Abstract

Background

Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) is one of the most important enzymes involved in estrogen metabolism and its functional genetic polymorphisms may be associated with breast cancer (BC) risk. Many epidemiological studies have been conducted to explore the association between the COMT Val158Met polymorphism and breast cancer risk. However, the results remain inconclusive. In order to derive a more precise estimation of this relationship, a large meta-analysis was performed in this study.

Methods

Systematic searches of the PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library were performed. Crude odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to estimate the strength of the association.

Results

A total of 56 studies including 34,358 breast cancer cases and 45,429 controls were included. Overall, no significant associations between the COMT Val158Met polymorphism and breast cancer risk were found for LL versus HH, HL versus HH, LL versus HL, recessive model LL versus HL+HH, and dominant model LL+HL versus HH. In subgroup analysis by ethnicity, source of controls, and menopausal status, there was still no significant association detected in any of the genetic models.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis results suggest that the COMT Val158Met polymorphism may not contribute to breast cancer susceptibility.

Virtual slides

The virtual slides(s) for this article can be found here:http://www.diagnosticpathology.diagnomx.eu/vs4806123577708417

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most frequently occurring cancer and cancer-related deaths are highly prevalent worldwide, which has become a major public health challenge[1]. The mechanism of developing breast cancer is still unclear. It has been widely accepted that exposure to circulating estrogen may be important in the development of breast cancer. Since estrogen biosynthesis and metabolism consist of many translation and transcription steps, the genes involved in these processes may contribute to the level of estrogen and thereby influence the susceptibility to breast cancer. Among the genes identified, BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations have been reported to be associated with a dominantly inherited increased risk of the disease. However, they only account for about 5% of breast cancer occurrences[2]. This fact leaves the possibility that low-penetrance genetic factors are likely to explain most of disease cases.

Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) is an important phase II enzyme involved in the conjugation and inactivation of catechol estrogens[3]. COMT is expressed at high levels in a variety of human tissues including liver, kidney, breast, and red blood cells[4]. The COMT gene is located on chromosome 22q11[5]. A G to A transition in the COMT gene results in valine to methionine amino acid change in codon 108/158 in the cytosolic/membrane-bound form of the protein. This amino acid change is believed to result in a 3–4-fold decrease in enzymatic activity[6, 7]. Since the variant form (Met) has been associated with decreased activity of the COMT compared with the wildtype (Val), these two forms are represented as COMT-L allele and COMT-H allele, respectively. It has been hypothesized that the individuals who inherit the low activity COMT-L gene may be at increased risk for breast cancer because of an increased accumulation of the catechol estrogen intermediates[8–11].

The role of COMT Val158Met polymorphism in the development of breast cancer has been investigated in the past decade, with conflicting results. Several studies have previously suggested an association between the COMT Val158Met polymorphism and an increased risk of breast caner[12–14]. However, other studies have failed to confirm such an association[15, 16]. Moreover, two meta-analyses investigating the same hypothesis[17, 18], quite similar in methods and performed almost at the same time, yielded different conclusions. The exact relationship between genetic polymorphisms of COMT Val158Met and susceptibility to breast cancer has not been entirely established. To clarify the effect of COMT Val158Met on the risk of breast cancer, our study undertakes a meta-analysis of all published case–control observational studies.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Electronic databases PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), Embase (http://www.embase.com/) and Cochrane Library (http://www.thecochranelibrary.com/view/0/index.html) were used to search for all genetic association studies evaluating the COMT Val158Met polymorphism and breast cancer risk up to February 2012, the search strategy was based on combinations of “Breast cancer”, “Catechol-O-methyltransferase”, “COMT”, “polymorphism”, and “mutation”. No language or country restrictions were applied. All eligible studies were retrieved, and their bibliographies were checked for other relevant publications. Review articles and bibliographies of other relevant studies identified were searched by hand to find additional eligible studies. When multiple publications reported on the same or overlapping data, we chose the most recent or largest population. When a study reported the results on different subpopulations, we treated it as separate studies in the meta-analysis.

Selection criteria

Studies included in our meta-analysis had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) evaluate the association between COMT Val108/158Met polymorphism and breast cancer risk; (2) case–control design; (3) sufficient data for estimating an odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI); and (4) studies with full text articles. Studies were excluded if one of the following existed: (1) no control population; and (2) duplicate of previous publication.

Data extraction

Information was carefully extracted from all eligible publications by two investigators (Xue Qin and Qiliu Peng) independently according to the inclusion criteria listed above. For conflicting evaluation, an agreement was reached following discussion during a consensus meeting with a third reviewer (Aiping Qin). For each study, the following information were collected: First author’s name, year of publication, country, ethnicity of the studied population, total numbers of cases and controls, breast cancer diagnosis criteria, matching criteria, genotyping method, menopausal status, sources of the control population, quality control of genotyping and P value for control population in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). We did not define any minimum number of patients to include in our meta-analysis.

