoside hydrolase

- GlcNAc:

-

N-acetyl-glucosamine

- GO:

-

Gene Ontology

- GST:

-

Glutathione transferase

- GT:

-

Glycosyl transferase

- ITS:

-

Internal transcribed spacer

- ML:

-

Maximum likelihood

- NRPS:

-

Non-ribosomal peptide synthetase

- OMO:

-

Ornithine monooxygenase

- OXD:

-

Oxidoreductase

- PK:

-

Polyketide synthase

- PL:

-

Polysaccharide lyase

- SDR:

-

Short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases

- SM:

-

Secondary metabolite

- TEF1:

-

Translation elongation factor 1-α

- TF:

-

Transcription factor

- TRI:

-

Trichothecenes biosynthetic cluster

- TS:

-

Terpene synthase

References

Harman GE, Kubicek CP. Trichoderma and Gliocladium. 2. Enzymes, biological control and commercial applications. London: Taylor & Francis; 1998. xiv + 393 p.

Rifai MA. A revision of the genus Trichoderma. Mycol Papers. 1969;116:1–56.

Bissett J, Gams W, Jaklitsch W, Samuels GJ. Accepted Trichoderma names in the year 2015. IMA Fungus. 2015;6(2):263–95.

Weindling R. Trichoderma lignorum as a parasite of other soil fungi. Phytopathology. 1932;22:837–45.

López-Bucio J, Pelagio-Flores R, Herrera-Estrella A. Trichoderma as biostimulant: exploiting the multilevel properties of a plant beneficial fungus. Sci Hortic. 2015;196:109–23.

Altomare C, Norvell WA, Björkman T, Harman GE. Solubilization of phosphates and micronutrients by the plant-growth promoting and biocontrol fungus Trichoderma harzianum Rifai 1295-22. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65(7):2926–33.

Shoresh M, Harman GE, Mastouri F. Induced systemic resistance and plant responses to fungal biocontrol agents. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2010;48:21–43.

Kubicek CP, Herrera-Estrella A, Seidl-Seiboth V, Martinez DA, Druzhinina IS, Thon M, Zeilinger S, Casas-Flores S, Horwitz BA, Mukherjee PK, Mukherjee M, Kredics L, Alcaraz LD, Aerts A, Antal Z, Atanasova L, Cervantes-Badillo MG, Challacombe J, Chertkov O, McCluskey K, Coulpier F, Deshpande N, von Dohren H, Ebbole DJ, Esquivel-Naranjo EU, Fekete E, Flipphi M, Glaser F, Gomez-Rodriguez EY, Gruber S, Han C, Henrissat B, Hermosa R, Hernandez-Onate M, Karaffa L, Kosti I, Le Crom S, Lindquist E, Lucas S, Lubeck M, Lubeck PS, Margeot A, Metz B, Misra M, Nevalainen H, Omann M, Packer N, Perrone G, Uresti-Rivera EE, Salamov A, Schmoll M, Seiboth B, Shapiro H, Sukno S, Tamayo-Ramos JA, Tisch D, Wiest A, Wilkinson HH, Zhang M, Coutinho PM, Kenerley CM, Monte E, Baker SE, Grigoriev IV. Comparative genome sequence analysis underscores mycoparasitism as the ancestral life style of Trichoderma. Genome Biol. 2011;12(4):R40.

Schmoll M, Dattenböck C, Carreras-Villaseñor N, Mendoza-Mendoza A, Tisch D, Alemán MI, Baker SE, Brown C, Cervantes-Badillo MG, Cetz-Chel J, Cristobal-Mondragon GR, Delaye L, Esquivel-Naranjo EU, Frischmann A, Gallardo-Negrete Jde J, García-Esquivel M, Gomez-Rodriguez EY, Greenwood DR, Hernández-Oñate M, Kruszewska JS, Lawry R, Mora-Montes HM, Muñoz-Centeno T, Nieto-Jacobo MF, Nogueira Lopez G, Olmedo-Monfil V, Osorio-Concepcion M, Piłsyk S, Pomraning KR, Rodriguez-Iglesias A, Rosales-Saavedra MT, Sánchez-Arreguín JA, Seidl-Seiboth V, Stewart A, Uresti-Rivera EE, Wang CL, Wang TF, Zeilinger S, Casas-Flores S, Herrera-Estrella A. The genomes of three uneven siblings: footprints of the lifestyles of three Trichoderma species. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2016;80(1):205–327.

