Abstract

Background

Alu elements are primate-specific retroposons that mobilize using the enzymatic machinery of L1 s. The recently completed baboon genome project found that the mobilization rate of Alu elements is higher than in the genome of any other primate studied thus far. However, the Alu subfamily structure present in and specific to baboons had not been examined yet.

Results

Here we report 129 Alu subfamilies that are propagating in the genome of the olive baboon, with 127 of these subfamilies being new and specific to the baboon lineage. We analyzed 233 Alu insertions in the genome of the olive baboon using locus specific polymerase chain reaction assays, covering 113 of the 129 subfamilies. The allele frequency data from these insertions show that none of the nine groups of subfamilies are nearing fixation in the lineage.

Conclusions

Many subfamilies of Alu elements are actively mobilizing throughout the baboon lineage, with most being specific to the baboon lineage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

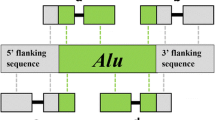

Alu elements are non-autonomous, non-long terminal repeat (non-LTR) retroposons found in high copy numbers in the genomes of primates [1, 2]. They consist of a left and right monomer separated by an A-rich middle linker region, along with an A-rich tail at the 3′ end of the element [3, 4]. These elements mobilize using proteins encoded by LINE-1 elements (L1 s), via a retrotransposition mechanism termed Target Primed Reverse Transcription (TPRT) [5, 6]. This mechanism allows for the creation of new copies of the element and for these copies to be inserted at novel locations in the genome (Reviewed in [1, 2, 7, 8]). Alu elements are short (approximately 300 base pairs (bp)), making them relatively easy to amplify and genotype via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and agarose gel electrophoresis. They have also been useful for phylogenetic and population genetics analyses, as they are nearly homoplasy free and the ancestral state of an element is known to be the absence of that insertion [9]. Hence, they have been used in a number of molecular studies over the last few decades [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25].

Alu elements can be broken down into subfamilies based on diagnostic mutations [26,27,28,29]. There are 3 major subfamilies of Alu elements: J, S, and Y [30]. These major subfamilies of Alu elements can be further expanded based on diagnostic mutations that they have accrued over millions of years [31]. Some subfamilies of elements can be shared within a number of closely related taxa, but other recent studies have identified elements that are unique to only a particular species or genus [15, 32]. This parallel evolution of Alu subfamilies results in each primate lineage having its own network of recently integrated Alu subfamilies [2]. The recent work of the Baboon Genome Analysis Consortium has revealed a great deal of information about the content of the baboon genome, including a much higher rate of AluY mobilization than seen in other primates (Rogers et al: The comparative genomics, epigenomics and complex population history of Papio baboons. In Preparation). Previous work on Alu elements in baboons has already been informative for population structure, species identification, and as a polymorphic marker for hybrid individuals in the field [33,34,35].

Baboons (genus Papio) are found throughout sub-Saharan Africa in distinct ranges with slight overlap. There are six species of baboons that are part of most recent studies, including: yellow baboon (Papio cynocephalus), olive baboon (Papio anubis), hamadryas baboon (Papio hamadryas), guinea baboon (Papio papio), chacma baboon (Papio ursinus), and the kinda baboon (Papio kindae). These six baboons are largely differentiated based on morphological differences (size, pelage coloration), as well as geographic range, dispersal, and social traits (Rogers et al: The comparative genomics, epigenomics and complex population history of Papio baboons. In Preparation) [36,37,38]. Though they differ in the above ways, many of these species are also known to be interfertile, with a number of studies examining their active hybrid zones [39,40,41,42,43]. Given their anatomical and physiological similarity to humans, baboons have been used for a number of medical studies, and have proven particularly valuable for cardiovascular studies [44,45,46]. In this study, due to the rapid mobilization of AluY elements in baboons reported in Rogers et al., and the recent utility of Alu elements for studies in baboons, we aimed to analyze the expansion of Alu subfamilies in the genome of the olive baboon, Papio anubis.

Methods

Ascertainment of baboon-specific Alu elements

Loci were ascertained by first using RepeatMasker [47] on the reference genome of the olive baboon, Papio anubis (Panu_2.0). Alu elements were parsed out of the resulting RepeatMasker file. The sequence of each full length (starts at or before position 4 in the element and ends after position 266) AluY insertion, along with 500 bases of flanking in 5′ and 3′ direction of the Alu element, was compared to the rhesus macaque (rheMac8) and human (hg19) reference genomes using BLAT [48]. We then compared the resulting BLAT files for any locus that had an appropriate gap size in the genomes that would indicate an insertion that was only present in the genome of the olive baboon.

