Abstract

Zinc (Zn) is an essential micronutrient with numerous cellular functions in plants, and its deficiency represents one of the most serious problems in human nutrition worldwide. Zn deficiency causes a decrease in plant growth and yield. On the other hand, Zn could be toxic if excess amounts are accumulated. Therefore, the uptake and transport of Zn must be strictly regulated. In this review, the dominant fluxes of Zn in soil–root–shoot translocation in rice plants (Oryza sativa) are described, including Zn uptake from soils in the form of Zn2+ and Zn-DMA at the root surface, and Zn translocation to shoots. Knowledge of these fluxes could be helpful to formulate genetic and physiologic strategies to address the widespread problem of Zn-limited crop growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Zinc in biology

The variety of roles that zinc (Zn) plays in cellular processes is a good example of the diverse biological utility of metal ions. Zn is involved in protein, nucleic acid, carbohydrate, and lipid metabolism. In addition, Zn is critical to the control of gene transcription and the coordination of other biological processes regulated by proteins containing DNA-binding Zn-finger motifs (Rhodes and Klug 1993), RING fingers, and LIM domains (Vallee and Falchuk 1993). Several molecules associated with DNA and RNA synthesis are also Zn metalloenzymes, such as RNA polymerases (Wu et al. 1992), reverse transcriptases, and transcription factors (Wu and Wu 1989). Zn is a non-redox-active ion and is therefore targeted to transcription factors and other enzymes involved in DNA metabolism, as the use of redox-active metal ions for these tasks could lead to radical reactions and nucleic acid damage. However, these processes must be tightly regulated to ensure that the correct amount of Zn is present at all times. Although it is an essential nutrient, Zn could be toxic if it accumulates in excess. The precise cause of Zn toxicity is unknown, but the metal may bind to inappropriate intracellular ligands, or compete with other metal ions for enzyme active sites or transporter proteins. In order to play such diverse roles in cells, and because it cannot passively diffuse across cell membranes, Zn must be transported into the intracellular compartments of the cell where it is required for these Zn-dependent processes. A group of proteins called Zn transporters is dedicated to the transport of Zn across biological membranes.

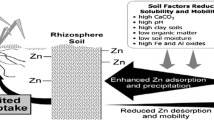

Studies of Zn uptake in biology are critical because Zn is essential for all organisms, including humans (Hambidge 2000). As Zn plays multiple roles in plant biochemical and physiological processes, even slight deficiency causes a decrease in growth, yield, and Zn content of edible plant parts. Zn deficiency is a serious agricultural problem as around one half of the cereal-growing soils in the world contain low Zn in the soil (Graham and Welch 1996; Cakmak et al. 1999). In soil, Zn is present in various forms. Among the total soil Zn content, Zn primary minerals constitute around 15%, Zn organic matter complexes around 45%, outer-sphere complexes around 20%, Zn-sorbed phosphate around 10%, and Zn-sorbed iron oxyhydroxides around 10% (Sarret et al. 2004). The solubility and availability of Zn is determined by various factors like high CaCO3, high pH, high clay soils, low organic matter, low soil moisture, and high iron and aluminum oxides (Cakmak 2008).In low Zn soils, the Zn uptake may be enhanced by the exudation of low-molecular-weight compounds like malate and mugineic acid family phytosiderophores (Arnold et al. 2010; Cakmak et al. 1994; Peng et al. 2009; Suzuki et al. 2006; Walter et al. 1994; Widodo et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 1989).

Food Zn content is very important for human health as the artificial supplementation of foods with essential minerals is often difficult to achieve, particularly in developing countries. Therefore, it has been suggested that increased levels of Zn in staple foods, e.g., rice may play a role in reducing Zn deficiency (Ruel and Bouis 1998; Graham et al. 1999; Welch and Graham 1999). Therefore, it is essential to understand the molecular mechanism through which plants mobilize, take up, translocate, and store Zn.

ZIP transporters

Higher plants take up Zn from the rhizosphere via transporters, and molecular aspects of this phenomenon are now being clarified. In the Arabidopsis thaliana genome, a large number of cation transporters potentially involved in metal ion homeostasis have been identified (Maser et al. 2001). Several members of the Zn-regulated transporters in the iron (Fe)-regulated transporter-like protein (ZIP) gene family (Guerinot 2000) have been characterized and shown to be involved in metal uptake and transport in plants (Eide et al. 1996; Korshunova et al. 1999; Vert et al. 2001, 2002; Connolly et al. 2002). The ZIP proteins are predicted to have eight transmembrane domains, with their amino- and carboxyl-terminal ends situated on the outer surface of the plasma membrane (Guerinot 2000). These proteins vary considerably in overall length due to a variable region between the transmembrane domains (TM) TM-3 and TM-4, which is predicted to be on the cytoplasmic side, providing a potential metal-binding domain rich in histidine residues. The most-conserved region of these proteins lies in a variable region that has been predicted to form an amphipathic helix, containing a fully conserved histidine that may form part of an intramembranous metal-binding site involved in transport (Guerinot 2000). The transport function is disabled when the conserved histidines or certain adjacent residues are replaced by mutation (Rogers et al. 2000).