Zeilinger S, Gruber S, Bansal R, Mukherjee PK. Secondary metabolism in Trichoderma - chemistry meets genomics. Fungal Biol Rev. 2016;30:74–90.

Druzhinina IS, Seidl-Seiboth V, Herrera-Estrella A, Horwitz BA, Kenerley CM, Monte E, Mukherjee PK, Zeilinger S, Grigoriev IV, Kubicek CP. Trichoderma: the genomics of opportunistic success. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9(10):749–59.

Chaverri P, Branco-Rocha F, Jaklitsch W, Gazis R, Degenkolb T, Samuels GJ. Systematics of the Trichoderma harzianum species complex and the re-identification of commercial biocontrol strains. Mycologia. 2015;107:558–90.

Marzano M, Gallo A, Altomare C. Improvement of biocontrol efficacy of Trichoderma harzianum vs. Fusarium oxysporum f. Sp. lycopersici through UV-induced tolerance to fusaric acid. Biol Control. 2013;67:397–408.

Rossi V, Pattori E. Inoculum reduction of Stemphylium vesicarium, the causal agent of brown spot of pear, through application of Trichoderma-based products. Biol Control. 2009;49:52–7.

Altomare C, Branà MT, Gallo A, Cozzi G, Logrieco AF. Inhibition of formation of perithecia of Fusarium graminearum by antagonistic isolates of Trichoderma spp. In: De Saeger, S.; Logrieco, A. Report from the 1st MYCOKEY International Conference Global Mycotoxin Reduction in the Food and Feed Chain Held in Ghent, Belgium, 11–14 September 2017. Toxins. 2017;9:276. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins9090276.

Ganassi S, De Cristofaro A, Grazioso P, Altomare C, Logrieco A, Sabatini MA. Detection of fungal metabolites of various Trichoderma species by the aphid Schizaphis graminum. Entomol Exp Appl. 2007;122:77–86.

Ganassi S, Grazioso P, De Cristofaro A, Fiorentini F, Sabatini MA, Evidente A, Altomare C. Long chain alcohols produced by Trichoderma citrinoviride have phagodeterrent activity against the bird cherry-oat aphid Rhopalosiphum padi. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:297.

Leonetti P, Costanza A, Zonno MC, Molinari S, Altomare C. Potential of Trichoderma harzianum for biological control of Meloidogyne incognita, the root-knot nematode of tomato. IOBC-WPRS Bulletin. 2016;115:143–50.

Leonetti P, Zonno MC, Molinari S, Altomare C. Induction of SA-signaling pathway and ethylene biosynthesis in Trichoderma harzianum-treated tomato plants after infection of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Plant Cell Rep. 2017;6(4):621–31.

Mukherjee PK, Horwitz BA, Herrera-Estrella A, Schmoll M, Kenerley CM. Trichoderma research in the genome era. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2013;51:105–29.

Druzhinina IS, Shelest E, Kubicek CP. Novel traits of Trichoderma predicted through the analysis of its secretome. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2012;337(1):1–9.

Hu G, St. Leger J. A phylogenomic approach to reconstructing the diversification of serine proteases in fungi. J Evol Biol. 2004;17:1204–14.

Finn RD, Attwood TK, Babbitt PC, Bateman A, Bork P, Bridge AJ, Chang HY, Dosztányi Z, El-Gebali S, Fraser M, Gough J, Haft D, Holliday GL, Huang H, Huang X, Letunic I, Lopez R, Lu S, Marchler-Bauer A, Mi H, Mistry J, Natale DA, Necci M, Nuca G, Orengo CA, Park Y, Pesseat S, Piovesan D, Potter SC, Rawlings ND, Redaschi N, Richardson L, Rivoire C, Sangrador-Vegas A, Sigrist C, Sillitoe I, Smithers B, Squizzato S, Sutton G, Thanki N, Thomas PD, Tosatto SC, Wu CH, Xenarios I, Yeh LS, Young SY, Mitchell AL. InterPro in 2017 - beyond protein family and domain annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D190–9.

