Abstract

Groundwater acts as a lifeline in the coastal regions to meet out the domestic, drinking, irrigational and industrial needs. To investigate the hydrogeochemical characteristics of groundwater and its suitability, twenty samples were collected from the shallow tubewells of study area having screen depth 21–54 m. The water quality assessment has been carried out by evaluating the physicochemical parameters such as temperature, pH, EC, TDS and major ions i.e., Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl−, SO4 2−, NO3 −, HCO3 −. Results found that, the water is slightly alkaline and brackish in nature. The trends of cations and anions are Na+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+ > K+ and Cl− > HCO3 − > SO4 2− > NO3 −, respectively and Na–Cl–HCO3 is the dominant groundwater type. The analyzed samples were also characterized with different indices, diagram and permissible limit i.e., electric conductivity (EC), total dissolved solids (TDS), chloride content (Cl), soluble sodium percentage (SSP), sodium adsorption ratio (SAR), residual sodium carbonate (RSC), magnesium adsorption ratio (MAR), Kelley’s ratio (KR), Wilcox diagram and USSL diagram, and results showed that groundwater are not suitable for drinking and irrigational use. The factors responsible for the geochemical characterization were also attempted by using standard plot and it was found that mixing of seawater with entrapped water plays a significant role in the study area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Groundwater is the most important source of domestic, industrial and agricultural water supply in the world. It is estimated that approximately one third of the world’s population use groundwater for drinking purpose (Nickson et al. 2005). It is found in aquifers that have the capacity of both storing and transmitting water, in significant quantities (Todd 1980). Generally, groundwater quality depends on the quality of recharged water, atmospheric precipitation, inland surface water and subsurface geochemical processes (Twarakavi and Kaluarachchi 2006; Kumar et al. 2014). In coastal regions groundwater quality patterns are complex, because of the input from different water sources including precipitation, seawater, ascending deep groundwater and anthropogenic sources (Steinich et al. 1998). Problems in coastal areas are typically connected to contamination of fresh water resources by saline water and include well field salinization, crop damage, and surface water quality deterioration (Karro et al. 2004).

Bangladesh lies in the northeastern part of South Asia, has 710 km coastal line and the coastal area covers about 32% of the country (MoWR 2005). Although, coastal aquifers serve as major sources of freshwater supply, the groundwater in coastal region is relatively vulnerable to contamination by seawater intrusion, which makes groundwater unsuitable (Kim et al. 2006; Jorgensen et al. 2008). Natural processes and anthropogenic activities like; over extraction, urbanization and agricultural activities are the main reason for seawater intrusion and water quality deterioration in coastal aquifers (Mondal et al. 2011; Selvam et al. 2013). Nowadays, almost 53% of the coastal areas of Bangladesh are affected by salinity (Hoque et al. 2003; Woobaidullah et al. 2006; Islam 2014). Salinity becomes a major problem in south-western coastal region of Bangladesh, where irrigation water quality is affected by high levels of salinity (Shammi et al. 2016a), which is a source of irrigation salinity and it mainly results from rises in the groundwater table due to excessive irrigation and the lack of adequate drainage for leaching and removal of salts (Corwin et al. 2007). The total area under irrigation in Bangladesh is 5,049,785 ha and 78.9% of this area is covered by groundwater sources including 3,197,184 ha with 1,304,973 shallow tubewells and 785,680 ha with 31,302 deep tubewells (DPHE and JICA 2010). However, most crop lands in the coastal areas of Bangladesh remain fallow in the dry season because surface water resources are saline and unsuitable for irrigation, while groundwater is not intensively utilized because of the fear of seawater intrusion into aquifers (Mondal et al. 2008). Seawater intrusion is a major threat in the coastal aquifers of Bangladesh, especially in southwestern region (Bahar and Reza 2010; Islam et al. 2015, 2016b; Islam and Bhuiyan 2016). The over dependence on groundwater for drinking, agricultural and industrial sector and different climatic and natural phenomenon causes coastal groundwater contamination (Srinivas et al. 2015). Besides, different geochemical processes in groundwater governing the chemical characteristics of groundwater, is well documented in many parts of the world by many authors i.e., Montety et al. (2008), Jalali (2009), Manjusree et al. (2009), Thilagavathi et al. (2012), Sivasubramanian et al. (2013), Nagaraju et al. (2014), Kumar et al. (2015), Islam et al. (2016a, b) and Balaji et al. (2016). Geochemical studies of groundwater provide a better understanding of water quality and possible changes (Kumar et al. 2014). However, the coastal groundwater system is fragile and its evaluation will help in the proper planning and sustainable management (Sefie et al. 2015). Therefore detailed investigations regarding the groundwater hydrogeochemistry and water quality in shallow aquifer is imperative. So the present study aims to investigate the groundwater, to determine its utility and find out the major geochemical process in study area. It also intended to delineate the spatial distribution of hydrogeochemical constituents for proper understanding and future management perspective.

Study area

Location and hydrological setting

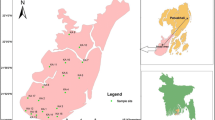

Geographically, the study area is located between 22º28′ and 22º56′ N latitudes and between 89º12′ and 89º40′ E longitudes (Fig. 1). The investigated area falls within the western part of Faridpur Trough of Bengal Foredeep (Alam 1990) and is located on a natural levee of the Rupsha and Bhairab rivers and characterized by Ganges tidal floodplains with low relief, criss-crossed by rivers and water channels, and surrounded by tidal marshes and swamps. The surface lithology of the area is of deltaic deposits which are composed of tidal deltaic deposits, deltaic silt deposits, and mangrove swamp deposits (Alam 1990). The aquifers in and around the study area are generally multi-layered varying from unconfined to leaky-confined in the shallow alluvial deposits and confined in the deeper alluvial deposits (Uddin and Lundberg 1998). The aquifer systems of the study area can be classified into two major classes: the shallow aquifers ranging from depth ~10 to 150 m and deep aquifers generally >180 m depth are shown in Fig. 2. The water of this aquifer is generally brackish or saline with few isolated fresh water pockets (DPHE 2006).