Statistical analysis

Crude odds ratios (ORs) together with their corresponding 95% CIs were used to assess the strength of association between the COMT Val158Met polymorphism and breast cancer risk. The pooled ORs were performed for co-dominant model (LL vs. HH, HL vs. HH, and LL vs. HL), dominant model (LL+ HL vs. HH), and recessive model (LL vs. HL+HH), respectively. Departure from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium for the control group in each study was assessed using a web-based program (http://ihg2.helmholtz-muenchen.de/cgibin/hw/hwa1.pl). In subgroup analysis, we evaluated the effect of COMT Val108/158Met polymorphism on the susceptibility of BC in different population stratified by ethnicity (Caucasian, Asian, and Mixed/other), menopausal status (Pre-, and Post-) and sources of the control population (HB, PB, and FB).

For each genetic comparison, a chi-square-based Q-statistic test was used to evaluate the between-study heterogeneity of the studies. If P < 0.10, the between-study heterogeneity was considered to be significant, we chose the random-effects model to calculate the OR. Otherwise, when P ≥ 0.10, the between study heterogeneity was not significant, then the fixed effects model was used. We also measured the effect of heterogeneity using a quantitative measure, I2 = 100% × (Q – df)/Q[19]. The I statistic measures the degree of inconsistency in the studies by calculating what percentage of the total variation across studies is due to heterogeneity rather than by chance[20]. Finally, the overall or pooled estimate of risk (OR) was calculated by a random effects model (DerSimonian–Laird) or a fixed effects model (Mantel–Haenszel) according to the presence (P < 0.10 or I2 > 50%) or absence (P ≥ 0.10 and I2 ≤ 50%) of heterogeneity, respectively.

Cumulative meta-analysis was conducted to identify the influence of the first published study on the subsequent publications, and the evolution of the combined estimates over time according to the ascending date of publication. To identify potentially influential studies, sensitivity analysis was also performed by excluding the studies without definite diagnostic criteria, the studies without quality control when genotyping and the studies whose genotype frequencies in control populations exhibited significant deviation from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE), given that the deviation may denote bias. The funnel plots and Egger regression asymmetry test were used to assess publication bias. Egger’s test can detect funnel plot asymmetry by determining whether the intercept deviates significantly from zero in a regression of the standardized effect estimates against their precision. A T test was performed to determine the significance of the asymmetry. An asymmetric plot suggested possible publication bias (P ≥ 0.05 suggests no bias). All analyses were performed using Stata software, version 10.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Study characteristics

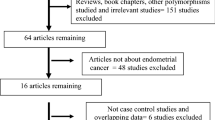

According to our search criteria, 61 studies relevant to the role of COMT Val158Met polymorphism on BC risk were identified. Ten of these articles were excluded: one of these articles was a review[21], four were overlapped subjects[22–25], four did not provide allele or genotyping data[26–29], and one was a study concerned with COMT 1222 G>A polymorphism[30]. Manual search of references cited in the published studies did not reveal any additional articles. As a result, a total of 51 relevant studies met the inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis[9–16, 31–73]. Among them, five of the eligible studies contained data on two different ethnic groups, and we treated them independently[31, 51, 56, 60, 69]. Therefore, a total of 56 separate comparisons consisting of 34,358 BC patients and 45,429 controls were included in our meta-analysis. The characteristics of the 56 case–control comparisons selected for determining the relationship between COMT Val108/158Met polymorphism and risk of BC are summarized in Table 1. These 56 comparisons were consisted of 33 Caucasian samples, 18 Asian populations and 5 mixed/other populations. Thirty of the studies were population-based case–control studies and 20 were hospital-based studies, four of these studies[44, 54, 60, 69] presented COMT Val158Met polymorphism genotype distributions according to family history (familial-based breast cancer). There were 22 comparisons concerned with COMT Val158Met polymorphism and premenopausal BC patients and 27 comparisons concerned with COMT Val158Met polymorphism and postmenopausal BC patients (see Table 1). Seventy-one percent (40/56) studies in the present meta-analysis used the golden criteria of “histologically confirmed” or “pathologically conformed” as BC diagnosis. Eighty-two (46/56) percent of the control populations matched to BC patients with age and 52% (29/56) studies used the classic PCR-RFLP assay to genotype the COMT Val158Met polymorphism, about 52% (29/56) of the case–control studies included mentioned the quality control when genotyping. The genotype frequencies of control group in 3 studies were not consistent with HWE[33, 41, 70]. We could not calculate the P value of HWE in two studies[66, 73] because they only provided data with dominant model. To remove possible HWE stratification, for each analysis involving any of these 5 studies, sensitivity analysis would be carried out by excluding the studies the genotype frequencies for control group of which deviate from HWE and the studies whose P value of HWE in the control group could not be calculated.