Kappel L, Gaderer R, Flipphi M, Seidl-Seiboth V. The N-acetylglucosamine catabolic gene cluster in Trichoderma reesei is controlled by the Ndt80-like transcription factor RON1. Mol Microbiol. 2016;99(4):640–57.

Atanasova L, Knox BP, Kubicek CP, Druzhinina IS, Baker SE. The polyketide synthase gene pks4 of Trichoderma reesei provides pigmentation and stress resistance. Eukaryot Cell. 2013;12:1499–508.

Baker SE, Perrone G, Richardson NM, Gallo A, Kubicek CP. Phylogenomic analysis of polyketide synthase-encoding genes in Trichoderma. Microbiology. 2012;158:147–54.

Mukherjee PK, Buensanteai N, Moran-Diez ME, Druzhinina IS, Kenerley CM. Functional analysis of non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) in Trichoderma virens reveals a polyketide synthase (PKS)/NRPS hybrid enzyme involved in the induced systemic resistance response in maize. Microbiology. 2012;158:155–65.

Mukherjee PK, Wiest A, Ruiz N, Keightley A, Moran-Diez ME, McCluskey K, Pouchus YF, Kenerley CM. Two classes of new peptaibols are synthesized by a single non-ribosomal peptide synthetase of Trichoderma virens. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(6):4544–54.

Wiest A, Grzegorski D, Xu BW, Goulard C, Rebuffat S, Ebbole DJ, Bodo B, Kenerley C. Identification of Peptaibols from Trichoderma virens and cloning of a Peptaibol Synthetase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20862–8.

Mukherjee PK, Horwitz BA, Kenerley CM. Secondary metabolism in Trichoderma - a genomic perspective. Microbiology. 2012;158:35–45.

Patron NJ, Waller RF, Cozijnsen AJ, Straney DC, Gardiner DM, Nierman WC, Howlett BJ. Origin and distribution of epipolythiodioxopiperazine (ETP) gene clusters in filamentous ascomycetes. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:174.

Druzhinina IS, Kopchinskiy AG, Kubicek EM, Kubicek CP. A complete annotation of the chromosomes of the cellulase producer Trichoderma reesei provides insights in gene clusters, their expression and reveals genes required for fitness. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2016;9:75.

Howell CR, Stipanovic RD, Lumsden RD. Antibiotic production by strains of Gliocladium virens and its relation to the bio-control of cotton seedling diseases. Biocontrol Sci Tech. 1993;3:435–41.

Seiboth B, Karimi RA, Phatale PA, Linke R, Hartl L, Sauer DG, Smith KM, Baker SE, Freitag M, Kubicek CP. The putative protein methyltransferase LAE1 controls cellulase gene expression in Trichoderma reesei. Mol Microbiol. 2012;84(6):1150–64.

Aghcheh RK, Druzhinina IS, Kubicek CP. The putative protein methyltransferase LAE1 of Trichoderma atroviride is a key regulator of asexual development and mycoparasitism. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67144.

Martinez D, Berka RM, Henrissat B, Saloheimo M, Arvas M, Baker SE, Chapman J, Chertkov O, Coutinho PM, Cullen D, Danchin EG, Grigoriev IV, Harris P, Jackson M, Kubicek CP, Han CS, Ho I, Larrondo LF, de Leon AL, Magnuson JK, Merino S, Misra M, Nelson B, Putnam N, Robbertse B, Salamov AA, Schmoll M, Terry A, Thayer N, Westerholm-Parvinen A, Schoch CL, Yao J, Barabote R, Nelson MA, Detter C, Bruce D, Kuske CR, Xie G, Richardson P, Rokhsar DS, Lucas SM, Rubin EM, Dunn-Coleman N, Ward M, Brettin TS. Genome sequencing and analysis of the biomass-degrading fungus Trichoderma reesei (syn. Hypocrea jecorina). Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(5):553–60.

Marie-Nelly H, Marbouty M, Cournac A, Flot J-F, Liti G, Poggi Parodi D, Syan S, Guillén N, Margeot A, Zimmer C, Koszul R. High-quality genome (re)assembly using chromosomal contact data. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5695.

Chiara M, Fanelli F, Mulè G, Logrieco AF, Pesole G, Leslie JF, Horner D, Toomajian C. Genome sequencing of multiple isolates highlights subtelomeric genomic diversity within Fusarium fujikuroi. Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7(11):3062–9.