ZIP1, ZIP3, and ZIP4 from Arabidopsis restore Zn uptake to the yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) Zn-uptake mutant, Δzrt1Δzrt2, and have been proposed to play a role in Zn transport (Grotz et al. 1998; Guerinot 2000). ZIP1 and ZIP3 are expressed in roots in response to Zn deficiency, suggesting that they transport Zn from the soil to the plant, while ZIP4 is expressed in both roots and shoots, suggesting that it transports Zn intracellularly or between plant tissues (Grotz et al. 1998; Guerinot 2000). ZIP2 and ZIP4 rescue yeast mutants deficient in copper (Cu) transport, and ZIP4 is up-regulated in Cu-deficient roots (Wintz et al. 2003). Yeast Zrt1 and Zrt2 are high- and low-affinity Zn transporters, respectively (Eide 1998; Guerinot 2000). The proposed role of ZIP transporters in Zn nutrition has been further supported by the characterization of homologs from several plant species. For example, GmZIP1 has been identified in soybean (Glycine max; Moreau et al. 2002), and functional complementation of Δzrt1Δzrt2 yeast cells showed that GmZIP1 is highly selective for Zn, but not for Fe or manganese (Mn). GmZIP1 is expressed specifically in nodules, but not in roots, stems, or leaves, and the protein is localized to the peribacteroid membrane, suggesting a role in symbiosis. In barley, Zn transporters are induced by low pH (Pedas and Husted 2009).

In rice plants (Oryza sativa), several ZIP transporter genes have been reported, e.g., OsIRT1, OsIRT2, OsZIP1, OsZIP3, OsZIP4, and OsZIP5 (Fig. 1; Ishimaru et al. 2006; Lee et al. 2010; Ramesh et al. 2003; Yang et al. 2009). OsZIP1, OsZIP3, OsZIP4, and OsZIP5 were found to be rice Zn transporters induced by Zn deficiency (Ramesh et al. 2003; Lee et al. 2010; Ishimaru et al. 2006). OsZIP1, OsZIP3, and OsZIP4 are expressed in the vascular bundles in shoots and in the vascular bundles and epidermal cells in roots (Ramesh et al. 2003; Ishimaru et al. 2006). In situ hybridization analysis revealed that OsZIP4 in Zn-deficient rice was expressed in the meristem of Zn-deficient roots and shoots, and also in vascular bundles of the roots and shoots. These results suggest that OsZIP4 is a Zn transporter that may be responsible for Zn translocation to the plant parts that require Zn.

Unrooted phylogenic tree that highlights the relationship among the ZIP transporter proteins in rice plants and A. thaliana. Unrooted phylogenic tree for the OsIRT1, OsZIPs, AtIRTs, and AtZIPs. Calculations were performed using the CLUSTAL W neighbor-joining method and the tree was visualized with TreeView.

Furthermore, we have produced transgenic rice plants over-expressing OsZIP4 under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter (Ishimaru et al. 2007). Compared to control plants, Zn concentration in 35S-OsZIP4 transgenic plants was higher in roots and lower in shoots, suggesting that OsZIP4 expression driven by the 35S promoter in the 35S-OsZIP4 root may be involved in xylem unloading and reducing the Zn transport to shoots. Northern blot analysis revealed that transcripts of OsZIP4 expression driven by the CaMV 35S promoter were detected in roots and shoots of 35S-OsZIP4 transgenic plants, but endogenous OsZIP4 transcripts were rare in roots, and abundant in shoots. Microarray analysis revealed that the genes expressed in shoots of 35S-OsZIP4 transgenic plants coincided with those induced in shoots of Zn-deficient plants. Similar results were reported for OsZIP5 overexpression plants, which accumulated more Zn in roots, whereas the shoot Zn accumulation decreased. The OsZIP5OX plants were sensitive to Zn excess, while the Oszip5 knock out plants were tolerant to Zn excess. OsZIP1 and OsZIP3 are primarily associated with Zn uptake in roots and Zn homeostasis in shoots (Ramesh et al. 2003). OsZIP4 is involved in the translocation of Zn, particularly into vascular bundles and meristem (Ishimaru et al. 2005).