Quantitative synthesis of data

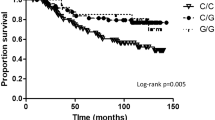

The pooled ORs along with their 95% CIs and the results of the heterogeneity test are presented in detail in Table 2. Overall, no significant associations between COMT Val158Met polymorphism and breast cancer susceptibility were observed in all genetic models when all the eligible studies were pooled into the meta-analysis. No significant associations were found for LL versus HH (OR = 0.999, 95% CI 0.0.925–1.078; I2= 55.0 and P = 0.000 for heterogeneity), HL versus HH (OR = 1.005, 95% CI 0.959–1.052; I2= 27.1 and P = 0.038 for heterogeneity), LL versus HL (OR = 0.983, 95% CI 0.926–1.045; I2= 44.4 and P = 0.000 for heterogeneity), recessive model LL versus HL+HH (OR = 0.988, 95% CI 0.929–1.050; I2= 51.3 and P = 0.000 for heterogeneity) and dominant model LL+HL versus HH (OR = 1.001, 95% CI 0.954–1.051; I2= 41.0 and P = 0.001 for heterogeneity). Next, the effect of COMT Val158Met polymorphism on breast cancer risk was evaluated according to ethnicity, menopausal status (Figure 1; Figure 2) and sources of controls. Similarly, no significant association was found in any of the genetic models. We further conducted a meta-analysis after the five studies[33, 41, 66, 70, 73] whose genotype frequencies significantly deviated from HWE or whose P values of HWE in the control population unable to be calculated were excluded. The results were not materially changed in any genetic models. Sensitivity analysis by excluding the studies without definite diagnostic criteria and the studies without quality control when genotyping did not alter the pattern of the results. Cumulative meta-analysis was performed for dominant model LL +LH versus HH in the overall populations. In the overall populations, the random effects odds ratio was always insignificantly larger or smaller than 1. It changed little from around 0.998 after the year 2007 (Figure 3), indicating the stability of the association.

Cumulative meta-analysis of the association between COMT Val158Met polymorphism and breast cancer susceptibility risk of the overall populations using a random effects model (dominant model LL+HL versus HH) . Each study was used as an information step. The vertical dotted line is the summary odds ratio. Bars, 95% confidence interval (CI).

Publication bias

Begg’s funnel plots and Egger’s tests were performed to assess publication bias. The shapes of the funnel plots revealed no obvious asymmetry (Figure 4). The Egger’s test was then used to statistically assess funnel plot symmetry. The results suggested no evidence of publication bias (t = 0.94 and P = 0.352 for dominant model). The results indicated that the results of these meta-analyses are relatively stable and that publication bias is unlikely to affect the results of the meta-analyses.

Discussion

Estrogens, estrone, and estradiol are catabolized to catechol estrogens. Estrogen metabolites, such as 4-hydroxyestrone and 4-hydroxyestrone, shown to be involved in breast carcinogenesis[74]. Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) catalyzes the O-methylation of these carcinogenic estrogens to methoxyes tradiols and methoxyestrones. In the COMT gene, a G to A transition results in an amino acid change (Val/Met) at codon 108 of soluble COMT and codon 158 of membrane-bound COMT. This amino acid change is believed to result in a 3–4-fold decrease in enzymatic activity[6, 7]. It has been hypothesized that individuals who inherit the low activity COMT gene may be at increased risk for breast cancer because of an increased accumulation of the catechol estrogen intermediates. The potential association between the COMT Val108/158Met polymorphism and the risk of subsequent BC has evoked a huge interest from clinicians, scientists, and the public. During the past few years a large number of studies with case–control design have been carried out to investigate this topic but consistent results have not been reported. We therefore conducted a meta-analysis of the evidence obtained from all published studies in order to elucidate and provide a quantitative reassessment of the association. To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive meta-analysis to date to evaluate the association between COMT Val108/158Met polymorphism and breast cancer risk.

We did not observe a positive relationship between COMT Val108/158Met polymorphism and breast cancer risk either overall or among subgroups of women defined by ethnicity, menopausal status or sources of the control population. In previous studies, overall the findings were inconsistent. Lavigne et al. observed a large increase in the risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal obese women carrying the COMT-LL genotype, and an inverse association among premenopausal women with the relative risk (RR) for COMT-LL stronger among postmenopausal women with high BMI[9]. Thompson et al. reported positive associations for the COMT-HL and COMT-LL genotypes among premenopausal women and found that modification of RRs by BMI was highest among premenopausal women with a high BMI[10]. A comprehensive study of the entire estrogen-metabolizing pathway (CYP17, CYP1A1, COMT) also reported that breast cancer is only associated with the low activity COMT genotype in women with a high BMI and that the COMT-LL genotype was strongly associated with breast cancer risk, with an adjusted OR of as high as 4.02[12]. In contrast to the other studies but in line with the findings of the current study, Lajin et al. did not observe any association between one or two copies of the COMT-L allele and breast cancer risk, and did not find strong modification of RR estimates by menopausal status[72]. In an effort to shed some light on the impact of COMT Val108/158Met polymorphism on breast cancer risk, two previous meta-analyses[17, 18] were conducted almost at the same time to explore the relationship between COMT Val108/158Met polymorphism and breast cancer. Ding et al.[18] examined the effect of COMT Val158Met polymorphism on breast cancer risk by combining results in meta-analysis. They concluded that COMT Val158Met polymorphism was significantly associated with increased breast cancer risk in European population. However, Mao et al.[17] did not find any relationship between COMT Val158Met polymorphism and breast cancer risk in any genetic models including among Caucasian, Asian, premenopausal, and postmenopausal women in their meta-analysis, which was consistent with the findings of our study. The discrepancy in previously reported findings was most probably because that the previous studies with relatively small sample size may have insufficient statistical power to detect the exact effect or may have generated a fluctuated risk estimate. However, in our study, large number of cases and controls were pooled from all published studies, which greatly increased statistical power of the analysis and provided enough evidence for us to draw a safe and reliable conclusion.