Bok JW, Keller NP. LaeA, a regulator of secondary metabolism in Aspergillus spp. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:527–35.

Bok JW, Chiang YM, Szewczyk E, Reyes-Dominguez Y, Davidson AD, Sanchez JF, Lo HC, Watanabe K, Strauss J, Oakley BR, Wang CC, Keller NP. Chromatin-level regulation of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:462–4.

Bayram O, Braus GH. Coordination of secondary metabolism and development in fungi: the velvet family of regulatry proteins. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36:1–24.

Butchko RA, Brown DW, Busman M, Tudzynski B, Wiemann P. Lae1 regulates expression of multiple secondary metabolite gene clusters in Fusarium verticillioides. Fungal Genet Biol. 2012;49:602–12.

Reyes-Dominguez Y, Bok JW, Berger H, Shwab EK, Basheer A, Gallmetzer A, Scazzocchio C, Keller N, Strauss J. Heterochromatic marks are associated with the repression of secondary metabolism clusters in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Microbiol. 2010;76(6):1376–86.

Geremia RA, Goldman GH, Jacobs D, Ardiles W, Vila SB, Van Montagu M, Herrera-Estrella A. Molecular characterization of the proteinase-encoding gene, prb1, related to mycoparasitism by Trichoderma harzianum. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8(3):603–13.

Suárez MB, Sanz L, Chamorro MI, Rey M, González FJ, Llobell A, Monte E. Proteomic analysis of secreted proteins from Trichoderma harzianum Identification of a fungal cell wall-induced aspartic protease. Fungal Genet Biol. 2005;42:924–34.

Flores A, Chet I, Herrera-Estrella A. Improved biocontrol activity of Trichoderma harzianum by over-expression of the proteinase-encoding gene prb1. Curr Genet. 1997;31(1):30–7.

Olmedo-Monfil V, Mendoza-Mendoza A, Gómez I, Cortés C, Herrera-Estrella A. Multiple environmental signals determine the transcriptional activation of the mycoparasitism related gene prb1 in Trichoderma atroviride. Mol Genet Genomics. 2002;267:703–12.

Pozo MJ, García JM, Kenerley CM. Functional analysis of tvsp1, a serine protease-encoding gene in the biocontrol agent Trichoderma virens. Fungal Genet Biol. 2004;41(3):336–48.

Suarez B, Rey M, Castillo P, Monte E, Llobell A. Isolation and characterization of PRA1, a trypsin-like protease from the biocontrol agent Trichoderma harzianum CECT 2413 displaying nematicidal activity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;65:46–55.

Liu Y, Yang Q. Cloning and heterologous expression of aspartic protease SA76 related to biocontrol in Trichoderma harzianum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;277:173–81.

Liu Y, Yang Q. Cloning and heterologous expression of SS10, a subtilisin-like protease displaying antifungal activity from Trichoderma harzianum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;290:54–61.

Herrera-Estrella A, Goldman GH, Van Montagu M, Geremia RA. Electrophoretic karyotype and gene assignment to resolved chromosomes of Trichoderma spp. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7(4):515–21.

Viterbo A, Harel M, Chet I. Isolation of two aspartyl proteases from Trichoderma asperellum expressed during colonization of cucumber roots. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;238:151–8.

Hanson LE, Howell CR. Elicitors of plant defense responses from biocontrol strains of Trichoderma virens. Phytopathology. 2004;94:171–6.

Elad Y, Kapat A. The role of Trichoderma harzianum protease in the biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea. Eur J Plant Pathol. 1999;105:177–89.

de Carolina Sánchez-Pérez L, Barranco-Florido JE, Rodríguez-Navarro S, Cervantes-Mayagoitia JF, Ramos-López MÁ. Enzymes of entomopathogenic fungi, advances and insights. Adv Enzyme Res. 2014;2:65–76.

Tunlid A, Jansson S. Proteases and their involvement in the infection and immobilization of nematodes by the nematophagous fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:2868–72.

Geng C, Nie X, Tang Z, Zhang Y, Lin J, Sun M, Peng D. A novel serine protease, Sep1, from Bacillus firmus DS-1 has nematicidal activity and degrades multiple intestinal-associated nematode proteins. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25012.

