Abstract

Background

Alu elements are Short INterspersed Elements (SINEs) in primate genomes that have proven useful as markers for studying genome evolution, population biology and phylogenetics. Most of these applications, however, have been limited to humans and their nearest relatives, chimpanzees. In an effort to expand our understanding of Alu sequence evolution and to increase the applicability of these markers to non-human primate biology, we have analyzed available Alu sequences for loci specific to platyrrhine (New World) primates.

Results

Branching patterns along an Alu sequence phylogeny indicate three major classes of platyrrhine-specific Alu sequences. Sequence comparisons further reveal at least three New World monkey-specific subfamilies; Alu Ta7, Alu Ta10, and Alu Ta15. Two of these subfamilies appear to be derived from a gene conversion event that has produced a recently active fusion of Alu Sc- and Alu Sp-type elements. This is a novel mode of origin for new Alu subfamilies.

Conclusion

The use of Alu elements as genetic markers in studies of genome evolution, phylogenetics, and population biology has been very productive when applied to humans. The characterization of these three new Alu subfamilies not only increases our understanding of Alu sequence evolution in primates, but also opens the door to the application of these genetic markers outside the hominid lineage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

SINEs (Short INterspersed Elements) are powerful tools for systematic and population biologists [1–8]. Examples of phylogenies elucidated using the SINE method include the use of SINEs to support the hypothesis that cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises) form a clade within Artiodactyla [9], clarification of relationships between cichlid fishes [10–12] and the resolution of the human-chimpanzee-gorilla trichotomy [5]. Although applications of SINE elements to resolve population dynamics have been limited to humans [13–19] and, to a lesser extent, cichlid fishes [11, 20, 21], these studies have been very successful in revealing patterns of variation and there is every reason to believe that they can be as productively applied to other species.

One reason for the success of SINEs as phylogenetic and population genetic markers is that their mode of evolution is unidirectional [3, 4, 7, 8, 22]. This characteristic allows for a confident inference that the ancestral state is the absence of the SINE at each locus. Because there is no known mechanism for the specific removal of SINEs from any genome [4, 23], individual SINEs are generally thought to be homoplasy-free characters [4, 7, 17, 22–25].

Alu elements are primate-specific SINEs of ~300 bp. These elements have been extremely successful at propagating in primate genomes as evidenced by the fact that they make up ~10% of the human genome by mass [23, 26]. Distinct subfamilies of Alu elements in the human genome have been described in detail [17, 18, 23, 27–32]. Examination of these young subfamilies has provided us with clues as to the mobilization dynamics and evolution of Alu elements in the hominid lineage. Characterization of Alu mobilization in non-human primates has not been as complete. The ascertainment of lineage-specific subfamilies of Alu elements would increase our understanding of mobile element evolution in these organisms and allow for the development of SINE-based studies of population and evolutionary patterns.

We recently used Alu insertion loci to clarify various relationships among platyrrhine (New World monkeys, NWM) and cercopithecid (Old World monkeys) primates [33, 34]. These projects produced examples of Alu insertions present in a wide variety of lineages along the primate tree. We have performed a phylogenetic analysis of the Alu sequences themselves (focusing on the platyrrhine-specific insertions) in order to characterize the evolutionary history of Alu lineages that have been or currently are retrotransposition competent in some non-human primates.

Results and discussion

Platyrrhine-specific Alu sequences were obtained from the data sets used in Ray et al. [34] When available, the sequences from multiple taxa at a particular locus were aligned and a consensus sequence generated to create an approximation of the sequence of the original insertion. A total of 48 platyrrhine-specific insertions were collected. All selected sequences were examined for the presence of target site duplications (TSDs). The presence of these TSDs along with the absence of each marker in hominid and cercopithecid taxa (and from the genomes of other platyrrhine primates in many cases) serves to verify that the elements are the result of retrotransposition events and not segmental duplications. To trim potentially long branches and to verify the ability of the approach to recover previously established relationships among reference sequences, we added the consensus sequences for Alu elements specific to hominids (Alu Ya5, Alu Ya5a2, Alu Yb8, Alu Yb9, Alu Yc1, Alu Yc2, Alu Yd3, Alu Yd6, and Alu Ye5) [18, 30–32, 35–37]. We also included the canonical Alu consensus sequences for the Jb, Sc, Sg, Sp, Sq, Sx, and Y subfamilies [38–40] and rooted the tree on Alu Jb based on previously established relationships [40–42].

The methods used to identify informative loci among cercopithecid taxa primarily involved a linker-PCR strategy using two Alu selection primers [33]. Unfortunately, this introduced a sequence bias toward particular subfamilies of recently integrated or lineage specific Alu elements. The strategy used to identify informative platyrrhine loci, on the other hand, used a combined computational-experimental approach. Over half of the loci identified were derived from Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) sequences and thus no bias was introduced. In addition, a wide variety of primers was used in the linker-PCR approach; as a consequence, the bias was reduced for experimentally-derived loci. Because of the bias in the data derived from the cercopithecids, we have not included these Alu sequences in the analyses. For platyrrhine Alu lineages, however, more confident inferences can be made.

Tree topologies recovered using Bayesian and parsimony criteria were generally congruent (Fig. 1). Minor differences in the placement of some sequences are observed but the well-supported clades recovered by the Bayesian analysis are often present in the parsimony consensus trees with reasonable support (>75%). However, bootstrap support on the parsimony-based cladogram was not as high for several of the major nodes found on the Bayesian tree. We suspect that this is due to the hybrid (partially gene converted) nature of 31 sequences that share diagnostic features of both Alu Sc-derived and Alu Sp derived elements (see below for a full discussion). Given the assumptions inherent in parsimony-based analyses (i.e. incremental sequence-based changes) hybrid elements that accumulated a whole suite of character states as a unit and that define other lineages in the data set would be expected to cause significant problems. Supplemental analyses with the hybrid elements removed confirmed this suspicion by raising support values at some nodes over 20 points (data not shown). The reduced tree-search method used is also thought to recover lower bootstrap support values than more traditional methods [43]. For these reasons, we have chosen to base our major conclusions on the topology and support values present on the Bayesian tree.

