Abstract

Background

Candida can cause mucocutaneous and/or systemic infections in hospitalized and immunosuppressed patients. Most individuals are colonized by Candida spp. as part of the oral flora and the intestinal tract. We compared oral and systemic isolates for the capacity to form biofilm in an in vitro biofilm model and pathogenicity in the Galleria mellonella infection model. The oral Candida strains were isolated from the HIV patients and included species of C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. krusei, C. norvegensis, and C. dubliniensis. The systemic strains were isolated from patients with invasive candidiasis and included species of C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. lusitaniae, and C. kefyr. For each of the acquired strains, biofilm formation was evaluated on standardized samples of silicone pads and acrylic resin. We assessed the pathogenicity of the strains by infecting G. mellonella animals with Candida strains and observing survival.

Results

The biofilm formation and pathogenicity in Galleria was similar between oral and systemic isolates. The quantity of biofilm formed and the virulence in G. mellonella were different for each of the species studied. On silicone pads, C. albicans and C. dubliniensis produced more biofilm (1.12 to 6.61 mg) than the other species (0.25 to 3.66 mg). However, all Candida species produced a similar biofilm on acrylic resin, material used in dental prostheses. C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis were the most virulent species in G. mellonella with 100% of mortality, followed by C. lusitaniae (87%), C. novergensis (37%), C. krusei (25%), C. glabrata (20%), and C. kefyr (12%).

Conclusions

We found that on silicone pads as well as in the Galleria model, biofilm formation and virulence depends on the Candida species. Importantly, for C. albicans the pathogenicity of oral Candida isolates was similar to systemic Candida isolates, suggesting that Candida isolates have similar biofilm-forming ability and virulence regardless of the infection site from which it was isolated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Fungi are increasingly recognized as major pathogens in critically ill patients. Candida spp. are the fourth leading cause of bloodstream infections in the U.S. and disseminated candidiasis is associated with a mortality in excess of 25% [1–3]. Oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC) is the most frequent opportunistic infection encountered in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected individuals with 90% at some point experiencing OPC during the course of HIV disease [4]. Among Candida species, C. albicans is the most commonly isolated and responsible for the majority of superficial and systemic infections. However, many non-albicans species, such as C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis and C. tropicalis have recently emerged as important pathogens in suitably debilitated individuals [5].

A major virulence factor of Candida is its ability to adapt to a variety of different habitats and the consequent formation of surface-attached microbial communities known as biofilms [5]. Candida biofilms can develop on natural host surfaces or on biomaterials used in medical devices such as silicone and in dental prosthesis such as acrylic resin [6, 7]. The biofilm formation in vitro entails three basic stages: (i) attachment and colonization of yeast cells to a surface, (ii) growth and proliferation of yeast cells to allow formation of a basal layer of anchoring cells, and (iii) growth of pseudohyphae and extensive hyphae concomitant with the production of extracellular matrix material [8, 9]. Once established, Candida biofilms serve as a persistent reservoir of infection and are more resistant to antifungal agents [6].

The versatility of fungal pathogenicity mechanisms and their development of resistance to antifungal drugs indicate the importance of understanding the nature of host-pathogen interactions. Researchers have developed invertebrate model hosts in order to facilitate the study of evolutionarily preserved elements of fungal virulence and host immunity [10]. These invertebrate systems such as Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, Dictyostelium discoideum and Galleria mellonella offer a number of advantages over mammalian vertebrate models, predominantly because they allow the study of strains without the ethical considerations associated with mammalian studies [11–13]. Importantly, Candida pathogenicity can be evaluated using the greater wax moth G. mellonella as an infection model. This model has yielded results that are comparable to those obtained using mammalian models and there is remarkable commonality between virulence factors required for disease in mice and for killing of G. mellonella [14–17].

