Abstract

Here, we present the results of a comprehensive study of the distribution, evolution, heterogeneity, and phylogenetic relationships of the Ty3-Gypsy Atlantys long terminal repeat retrotransposable element family in Oryza. Atlantys element-related sequences make up a significant fraction of the genomes of species from the Officinalis complex as well as the Oryza ridleyi and O. granulata genomes. The proliferation of Atlantys elements, in many cases, took place after respective speciation events occurred. Most of the retrotranspositional events occurred within the last three million years. Atlantys is an ancient and ubiquitous component of the genus Oryza and has made significant contributions to genome size variation across the genus. Its structure is unusual when compared to other Ty3-Gypsy elements and its proliferation in the different Oryza species has been rapid and differential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

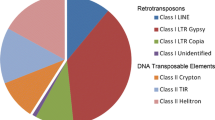

Repetitive sequences play significant roles in the evolution of genome architecture, gene expression, and speciation. The largest fraction of repetitive sequences in most plant genomes is composed of transposable elements [11] that are classified into two main major categories: class 1 RNA elements and class 2 or DNA elements, based on the kind of molecules used as intermediates in the replicative mechanism of transposition [7]. Long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons, (LTR-RTs), a particular group of class 1 elements, are ubiquitous in plants [12, 18, 45, 53]. The biology of retrotransposition, whereby identical LTRs are found at the ends of retrotransposons after transposition, makes long terminal repeat sequences ideal molecular signatures for understanding the timing of LTR-RT insertion, for understanding the mechanisms of LTR-RT elimination, and for the determining the phylogenetic relationships of LTR-RT families.

Several studies have shown that LTR-RTs are the principal components responsible for genome size expansion in the grasses, accounting for as much as 50–90% of the barley, maize, and wheat genomes [29, 35, 42, 46, 47]. The spectacular effects of retrotranspositional bursts of single LTR-RT families on the genome size variation have been recently described in Gossypium ssp., Oryza var., and Vicia pannonica [3, 17, 36, 39]. For example, both the Oryza australiensis [EE] and O. granulata [GG] diploid genomes increased by 100% and 50%, respectively, by bursts of a few LTR-RTs families in a relatively short periods of time, subsequent to speciation.

LTR-RTs can also act as potential controlling elements. Through insertion, they can inactivate or modify genes [27, 49] and can also have genome wide effects contributing to transcriptional interference by producing sense or antisense transcripts of adjacent genes [22]. Retrotransposon activity has been reported in plants for some LTR-RTs such as Tnt1 in tobacco [16], BARE-1 in barley [46, 47], Tos10, Tos17, and Tos19 elements in rice [19] and OGRE in V. pannonica [37].

The genus Oryza is composed of 24 species comprising [26, 50] 10 distinct genome types (six diploid; four tetraploid) and having a 3.6-fold genome size variation. Two species are cultivated with O. sativa being the most important food crop in the world. The relevance of rice as staple food resource, its compact genome, and role as a “model” species for the genomic studies of cereals [14] have spawned massive research efforts that have led to the production of an extensive set of structural and functional genomics information, including two draft genomic sequences of the O. sativa subspecies indica and japonica [15, 56] as well as a high quality finished sequence of the japonica genome [20]. We are using a whole genus approach to study the genus Oryza and have established an experimental research platform composed of 12 bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) fingerprint/end sequence physical maps of the 10 genome types aligned to the rice reference genome sequence (www.omap.org) [55], as well as an unbiased set of genomic sequences derived from random sheared shotgun libraries [57], to address fundamental questions in plant evolution and biology. Using this platform, we previously described the discovery and analysis of several retrotranspositional bursts that have led to large increases in the genome sizes of both the EE (O. australiensis) and GG (O. granulata) genome species [3, 39]. Here, we present the results of a comprehensive study of the Ty3-Gypsy Atlantys [21] element in the genus Oryza. We explored the distribution, evolution, heterogeneity, and phylogenetic relationships of the Atlantys element both within and between the Oryza species using three different sets of data. First, 27 BACs representative of 11 Oryza species were used to isolate complete Atlantys elements and LTRs. Secondly, more than 72,000 random sheared sequences representative of 12 Oryza species were used in abundance estimates and phylogenetic analyses. Finally, the complete genomic sequences of both the indica and japonica subspecies of O. sativa were used to complement and validate the results on a whole genome scale.

