Abstract

Introduction

Biphasic positive airway pressure (BIVENT) is a partial support mode that employs pressure-controlled, time-cycled ventilation set at two levels of continuous positive airway pressure with unrestricted spontaneous breathing. BIVENT can modulate inspiratory effort by modifying the frequency of controlled breaths. Nevertheless, the optimal amount of inspiratory effort to improve respiratory function while minimizing ventilator-associated lung injury during partial ventilatory assistance has not been determined. Furthermore, it is unclear whether the effects of partial ventilatory support depend on acute lung injury (ALI) etiology. This study aimed to investigate the impact of spontaneous and time-cycled control breaths during BIVENT on the lung and diaphragm in experimental pulmonary (p) and extrapulmonary (exp) ALI.

Methods

This was a prospective, randomized, controlled experimental study of 60 adult male Wistar rats. Mild ALI was induced by Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide either intratracheally (ALIp) or intraperitoneally (ALIexp). After 24 hours, animals were anesthetized and further randomized as follows: (1) pressure-controlled ventilation (PCV) with tidal volume (Vt) = 6 ml/kg, respiratory rate = 100 breaths/min, PEEP = 5 cmH2O, and inspiratory-to-expiratory ratio (I:E) = 1:2; or (2) BIVENT with three spontaneous and time-cycled control breath modes (100, 75, and 50 breaths/min). BIVENT was set with two levels of CPAP (Phigh = 10 cmH2O and Plow = 5 cmH2O). Inspiratory time was kept constant (Thigh = 0.3 s).

Results

BIVENT was associated with reduced markers of inflammation, apoptosis, fibrogenesis, and epithelial and endothelial cell damage in lung tissue in both ALI models when compared to PCV. The inspiratory effort during spontaneous breaths increased during BIVENT-50 in both ALI models. In ALIp, alveolar collapse was higher in BIVENT-100 than PCV, but decreased during BIVENT-50, and diaphragmatic injury was lower during BIVENT-50 compared to PCV and BIVENT-100. In ALIexp, alveolar collapse during BIVENT-100 and BIVENT-75 was comparable to PCV, while decreasing with BIVENT-50, and diaphragmatic injury increased during BIVENT-50.

Conclusions

In mild ALI, BIVENT had a lower biological impact on lung tissue compared to PCV. In contrast, the response of atelectasis and diaphragmatic injury to BIVENT differed according to the rate of spontaneous/controlled breaths and ALI etiology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mechanical ventilation with low tidal volume (Vt), limited inspiratory pressure and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) are commonly used in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) to minimize alveolar atelectasis and overdistension [1, 2]. Protective ventilation is usually associated with controlled modes of mechanical ventilation that may require high-dose sedation and neuromuscular blockade and may also lead to respiratory muscle atrophy, hemodynamic impairment and prolonged weaning [3]. Furthermore, controlled mechanical ventilation may enhance alveolar collapse and inhomogeneity of the lung parenchyma, inducing further lung damage [4].

Partial ventilatory support allows spontaneous breathing efforts during mechanical ventilation, reducing sedation requirements and the need for muscle paralysis, thus minimizing hemodynamic impairment [5] and respiratory muscle dysfunction [3]. In addition, spontaneous breathing has a potentially protective effect on the lung parenchyma resulting from decreased atelectasis and improved ventilation distribution [6]. However, spontaneous breathing activity has the potential to increase transpulmonary pressure (PL) and patient–ventilator asynchrony, thereby worsening lung injury and patient outcome in severe ARDS cases [7, 8].

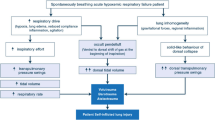

Biphasic positive airway pressure (BIVENT) is a partial support mode that employs pressure-controlled, time-cycled ventilation set at two levels of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) with unrestricted spontaneous breathing. It may be used in any phase of the mechanical ventilatory cycle. Biphasic positive airway pressure is able to modulate the inspiratory effort by modifying the frequency of controlled breaths. Nevertheless, the optimal amount of inspiratory effort to improve respiratory function while minimizing ventilator-associated lung injury (VALI) during partial ventilatory assistance has not been determined. Moreover, it is unclear whether the effects of partial ventilatory support depend on ARDS etiology. Theoretically, pulmonary ARDS (ARDSp) involves higher degrees of lung tissue consolidation, whereas extrapulmonary ARDS (ARDSexp) is associated mainly with alveolar collapse, which can potentially be overcome by increased inspiratory effort [9].

In the present study, we investigated the impact of inspiratory effort during biphasic positive airway pressure on lung morphology and function, markers of inflammation, fibrosis, apoptosis, endothelial and epithelial cell damage, and diaphragmatic injury in experimental pulmonary and extrapulmonary acute lung injury (ALIp and ALIexp, respectively). We hypothesized that biphasic positive airway pressure would (1) improve lung function and reduce VALI compared to pressure-controlled ventilation (PCV), (2) modulate lung injury according to the frequency of time-cycled control breaths and inspiratory effort and (3) have etiology-dependent effects on breathing patterns, lung mechanics, histology and biochemical response.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro Health Sciences Center. All animals received humane care in compliance with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care formulated by the National Society for Medical Research and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences.

Animal preparation and experimental protocol

Sixty adult male Wistar rats (250 to 300 g) were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions in an animal care facility at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. Mild ALI was induced in all animals by Escherichia coli O55:B5 lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Because ALI etiology might entail different effects of partial ventilatory support, both ALIp and ALIexp were induced by intratracheal or intraperitoneal injection of E. coli LPS (200 μg for ALIp and 1,000 μg for ALIexp suspended in saline solution with total volumes equal to 100 μl and 1,000 μl, respectively) [10]. The animals were randomly allocated to the ALIp or ALIexp group.