The pathogenesis of Candida spp. depends upon the coordinated expression of multiple genes in a manner that facilitates proliferation, invasion and tissue damage in a host. Since each invaded tissue is a unique ecological niche that changes over the course of the disease process, the expression of genes by Candida can vary according the infected site [18]. Costa et al. [19] demonstrated that blood Candida isolates were more proteolytic than oral cavity isolates while oral cavity isolates produced more phospholipase than blood isolates. On the other hand, Hasan et al. [20] using colorimetric assays verified that C. albicans strains isolated both from blood and oral mucosa produced the same quantity of biofilm. However, there are no studies to interrogate biofilm production on medical biomaterials and pathogenicity of isolates from localized and systemic candidiasis using an invertebrate model.

The objective of this study was to compare biofilm production of oral and systemic Candida isolates using an in vitro biofilm model on silicone (a material that is used in a number of implantable devices and catheters) and acrylic resin (a material that is used in preparation of dental prostheses). We were also interested in determining the pathogenicity of the strains in the Galleria mellonella infection model, considering they were isolated from different host environments, either blood or oral collection sites.

Methods

Candida isolates

A total of 33 clinical Candida strains recovered from oral and systemic candidiasis of different patients were used in this study. The oral Candida strains were isolated from the saliva or oropharyngeal candidiasis of 17 HIV-positive patients (65% men, 35% women) at the Emílio Ribas Institute of Infectious Diseases (São Paulo, SP, Brazil). The mean age was 46 years (33 - 63 years) and CD4+ lymphocyte counts ranged from 105 to 1000 cells/mm3 with a mean count of 388 cells/mm3. Candida spp. isolated from these patients included: C. albicans (n = 11), C. glabrata (n = 3), C. tropicalis (n = 2), C. parapsilosis (n = 1), C. krusei (n = 1), C. norvegensis (n = 1), and C. dubliniensis (n = 2). The Ethics Committee of the Emílio Ribas Institute of Infectious Diseases approved this study (275/2009).

The systemic Candida strains were isolated from patients with invasive candidiasis at Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA, USA) and included species of C. albicans (n = 5), C. glabrata (n = 2), C. tropicalis (n = 2), C. parapsilosis (n = 1), C. kefyr (n = 1), and C. lusitaniae (n = 1) (Table 1). These isolates were collected from eleven patients with a mean age of 57 years (40-78), that were HIV negative but had other underlying medical conditions. The use of Candida isolates was approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Review Board (2008-P-001017).

The identification of Candida species was done by growth on Hicrome Candida (Himedia, Munbai, India), germ tube test, clamydospore formation on corn meal agar, and API20C for sugar assimilation (BioMerieux, Marcy Etoile, France). The identity of C. dubliniensis was determined by a multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) procedure, according to the methodology described by MähB et al. [21].

Susceptibility patterns of the isolates to fluconazole and amphotericin B were determined by the broth microdilution assay according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) document M27-A2 [22]. Final concentrations of fluconazole ranged from 64 to 0.125 μg/mL and amphotericin B from 16 to 0.031 μg/mL. Antifungal activity was expressed as the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of each isolate to the drug. The resistance breakpoints were used as described in the CLSI guidelines [22].

In vitro biofilm model

The ability of Candida isolates to form biofilm on silicone and acrylic resin was evaluated as described by Nobile & Mitchell [23] and Breger et al. [24]. In brief, strains of Candida were grown in YPD medium (2% dextrose, 2% Bacto Peptone, 1% yeast extract) overnight at 30°C, diluted to an OD600 of 0.5 in 2 mL Spider medium, and added to a well of a sterile 12-well plate containing a silicone square measuring 1.5. × 1.5 cm (cut from Cardiovascular Instrument silicone sheets) or a chemically activated acrylic resin measuring 5 mm in diameter and 2.5 mm in thickness (Clássico, São Paulo, SP, Brazil) that had been pretreated overnight with bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich). The inoculated 12-well plate was incubated with gentle agitation (150 rpm) for 90 min at 37°C for adhesion to occur. The standardized samples were washed with 2 mL PBS, and incubation was continued for 60 h at 37°C at 150 rpm in 2 mL of fresh Spider medium.