COSEG analysis & network figure creation

Our Papio specific set of Alu elements was aligned to the AluY consensus sequence [49] using cross_match (http://www.phrap.org/phredphrapconsed.html; last accessed December 2017). The data set was then analyzed via COSEG (www.repeatmasker.org/COSEGDownload.html; last accessed November 2017) to determine subfamilies. The middle A-rich region of the AluY consensus sequence was omitted while tri and di segregating mutations were considered. Using these criteria, a set of ten or more identical sequences was considered an individual Alu subfamily. A network analysis of all subfamilies of Alu elements identified by COSEG was created by uploading the source and target subfamily information into Gephi (v0.9.1) [50].

Oligonucleotide primer design

Primers were designed using an in house Python script that utilized BLAT, MUSCLE (v3.8.31) [51], and a modified version of Primer3 [52]. Briefly, target sequences acquired from the genome of the reference olive baboon and orthologous sequences were found in human (hg19), chimpanzee (panTro4), and rhesus macaque (rheMac8) using BLAT. These sequences were then aligned using MUSCLE, and potential oligonucleotide primer locations were identified using Primer3. Oligonucleotide primers for PCR were ordered from Sigma Aldrich (Woodlands, TX). A complete list of PCR primers and genomic locations is available in Additional file 1 (worksheet “PCR Primer Information”).

Polymerase chain reaction assays

The PCR format and the DNA samples used for PCR assays are reported in Additional file 1 (worksheet “DNA panel”). We attempted to analyze at least 5 Alu insertions from each of the 9 main groups of Alu subfamilies in this report. PCR amplification was performed in 25 μL reactions that contained 25–50 ng of template DNA, 200 nM of each primer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10× PCR buffer, 0.2 mM deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates and 1 unit of Taq DNA polymerase. The PCR protocol is as follows: 95 °C for 1 min, 32 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, 30 s at a 57 °C annealing temperature, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, followed by a final extension step at 72 °C for 2 min. Gel electrophoresis was performed on a 2% agarose gel containing 0.2 μg/mL ethidium bromide for 60 min at 200 V. UV fluorescence was used to visualize the DNA fragments using a BioRad ChemiDoc XRS imaging system (Hercules, CA). Loci that did not amplify clearly were re-run using the JumpStart Taq DNA Polymerase kit from Sigma Aldrich.

Nucleotide model selection & tree design

The consensus sequence of each identified Alu subfamily was input into jModelTest-2.17 [53] for analysis and to determine the best model of nucleotide evolution for the data set. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) model selected was Trn + G, which includes variable base frequencies with equal transversion rates, but variable transition rates. The Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) selected was TrNef+G, which includes equal base frequencies, equal transversion rates, but variable transition rates.

The AIC model selected by jModelTest was input into PhyML [54], which was used to create the maximum likelihood tree, and the BIC model selected by jModelTest was input into BEAST (v2.4.6) [55], which was used to create the Bayesian tree. The TreeAnnotator program in BEAST was then used to summarize the information from the BEAST output, and FigTree (v1.4.3) (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/) was then used to visualize and create figures for both the maximum likelihood and Bayesian trees.

Results

COSEG analysis and alignment

In this study, through the use of python scripts and BLAT comparisons to the genomes of human and rhesus macaque, we ascertained and examined a total of 28,114 baboon-specific, full-length Alu element insertions. We used the genome of the rhesus macaque as an outgroup for comparison, as the Papio lineage diverged from the macaque lineage roughly 8 million years ago and our primary interest was finding elements that were unique to the genome of the baboon. Cross_match (see methods) was used for pairwise alignment, and these insertions were uploaded and analyzed by COSEG, producing 129 distinct Alu subfamilies for further investigation. The number of elements matching each consensus sequence produced by COSEG can be found in Additional file 1 (Worksheet “Subfamily Counts”). The consensus sequence for each of these 129 Alu subfamilies is available in Additional file 2. These subfamilies were uploaded into Gephi for visualization (Fig. 1 with a high resolution PDF available in Additional file 3). There are 9 major clusters of Alu elements (assigned a cluster number 1–9) that radiate from a single, central node (Subfamily 0) as shown in Fig. 1. Our subfamilies expand in a star-burst pattern, similar to bush-like shaped expansions of Alu elements previously reported [56]. It is important to note that the subfamily names assigned by the COSEG output are random, and not numerically ordered to be indicative of the network of source and offspring elements.