Results

Atlantys is ubiquitous in the genus Oryza

The Ty-3-Gypsy Atlantys element was first identified in O. sativa by McCarthy and co-workers [33] as part of an extensive survey to identify and classify LTR-RTs in rice. To isolate and analyze Atlantys elements and LTRs from other Oryza species, a sample of 27 sequenced BACs (totaling more than 4.2 Mbp of sequence) from 11 different Oryza species was searched using LTR sequences from two O. sativa Atlantys elements (Table 1) as query in nucleotide Basic Local Alignment Sequence Tool (BlastN) searches under relaxed settings. Complete elements from O. punctata [BB], O. granulata [GG], and O. alta [CCDD] and a nearly complete (because of a truncated 5′ LTR) element from O. officinalis [CC] were identified. The length of these elements ranged from 11,226 bp in O. granulata to the 13,728 bp in O. sativa subspecies japonica. These elements were classified as members of the Atlantys family because of their reciprocal LTR similarity and the topology of a neighbor-joining (NJ) phylogenetic tree made using conserved reverse transcriptase (RT) coding domains of the isolated elements and homologous sequences of several other O. sativa Ty3-Gypsy elements. All the RT domains of the putative Atlantys elements clustered with the O. sativa Atlantys sequence in a single clade with a support of 100% bootstrap replicates (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the structure of the complete Atlantys-like elements (Fig. 2) was conserved across the various species including an unusual third partial open reading frame (ORF) located close to the 3′ LTR on the opposite strand, with respect to the gag_pol coding region. This partial ORF encodes a putative protein with sequence similarity to an “amminotransferase-like” protein from O. sativa. However, this ORF, as with all the other Atlantys coding domains, contained several stop codons and frameshift mutations. Other canonical features of LTR retroelements such as the primer binding site (PBS) and the polypurinic tract (PPT) appeared to be highly conserved in the various Atlantys elements. Fifteen of 18 nucleotides (all except the terminal 5′-CCA-3′) of the Atlantys PBS are complementary to the 3′ end of the tRNAArg isolated in Arabidopsis thaliana [30], whereas the putative polypurinic tract showed few pyrimidines interrupting the long stretch of purines (Fig. 2).

Neighbor-joining tree generated from RT domains of the most abundant Ty3-Gypsy elements from O. sativa and Atlantys elements from Oryza genus. Reverse transcriptase sequences from complete Atlantys elements isolated and from the most important rice LTR retrotransposons were used to build a neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree. Bootstrap values were calculated for 1,000 replicates.

Detailed structural features of complete Atlantys elements. A Graphical overview. B Detailed coordinates of the Atlantys regions. LTR Long terminal repeat, gag_pol the coordinates correspond to the region homologues to the gag_pol sequence ABA95102, RT indicates the coordinates of the reverse transcriptase domains used in this study, PBS primer binding site, PPT polypurine tract, Third ORF refers to the coding domains isolated in the opposite strand of that coding for gag_pol and homologous to the sequence AAV43983.

Atlantys solo-LTRs were found in O. alta [CCDD], O. australiensis [EE], O. minuta [BBCC], and O. ridleyi [HHJJ] (one for each BAC). To isolate additional Atlantys LTRs from the wild relatives of rice, LTR sequences from the O. sativa Atlantys element were used as queries in similarity searches against a set of random sheared Oryza sequences (Table 2) generated from a previous project [57], which enabled us to reconstruct putative Atlantys LTRs for O. glaberrima [AA], O. nivara [AA], and O. rufipogon [AA]. Overall, we obtained 18 Atlantys LTRs from complete elements (10 LTRs), solo LTRs (four), truncated elements (one), and joined random sheared sequences (three). The length of the complete LTRs isolated ranged from 1,299 bp (in O. ridley) to 1,833 bp (solo-LTR in O. alta; Table 1). Their overall similarity when compared to the LTR of O. sativa Atlantys ranged from 87.1% (O. nivara Atlantys) to 50.7% (O. granulata Atlantys).