Contribution of MAs to Zn uptake and translocation

The mugineic acid family phytosiderophores (MAs), play a major role in Fe acquisition from their roots to solubilize sparingly soluble Fe in the rhizosphere. Welch (1995) proposed that MAs may also contribute to the acquisition of Zn and other metal nutrients by graminaceous plants. It was reported that Zn deficiency increases the secretion of MAs from wheat (Triticum spp.) and barley (Hordeum vulgare) roots into the rhizosphere (Cakmak et al. 1994; Walter et al. 1994; Zhang et al. 1989, Suzuki et al. 2006). In rice line RIL46, Zinc-deficiency tolerance to some extent is due to the increased efflux of MAs (Widodo et al. 2010). The biosynthesis of MAs and their corresponding genes has been characterized. MAs are synthesized from methionine (Mori and Nishizawa 1987; Fig. 2). S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) synthetase converts methionine into SAM. Subsequently, three molecules of SAM are combined to form one molecule of nicotianamine (NA) by NA synthase (NAS; EC 2.5.1.43). NA is then converted to 3″-keto acid by NA aminotransferase (NAAT; EC 2.6.1.80), and 2′-deoxymugineic acid (DMA) is synthesized by DMA synthase (DMAS; Bashir et al. 2006; Bashir and Nishizawa 2006). The synthesized MAs are secreted to the rhizosphere by TOM1 (Nozoye et al. 2011). In some graminaceous species, including barley, DMA is further hydroxylated by two dioxygenases, IDS2 (EC 1.14.11.25) and IDS3 (EC 1.14.11.24; Nakanishi et al. 2000; Kobayashi et al. 2001). The genes encoding the enzymes involved in DMA synthesis have been well characterized in Fe-deficient rice and barley. The expression of HvNAS1, HvNAAT-A, HvNAAT-B, HvDMAS1, HvIDS2, and HvIDS3 is elevated in Fe-deficient barley roots (Nakanishi et al. 1993; Okumura et al. 1994; Higuchi et al. 1999; Takahashi et al. 1999; Bashir et al. 2006). In rice, the expression of OsNAS1, OsNAS2, OsNAAT1, OsDMAS1 and TOM1 increases in both roots and shoots by Fe deficiency (Inoue et al. 2003; Inoue et al. 2008; Bashir et al. 2006; Nozoye et al. 2011). The expression of OsNAS3 increases in Fe-deficient roots, but decreases in Fe-deficient shoots (Inoue et al. 2003). Promoter-β-glucuronidase (GUS) analysis suggests that OsNAS1 and OsNAS2 and TOM1 are involved in DMA secretion as these genes are expressed in all root cells (Bashir et al. 2006; Inoue et al. 2003; Nozoye et al. 2011). However, OsNAS3 may not be involved in DMA secretion because its expression is restricted to the pericycle and companion cells of the roots (Inoue et al. 2003).

Recently, we showed that the expression of NASHOR2, a NAS gene in barley (Herbik et al. 1999), and HvNAAT-B was elevated in Zn-deficient barley shoots, but that the expression of IDS2 and IDS3 was not detected in Zn-deficient shoots (Suzuki et al. 2006). However, the expression of HvNAS1, HvNAAT-A, HvNAAT-B, IDS2, and IDS3 was elevated in both Zn- and Fe-deficient roots, while the expression of these genes was not observed in Fe-deficient shoots (Suzuki et al. 2006). Therefore, we suggest that Zn deficiency induces DMA synthesis in barley shoots, while both Zn and Fe deficiency induce MAs synthesis and secretion in barley roots.

YSL transporter

A yellow stripe 1 (YS1) gene important for the uptake of Fe3+-MAs has been identified in maize (Curie et al. 2001). ZmYS1 functionally complements yeast strains that are defective in Fe uptake on media containing Fe3+-MAs, but not on media containing Fe3+ citrate, suggesting that ZmYS1 is a MAs-dependent Fe transporter (Curie et al. 2001). ZmYS1 has a broad specificity for metals and ligands, and can transport MAs-bound metals, including Zn, Cu, and nickel (Schaaf et al. 2004, Murata et al. 2006). On the other hand, Roberts et al. (2004) reported that ZmYS1 transported Fe3+- and Cu-MAs, but not Zn-MAs.

Our search for YS1 homologs in the O. sativa L. ssp. japonica (cv. Nipponbare) rice genomic database identified 18 putative OsYSLs that exhibit 36–76% sequence similarity to YS1 (Koike et al. 2004). The phloem-specific expression of OsYSL2 suggests that it is involved in the phloem transport of Fe. OsYSL2 transports Fe2+-NA and Mn2+-NA, but did not transport Fe3+-MAs. These results suggest that OsYSL2 is a rice metal-NA transporter that is responsible for phloem transport of Fe and Mn. OsYSL15 and OsYSL18 transports Fe (III)-DMA (Aoyama et al. 2009; Inoue et al. 2009).