Network analysis of the COSEG assigned subfamilies, with each identified subfamily as a single node. Related subfamilies are clustered together, are connected by lines, and all branch out from the central node (labeled Cluster 1, shown in purple). Line length between subfamilies is not indicative of number of mutations or evolutionary time between subfamilies

To determine if the subfamilies were novel, we aligned the consensus sequences of the subfamilies that were produced by COSEG with one another and to Alu elements from RepBase [49] using MUSCLE (Fig. 2, and complete alignment in Additional file 2). The resulting MUSCLE output was visualized in BioEdit [57] to determine if these subfamilies were novel or had been previously discovered. We found that 127 of 129 subfamilies were newly discovered in this study, with only two of these subfamilies that had been previously identified. Subfamily 70 aligned to the consensus sequence of AluY, and Subfamily 0 aligned with the consensus sequence of AluMacYa3, previously discovered in the genome of the rhesus macaque and reported in Repbase (Smit, A. F. AluMacYa3-SINE1 SINE from Macaca. Direct submission to Repbase Update (06-Sep-2005)). The central subfamily for Clusters 2, 3, and 4 (as numbered in Fig. 1) were aligned, along with the central subfamily for Cluster 7, 8, and 9 (Fig. 2). As the clusters radiate outward from Cluster 1, they accrue more mutations, allowing for the visualization of subfamily specific evolution.

Alignment of consensus sequence for Alu subfamilies positioned in the central node of radiating clusters illustrated in Fig. 1. a. Alignment of central subfamilies from Clusters 2, 3, and 4. This alignment shows the accumulation of diagnostic mutations that have occurred over time. Subfamily 41 (Cluster 3) acquired new mutations when compared to Subfamily 32 (Cluster 2), and Subfamily 42 (Cluster 4) shares diagnostic mutations with Subfamily 41 while acquiring additional mutations. b. Alignment of central subfamilies from Clusters 7, 8, and 9 showing a similar acquisition of diagnostic mutations over time. Subfamily 16 (Cluster 8) acquired mutations when compared to Subfamily 3 (Cluster 7), and Subfamily 17 (Cluster 9) continued to acquire mutations when compared to Subfamily 16

In order to confirm our computational findings, we designed oligonucleotide primers using an in-house Python script and analyzed 233 young (< 2% diverged from the consensus sequence) insertions through locus specific PCR and gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3). With these 233 assays, we were able to confirm the presence of 113 of our 127 (89%) novel subfamilies. We also successfully amplified at least five insertions from each of the nine major clusters shown in Fig. 1. The 14 subfamilies that were not successfully PCR validated were reviewed and we found that these loci were in repeat-rich genomic regions, limiting the effectiveness of these particular assays. Detailed information for each locus examined, as well as primer information and allele frequency data can be found in Additional file 1 (worksheets “PCR Primer Information” and “Genotypes”).

a. Agarose gel chromatograph of a polymorphic, olive baboon-specific Alu insertion (found at chr3:168089568–168,090,568; primer information can be found in Additional file 1 (Worksheet “PCR Primer Information”)). Each lane of the gel is labeled at the top of the image. The filled (insertion present) (~ 590 bp) site is seen only in the reference olive baboon individual (lane 4), and empty (insertion absent) sites (~ 275 bp) are seen in all other individuals. b. Agarose gel chromatograph of a polymorphic, Papio-specific Alu insertion (found at chr4:144885392–144,886,392; primer information can be found in Additional file 1 (Worksheet “PCR Primer Information”)). The empty site is found in lane 3 (HeLa, human control), lanes 7 and 8 (chacma baboons), lane 11 and 12 (kinda baboons), lane 14 (one yellow baboon), and lanes 16 and 17 (gelada baboons). The filled site can be seen in lanes 4–6 (olive baboons), 9 and 10 (guinea baboons), lane 13 (one yellow baboon), and lane 15 (hamadryas baboon). A list of DNA samples is available in Additional file 1, worksheet “DNA panel”

Full length Alu elements from each of the 9 clusters were identified and examined for divergence from the consensus sequence. We found a total of 19,888 full length elements that were classified by RepeatMasker to be members of novel subfamilies discovered in this study. 12,800 (~ 64%) of these Alu repeats were determined to be less than 2% diverged from their respective consensus sequence (Table 1). Elements that are less than 2% diverged from their consensus sequence are considered to be relatively young, as they have not accrued many mutations since their insertion [58, 59]. The percentage of elements less than 2% diverged from their consensus sequence varies from cluster to cluster, and though the sample size of elements that were analyzed by PCR was modest for some of the clusters, the allele frequency among the individuals of genus Papio for each cluster was far from fixation, ranging from ~ 40% to ~ 66% (Table 1).