A) Majority-rules consensus of 10,000 trees generated using a Bayesian approach. Support values greater than 0.85 are indicated on relevant nodes. The major platyrrhine clades (A, B, C, and D) are indicated. Within clade D, members of subfamily Alu Ta10 are underlined. B) Majority-rules consensus tree of 107,470 equally parsimonious trees generated as described in the Methods section. Bootstrap values for nodes with greater than 50% support are indicated. Sequences representing well-supported clades from the Bayesian tree are also indicated.

Within that tree, the established relationships between canonical Alu consensus sequences were recovered as expected. The Alu Jb subfamily is basal to the remaining Alu sequences and relationships between the various Alu S subfamilies are similar to the results of Kapitonov and Jurka [39]. Among the New World primate Alu sequences all but three platyrrhine-specific sequences fall within a well supported Alu Sc-Alu Y derived clade. This topology suggests that at there may have been three Alu lineages active at the time of the platyrrhine-catarrhine divergence around 35–40 million years ago [44]: an Alu Y progenitor; Alu Sp; and, Alu Sc. The three platyrrhine-specific Alu insertions that clustered outside the major platyrrhine Alu Sc/Alu Y-derived clade were 'All_NWM_Locus_1', 'All_NWM_Locus_15', and 'All_NWM_Locus_31'. Each of these insertions is present in all tested platyrrhine taxa, suggesting that they occurred before the radiation of the New World monkeys into three recognized families, (Cebidae, Atelidae and Pitheciidae). The Alu sequence at 'All_NWM_Locus_1' appears to be derived from an Alu Sp source gene. Direct observation of the Alu sequence confirms the presence of several Alu Sp diagnostic sites in this element (see supplemental alignments). Based on our analyses, the sequence for 'All_NWM_Locus_15' appears to be derived from an Alu Y progenitor. There is no significant support for the node, however, and it should be noted that this is merely a suggestion based on the topology of the tree. Thus, an Alu Y progenitor, Alu Sp, and Alu Sc were all active around the time of the split. The source of the sequence at 'All_NWM_Locus_31' is unclear given the differences in placement between the Bayesian and parsimony analyses. RepeatMasker [45] lists the element as belonging to the Alu Sg lineage. Thus, it may represent a fourth lineage that was active early in the evolution of New World monkeys.

A majority of the Alu sequences specific to various New World monkeys are most closely related to an Alu Sc and there are four well-supported clades within this group. Clade A is represented by two sequences that were found only in members of Pitheciidae. The insertions 'Callicebus_83' and 'Pithecia_46', were specific to their respective Pitheciid genera, and they share eight exclusive non-CpG mutations when compared to Alu Sc and other Alu Sc-like sequences (Bayesian support = 1.00). The close relationship between these sequences was also recovered in the parsimony analysis. While we will not assign them to a new subfamily based on only two sequences, we suggest that they are good candidates for a Pitheciid-specific lineage.

A second clade (B) within the putative Alu Sc-derived group was also highly supported (0.99) and was represented an insertion identified in all platyrrhine primates ('All_NWM_Locus_26'), as well as in two Atelid taxa ('Lago_and_Atel_20') and in all members of Cebidae and Atelidae ('Cebid_Atelid_Locus_14'). These sequences may represent an Alu Sc-derived subfamily. However, this cluster was based on only a few sequences and on shared mutations at CpG sites; thus, it should be interpreted cautiously. An alternative is that these and the other elements in this group represent true Alu Sc insertions that have continued to accumulate in platyrrhine genomes throughout their evolution. This is not unlikely given the recent observations of potentially polymorphic Alu Sc loci [46] and relatively recent Alu Sx insertions in humans [47]. The 'stealth' model of Alu evolution and dispersal reported by Han et al. [48] also predicts low levels of activity for older Alu subfamiles. Alu Sc may represent a hardy subfamily that has remained active at a low level for long periods of time in a variety of primate genomes.

Clade C (support = 0.99) comprises five sequences characterized by 11 shared mutations (including a 7-base duplication) that distinguish them from Alu Sc. Sequences in this clade are distributed among members of families Pitheciidae and Atelidae. One interpretation of this pattern is the emergence of the source gene prior to the expansion of a Pitheciid-Cebid clade but after the divergence of Atelid taxa. This hypothesis is unlikely, however, given the results of Ray et al. [34] in which it was made clear that family Pitheciidae was the first to diverge from the early platyrrhine groups. We suggest instead that the source gene emerged after the divergence of platyrrhine and catarrhine primates but before the platyrrhine radiation 17–20 mya [49, 50], and that none of these elements was recovered for Cebid taxa due to sampling error. Additional work will be required to test this hypothesis.

Clade D is the largest of the clearly definable platyrrhine Alu clades, comprising 31 sequences from all three platyrrhine families. It is well-supported (1.00) and is distinguished by numerous shared mutations among its members. Of the new subfamilies described here, this lineage is particularly interesting because of its apparently unique origin. Close examination of the sequences reveals four shared Alu Sc diagnostic mutations at the 5' end of the elements; however, at the 3' end of the elements, there are five additional diagnostic sites characteristic of the Alu Sp subfamily. Examples of 'hybrid' elements have been described previously [17, 25, 29], but these represented individual instances involving the gene conversion of Alu elements already present in the genome. That does not appear to be the case here.