Until now, a Zn-NA transporter or Zn-MAs transporter involved in Zn translocation has not been identified in rice plants. However, the ZmYS1-transport Zn-MAs. NA, and DMA were synthesized in Zn-deficient shoots, and rice plants have 18 putative OsYSLs. These data suggest the existence of Zn-NA or Zn-MAs transporters for Zn translocation in rice shoots.

Zn translocation of Zn2+ and Zn-DMA

Recently, we showed that Zn-deficient barley roots absorb more Zn-DMA than Zn2+ (Suzuki et al. 2006). In contrast, less Zn-DMA than Zn2+ was absorbed from the roots of Zn-deficient rice. These findings are correlated with a change in the amount of MAs secreted under Zn deficiency. In barley, MAs secretion is increased by Zn deficiency, and this contributes to the absorption of Zn from the soil. However, in rice, the level of DMA secretion was slightly reduced (Suzuki et al. 2008b); therefore, rice may prefer to absorb Zn2+ rather than Zn-DMA.

Moreover, we also showed that the amount of endogenous DMA in rice shoots increase due to Zn deficiency, corresponding to the increased expression of OsNAS3, OsNAAT1, and OsDMAS1 in Zn-deficient shoots (Suzuki et al. 2008a, b). In accordance with the dramatic increase in OsNAAT1 expression in Zn-deficient shoots, the amount of endogenous NA in shoots was remarkably reduced by Zn deficiency. In contrast to the increase in MAs secretion caused by Zn deficiency in barley, the amount of DMA secreted from rice roots slightly decrease. Furthermore, our PETIS experiment clearly show that more 62Zn is translocated to the newest leaf when 62Zn-DMA is supplied compared to the conditions when 62Zn2+ was supplied, while the opposite tendency was observed at the bottom of the leaf sheath (Suzuki et al. 2008a, b), suggesting that Zn-DMA is the preferred form for long-distance transport of Zn in Zn-deficient rice.

An appreciation for the importance of Zn in molecular biology, structural biology, and nutritional sciences has grown rapidly over the past 15 years (Berg and Shi 1996). However, many questions about the mechanisms that Zn uses in plants still remain, such as the Zn efflux system, Zn homeostasis inside the cell, and transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation. Further studies will enable us to clarify the mechanism of Zn transport and to manipulate the distribution of Zn to produce crops that can tolerate stress due to Zn deficiency, as well as enhance the Zn content of food crop seeds.

Seed Zn localization

Seed germination is triggered by an array of complex process governed by numerous factors mainly, hormone signaling pathways, light, and water. Germination also involves the movement of metal ions like Zn, so that it may be utilized efficiently. Rice seeds contain not only Zn but also NA and DMA, and the amount of DMA is significantly higher than that of NA (Usuda et al. 2009; Masuda et al. 2009). NA, DMA, and Zn is mobilized during germination in rice (Takahashi et al. 2009). In rice, Zn localizes to embryo, endosperm and to the aleurone layer of the seeds. The Zn content is particularly high in embryo (Takahashi et al. 2009). During germination, Zn in the endosperm decreases while in the embryo, high levels of Zn accumulates in the radicle and leaf primordium (Fig. 3). With time, Zn increases in the scutellum and the vascular bundle of the scutellum. In the scutellum, Zn accumulates to the endosperm similarly to Fe (Takahashi et al. 2009; Bashir et al. 2010). Zn is distributed in the leaf primordium and the root tip, 36 h after germination. Zn is observed to the area assumed to be the junction between the embryo and the dorsal vascular bundle. In a previous report we discussed (Takahashi et al. 2009) that proteins abundant in seeds decrease 1 to 2 days after sowing while biological functions such as respiration become active 3 days after sowing. Microarray analysis of germinating rice seeds suggest that ZIP family members decrease during germination (Nozoye et al. 2007). As Zn accumulation in meristematic tissues is limited in the embryo (Fig. 3). A decrease in OsZIP family transcripts might be necessary for this type of partial localization of Zn. Similarly to other members of the rice ZIP family genes, OsZIP4 expression in whole seeds decreased in the 2–3 days after sowing.

Zn localization and histochemical localization of GUS activity derived from OsZIP4 promoter. a–c The normalized X-ray fluorescence intensities scaled from blue (minimum) to red (maximum). a 12 h; b 24 h; c 36 h after sowing. d–f ZIP4 promoter-derived GUS expression. d 0 days and seeds 1–2 days (b–c) after sowing. sc scutellum, en endosperm, ep epithelium.