Dramatic abundance variation of Atlantys elements in the Oryza

We estimated the abundance of Atlantys elements in the Oryza in three ways. First, we determined the number of Atlantys elements (complete, truncated, and solo LTRs) in the genome sequences of both japonica and indica rice using LTRs as the query sequence in similarity searches. Only hits longer than 90% of the query length were taken into account. In the case of O. sativa ssp. indica, a total of 501 Atlantys LTRs were identified, of which 70 belonged to 35 complete elements (a complete element is constituted by the two LTRs plus the internal coding domains), 164 were part of truncated elements (because one LTR was missing and the remaining had close to its ends PBS or PPT or the integrase Ty3-Gypsy conserved domain), 182 were solo-LTR originated by intra-element recombination (all showed the canonical 5 bp long target site duplication (TSD)), and 85 LTRs were not classified because no significant signals such as PBS or PPT or TSD were found in their proximity. The latter ones could be solo-LTRs originating from inter-element unequal recombination or they could be part of highly rearranged and incomplete elements. In japonica rice, 529 complete LTRs were identified, 102 from 51 complete retroelements, 166 from truncated elements, 162 are solo-LTRs, and 99 unclassified. Considering only complete elements and solo-LTRs showing TSD, the ratio of complete elements versus solo-LTRs in indica and japonica rice was roughly 1:5 and 1:3, respectively. It should, however, be noted that the reliability of the ratio calculated in indica is questionable since the sequence used to estimate this is yet to be completed. Since the settings used in the search were extremely stringent (all the instances shorter than 90% of the query length were discarded), these figures are an underestimate of the actual amount of LTR Atlantys related sequences in O. sativa. A BlastN search collecting all the hits having significant similarity (e-value lower than 1e–10) with the Atlantys LTRs gave much higher figures—1,892 hits in O. sativa ssp. japonica and 1,945 in O. sativa ssp. indica.

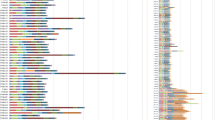

Second, to estimate the abundance of Atlantys elements in the remaining species, we used Atlantys LTRs as queries in similarity searches against sequences derived from a set of random sheared small insert shotgun libraries generated from the 12 Oryza species under investigation (Table 2). We considered both the number of significant hits (all those with an e-value lower than 1e–10 in BlastN searches) and the amount of nucleotides masked (as was obtained from RepeatMasker analysis (www.repeatmasker.org)). The results of this analysis showed that in all cases, Atlantys seemed to be significantly more abundant in the Officinalis complex (BB, CC, BBCC, CCDD, and EE genomes) [48] than in the AA genomes. In O. alta [CCDD], O. australiensis [EE], O. minuta [BBCC], and O. officinalis [CC], 4.62%, 3.31%, 3.31%, and 3.47% of the bases searched were masked, respectively. A significant amount of masked bases were also found in O. punctata [BB] (2.48%) and O. granulata [GG] (2.45%). In contrast to species of the Officinalis complex, Atlantys appeared to be depleted in the AA genomes (0.86% in O. nivara, 0.85% in O. rufipogon, and 0.79% in O. glaberrima) as well as in the [FF] genome of O. brachyantha (0.33%; Table 3).

We estimated the copy number of Atlantys LTR-related sequences in each of the 12 Oryza genomes using the results of BlastN searches and the method proposed by Hawkins et al. [17]. Surprisingly, the estimated number of Atlantys LTR-related sequences in several genomes was well above 10,000 copies: O. officinalis—16,293; O. coarctata—11,500; O. granulate—18,578; O. minuta—28,055; O. australiensis—22,583, O. alta—26,466; and O. ridleyi—20,929 (Table 3). The reliability of this approach was confirmed by analyzing 10 sets of 3,000 O. sativa in silico random sheared sequences each. The 22 significant hits obtained on average, translated into 1,426 predicted instances for O. sativa japonica which is in good agreement with the 1,892 hits obtained when the complete Oryza genome, was scanned using BlastN (Table 3).