Twenty-four hours after ALI induction, the rats were sedated (10 mg/kg diazepam intraperitoneally), anesthetized (100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine intraperitoneally) and tracheotomized. Twelve of the sixty rats (n = 6 per ALI etiology) were used for electron microscopy and molecular biology analysis and were not mechanically ventilated (nonventilated, NV).

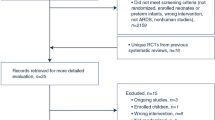

A polyethylene catheter (PE-10) was introduced into the carotid artery for blood sampling and monitoring of mean arterial pressure (MAP). Electrocardiograms, MAP and rectal temperature were continuously recorded (Networked Multi-Parameter Veterinary Monitor LifeWindow 6000 V; Digicare Animal Health, Boynton Beach, FL, USA). The tail vein was punctured for continuous infusion of Ringer’s lactate solution (10 ml/kg/h). Gelafundin (B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) was administered (in 0.5-ml increments) to keep MAP above 70 mmHg. Animals were mechanically ventilated (SERVO-i; MAQUET, Solna, Sweden) in volume-controlled mode at the following settings: Vt = 6 ml/kg, respiratory rate (RR) = 100 breaths/min, fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) = 1.0, inspiratory-to-expiratory ratio (I:E) = 1:2 and zero end-expiratory pressure (ZEEP) during five minutes. Arterial blood (300 μl) was drawn into a heparinized syringe for measurement of arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2), partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) and arterial pH (pHa) (i-STAT; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA) (baseline ZEEP). Following this step, the animals were randomly assigned to one of the following mechanical ventilation groups: (1) PCV mode with Vt = 6 ml/kg, RR = 100 breaths/min, PEEP = 5 cmH2O and I:E = 1:2, during which animals were paralyzed with pancuronium bromide (2 mg/kg intravenously); or (2) BIVENT with three different rates of time-cycled control breaths (100, 75 and 50 breaths/min). In both groups, BIVENT was set at two levels of CPAP (Phigh = 10 cmH2O and Plow = 5 cmH2O). Inspiratory time was kept constant (Thigh = 0.3 seconds). Both ventilator strategies were maintained with FiO2 = 0.4 for one hour. FiO2 was then set at 1.0 for five minutes, and arterial blood gases were analyzed (End). Lungs were extracted for histological and molecular biological analysis. Schematic flowcharts of the study design and the timeline representation of the procedures are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Schematic flowchart of study design. ALIexp: extrapulmonary acute respiratory distress syndrome; ALIp: pulmonary acute respiratory distress syndrome; BIVENT: biphasic positive airway pressure at different rates of time-cycled controlled breaths (100, 75 and 50 breaths/min); E. coli LPS: Escherichia coli O55:B5 lipopolysaccharide; i.p.: intraperitoneal; i.t.: intratracheal; NV: nonventilated; PCV: pressure-controlled ventilation.

Timeline of the procedure. ALI: acute lung injury; APCV: assisted pressure-controlled ventilation; BIVENT: biphasic positive airway pressure; FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; PCV: pressure-controlled ventilation; PEEP: positive end-expiratory pressure; Vt: tidal volume; ZEEP: zero end-expiratory pressure.

Data acquisition and processing

After one hour of mechanical ventilation, all variables were recorded for ten minutes. Airway pressure (Paw) was measured with a differential pressure transducer (UT-PDP-300; SCIREQ, Montreal, QC, Canada). Changes in esophageal pressure (Pes), which reflect chest wall pressure, were measured with a 30-cm-long, water-filled catheter (PE205) with side holes at the tip connected to a differential pressure transducer (UT-PL-400; SCIREQ). The catheter was passed into the stomach and then slowly withdrawn back into the esophagus. Its proper positioning was assessed using the occlusion test [11]. Vt was calculated by digital integration of the flow signal. PL was calculated during inspiration and expiration as the difference between tracheal and esophageal pressure. Mean airway pressure (Pmean,aw) and peak airway pressure (Ppeak,aw) were calculated. The total RR was calculated from the Pes swings as the frequency per minute of each type of breathing cycle. The pressure–time product (PTP) per breath was calculated as the integral of ∆Pes over time. ∆Pes was measured from the beginning of inspiration during each type of breathing cycle, independent of the CPAP level. Total ventilation (V′e,tot) and PTP per minute were calculated by multiplying the Vt and PTP by the corresponding frequency at one minute for each breathing cycle, respectively. RR, Vt, V′e, and PTP were calculated for three different types of breathing cycles as follows: (1) fully controlled cycles (C) as time-cycled breaths that were not accompanied by negative Pes swings; (2) spontaneous breath cycles at high and low CPAP levels (Phigh and Plow, respectively) as negative Pes swings not followed by ventilator cycling; and (3) mixed respiratory cycles (M) as negative Pes swings with simultaneous ventilator inspiratory cycling (Figure 3).

Original tracheal, esophageal and transpulmonary pressure and airflow tracings. Top panel: Original tracings of tracheal (black line), esophageal (red line) and transpulmonary (green line) pressure. Note the two levels of continuous positive airway pressure (Phigh = 10 cmH2O and Plow = 5 cmH2O) in controlled and mixed cycles (blue boxes). Black arrows in top and middle panels indicate beginning of inspiration. Middle panel: Original tracings of tracheal (black line), esophageal (red line) and transpulmonary (green line) pressure at different rates of time-cycled controlled breaths: 100, 75 and 50 breaths/min. Bottom panel: Original tracings of esophageal and transpulmonary pressure and airflow. Blue circles: PTP area. BIVENT: biphasic positive airway pressure; Phigh: high level of continuous positive airway pressure; Plow: low level of continuous positive airway pressure; PTP: pressure–time product per breath.

