Abstract

Background

Ryegrasses and fescues (genera, Lolium and Festuca) are species of forage and turf grasses which are used widely in agricultural and amenity situations. They are classified within the sub-family Pooideae and so are closely related to Brachypodium distachyon, wheat, barley, rye and oats. Recently, a DArT array has been developed which can be used in generating marker and mapping information for ryegrasses and fescues. This represents a potential common marker set for ryegrass and fescue researchers which can be linked through to comparative genomic information for the grasses.

Results

A F2 perennial ryegrass genetic map was developed consisting of 7 linkage groups defined by 1316 markers and deriving a total map length of 683 cM. The marker set included 866 DArT and 315 gene sequence-based markers. Comparison with previous DArT mapping studies in perennial and Italian ryegrass (L. multiflorum) identified 87 and 105 DArT markers in common, respectively, of which 94% and 87% mapped to homoeologous linkage groups. A similar comparison with meadow fescue (F. pratensis) identified only 28 DArT markers in common, of which c. 50% mapped to non-homoelogous linkage groups. In L. perenne, the genetic distance spanned by the DArT markers encompassed the majority of the regions that could be described in terms of comparative genomic relationships with rice, Brachypodium distachyon, and Sorghum bicolor.

Conclusions

DArT markers are likely to be a useful common marker resource for ryegrasses and fescues, though the success in aligning different populations through the mapping of common markers will be influenced by degrees of population interrelatedness. The detailed mapping of DArT and gene-based markers in this study potentially allows comparative relationships to be derived in future mapping populations characterised using solely DArT markers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) is the most important forage grass of N. Europe and is also grown widely in temperate regions worldwide. It is a member of a group of inter-fertile, largely outbreeding, related species which encompass a number of ryegrasses and fescues (Lolium and Festuca spp.) including, Italian ryegrass (L. multiflorum) and meadow and tall fescue (F. pratensis and F. arundinacea). Because of their economic significance and evolutionary relationships, there has been interest in characterising these grasses in molecular terms both as individual species and as ancestral and recent hybrids.

Genetic maps have been established for ryegrasses and fescues largely as a consequence of the desire to understand the genetic architecture of both QTL and single genes which confer agriculturally important traits. Marker-based maps have progressed from linkage groups developed largely from restriction fragment-length polymorphisms (RFLPs) [1–5] to those developed from combinations of random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPDs), amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLPs) and microsatellites/simple sequence repeats (SSRs) [6–13]. While these have delivered their immediate aims, the lack of a comprehensive common set of reference markers has limited the number of opportunities to align these maps and, so, the associated trait data produced for different studies. Recognition of this for ryegrasses and fescues led to the manufacture of a Diversity Array Technology (DArT) array constructed from 40 ryegrass and fescue accessions [14] and a related open access database [15]. The hope was that this would encourage the use of a common marker set and so enable more efficient exploitation of the available genetic data for ryegrasses and fescues. This, in turn, would contribute towards both increasing our understanding of the genetics and biology of these grasses and the development of protocols for molecular breeding. The publication of perennial and Italian ryegrass and meadow fescue genetic maps and analyses of Lolium x Festuca hybrids [16, 17] integrating DArT markers indicates that this process is underway.

Ryegrasses are classified in the Pooideae subfamily within the Poaceae, along with wheat, barley, rye and oats, as well as the model monocot Brachypodium distachyon. Thus, ryegrasses and fescues are part of a group of closely related important model and crop species. Within the same clade (BEP), but in a different subfamily (Erhartoideae) is the other major monocot model and crop, rice. More distantly related grasses are classified in the PACMAD clade, which includes many of the tropical C4 cereals and grasses such as maize, Sorghum bicolor, pearl millet, sugar cane and Miscanthus spp [18]. For three of these grasses in particular, rice [19], B. distachyon[20], and S. bicolor[21], comprehensive genome assemblies and pseudomolecules have now been released; these enable whole genome sequence comparisons to be made between these species. Additionally, this allows for the alignment of genetic maps constructed from sequence-based markers to be made with these whole genome assemblies, so identifying conserved marker/sequence orders between species. From these orders, macrosyntenic relationships can be imputed in the absence of comprehensive sequence-based assemblies for ryegrasses and fescues. Thus, in ryegrass, for which there is currently limited publicly available sequence information, it has been possible to use its conserved syntenic relationships with the sequenced model genome of rice [22, 23] to suggest candidate genes underlying QTL [13, 24, 25].