The platform and attached biofilm were removed from the wells, dried overnight, and weighed the following day. The total biomass (mg) of each biofilm was calculated by subtracting the weight of the platform material prior to biofilm growth from the weight after the drying period and adjusting for the weight of a control pad exposed to no cells.

The average total biomass for each strain was calculated from four independent samples. Statistical significance among the Candida species was determined by the analyses of variance (ANOVA) and the Tukey test using the Minitab Program. For comparison between oral and systemic Candida isolates, the Student t test was used. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Galleria mellonella infection model

G. mellonella were infected with Candida as previously described by Cotter et al. [25], Brennan et al. [26] and Fuchs et al. [27]. In brief, G. mellonella caterpillars in the final instar larval stage (Vanderhorst, Inc., St. Marys, Ohio) were stored in the dark and used within 7 days from the date of shipment. Sixteen randomly chosen caterpillars (330 ± 25 mg) were infected for each Candida isolate.

Candida inocula were prepared by growing 50 mL YPD cultures overnight at 30°C. Cells were pelleted at 1,308 Xg for 10 min followed by three washes in PBS. Cell densities were determined by hemacytometer count. Candida inocula were confirmed by determining the colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL) on YPD.

A Hamilton syringe was used to deliver Candida inocula at 105 cells/larvae in a 10 μL volume into the hemocoel of each larva via the last left proleg. Before injection, the area was cleaned using an alcohol swab. After injection, larvae were incubated in plastic containers (37°C), and the number of dead G. mellonella was scored daily. Larvae were considered dead when they displayed no movement in response to touch. Killing curves were plotted and statistical analysis was performed by the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test using Graph Pad Prism statistical software.

Results

Antifungal susceptibility of oral and systemic Candida isolates

The data of Candida strains identification and susceptibility to antifungal drugs (MIC) are shown in Table 1. The range of MIC to fluconazole was 0.125 to 64 μg/mL both for oral and systemic isolates. The resistance to fluconazole was observed in 5 (23%) oral isolates (4 C. albicans and 1 C. krusei) and 1 (8%) systemic isolate of C. tropicalis. The MIC to amphotericin B ranged from 0.25 to 2 μg/mL for oral isolates and from 0.25 to 1 μg/mL for systemic isolates.

Biofilm formation by oral and systemic Candida isolates

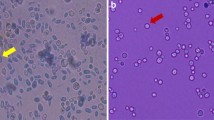

All isolates of oral and systemic candidiasis formed biofilm on silicone pads, but the quantity of biofilm mass was different for the species studied ranging from 2.17 to 6.61 mg. Biofilm formation was highest in C. albicans and C. dubliniensis followed by C. tropicalis and C. norvegensis. Biofilm mass formed by C. albicans differed significantly from biofilm mass produced by C. norvegensis (P = 0.009), C. parapsilosis (P = 0.003), C. glabrata (P = 0.001), C. krusei (P = 0.001), C. lusitaniae (P = 0.001) , and C. kefyr (P = 0.001). Biofilm produced by C. dubliniensis was significantly different from biofilm mass produced by C. parapsilosis (P = 0.046), C. glabrata (P = 0.025), C. krusei (P = 0.013), C. lusitaniae (P = 0.007) , and C. kefyr (P = 0.006) (Table 2 and Figure 1).

The biofilm mass adhered on acrylic resin ranged from 0.25 to 1.50 mg depending on the Candida species tested. C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata, and C. lusitaniae formed more biofilm than C. norvegensis, C. krusei and C. kefyr. However, significant differences between the Candida species were not observed (P = 0.062) (Table 2 and Figure 1).

The biofilm mass formed by oral and systemic isolates of C. albicans were compared and showed similar results both for biofilm formed on silicone pads as biofilm formed on acrylic resin (Figure 2).