Airflow, tracheal and esophageal pressure were continuously recorded throughout the experiments with a computer running software written in LabVIEW (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). All signals were filtered (200 Hz), amplified by a four-channel conditioner (SC-24; SCIREQ) and sampled at 200 Hz with a 12-bit analog-to-digital converter (National Instruments). All mechanical data were computed offline by a routine written in MATLAB software (version R2007a; The MathWorks Inc, Natick, MA, USA).

Histology

Light microscopy

A laparotomy was performed immediately after blood sampling at the end of the experiments. Heparin (1,000 IU) was injected into the tail vein. Sodium thiopental (25 mg/ml) was injected to increase the level of anesthesia, and the trachea was then clamped at end expiration (PEEP = 5 cmH2O). The abdominal aorta and vena cava were sectioned, yielding a massive hemorrhage that quickly killed the animals. Lungs were removed en bloc with end expiratory pressure of 5 cmH2O in all groups to avoid distortion of lung morphometry. The left lung was frozen in liquid nitrogen and immersed in Carnoy’s solution. Lung morphometric analysis was performed using an integrating eyepiece with a coherent system consisting of a grid with 100 points and 50 lines of known length coupled to a conventional light microscope (Olympus BX51; Olympus Latin America, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). The volume fractions of the lung occupied by collapsed alveoli, normal pulmonary areas or hyperinflated structures (alveolar ducts, alveolar sacs or alveoli; maximal chord length in air greater than 120 μm) were determined by the point-counting technique at a magnification of ×200 across ten random, noncoincident microscopic fields [12].

Transmission electron microscopy

Three slices measuring 2 × 2 × 2 mm each were cut from three different segments of the right lung and diaphragm. They were then fixed (2.5% glutaraldehyde and phosphate buffer 0.1 M, pH 7.4) for electron microscopy analysis (JEOL 1010 Transmission Electron Microscope; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). For each electron microscopy image (20 per animal), an injury score was calculated. The following parameters were analyzed concerning lung parenchyma: damage to alveolar capillary membrane, type II epithelial cell lesion and endothelial cell damage [10]. The following aspects were assessed on the basis of electron microscopy of the diaphragm muscle: (1) myofibrillar abnormalities, defined as disruption of myofibrillar bundles or disorganized myofibrillar pattern with edema of the Z disks, a filamentous network of proteins forming a disklike structure for the attachment of actin myofilaments (The Z disks provide structural linkage for the transmission of tension and contractile forces along the muscle fiber and play a role in sensing muscle activity and signal transduction); (2) mitochondrial injury with abnormal, swollen mitochondria and abnormal cristae; and (3) miscellaneous, which included lipid droplets, vacuoles, intermyofibril space and nuclei. The pathological findings were graded according to a five-point, semiquantitative, severity-based scoring system expressed as percentage of examined tissue: 0 = normal lung parenchyma or diaphragm, 1 = changes in 1% to 25%, 2 = changes in 26% to 50%, 3 = changes in 51% to 75% and 4 = changes in 76% to 100%. The pathologist or technician working on the electron microscopy images was blinded to the nature of the study.

Biological markers of apoptosis, fibrogenesis and lung epithelial and endothelial cell damage

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reactions were performed to measure biological markers associated with apoptosis (procaspase 3); fibrogenesis (type III procollagen, PCIII); damage inflicted on alveolar type I (receptor for advanced glycation end product, RAGE) and alveolar type II epithelial cells (surfactant protein B); and endothelium (vascular cellular adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) [13] (Table 1). Central slices of right lung tissue were cut, collected in cryotubes, quick-frozen by immersion in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C. Total RNA was extracted from frozen tissue using the SV Total RNA Isolation System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), following the manufacturer’s recommendations. RNA concentration was measured by spectrophotometry in a NanoDrop ND-1000 System (NanoDrop Products, Wilmington, DE, USA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using the GoTaq 2-Step RT-qPCR System (Promega). Relative mRNA levels were measured by SYBR Green–based detection using the ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Samples were measured in triplicate. For each sample, the expression of each gene was normalized to housekeeping gene expression (acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein P0, 36B4) using the 2-ΔΔCt method, where ΔCt = Ct (reference gene) - Ct (target gene).

Statistical analysis

Data were tested for normal distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with Lilliefors correction) and homogeneity of variances (Levene median test). If both conditions were met, the effects of different ventilatory strategies on ALI groups were analyzed by means of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s test. Otherwise, one-way ANOVA on ranks followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was employed. The significance level was always set at 5%. Parametric data were expressed as means ± SD, and nonparametric data were expressed as medians (IQR). All tests were performed using SigmaStat 3.1 software (Jandel Corp, San Raphael, CA, USA).

Results

Mean arterial pressure was higher than 70 mmHg throughout the experiments in both ALI groups, but was significantly lower during PCV than during BIVENT (Figure 4). In the ALIexp group, animals required additional fluid administration to keep MAP higher than 70 mmHg (P < 0.05).

Mean arterial pressure of animals with pulmonary and extrapulmonary acute respiratory distress syndrome. ALIexp: extrapulmonary acute lung injury; ALIp: pulmonary acute lung injury; BIVENT: biphasic positive airway pressure; MAP: mean arterial pressure; PCV: pressure-controlled ventilation. Values are means ± SD of six rats at each time point. #Significantly different from PCV (P < 0.05).