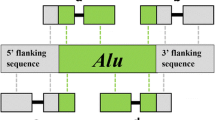

The presence of 31 distinct elements harboring this combination of Alu Sc and Alu Sp diagnostic mutations (plus three additional shared mutations) suggests that there is a recently active source gene with these characteristics. We propose that a source gene (most likely derived from Alu Sc) existed early in platyrrhine primate evolution and that the 3' end of the element was subjected to a gene conversion event via any of the three potential models described by Kass et al. [51]. Starting somewhere between bases 199 and 226 and continuing to the end of the element, the conversion event resulted in the replacement of the sequence of the source gene with sequence from an Alu Sp-like element (Fig. 2). The result was a 'fusion' element that remained active and may still be active in the genomes of several platyrrhine primates.

Multiple sequence alignment of three canonical reference sequences (Alu Jo, Alu Sc, and Alu Sp) with the new consensus sequences described in this work. Identical sequence residues are indicated by ".". Indels events are indicated by "-". Diagnostic mutations characteristic of Alu Sc and Alu Sp that are shared by the new consensus sequences are shaded. Substitutions distinguishing all Alu T subfamily members from Alu Sc are boxed.

This group of elements can be further subdivided into two subfamilies based on additional shared diagnostic mutations in what appears to be the more recently derived subfamily. In addition to the Alu Sp and Alu Sc derived sites and the three additional distinguishing sites, 21 elements share four unique mutations. Thus, clade D can be subdivided into two subfamilies consisting of 10 and 21 elements, respectively (see supplemental alignments).

These two subfamilies share two diagnostic positions with the previously mentioned clade C 5' to the appearance of the Alu Sp indicative sites. Thus, we believe that these three groups of sequences represent a new platyrrhine-specific subfamily we dubbed Alu T. We chose this designation based on the nomenclature proposed by Batzer et al. [38] in which younger subfamilies are assigned later letters of the alphabet. This is followed by a lowercase letter designating the order of publication, and a numerical designation indicating the number of diagnostic sites that differentiate it from the subfamily consensus. Because this group was similar to and apparently derived from Alu Sc, Alu T was most appropriate. It is distinguished from Alu Sc by the two aforementioned diagnostic mutations and can currently be divided into three subfamilies; Alu Ta7, Alu Ta10, and Alu Ta15 (Fig. 2). For reference, we have included a hypothetical Alu T consensus sequence based on the diagnostic sites shared by the Ta5, Ta10, and Ta15 consensi and the presumed ancestral sequence, Alu Sc, in figure 2.

Represented by 21 sequences, Alu Ta15 was only found in Cebid taxa (Aotus, Callithrix, and Siamiri). Alu Ta10 is represented by ten sequences and was recovered in members of all three platyrrhine families. The distribution of this subfamily of elements among platyrrine taxa and the pattern of shared diagnostic sites suggest that the Alu Ta10 family expanded earlier in platyrrhine evolution and may have given rise to the Alu Ta15 subfamily. A larger sample based solely on elements derived from unbiased methods will be required to test this hypothesis and is currently underway.

Conclusion

The identification of three (potentially four) new subfamilies that are unique to platyrrhine primates represents a step forward in our understanding of the evolution of Alu elements in the genomes of non-hominid primates. Further, this is the first report of a unique mechanism of Alu subfamily generation. Until now, the evolution of Alu subfamilies could easily be described using the sequential accumulation of diagnostic mutations. For example, the hominid Alu subfamily Alu Yb currently consists of four variants, Yb7, Yb8, Yb9, and Yb11 [30, 31, 52]. Patterns of sequence variation clearly illustrate the hierarchical nature of sequence evolution in this family. Yb9 exhibits all of the diagnostic mutations defining Alu Yb7 and Alu Yb8 as well as its own signature mutation. Alu Yb11 follows suit by exhibiting all of the Alu Yb9 mutations plus two others. This pattern is confirmed using age estimates that suggest Alu Yb7 is the oldest and Alu Yb11 is the youngest. The Alu Ta10 and Alu Ta15 subfamilies represent the first documented cases of a recently active 'fusion' element in which the diagnostic mutations were not accumulated gradually over time; instead, they represent the sudden incorporation of several signature mutations by way of a gene conversion event. Thus, a new mechanism of Alu subfamily generation, though previously considered possible [29], has now been substantiated in the genome.

On a more practical level, a number of questions raised in other taxonomic analyses of New World monkeys can now be better addressed [1, 34, 53–60] given the data presented here. We can confidently assign subfamily status to certain individual Alu elements in platyrrhine genomes. Thus, we are able to target particular Alu subfamilies with known expansion timeframes to address branching patterns for particular primate lineages. This technique has previously proven valuable. For example, by combining a targeted analysis of the Alu Ye5 subfamily with sequence database searches for additional informative loci, we were able to confidently address the human-chimpanzee-gorilla trichotomy [5]. Application of similar techniques to other primates can easily be adapted by using the linker protocols described in Ray et al. [34], Xing et al. [33] and Roy et al. [61] and by computational analyses of existing sequence data.

At the population level, the amplification dynamics of Alu elements have been well characterized in humans and even in chimpanzees, but have not been investigated extensively in other primates. This is unfortunate given their utility in studies of genome evolution in humans and chimpanzees [62–64], population biology in humans [13, 15, 16, 27, 65–74], and phylogenetic analysis at all levels of the primate tree [2, 5, 6, 33, 34, 41, 75]. Knowledge of these subfamilies will aid in the development of markers useful for all of the above tasks. For example, given the endangered status of many New World taxa, the existence of easy-to-ascertain markers (via a single PCR) to identify species-specific Alu insertions in tissues of unknown origin will be a boon to conservation biologists and to population geneticists. Similar genetic systems have already proven useful in other taxa ranging from humans to waterfowl [76–78]. As one simple example, we now use many of the Alu loci used in this study to verify the identity of cell lines in our laboratory. Using a single PCR to amplify a taxon-specific Alu insertion is quick and efficient when compared to methods that involve morphological analysis (if possible on a tissue sample) or amplification and sequencing of DNA.