Killing of G. mellonella by oral and systemic Candida isolates

The virulence of Candida isolates in the G. mellonella model was dependent on the species studied. C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis were the most virulent species in G. mellonella (Table 1). Among all Candida strains studied, G. mellonella showed mortality rates of 100% after injection with C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis, 87% with C. lusitaniae, 37% with C. novergensis, 25% with C. krusei, 20% with C. glabrata, and 12% with C. kefyr over a 96 hour period (Figures 3 and 4). Of note is that, all isolates of C. albicans, including strains sensitive and resistant to fluconazole, presented the same virulence in G. mellonella with a medium time to mortality of 18 to 24 hours (Table 1).

Killing of G. mellonella larvae by oral (blue lines) and systemic (red lines) isolates of Candida. Comparison of killing curves by Log-rank test: a) strains of C. albicans (P = 0.372); b) strains of C. tropicalis (P = 0.914); c) strains of C. parapsilosis (P = 0.661); d) strains of C. glabrata (P = 0.006). Injections with PBS were used as a control group.

The virulence between oral and systemic Candida isolates was compared according to each species of Candida. The results of survival of G. mellonella larvae showed no statistically significant difference between oral and systemic isolates of C. albicans (P = 0.372, Figure 3a), C. tropicalis (P = 0.914, Figure 3b), and C. parapsilosis (P = 0.661, Figure 3c).

For C. glabrata, a statistically significant difference was observed between the strains CGL002 and CGL003 (P = 0.003), CGL002 and 45 (P = 0.007), CGL003 and 12S (P = 0.049), CGL003 and 55 (P = 0.024), 45 and 55 (P = 0.033), showing the occurrence of variation in virulence between strains of C. glabrata for both the oral isolates and the systemic isolates (Figure 3d).

Discussion

In this study we compared the pathogenicity of oral and systemic Candida isolates. The pathogenesis of diverse candidal diseases depends upon both generalized virulence factors and those that function in specific environments dictated by immune function, tissue site and other host factors. The data presented here demonstrate that the pathogenicity of oral Candida isolates is similar to systemic Candida isolates, suggesting that the pathogenicity of Candida is not correlated with the infected site.

The pathogenesis of both oral and systemic candidiasis is closely dictated by properties of the yeast biofilms [28, 29]. Implanted devices, such as venous catheters or dental prosthesis, are a serious risk factor for Candida infections. They are substrates for the formation of biofilm, which in turn serve as reservoirs of cells to continually seed an infection [8]. It has been estimated that at least 65% of all human infectious are related to microbial biofilms [30, 31].

A variety of methods have recently been used for the quantification of Candida biofilm on different substrata. These include counting of colony forming units (CFU), dry-weight assays, spectrophotometric analysis, and colorimetric assays, such as 2,3-bis (2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino) carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium hydroxide (XTT) reduction assay. However, each method carries its own advantages and limitations [7, 32, 33]. In our study, we used a dry-weight assay because this method allows the single quantification of a Candida biofilm on a clinically relevant substrate such as silicone and acrylic resin. Silicone is frequently used in the manufacture of medical devices and catheters and it is related to development of systemic candidiasis in hospitalized patients. Acrylic resin (methyl methacrylate) is a material widely used in preparation of dental prosthesis and it has significance for development of oral candidiasis.

Among all isolates tested in this study, the quantity of biofilm mass varied according to the Candida species. C. albicans and C. dubliniensis were the highest biofilm producers on silicone pads, followed by C. tropicalis, C. norvegensis, C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata, C. krusei, C. lusitaniae, and C. kefyr. Most studies have shown that the biofilm formation by clinical isolates of Candida was species dependent and generally the highest levels of biofilm formation were observed in C. albicans and the lowest in C. glabrata [5, 20]. Notably, unlike C. albicans and other Candida species, C. glabrata is unable to generate filamentous forms which may contribute to the impared ability of C. glabrata to form a biofilm [5]. The observations for higher quantities of biofilm production by C. albicans and lower biofilm production from the non filamenting C. glabrata, given the same standards of in vitro test conditions, remained true for the clinical isolates from our study. Indeed, for both strains collected orally or systemically, there was very little in the way of quantity or quality of biofilm production for C. glabrata. C. albicans produced the greatest quantity of biofilm regardless of the adhesion platform material or whether it was isolated from oral or invasive infection sites.