Finally, to approximate the total genomic contribution of Atlantys related sequences to the Oryza genus, we assumed that the ratio of complete elements to solo LTRs was 1:3, as previously calculated for O. sativa var. japonica (we did not use the ratio calculated for O. sativa var. indica sequence because we consider the map-based O. sativa var. japonica sequence more reliable) and that the Atlantys element and LTR sizes were 13,000 and 1,500 bp, respectively. When these assumptions are applied to the rice RefSeq, we obtained a figure of 4.99 Mb which is about 6% lower than number of bases actually masked using RepeatMasker (5.32 Mbp). Under these assumptions, we calculated that over 8.31%, 7.90%, 7.93%, 5.93%, and 7.41% of the O. alta, O. minuta, O. officinalis, O. punctata, and O. australiensis genomes are composed of Atlantys-related sequences, respectively. Furthermore, Atlantys-related elements also appeared to make up a considerable portion of the O. ridleyi and O. granulata genomes, approximately 66.3 Mbp and 58.8 Mbp, respectively (Table 3).

Combined, these results suggest that the Atlantys transposable element family is significantly responsible for genome size increase in many of the Oryza genomes studied in this work and especially in those belonging to the Officinalis complex.

Phylogenetic relationships and variability of Atlantys in the Oryza

To investigate the phylogenetic relationship of the Atlantys elements in the Oryza, 137 paralogous Atlantys RT sequence domains, isolated from the random sheared libraries, were aligned and used to build a neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3). The results showed that paralogs from different genome types usually do not mix in the same clades. This observation also held true in many cases for paralogs from different species (with the exception of polyploids to be discussed later). These results indicate that proliferation of the Atlantys elements in the Oryza took place after events leading to the formation of different genome types and in many cases even after the occurrence of single speciation events.

Atlantys retrotransposons RT neighbor-joining tree. One hundred thirty-seven sequences similar to the Atlantys reverse transcriptase were used to build a phylogenetic tree using the neighbor-joining method. Bootstrap values were calculated for 1,000 replicates, only bootstrap values greater than 50 are reported.

The evolutionary history of Atlantys was analyzed in detail in the polyploids O. minuta [BBCC] and O. alta [CCDD] and in their diploid BB and CC genome counterparts. To obtain greater numerical power in our analysis, we investigated multiple sequence alignments between the first 5′ 300 nucleotides of LTR sequences rather than using the RT sequences. The NJ tree made using O. punctata, O. officinalis, O. minuta, and O. alta Atlantys LTRs showed a constant mixing of O. punctata and O. minuta paralogs as well as of O. officinalis and O. minuta paralogs (Fig. 4). In particular, the two O. minuta counterparts (BB and CC) separate accordingly, mixing with O. punctata and O. officinalis elements, respectively. This topology suggests that the retrotranspositional activity of the Atlantys element in these species took place before the polyploidization events leading to O. minuta. In contrast, most of the Atlantys LTR sequences of O. alta cluster in a separate clade, thereby indicating that the retrotranspositional events happened after polyploidization leading to O. alta (Fig. 4). Both scenarios were also observed when RT sequences were used for phylogenetic analysis (data not shown).

Atlantys retrotransposons in BB, CC, BBCC, and CCDD genome types. LTR neighbor-joining tree. One hundred thirteen Atlantys LTR 5′ 300 bp tracts in O. punctata (12), O. officinalis (27), O. minuta (51), and O. alta (23) were used to build a phylogenetic tree using the neighbor-joining method. Bootstrap values are based on 1,000 replicates, only those greater than 50 were reported.

Nucleotide diversity of Atlantys retrotransposons in different Oryza species was studied by analyzing the alignment of 137 Atlantys RT paralogs. We calculated nucleotide diversity using the Jukes–Cantor method (Pi-JC) and the average number of nucleotide differences (K). Pi-JC values varied from 0.09 in O. punctata [BB] to 0.28 in O. coarctata [HHKK] and the K parameter ranged from 40.6 in O. granulata [GG] to 91.9 in O. coarctata [HHKK]. With the exception of O. alta, the highest variability values were found in the polyploid species, which reflects the contribution of Atlantys elements from each of the two subgenomes. However, the interpopulation Pi value was greater than any of the single populations, again confirming that the timing of retrotransposition events primarily occurred after speciation (Table 4).

To investigate nucleotide diversity in greater depth, we measured Pi-JC values for 257 complete Atlantys LTRs (both solo-LTRs and LTRs from complete elements) identified in the O. sativa ssp. japonica reference sequence. High levels of diversity were observed in four regions—the 5′ and 3′ LTR ends, plus two internal regions as shown in Fig. 5. A similar pattern was also found for the indica subspecies reference genome sequence (data not shown). We then tried to correlate this variation with the presence of putative biological signals along the LTR sequence. A search for putative TATA boxes revealed seven positions, five of them were situated in low diversity regions, and two were located in more variable regions (Fig. 5). While it is impossible to validate the function of the putative TATA boxes in silico, it should be pointed out that the TATA box found around 400 nucleotides downstream of the 5′ LTR end is highly conserved in all the 14 complete Atlantys LTRs isolated from the other Oryza species (Fig. 5).