In this study we have identified diagnostic mutations for platyrrhine specific subfamilies. The identification of particular Alu lineages is the critical first step in identifying polymorphic elements in a primate taxon [17, 18, 31, 61]. By identifying the subfamilies that are specific to particular taxa, researchers are now better able to use previously established techniques that take advantage of diagnostic mutations to identify useful markers at various taxonomic levels. The essentially homoplasy free nature of SINE markers makes them in some ways superior to other commonly used markers for population genetics [3, 4, 10, 12, 22, 34]. Thus we see this as the beginning of a series of studies in which the SINE method of population genetic analysis will be expanded beyond our own species.

Methods

Insertion/deletion (indels) events play a significant role in defining Alu subfamilies. For this reason, the phylogenetic method we used to reconstruct relationships was based primarily on the Bayesian method implemented by MrBayes, Ver. 3.1 [79, 80]. We chose this method because of its robustness and its ability to take advantage of information present in the form of insertion/deletion events in the alignment. We partitioned the data into two sets, sequence data and gap data. For partition one, sequence parameters were estimated from the data The second partition was generated using indels that were present in two or more sequences. These were coded as present (sequence) or absent (gap). For the second data partition, we estimated rates of indel occurrence from the data and corrected for ascertainment bias by setting the coding option to 'variable' as per the MrBayes manual.

Two simultaneous Markov chain Monte Carlo analyses were performed using one cold and three heated chains (temperature set to default 0.2) for each analysis. We ran the analysis for 7.5 million generations, sampling the trees every 100 generations. At ~6.13. million generations, the standard deviation of split frequencies consistently reached a value of <0.01, indicating that both analyses had begun converging on similar trees. We discarded the first 6.5 million generations as burn-in and generated a majority-rules consensus tree. Nodes with probability values of 0.85 to 0.89 were considered to have low support, 0.90 to 0.94 to have moderate support and nodes greater than 0.95 to be highly supported [80].

As a comparison, we also performed a parsimony analysis of the data in PAUP* v4.0b10 [81]. Non-CpG dinucleotides were weighted at six times the value of CpG dinucleotides [82] and gaps were treated as a fifth character state. The size of the data set made a bootstrap analysis using a full heuristic search for each replicate impractical. For this reason, we employed a reduced tree-search bootstrapping method as described by DeBry and Olmstead [43] to ascertain support for nodes.

The sequences from each clearly defined clade (see Results and Discussion) were collected and examined for shared mutations that presumably represent diagnostic mutations or positions characteristic of mobile element subfamilies. Consensus sequences for each of these groups were constructed. For non-CpG sites, a simple majority-rules approach was taken to obtain the consensus for the site. Alu elements, however, are rich in CpG dinucleotides that are known to mutate at a 6-fold higher rate than non-CpG sites [82]. These sites tend to be highly variable and could represent a problem when determining the identity. We addressed this issue by examining types of variation at potential CpG sites and by referring to the presumed ancestral sequences. First, dinucleotide sites exhibiting high diversity that comprised primarily both CpA and TpG dinucleotides were assumed to be highly mutable CpG sites that decayed as the result of the spontaneous deamination of 5-methylcytosine. When it remained unclear whether or not the site should be considered a CpG dinucleotide, we referred to the Alu Sc or Alu Sp consensus sequences to determine the likely ancestral state for the site and made the appropriate assignment.

Sequence alignments used for phylogenetic analysis and for the generation of consensus sequences are available online as additional files.

Abbreviations

- NWM:

-

New world monkeys

- Mya:

-

million years ago

- hLRT:

-

hierarchical likelihood ratio test

- AIC:

-

Akaike Information Criterion

- Indels:

-

insertion/deletion events

References

Schmitz J, Roos C, Zischler H: Primate phylogeny: molecular evidence from retroposons. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005, 108: 26-37. 10.1159/000080799.

Schmitz J, Ohme M, Zischler H: SINE insertions in cladistic analyses and the phylogenetic affiliations of Tarsius bancanus to other primates. Genetics. 2001, 157: 777-784.

Shedlock AM, Takahashi K, Okada N: SINEs of speciation: tracking lineages with retroposons. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2004, 19: 545-553. 10.1016/j.tree.2004.08.002.

Shedlock AM, Okada N: SINE insertions: powerful tools for molecular systematics. Bioessays. 2000, 22: 148-160. 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200002)22:2<148::AID-BIES6>3.0.CO;2-Z.

Salem AH, Ray DA, Xing J, Callinan PA, Myers JS, Hedges DJ, Garber RK, Witherspoon DJ, Jorde LB, Batzer MA: Alu elements and hominid phylogenetics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003, 100: 12787-12791. 10.1073/pnas.2133766100.

Roos C, Schmitz J, Zischler H: Primate jumping genes elucidate strepsirrhine phylogeny. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004, 101: 10650-10654. 10.1073/pnas.0403852101.

Miyamoto MM: Molecular systematics: Perfect SINEs of evolutionary history?. Current Biology. 1999, 9: R816-9. 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80498-9.

Salem AH, Ray DA, Batzer MA: Identity by descent and DNA sequence variation of human SINE and LINE elements. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005, 108: 63-72. 10.1159/000080803.