jModelTest-2.17 was used to determine the best nucleotide model for creating a phylogenetic tree. Following the best model selected by jModelTest, we created both a Bayesian tree, using the BIC model chosen by jModelTest (Fig. 4 with a high resolution PDF available in Additional file 4), and a maximum likelihood tree using the AIC model chosen by jModelTest (Additional file 5). Both trees were rooted using subfamily 70, which was found to match the consensus sequence of AluY. The maximum likelihood tree shows many unresolved relationships between subfamilies; however, the general grouping of subfamilies is similar to those observed in Fig. 1. The Bayesian tree is more resolved and displays a defined branching pattern between all subfamilies. The Bayesian tree also displays subfamily relationships that are highly similar to the relationships determined by COSEG displayed in Fig. 1. Based on the Bayesian tree and alignments, we were able to determine the relative radiation of our Alu subfamilies and their possible derivatives.

Bayesian tree created in BEAST, showing the relationship between subfamilies. The tree was rooted using the AluY consensus sequence (Subfamily 70). Each branch is colored based on the color of the cluster shown in Fig. 1 that the subfamily belongs to

Discussion

The results of this study show an ongoing expansion of Alu elements in the Papio lineage, with more novel recently integrated subfamilies of Alu elements present than in any other previously analyzed human or non-human primate genome [15, 32, 60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. For comparison, only 14 lineage-specific Alu subfamilies were found in the genome of the rhesus macaque [61], and 46 Saimiri-specific Alu subfamilies were found in a recent analysis [32]. The 127 novel Alu subfamilies present in the baboon lineage supports the results of the Baboon Genome Analysis Consortium, which showed that the baboon lineage has undergone a rapid expansion of Alu elements (Rogers et al: The comparative genomics, epigenomics and complex population history of Papio baboons. In Preparation). Recent work also supports that the expansion of Alu elements is not unique to the olive baboon, but rather the Papio lineage as a whole [33, 35].

Of the nine clusters and 127 novel Alu subfamilies reported here, all of the elements (Fig. 1) appear to be derived from subfamilies discovered in the genome of Rhesus macaque [61]. The central subfamily of Cluster 1, which was determined to match the consensus sequence of AluMacYa3, seems to be the source or parent to a large number of closely related subfamilies. All of the members of Cluster 6 are also very closely related to AluMacYa3, showing only a small number of insertions or deletions near and moving into the middle A-rich region of the element. The central nodes of Cluster 2, 3, and 4, (subfamily 32, 41, and 42, respectively), as well as the surrounding, related subfamilies, all appear to be derived from Alu YRa1 [61]. The central nodes of Clusters 7, 8, and 9 (subfamily 3, 16, and 17, respectively) show a similar pattern, as they are likely derived from AluYRa4 [61]. The apparent origin of these elements is not surprising given that the Papio lineage diverged from the macaca lineage roughly 8 million years ago (mya) (Rogers et al: The comparative genomics, epigenomics and complex population history of Papio baboons. In Preparation) Interestingly, the subfamilies present in Cluster 5 are similar to the AluYc (originally named Yd) [69] element present in humans, and the AluYRb [61] family from the genome of Rhesus macaque. Each subfamily present in Cluster 5 (as well as the previously known similar elements in human and rhesus) shares the same 12 bp deletion in the left monomer of the element, supporting the prolonged activity and evolution of these closely related Alu subfamilies through multiple lineages [69].

All of the elements in our study expand out from a central subfamily, subfamily 0, originally found in the genome of the Rhesus macaque. The novel elements in our study follow the star-like or bush-like pattern of evolution (Fig. 1) as seen in a number of previous studies of Alu subfamily structure [56]. The expansion seen in these nine clusters supports the intermediate master gene model or stealth model, with multiple active elements leading to the expansion of new subfamilies (see Clusters 2–4, and Clusters 7–9) [56, 70]. The elements uncovered by this study appear to be quite young, with the majority of the full-length representatives of our novel subfamilies being under 2% diverged from their respective consensus sequences (see Table 1). The allele frequencies for polymorphic elements in each cluster also reflects this, as none of the clusters of closely related subfamilies appear to have reached fixation for the presence of the Alu element (Table 1) based on our small panel of Papio individuals (Additional file 1). The rapid radiation/expansion of genus Papio, which occurred only ~ 2.5 mya, likely contributes to this lack of allele fixation, along with gene flow from troop migration and hybridization occurring along active hybrid zones (Rogers et al: The comparative genomics, epigenomics and complex population history of Papio baboons. In Preparation) [33].