At baseline, the overall respiratory mechanics parameters were comparable among groups, except for PTP, which was lower for BIVENT-100 in the ALIp group (Table 2). At the end of the experiment, minutes on ventilation, mean Vt and peak airway pressure were comparable in the PCV and BIVENT groups, regardless of ALI etiology. The RR of spontaneous breaths, minutes on ventilation, PTP/min and P0.1 during Plow were significantly increased for BIVENT-50 compared to BIVENT-75 and BIVENT-100. Inspiratory pressure and mean airway pressure were similar in all assisted ventilation modes (Table 3). However, with regard to spontaneous breaths during Plow, P0.1 was higher for BIVENT-50 than for BIVENT-75 and BIVENT-100. PaO2, PaCO2 and pHa at baseline ZEEP and after one hour of ventilation (End) did not differ among ventilation strategies and ALI groups (Table 4).

In ALIp, alveolar collapse was higher at BIVENT-100 compared to PCV and lower at BIVENT-50 than at BIVENT-100 and BIVENT-75. In ALIexp, alveolar collapse was lower at BIVENT-50 than the other ventilatory strategies (Table 5 and Figure 5).

Photomicrographs of lung parenchyma stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Photomicrographs are representative of data obtained from lung sections of six animals (original magnification, ×200). ALIexp: extrapulmonary acute lung injury; ALIp: pulmonary acute lung injury; BIVENT: biphasic positive airway pressure at different rates of time-cycled controlled breaths: 100, 75 and 50 breaths/min; NV: nonventilated; PCV: pressure-controlled ventilation.

The semiquantitative analysis of lung and diaphragm electron microscopy is shown in Table 6 and Figures 6 and 7. In the ALIp group, BIVENT-75 and BIVENT-50 resulted in reduced damage to alveolar capillary membranes, type II epithelial cells and endothelial cells compared to PCV. In ALIexp, BIVENT-75 reduced type II epithelial and endothelial cell damage, and BIVENT-50 reduced alveolar capillary membrane and type II epithelial cell damage, compared to PCV. In ALIp, mechanical ventilation led to myofibril damage with Z-disk edema, which was greater under PCV and BIVENT-100 than with other ventilator strategies. Mitochondrial injury of the diaphragm was less pronounced with BIVENT-50 than with BIVENT-100. Vacuoles were more abundant under PCV than under NV. BIVENT-50 resulted in a lower number of vacuoles and less diaphragm damage than other ventilator strategies. In the ALIexp group, Z-disk edema was more pronounced during PCV and BIVENT-50 than during NV. Mitochondrial injury was more intense under PCV than under NV, but there were no differences in mitochondrial injury among different ventilator strategies. BIVENT-100 and BIVENT-75 resulted in fewer vacuoles and less intermyofibril space than were caused by PCV.

Electron microscopy of lung parenchyma. Photomicrographs are representative of data obtained from lung sections of five animals per group. Black arrows: alveolar capillary basement (ACB) membrane. Note that endothelial cells as well as alveolar types I and II epithelial cells were injured. ALIexp: extrapulmonary acute lung injury; ALIp: pulmonary acute lung injury; AS = intra-alveolar space; BIVENT: biphasic positive airway pressure at different rates of time-cycled controlled breaths: 100, 75 and 50 breaths/min; Cap = capillary; E = erythrocyte; ED = edema; NV: nonventilated; P2 = type II epithelial cell; PCV: pressure-controlled ventilation.

Electron microscopy of diaphragm. Photomicrographs are representative of data obtained from diaphragm sections of five animals per group. In ALIp animals ventilated with PCV or BIVENT-100, note the presence of vacuoles. Conversely, in ALIexp, there were more vacuoles in BIVENT-50 compared to BIVENT-100, but a similar amount compared to PCV. ALIexp: extrapulmonary acute lung injury; ALIp: pulmonary acute lung injury; BIVENT: biphasic positive airway pressure at different rates of time-cycled controlled breaths: 100, 75 and 50 breaths/min; NV: nonventilated; PCV: pressure-controlled ventilation.

In both ALI models, BIVENT decreased the gene expression of interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-1β, procaspase 3, PCIII, ICAM-1 and RAGE in lung tissue compared to PCV (Figure 8). In ALIp, gene expression of IL-6 and PCIII was lower in all BIVENT groups compared to PCV. IL-6, ICAM-1 and RAGE mRNA was reduced in BIVENT-75, and gene expression of procaspase 3 was lower in BIVENT-50 compared to PCV. In ALIexp, gene expression of IL-6, PCIII and RAGE was lower in all BIVENT groups compared to PCV. Procaspase 3 gene expression was reduced in BIVENT-75 and BIVENT-50 compared to PCV. Expression of ICAM-1 and IL-1β mRNA was lower in BIVENT-75 and BIVENT-50, respectively, compared to PCV.