Nucleotide variation in Atlantys LTRs in O. sativa. A Nucleotide diversity along the O. sativa var. japonica Atlantys LTRs. Values on x-axis correspond to the nucleotide position on the LTR alignment. On the y-axis, values of the nucleotide diversity (Pi) measure calculated using a sliding window of 50 bp and a step of 5 bp. The positions of putative TATA boxes are indicated by arrows. B Detail of the Atlantys LTRs alignment corresponding to the putative TATA box indicated with “*” in A. _5 5′ LTR, _3 3′ LTR, _s solo-LTR.

Solo-LTRs, timing of Atlantys retrotransposition, and removal through unequal homologous recombination

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the ability of an organism to counteract genome size expansion caused by LTR retroelement transposition [5] such as unequal homologous recombination at LTR sites leading to the creation of solo-LTRs. Although we could not study this mechanism in the wild relatives of rice, due to relatively short read lengths of the random sheared sequences as compared with full-length Atlantys elements, we were able to determine the ratio of full-length Atlantys elements to solo-LTRs in the O. sativa ssp. japonica and indica reference sequences at 1:3 and 1:5, respectively. These ratios were significantly lower from the expected ratio of 1:1.5 [31] and provided evidence that unequal homologous recombination may have played a significant role in the attenuation of Atlantys copy number in domesticated rice. Phylogenetic analysis of a random set of 91 LTRs from complete Atlantys elements and solo-LTRs from both rice subspecies could not resolve the LTRs into distinct clades suggesting that the counteracting mechanism leading to the formation of solo-LTRs was contemporary to the retrotranspositional events (Fig. 6).

O. sativa Atlantys LTR (from complete elements and solo-LTRs) neighbor-joining tree. Ninety-one randomly picked LTRs from both complete elements and solo-LTRs in indica and japonica O. sativa varieties were used to build a phylogenetic tree using the neighbor-joining method. Bootstrap values are based on 1,000 replicates, only those greater than 50 were reported.

Furthermore, it should be noted that many of the BACs used to identify Atlantys elements from the wild relatives of rice also contained solo LTRs (e.g., O. alta, O. minuta, O. australiensis, and O. ridleyi). Although the sample is limited, the presence of solo LTRs provides additional evidence that removal of complete Atlantys elements by unequal homologous recombination was active in other Oryza species.

To determine the timing of Atlantys element insertion into the japonica and indica genomes, we used the “genome paleontology” approach proposed by SanMiguel et al. [43] whereby mutation rates are compared for pairs of LTRs derived from complete Atlantys elements (51 from O. sativa ssp. japonica and 35 from ssp. indica) using a substitution rate 2 × 10−8 substitutions per synonymous site per year [52]. Results from both species were very similar and were therefore evaluated together. The overall majority of insertion events appear to have occurred recently in evolutionary time as more than 97% of the elements inserted less than 3 million years ago (MYA) and only 2.8% inserted more than 3 MYA (Table 5). Although the sample size is small, estimates of the insertion times of Atlantys elements in the other Oryza species (Table 1) where all the insertions date back to less than 1 MYA suggest a time scale of the insertion events similar to that obtained in domesticated rice. To further support the recent retrotranspositional history of Atlantys elements in Oryza, we used blastclust (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/blast/documents/blastclust.html) to cluster the 5′ 300 bp Atlantys LTR tracts from each of the Oryza species individually. For many of the species that have a significant number of tracts isolated (at least 10), it was possible to find LTR tracts sharing more than 97% similarity over their complete length. In O. alta, five out of 23 tracts clustered; in O. granulata, seven out of 51 clustered; and in O. minuta and O. officinalis, 12 out of 51 and five out of 27 clustered, respectively. This degree of similarity could be roughly translated, using a molecular paleontology approach, into insertion times as recent as 1 MYA, thereby supporting the concept that the retrotranspositional history of the Atlantys element family in the Oryza is recent.