Weather and climate

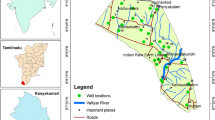

Climate is one of the most important factors for the occurrence and movement of groundwater (CGW Board 2009; Islam et al. 2016b). The study area falls in the south-central zone, south-western and south-eastern zone of the climatic sub-division (Fig. 3) and with bulk of rainfall occurring between the months of June to October, high temperature and excessive humidity (BMD 2014). The area comprise of three major climatic seasons includes hot summer (March–May), followed by monsoon or rainy season (June–October) and a moderate winter season (November–February). Analyzing the rainfall data from 1993 to 2012 it is observed that maximum rainfall occurs during the rainy season May to October with the peak occurring in July while during the dry period there is almost no rainfall (Iftakher et al. 2015). The mean annual rainfall of Khulna district is approximately 1816 mm. and the mean temperature is 34 °C (BMD 2014). Besides, many others natural phenomenon storm surge, tidal flood and salinity are very common in this area (Ahmed 2006; Islam and Uddin 2015; Islam et al. 2015).

Map showing the climatic zones of Bangladesh (Rashid 1991)

Materials and methods

Field sampling and water analysis

A total 20 groundwater samples were collected from different locations of the study area (Fig. 1) from shallow tubewells. Most of the sampled wells were fitted with a standard Bangladesh number-6 hand pump. Prior to sampling each well were pumped for few minutes until it purged out approximately twice the well volume, or until steady state chemical conditions (pH, EC and temperature) were obtained. pH of the water samples were measured on spot by using pH meter (EcoScan Ion-6, Singapore); total dissolved solids (TDS) were measured by (HANNA HI8734, Romania) portable meter. Electric conductivity (EC) and salinity were measured by portable EC meter (HANNA HI8033, Romania). Temperature was also measured simultaneously by using the same TDS meter. The geographical location of each wells were determined with a GARMIN handheld global positioning system (GPS) and the approximate depth of wells were noted from the well owner’s records. Samples for major ion (Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl–, SO4 2–, NO3 – and HCO3 −) analysis were collected in 500 mL polyethylene bottles. Each bottle was rinsed with distilled water before pouring the sample water. The bottles were labeled and air-tight. Two sets of samples were collected from each location and filtered through 0.45 μm cellulose nitrate hydrophilic syringe filters. Among them one was acidified using concentrated HNO3 to reach a pH <2 for preventing absorption and chemical precipitation. For ion analysis Gallenkamp Flame Analyzer was used for Na+ and K+ and, ICS-5000 DIONEX SP, ion chromatography (IC) for Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl−, SO4 2−, and NO3 − analysis. Samples were diluted several times and the relative standard deviation of measured major ions was found to be within ±3%. Alkalinity (HCO3 −) was measured by titration method with Digital Titrator (16900, HACH International, Colorado, USA) and 1.6 N H2SO4 cartridge.

Methods for hydrogeochemical and water quality evaluation

To assess water quality and geochemical processes the following parameters were calculated:

The total hardness (TH) in ppm (Todd 1980; Ragunath 1987; Hem 1991) was determined by following equation:

Soluble sodium percentage (SSP) or Na % was used to evaluate the sodium hazard. Todd (1980) defined soluble sodium percentage (SSP) or Na % as:

To evaluate the water quality for irrigation purpose, the sodium or alkali hazard expressed by sodium adsorption ratio (SAR) is widely used (Bhuiyan et al. 2015; Islam et al. 2016a, b). If water sample is high in Na+ and low in Ca2+, the ion exchange complex may become saturated with Na+ which destroys the soil structure (Todd 1980). The SAR value of irrigation water quantifies the relative proportion of Na+ to Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Alrajhi et al. 2015), and is computed as:

where, Na+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ are defined as the concentrations of Na, Ca and Mg ions in water, respectively (Ayers and Westcot 1985).

The residual sodium carbonate (RSC) is computed taking the alkaline earths and weak acids as follows (Ragunath 1987; Rao et al. 2012);

Magnesium adsorption ratio (MAR) (Ragunath 1987), also known as magnesium hazard (MH) was calculated as:

Lastly, Kelley’s ratio (KR) (Kelley 1963) described as:

All ionic concentrations are in milli equivalent per liter (meq/L). All these parameters and individual chemical parameters had been compared with national and international standards to assess the groundwater suitability.

Moreover, to identify the water types using major ion compositions AquaChem (version 3.7) software was used. SPSS (version 16.00) was used to statistical correlation among anion and cation of the groundwater samples and the spatial analysis were carried out using Arc. GIS (version 10.1) software.

Results and discussion

General hydrochemistry

The results of various hydrochemical parameters of groundwater samples are presented in Table 1. The depths of the sampled wells varied from 21 to 54 m. The pH of water is slightly alkaline ranging from 6.5 to 7.9 with a mean value of 7.2. The pH indicates the strength of the water to react with the acidic or alkaline material presents in water, which controls by the CO2, CO3 2− and HCO3 − concentrations (Hem 1991). The mean temperature of groundwater samples was 26.7 °C ranging from 26 to 27.3 °C. Electrical conductivity (EC) of groundwater depends upon temperature, ionic concentration and types of ions present in the water. The maximum permissible limit of EC in groundwater is 1500 µS/cm (WHO 2011) where electrical conductivity (EC) of study area ranging from 498 to 5910 μS/cm with a mean value of 3018.65 μS/cm. The total dissolved solids (TDS) values range from 237 to 3112 mg/L with a mean of 1556.05 mg/L. Fetter (2001) stated that TDS values of groundwater within the range of 1000–10,000 mg/L are considered as brackish water and most of the groundwater samples in study area are falls on this group.