Interestingly, the differences in biofilm formation among Candida species on acrylic resin were less significant than biofilm formed on silicone. This fact may be attributed to the methodology used which was previously developed for biofilm formation on silicone pads [23, 24]. The process of candidal adhesion to acylic resins is complex. Previous studies have shown that a number of factors including the nutrient source, the sugar used for growth (glucose or sucrose), and the formation of pellicules from saliva or serum may influence the adhesion and colonization of Candida [7, 29].

We also used an in vivo G. mellonella infection model to evaluate the pathogenicity of oral and systemic Candida isolates. There are some benefits to using G. mellonella larvae as a model host to study Candida compare to other invertebrate models. For example, the larvae can be maintained at a temperature range from 25°C to 37°C, thus facilitating a number of temperature conditions under which fungi exist in either natural environmental niches or mammalian hosts. High temperatures can be prohibitive for the growth of C. elegans or Drosophila infection models. Our study used 37°C to mimic mammalian infection systems. G. mellonella also has the benefit of facile inoculation methods either by injection or topical application, where injection inoculation provides a means to deliver a precise amount of fungal cells [12, 27, 34]. By contrast, other systems, such as C. elegans, require infection through ingesting the pathogen. Since we included both albicans and non-albicans strains in our study we thought it prudent to use a model that ensured equal pathogen delivery rather than a model that would have an aversion to consuming some of the infecting agents.

As with the biofilm assays, the virulence levels of Candida isolates in G. mellonella were dependent on the species studied. Surprisingly, within the same species, oral isolates were as virulent as isolates from candidemia, the most common severe Candida infection. Previously, Cotter et al. [25] reported that it is possible to distinguish between different levels of pathogenicity within the genus Candida using G. mellonella larvae. We observed that G. mellonella showed mortality rates of 100% after injection with 105 cells of C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis, 87% with C. lusitaniae, 37% with C. novergensis, 25% with C. krusei, 20% with C. glabrata, and 12% with C. kefyr over a 96 hour period of incubation at 37°C. Cotter et al. [25] verified mortality rates of 90% for C. albicans, 70% for C. tropicalis, 45% for C. parapsilosis, 20% for C. krusei, and 0% for C. glabrata over a 72 hour period of incubation at 30°C after the injection with 106 cells of each Candida species. Probably, the virulence of the Candida strains in G. mellonella tested in this study were higher than the virulence of Candida strains observed by Cotter et al. [25] because of the difference of incubation temperature used. The temperature variations can affect gene expression and consequently the level of virulence of Candida strains [35].

Of note is that this is the first study to inoculate species of C. lusitaniae, C. norvegensis and C. dubliniensis in the G. mellonella model. Single isolates for C. lustaniae and C. norvegensis and two isolates of C. dubliniensis were included in our study. C. lusitaniae is considered an emerging non-albicans Candida species and isolates show resistance to amphotericin B. C. norvegensis appears to be a rare cause of human infection and the most of the isolates are resistant to fluconazole [36, 37]. There are limited data on the comparative virulence of C. lusitaniae and C. norvegensis in relation to C. albicans. In this study, C. lusitaniae and C. norvegensis were less virulent in G. mellonella than C. albicans.

Finally, in our study, C. dubliniensis isolates showed that the ability of biofilm formation and killing G. mellonella was similar to C. albicans. C. dubliniensis has been implicated in oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV-infected patients, althought it has also been isolated from other anatomical sites, including lungs, vagina, blood, and feces [38, 39]. Despite the significant phenotypic and genotypic similarities shared between C. albicans and C. dubliniensis, the comparative virulence of the two species is clearly a very complex topic [40, 41]. Borecká-Melkusová [42] verified that the biofilm formation in C. albicans was significantly lower than in C. dubliniensis, and Koga-Ito et al. [43] observed that the survival rate and dissemination capacity of C. dubliniensis in mice were lower than C. albicans.