The Bayesian phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 4) largely supports the relationships displayed in the network analysis of COSEG results. However, it is important to note that the relationships shown in the network analysis reflect what COSEG has determined to be source and offspring elements, not phylogenetic relationships. Discrepancies between the phylogenetic tree and the network analysis are likely the result of two elements showing closer sequence identity, even if they did not come from the same “parent” node of the network analysis.

The recent findings of the Baboon Genome Analysis Consortium, along with other recent studies of mobile elements in the baboon genome have provided a great deal of new information (Rogers et al: The comparative genomics, epigenomics and complex population history of Papio baboons. In Preparation) [33, 35]. This study found 127 novel Alu element subfamilies, supporting the high Alu mobilization rate reported by the Baboon Genome Analysis Consortium (Rogers et al: The comparative genomics, epigenomics and complex population history of Papio baboons. In Preparation). It is important to note, however, that these elements are considered to be lineage-specific based on the genomic information currently available. Additionally, it is unlikely that the Alu elements uncovered in this study represent the loss of a particular element from the human or rhesus macaque genome as the precise deletion of an element is an exceedingly rare event [9]. As the number of sequenced primate genomes grows, and as sequencing quality continues to improve, it’s likely that new subfamilies may be discovered or that some of these newly reported subfamilies may be found in other closely related species. Future studies should attempt to determine underlying causes of rapid mobilization of transposable elements within the lineage. This increased duplication rate may extend to mobilization competent “master” elements including L1, or it may be caused by decreased activity of host defenses that have been shown to slow activity in humans [71,72,73].

Conclusions

Overall, we identified 129 Alu subfamilies that were active in Papio baboons, with 127 of these insertions being baboon specific. This work reinforces that there has been extensive expansion of Alu elements and subfamilies within genus Papio.

Abbreviations

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criterion

- BIC:

-

Bayesian information criterion

- Bp:

-

Base pairs

- L1:

-

Long interspersed element-1

- MYA:

-

Million years ago

- TPRT:

-

Target primed reverse transcription

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

References

Cordaux R, Batzer MA. The impact of retrotransposons on human genome evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(10):691–703.

Konkel MK, Walker JA, Batzer MA. LINEs and SINEs of primate evolution. Evol Anthropol. 2010;19(6):236–49.

Deininger P. Alu elements: know the SINEs. Genome Biol. 2011;12(12):236.

Jurka J, Zuckerkandl E. Free left arms as precursor molecules in the evolution of Alu sequences. J Mol Evol. 1991;33(1):49–56.

Dewannieux M, Esnault C, Heidmann T. LINE-mediated retrotransposition of marked Alu sequences. Nat Genet. 2003;35(1):41–8.

Luan DD, Korman MH, Jakubczak JL, Eickbush TH. Reverse transcription of R2Bm RNA is primed by a nick at the chromosomal target site: a mechanism for non-LTR retrotransposition. Cell. 1993;72(4):595–605.

Batzer MA, Deininger PL. Alu repeats and human genomic diversity. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3(5):370–9.

Levin HL, Moran JV. Dynamic interactions between transposable elements and their hosts. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(9):615–27.

Ray DA, Xing J, Salem AH, Batzer MA. SINEs of a nearly perfect character. Syst Biol. 2006;55(6):928–35.

Batzer MA, Stoneking M, Alegria-Hartman M, Bazan H, Kass DH, Shaikh TH, Novick GE, Ioannou PA, Scheer WD, Herrera RJ, et al. African origin of human-specific polymorphic Alu insertions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(25):12288–92.

Hamdi H, Nishio H, Zielinski R, Dugaiczyk A. Origin and phylogenetic distribution of Alu DNA repeats: irreversible events in the evolution of primates. J Mol Biol. 1999;289(4):861–71.

Hartig G, Churakov G, Warren WC, Brosius J, Makalowski W, Schmitz J. Retrophylogenomics place tarsiers on the evolutionary branch of anthropoids. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1756.

Kriegs JO, Churakov G, Jurka J, Brosius J, Schmitz J. Evolutionary history of 7SL RNA-derived SINEs in Supraprimates. Trends Genet. 2007;23(4):158–61.

Li J, Han K, Xing J, Kim HS, Rogers J, Ryder OA, Disotell T, Yue B, Batzer MA. Phylogeny of the macaques (Cercopithecidae: Macaca) based on Alu elements. Gene. 2009;448(2):242–9.