Concentrations of Na+ show extremely wide range from 13.18 to 1212.61 mg/L with a mean of 647.20 mg/L, which constitute 77% of total cations (Fig. 4a). Ca2+ is the second dominant cation in groundwater constituting 18% with mean value 101.5 mg/L. The average Mg2+ concentration in groundwater is 78.28 mg/L constitutes 9% of total cation. Meanwhile, K+ constitutes the least concentrations in all observed ground waters and forms 2% with a mean of 17.05 mg/L. The trend of major cationic concentrations of groundwater samples are Na+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+ > K+.

The groundwater is of Cl− dominant range from 32.07 to 6270.8 mg/L. The mean chloride concentration is 1776.74 mg/L constitute 77% of total anionic compositions of collected groundwater samples in study area (Fig. 4b), where WHO limit for chloride in groundwater is <250 mg/L (WHO 2004). Surprisingly, 19 out of 20 samples were exceeds the WHO limit of chloride concentrations. Followed by, HCO3 − concentrations range from 261 to 808 mg/L with mean value of 510.05 mg/L that makes up 22% of total anions and remaining SO4 2− (mean 4.97 mg/L) and NO3 − (mean 2.61 mg/L) concentrations are very low as compared to other parameters (Fig. 4b). The anionic trend of groundwater is Cl− > HCO3 − > SO4 2− > NO3 −.

The results of the water quality from the study area are compared with previous study in others coastal areas of Bangladesh and standard permissible limit in Table 2. It was found that, all the parameters of water are much higher than others study in coastal areas of Bangladesh and also deep aquifer water. This indicates that, shallow aquifer of the coastal area is more vulnerable. It was also found that, most of the water quality parameters exceed the standard permissible limit for drinking and irrigational use (Table 2).

From the Pearson correlation matrix of hydrochemical parameters in groundwater (Table 3), it has been seen that EC and TDS are negatively correlated with pH but strongly correlated with Na+ and Cl−. EC and TDS are closely related with each other. Na+ shows positive correlation with all variables but, strongly correlated with Cl−, Ca2+ and Mg2+. K+ and Mg2+ are correlated with each other but show negative correlation with NO3 −. Both have strong correlation with Ca2+ and Cl−. Except pH, Ca2+ showed positive correlation with each variable but strongly related with Cl−. Cl− has strong correlation with EC, TDS, Na+ and Mg2+ and SO4 2− has strong correlation with groundwater pH, which indicates that they originate from the same source or origin.

Hydrogeochemical classification of groundwater

Hydrochemical facies and water type

The values obtained from the groundwater samples were plotted by using Piper (1953) trilinear diagram (Fig. 5) to recognize the hydrochemical facies which are able to provide clues how groundwater quality changes within and between aquifers (Sivasubramanian et al. 2013). This diagram is also used to classify the water types (Wen et al. 2005), which are generally distinct zones that cation and anion concentrations are described within the defined composition categories. From the samples plotting on the Piper (1953), trilinear diagram (Fig. 5) reveals that four types; Na–Cl (35%), Na–Cl–HCO3 (55%), Na–Mg–Cl (5%) and Ca–Mg–Cl (5%) and Na–Cl–HCO3 are the predominant facies type (Table 4). It indicates the dominance of Na+ in the cations and interplays of HCO3 − and Cl− in anions and also influence of marine water in the study area.

Piper (1953) diagram for the groundwater samples of the study area

TDS, EC and Cl2 content in relation groundwater salinity

Salinity is the dissolved salt content of a body of water. It used to describe the levels of different salts such as sodium chloride, magnesium and calcium sulfates and bicarbonates. The amount of chlorine is directly proportional to salinity, which originates from the dissociation of salts, such as sodium chloride or calcium chloride, in water.

These salts and their resulting chloride ions originate from natural minerals and mixing of seawater with fresh water (Stuyfzand 1999). Although there are some small quantities of others ions (K+, Mg+, SO4 2−, NO3 −); Na+ and Cl− present about 91% of all seawater ions. Meanwhile, Sodium and total dissolved solids (TDS) are other important parameters that can be used to observe the influence of major components and groundwater salinity. The groundwater concentrations of Na+ and Cl− were plotted against TDS. The plot showed that most Na+ and Cl− ions of the groundwater were positively correlated (r 2 = 0.75 and 0.76, respectively) with TDS (Fig. 6a, b). According to WHO (2004) classification of groundwater based on TDS, 60% sample falls in unacceptable, 35% poor and only 5% falls in excellent category and the spatial distribution of TDS is shown in Fig. 7. All others component i.e., Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+ and K+ also well correlated with Cl− with r 2 values 0.82, 0.79, 0.78 and 0.58 respectively (Fig. 6c–f) denotes they are originated from same sources.

According to Chloride classification by Stuyfzand (1989) 60% groundwater sample falls in brackish-salt, 35% brackish and remaining 5% falls in fresh category (Table 4). Spatial distribution of chloride concentration in groundwater shows that, the eastern and southern site of study area considered as higher saline prone area compared to northwestern site (Fig. 8). EC is other important parameters that are related with groundwater salinity. In order to diagnosis and classification, the total concentration of soluble salts (salinity hazard) in water can be expressed in terms of specific conductance (Ravikumar et al. 2011). According to WHO (2004) salinity hazard based on EC value has been classified as four groups; low salinity hazard, medium salinity hazard, high salinity hazard and very high salinity hazard. This reveals that, 5% medium, 15% high, 70% very high and remaining 10% are extremely high salinity hazard. Wilcox (1955) was also drawn classification of EC as excellent, good, permissible, doubtful and poor categories. Studies show that, 5% falls in excellent, 15% good, 70% doubtful and remaining 10% poor category. The spatial distribution of groundwater shows high EC values in eastern and southern part of the study area ranges from 2300 to 5910 μS/cm along the bank of Rupsha river like; Boitaghata and Rupsha upazila (Fig. 9) possibly due to the infiltration and saline water intrusion from the river.