Heterogeneity is a potential problem that may affect the interpretation of the results. The present meta-analysis showed that there was large heterogeneity between studies (table 2). Common reasons for heterogeneity may include differences in the studied populations (e.g., ethnicity, menopausal status), or in methods (e.g., genotyping), or in sample selection (e.g., source of control populations), or it may be due to interaction with other risk factors (e.g., BRCA variants). Finding of the source of heterogeneity is one of the most important goals of a meta-analysis. Therefore, we stratified the studies according to ethnicity, source of control subjects of the studies, and menopausal status. Subsequent subgroup analysis stratified by ethnicity, source of control subjects, and menopausal status identified large heterogeneity as well, indicating that menopausal status, ethnicity or source of control subjects contributed little to the existence of overall heterogeneity. Unfortunately, our study had insufficient information for subgroup analysis to detect whether the variants in BRCA gene might be great sources of heterogeneity. We found that in three studies[33, 41, 70] the genotypic frequencies showed significant deviation from the expected frequencies based on Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium and two studies[66, 73] provide insufficient data for calculating P value of HWE in the control populations. Excluding these five studies did not alter the heterogeneity between studies. However, when heterogeneity between the studies exists, the results could be interpreted in the context of cumulative meta-analysis, which provides a measure of how much the genetic effect changes as more data accumulate over time[75]. In our study, the results of cumulative meta-analysis for dominant model LL+HL versus HH showed stability in pooled odds ratio after the year 2007 in the overall populations, which provide evidence for drawing safe conclusion about the insignificant association between COMT Val158Met polymorphism and breast cancer risk.

Some limitations of this meta-analysis should be acknowledged. First, some studies found significant associations between COMT Val108/158Met polymorphism and breast cancer risk in several subgroups of populations, such as associations among postmenopausal women with a low body mass index (BMI)[10, 11], a high BMI[9] or women at young ages[11]. It is difficult for a meta-anlysis to derive such specific associations because the results from previous studies were not presented in a uniform standard. Second, our results were based on unadjusted estimates and a more precise analysis should be carried out if individual data were available, this would allow for adjustment by other covariates including age, BMI, ethnicity, lifestyle, and environmental factors. Third, all of the studies were performed in Asian and Caucasian populations. Further studies are needed in other ethnic populations because of possible ethnic differences of the COMT polymorphisms. In spite of these, our present meta-analysis also had some advantages. First, substantial number of cases and controls were pooled from all publications concerned with COMT Val158Met polymorphism and BC risk, which greatly increased statistical power of the analysis and provided enough evidence for us to draw a safe conclusion. Second, the quality of case–control studies included in this meta-analysis was satisfactory according to our selection criteria. Third, no publication bias was detected in this meta-analysis, which indicated that the pooled results of our study should be reliable.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis suggests that the COMT Val158Met polymorphism may not be associated with breast cancer risk. However, it is necessary to conduct large sample studies using standardized unbiased genotyping methods, homogeneous breast cancer patients, and well-matched controls. Moreover, gene-gene and gene-environment interactions should also be considered in the analysis. Such studies taking these factors into account may eventually lead to a better, more comprehensive understanding of the association between COMT Val158Met polymorphism and BC risk.

Abbreviations

- BC:

-

Breast cancer

- HWE:

-

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COMT:

-

Catechol-O-methyltransferase

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- PB:

-

Population-based

- FB:

-

Family-based

- HB:

-

Hospital-based

- Pre:

-

Premenopausal

- Post:

-

Postmenopausal

- PCR-RFLP PCR:

-

based restriction fragment length polymorphism

- MALDI-TOF MS:

-

matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- LP:

-

Luorescence polarization.

References

Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P: Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005, 55 (2): 74-108. 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74.

Lux MP, Fasching PA, Beckmann MW: Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: review and future perspectives. J Mol Med (Berl). 2006, 84 (1): 16-28. 10.1007/s00109-005-0696-7.

Guldberg HC, Marsden CA: Catechol-O-methyl transferase: pharmacological aspects and physiological role. Pharmacol Rev. 1975, 27 (2): 135-206.

Mannisto PT, Ulmanen I, Lundstrom K, Taskinen J, Tenhunen J, Tilgmann C, Kaakkola S: Characteristics of catechol O-methyl-transferase (COMT) and properties of selective COMT inhibitors. Prog Drug Res. 1992, 39: 291-350.

Grossman MH, Emanuel BS, Budarf ML: Chromosomal mapping of the human catechol-O-methyltransferase gene to 22q11.1----q11.2. Genomics. 1992, 12 (4): 822-825. 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90316-K.

Weinshilboum RM, Raymond FA: Inheritance of low erythrocyte catechol-o-methyltransferase activity in man. Am J Hum Genet. 1977, 29 (2): 125-135.

Dawling S, Roodi N, Mernaugh RL, Wang X, Parl FF: Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT)-mediated metabolism of catechol estrogens: comparison of wild-type and variant COMT isoforms. Cancer Res. 2001, 61 (18): 6716-6722.

Goodman JE, Jensen LT, He P, Yager JD: Characterization of human soluble high and low activity catechol-O-methyltransferase catalyzed catechol estrogen methylation. Pharmacogenetics. 2002, 12 (7): 517-528. 10.1097/00008571-200210000-00003.