McLain AT, Carman GW, Fullerton ML, Beckstrom TO, Gensler W, Meyer TJ, Faulk C, Batzer MA. Analysis of western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) specific Alu repeats. Mob DNA. 2013;4(1):26.

Meyer TJ, McLain AT, Oldenburg JM, Faulk C, Bourgeois MG, Conlin EM, Mootnick AR, de Jong PJ, Roos C, Carbone L, et al. An Alu-based phylogeny of gibbons (hylobatidae). Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29(11):3441–50.

Ray DA, Walker JA, Hall A, Llewellyn B, Ballantyne J, Christian AT, Turteltaub K, Batzer MA. Inference of human geographic origins using Alu insertion polymorphisms. Forensic Sci Int. 2005;153(2–3):117–24.

Ray DA, Xing J, Hedges DJ, Hall MA, Laborde ME, Anders BA, White BR, Stoilova N, Fowlkes JD, Landry KE, et al. Alu insertion loci and platyrrhine primate phylogeny. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2005;35(1):117–26.

Roos C, Schmitz J, Zischler H. Primate jumping genes elucidate strepsirrhine phylogeny. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(29):10650–4.

Salem AH, Ray DA, Xing J, Callinan PA, Myers JS, Hedges DJ, Garber RK, Witherspoon DJ, Jorde LB, Batzer MA. Alu elements and hominid phylogenetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(22):12787–91.

Schmitz J, Ohme M, Zischler H. SINE insertions in cladistic analyses and the phylogenetic affiliations of Tarsius bancanus to other primates. Genetics. 2001;157(2):777–84.

Witherspoon DJ, Marchani EE, Watkins WS, Ostler CT, Wooding SP, Anders BA, Fowlkes JD, Boissinot S, Furano AV, Ray DA, et al. Human population genetic structure and diversity inferred from polymorphic L1(LINE-1) and Alu insertions. Hum Hered. 2006;62(1):30–46.

Watkins WS, Rogers AR, Ostler CT, Wooding S, Bamshad MJ, Brassington A-ME, Carroll ML, Nguyen SV, Walker JA, Prasad BVR, et al. Genetic variation among world populations: inferences from 100 Alu insertion polymorphisms. Genome Res. 2003;13(7):1607–18.

Watkins WS, Ricker CE, Bamshad MJ, Carroll ML, Nguyen SV, Batzer MA, Harpending HC, Rogers AR, Jorde LB. Patterns of ancestral human diversity: an analysis of Alu-insertion and restriction-site polymorphisms. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68(3):738–52.

Stoneking M, Fontius JJ, Clifford SL, Soodyall H, Arcot SS, Saha N, Jenkins T, Tahir MA, Deininger PL, Batzer MA. Alu insertion polymorphisms and human evolution: evidence for a larger population size in Africa. Genome Res. 1997;7(11):1061–71.

Britten RJ, Baron WF, Stout DB, Davidson EH. Sources and evolution of human Alu repeated sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(13):4770–4.

Jurka J, Smith T. A fundamental division in the Alu family of repeated sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(13):4775–8.

Slagel V, Flemington E, Traina-Dorge V, Bradshaw H, Deininger P. Clustering and subfamily relationships of the Alu family in the human genome. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4(1):19–29.

Willard C, Nguyen HT, Schmid CW. Existence of at least three distinct Alu subfamilies. J Mol Evol. 1987;26(3):180–6.

Batzer MA, Deininger PL, Hellmann-Blumberg U, Jurka J, Labuda D, Rubin CM, Schmid CW, Zietkiewicz E, Zuckerkandl E. Standardized nomenclature for Alu repeats. J Mol Evol. 1996;42(1):3–6.

Deininger PL, Batzer MA, Hutchison CA 3rd, Edgell MH. Master genes in mammalian repetitive DNA amplification. Trends Genet. 1992;8(9):307–11.

Baker JN, Walker JA, Vanchiere JA, Phillippe KR, St. Romain CP, Gonzalez-Quiroga P, Denham MW, Mierl JR, Konkel MK, Batzer MA. Evolution of Alu subfamily structure in the Saimiri lineage of new world monkeys. Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9(9):2365–76.

Steely CJ, Walker JA, Jordan VE, Beckstrom TO, CL MD, St. Romain CP, Bennett EC, Robichaux A, Clement BN, Raveendran M, et al. Alu insertion polymorphisms as evidence for population structure in baboons. Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9(9):2418–27.