Total hardness (TH)

Hardness is an important criterion for determining the suitability of groundwater for domestic, agricultural and industrial uses (Vandenbohede et al. 2010). Hardness of water is related to its reaction with soap and to the scale of incrustation accumulating in containers or conducts where water is heated or transported. Since soap is precipitated by Ca2+ and Mg2+ ion. It is defined as the sum of concentration of their ion expressed an mg/L of CaCO3. The classification of the groundwater of the study area based on hardness (Sawyer and McCarthy 1967) has been carried out and is presented in Table 4. Accordingly, 9 samples (45%) fall under the hard and 11 samples (55%) fall in very hard category.

Soluble sodium percentage (SSP) or Na%

Sodium is an important cation, which in excess deteriorates the soil structure and reduces crop yield (Srinivasamoorthy et al. 2005). The ratio of sodium and potassium in the sum of cation is the important factor in considering water for agriculture uses. The sodium concentration of irrigation water is of prime importance and plays a significant role in determining the permeability of soil. Na+ absorbed on clay surface, as a substitute for Ca2+ and Mg2+ may damage the soil structure making it compact and impervious (Singh et al. 2008). Percentage of Na+ content is a parameter to assess its suitability for agriculture purpose (Wilcox 1948) as, sodium combining with CO3 2− can add to the formation of alkaline soils and sodium combining with Cl− form saline soils. Both these soils do not helping growth of plants. According to Wilcox (1955) maximum 15% of Na+ in groundwater is allowed for agriculture purpose, 45% samples fall in doubtful region and remaining 40% is unsuitable category (Table 4). Eaton (1950) classification also results same assumption. The plot of Na % against EC Wilcox (1955) diagram shows the suitability of groundwater samples are shown in Fig. 10.

Wilcox (1955) diagram for the study area

Sodium absorption ratio (SAR)

Sodium absorption ratio (SAR) is an estimate of the extent to which sodium ion present in the water would be absorbed by the soil. The higher the SAR value, the greater the risk of sodium hazard on plant growth. Irrigation, using water with high SAR values may require soil amendments to prevent long-term damage to the soil; because the sodium in the water can displace the calcium and magnesium in the soil. This will cause a decrease in the ability of the soil to form stable aggregates and loss of soil structure. This will also lead to a decrease in infiltration and permeability of the soil to water, leading to problems with crop production (Chandrasekar et al. 2013). SAR values ranged from 0.35 to 15.78 in study area (Table 1). Values greater than 2.0 indicate groundwater is unsuitable for irrigation purposes (Vasanthavigar et al. 2010; Ayuba et al. 2013; Islam et al. 2016b). Study shows that, except one sample all the sample falls in unsuitable category (Table 4). Salinity and SAR determines the utility of groundwater. Salinity originates in groundwater due to weathering of rocks and leaching from top soil, anthropogenic sources along with minor influence on climate (Prasanna et al. 2011). The level of Na+ and HCO3 − in irrigation groundwater affects permeability of soil and drainage of the area (Tijani 1994). US salinity laboratory’s (USSL) diagram proposed by Richards (1954) is used to investigate the sampled groundwater, which shows that, maximum samples fall on medium to very high salinity hazard (Fig. 11). The distribution of SAR values in the study area is shown in Fig. 12. It is observed that samples of low SAR are mainly located in the north-eastern part of the area, while high SAR dominated the southern and western part of study area.

Sample water classification for irrigation according to US Salinity Laboratory’s (USSL) diagram (Richards 1954)

Residual sodium carbonate (RSC)

A relation of alkaline earths with weak acids is expressed in terms of RSC for assessing the quality of water for irrigation (Richards 1954). When the weak acids are greater than the alkaline earths, a precipitation of alkaline earths occurs in soils, which damages the permeability of soil (Rao et al. 2012). The water having excess of carbonate and bicarbonate cover the alkaline earth mainly Ca2+ and Mg2+ in excess of allowable limits affects agriculture unfavorably (Richards 1954). The variation of RSC was drawn using (Richards 1954) as good, medium and bad categories. Study shows that, 65% groundwater samples of the study area fall in good category, 20% medium and remaining 15% falls in bad category (Table 4). Spatial analysis showed that there is no significant variation of RSC distribution in studied samples. The lowest value of RSC was found in the northeastern part of the study area (Fig. 13).

Magnesium adsorption ratio (MAR)

Magnesium adsorption ratio (MAR) defines the relationship between magnesium and calcium concentration in groundwater (Ragunath 1987; Ayuba et al. 2013). The excess Mg2+ affects the quality of soil resulting in poor agricultural returns (Islam et al. 2016a, b). Soil containing high levels of exchangeable Mg2+ causes infiltration problem (Ayers and Westcot 1985). MAR greater than 50 is considered harmful and unsuitable for irrigation purposes (Kacmaz and Nakoman 2010; Islam et al. 2016b). About 70% of the studied water falls in this category and remaining 30% falls in suitable category in case of magnesium hazard (Table 4).

Kelley’s ratio (KR)

The level of Na+ measured against Ca2+ and Mg2+ is known as Kelley’s Ratio, based on which irrigation water can be rated (Kelley 1963). Concentration of Na+ in irrigation water is considered to be in excess, thereby making the water unsuitable, if Kelley’s ratio is >1. Hence water with Kelley’s ratio <1 is suitable for irrigation. Almost 95% water in the study area is unsuitable according to this category (Table 4). From the above investigation, it is evident that the groundwater of the study area is not suitable for drinking or irrigation purpose.