Rice genotypes differ greatly in Zn use efficiency and grain Zn contents and this aspect has been investigated by various researchers (Graham et al. 1999; Nagarathna et al. 2010; Neue, et al. 1998; Refuerzo et al. 2009; Wissuwa et al. 2006; Wissuwa et al. 2008; Yang et al. 1998). Rice grain Zn concentrations ranged from 15.9 to 58.4 mg kg−1 (Graham et al. 1999), suggesting ample variation for this trait that might be exploited through conventional breeding. Another study revealed that native soil Zn status is the dominant factor to determine grain Zn concentrations followed by genotype and fertilizer. Depending on soil Zn status, grain Zn concentrations could range from 8 to 47 mg kg−1 in a single genotype (Wissuwa et al., 2006; Wissuwa et al., 2008).

The localization and genetic control mechanisms of Zn in Zn-deficient rice plants is summarized in Fig. 4. Using this knowledge, different approaches have been adopted to increase the Zn in rice seed. Transgenic lines harboring HvNAS1 driven by the 35S or actin1 promoter accumulated more Fe and Zn in polished T2 seeds, showing a positive correlation between Fe and NA/DMA concentrations in seeds (Masuda et al. 2009). These results suggest that NA overproduction enhances the translocation of Fe and Zn to rice grains. Higuchi et al. (2001a, b) produced rice lines expressing HvNAS1, resulting in an increased NA content in the roots and leaves under Fe-sufficient conditions. However, the seed Fe and Zn concentrations did not increase in plants grown under Fe-deficient conditions in calcareous paddy fields or under Fe-sufficient conditions in andosol paddy fields (Masuda et al. 2008; Suzuki et al. 2008a). Recently, we demonstrated that the expression of OsYSL2, if driven by a suitable promoter, resulted in a significant increase in grain Fe (Ishimaru et al. 2010). The expression of OsYSL2 when controlled by the sucrose transporter promoter increased the Fe concentration in polished rice up to 4.4-fold compared to WT. These results suggest that controlling the temporal and spatial expression could be effective to increase the Zn in rice seeds.

Various groups have already demonstrated the potential to increase the Zn concentration of rice grains. Traditional breeding, maker-assisted breeding, and plant transformation techniques and a combination of these techniques can be further exploited to mitigate the Zn deficiency in plants and humans.

References

Aoyama T, Kobayashi T, Takahashi M, Nagasaka S, Usuda K, Kakei Y, et al. OsYSL18 is a rice iron(III)-deoxymugineic acid transporter specifically expressed in reproductive organs and phloem of lamina joints. Plant Mol Biol. 2009;70:681–92.

Arnold T, Kirk GJD, Wissuwa M, Frei M, Zhao FJ, Mason TFD, et al. Evidence for the mechanisms of zinc uptake by rice using isotope fractionation. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33:370–81.

Bashir K, Ishimaru Y, Nishizawa NK. Iron uptake and loading into rice grains. Rice. 2010;3:122–30.

Bashir K, Nishizawa NK. Deoxymugineic Acid synthase; a gene important for Fe-Acquisition and homeostasis. Plant Signal Behav. 2006;1:290–2.

Bashir K, Inoue H, Nagasaka S, Takahashi M, Nakanishi H, Mori S, et al. Cloning and characterization of deoxymugineic acid synthase genes from graminaceous plants. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32395–402.

Berg JM, Shi Y. The galvanization of biology: a growing appreciation for the roles of zinc. Science. 1996;271:1081–5.

Cakmak I. Enrichment of cereal grains with zinc: agronomic or genetic biofortification? Plant Soil. 2008;302:1–17.

Cakmak I, Kalayci M, Ekiz H, Braun HJ, Yilmaz A. Zinc deficiency as an actual problem in plant and human nutrition in Turkey: a NATO-Science for Stability Project. Field Crops Res. 1999;60:175–88.

Cakmak I, Gulut KY, Marschner H, Graham RD. Effect of zinc and iron deficiency on phytosiderophore release in wheat genotypes differing in zinc deficiency. J Plant Nutr. 1994;17:1–17.

Connolly EL, Fett JP, Guerinot ML. Expression of the IRT1 metal transporter is controlled by metals at the levels of transcript and protein accumulation. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1347–57.

Curie C, Panavience Z, Loulergue C, Dellaporta SL, Briat JF, Walker EL. Maize yellow stripe1 encodes a membrane protein directly involved in Fe(III) uptake. Nature. 2001;409:346–9.

Eide D, Broderius M, Fett J, Guerinot ML. A novel iron regulated metal transporter from plants identified by functional expression in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5624–8.