Lavigne JA, Helzlsouer KJ, Huang HY, Strickland PT, Bell DA, Selmin O, Watson MA, Hoffman S, Comstock GW, Yager JD: An association between the allele coding for a low activity variant of catechol-O-methyltransferase and the risk for breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1997, 57 (24): 5493-5497.

Thompson PA, Shields PG, Freudenheim JL, Stone A, Vena JE, Marshall JR, Graham S, Laughlin R, Nemoto T, Kadlubar FF, Ambrosone CB: Genetic polymorphisms in catechol-O-methyltransferase, menopausal status, and breast cancer risk. Cancer Res. 1998, 58 (10): 2107-2110.

Mitrunen K, Jourenkova N, Kataja V, Eskelinen M, Kosma VM, Benhamou S, Kang D, Vainio H, Uusitupa M, Hirvonen A: Polymorphic catechol-O-methyltransferase gene and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001, 10 (6): 635-640.

Huang CS, Chern HD, Chang KJ, Cheng CW, Hsu SM, Shen CY: Breast cancer risk associated with genotype polymorphism of the estrogen-metabolizing genes CYP17, CYP1A1, and COMT: a multigenic study on cancer susceptibility. Cancer Res. 1999, 59 (19): 4870-4875.

Wang Q, Li H, Tao P, Wang YP, Yuan P, Yang CX, Li JY, Yang F, Lee H, Huang Y: Soy isoflavones, CYP1A1, CYP1B1, and COMT polymorphisms, and breast cancer: a case–control study in southwestern China. DNA and cell biology. 2011, 30 (8): 585-595. 10.1089/dna.2010.1195.

Naushad SM, Pavani A, Rupasree Y, Sripurna D, Gottumukkala SR, Digumarti RR, Kutala VK: Modulatory effect of plasma folate and polymorphisms in one-carbon metabolism on catecholamine methyltransferase (COMT) H108L associated oxidative DNA damage and breast cancer risk. Indian journal of biochemistry & biophysics. 2011, 48 (4): 283-289.

Cribb AE, Joy Knight M, Guernsey J, Dryer D, Hender K, Shawwa A, Tesch M, Saleh TM: CYP17, catechol-o-methyltransferase, and glutathione transferase M1 genetic polymorphisms, lifestyle factors, and breast cancer risk in women on Prince Edward Island. The breast journal. 2011, 17 (1): 24-31. 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2010.01025.x.

Cerne JZ, Pohar-Perme M, Novakovic S, Frkovic-Grazio S, Stegel V, Gersak K: Combined effect of CYP1B1, COMT, GSTP1, and MnSOD genotypes and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. Journal of gynecologic oncology. 2011, 22 (2): 110-119. 10.3802/jgo.2011.22.2.110.

Mao C, Wang XW, Qiu LX, Liao RY, Ding H, Chen Q: Lack of association between catechol-O-methyltransferase Val108/158Met polymorphism and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 25,627 cases and 34,222 controls. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010, 121 (3): 719-725. 10.1007/s10549-009-0650-4.

Ding H, Fu Y, Chen W, Wang Z: COMT Val158Met polymorphism and breast cancer risk: evidence from 26 case–control studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010, 123 (1): 265-270. 10.1007/s10549-010-0759-5.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG: Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002, 21 (11): 1539-1558. 10.1002/sim.1186.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG: Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003, 327 (7414): 557-560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

Kang D: Genetic polymorphisms and cancer susceptibility of breast cancer in Korean women. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2003, 36 (1): 28-34. 10.5483/BMBRep.2003.36.1.028.

Naushad SM, Reddy CA, Rupasree Y, Pavani A, Digumarti RR, Gottumukkala SR, Kuppusamy P, Kutala VK: Cross-talk between one-carbon metabolism and xenobiotic metabolism: implications on oxidative DNA damage and susceptibility to breast cancer. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2011, 61 (3): 715-723. 10.1007/s12013-011-9245-x.

Song CG, Hu Z, Yuan WT, Di GH, Shen ZZ, Huang W, Shao ZM: Prevalence of Val158Met polymorphism in COMT gene on non-BRCA1/2 hereditary breast cancer. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2006, 44 (19): 1310-1313.

Wang Q, Wang YP, Li JY, Yuan P, Yang F, Li H: Polymorphic catechol-O-methyltransferase gene, soy isoflavone intake and breast cancer in postmenopausal women: a case–control study. Chin J Cancer. 2010, 29 (7): 683-688. 10.5732/cjc.009.10700.

Park SK, Yim DS, Yoon KS, Choi IM, Choi JY, Yoo KY, Noh DY, Choe KJ, Ahn SH, Hirvonen A, Kang D: Combined effect of GSTM1, GSTT1, and COMT genotypes in individual breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004, 88 (1): 55-62. 10.1007/s10549-004-0745-x.

Ji Y, Olson J, Zhang J, Hildebrandt M, Wang L, Ingle J, Fredericksen Z, Sellers T, Miller W, Dixon JM, Brauch H, Eichelbaum M, Justenhoven C, Hamann U, Ko Y, Bruning T, Chang-Claude J, Wang-Gohrke S, Schaid D, Weinshilboum R: Breast cancer risk reduction and membrane-bound catechol O-methyltransferase genetic polymorphisms. Cancer Res. 2008, 68 (14): 5997-6005. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0043.