Shimamura M, Yasue H, Ohshima K, Abe H, Kato H, Kishiro T, Goto M, Munechika I, Okada N: Molecular evidence from retroposons that whales form a clade within even-toed ungulates. Nature. 1997, 388: 666-670. 10.1038/41759.

Takahashi K, Terai Y, Nishida M, Okada N: A novel family of short interspersed repetitive elements (SINEs) from cichlids: the patterns of insertion of SINEs at orthologous loci support the proposed monophyly of four major groups of cichlid fishes in Lake Tanganyika. Mol Biol Evol. 1998, 15: 391-407.

Takahashi K, Terai Y, Nishida M, Okada N: Phylogenetic relationships and ancient incomplete lineage sorting among cichlid fishes in Lake Tanganyika as revealed by analysis of the insertion of retroposons. Mol Biol Evol. 2001, 18: 2057-2066.

Takahashi K, Nishida M, Yuma M, Okada N: Retroposition of the AFC family of SINEs (short interspersed repetitive elements) before and during the adaptive radiation of cichlid fishes in Lake Malawi and related inferences about phylogeny. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 2001, 53: 496-507. 10.1007/s002390010240.

Bamshad MJ, Wooding S, Watkins WS, Ostler CT, Batzer MA, Jorde LB: Human population genetic structure and inference of group membership. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2003, 72: 578-589. 10.1086/368061.

Bamshad M, Kivisild T, Watkins WS, Dixon ME, Ricker CE, Rao BB, Naidu JM, Prasad BV, Reddy PG, Rasanayagam A, Papiha SS, Villems R, Redd AJ, Hammer MF, Nguyen SV, Carroll ML, Batzer MA, Jorde LB: Genetic evidence on the origins of Indian caste populations. Genome Research. 2001, 11: 994-1004. 10.1101/gr.GR-1733RR.

Batzer MA, Stoneking M, Alegria-Hartman M, Bazan H, Kass DH, Shaikh TH, Novick GE, Ioannou PA, Scheer WD, Herrera RJ, Deininger PL: African origin of human-specific polymorphic Alu insertions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994, 91: 12288-12292.

Perna NT, Batzer MA, Deininger PL, Stoneking M: Alu insertion polymorphism: a new type of marker for human population studies. Human Biology. 1992, 64: 641-648.

Salem AH, Kilroy GE, Watkins WS, Jorde LB, Batzer MA: Recently integrated Alu elements and human genomic diversity. Mol Biol Evol. 2003, 20: 1349-1361. 10.1093/molbev/msg150.

Otieno AC, Carter AB, Hedges DJ, Walker JA, Ray DA, Garber RK, Anders BA, Stoilova N, Laborde ME, Fowlkes JD, Huang CH, Perodeau B, Batzer MA: Analysis of the human Alu Ya-lineage. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2004, 342: 109-118. 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.016.

Ray DA, Walker JA, Hall A, Llewellyn B, Ballantyne J, Christian AT, Turteltaub K, Batzer MA: Inference of human geographic origins using Alu insertion polymorphisms. Forensic Science International. 2005, 153: 117-124. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.10.017.

Terai Y, Takahashi K, Nishida M, Sato T, Okada N: Using SINEs to probe ancient explosive speciation: "hidden" radiation of African cichlids?. Mol Biol Evol. 2003, 20: 924-930. 10.1093/molbev/msg104.

Terai Y, Takezaki N, Mayer WE, Tichy H, Takahata N, Klein J, Okada N: Phylogenetic relationships among East African haplochromine fish as revealed by short interspersed elements (SINEs). Journal of Molecular Evolution. 2004, 58: 64-78. 10.1007/s00239-003-2526-2.

Hillis DM: SINEs of the perfect character. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999, 96: 9979-9981. 10.1073/pnas.96.18.9979.

Batzer MA, Deininger PL: Alu repeats and human genomic diversity. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2002, 3: 370-379. 10.1038/nrg798.

Hamdi H, Nishio H, Zielinski R, Dugaiczyk A: Origin and phylogenetic distribution of Alu DNA repeats: irreversible events in the evolution of primates. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1999, 289: 861-871. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2797.

Roy-Engel AM, Carroll ML, El-Sawy M, Salem AH, Garber RK, Nguyen SV, Deininger PL, Batzer MA: Non-traditional Alu evolution and primate genomic diversity. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2002, 316: 1033-1040. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5380.

Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, Funke R, Gage D, Harris K, Heaford A, Howland J, Kann L, Lehoczky J, LeVine R, McEwan P, McKernan K, Meldrim J, Mesirov JP, Miranda C, Morris W, Naylor J, Raymond C, Rosetti M, Santos R, Sheridan A, Sougnez C, Stange-Thomann N, Stojanovic N, Subramanian A, Wyman D, Rogers J, Sulston J, Ainscough R, Beck S, Bentley D, Burton J, Clee C, Carter N, Coulson A, Deadman R, Deloukas P, Dunham A, Dunham I, Durbin R, French L, Grafham D, Gregory S, Hubbard T, Humphray S, Hunt A, Jones M, Lloyd C, McMurray A, Matthews L, Mercer S, Milne S, Mullikin JC, Mungall A, Plumb R, Ross M, Shownkeen R, Sims S, Waterston RH, Wilson RK, Hillier LW, McPherson JD, Marra MA, Mardis ER, Fulton LA, Chinwalla AT, Pepin KH, Gish WR, Chissoe SL, Wendl MC, Delehaunty KD, Miner TL, Delehaunty A, Kramer JB, Cook LL, Fulton RS, Johnson DL, Minx PJ, Clifton SW, Hawkins T, Branscomb E, Predki P, Richardson P, Wenning S, Slezak T, Doggett N, Cheng JF, Olsen A, Lucas S, Elkin C, Uberbacher E, Frazier M, Gibbs RA, Muzny DM, Scherer SE, Bouck JB, Sodergren EJ, Worley KC, Rives CM, Gorrell JH, Metzker ML, Naylor SL, Kucherlapati RS, Nelson DL, Weinstock GM, Sakaki Y, Fujiyama A, Hattori M, Yada T, Toyoda A, Itoh T, Kawagoe C, Watanabe H, Totoki Y, Taylor T, Weissenbach J, Heilig R, Saurin W, Artiguenave F, Brottier P, Bruls T, Pelletier E, Robert C, Wincker P, Smith DR, Doucette-Stamm L, Rubenfield M, Weinstock K, Lee HM, Dubois J, Rosenthal A, Platzer M, Nyakatura G, Taudien S, Rump A, Yang H, Yu J, Wang J, Huang G, Gu J, Hood L, Rowen L, Madan A, Qin S, Davis RW, Federspiel NA, Abola AP, Proctor MJ, Myers RM, Schmutz J, Dickson M, Grimwood J, Cox DR, Olson MV, Kaul R, Shimizu N, Kawasaki K, Minoshima S, Evans GA, Athanasiou M, Schultz R, Roe BA, Chen F, Pan H, Ramser J, Lehrach H, Reinhardt R, McCombie WR, de la Bastide M, Dedhia N, Blocker H, Hornischer K, Nordsiek G, Agarwala R, Aravind L, Bailey JA, Bateman A, Batzoglou S, Birney E, Bork P, Brown DG, Burge CB, Cerutti L, Chen HC, Church D, Clamp M, Copley RR, Doerks T, Eddy SR, Eichler EE, Furey TS, Galagan J, Gilbert JG, Harmon C, Hayashizaki Y, Haussler D, Hermjakob H, Hokamp K, Jang W, Johnson LS, Jones TA, Kasif S, Kaspryzk A, Kennedy S, Kent WJ, Kitts P, Koonin EV, Korf I, Kulp D, Lancet D, Lowe TM, McLysaght A, Mikkelsen T, Moran JV, Mulder N, Pollara VJ, Ponting CP, Schuler G, Schultz J, Slater G, Smit AF, Stupka E, Szustakowski J, Thierry-Mieg D, Thierry-Mieg J, Wagner L, Wallis J, Wheeler R, Williams A, Wolf YI, Wolfe KH, Yang SP, Yeh RF, Collins F, Guyer MS, Peterson J, Felsenfeld A, Wetterstrand KA, Patrinos A, Morgan MJ, Szustakowki J, de Jong P, Catanese JJ, Osoegawa K, Shizuya H, Choi S, Chen YJ: Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001, 409: 860-921. 10.1038/35057062.

Batzer MA, Deininger PL: A human-specific subfamily of Alu sequences. Genomics. 1991, 9: 481-487. 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90414-A.

Batzer MA, Gudi VA, Mena JC, Foltz DW, Herrera RJ, Deininger PL: Amplification dynamics of human-specific (HS) Alu family members. Nucleic Acids Research. 1991, 19: 3619-3623.

Batzer MA, Rubin CM, Hellmann-Blumberg U, Alegria-Hartman M, Leeflang EP, Stern JD, Bazan HA, Shaikh TH, Deininger PL, Schmid CW: Dispersion and insertion polymorphism in two small subfamilies of recently amplified human Alu repeats. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1995, 247: 418-427. 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0150.

Carroll ML, Roy-Engel AM, Nguyen SV, Salem AH, Vogel E, Vincent B, Myers J, Ahmad Z, Nguyen L, Sammarco M, Watkins WS, Henke J, Makalowski W, Jorde LB, Deininger PL, Batzer MA: Large-scale analysis of the Alu Ya5 and Yb8 subfamilies and their contribution to human genomic diversity. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2001, 311: 17-40. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4847.

Carter AB, Salem AH, Hedges DJ, Keegan CN, Kimball B, Walker JA, Watkins WS, Jorde LB, Batzer MA: Genome-wide analysis of the human Alu Yb-lineage. Human Genomics. 2004, 1: 167-178.

Xing JC, Salem AH, Hedges DJ, Kilroy GE, Watkins WS, Schienman JE, Stewart CB, Jurka J, Jorde LB, Batzer MA: Comprehensive analysis of two Alu Yd subfamilies. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 2003, 57: S76-S89. 10.1007/s00239-003-0009-0.

Xing J, Wang H, Han K, Ray DA, Huang CH, Chemnick LG, Stewart CB, Disotell TR, Ryder O, Batzer M: A Mobile Element Based Phylogeny of Old World Monkeys. Mol Phylogenet Evol.

Ray DA, Hedges DJ, Hall MA, Laborde ME, Anders BA, White BR, Stoilova N, Fowlkes JD, Landry KE, Chemnick LG, Ryder O, Batzer M: Alu Insertion Polymorphisms and Platyrrhine Primate Phylogenetic Relationships. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2005, 35: 117-126. 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.10.023.

Salem AH, Ray DA, Hedges DJ, Jurka J, Batzer MA: Analysis of the human Alu Ye lineage. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2005, 5: 18-10.1186/1471-2148-5-18.

Roy AM, Carroll ML, Nguyen SV, Salem AH, Oldridge M, Wilkie AO, Batzer MA, Deininger PL: Potential gene conversion and source genes for recently integrated Alu elements. Genome Research. 2000, 10: 1485-1495. 10.1101/gr.152300.

Garber RK, Hedges DJ, Herke SW, Hazard NW, Batzer MA: The Alu Yc1 subfamily: sorting the wheat from the chaff. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005, 110: 537-542. 10.1159/000084986.