In this report, we will describe the construction of a genetic linkage map in ryegrass consisting predominantly of DArT and gene-based markers. This allows for the DArT markers to be assigned to putative comparative genomic regions within this framework.

Methods

Plant material

The L. perenne (Lp) F2 mapping population (Lp1) used was based on a cross between inbred genotypes derived from the varieties Perma and Aurora. The development and use of this mapping population has been described previously [26].

Marker assays

Previous studies have reported the incorporation of RFLP, AFLP, isozyme, SSR and gene-based SNP markers into this F2 linkage map [2, 13, 22, 26, 27]. New markers developed from the present study were based on DArT technology.

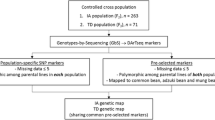

For the DArT markers, DNA was extracted from 94 genotypes of the F2 family using the QIAGEN DNeasy 96 Plant Kit (QIAGEN, Crawley, UK). These samples were processed on the high-density Lolium/Festuca DArT arrays [14] at Diversity Arrays Technology Pty Ltd, Canberra, Australia [28] and segregating markers identified. All DArT markers were given the prefix D (substituting ‘loPt-‘) followed by the unique six number identifier. For the gene-based SNP markers used for placing DArT markers in a comparative genomics context, the development rationale, primer and marker sequences and assays have been described previously [22]. Briefly, putative intra-exon PCR primers were designed based upon gene models developed as part of the rice (Oryza sativa; Os) genome sequencing programme [29] using gene models which spanned all 12 pseudomolecules of the rice genome. Using these primers, amplicons were derived from a DNA template pool consisting of equal quantities of genomic DNA from 96 individuals of the Lp1 mapping family (effectively recreating the genomic constitution of the original F1). Potential SNPs were identified by visual inspection of the chromatogram files and detected in the mapping family using protocols based on KASP technology [30]. KASP assays were developed and implemented by LGC Genomics Ltd., Herts., UK.

Genetic mapping

In order to minimise the number of missing data points the data was processed in two ways after scoring. Firstly, the family size was reduced to 86 genotypes which had been used for the generation of the majority of marker types (i.e., DArT, SNP and all the previously scored markers). Secondly, markers which gave identical segregation patterns, except for missing data, were all mapped as a single marker with missing genotype scores derived from the consensus. Genetic mapping on these datasets was carried out using JoinMap 3.0 [31] using the default conditions. Markers which could not be incorporated in rounds one or two (see Joinmap 3.0) were omitted from the final maps, but their likeliest positions reported in Additional file 1.

Comparative mapping

As described by King et al. [22], where sequences had been generated for mapped markers (e.g. the SNP markers) or were already published (many RFLP markers), these sequences were aligned with complete pseudomolecule (PM) assemblies for Os [29]; (v6.1/all_con), Brachypodium distachyon (Bd) and Sorghum bicolor (Sb) [32] (Bdistachyon_114.fa and Sbicolor_79.fa) using BLAST-generated sequence alignments with a cutoff threshold of e = <1e-005; see (Additional file 2). In each case, only the most significant BLAST alignment was used to assign putative orthology between the Lp marker sequences and the PM sequences for Os, Bd and Sb. The comparative relationships were described as plots of the genetic positions (cM) of sequenced markers on the Lp linkage groups (LG) against the physical positions (bp) of the putative orthologues on the Os, Bd and Sb PMs. In all cases, the genetic and physical positions were expressed as percentages of the total genetic distance of the LG or the complete PM length.