Conclusion

In summary, in Candida spp., the ability of biofilm formation and virulence in the G. mellonella model were dependent on the species studied. For C. albicans the pathogenicity of oral isolates was similar to that of systemic isolates, suggesting that oral Candida infections should be taken seriously as they have the potential to be as equally morbid if they become systemic infections. Of note is that the penetration by C. albicans filaments is critical during the course of the infection in the Galleria tissue [17]. However, this model does not focus on invasion. Further studies are needed in order to study the ability of oral isolates to colonize and penetrate tissues.

References

Donnely RF, McCarron PA, Tunney MM: Antifungal photodynamic therapy. Microbiological Research. 2008, 163: 1-12. 10.1016/j.micres.2007.08.001.

Johnson DW, Cobb JP: Candida infection and colonization in critically ill surgical patients. Virulence. 2010, 1: 355-356. 10.4161/viru.1.5.13254.

Kourkoumpetis T, Manolakaki D, lmahos G, Chang Y, Alam HB, De Moya MM, Sailhamer EA, Mylonakis E: Candida infection and colonization among non-trauma emergency surgery patients. Virulence. 2010, 1: 359-366. 10.4161/viru.1.5.12795.

Hamza OJM, Matee MI, Moshi MJ, Simon EN, Mugusi F, Mikx FH, Heldermana WH, Rijs AJ, van der Ven AJ, Verweij PE: Species distribution and in vitro antifungal susceptibility of oral yeast isolates from Tanzanian HIV infected patients with primary and recurrent oropharyngeal candidiasis. BMC Microbiology. 2008, 8: 135-10.1186/1471-2180-8-135.

Silva S, Henriques M, Oliveira R, Williams D, Azeredo J: In vitro biofilm activity of non-Candida albicans Candida species. Current Microbiology. 2010, 61: 534-540. 10.1007/s00284-010-9649-7.

Silva S, Negri M, Henriques M, Oliveira R, Williams D, Azeredo J: Silicone colonization by non-Candida albicans Candida species in the presence of urine. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2010, 59: 747-754. 10.1099/jmm.0.017517-0.

Noumi E, Snoussi M, Hentati H, Mahdouani K, del Castillo L, Valentin E, Sentandreu R, Bakhrouf A: Adhesive properties and hydrolytic enzymes of oral Candida albicans strains. Mycopathologia. 2010, 169: 269-278. 10.1007/s11046-009-9259-8.

Nobile CJ, Nett JE, Andes DR, Mitchell AP: Function of Candida albicans adhesion Hwp1 in biofilm formation. Eukaryotic Cell. 2006, 5: 1604-1610. 10.1128/EC.00194-06.

Seneviratne CJ, Silva WJ, Jin LJ, Samaranayake YH, Samaranayake LP: Architectural analysis, viability assessment and growth kinetics of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata biofilms. Archives of Oral Biology. 2009, 54: 1052-1060. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2009.08.002.

Chamilos G, Lionakis MS, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP: Role of mini-host models in the study of medically important fungi. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2007, 7: 42-55. 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70686-7.

Mylonakis E, Aballay A: Worms and flies as genetically tractable animal models to study host-pathogen interactions. Infection and Immunity. 2005, 73: 3833-3841. 10.1128/IAI.73.7.3833-3841.2005.

Fuchs BB, Mylonakis E: Using non-mammalian hosts to study fungal virulence and host defense. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2006, 9: 346-351. 10.1016/j.mib.2006.06.004.

Mylonakis E: Galleria mellonella and the study of fungal pathogenesis: making the case for another genetically tractable model host. Mycopathologia. 2008, 165: 1-3. 10.1007/s11046-007-9082-z.

Bergin D, Murphy L, Keenan J, Clynes M, Kavanagh K: Pre-expose of yeast protects larvae of Galleria mellonella from a subsequent lethal infection by Candida albicans and is mediated by the increased expression of antimicrobial peptides. Microbes and Infection. 2006, 8: 2105-2112. 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.03.005.