Crooke PS, Ritchie MD, Hachey DL, Dawling S, Roodi N, Parl FF: Estrogens, enzyme variants, and breast cancer: a risk model. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006, 15 (9): 1620-1629. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0198.

Silva SN, Cabral MN, Bezerra de Castro G, Pires M, Azevedo AP, Manita I, Pina JE, Rueff J, Gaspar J: Breast cancer risk and polymorphisms in genes involved in metabolism of estrogens (CYP17, HSD17beta1, COMT and MnSOD): possible protective role of MnSOD gene polymorphism Val/Ala and Ala/Ala in women that never breast fed. Oncol Rep. 2006, 16 (4): 781-788.

Corder EH, Hefler LA: Multilocus genotypes spanning estrogen metabolism associated with breast cancer and fibroadenoma. Rejuvenation Res. 2006, 9 (1): 56-60. 10.1089/rej.2006.9.56.

Jakubowska A, Gronwald J, Menkiszak J, Gorski B, Huzarski T, Byrski T, Toloczko-Grabarek A, Gilbert M, Edler L, Zapatka M, Eils R, Lubinski J, Scott RJ, Hamann U: BRCA1-associated breast and ovarian cancer risks in Poland: no association with commonly studied polymorphisms. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010, 119 (1): 201-211. 10.1007/s10549-009-0390-5.

Millikan RC, Pittman GS, Tse CK, Duell E, Newman B, Savitz D, Moorman PG, Boissy RJ, Bell DA: Catechol-O-methyltransferase and breast cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 1998, 19 (11): 1943-1947. 10.1093/carcin/19.11.1943.

Goodman JE, Lavigne JA, Wu K, Helzlsouer KJ, Strickland PT, Selhub J, Yager JD: COMT genotype, micronutrients in the folate metabolic pathway and breast cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2001, 22 (10): 1661-1665. 10.1093/carcin/22.10.1661.

Yim DS, Parkb SK, Yoo KY, Yoon KS, Chung HH, Kang HL, Ahn SH, Noh DY, Choe KJ, Jang IJ, Shin SG, Strickland PT, Hirvonen A, Kang D: Relationship between the Val158Met polymorphism of catechol O-methyl transferase and breast cancer. Pharmacogenetics. 2001, 11 (4): 279-286. 10.1097/00008571-200106000-00001.

Bergman-Jungestrom M, Wingren S: Catechol-O-Methyltransferase (COMT) gene polymorphism and breast cancer risk in young women. British journal of cancer. 2001, 85 (6): 859-862. 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2009.

Hamajima N, Matsuo K, Tajima K, Mizutani M, Iwata H, Iwase T, Miura S, Oya H, Obata Y: Limited association between a catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) polymorphism and breast cancer risk in Japan. International journal of clinical oncology / Japan Society of Clinical Oncology. 2001, 6 (1): 13-18. 10.1007/PL00012073.

Kocabas NA, Sardas S, Cholerton S, Daly AK, Karakaya AE: Cytochrome P450 CYP1B1 and catechol O-methyltransferase (COMT) genetic polymorphisms and breast cancer susceptibility in a Turkish population. Archives of toxicology. 2002, 76 (11): 643-649. 10.1007/s00204-002-0387-x.

Comings DE, Gade-Andavolu R, Cone LA, Muhleman D, MacMurray JP: A multigene test for the risk of sporadic breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2003, 97 (9): 2160-2170. 10.1002/cncr.11340.

Wedren S, Rudqvist TR, Granath F, Weiderpass E, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Persson I, Magnusson C: Catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphism and post-menopausal breast cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2003, 24 (4): 681-687. 10.1093/carcin/bgg022.

Wu AH, Tseng CC, Van Den Berg D, Yu MC: Tea intake, COMT genotype, and breast cancer in Asian-American women. Cancer Res. 2003, 63 (21): 7526-7529.

Tan W, Qi J, Xing DY, Miao XP, Pan KF, Zhang L, Lin DX: [Relation between single nucleotide polymorphism in estrogen-metabolizing genes COMT, CYP17 and breast cancer risk among Chinese women]. Zhonghua zhong liu za zhi [Chinese journal of oncology]. 2003, 25 (5): 453-456.

Sazci A, Ergul E, Utkan NZ, Canturk NZ, Kaya G: Catechol-O-methyltransferase Val 108/158 Met polymorphism in premenopausal breast cancer patients. Toxicology. 2004, 204 (2–3): 197-202.

Dunning AM, Dowsett M, Healey CS, Tee L, Luben RN, Folkerd E, Novik KL, Kelemen L, Ogata S, Pharoah PD, Easton DF, Day NE, Ponder BA: Polymorphisms associated with circulating sex hormone levels in postmenopausal women. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2004, 96 (12): 936-945. 10.1093/jnci/djh167.

Hefler LA, Tempfer CB, Grimm C, Lebrecht A, Ulbrich E, Heinze G, Leodolter S, Schneeberger C, Mueller MW, Muendlein A, Koelbl H: Estrogen-metabolizing gene polymorphisms in the assessment of breast carcinoma risk and fibroadenoma risk in Caucasian women. Cancer. 2004, 101 (2): 264-269. 10.1002/cncr.20361.