Expression of biological markers. Real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis of biological markers associated with inflammation (interleukin β (IL-β) and IL-6), apoptosis (procaspase 3), fibrogenesis (pro-collagen type III, PCIII) and damage inflicted upon the endothelium (intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1)) and alveolar type I epithelial cells (receptor for advanced glycation end product, RAGE). Relative gene expression was calculated as a ratio of the average gene expression levels compared with the reference gene (36B4) and expressed as fold change relative to NV (nonventilated). ALIexp: extrapulmonary acute lung injury; ALIp: pulmonary acute lung injury; BIVENT: biphasic positive airway pressure at different rates of time-cycled controlled breaths: 100, 75 and 50 breaths/min; NV: nonventilated; P2 = type II epithelial cell; PCV: pressure-controlled ventilation. Boxplots show medians and IQRs of five rats in each group. *P < 0.05 vs. NV, #P < 0.05 vs. PCV.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that BIVENT promoted a more pronounced reduction in markers of inflammation, apoptosis and fibrogenesis, as well as less epithelial and endothelial cell damage, in rat models of ALIp and ALIexp compared to PCV. Conversely, the rate of spontaneous and assisted breaths during BIVENT led to etiology-associated levels of atelectasis and diaphragmatic injury. In ALIp, alveolar collapse increased during BIVENT-100 but decreased during BIVENT-50 compared to PCV, and there was less diaphragmatic injury during BIVENT-50. In ALIexp, alveolar collapse during BIVENT-100 and BIVENT-75 was comparable to PCV but was decreased during BIVENT-50 compared to PCV, and diaphragmatic injury increased during BIVENT-50.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous experimental study has investigated the biological impact of different rates of time-cycled control breaths during BIVENT on lung morphology, inflammation, apoptosis, fibrogenesis, epithelial and endothelial cell damage and diaphragmatic damage in ALIp and ALIexp. In fact, PCV has been compared with BIVENT combined with pressure support at a constant rate of time-cycled control breaths [4], as well as with pressure support alone [14], but those studies did not address the etiology of ALI. In clinical practice, ALIp and ALIexp can overlap and their distinction is not always easy. However, the use of these two models of mild ALI might improve understanding of the mechanisms of VALI during assisted ventilation.

In our ALIp and ALIexp models, gene expression of inflammatory mediators, apoptosis, fibrogenesis and biochemical markers of epithelial and endothelial cell injury decreased during BIVENT compared to PCV, but did not differ between varying rates of time-cycled control breaths. BIVENT-75 and BIVENT-50 reduced ultrastructural damage to the alveolar capillary membrane and to type II epithelial and endothelial cells. Furthermore, BIVENT was associated with a reduction in gene expression of markers of endothelial and epithelial cell damage. Thus, our results suggest that the presence of spontaneous and assisted breaths is sufficient to minimize VALI compared to PCV, regardless of the level of inspiratory effort. This indicates that the reduction of atelectasis per se cannot explain the reduction in VALI observed with BIVENT. Accordingly, it is conceivable that other mechanisms play a role, such as more homogeneous distribution of ventilation and regional pleural pressure, as well as redistribution of perfusion [15–17].

We observed that, compared to modes with spontaneous breathing activity, PCV induced damage to the diaphragm. This finding is consistent with reports of several studies that have shown less diaphragmatic injury during assisted ventilation [18, 19]. Sassoon et al. showed that partial respiratory muscle activation reduces muscle dysfunction in other ALI models [20]. Nevertheless, BIVENT-50 was associated with increased diaphragm injury in ALIexp, as evidenced by augmented vacuolization, but not in ALIp. A possible explanation is that the amount of muscle work during spontaneous breath cycles was relatively low in animals with ALIexp that were ventilated with BIVENT-50, favoring diaphragmatic dysfunction. However, not only the amount of inspiratory effort but also RR per se may affect diaphragmatic injury. These data could have a potential impact on further investigations into this specific issue and highlight the importance of monitoring and evaluating RR during assisted ventilation. Our results suggest that controlled breaths during BIVENT should be cautiously reduced in ALIexp to minimize diaphragmatic injury.

Pulmonary and extrapulmonary mild ALI were induced by administering E. coli LPS intratracheally and intraperitoneally, respectively. Both models cause similar deterioration in oxygenation, lung mechanics and alveolar collapse [9, 21]. The LPS model reproduces some of the main features of ALI, such as histological tissue injury, alteration of the alveolar capillary barrier, inflammation and pulmonary dysfunction [22]. Direct lung injury (ALIp) primarily affects the alveolar epithelium, with damage occurring mainly in the intra-alveolar space, with alveolar flooding and areas of consolidation [9, 21]. In indirect lung injury (ALIexp), endothelial cells are the first target of damage, with a subsequent increase in vascular permeability. Thus, the main pathologic alteration due to an indirect insult may be microvessel congestion and interstitial edema, with relative sparing of intra-alveolar spaces [9]. In view of these facts, we hypothesized that BIVENT would be more effective to reopen atelectatic lung regions (thus resulting in less VALI) in ALIexp as compared to ALIp.

In line with current recommendations [23], we used protective mechanical ventilation with the same driving pressure to achieve a low Vt (6 ml/kg) during both PCV and BIVENT. The level of PEEP was set at 5 cmH2O because previous observations from our group suggested that higher levels may lead to hyperinflation and lung injury in these models of ALI in rats [10, 21]. Unlike other types of biphasic CPAP ventilation, BIVENT allows spontaneous breaths not only during low levels of CPAP but also during high levels. Thus, ineffective breaths are avoided during the high level of CPAP. During BIVENT, inspiratory time was kept constant while changing the rate of time-cycled breaths to allow more spontaneous breaths during the low level of CPAP. The choice of ventilation settings of BIVENT was guided by our clinical experience with ARDS patients. Accordingly, we used a RR yielding full support (100%), that is, controlled mechanical ventilation, as well as half (50%) of that rate. To avoid excessive inspiratory effort and muscular fatigue, we did not use lower RRs. To minimize asynchrony, no pressure support was used during spontaneous breaths. Blood gas analysis was performed with FiO2 = 1.0 to avoid possible confounding effects of ventilation/perfusion mismatch in the interpretation of the gas exchange data [24]. However, this study was conducted with FiO2 = 0.40 to avoid possible iatrogenic effects on the lung parenchyma induced by high concentrations of oxygen [25]. Because pulmonary histology was evaluated at comparable airway pressures, lung morphometry changes mainly reflect the effects of different modes of mechanical ventilation.