Eide D. The molecular biology of metal ion transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu Rev Nutr. 1998;18:441–69.

Graham R, Senadhira D, Beebe S, Iglesias C, Monasterio I. Breeding for micronutrient density in edible portions of staple food crops: conventional approaches. Field Crops Res. 1999;60:57–80.

Graham RD, Welch RM. Breeding for staple-food crops with high micronutrient density: working Papers on Agricultural Strategies for Micronutrients, No.3. Washington DC: International Food Policy Institute; 1996.

Grotz N, Fox T, Connolly E, Park W, Guerinot M, Eide D. Identification of a family of zinc transporter genes from Arabidopsis that respond to zinc deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7220–4.

Guerinot ML. The ZIP family of metal transporters. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1465:190–8.

Hambidge M. Human zinc deficiency. J Nutr. 2000;130:1344S–9.

Herbik A, Koch G, Mock HP, Dushkov D, Czihal A, Thielmann J, et al. Isolation, characterization and cDNA cloning of nicotianamine synthase from barley. A key enzyme for iron homeostasis in plants. Eur J Biochem. 1999;265:231–9.

Higuchi K, Suzuki K, Nakanishi H, Yamaguchi H, Nishizawa NK, Mori S. Cloning of nicotianamine synthase genes, novel genes involved in the biosynthesis of phytosiderophores. Plant Physiol. 1999;119:471–9.

Higuchi K, Takahashi M, Nakanishi H, Kawasaki S, Nishizawa NK, Mori S. Analysis of transgenic rice containing barley nicotianamine synthase gene. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2001a;47:315–22.

Higuchi K, Watanabe S, Takahashi M, Kawasaki S, Nakanishi H, Nishizawa NK, et al. Nicotianamine synthase gene expression differs in barley and rice under Fe-deficient conditions. Plant J. 2001b;25:159–67.

Inoue H, Higuchi K, Takahashi M, Nakanishi H, Mori S, Nishizawa NK. Three rice nicotianamine synthase genes, OsNAS1, OsNAS2, and OsNAS3 are expressed in cells involved in long-distance transport of iron and differentially regulated by iron. Plant J. 2003;36:366–81.

Inoue H, Kobayashi T, Nozoye T, Takahashi M, Kakei Y, Suzuki K, et al. Rice OsYSL15 is an iron-regulated iron(iii)-deoxymugineic acid transporter expressed in the roots and is essential for iron uptake in early growth of the seedlings. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:3470–9.

Inoue H, Takahashi M, Kobayashi T, Suzuki M, Nakanishi H, Mori S, et al. Identification and localisation of the rice nicotianamine aminotransferase gene OsNAAT1 expression suggests the site of phytosiderophore synthesis in rice. Plant Mol Biol. 2008;66:193–203.

Ishimaru Y, Masuda H, Bashir K, Inoue H, Tsukamoto T, Takahashi M, et al. Rice metal-nicotianamine transporter, OsYSL2, is required for long distance transport of iron and manganese. Plant J. 2010;62:379–90.

Ishimaru Y, Masuda H, Suzuki M, Bashir K, Takahashi M, Nakanishi H, et al. Overexpression of the OsZIP4 zinc transporter confers disarrangement of zinc distribution in rice plants. J Exp Bot. 2007;58:2909–15.

Ishimaru Y, Suzuki M, Kobayashi T, Takahashi M, Nakanishi H, Mori S, et al. OsZIP4, a novel zinc-regulated zinc transporter in rice. J Exp Bot. 2005;56:3207–14.

Ishimaru Y, Suzuki M, Tsukamoto T, Suzuki K, Nakazono M, Kobayashi T, et al. Rice plants take up iron as an Fe3+−phytosiderophore and as Fe2+. Plant J. 2006;45:335–46.

Kobayashi T, Nakanishi H, Takahashi M, Kawasaki S, Nishizawa NK, Mori S. In vivo evidence that Ids3 from Hordeum vulgare encodes a dioxygenase that converts 2′-deoxymugineic acid to mugineic acid in transgenic rice. Planta. 2001;212:864–71.

Koike S, Inoue H, Mizuno D, Takahashi M, Nakanishi H, Mori S, et al. OsYSL2 is a rice metal-nicotianamine transporter that is regulated by iron and expressed in the phloem. Plant J. 2004;39:415–24.

Korshunova YO, Eide D, Clark WG, Guerinot ML, Pakrasi HB. The IRT1 protein from Arabidopsis thaliana is a metal transporter with broad specificity. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;40:37–44.

Lee S, Jeong HJ, Kim SA, Lee J, Guerinot ML, An G. OsZIP5 is a plasma membrane zinc transporter in rice. Plant Mol Biol. 2010;73:507–17.