Sharon E, Bar-Eyal M, Chet I, Herrera-Estrella A, Kleifeld O, Spiegel Y. Biological control of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica by Trichoderma harzianum. Phytopathology. 2001;91(7):687–93.

Szabò M, Urban P, Virányia F, Kredicsc L, Fekete C. Comparative gene expression profiles of Trichoderma harzianum proteases during in vitro nematode egg-parasitism. Biol Control. 2013;67:337–43.

Sheehan D, Meade G, Foley VM, Dowd CA. Structure, function and evolution of glutathione transferases: implications for classification of non-mammalian members of an ancient enzyme superfamily. Biochem J. 2001;360(1):16.

Dixit P, Mukherjee PK, Ramachandran V, Eapen S. Glutathione transferase from Trichoderma virens enhances cadmium tolerance without enhancing its accumulation in transgenic Nicotiana tabacum. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):1–15.

Dixit P, Mukherjee PK, Sherkhane PD, Kale SP, Eapen S. Enhanced tolerance and remediation of anthracene by transgenic tobacco plants expressing a fungal glutathione transferase gene. Hazard Mater. 2011;192(1):270–6.

Adav SS, Chao LT, Sze SK. Quantitative secretomic analysis of Trichoderma reesei strains reveals enzymatic composition for lignocellulosic biomass degradation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11(7):1–15.

Ruocco M, Lanzuise S, Vinale F, Marra R, Turrà D, Woo SL, Lorito M. Identification of a new biocontrol gene in Trichoderma atroviride: the role of an ABC transporter membrane pump in the interaction with different plant-pathogenic fungi. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2009;22(3):291–301.

Harman GE, Howell CR, Viterbo A, Chet I, Lorito M. Trichoderma species-opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2(1):43–56.

de la Cruz J, Pintor-Toro JA, Benítez T, Llobell A. Purification and characterization of an endo-β-1,6-glucanase from Trichoderma harzianum that is related to its mycoparasitism. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1864–71.

da Silva Aires R, Steindorff AS, Soller Ramada MH, Linhares de Siqueira SJ, Ulhoa CJ. Biochemical characterization of a 27 kDa 1,3-β-d-glucanase from Trichoderma asperellum induced by cell wall of Rhizoctonia solani. Carbohydr Polym. 2012;87:1219–23.

Marcello CM, Steindorff AS, da Silva SP, Silva Rdo N, Mendes Bataus LA, Ulhoa CJ. Expression analysis of the exo-beta-1,3-glucanase from the mycoparasitic fungus Trichoderma asperellum. Microbiol Res. 2010;165(1):75–81.

Yao L, Tan C, Song J, Yang Q, Yu L, Li X. Isolation and expression of two polyketide synthase genes from Trichoderma harzianum 88 during mycoparasitism. Braz J Microbiol. 2016;47(2):468–79.

Schirmböck M, Lorito M, Wang YL, Hayes CK, Arisan-Atac I, Scala F, Harman GE, Kubicek CP. Parallel formation and synergism of hydrolytic enzymes and peptaibol antibiotics, molecular mechanisms involved in the antagonistic action of Trichoderma harzianum against phytopathogenic fungi. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4364–70.

Viterbo A, Wiest A, Brotman Y, Chet I, Kenerley C. The 18mer peptaibols from Trichoderma virens elicit plant defence responses. Mol Plant Pathol. 2007;8(6):737–46.

Solfrizzo M, Altomare C, Visconti A, Bottalico A, Perrone G. Detection of peptaibols and their hydrolysis products in cultures of Trichoderma species. Nat Toxins. 1994;2:360–5.

Neuhof T, Dieckmann R, Druzhinina IS, Kubicek CP, von Döhren H. Intact-cell MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis of peptaibol formation by the genus Trichoderma/Hypocrea: can molecular phylogeny of species predict peptaibol structures? Microbiology. 2007;153:3417–37.

Degenkolb T, Karimi Aghcheh R, Dieckmann R, Neuhof T, Baker SE, Druzhinina IS, Kubicek CP, Brückner H, von Döhren H. The production of multiple small peptaibol families by single 14-module peptide synthetases in Trichoderma/Hypocrea. Chem Biodivers. 2012;9(3):499–535.