Arterial blood gases were analyzed separately at baseline ZEEP and at end (PEEP = 5 cmH2O) in each ALI group. The dramatic recovery in oxygenation over one hour of mechanical ventilation may suggest that the hypoxemia is a consequence of atelectasis. Hypoxemia would undoubtedly occur in rodents subjected to anesthesia, surgery and mechanical ventilation with ZEEP, which favors the use of recruitment maneuvers (RMs). However, we previously observed that RMs resulted in greater type III procollagen mRNA expression in ALIp than in ALIexp[14], and thus we avoided such maneuvers in the present study. Moreover, our goal was to investigate the role of different amount of assisted spontaneous breaths on lung injury, taking into account all the limitations of the experimental setting we used.

We found that, in both ALIp and ALIexp, the decrease in the rate of time-cycled control breaths yielded an increase in aeration and a reduction in alveolar collapse. However, in ALIp, we observed an increase in alveolar collapse during BIVENT-100 compared to PCV, without impairment of gas exchange.

The main determinant of alveolar recruitment is the PL achieved at end inspiration and end expiration [26]. Although the inspiratory airway and PL are closely related during controlled mechanical ventilation, they can be partially dissociated during assisted ventilation, owing to respiratory muscle activation. Therefore, we measured Pes as an estimate of the inspiratory effort during BIVENT. The total PTP did not differ between BIVENT groups, whereas PTP during spontaneous breaths at Plow was increased in BIVENT-50 compared to other groups. Respiratory drive, as assessed by P0.1, was higher during BIVENT-50 compared to BIVENT-100 in both ALI models. However, in spontaneous breaths at Plow, P0.1 was higher in BIVENT-50 compared to BIVENT-75 and BIVENT-100. The higher inspiratory effort during BIVENT-50 probably accounts for the reduced alveolar collapse in that group.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. (1) We used intratracheally or intraperitoneally injected E. coli LPS to induce mild pulmonary and extrapulmonary ALI. Thus, these data cannot be extrapolated to ALI models with different degrees of severity or to human ARDS. Nevertheless, our results improve the understanding of the mechanisms underlying VALI during assisted ventilation. (2) ALI was characterized on the basis of the presence of diffuse alveolar damage observed with light and electron microscopy as well as lung functional changes. We did not evaluate the extent of alveolar edema using the wet-to-dry ratio and the level of protein in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. (3) We investigated the effects of different ventilator strategies in ALIp and ALIexp and therefore did not include a control group. This was done mainly to avoid an excessive number of comparisons and because we were interested in investigating the effects of different levels of spontaneous breaths in injured lungs. Furthermore, PEEP was not individually titrated, rather, a fixed PEEP level (5 cmH2O) was applied to avoid the introduction of a confounding factor. (4) The study period was short (one hour); therefore, our results cannot be extrapolated to longer periods of ventilation. However, the advantage of this short duration of mechanical ventilation is that it hinders the introduction of any additional potential factors which may affect the results, such as changes in respiratory pattern and/or hemodynamic instability, fluid overload and/or excessive sedation. (5) We conducted the experiments in small animals, and results may differ in larger animals and patients. (6) Our results are based on BIVENT and cannot be generalized to other modes of assisted ventilation and/or different ventilator settings. (7) Phigh was kept constant during BIVENT. Thus, Vt changed accordingly. On the other hand, when maintaining Vt constant, Phigh may change. In this line, changes in both Vt and Phigh may yield VALI. However, Vt of mechanically controlled breaths was comparable among the different rates of time-cycled controlled breaths. (8) We did not measure inflammatory mediators in blood or distal organs. (9) We avoided a formal evaluation of asynchrony events, because we did not record the electrical activity of the diaphragm. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out an effect of subject–ventilator asynchrony on lung injury outcomes, but any such effect would likely be minor, since spontaneous breathing activity was associated with less lung injury than controlled mechanical ventilation. (10) Ultrastructural damage to the diaphragm was evaluated by semiquantitative analysis. Further studies are required to investigate functional activity and biochemical injury of the diaphragm during longer periods of mechanical ventilation.

Conclusions

In the present models of mild ALI, we found that BIVENT had lower biological impacts than PCV on lung tissue. Atelectasis and diaphragmatic injury resulting from different rates of spontaneous and assisted breaths during BIVENT were dependent on ALI etiology (pulmonary or extrapulmonary). Therefore, care should be taken when setting controlled breaths during BIVENT in ALI.

Key messages

-

In experimental models of mild pulmonary and extrapulmonary ALI, BIVENT had less biological impact than PCV on lung tissue.

-

The inspiratory effort during spontaneous breaths increased during BIVENT with a rate of time-cycled control breaths of 50/min (BIVENT-50) in both ALI models.

-

In ALIp, alveolar collapse was higher in BIVENT-100 than in PCV, but it was decreased during BIVENT-50. In ALIexp, however, alveolar collapse during BIVENT-100 and BIVENT-75 was comparable to PCV but decreased during BIVENT-50.

-

The diaphragmatic injury response to BIVENT differed according to the rate of spontaneous and controlled breaths and to ALI etiology.