Szmulewicz MN, Andino LM, Reategui EP, Woolley-Barker T, Jolly CJ, Disotell TR, Herrera RJ. An Alu insertion polymorphism in a baboon hybrid zone. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1999;109(1):1–8.

Walker JA, Jordan VE, Steely CJ, Beckstrom TO, McDaniel CL, St. Romain CP, Bennett EC, Robichaux A, Clement BN, Konkel MK, et al. Papio baboon species indicative Alu elements. Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9(6):1788–96.

Charpentier MJ, Tung J, Altmann J, Alberts SC. Age at maturity in wild baboons: genetic, environmental and demographic influences. Mol Ecol. 2008;17(8):2026–40.

Fischer J, Kopp GH, Dal Pesco F, Goffe A, Hammerschmidt K, Kalbitzer U, Klapproth M, Maciej P, Ndao I, Patzelt A, et al. Charting the neglected west: the social system of Guinea baboons. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2017;162:15–31.

Swedell L, Saunders J, Schreier A, Davis B, Tesfaye T, Pines M. Female “dispersal” in hamadryas baboons: transfer among social units in a multilevel society. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2011;145(3):360–70.

Alberts SC, Altmann J. Immigration and hybridization patterns of yellow and anubis baboons in and around Amboseli, Kenya. Am J Primatol. 2001;53:139.

Charpentier MJ, Fontaine MC, Cherel E, Renoult JP, Jenkins T, Benoit L, Barthes N, Alberts SC, Tung J. Genetic structure in a dynamic baboon hybrid zone corroborates behavioural observations in a hybrid population. Mol Ecol. 2012;21(3):715–31.

Jolly CJ, Burrell AS, Phillips-Conroy JE, Bergey C, Rogers J. Kinda baboons (Papio kindae) and grayfoot chacma baboons (P. ursinus griseipes) hybridize in the Kafue river valley, Zambia. Am J Primatol. 2011;73(3):291–303.

Jolly CJ, Woolley-Barker T, Beyene S, Disotell TR, Phillips-Conroy JE. Intergeneric hybrid baboons. Int J Primatol. 1997;18:597-627.

Maples W, McKern T. A preliminary report on classification of the Kenya baboon. Baboon Med Res. 1967;2:13–22.

Cox LA, Comuzzie AG, Havill LM, Karere GM, Spradling KD, Mahaney MC, Nathanielsz PW, Nicolella DP, Shade RE, Voruganti S, et al. Baboons as a model to study genetics and epigenetics of human disease. ILAR J. 2013;54(2):106–21.

Premawardhana U, Adams MR, Birrell A, Yue DK, Celermajer DS. Cardiovascular structure and function in baboons with type 1 diabetes -- a transvenous ultrasound study. J Diabetes Complicat. 2001;15(4):174–80.

Yeung KR, Chiu CL, Pears S, Heffernan SJ, Makris A, Hennessy A, Lind JM. A cross-sectional study of ageing and cardiovascular function over the baboon lifespan. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159576.

RepeatMasker Open-4.0 [http://www.repeatmasker.org].

Kent WJ. BLAT--the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12(4):656–64.

Jurka J, Kapitonov VV, Pavlicek A, Klonowski P, Kohany O, Walichiewicz J. Repbase update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110(1–4):462–7.

Bastian M, Heymann S, Jacomy M. Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. 2009.

Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792–7.

Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M, Rozen SG. Primer3--new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(15):e115.

Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods. 2012;9:772.

Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59(3):307–21.

Bouckaert R, Heled J, Kühnert D, Vaughan T, Wu C-H, Xie D, Suchard MA, Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. BEAST 2: a software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10(4):e1003537.

Cordaux R, Hedges DJ, Batzer MA. Retrotransposition of Alu elements: how many sources? Trends Genet. 2004;20(10):464–7.

Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for windows 95/98/NT. Nucl Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95-98.

Bennett EA, Keller H, Mills RE, Schmidt S, Moran JV, Weichenrieder O, Devine SE. Active Alu retrotransposons in the human genome. Genome Res. 2008;18(12):1875–83.

Konkel MK, Walker JA, Hotard AB, Ranck MC, Fontenot CC, Storer J, Stewart C, Marth GT, Batzer MA. Sequence analysis and characterization of active human Alu subfamilies based on the 1000 genomes pilot project. Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7(9):2608–22.

The Marmoset Genome Sequencing and Analysis Consortium. The common marmoset genome provides insight into primate biology and evolution. Nat Genet. 2014;46:850.