Results

Genetic mapping

Genetic mapping using JoinMap3.0 incorporated the new DArT data into the existing framework maps for this F2 population giving an overall map length of 683 cM defined by 1316 markers; an additional 66 DArT, 3 SNP, 3 SSR and a single AFLP marker could be assigned ‘best-fit’ positions (Additional file 1). The average interval between segregating markers was 0.92 cM, with the largest interval being 13.4 cM. Significant regions of distorted segregation were detected on LGs 5 and 7, as has previously been reported for this family [27]. The overall distribution of the markers was typical for linkage groups constructed for plant species with moderate to large sized genomes, with marked clustering (reduced recombination) around the putative centromeric regions and higher levels of recombination towards the ends of the linkage groups. The distribution of the different marker types is illustrated in Figure 1 and demonstrates the comprehensive genome sampling of the DArT markers relative to the gene-based SNP and other marker types, moderated by relative differences in recombination frequencies along the length of the LGs. Because of the low recombination frequencies in certain regions and the restricted family size, 771 markers (59%) showed no recombination with at least one other marker (Additional file 1).

L. perenne genetic map. Genetic map of the L. perenne F2 mapping population illustrating the relative distributions of marker types over the 7 linkage groups (C1-C7). For each linkage group, column 1 contains the DArT marker positions, column 2 framework marker positions excluding gene-based SNPs and column 3 the gene-based SNP marker positions.

DArT marker assays

Segregation data for a total of 1150 DArT markers was recorded, of which 942 could be associated with one or more markers in the existing LGs for the F2 family with a LOD ≥3. Of these 942, 867 could be assigned direct positions in the linkage maps and a further 66 ‘best-fit’ positions (Additional file 1). A comparison of maps produced with and without the inclusion of the DArT markers indicated no significant changes to marker orders (data not shown; compare with King et al. 2012 [22]). The overall total map length increased from 597 cM to 683 cM, this increase being due to the identification of new terminal markers, particularly on LGs 5, 6 and 7, rather than map expansion within the existing framework (Table 1). The DArT markers were fairly evenly distributed between the LGs except for LG4 to which 21% of the total number of DArT markers were assigned (mean per linkage group = 14.3%; Table 1). LG4 is also the longest linkage group (18% of the total genetic distance) and so the comparatively large number of DArT markers which map to LG4 may just be a reflection of this in combination with background variation. A similar pattern of results has previously been reported for Lp and Lm [16, 33]. However, it is possible that potential DArT markers (i.e.’ those selected for the array) may not have an even distribution across the genome.

Comparative mapping

A total of 315 gene-based markers mapped to the Lp1 family were used for establishing alignments with Os, Bd and Sb (Figure 2). These consisted of the 271 SNP markers, 37 RFLPs and 7 sequence tagged sites (STS). The mapping of these SNP markers in the absence of the DArT markers has been described previously [22] and the results are highly consistent with that study in terms of map orders and derived conserved syntenic relationships and also consistent with other Lolium and Festuca spp. studies in terms of comparative genomics [2, 4, 5, 13, 23, 27, 34].

Comparative genomic relationships between L. perenne, B. distachyon , S. bicolor and rice relative to DArT marker distribution. Scatter plot illustrating the conserved syntenic relationships between the relative position of gene-based markers on the L. perenne linkage groups (Lp1 study), the physical position of their most probable sequence alignments on the B. distachyon, S. bicolor and rice pseudomolecules and the genetic distance spanned by the DArT markers mapped to each L. perenne linkage group. The position of the S. bicolor markers from pseudomolecule 1 which align with genetic markers which map to L. perenne linkage group 4 are offset slightly to avoid direct overlap with the B. distachyon alignments to the same linkage group. Figure adapted from King et al. [22].