Abbreviations

- ACB:

-

Alveolar capillary basement

- ALI:

-

Acute lung injury

- ALIexp:

-

Extrapulmonary acute lung injury

- ALIp:

-

Pulmonary acute lung injury

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BIVENT:

-

Biphasic positive airway pressure

- CPAP:

-

Continuous positive airway pressure

- FiO2:

-

Fraction of inspired oxygen

- ICAM-1:

-

intracellular adhesion molecule 1

- I:E:

-

Inspiratory:expiratory ratio

- MAP:

-

Mean arterial pressure

- NV:

-

Nonventilated

- P0.1:

-

Decay in airway pressure 100 ms after start of inspiration

- PaCO2:

-

Partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide

- PaO2:

-

Partial pressure of arterial oxygen

- PCV:

-

Pressure-controlled ventilation, PEEP, Positive end-expiratory pressure

- pHa:

-

Arterial pH

- Pmean:

-

Mean airway pressure

- Ppeak:

-

Peak airway pressure

- Ppl:

-

mean: Mean transpulmonary pressure

- PSV:

-

Pressure support ventilation

- PTP:

-

pressure–time product of the inspiratory esophageal pressure

- RAGE:

-

Receptor for advanced glycation end product

- RM:

-

Recruitment maneuver

- RR:

-

Respiratory rate

- Ti/Ttot:

-

Inspiratory to total respiratory time

- VALI:

-

Ventilator-associated lung injury

- VCAM-1:

-

Vascular cellular adhesion molecule 1

- Vt:

-

Tidal volume

- ZEEP:

-

Zero end-expiratory pressure.

References

Esteban A, Ferguson ND, Meade MO, Frutos-Vivar F, Apezteguia C, Brochard L, Raymondos K, Nin N, Hurtado J, Tomicic V, González M, Elizalde J, Nightingale P, Abroug F, Pelosi P, Arabi Y, Moreno R, Jibaja M, D’Empaire G, Sandi F, Matamis D, Montañez AM, Anzueto A, VENTILA Group: Evolution of mechanical ventilation in response to clinical research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008, 177: 170-177. 10.1164/rccm.200706-893OC

Needham DM, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, Dinglas VD, Sevransky JE, Dennison Himmelfarb CR, Desai SV, Shanholtz C, Brower RG, Pronovost PJ: Lung protective mechanical ventilation and two year survival in patients with acute lung injury: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2012, 344: e2124. 10.1136/bmj.e2124

Jaber S, Jung B, Matecki S, Petrof BJ: Clinical review: ventilator-induced diaphragmatic dysfunction—human studies confirm animal model findings! Crit Care 2011, 15: 206. 10.1186/cc10023

Saddy F, Oliveira GP, Garcia CS, Nardelli LM, Rzezinski AF, Ornellas DS, Morales MM, Capelozzi VL, Pelosi P, Rocco PR: Assisted ventilation modes reduce the expression of lung inflammatory and fibrogenic mediators in a model of mild acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med 2010, 36: 1417-1426. 10.1007/s00134-010-1808-6

Kaplan LJ, Bailey H, Formosa V: Airway pressure release ventilation increases cardiac performance in patients with acute lung injury/adult respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care 2001, 5: 221-226. 10.1186/cc1027

Wrigge H, Zinserling J, Neumann P, Muders T, Magnusson A, Putensen C, Hedenstierna G: Spontaneous breathing with airway pressure release ventilation favors ventilation in dependent lung regions and counters cyclic alveolar collapse in oleic-acid-induced lung injury: a randomized controlled computed tomography trial. Crit Care 2005, 9: R780-R789. 10.1186/cc3908

Papazian L, Forel JM, Gacouin A, Penot-Ragon C, Perrin G, Loundou A, Jaber S, Arnal JM, Perez D, Seghboyan JM, Constantin JM, Courant P, Lefrant JY, Guérin C, Prat G, Morange S, Roch A, ACURASYS Study Investigators: Neuromuscular blockers in early acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2010, 363: 1107-1116. 10.1056/NEJMoa1005372

Slutsky AS: Neuromuscular blocking agents in ARDS. N Engl J Med 2010, 363: 1176-1180. 10.1056/NEJMe1007136

Rocco PR, Pelosi P: Pulmonary and extrapulmonary acute respiratory distress syndrome: myth or reality? Curr Opin Crit Care 2008, 14: 50-55. 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282f2405b

Santos CL, Moraes L, Santos RS, Oliveira MG, Silva JD, Maron-Gutierrez T, Ornellas DS, Morales MM, Capelozzi VL, Jamel N, Pelosi P, Rocco PR, Garcia CS: Effects of different tidal volumes in pulmonary and extrapulmonary lung injury with or without intraabdominal hypertension. Intensive Care Med 2012, 38: 499-508. 10.1007/s00134-011-2451-6

Baydur A, Behrakis PK, Zin WA, Jaeger M, Milic-Emili J: A simple method for assessing the validity of the esophageal balloon technique. Am Rev Respir Dis 1982, 126: 788-791.

Hsia CC, Hyde DM, Ochs M, Weibel ER, ATS/ERS Joint Task Force on Quantitative Assessment of Lung Structure: An official research policy statement of the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society: standards for quantitative assessment of lung structure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010, 181: 394-418. 10.1164/rccm.200809-1522ST

Silva PL, Cruz FF, Fujisaki LC, Oliveira GP, Samary CS, Ornellas DS, Maron-Gutierrez T, Rocha NN, Goldenberg R, Garcia CS, Morales MM, Capelozzi VL, Gama de Abreu M, Pelosi P, Rocco PR: Hypervolemia induces and potentiates lung damage after recruitment maneuver in a model of sepsis-induced acute lung injury. Crit Care 2010, 14: R114. 10.1186/cc9063

Spieth PM, Carvalho AR, Güldner A, Kasper M, Schubert R, Carvalho NC, Beda A, Dassow C, Uhlig S, Koch T, Pelosi P, Gama de Abreu M: Pressure support improves oxygenation and lung protection compared to pressure-controlled ventilation and is further improved by random variation of pressure support. Crit Care Med 2011, 39: 746-755. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206bda6