Ahsan H, Chen Y, Whittemore AS, Kibriya MG, Gurvich I, Senie RT, Santella RM: A family-based genetic association study of variants in estrogen-metabolism genes COMT and CYP1B1 and breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004, 85 (2): 121-131. 10.1023/B:BREA.0000025401.60794.68.

Modugno F, Zmuda JM, Potter D, Cai C, Ziv E, Cummings SR, Stone KL, Morin PA, Greene D, Cauley JA: Estrogen metabolizing polymorphisms and breast cancer risk among older white women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005, 93 (3): 261-270. 10.1007/s10549-005-5347-8.

Lin SC, Chou YC, Wu MH, Wu CC, Lin WY, Yu CP, Yu JC, You SL, Chen CJ, Sun CA: Genetic variants of myeloperoxidase and catechol-O-methyltransferase and breast cancer risk. European journal of cancer prevention: the official journal of the European Cancer Prevention Organisation (ECP). 2005, 14 (3): 257-261. 10.1097/00008469-200506000-00010.

Lin WY, Chou YC, Wu MH, Jeng YL, Huang HB, You SL, Chu TY, Chen CJ, Sun CA: Polymorphic catechol-O-methyltransferase gene, duration of estrogen exposure, and breast cancer risk: a nested case–control study in Taiwan. Cancer detection and prevention. 2005, 29 (5): 427-432. 10.1016/j.cdp.2005.07.003.

Le Marchand L, Donlon T, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Wilkens LR: Estrogen metabolism-related genes and breast cancer risk: the multiethnic cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14 (8): 1998-2003. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0076.

Wen W, Cai Q, Shu XO, Cheng JR, Parl F, Pierce L, Gao YT, Zheng W: Cytochrome P450 1B1 and catechol-O-methyltransferase genetic polymorphisms and breast cancer risk in Chinese women: results from the shanghai breast cancer study and a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14 (2): 329-335. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0392.

Cheng TC, Chen ST, Huang CS, Fu YP, Yu JC, Cheng CW, Wu PE, Shen CY: Breast cancer risk associated with genotype polymorphism of the catechol estrogen-metabolizing genes: a multigenic study on cancer susceptibility. International journal of cancer. 2005, 113 (3): 345-353. 10.1002/ijc.20630.

Gaudet MM, Bensen JT, Schroeder J, Olshan AF, Terry MB, Eng SM, Teitelbaum SL, Britton JA, Lehman TA, Neugut AI, Ambrosone CB, Santella RM, Gammon MD: Catechol-O-methyltransferase haplotypes and breast cancer among women on Long Island, New York. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006, 99 (2): 235-240. 10.1007/s10549-006-9205-0.

Gallicchio L, Berndt SI, McSorley MA, Newschaffer CJ, Thuita LW, Argani P, Hoffman SC, Helzlsouer KJ: Polymorphisms in estrogen-metabolizing and estrogen receptor genes and the risk of developing breast cancer among a cohort of women with benign breast disease. BMC cancer. 2006, 6: 173-10.1186/1471-2407-6-173.

Chang TW, Wang SM, Guo YL, Tsai PC, Huang CJ, Huang W: Glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms associated with risk of breast cancer in southern Taiwan. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2006, 15 (6): 754-761. 10.1016/j.breast.2006.03.008.

Onay VU, Briollais L, Knight JA, Shi E, Wang Y, Wells S, Li H, Rajendram I, Andrulis IL, Ozcelik H: SNP-SNP interactions in breast cancer susceptibility. BMC cancer. 2006, 6: 114-10.1186/1471-2407-6-114.

Pharoah PD, Tyrer J, Dunning AM, Easton DF, Ponder BA: Association between common variation in 120 candidate genes and breast cancer risk. PLoS genetics. 2007, 3 (3): e42-10.1371/journal.pgen.0030042.

Ralph DA, Zhao LP, Aston CE, Manjeshwar S, Pugh TW, DeFreese DC, Gramling BA, Shimasaki CD, Jupe ER: Age-specific association of steroid hormone pathway gene polymorphisms with breast cancer risk. Cancer. 2007, 109 (10): 1940-1948. 10.1002/cncr.22634.

Akisik E, Dalay N: Functional polymorphism of thymidylate synthase, but not of the COMT and IL-1B genes, is associated with breast cancer. Journal of clinical laboratory analysis. 2007, 21 (2): 97-102. 10.1002/jcla.20139.

Hu Z, Song CG, Lu JS, Luo JM, Shen ZZ, Huang W, Shao ZM: A multigenic study on breast cancer risk associated with genetic polymorphisms of ER Alpha, COMT and CYP19 gene in BRCA1/BRCA2 negative Shanghai women with early onset breast cancer or affected relatives. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2007, 133 (12): 969-978. 10.1007/s00432-007-0244-7.

Takata Y, Maskarinec G, Le Marchand L: Breast density and polymorphisms in genes coding for CYP1A2 and COMT: the Multiethnic Cohort. BMC cancer. 2007, 7: 30-10.1186/1471-2407-7-30.