Discussion

While molecular genetic technologies have transformed our understanding of plant genome compositions and their interrelationships, they have yet to have a major impact on the plant breeding of many crops. This is largely due to the perceived cost/benefit ratio of applying these molecular technologies in different biological and commercial contexts, i.e., as influenced by the breeding systems and genetic complexities of different commercial plant varieties and the immediate economic value of individual crops. Ryegrasses are particularly challenging for the molecular breeder in that: a) they are, in the main, obligate outbreeders and so highly heterozygous; b) marketed varieties are frequently synthetic populations which are, genetically speaking, very distant from the tractable inbred lines predominant for barley, wheat and the F1 hybrids of maize; c) the main commercial value of ryegrass breeding is in the products of grassland agriculture rather than in the seed sales per se. As a consequence, molecular breeding of ryegrasses is still very much in development. As a contribution to this, the major purpose of this report is to add to the public body of knowledge on the genetic distribution of available marker sets for ryegrass and the relationship of these to established molecular genetic platforms as represented by the sequenced plant genomes of Os, Bd and Sb. This should allow the molecular ryegrass breeder to obtain extra leverage from these genetic and genomic resources in terms of comparative QTL analysis, gene prediction and consequent marker development.

Currently, there are few ryegrass and fescue studies that have allowed for detailed genome-wide comparisons to be made between different genetic maps; where present, linkages between different studies are dependent on the use of either a limited number of ‘historic’ RFLP and/or SSR markers [2, 10, 13]. The development of a high-density DArT marker array for ryegrasses and fescues now means that a large, common marker set can be applied to different ryegrass and fescue populations which can result in high density genetic maps and measurements of population interrelatedness. The major disadvantage to using DArT markers (as with AFLPs) in many population types is their genetic dominance, i.e., a DArT marker (allele) scored as present in a genotype could be either in the homozygous or heterozygous form. This has consequences in terms of predictive ability for linkages, allele frequencies and for marker trait associations. However, this is balanced by the ability of DArT markers to ‘capture’ the genetic space and it is sometimes possible to infer the dosage of a particular allele from linked co-dominant markers.

In this study we have presented a genetic map which places DArT markers in a detailed comparative genomic context. In order to incorporate as many markers of different types as possible, a reduced population size was employed with marker redundancy kept as low as possible. This minimised the number of missing data points which simplified the process of marker ordering on the individual linkage groups using JoinMap3.0. The consequence of this is that we were less likely to discover rarer recombination events that may have broken up some of the larger non-recombinant blocks of markers (Additional file 1). However, the uneven patterns of recombination we observed are not, primarily, artefacts of this experimental design and such patterns are consistently reported in ryegrass mapping studies with different population sizes [1, 2, 8, 12, 16, 33]. In summary, while this mapping approach may not describe all the recombination present, we hope that by combining the maximum number of DArT and gene-based markers in a single map and demonstrating that the DArT markers encompass the majority of the ‘comparative genome’ (Figure 1 and 2) it will enable inferences to be made about putative comparative relationships in ryegrass and fescue mapping studies based mostly (or entirely) on DArT markers. This may be particularly useful in population surveys which are not based on bi-parental mapping family designs (for detailed alignments between L. perenne and wheat and barley, see [22]).

Tomaszewski et al. [33] and Bartos et al. [16] recently published studies which integrated DArT markers into linkage maps developed for L perenne. (Lp2) L. multiflorum (Lm) and F. pratensis (Fp) mapping populations. The total number of DArT markers mapped in the different populations varied from 867 to 149 (Table 2) and comparisons of the Lp1, Lp2 and Lm Lolium populations identified between 80 and 105 markers in common (on a pairwise comparison basis) of which >85% map to similar positions on homologous and homoeologous linkage groups (Figure 3; Additional file 3). Comparing the Lp1 and Lp2 populations, of the 297 possible shared loci (i.e. the smaller number of DArT markers mapped in either population) c. 28% were putatively allelic (i.e., the same marker designation mapping to a similar position on the homologous/homoeologous linkage group); equivalent figures for the Lp1/Lm and Lp2/Lm comparisons were 17% and 13%, respectively and for the Lp1/Fp, Lp2/Fp and Lm/Fp comparisons, 9%, 5% and 11%, respectively. Thus, as would be expected, the greater the genetic distance between two genotypes or populations, the fewer the number of DArT markers that they had in common (a similar low number of common markers between the Lp1 population and a different Fp genotype has also been observed by the authors; unpublished).