Jiang CS, Guo YW. Epipolythiodioxopiperazines from fungi: chemistry and bioactivities. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2011;11(9):728–45.

Gardiner DM, Cozijnsen AJ, Wilson LM, Pedras MS, Howlett BJ. The sirodesmin biosynthetic gene cluster of the plant pathogenic fungus Leptosphaeria maculans. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:1307–18.

Gardiner DM, Waring P, Howlett BJ. The epipolythio-dioxopiperazine (ETP) class of fungal toxins: distribution, mode ofaction, functions and biosynthesis. Microbiology. 2005;151:1021–32.

Vargas WA, Mukherjee PK, Laughlin D, Wiest A, Moran-Diez ME, Kenerley CM. Role of gliotoxin in the symbiotic and pathogenic interactions of Trichoderma virens. Microbiology. 2014;160:2319–30.

Varma A. In: Chincholkar SB, editor. Microbial Siderophores. Dordrecht: Springer; 2007. p. 248.

Mercado-Blanco J, Bakker PAHM. Interactions between plants and beneficial Pseudomonas spp.: exploiting bacterial traits for crop protection. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 2007;92:367–89.

Altomare C, Tringovska I. Beneficial soil microorganisms, an ecological alternative for soil fertility management. 2011. In: Lichtfouse E, editor. Genetics, biofuels and local farming systems. Sustainable agriculture reviews, vol. 7. Dordrecht: Springer; 2011. p. 161–214.

Renshaw JC, Robson GD, Trinci APJ, Wiebe MG, Livens FR, Collison D, Taylor RJ. Fungal siderophores: structures, functions and applications. Mycol Res. 2002;106:1123–42.

Lehner SM, Atanasova L, Neumann NK, Krska R, Lemmens M, Druzhinina IS, Schuhmacher R. Isotope-assisted screening for iron-containing metabolites reveals a high degree of diversity among known and unknown siderophores produced by Trichoderma spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:18–31.

Segarra G, Casanova E, Avilés M, Trillas I. Trichoderma asperellum strain T34 controls Fusarium wilt disease in tomato plants in soilless culture through competition for iron. Microb Ecol. 2010;59:141–9.

Vinale F, Ghisalberti EL, Sivasithamparam K, Marra R, Ritieni A, Ferracane R, Woo S, Lorito M. Factors affecting the production of Trichoderma harzianum secondary metabolites during the interaction with different plant pathogens. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2009;48:705–11.

Wallner A, Blatzer M, Schrettl M, Sarg B, Lindner H, Haas H. Ferricrocin, a siderophore involved in intra- and transcellular iron distribution in Aspergillus fumigatus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:4194–6.

Oide S, Krasnoff SB, Gibson DM, Turgeon BG. Intracellular siderophores are essential for ascomycete sexual development in heterothallic Cochliobolus heterostrophus and homo-thallic Gibberella zeae. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:1339–53.

Sharma RP, Kim YM. Trichothecenes. In: Mycotoxins and phytoalexins. Boca Ruton: CRC Press; 1991. p. 339–59.

Reino JL, Guerrero RF, Hernández-Galán R, Collado IG. Secondary metabolites from species of the biocontrol agent Trichoderma. Phytochem Rev. 2008;7:89–123.

Gallo A, Mulé G, Favilla M, Altomare C. Isolation and characterisation of a trichodiene synthase homologous gene in Trichoderma harzianum. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2004;65:11–20.

Cardoza RE, Malmierca MG, Hermosa MR, Alexander NJ, McCormick SP, Proctor RH, Tijerino AM, Rumbero A, Monte E, Gutiérrez S. Identification of loci and functional characterization of trichothecene biosynthesis genes in filamentous fungi of the genus Trichoderma. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(14):4867–77.

Lorito M, Woo SL, Harman GE, Monte E. Translational research on Trichoderma: from ‘omics to the field. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2010;48:395–417.

Afgan E, Baker D, van den Beek M, Blankenberg D, Bouvier D, Čech M, Chilton J, Clements D, Coraor N, Eberhard C, Grüning B, Guerler A, Hillman-Jackson J, Von Kuster G, Rasche E, Soranzo N, Turaga N, Taylor J, Nekrutenko A, Goecks J. The galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W3–W10.