Han K, Konkel MK, Xing J, Wang H, Lee J, Meyer TJ, Huang CT, Sandifer E, Hebert K, Barnes EW, et al. Mobile DNA in old world monkeys: a glimpse through the rhesus macaque genome. Science. 2007;316(5822):238–40.

Stewart C, Kural D, Stromberg MP, Walker JA, Konkel MK, Stutz AM, Urban AE, Grubert F, Lam HY, Lee WP, et al. A comprehensive map of mobile element insertion polymorphisms in humans. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(8):e1002236.

Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409(6822):860–921.

Warren WC, Jasinska AJ, García-Pérez R, Svardal H, Tomlinson C, Rocchi M, Archidiacono N, Capozzi O, Minx P, Montague MJ, et al. The genome of the vervet (Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus). Genome Res. 2015;25(12):1921–33.

Locke DP, Hillier LW, Warren WC, Worley KC, Nazareth LV, Muzny DM, Yang S-P, Wang Z, Chinwalla AT, Minx P, et al. Comparative and demographic analysis of orang-utan genomes. Nature. 2011;469:529.

Carbone L, Alan Harris R, Gnerre S, Veeramah KR, Lorente-Galdos B, Huddleston J, Meyer TJ, Herrero J, Roos C, Aken B, et al. Gibbon genome and the fast karyotype evolution of small apes. Nature. 2014;513:195.

Gibbs RA, Rogers J, Katze MG, Bumgarner R, Weinstock GM, Mardis ER, Remington KA, Strausberg RL, Venter JC, Wilson RK, et al. Evolutionary and biomedical insights from the rhesus macaque genome. Science. 2007;316(5822):222–34.

The Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium. Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:69.

Xing J, Salem A-H, Hedges DJ, Kilroy GE, Scott Watkins W, Schienman JE, Stewart C-B, Jurka J, Jorde LB, Batzer MA. Comprehensive analysis of two Alu Yd subfamilies. J Mol Evol. 2003;57(1):S76–89.

Han K, Xing J, Wang H, Hedges DJ, Garber RK, Cordaux R, Batzer MA. Under the genomic radar: the stealth model of Alu amplification. Genome Res. 2005;15(5):655–64.

Hulme AE, Bogerd HP, Cullen BR, Moran JV. Selective inhibition of Alu retrotransposition by APOBEC3G. Gene. 2007;390(1–2):199–205.

Jacobs FMJ, Greenberg D, Nguyen N, Haeussler M, Ewing AD, Katzman S, Paten B, Salama SR, Haussler D. An evolutionary arms race between KRAB zinc-finger genes ZNF91/93 and SVA/L1 retrotransposons. Nature. 2014;516:242.

Wolf G, Yang P, Füchtbauer AC, Füchtbauer E-M, Silva AM, Park C, Wu W, Nielsen AL, Pedersen FS, Macfarlan TS. The KRAB zinc finger protein ZFP809 is required to initiate epigenetic silencing of endogenous retroviruses. Genes Dev. 2015;29(5):538–54.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the members of the Batzer lab for their help with experiments and constructive criticism of the manuscript. We would also like to thank the Baboon Genome Analysis Consortium for the hard work contributing to these experiments. Members are listed in Additional file 6.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 GM59290 (MAB).

Availability of data and materials

All DNA samples, genotype, allele frequency, consensus sequence, divergence percentages, and alignment data are available as part of the Additional files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

CJS and JNB performed analysis of the baboon genome, subfamily analysis, and phylogenetic analysis and created the resulting figures. CJS designed primers and CJS and CDLIII performed PCR and gel electrophoresis/imaging. CJS and JNB wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JAW and MAB contributed to experimental design, and final edits to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

“Not applicable”.

Consent for publication

“Not applicable”.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

An excel file containing different worksheets for DNA samples and PCR format, PCR primers and genomic locations of amplified insertions, subfamily counts, and genotype data with allele frequency for each locus. (XLSX 78 kb)

Additional file 2:

An alignment file of Alu subfamily consensus sequences. (FAS 114 kb)

Additional file 3:

Higher resolution PDF of Fig. 1. (PDF 39 kb)

Additional file 4:

Higher resolution PDF of Fig. 4. (PDF 16 kb)

Additional file 5:

Maximum likelihood tree using the AIC model determined by jModelTest-2.17. (PNG 238 kb)

Additional file 6:

List of the members of the Baboon Genome Analysis Consortium. (DOC 13 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Steely, C.J., Baker, J.N., Walker, J.A. et al. Analysis of lineage-specific Alu subfamilies in the genome of the olive baboon, Papio anubis. Mobile DNA 9, 10 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13100-018-0115-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13100-018-0115-6