Rowan R, Moran C, McCann M, Kavanagh K: Use of Galleria mellonella larvae to evaluate the in vivo anti-fungal activity of [Ag2(mal)(phen)3]. Biometals. 2009, 22: 461-467. 10.1007/s10534-008-9182-3.

Mowlds P, Kavanagh K: Effect of pre-incubation temperature on susceptibility of Galleria mellonella larvae to infection by Candida albicans. Mycopathologia. 2008, 165: 5-12. 10.1007/s11046-007-9069-9.

Fuchs BB, Eby J, Nobile CJ, El Khoury JB, Mitchell AP, Mylonakis E: Role of filamentation in Galleria mellonella killing by Candida albicans. Microbes and Infection. 2010, 12: 488-496. 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.03.001.

Badrane H, Cheng S, Nguyen MH, Jia HY, Zhang Z, Weisner N, Clancy CJ: Candida albicans IRS4 contributes to hyphal formation and virulence after the initial stages of disseminated candidiasis. Microbiology. 2005, 151: 2923-2931. 10.1099/mic.0.27998-0.

Costa CR, Pastos XS, Souza LKH, Lucena PA, Fernandes OFL, Silva MRR: Differences in exoenzyme production and adherence ability of Candida spp. isolates from catheter, blood and oral cavity. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo. 2010, 52: 139-143. 10.1590/S0036-46652010000300005.

Hasan F, Xess I, Wang X, Jain N, Fries BC: Biofilm formation in clinical Candida isolates and its association with virulence. Microbes and Infection. 2009, 11: 753-761. 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.04.018.

MähB B, Stehr F, Sichafer W, Neuber V: Comparison of standard phenotypic assays with a PCR method to discriminate Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis. Mycoses. 2005, 58: 55-61.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts: approved standard M27-A2. 2002, CLSO, Wayne, PA, USA

Nobile CJ, Mitchell AP: Regulation of cell-surface genes and biofilm formation by the C. albicans transcription factor Bcr1p. Current Microbiology. 2005, 15: 1150-1155.

Breger J, Fuchs BB, Aperis G, Moy TI, Ausubel FM, Mylonakis E: Antifungal chemical compounds identified using a C. elegans pathogenicity assay. PLoS Pathogens. 2007, 3: 168-178. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030168.

Cotter G, Doyle S, Kavanagh K: Development of an insect model for the in vivo pathogenicity testing of yeasts. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 2000, 27: 163-169. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2000.tb01427.x.

Brennan M, Thomas DY, Whiteway M, Kavanagh K: Correlation between virulence of Candida albicans mutants in mice and Galleria mellonella larvae. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 2002, 34: 153-157. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2002.tb00617.x.

Fuchs BB, O'Brien E, El Khoury JB, Mylonakis E: Methods for using Galleria mellonella as a model host to study fungal pathogenesis. Virulence. 2010, 1: 475-482. 10.4161/viru.1.6.12985.

Brown AJP, Odds FC, Gow NAR: Infection-related gene expression in Candida albicans. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2007, 10: 307-313. 10.1016/j.mib.2007.04.001.

Jin Y, Samaranayake LP, Samaranayake Y, Yip HK: Biofilm formation of Candida albicans is variably affected by saliva and dietary sugars. Archives of Oral Biology. 2004, 49: 789-798. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.04.011.

Thein ZM, Seneviratne CJ, Samaranayake YH, Samaranayake LP: Community lifestyle of Candida in mixed biofilms: a mini review. Mycoses. 2009, 52: 467-475. 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01719.x.

Willians DW, Kuriyama T, Silva S, Malic S, Lewis MAO: Candida biofilms and oral candidosis: treatment and prevention. Periodontology 2000. 2011, 55: 250-265. 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00338.x.