Mitchell A, Chang HY, Daugherty L, Fraser M, Hunter S, Lopez R, McAnulla C, McMenamin C, Nuka G, Pesseat S, Sangrador-Vegas A, Scheremetjew M, Rato C, Yong SY, Bateman A, Punta M, Attwood TK, Sigrist CJ, Redaschi N, Rivoire C, Xenarios I, Kahn D, Guyot D, Bork P, Letunic I, Gough J, Oates M, Haft D, Huang H, Natale DA, Wu CH, Orengo C, Sillitoe I, Mi H, Thomas PD, Finn RD. The InterPro protein families database: the classification resource after 15 years. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D213–21.

Hunter S, Apweiler R, Attwood TK, Bairoch A, Bateman A, Binns D, Bork P, Das U, Daugherty L, Duquenne L, Finn RD, Gough J, Haft D, Hulo N, Kahn D, Kelly E, Laugraud A, Letunic I, Lonsdale D, Lopez R, Madera M, Maslen J, McAnulla C, McDowall J, Mistry J, Mitchell A, Mulder N, Natale D, Orengo C, Quinn AF, Selengut JD, Sigrist CJ, Thimma M, Thomas PD, Valentin F, Wilson D, Wu CH, Yeats C. InterPro: the integrative protein signature database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D211–5.

Hu Z-L, Bao J, Reecy JM. CateGOrizer: a web-based program to batch analyze gene ontology classification categories. Onl J Bioinfor. 2008;9(2):108–12.

Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8:785–6.

Yin Y, Mao X, Yang JC, Chen X, Mao F, Xu Y. dbCAN: a web resource for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Web Server issue):W445–51.

Stanke M, Waack S. Gene prediction with a hidden Markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:215–25.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by H2020-E.U.3.2-678781-MycoKey - Integrated and innovative key actions for mycotoxin management in the food and feed chain.

We are thankful to Dr. Matteo Chiara of University of Milan for the bioinformatic assistance.

Funding

The present work has received funding by the European Union’s Horizon2020 Research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No.678781 (MycoKey). The funding body did not exert influence on the design of the study, and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files]. This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession PNRQ00000000. The version described in this paper is version PNRQ01000000.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CA conceived the work and interpreted the data. FF and VCL performed the genomic sequencing and the bioinformatic analyses. AFL organized and supervised the bioinformatic work. CA and FF wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

The file contains the multi sequence alignment of ITS-TEF1 concatenated datasets used for the phylogenetic analysis of Trichoderma spp. (MAS 69 kb)

Additional file 2:

Trichoderma atrobrunneum ITEM 908 protein sequences: the file contains the multifasta of the proteins predicted by Augustus [100] implemented in the Galaxy platform (Galaxy tool Version 1.0.0) (FASTA 5102 kb)

Additional file 3:

The file contains gene coordinates of Trichoderma atrobrunneum ITEM 908. (GTF 26492 kb)

Additional file 4:

The file contains the PFAM functional domains of Trichoderma atrobrunneum ITEM 908 predicted by the PFAM annotator tool implemented in the Galaxy platform (Galaxy tool Version 1.0.0). (TXT 1927 kb)

Additional file 5:

Table S1. Comparative analysis of PFAM domains associated to CAZYmes in Trichoderma spp. (XLSX 42 kb)

Additional file 6:

Table S2. Terpene synthase (TS), non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS), polyketide synthase (PKS) and hybrid PKS-NRPS genes identified in the genome of T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908, predicted protein sequences, their putative orthologue and % of identity in Trichoderma spp. (XLSX 54 kb)

Additional file 7:

Figure S1. The putative conidial pigment PKS gene clusters of Trichoderma spp. Numbers over the arrows in T. virens and T. reesei indicated the ID of genes as reported in Ensembl Fungi©. Numbers over the arrows in T. atrobrunneum indicated the ID of genes as predicted by Augustus [100]. (PNG 844 kb)

Additional file 8:

Figure S2. Ferricrocin gene cluster in T. atrobrunneum ITEM 908. ALDH: aldehyde dehydrogenase; OXD: oxidoreductase; NRPS: non-ribosomal peptide synthetase; OMO: ornithine monooxygenase; TF: transcription factor. (PNG 142 kb)

Additional file 9:

Table S3. Trichoderma spp. and genomic sequences accession used in this study. (DOCX 13 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article