Onay UV, Aaltonen K, Briollais L, Knight JA, Pabalan N, Kilpivaara O, Andrulis IL, Blomqvist C, Nevanlinna H, Ozcelik H: Combined effect of CCND1 and COMT polymorphisms and increased breast cancer risk. BMC cancer. 2008, 8: 6-10.1186/1471-2407-8-6.

Justenhoven C, Hamann U, Schubert F, Zapatka M, Pierl CB, Rabstein S, Selinski S, Mueller T, Ickstadt K, Gilbert M, Ko YD, Baisch C, Pesch B, Harth V, Bolt HM, Vollmert C, Illig T, Eils R, Dippon J, Brauch H: Breast cancer: a candidate gene approach across the estrogen metabolic pathway. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008, 108 (1): 137-149. 10.1007/s10549-007-9586-8.

He C, Tamimi RM, Hankinson SE, Hunter DJ, Han J: A prospective study of genetic polymorphism in MPO, antioxidant status, and breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009, 113 (3): 585-594. 10.1007/s10549-008-9962-z.

Reding KW, Weiss NS, Chen C, Li CI, Carlson CS, Wilkerson HW, Farin FM, Thummel KE, Daling JR, Malone KE: Genetic polymorphisms in the catechol estrogen metabolism pathway and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009, 18 (5): 1461-1467. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0917.

MARIE-GENICA Consortium on Genetic Susceptibility for Menopausal Hormone Therapy Related Breast Cancer Risk: Genetic polymorphisms in phase I and phase II enzymes and breast cancer risk associated with menopausal hormone therapy in postmenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010, 119 (2): 463-474.

Yadav S, Singhal NK, Singh V, Rastogi N, Srivastava PK, Singh MP: Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms in CYP1B1 and COMT genes with breast cancer susceptibility in Indian women. Disease markers. 2009, 27 (5): 203-210.

Shrubsole MJ, Lu W, Chen Z, Shu XO, Zheng Y, Dai Q, Cai Q, Gu K, Ruan ZX, Gao YT, Zheng W: Drinking green tea modestly reduces breast cancer risk. The Journal of nutrition. 2009, 139 (2): 310-316.

Sangrajrang S, Sato Y, Sakamoto H, Ohnami S, Laird NM, Khuhaprema T, Brennan P, Boffetta P, Yoshida T: Genetic polymorphisms of estrogen metabolizing enzyme and breast cancer risk in Thai women. International journal of cancer. 2009, 125 (4): 837-843. 10.1002/ijc.24434.

Moreno-Galvan M, Herrera-Gonzalez NE, Robles-Perez V, Velasco-Rodriguez JC, Tapia-Conyer R, Sarti E: Impact of CYP1A1 and COMT genotypes on breast cancer risk in Mexican women: a pilot study. The International journal of biological markers. 2010, 25 (3): 157-163.

Syamala VS, Syamala V, Sheeja VR, Kuttan R, Balakrishnan R, Ankathil R: Possible risk modification by polymorphisms of estrogen metabolizing genes in familial breast cancer susceptibility in an Indian population. Cancer investigation. 2010, 28 (3): 304-311. 10.3109/07357900902744494.

Peterson NB, Trentham-Dietz A, Garcia-Closas M, Newcomb PA, Titus-Ernstoff L, Huang Y, Chanock SJ, Haines JL, Egan KM: Association of COMT haplotypes and breast cancer risk in caucasian women. Anticancer research. 2010, 30 (1): 217-220.

Delort L, Satih S, Kwiatkowski F, Bignon YJ, Bernard-Gallon DJ: Evaluation of breast cancer risk in a multigenic model including low penetrance genes involved in xenobiotic and estrogen metabolisms. Nutrition and cancer. 2010, 62 (2): 243-251. 10.1080/01635580903305300.

Lajin B, Hamzeh AR, Ghabreau L, Mohamed A, Al Moustafa AE, Alachkar A: Catechol-O-methyltransferase Val 108/158 Met polymorphism and breast cancer risk: a case control study in Syria. Breast cancer (Tokyo, Japan). 2011, Epub ahead of print

dos Santos RA, Teixeira AC, Mayorano MB, Carrara HH, de Andrade J, Takahashi CS: Variability in estrogen-metabolizing genes and their association with genomic instability in untreated breast cancer patients and healthy women. Journal of biomedicine & biotechnology. 2011, 2011: 571784-

Zhu BT, Conney AH: Functional role of estrogen metabolism in target cells: review and perspectives. Carcinogenesis. 1998, 19 (1): 1-27. 10.1093/carcin/19.1.1.

Lau J, Antman EM, Jimenez-Silva J, Kupelnick B, Mosteller F, Chalmers TC: Cumulative meta-analysis of therapeutic trials for myocardial infarction. The New England journal of medicine. 1992, 327 (4): 248-254. 10.1056/NEJM199207233270406.

Acknowledgements

This work was not supported by any kind of fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest in relation to this study.

Authors’ contributions

All authors have read and approved the final files for this manuscript.

Xue Qin, Qiliu Peng, Aiping Qin, Zhiping Chen contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, X., Peng, Q., Qin, A. et al. Association of COMT Val158Met polymorphism and breast cancer risk: an updated meta-analysis. Diagn Pathol 7, 136 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-7-136

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-7-136