Peleg AY, Tampakakis E, Fuchs BB, Eliopouls GM, Moellering RC, Mylonakis E: Prokaryote-eukaryote interactions identified by using Caenorhabditis elegans. Proceedings of the Nationall Academy of Sciences USA. 2008, 105: 14585-14590. 10.1073/pnas.0805048105.

Silva WJ, Seneviratne J, Parahitiyawa N, Rosa EAR, Samaranayake LP, Del Bel Crury AA: Improvement of XTT assay performance for studies involving Candida albicans biofilm. Brazilian Dental Journal. 2008, 19: 364-369.

Cowen L, Singh SD, Köhler JR, Collins C, Zaas AK, Schell WA, Aziz H, Mylonakis E, Perfect JR, Whitesell L, Lindquist S: Harnessing Hsp90 function as a powerful, broadly effective therapeutic strategy for fungal infectious disease. Proceedings of the Nationall Academy of Sciences. 2009, 106: 2818-2823. 10.1073/pnas.0813394106.

Mylonakis E, Moreno R, El Khoury JB, Idnurm A, Heitman J, Calderwood SB, Ausubel FM, Diener A: Galleria mellonella as a model system to study Cryptococcus neoformans pathogenesis. Infection and Immunity. 2005, 73: 3842-3850. 10.1128/IAI.73.7.3842-3850.2005.

Krcmery V, Barnes AJ: Non-albicans Candida spp. causing fungaemia: pathogenicity and antifungal resistance. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2002, 50: 243-260. 10.1053/jhin.2001.1151.

Miceli MH, Díaz JA, Lee SA: Emerging opportunistic yeast infections. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2011, 11: 42-151.

Sullivan DJ, Moran GP, Pinjon E, Al-Mosaid A, Stokes C, Vaughan C, Coleman DC: Comparasion of the epidemiology, drug resistance mechanisms and virulence of Candida dublinienses and Candida albicans. FEMS Yeast Research. 2004, 4: 369-376. 10.1016/S1567-1356(03)00240-X.

Neppelenbroek KH, Campanha NH, Spolidorio DMP, Spolidorio LC, Séo RS, Pavarina AC: Molecular fingerprinting methods for the discrimination between C. albicans and C. dubliniensis. Oral Diseases. 2006, 12: 242-253. 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01189.x.

Sullivan D, Moran GP: Differential virulence of Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis: A role for Tor1 Kinase?. Virulence. 2011, 2: 77-81. 10.4161/viru.2.1.15002.

Vilela MM, Kamei K, Sano A, Tanaka R, Uno J, Takahashi I, Ito J, Yarita K, Miyaji M: Pathogenicity and virulence of Candida dubliniensis: comparison with C. albicans. Medical Mycology. 2002, 40: 249-257.

Borecká-Melkusová S, Bujdáková H: Variation of cell surface hydrophobicity and biofilm formation among genotypes of Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis under antifungal treatment. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 2008, 54: 718-724. 10.1139/W08-060.

Koga-Ito CY, Komiyama EY, Martins CAP, Vasconcellos TC, Jorge AOC, Carvalho YR, Prado RF, Balducci I: Experimental systemic virulence of oral Candida dubliniensis isolates in comparison with Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis and Candida krusei. Mycoses. 2011, 19: 278-85.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the São Paulo Council of Research - FAPESP, Brazil (Grant n° 09/52283-0) and Univ Estadual Paulista - PROPG/UNESP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

JCJ and EM participated in the design, implementation, analysis, interpretation of the results and wrote this manuscript. JMAHS collected the Candida strains from the oral cavity of HIV-positive patients. SFGV, ACBPC, VMCR and AOCJ performed the identification and the antifungal susceptibility of oral Candida isolates. BBF participated in the in vitro biofilm model and helped to draft the manuscript. MM participated in the G. mellonella assays. JJC identified the systemic Candida isolates. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Junqueira, J.C., Fuchs, B.B., Muhammed, M. et al. Oral Candida albicans isolates from HIV-positive individuals have similar in vitro biofilm-forming ability and pathogenicity as invasive Candida isolates. BMC Microbiol 11, 247 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-11-247

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-11-247