Batzer MA, Deininger PL, Hellmann-Blumberg U, Jurka J, Labuda D, Rubin CM, Schmid CW, Zietkiewicz E, Zuckerkandl E: Standardized nomenclature for Alu repeats. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1996, 42: 3-6. 10.1007/BF00163204.

Kapitonov V, Jurka J: The age of Alu subfamilies. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1996, 42: 59-65. 10.1007/BF00163212.

Jurka J, Milosavljevic A: Reconstruction and analysis of human Alu genes. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1991, 32: 105-121.

Zietkiewicz E, Richer C, Labuda D: Phylogenetic affinities of tarsier in the context of primate Alu repeats. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 1999, 11: 77-83. 10.1006/mpev.1998.0564.

Shen MR, Batzer MA, Deininger PL: Evolution of the master Alu gene(s). Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1991, 33: 311-320. 10.1007/BF02102862.

DeBry RW, Olmstead RG: A simulation study of reduced tree-search effort in bootstrap resampling analysis. Systematic Biology. 2000, 49: 171-179. 10.1080/10635150050207465.

Goodman M, Porter CA, Czelusniak J, Page SL, Schneider H, Shoshani J, Gunnell G, Groves CP: Toward a phylogenetic classification of Primates based on DNA evidence complemented by fossil evidence. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 1998, 9: 585-598. 10.1006/mpev.1998.0495.

Smit AFA, Hubley R, Green P: Repeatmasker. [http://www.repeatmasker.org]

Bennett EA, Coleman LE, Tsui C, Pittard WS, Devine SE: Natural genetic variation caused by transposable elements in humans. Genetics. 2004, 168: 933-951. 10.1534/genetics.104.031757.

Johanning K, Stevenson CA, Oyeniran OO, Gozal YM, Roy-Engel AM, Jurka J, Deininger PL: Potential for retroposition by old Alu subfamilies. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 2003, 56: 658-664. 10.1007/s00239-002-2433-y.

Han K, Xing J, Wang H, Hedges DJ, Garber RK, Cordaux R, Batzer MA: Under the genomic radar: the stealth model of Alu amplification. Genome Research. 2005, 15: 655-664. 10.1101/gr.3492605.

Porter CA, Page SL, Czelusniak J, Schneider H, Schneider MPC, Sampaio I, Goodman M: Phylogeny and evolution of selected primates as determined by sequences of the e-globin locus and 5' flanking regions. International Journal of Primatology. 1997, 18: 261-295. 10.1023/A:1026328804319.

Schneider H, Schneider MP, Sampaio I, Harada ML, Stanhope M, Czelusniak J, Goodman M: Molecular phylogeny of the New World monkeys (Platyrrhini, primates). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 1993, 2: 225-242. 10.1006/mpev.1993.1022.

Kass DH, Batzer MA, Deininger PL: Gene conversion as a secondary mechanism of short interspersed element (SINE) evolution. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1995, 15: 19-25.

Wang J, Song L, Gonder MK, Azrak S, Ray DA, Batzer MA, Tishkoff SA, Liang P: Whole genome computational comparative genomics: a fruitful approach for ascertaining Alu insertion polymorphisms. GENE.

Schneider H, Sampaio I, Harada ML, Barroso CM, Schneider MP, Czelusniak J, Goodman M: Molecular phylogeny of the New World monkeys (Platyrrhini, primates) based on two unlinked nuclear genes: IRBP intron 1 and epsilon-globin sequences. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 1996, 100: 153-179. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199606)100:2<153::AID-AJPA1>3.0.CO;2-Z.

Schneider H: The current status of the New World monkey phylogeny. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias. 2000, 72: 165-172.

Singer SS, Schmitz J, Schwiegk C, Zischler H: Molecular cladistic markers in New World monkey phylogeny (Platyrrhini, Primates). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2003, 26: 490-501. 10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00312-3.

Steiper ME, Ruvolo M: New World monkey phylogeny based on X-linked G6PD DNA sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2003, 27: 121-130. 10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00375-5.

Porter CA, Czelusniak J, Schneider H, Schneider MP, Sampaio I, Goodman M: Sequences from the 5' flanking region of the epsilon-globin gene support the relationship of Callicebus with the pitheciins. American Journal of Primatology. 1999, 48: 69-75. 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1999)48:1<69::AID-AJP5>3.0.CO;2-1.

Porter CA, Czelusniak J, Schneider H, Schneider MP, Sampaio I, Goodman M: Sequences of the primate epsilon-globin gene: implications for systematics of the marmosets and other New World primates. GENE. 1997, 205: 59-71. 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00473-3.

Harada ML, Schneider H, Schneider MP, Sampaio I, Czelusniak J, Goodman M: DNA evidence on the phylogenetic systematics of New World monkeys: support for the sister-grouping of Cebus and Saimiri from two unlinked nuclear genes. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1995, 4: 331-349. 10.1006/mpev.1995.1029.

Canavez FC, Moreira MA, Ladasky JJ, Pissinatti A, Parham P, Seuanez HN: Molecular phylogeny of new world primates (Platyrrhini) based on beta2-microglobulin DNA sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1999, 12: 74-82. 10.1006/mpev.1998.0589.

Roy AM, Carroll ML, Kass DH, Nguyen SV, Salem AH, Batzer MA, Deininger PL: Recently integrated human Alu repeats: finding needles in the haystack. Genetica. 1999, 107: 149-161. 10.1023/A:1003941704138.

Bailey JA, Liu G, Eichler EE: An Alu transposition model for the origin and expansion of human segmental duplications. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2003, 73: 823-834. 10.1086/378594.

Callinan PA, Wang J, Herke SW, Garber RK, Liang P, Batzer MA: Alu retrotransposition-mediated deletion. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2005, 348: 791-800. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.043.