DArT marker alignments between mapping studies in L. perenne , L. multiflorum and F. pratensis . A comparison of genetic positions of DArT markers common to L. perenne (Lp1, this study, yellow; Lp2, green [33]) L. multiflorum (Lm, purple) and F. pratensis (Fp, orange) [16] mapping populations. The 7 pairs of linkage groups on the left illustrate the relative positions of common markers which map to the same linkage group and those on the right, the relative positions of common markers which map to different linkage groups. The genetic position of each marker is expressed as a % of the total length (cM) of each linkage group.

A number of DArT markers with the same identifiers were, apparently, non-allelic in different populations (Table 2 and Figure 3; Additional file 3). While it is possible that some of these ‘discrepancies’ result from genuine genome rearrangements, it is likely that many result from cross-hybridisation of similar sequences on the arrays. For the Lp1/Lp2 comparison, 6% (n = 87) of the DArT markers were non-allelic; for the Lp1/Lm and Lp2/Lm comparisons 13% (n = 105) and 10% (n = 42), respectively, were non-allelic. For the comparisons between Lp1, Lp2, Lm and Fp the equivalent figures were 50% (n = 28) 0% (n = 8) and 15% (n = 20), respectively. Clearly, the low numbers of common markers in these latter comparisons do not allow any firm conclusions to be drawn, but the Lp1/Fp results would suggest that non-allelic cross hybridisation is likely to complicate direct map comparisons in wider crosses. As more studies using the DArT marker array are reported, it will be interesting to see if a core set of ‘consistent’ markers emerges for mapping both within and between different populations of ryegrasses and fescues.

Conclusion

This study describes an integration of 866 DArT markers into a comprehensive map of ryegrass which can be aligned with B. distachyon, rice and S. bicolor. In so doing, it is hoped that this will be useful resource for guiding the alignments of different ryegrass mapping and population studies, in order to maximise mutual transfers of information. It is likely that, in the near future, the sequencing and resequencing of the ryegrass genome will precipitate the development of economic genotyping-by-sequencing approaches which will be able to characterise allelic variation at far greater depth. However, until that is achieved common marker sets and comparative genomics are likely to guide the way forward for molecular plant breeding of ryegrasses.

References

Alm V, Fang C, Busso CS, Devos KM, Vollan K, Grieg Z, Rognli OA: A linkage map of meadow fescue (Festuca pratensis Huds.) and comparative mapping with other Poaceae species. Theor Appl Genet. 2003, 108 (1): 25-40. 10.1007/s00122-003-1399-5.

Armstead IP, Turner LB, King IP, Cairns AJ, Humphreys MO: Comparison and integration of genetic maps generated from F-2 and BC1-type mapping populations in perennial ryegrass. Plant Breed. 2002, 121 (6): 501-507. 10.1046/j.1439-0523.2002.00742.x.

Inoue M, Gao ZS, Hirata M, Fujimori M, Cai HW: Construction of a high-density linkage map of Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) using restriction fragment length polymorphism, amplified fragment length polymorphism, and telomeric repeat associated sequence markers. Genome. 2004, 47 (1): 57-65. 10.1139/g03-097.

Jones ES, Mahoney NL, Hayward MD, Armstead IP, Jones JG, Humphreys MO, King IP, Kishida T, Yamada T, Balfourier F, et al: An enhanced molecular marker based genetic map of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) reveals comparative relationships with other Poaceae genomes. Genome. 2002, 45 (2): 282-295. 10.1139/g01-144.

Sim S, Chang T, Curley J, Warnke SE, Barker RE, Jung G: Chromosomal rearrangements differentiating the ryegrass genome from the Triticeae, oat, and rice genomes using common heterologous RFLP probes. Theor Appl Genet. 2005, 110 (6): 1011-1019. 10.1007/s00122-004-1916-1.