Maser P, Thomine S, Schroeder JI, Ward JM, Hirschi K, Sze H, et al. Phylogenetic relationships within cation transporter families of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:1646–67.

Masuda H, Suzuki M, Morikawa KC, Kobayashi T, Nakanishi H, Takahashi M, et al. Increase in iron and zinc concentrations in rice grains via the introduction of barley genes involved in phytosiderophore synthesis. Rice. 2008;1:100–8.

Masuda H, Usuda K, Kobayashi T, Ishimaru Y, Kakei Y, Takahashi M, et al. Overexpression of the barley nicotianamine synthase gene HvNAS1 increases iron and zinc concentrations in rice grains. Rice. 2009;2:155–66.

Moreau S, Thomson RM, Kaiser BN, Trevaskis B, Guerinot ML, Udvardi MK, et al. GmZIP1 encodes a symbiosis-specific zinc transporter in soybean. J Biol Chem. 2002;15:4738–46.

Mori S, Nishizawa NK. Methionine as a dominant precursor of phytosiderophores in Graminaceae plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 1987;28:1081–92.

Murata Y, Ma JF, Yamaji N, Ueno D, Nomoto K, Iwashita T. A specific transporter for iron(III)–phytosiderophore in barley roots. Plant J. 2006;46:563–72.

Nagarathna TK, Shankar AG, Udayakumar M. Assessment of genetic variation in zinc acquisition and transport to seed in diversified germplasm lines of rice (Oryza sativa L.). J Agric Tech. 2010;6:171–8.

Nakanishi H, Okumura N, Umehara Y, Nishizawa NK, Chino M, Mori S. Expression of a gene specific for iron deficiency (Ids3) in the roots of Hordeum vulgare. Plant Cell Physiol. 1993;34:401–10.

Nakanishi H, Yamaguchi H, Sasakuma T, Nishizawa NK, Mori S. Two dioxygenase genes, Ids3 and Ids2, from Hordeum vulgare are involved in the biosynthesis of muginetic acid family phytosiderophores. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;44:199–207.

Neue HU, Quijano C, Senadhira D, Setter T. Strategies for dealing with micronutrient disorders and salinity in lowland rice systems. Field Crops Res. 1998;56:139–55.

Nozoye T, Inoue H, Takahashi M, Ishimaru Y, Nakanishi H, Mori S, et al. The expression of iron homeostasis-related genes during rice germination. Plant Mol Biol. 2007;64:35–47.

Nozoye T, Nagasaka S, Kobayashi T, Takahashi M, Sato Y, Sato Y, et al. Phytosiderophore efflux transporters are crucial for iron acquisition in graminaceous plants. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(7):5446–54.

Okumura N, Nishizawa NK, Umehara Y, Ohata T, Nakanishi H, Yamaguchi T, et al. A dioxygenase gene (Ids2) expressed under iron deficiency conditions in the roots of Hordeum vulgare. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;25:705–19.

Pedas P, Husted S. Zinc transport mediated by barley ZIP proteins are induced by low pH. Plant Signal Behav. 2009;4:842–5.

Peng GX, FuSuo Z, Hoffland E. Malate exudation by six aerobic rice genotypes varying in zinc uptake efficiency. J Environ Qual. 2009;38:2315–21.

Ramesh SA, Shin R, Eide DJ, Schachtman DP. Defferential metal selectivity and gene expression of two zinc transporters from rice. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:126–34.

Refuerzo L, Mercado EF, Arceta M, Sajese AG, Gregorio G, Singh RK. QTL mapping for zinc deficiency tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Philipp J Crop Sci. 2009;34:86.

Rhodes D, Klug A. Zinc fingers. Sci Am. 1993;268:56–65.

Roberts LA, Pierson AJ, Panaviene Z, Walker EL. Yellow stripe1. Expanded roles for the maize iron–phytosiderophore transporter. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:112–20.

Rogers EE, Eide DJ, Guerinot ML. Altered selectivity in an Arabidopsis metal transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12356–60.

Ruel MT, Bouis HE. Plant breeding: a long-term strategy for the control of zinc deficiency in vulnerable populations. Am J Clin Nutr Suppl. 1998;68:488S–94.

Sarret G, Balesdent J, Bouziri L, Garnier JM, Marcus MA, Geoffroy N, et al. Zn speciation in the organic horizon of a contaminated soil by micro-X-ray fluorescence, micro- and powder-EXAFS spectroscopy, and isotopic dilution. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:2792–801.

Schaaf G, Ludewig U, Erenoglu BE, Mori S, Kitahara T, von Wirén N. ZmYS1 functions as a proton-coupled symporter for phytosiderophore- and nicotianamine-chelated metals. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9091–6.