Hydrogeochemical process evaluation

A hydrogeochemical diagram proposed by Chadha (1999) has been applied in this study to identify the hydrochemical process. The same procedure was successfully applied by (Vandenbohede et al. 2010; Islam et al. 2016b) in coastal aquifer to determine the evolution of different hydrogeochemical processes within a freshwater lens. For that, data was converted to percentage reaction values (milli equivalent percentages) and expressed as the difference between alkaline earths (Ca2+ + Mg2+) and alkali metals (Na+ + K+) for cations, and the difference between weak acidic anions (HCO3 − + CO3 2−) and strong acidic anions (Cl− + SO 24 ). The hydrochemical processes suggested by Chadha (1999) are indicated in each of the four quadrants of graph. These are broadly summarized as:

Field 1 Ca-HCO3 type recharging water.

Field 2 Ca–Mg–Cl type reverse ion exchange water.

Field 3 Na–Cl type end member waters (seawater).

Field 4 Na-HCO3 type base ion exchange water.

The resultant diagram is exhibited in (Fig. 14). Field 1 (recharging water) when water enters into the ground from the surface it carries dissolved carbonate in the form of HCO3 − and the geochemically mobile Ca2+. Only one sample falls in this field are represented by low salinity waters. Field 2 (reverse ion exchange) it may represent groundwater where Ca2++ Mg2+ is in excess to Na++ K+ either due to the preferential release of Ca2+ and Mg2+ from mineral weathering of exposed bedrock, or possibly reverse base cation exchange reactions of Ca2++ Mg2+ into solution and subsequent adsorption of Na+ onto mineral surfaces. But, there is no sample falls in this field. Most of the samples falls in Field 3 (Na–Cl) waters is typical of seawater mixing, and Field 4 (Na-HCO3) waters represent base-exchange reactions, but surprisingly no sample falls in this field. From this it is clear that, the water quality of coastal area containing high Na+ and Cl− with typical seawater mixing in Field 3 and with no representation in Field 2 and Field 4 indicating the absence of ion exchange.

However, when seawater intrudes into fresh coastal aquifer, CaCl2 or MgCl2 type water may found (Appelo and Postma 1999). In this case, Na+ of seawater is being replaced with either Ca2+ or Mg2+ of the clay minerals whereby, Na+ is being adsorbed onto the clay mineral surface according to Eqs. (9) and (10) (Islam et al. 2016b).

where, X signifies the exchanger. So, seawater intrusion is not the fact of salinization in the study area. When seawater diluted with freshwater have create distinguished geochemical characteristics (Metcafe and Eddy 2000). Modification of the geochemical characteristics of these saline waters is caused by water–rock interaction in which three possible mechanisms may be involved: (1) base exchange reactions with clay minerals (Vengosh et al. 1994); (2) adsorption onto clay minerals and (3) carbonate dissolution-precipitation (Vengosh et al. 1994; Ghabayen et al. 2006).

Actually, the sea level in the Bengal Basin has been changed from the past (CEGIS 2006). During the holocene period, about 6 Ka is the peak period of the last highest sea level (DPHE 2006). The earliest Ganges delta development phase took place about 5–2.5 Ka (Allison et al. 2003). Majumder (2008) observed that the age of the deep groundwater fell along the seawater line ranged from nearly ~6 to 25 Ka. So it seems that, brackish water originated from the sea is trapped within the aquifer. The salinity of current study originates from this saline aquifer pocket with some recent intrusion. Similar observation was previously made by Sikdar et al. (2001), Rahman et al. (2011) and Islam et al. (2016a, b). Due to lack of isotopic investigation it is hurdle to delineate the actual origin of groundwater salinity in study area. But, it is clear that, shallow aquifer salinity enhances due to tidal surges and cyclone, water logging, upstream less water flow, backwater effect, shrimp culture and excess withdrawal (Islam 2014; Islam and Bhuiyan 2016).

Conclusion

The study reveals that the shallow groundwater aquifers of the study area are strongly affected by salinity. EC and TDS classification indicate majority of the samples grouped within “doubtful” to “unsuitable” with minor representation in permissible category. In SSP or Na % classification of groundwater for irrigation purposes, majority of the samples grouped in unsafe zone and minor representations also falls in safe zone. The plot of Na % against EC (Wilcox diagram) also shows that, maximum samples are doubtful to unsuitable for irrigation purpose. According to chloride classification majority of samples grouped in brackish and brackish-salt category, indicating the unsuitability of this water for agricultural activity. The ground water of this region shows chiefly in seawater characters, and few represent recharge. From spatial distribution of chloride, TDS, EC, SAR and RSC concentrations of collected groundwater, northwestern part is better than eastern and southern part of the study area which is nearer to the river channel and the coast.

References

Ahmed AU (2006) Bangladesh climate change impacts and vulnerability. Comprehensive Disaster Management Programme (CDMP), Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh

Ahmed MJ, Haque MR, Rahman MM (2011) Physicochemical assessment of surface and groundwater resources of Noakhali region of Bangladesh. Int J Chem Sci Technol 1(1):1–10

Alam M (1990) Bangladesh in world regional geology. Columbia University Press, New York

Allison MA, Goodbred SL Jr, Kuehl SA, Khan SR (2003) Stratigraphic evolution of the late holocene Ganges–Brahmaputra lower delta plain. Sediment Geol 155:317–342

Alrajhi A, Beecham S, Bolan NS, Hassanli A (2015) Evaluation of soil chemical properties irrigated with recycled wastewater under partial root-zone drying irrigation for sustainable tomato production. Agric Water Manag 161:127–135. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2015.07.013

Appelo CAJ, Postma D (1999) Chemical analysis of groundwater, geochemistry, groundwater and pollution. Balkema, Rotterdam