Cogan N, Smith K, Yamada T, Francki M, Vecchies A, Jones E, Spangenberg G, Forster J: QTL analysis and comparative genomics of herbage quality traits in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2005, 110 (2): 364-380. 10.1007/s00122-004-1848-9.

Dumsday JL, Smith KF, Forster JW, Jones ES: SSR-based genetic linkage analysis of resistance to crown rust (Puccinia coronata f. sp lolii) in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne). Plant Pathol. 2003, 52 (5): 628-637. 10.1046/j.1365-3059.2003.00884.x.

Faville MJ, Vecchies AC, Schreiber M, Drayton MC, Hughes LJ, Jones ES, Guthridge KM, Smith KF, Sawbridge T, Spangenberg GC, et al: Functionally associated molecular genetic marker map construction in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2004, 110 (1): 12-32. 10.1007/s00122-004-1785-7.

Jensen LB, Andersen JR, Frei U, Xing YZ, Taylor C, Holm PB, Lubberstedt TL: QTL mapping of vernalization response in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) reveals co-location with an orthologue of wheat VRN1. Theor Appl Genet. 2005, 110 (3): 527-536. 10.1007/s00122-004-1865-8.

Studer B, Kolliker R, Muylle H, Asp T, Frei U, Roldan-Ruiz I, Barre P, Tomaszewski C, Meally H, Barth S, et al: EST-derived SSR markers used as anchor loci for the construction of a consensus linkage map in ryegrass (Lolium spp.). BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10: 177-10.1186/1471-2229-10-177.

Yamada T, Jones ES, Cogan NOI, Vecchies AC, Nomura T, Hisano H, Shimamoto Y, Smith KF, Hayward MD, Forster JW: QTL analysis of morphological, developmental, and winter hardiness-associated traits in perennial ryegrass. Crop Sci. 2004, 44 (3): 925-935. 10.2135/cropsci2004.0925.

Warnke SE, Barker RE, Jung G, Sim SC, Mian MAR, Saha MC, Brilman LA, Dupal MP, Forster JW: Genetic linkage mapping of an annual x perennial ryegrass population. Theor Appl Genet. 2004, 109 (2): 294-304.

Armstead IP, Turner LB, Marshall AH, Humphreys MO, King IP, Thorogood D: Identifying genetic components controlling fertility in the outcrossing grass species perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) by quantitative trait loci analysis and comparative genetics. New Phytol. 2008, 178 (3): 559-571. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02413.x.

Kopecky D, Bartos J, Lukaszewski AJ, Baird JH, Cernoch V, Koelliker R, Rognli OA, Blois H, Caig V, Luebberstedt T, et al: Development and mapping of DArT markers within the Festuca-Lolium complex. BMC Genomics. 2009, 10: 473-10.1186/1471-2164-10-473.

Germinate Grasses. [http://bioinf.scri.ac.uk/germinate_grasses/app/index.pl]

Bartos J, Sandve SR, Koelliker R, Kopecky D, Christelova P, Stoces S, Ostrem L, Larsen A, Kilian A, Rognli O-A, et al: Genetic mapping of DArT markers in the Festuca-Lolium complex and their use in freezing tolerance association analysis. Theor Appl Genet. 2011, 122 (6): 1133-1147. 10.1007/s00122-010-1518-z.

Kopecky D, Bartos J, Christelova P, Cernoch V, Kilian A, Dolezel J: Genomic constitution of Festuca x Lolium hybrids revealed by the DArTFest array. Theor Appl Genet. 2011, 122 (2): 355-363. 10.1007/s00122-010-1451-1.

NCBI Taxonomy Browser. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Undef&id=4479&lvl=3&lin=f&keep=1&srchmode=1&unlock,

Ouyang S, Zhu W, Hamilton J, Lin H, Campbell M, Childs K, Thibaud-Nissen F, Malek RL, Lee Y, Zheng L, et al: The TIGR Rice Genome Annotation Resource: Improvements and new features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35: D883-D887. 10.1093/nar/gkl976.

International Brachypodium I: Genome sequencing and analysis of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. Nature. 2010, 463 (7282): 763-768. 10.1038/nature08747.