Suzuki M, Takahashi M, Tsukamoto T, Watanabe S, Matsuhashi S, Yazaki J, et al. Biosynthesis and secretion of mugineic acid family phytosiderophores in zinc-deficient barley. Plant J. 2006;48:85–97.

Suzuki M, Morikawa KC, Nakanishi H, Takahashi M, Saigusa M, Mori S, et al. Transgenic rice lines that include barley genes have increased tolerance to low iron availability in a calcareous paddy soil. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2008a;54:77–85.

Suzuki M, Tsukamoto T, Inoue H, Watanabe S, Matsuhashi S, Takahashi M, et al. Deoxymugineic acid increases Zn translocation in Zn-deficient rice plants. Plant Mol Biol. 2008b;66:609–17.

Takahashi M, Nozoye T, Kitajima B, Fukuda N, Hokura N, Terada Y, et al. In vivo analysis of metal distribution and expression of metal transporters in rice seed during germination process by microarray and X-ray Fluorescence Imaging of Fe, Zn, Mn, and Cu. Plant Soil. 2009;325:39–51.

Takahashi M, Yamaguchi H, Nakanishi H, Shioiri T, Nishizawa NK, Mori S. Cloning two genes for nicotianamine aminotransferase, a criticalenzyme in iron acquisition (strategy II) in graminaceous plants. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:947–56.

Usuda K, Wada Y, Ishimaru Y, Kobayashi T, Takahashi M, Nakanishi H, et al. Genetically engineered rice containing larger amounts of nicotianamine to enhance the antihypertensive effect. Plant Biotech J. 2009;7:87–95.

Vallee BL, Falchuk KH. The biochemical basis of zinc physiology. Physiol Rev. 1993;73:79–118.

Vert G, Briatt JF, Curie C. Arabidopsis IRT2 gene encodes a root periphery iron transporter. Plant J. 2001;26:181–9.

Vert G, Grotz N, DeÂdaldeÂchamp F, Gaymard F, Guerinot ML, Briat JF, et al. IRT1, an Arabidopsis transporter essential for iron uptake from the soil and for plant growth. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1223–33.

Walter A, Romheld V, Marschner H, Mori S. Is the release of phytosiderophores in zinc-deficient wheat plants a response to impaired iron utilization? Physiol Plant. 1994;92:493–500.

Welch RM, Graham RD. A new paradigm for world agriculture: meeting human needs: productive, sustainable, nutritious. Field Crops Res. 1999;60:1–10.

Welch RM. Micronutrient nutrition of plants. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1995;14:49–82.

Widodo, Broadley MR, Rose T, Frei M, Tanaka JP, Yoshihashi T, et al. Response to zinc deficiency of two rice lines with contrasting tolerance is determined by root growth maintenance and organic acid exudation rates, and not by zinc-transporter activity. New Phytol. 2010;186:400–14.

Wintz H, Fox T, Wu YY, Feng V, Chen W, Chang HS, et al. Expression profiles of Arabidopsis thaliana in mineral deficiencies reveal novel transporters involved in metal homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2003;28:47644–53.

Wissuwa M, Ismail AM, Graham RD. Rice grain zinc concentrations as affected by genotype, native soil-zinc availability, and zinc fertilization. Plant Soil. 2008;306:37–48.

Wissuwa M, Ismail AM, Yanagihara S. Effects of zinc deficiency on rice growth and genetic factors contributing to tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:731–41.

Wu YF, Huang JW, Sinclair BR, Powers L. The structure of the zinc sites of Escherichia coli DNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:25560–7.

Wu YF, Wu WC. Zinc in DNA replication and transcription. Annu Rev Nutr. 1989;7:251–72.

Yang X, Huang J, Jiang Y, Zhang HS. Cloning and functional identification of two members of the ZIP (Zrt, Irt-like protein) gene family in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36:281–7.

Yang X, Ye ZQ, Shi CH, Zhu ML, Graham RD. Genotypic differences in concentrations of iron, manganese, copper, and zinc in polished rice grains. J Plant Nutr. 1998;21:1453–62.

Zhang F, Romheld V, Marschner H. Effect of zinc deficiency in wheat on the release of zinc and iron mobilizing root exudates. Pflanzenernahr Bodenk. 1989;152:205–10.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (Green Technology Project IP-5003). We thank Dr. Tomoko Nozoye and Dr. Motofumi Suzuki for valuable discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ishimaru, Y., Bashir, K. & Nishizawa, N.K. Zn Uptake and Translocation in Rice Plants. Rice 4, 21–27 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12284-011-9061-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12284-011-9061-3