Ayers RS, Westcot DW (1985) Water quality for agriculture, FAO irrigation and drainage Paper 29. Rev. I, UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome

Ayuba R, Omonona OV, Onwuka OS (2013) Assessment of groundwater quality of Lokoja Basement Area, North-Central Nigeria. J Geol Soc India 82:413–420

Bahar MM, Reza MS (2010) Hydrochemical characteristics and quality assessment of shallow groundwater in a coastal area of Southwest Bangladesh. Environ Earth Sci 61(5):1065–1073. doi:10.1007/s12665-009-0427-4

Balaji E, Nagaraju A, Sreedhar Y, Thejaswi A, Sharifi Z (2016) Hydrochemical characterization of groundwater in around Tirupati area, Chittoor District, Andhra Pradesh, South India. Appl Water Sci. doi:10.1007/s13201-016-0448-6

Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD) (2014) Government of the Peoples Republic of Bangladesh, Dhaka

Bhuiyan MAH, Ganyaglo S, Suzuki S (2015) Reconnaissance on the suitability of the available water resources for irrigation in Thakurgaon District of northwestern Bangladesh. Appl Water Sci 5(3):229–239. doi:10.1007/s13201-014-0184-8

Bhuiyan MAH, Bodrud-Doza M, Islam ARMT, Rakib MA, Rahman MS, Ramanathan AL (2016) Assessment of groundwater quality of Lakshimpur district of Bangladesh using water quality indices, geostatistical methods, and multivariate analysis. Environ Earth Sci. doi:10.1007/s12665-016-5823-y

BWPCB (1976) Bangladesh drinking water standard. Bangladesh Water Pollution Control Board, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Dhaka

CEGIS (2006) Final report of impact of sea level rise on land use suitability and adaptation options in southwest region of Bangladesh. Center for Environmental and Geographic Information Services (CEGIS), Dhaka

Central Ground Water (CGW) Board (2009) Report: south eastern coastal region, Chennai, India

Chadha DK (1999) A proposed new diagram for geochemical classification of natural waters and interpretation of chemical data. Hydrol J 7(5):431–439

Chandrasekar N, Selvakumar S, Srinivas Y, John Wilson JS, Simon Peter T, Magesh NS (2013) Hydrogeochemical assessment of groundwater quality along the coastal aquifers of southern Tamil Nadu, India. J Environ Earth Sci 71(11):4739–4750. doi:10.1007/s12665-013-2864-3

Corwin DL, Rhoades JD, Šimůnek J (2007) Leaching requirement for soil salinity control: steady-state versus transient models. Agric Water Manag 90(3):165–180. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2007.02.007

DPHE (2006) Final report on development of deep aquifer database and preliminary deep aquifer map (First Phase), Department of Public Health Engineering, Local Government Division, Ministry of LGRD and Co-operatives, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh

DPHE (Department of Public Health Engineering)/JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) (2010) Situation analysis of arsenic mitigation 2009. Department of Public Health Engineering, Dhaka, p 29

Eaton EM (1950) Significance of carbonate in irrigation water. Soil Sci 69:123–133

FAO (1985) Water quality for agriculture. Food and Agriculture Organization. http://www.fao.org/docrep/003/t0234e/T0234E01.htm#ch1.4. Accessed 21 Dec 2013

Fetter CW (2001) Applied hydrogeology, 4th edn. Prentice Hall Inc., New Jersey, p 598

Ghabayen MS, Mac McKee, Mariush Kemblowski (2006) Ionic and isotopic ratios for identification of salinity sources and missing data in the Gaza aquifer. J Hydrol 318:360–373

Hem JD (1991) Study and interpretation of the chemical characteristics of natural waters, 3rd edn. Book 2254. Scientific Publishers, Jodhpur

Hoque M, Hasan MK, Ravenscroft P (2003) Investigation of groundwater salinity and gas problems in southeast Bangladesh. In: Rahman AA, Ravenscroft P (eds) Groundwater resources and development in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies (BCAS), University Press Ltd, Dhaka

Iftakher A, Saiful IM, Jahangir AM (2015) Probable origin of salinity in the shallow aquifers of khulna district, southwestern Bangladesh. Austin J Earth Sci 2(2):1–8

Islam SMD (2014) Geoelectrical and hydrogeochemical studies for delineating seawater intrusion in coastal aquifers of Kalapara upazila, Patuakhali, Bangladesh. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Department of Environmental Sciences, Jahangirnagar University, Dhaka

Islam SMD, Bhuiyan MAH (2016) Impact scenarios of shrimp farming in coastal region of Bangladesh: an approach of an ecological model for sustainable management. Aquacult Int 24(4):1163–1190. doi:10.1007/s10499-016-9978-z

Islam SMD, Uddin MJ (2015) Impacts, vulnerability and coping with cyclone hazard in coastal region of Bangladesh: a case study on Kalapara upazila of Patuakhali district. Jahangirnagar Univ Environ Bull 4:11–30

Islam SMD, Bhuiyan MAH, Ramanathan AL (2015) Climate change impacts and vulnerability assessment in coastal region of bangladesh: a case study on Shyamnagar upazila of Satkhira district. J Climate Change 1(1–2):37–45. doi:10.3233/JCC-150003

Islam MA, Zahid A, Rahman MM, Rahman MS, Islam MJ, Akter Y, Shammi M, Bodrud-Doza M, Roy B (2016a) Investigation of groundwater quality and its suitability for drinking and agricultural use in the south central part of the coastal region in Bangladesh. Expo Health. doi:10.1007/s12403-016-0220-z

Islam SMD, Majumder RK, Uddin MJ, Khalil MI, Alam MF (2016b) Hydrochemical characteristics and quality assessment of groundwater in patuakhali district, southern coastal region of Bangladesh. Expo Health. doi:10.1007/s12403-016-0221-y