Discussion

The analysis of 12 random sheared genomic libraries representative of 12 Oryza species and 10 distinct genome types enabled us to gain important insights into the distribution and the evolutionary history of what appears to be one of the most significant genomic components of many Oryza genomes—the Ty3-Gypsy element Atlantys. This element was found to be ubiquitous in the Oryza which is not surprising since the ubiquity of LTR retrotransposons in the entire plant kingdom has been well established and the presence of the same family could easily cross the genus divide. For example, Atlantys-like elements have also been found in A. thaliana and Lotus corniculatus [21]. More interesting, however, is that Atlantys accumulated differentially across the Oryza. Although differential accumulation of LTR-RTs families has already been demonstrated in the Oryza, for Wallabi [39] and Gran3 [3] in O. australiensis and in O. granulata, respectively, Atlantys has attained extremely elevated copy number levels in several species but especially in the “Officinalis complex” [48] where it represents a significant fraction of these genomes: 8.31%, 7.90%, 7.93%, 5.93%, and 7.41% of the O. alta [CCDD], O. minuta [BBCC], O. officinalis [CC], O. punctata [BB], and O. australiensis [EE] genomes, respectively.

We demonstrated through phylogenetic and comparative approaches that the Atlantys element has proliferated rapidly in various Oryza genomes. In many cases, its copy number increase postdates speciation events (e.g., O. alta, O. australiensis, O. granulata, O. ridleyi, O. coarctata). Interesting insights into Atlantys proliferation dynamics were provided by the analysis of the polyploids O. minuta [BBCC] and O. alta [CCDD] and their diploid counterparts (O. punctata [BB] and O. officinalis [CC]). In O. alta, Atlantys proliferation events postdated its speciation thereby constituting an example of retrotransposition activation that could have been induced by “genomic shock” [34] during polyploidization. Some studies have indicated that O. australiensis [EE] is the closest living relative of the CCDD genome species; in particular, the E genome has been proposed as being related to the DD subgenome suggesting that an E genome ancestor may have played a role in the formation of CCDD tetraploids [4, 13, 54]. The Atlantys phylogenetic analysis does not support such a view but it is consistent with a different one which rules out the E genome as direct donor of O. alta [28]. However, it should be noted that our study focused on the phylogenetic history of the retrotransposon Atlantys and not on that of its hosts. Indeed, the lack of clustering of Atlantys copies of O. australiensis and O. alta could simply reflect the effects of the recent (postspeciation) retrotranspositional burst that occurred in the polyploid O. alta without any implication in host species phylogenetic relationships. In the polyploid, O. minuta, the complement of Atlantys retroelements seems to have been inherited from the two diploid counterparts (O. punctata and O. officinalis) or, at least, there is no evidence of any postspeciation burst. The rapidity of these events is also supported by insertion date estimates performed on complete Atlantys elements isolated from various Oryza hosts where we found that the vast majority of the events detected took place in a time frame of less than 3 million years. However, we should not discount the effects of a bias toward younger elements due to our strategy of mainly relying on similarity searches used to isolate the Atlantys-like sequences and the uncertainty that is inherent with the mutation rate we used.

The mechanisms underlying the differential accumulation of Atlantys elements throughout the genus Oryza remain to be determined but are likely to have been affected by numerous factors including the effects from different genomic environments as well as different ecological conditions. Since the Atlantys element is ancient but its retrotranspositional history is recent in the Oryza, it is possible to speculate as to whether differential accumulation of Atlantys was the result of differential rates of transposition rather than different effectiveness of element removal or the combined results of the two forces. One of the possible removal mechanisms, i.e., unequal homologous recombination [44] was shown to have been active for Atlantys in almost all the species considered here, and at least in the case of O. sativa, it was contemporary to the retrotranspositional events. In both O. sativa subspecies, a large number of truncated incomplete elements were found suggesting the parallel action of illegitimate recombination [9] along with unequal homologous recombination in removing Atlantys elements.