Hedges DJ, Callinan PA, R. Cordaux R, J. X, Barnes E, Batzer MA: Differential Alu mobilization and polymorphism among the human and chimpanzee lineages. Genome Research. 2004, 14: 1068-1075. 10.1101/gr.2530404.

Batzer MA, Arcot SS, Phinney JW, Alegria-Hartman M, Kass DH, Milligan SM, Kimpton C, Gill P, Hochmeister M, Ioannou PA, Herrera RJ, Boudreau DA, Scheer WD, Keats BJ, Deininger PL, Stoneking M: Genetic variation of recent Alu insertions in human populations. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1996, 42: 22-29. 10.1007/BF00163207.

Watkins WS, Rogers AR, Ostler CT, Wooding S, Bamshad MJ, Brassington AM, Carroll ML, Nguyen SV, Walker JA, Prasad BV, Reddy PG, Das PK, Batzer MA, Jorde LB: Genetic variation among world populations: inferences from 100 Alu insertion polymorphisms. Genome Research. 2003, 13: 1607-1618. 10.1101/gr.894603.

Watkins WS, Ricker CE, Bamshad MJ, Carroll ML, Nguyen SV, Batzer MA, Harpending HC, Rogers AR, Jorde LB: Patterns of ancestral human diversity: an analysis of Alu-insertion and restriction-site polymorphisms. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2001, 68: 738-752. 10.1086/318793.

Novick GE, Novick CC, Yunis J, Yunis E, Martinez K, Duncan GG, Troup GM, Deininger PL, Stoneking M, Batzer MA, Herrera RJ: Polymorphic human specific Alu insertions as markers for human identification. Electrophoresis. 1995, 16: 1596-1601. 10.1002/elps.11501601263.

Novick GE, Novick CC, Yunis J, Yunis E, Antunez de Mayolo P, Scheer WD, Deininger PL, Stoneking M, York DS, Batzer MA, Herrera RJ: Polymorphic Alu insertions and the Asian origin of Native American populations. Human Biology. 1998, 70: 23-39.

Dunn DS, Tait BD, Kulski JK: The distribution of polymorphic Alu insertions within the MHC class I HLA-B7 and HLA-B57 haplotypes. Immunogenetics. 2005, 56: 765-768. 10.1007/s00251-004-0745-3.

Romualdi C, Balding D, Nasidze IS, Risch G, Robichaux M, Sherry ST, Stoneking M, Batzer MA, Barbujani G: Patterns of human diversity, within and among continents, inferred from biallelic DNA polymorphisms. Genome Research. 2002, 12: 602-612. 10.1101/gr.214902.

de Pancorbo MM, Lopez-Martinez M, Martinez-Bouzas C, Castro A, Fernandez-Fernandez I, de Mayolo GA, de Mayolo AA, de Mayolo PA, Rowold DJ, Herrera RJ: The Basques according to polymorphic Alu insertions. Human Genetics. 2001, 109: 224-233. 10.1007/s004390100544.

Cotrim NH, Auricchio MT, Vicente JP, Otto PA, Mingroni-Netto RC: Polymorphic Alu insertions in six Brazilian African-derived populations. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2004, 16: 264-277.

Comas D, Calafell F, Benchemsi N, Helal A, Lefranc G, Stoneking M, Batzer MA, Bertranpetit J, Sajantila A: Alu insertion polymorphisms in NW Africa and the Iberian Peninsula: evidence for a strong genetic boundary through the Gibraltar Straits. Human Genetics. 2000, 107: 312-319. 10.1007/s004390000370.

Schmitz J, Zischler H: A novel family of tRNA-derived SINEs in the colugo and two new retrotransposable markers separating dermopterans from primates. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2003, 28: 341-349. 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00060-5.

Walker JA, Kilroy GE, Xing J, Shewale J, Sinha SK, Batzer MA: Human DNA quantitation using Alu element-based polymerase chain reaction. Analytical Biochemistry. 2003, 315: 122-128. 10.1016/S0003-2697(03)00081-2.

Walker JA, Hughes DA, Hedges DJ, Anders BA, Laborde ME, Shewale J, Sinha SK, Batzer MA: Quantitative PCR for DNA identification based on genome-specific interspersed repetitive elements. Genomics. 2004, 83: 518-527. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.09.003.

Walker JA, Hughes DA, Anders BA, Shewale J, Sinha SK, Batzer MA: Quantitative intra-short interspersed element PCR for species-specific DNA identification. Analytical Biochemistry. 2003, 316: 259-269. 10.1016/S0003-2697(03)00095-2.

Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP: MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003, 19: 1572-1574. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180.

Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F: MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001, 17: 754-755. 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754.

Swofford DL: PAUP: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods). 2002, , Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts, 4.0b10

Xing J, Hedges DJ, Han K, Wang H, Cordaux R, Batzer MA: Alu element mutation spectra: molecular clocks and the effect of DNA methylation. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2004, 344: 675-682. 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.058.

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Sen, J. Walker, M. Konkel, and S. Herke for comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health RO1 GM 59290 (MAB), National Science Foundation BCS-0218338 (MAB) and EPS-0346411 (MAB), and the State of Louisiana Board of Regents Support Fund (MAB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

DAR initiated the study, collected and aligned all of the sequences used in the project, performed all analyses, interpreted the data, and prepared the manuscript. MAB provided input on the analysis and interpretation of the data and on all versions of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12862_2005_163_MOESM1_ESM.txt

Additional File 1: Multiple sequence alignment of all Alu sequences used in this study. Clades of sequences described in the text are delimited and the newly described consensus sequences are included. (TXT 25 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ray, D.A., Batzer, M.A. Tracking Alu evolution in New World primates. BMC Evol Biol 5, 51 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-5-51

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-5-51