IWM (2009) Final report: hydro-geological study and mathematical modelling to identify sites for installation of observation well nests, selection of model boundary, supervision of pumping test, slug test, assessment of different hydro-geological parameters collection and conduct chemical analysis of surface water and groundwater. Dhaka, Bangladesh

Jalali M (2009) Geochemistry characterization of groundwater in an agricultural area of Razan, Hamadan, Iran. Environ Geol 56:1479–1488

Jorgensen NO, Andersen MS, Engesgaard P (2008) Investigation of a dynamic seawater intrusion event using strontium isotopes (87Sr/86Sr). J Hydrol 348:257–269

Kacmaz H, Nakoman ME (2010) Hydrochemical characteristics of shallow groundwater aquifer containing Uranyl phosphate minerals in the Koprubasi (Manisa) area, Turkey. Environ Earth Sci 59:449–457

Karro E, Marandi A, Vaikm R (2004) The origin of increased salinity in the Cambrian–Vendian aquifer system on the Kopl Peninsula, northern Estonia. Hydrogeol J 12:424–435

Kelley WP (1963) Use of saline irrigation water. Soil Sci 95:355–391

Kim RH, Kim JH, Ryu JS, Chang HW (2006) Salinization properties of a shallow groundwater in a coastal reclaimed area, Yeonggwang, Korea. Envion Geol 49:1180–1194

Kumar SK, Bharani R, Magesh NS, Godson PS, Chandrasekar N (2014) Hydrogeochemistry and groundwater quality appraisal of part of south Chennai coastal aquifers, Tamil Nadu, India using WQI and fuzzy logic method. Appl Water Sci 4:341–350. doi:10.1007/s13201-013-0148-4

Kumar SK, Logeshkumaran A, Magesh NS, Godson PS, Chandrasekar N (2015) Hydro-geochemistry and application of water quality index (WQI) for groundwater quality assessment, Anna Nagar, part of Chennai City, Tamil Nadu, India. Appl Water Sci 5:335–343. doi:10.1007/s13201-014-0196-4

Majumder RK (2008) Groundwater flow system studies in Bengal Delta, Bangladesh revealed by environmental isotopes and hydrochemistry. In: Proceedings of 36th IAH Congress, October 2008, Toyama, Japan

Manjusree TM, Joseph S, Thomas J (2009) Hydrogeochemistry and groundwater quality in the coastal sandy clay aquifers of alappuzha district, kerala. J Geol Soc India 74:459–468

Metcafe, Eddy (2000) Integrated aquifer management plan: final report. Gaza Coastal Aquifer Management Program, USAID Contract No. 294-C-00-99-00038-00

Mondal MK, Tuong TP and Sattar MA (2008) Quality and groundwater level dynamics at two coastal sites of Bangladesh: implications for irrigation development, 2nd International Program on Water and Food, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, November 10–14. https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/3707/IFWF2_proceedings_Volume%20II.pdf?sequence=1

Mondal NC, Singh VP, Singh VS (2011) Hydrochemical characteristic of coastal aquifer from Tuticorin, Tamilnadu, India. Environ Monit Assess 175:531–550

Montety VD, Radakovitch O, Vallet-Coulomb C, Blavoux B, Hermitte D, Valles V (2008) Origin of groundwater salinity and hydrogeochemical processes in a confined coastal aquifer: case of the Rhône delta (Southern France). Appl Geochem 23:2337–2349

MoWR (2005) Coastal Zone Policy (CZPo), Ministry of Water Resources (MoWR), Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Dhaka

Nagaraju A, Sunil Kumar K, Thejaswi A (2014) Assessment of groundwater quality for irrigation: a case study from Bandalamottu lead mining area, Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh, South India. Appl Water Sci 4:385–396. doi:10.1007/s13201-014-0154-1

Nickson RT, McArthur JM, Shresthn B, Kyaw- Nyint TO, Lowry D (2005) Arsenic and other drinking water quality issues, Muzaffargarh District, Pakistan. Appl Geochem 20(1):55–66

Piper AM (1953) A graphic procedure I the geo-chemical interpretation of water analysis, USGS Groundwater Note no, 12

Prasanna MV, Chidambaram S, Gireesh TV, Jabir Ali TV (2011) A study on hydrochemical characteristics of surface and subsurface water in and around Perumal Lake, Cuddalore District, Tamil Nadu, South India. Environ Earth Sci 64(5):1419–1431

Ragunath HM (1987) Groundwater. Wiley Eastern, New Delhi, p 563

Rahman ATMT, Majumder RK, Rahman SH, Halim MA (2011) Sources of deep groundwater salinity in the southwestern zone of Bangladesh. Environ Earth Sci 63:363–373. doi:10.1007/s12665-010-0707-z

Rao NS, Subrahmanyam A, Kumar SR, Srinivasulu N, Rao GB, Rao PS, Reddy GV (2012) Geochemistry and quality of groundwater of Gummanampadu sub-basin, Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh, India. Environ Earth Sci 67(5):1451–1471

Rashid H (1991) Geography of Bangladesh, 2nd edn. University Press, Dhaka

Ravikumar P, Somashekar RK, Angami M (2011) Hydrochemistry and evaluation of groundwater suitability for irrigation and drinking purposes in the Markandeya River basin, Belgaum District, Karnataka State, India. Environ Monit Assess 173(1–4):459–487

Richards LA (1954) Diagnosis and improvement of saline and alkali soils, vol 60. US Department of Agricultural Handbook, Washington D.C., p 160

Sawyer GN, McCarthy DL (1967) Chemistry of sanitary engineers, 2nd edn. McGraw Hill, New York, p 518