Spieth PM, Güldner A, Beda A, Carvalho N, Nowack T, Krause A, Rentzsch I, Suchantke S, Thal SC, Engelhard K, Kasper M, Koch T, Pelosi P, de Abreu MG: Comparative effects of proportional assist and variable pressure support ventilation on lung function and damage in experimental lung injury. Crit Care Med 2012, 40: 2654-2661. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182592021

Gama de Abreu M, Güldner A, Pelosi P: Spontaneous breathing activity in acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2012, 25: 148-155. 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3283504bde

Gama de Abreu M, Cuevas M, Spieth PM, Carvalho AR, Hietschold V, Stroszczynski C, Wiedemann B, Koch T, Pelosi P, Koch E: Regional lung aeration and ventilation during pressure support and biphasic positive airway pressure ventilation in experimental lung injury. Crit Care 2010, 14: R34. 10.1186/cc8912

Picard M, Jung B, Liang F, Azuelos I, Hussain S, Goldberg P, Godin R, Danialou G, Chaturvedi R, Rygiel K, Matecki S, Jaber S, Des Rosiers C, Karpati G, Ferri L, Burelle Y, Turnbull DM, Taivassalo T, Petrof BJ: Mitochondrial dysfunction and lipid accumulation in the human diaphragm during mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012, 186: 1140-1149. 10.1164/rccm.201206-0982OC

Mrozek S, Jung B, Petrof BJ, Pauly M, Roberge S, Lacampagne A, Cassan C, Thireau J, Molinari N, Futier E, Scheuermann V, Constantin JM, Matecki S, Jaber S: Rapid onset of specific diaphragm weakness in a healthy murine model of ventilator-induced diaphragmatic dysfunction. Anesthesiology 2012, 117: 560-567. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318261e7f8

Sassoon CS, Zhu E, Caiozzo VJ: Assist-control mechanical ventilation attenuates ventilator-induced diaphragmatic dysfunction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004, 170: 626-632. 10.1164/rccm.200401-042OC

Riva DR, Oliveira MB, Rzezinski AF, Rangel G, Capelozzi VL, Zin WA, Morales MM, Pelosi P, Rocco PR: Recruitment maneuver in pulmonary and extrapulmonary experimental acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 2008, 36: 1900-1908. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181760e5d

Matute-Bello G, Downey G, Moore BB, Groshong SD, Matthay MA, Slutsky AS, Kuebler WM, Acute Lung Injury in Animals Study Group: An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: features and measurements of experimental acute lung injury in animals. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2011, 44: 725-738. 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0210ST

The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network: Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000, 342: 1301-1308.

Karbing DS, Kjærgaard S, Smith BW, Espersen K, Allerød C, Andreassen S, Rees SE: Variation in the PaO 2 /FiO 2 ratio with FiO 2 : mathematical and experimental description, and clinical relevance. Crit Care 2007, 11: R118. 10.1186/cc6174

Budinger GR, Mutlu GM, Urich D, Soberanes S, Buccellato LJ, Hawkins K, Chiarella SE, Radigan KA, Eisenbart J, Agrawal H, Berkelhamer S, Hekimi S, Zhang J, Perlman H, Schumacker PT, Jain M, Chandel NS: Epithelial cell death is an important contributor to oxidant-mediated acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 183: 1043-1054. 10.1164/rccm.201002-0181OC

Rocco PR, Dos Santos C, Pelosi P: Pathophysiology of ventilator-associated lung injury. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2012, 25: 123-130. 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32834f8c7f

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Andre Benedito da Silva for animal care, Ana Lucia Neves da Silva for help with microscopy, Moira Elizabeth Schottler and Claudia Buchweitz for assistance in editing the manuscript and MAQUET for providing technical support. This study was supported by Centers of Excellence Program (PRONEX-FAPERJ), Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), Rio de Janeiro State Research Supporting Foundation (FAPERJ), São Paulo State Research Supporting Foundation (FAPESP), National Institute of Science and Technology of Drugs and Medicine (INCT-INOFAR), Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Level Personnel (CAPES), and the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (TARKINAID, FP7-2007-2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Dr Gama de Abreu was granted a patent on the variable pressure support ventilation mode of assisted ventilation (noisy PSV), which has been licensed to Dräger Medical AG (Lübeck, Germany). The remaining authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions

FS: animal preparation, performance of experimental work, analysis of the mechanical and histological data, statistical analysis and drafting of the manuscript. LM: animal preparation, performance of experimental work, preliminary analysis of the data and helped draft the manuscript. CLS: animal preparation, performance of experimental work, analysis of the mechanical data, molecular biology analysis and help with drafting of the manuscript. GPO: animal preparation, performance of experimental work and analysis of the mechanical and morphometric data. FFC: animal preparation, performance of experimental work, analysis of the mechanical and morphometric data and help with drafting of the manuscript. MMM: analysis of the molecular biology data and help with drafting of the manuscript. VLC: analysis of the histological data help with drafting of the manuscript. MGA: experimental design, writing of the manuscript and supervision and oversight of the entire project. CSNBG: animal preparation, performance of experimental work, analysis of the mechanical data, design of the experiments and writing of the manuscript. PP: design of the experiments, writing of the manuscript and supervision and oversight of entire project. PRMR: experimental design, supervision of experimental work, statistical analysis, writing of the manuscript and supervision and oversight of the entire project. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Saddy, F., Moraes, L., Santos, C.L. et al. Biphasic positive airway pressure minimizes biological impact on lung tissue in mild acute lung injury independent of etiology. Crit Care 17, R228 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc13051

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc13051