Even if the Atlantys-like element structure is retained throughout the Oryza, not surprisingly their LTR sequences are quite divergent. Such evidence, coupled with the high copy number of this element, makes Atlantys LTRs promising candidates for the design of species-specific (or at least genome type-specific) probes. Indeed, some of the most repeated species-specific probes already isolated in Oryza genomes are, as a matter of fact, tracts of the Atlantys LTRs. This is the case for the HindIII repetitive element pOD3 isolated in O. latifolia [CCDD] [23] that shares significant similarity with Atlantys LTRs isolated in our analysis from O. alta [CCDD] (more than 77% over 1,790 bp). Interestingly, no traces of this sequence could be found in the CC genomes of O. officinalis [CC] or O. minuta [BBCC] suggesting that the pOD3 repeat is DD subgenome specific or that it proliferated only in the CCDD polyploid genomes, as our phylogenetic analysis and nucleotide diversity estimates suggest. Another genome specific example is that of probe pBO03 [24] which is part of the Atlantys-like element LTR from O. officinalis [CC]. In this case, the authors estimated a copy number for this sequence to be around 30,000 copies assuming (wrongly) that the O. officinalis genome size was about 900 Mbp. If the correct size (651 Mbp) is used, the estimated copy number should be ∼21,700 which is in good agreement with the 16,293 figure we obtained in silico. In both cases, the authors were not able to identify these sequences as part of an LTR retroelement.

A third ORF is retained in all Atlantys elements isolated from the Oryza species. The third ORF follows the gag_pol gene but is situated on the opposite strand. This configuration eliminates the possibility that it is an envelope-like gene (in this case, it should have found in the same strand of gag_pol gene). A similar opposite strand ORF feature was found in the recently described LTR retroelement REM-1 [38]. The third ORF conservation in the Atlantys-like elements isolated in very different hosts strongly suggests that it has been selectively maintained. Although few clues are available about the function of this third ORF (it is similar to a putative AA-transferase), it is tempting to speculate about its possible role in making Atlantys one of the most important players in Oryza genomes size variation by contributing to its retrotranspositional success.

According to the model proposed by Charlesworth [8], genetic divergence of RTs should be correlated with an element’s abundance in a genome. This was not the case for the Atlantys RTs as in the case of O. alta were the copy number is elevated but the nucleotide variability is not. This discrepancy could be explained in the light of phylogenetic evidence that suggest a recent burst of Atlantys retrotransposition in this species subsequent to speciation. If the O. alta case is excluded, a clear relationship exists between nucleotide diversity values and polyploidy. Nucleotide diversity exhibited its highest values in polyploids which could be expected considering the contribution of at least two distinct subpopulations of Atlantys-like elements to these genomes. Finally, the interspecies diversity is higher than any of the intraspecies values once again pointing towards a recent time frame of retrotranspositional events.

Sequence variation was studied in depth in Atlantys element LTRs in both the indica and japonica subspecies of O. sativa. We observed a significant amount of nucleotide variation across the LTRs suggesting that there are different levels of selective pressures on these sequences, which is similar to what has been demonstrated for the LTRs of BARE-1 [51] in barley. In particular, we found a sharp decrease of nucleotide diversity in close proximity to most of the putative TATA boxes identified in silico. One sequence was highly conserved in all the Atlantys-like elements throughout the genus Oryza and is therefore considered a strong candidate for a TATA box.

Materials and methods

Random sheared libraries

Random sheared libraries were constructed as previously described [57].

O. sativa whole genome sequences

In our analyses, we used the version 3 of the IRGSP O. sativa var. japonica sequence (accession numbers AP008207 to AP008218) and the Beijing Institute of Genomics O. sativa var. indica sequence (accession numbers CM000126.1 to CM000137.1)

Putative Atlantys LTRs reconstruction

For those species in which it was not possible to identify any complete Atlantys LTRs in the BAC sequences, the corresponding random sheared sequences were searched using BlastN and the complete Atlantys LTR of the closest species as query. The significant similar tracts identified were then aligned and joined to construct the putative Atlantys LTR.

Similarity searches

Similarity searches using Atlantys LTRs as queries were carried out using the BlastN algorithm [1] run under relaxed settings (−q −2 −r 3) in order to accommodate for divergence between species. Only hits having an e value equal or lower to 1e–10 were used. The equation proposed by Hawkins et al. [17] was used to estimate the number of significantly similar hits present in the entire genome of each of the 12 Oryza species:  , where “Xobs” is the observed number of copies, N is the total number of sequence reads, n is number of targets in the genome, L is length of target sequence, m is estimated minimum length required to identify a sequence in a BLAST search (the extremely conservative value of 100 bp was used), e is number of bp sequenced from each insert and G is genome size. Cluster analysis was performed using “blastclust” (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/blast/documents/blastclust.html) with the following settings, L 0.98 S 97, meaning that all the LTR 300 bp tracts sharing at least 97% similarity over at least 98% of their length were included in the same cluster. BlastN search results were complemented and confirmed using RepeatMasker (www.repeatmasker.org) run under default settings.