Sefie A, Aris AZ, Shamsuddin MKN, Tawnie I, Suratman S, Idris AN, Saadudin SB, Ahmed WKW (2015) Hydrogeochemistry of groundwater from different aquifer in Lower Kelantan Basin, Kelantan, Malaysia. International Conference on Environmental Forensics 2015. Procedia Environ Sci 30:151–156

Selvam S, Manimaran G, Sivasubramanian P (2013) Hydrochemical characteristics and GIS-based assessment of groundwater quality in the coastal aquifers of Tuticorin corporation, Tamilnadu, India. Appl Water Sci 3:145–159

Shammi M, Karmakar B, Rahman MM, Islam MS, Rahman R, Uddin MK (2016a) Assessment of salinity hazard of irrigation water quality in monsoon season of Batiaghata Upazila, Khulna District, Bangladesh and adaptation strategies. Pollution 2(2):183–197

Shammi M, Rahman R, Rahman MM, Moniruzzaman M, Bodrud-Doza M, Karmakar B, Uddin MK (2016b) Assessment of salinity hazard in existing water resources for irrigation and potentiality of conjunctive uses: a case report from Gopalganj District, Bangladesh. Sustain Water Resour Manag. doi:10.1007/s40899-016-0064-5

Sikdar PK, Sarkar SS, Palchoudhury S (2001) Geochemical evolution of groundwater in the quaternary aquifer of Calcutta and Howrah, India. J Asian Earth Sci 19:579–594

Singh AK, Mondal GC, Kumaar S, Sinngh TB, Sinha A (2008) Major ion chemistry, weathering processes and water quality assessment in upper catchment of Damodar River basin, India. Environ Geol 54:745–758

Sivasubramanian P, Balasubramanian N, Soundranayagam JP, Chandrasekar N (2013) Hydrochemical characteristics of coastal aquifers of Kadaladi, Ramanathapuram District, Tamilnadu, India. Appl Water Sci 3:603–612

Srinivas Y, Aghil TB, Oliver DH, Nair CN, Chandrasekar N (2015) Hydrochemical characteristics and quality assessment of groundwater along the Manavalakurichi coast, Tamil Nadu. Appl Water Sci. doi:10.1007/s13201-015-0325-8

Srinivasamoorthy K, Chidambaram S, Anandhan P, Vasudevan S (2005) Application of statistical analysis of the hydrogeochemical study of groundwater in hard rock terrain, Salem District, Tamilnadu. J Geochem 20:181–190

Steinich B, Escolero O, Marín LE (1998) Salt-water intrusion and nitrate contamination in the Valley of Hermosillo and El Sahuaral coastal aquifers, Sonora, Mexico. Hydrogeol J 6(4):518–526

Stuyfzand PJ (1989) Nonpoint sources of trace elements in potable groundwaters in the Netherlands. Proceedings 18th TWSA Water Workings. Testing and Research Institute KlWA

Stuyfzand PJ (1999) Patterns in groundwater chemistry resulting from groundwater flow. Hydrogeol J 7(1):15–27

Thilagavathi R, Chidambaram S, Prasanna MV, Singaraja C (2012) A study on groundwater geochemistry and water quality in layered aquifers system of Pondicherry region, southeast India. Appl Water Sci 2:253–269. doi:10.1007/s13201-012-0045-2

Tijani J (1994) Hydrocemical assessment of groundwater in Moro area, Kwara state, Nigeria. Environ Geol 24:194–202

Todd DK (1980) Groundwater hydrology. Wiley, New York, pp 10–138

Twarakavi NKC, Kaluarachchi JJ (2006) Sustainability of groundwater quality considering land use changes and public health risks. J Environ Manag 81:405–419

UCCC (1974) Guidelines for interpretations of water quality for irrigation. University of California Committee of Consultants, California

Uddin A, Lundberg N (1998) Cenozoic history of the Himalayan–Bengal system: sand composition in the Bengal Basin, Bangladesh. Geol Soci Am Bull 110:497–511

Vandenbohede A, Courtens C, William de Breuck L (2010) Fresh-salt water distribution in the central Belgian coastal plain: an update. Geol Belg 11(3):163–172

Vasanthavigar M, Srinivasamoorthy K, Vijayaravan K, Rajiv-Ganthi R, Chidambaram S, Anandhan P, Manivannan R, Vasudevan S (2010) Application of water quality index for groundwater quality assessment: Thirumanimuttar sub-basin, Tamil Nadu, India. Environ Monit Assess 171(1–4):595–609. doi:10.1007/s10661-009-1302-1

Vengosh A, Heumann KG, Juraski S, Kasher R (1994) Boron isotope application for tracing sources of contamination in groundwater. Environ Sci Technol 28(11):1968–1974

Wen X, Wu Y, Su J, Zhang Y, Liu F (2005) Hydrochemical characteristics and salinity of groundwater in the Ejina Basin, Northwestern China. Environ Geol 48:665–675. doi:10.1007/s00254-005-0001-7

WHO (2004) WHO guidelines for drinking water quality, Geneva. 1&2

WHO (2011) WHO guidelines for drinking-water quality, 4th edn. World Health Organization, Geneva

Wilcox LV (1948) The quality of water for irrigation, use. US Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC. Tech Bull 1962:19

Wilcox LV (1955) Classification and use of irrigation water. US Department of Agriculture, Circular No. 969, Washington D.C. USA, p 19

Woobaidullah ASM, Hasan MA, Reza MH, Noor A, Amin MK (2006) Ground water potentiality-a review of the hydrogeological data available in the coastal belt of Khulna and Satkhira districts. Dhaka Univ J Sci 42:229–233

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful to the anonymous reviewers who help for the current shape of the paper by their valuable suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Islam, S.M.DU., Bhuiyan, M.A.H., Rume, T. et al. Hydrogeochemical investigation of groundwater in shallow coastal aquifer of Khulna District, Bangladesh. Appl Water Sci 7, 4219–4236 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-017-0533-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-017-0533-5