Paterson AH, Bowers JE, Bruggmann R, Dubchak I, Grimwood J, Gundlach H, Haberer G, Hellsten U, Mitros T, Poliakov A, et al: The Sorghum bicolor genome and the diversification of grasses. Nature. 2009, 457 (7229): 551-556. 10.1038/nature07723.

King J, Armstead I, Harper J, Ramsey L, Snape J, Waugh R, James C, Thomas A, Gasior D, Kelly R, Roberts L, et al: Exploitation of interspecific diversity for monocot crop improvement. Heredity. 2012, 110: 478-483.

Pfeifer M, Martis M, Asp T, Mayer K, Lübberstedt T, Byrne S, Frei U, Studer B: The Perennial Ryegrass GenomeZipper – Targeted Use of Genome Resources for Comparative Grass Genomics. Plant Physiol. 2013, 161: 571-582. 10.1104/pp.112.207282.

Armstead I, Donnison I, Aubry S, Harper J, Hortensteiner S, James C, Mani J, Moffet M, Ougham H, Roberts L, et al: From crop to model to crop: identifying the genetic basis of the staygreen mutation in the Lolium/Festuca forage and amenity grasses. New Phytol. 2006, 172 (4): 592-597. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01922.x.

Armstead IP, Skot L, Turner LB, Skot K, Donnison IS, Humphreys MO, King IP: Identification of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne (L.)) and meadow fescue (Festuca pratensis (Huds.)) candidate orthologous sequences to the rice Hd1(Se1) and barley HvCO1 CONSTANS-like genes through comparative mapping and microsynteny. New Phytol. 2005, 167 (1): 239-247. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01392.x.

Turner LB, Cairns AJ, Armstead IP, Ashton J, Skot K, Whittaker D, Humphreys MO: Dissecting the regulation of fructan metabolism in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) with quantitative trait locus mapping. New Phytol. 2006, 169 (1): 45-57. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01575.x.

Armstead IP, Turner LB, Farrell M, Skøt L, Gomez P, Montoya T, Donnison IS, King IP, Humphreys MO: Synteny between a major heading-date QTL in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) and the Hd3 heading-date locus in rice. Theor Appl Genet. 2004, 108 (5): 822-828. 10.1007/s00122-003-1495-6.

Diversity Arrays Technology Pty Ltd. [http://www.diversityarrays.com/]

Rice Genome Annotation Project. [http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/]

Kbioscience. [http://www.lgcgenomics.com/genotyping/]

Van Ooijen JW, Voorrips RE: JoinMap® 3.0, Software for the calculation of genetic linkage maps. 2001, Wageningen, the Netherlands: Plant Research International

Phytozome. [http://www.phytozome.net/]

Tomaszewski C, Byrne SL, Foito A, Kildea S, Kopecky D, Dolezel J, Heslop-Harrison JS, Stewart D, Barth S: Genetic linkage mapping in an F2 perennial ryegrass population using DArT markers. Plant Breed. 2012, 131 (2): 345-349. 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2011.01944.x.

King J, Armstead IP, Donnison SI, Roberts LA, Harper JA, Skot K, Elborough K, King IP: Comparative analyses between Lolium/Festuca introgression lines and rice reveal the major fraction of functionally annotated gene models is located in recombination-poor/very recombination-poor regions of the genome. Genetics. 2007, 177: 597-606. 10.1534/genetics.107.075515.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research grant BB/E00654X/1 and an Institute Strategic Programme Grant (IBERS, Aberystwyth University) awarded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), UK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JK, IK and IA conceived and designed the experiments; JK, AT, CJ and IA carried out the molecular genetic analyses; IA drafted the manuscript, JK, IK and IA compiled the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

King, J., Thomas, A., James, C. et al. A DArT marker genetic map of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) integrated with detailed comparative mapping information; comparison with existing DArT marker genetic maps of Lolium perenne, L. multiflorum and Festuca pratensis. BMC Genomics 14, 437 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-14-437

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-14-437