, where “Xobs” is the observed number of copies, N is the total number of sequence reads, n is number of targets in the genome, L is length of target sequence, m is estimated minimum length required to identify a sequence in a BLAST search (the extremely conservative value of 100 bp was used), e is number of bp sequenced from each insert and G is genome size. Cluster analysis was performed using “blastclust” (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/blast/documents/blastclust.html) with the following settings, L 0.98 S 97, meaning that all the LTR 300 bp tracts sharing at least 97% similarity over at least 98% of their length were included in the same cluster. BlastN search results were complemented and confirmed using RepeatMasker (www.repeatmasker.org) run under default settings.

Isolation of first 5′ 300 nucleotides of LTR sequences

The first 300 bp of the 5′ Atlantys LTRs isolated in BACs were used to search the random sheared sequences. All the positive hits spanning at least 90% of the query length (270 out of 300 bp) were extracted and used in phylogenetic analyses.

Phylogenetic analysis

All alignments were carried out using the program “MUSCLE” [10] run under default settings. Neighbor-joining trees were produced and edited using the program MEGA (version 3) [25]. Nucleotide distances were calculated using the program DNAsp [41] and the program “Distmat” included in EMBOSS package [40]. All sequence editing was performed using the appropriate programs from the EMBOSS package.

Search for putative TATA boxes

Putative TATA boxes were identified using the program “OPROF” (http://www.isrec.isb-sib.ch/ssa/oprof.html) [6].

BAC sequences

The BACs used to isolate complete Atlantys elements and LTRs were produced and sequenced in the frame of different researches related to OMAP (www.omap.org). They are representative of 11 Oryza species. For each species, these are the details about the number of BACs searched, their origin and total length:

- O. rufipogon :

-

four BACs were sequenced from the individual with the accession ID #IRGC 105491 for a total of 545,208 bp

- O. glaberrima :

-

two BACs from accession ID #IRGC 96717; total bp of 268,621

- O. nivara :

-

two BACs from accession ID #IRGC 100897; total bp of 382,790

- O. punctata :

-

two BACs from accession ID #IRGC 105690; total bp of 295,593

- O. officinalis :

-

two BACs from accession ID #IRGC 100896; total bp of 273,319

- O. minuta :

-

two BACs from accession ID #IRGC 101141; total bp of 257,921

- O. alta :

-

two BACs from accession ID #IRGC 105143; total bp of 362,466

- O. australiensis :

-

three BACs from accession ID #IRGC 100882; total bp of 423,968

- O. ridley :

-

two BACs from accession ID #IRGC 100821; total bp of 352,702

- O. coarctata :

-

two BACs from accession ID #IRGC 104502; total bp of 360,876

- O. granulata :

-

four BACs from accession ID #IRGC 102118; total bp of 619,459

Accession numbers

Sequences used in this paper were submitted to the GSS division of GenBank under the following accession numbers:

-

Random Sheared libraries: EI028463–EI035999 (O. alta), EI36000–EI043358 (O. australiensis), EI043359–EI046735 (O. brachyantha), EI46736–EI56259 (O. coarctata), EI056260–EI59753 (O. glaberrima), EI059754–EI066441 (O. granulata), EI066442–EI075900 (O. minuta), EI-075901–EI079003 (O. nivara), EI079004–EI083851 (O. officinalis), EI083852–EI86995 (O. punctata), EI086996–EI098086 (O. ridleyi), EI098087–EI100641 (O. rufipogon).

-

O. alta complete “Atlantys” element: EU257654

-

O. granulata compete “Atlantys” element: EU257655

-

O. officinalis truncated “Atlantys” element: EU257656

-

O. punctata complete “Atlantys” element: EU257657

-

O. minuta solo “Atlantys” LTR: EU257658

-

O. glaberrima joined “Atlantys” LTR: EU257659

-

O. nivara joined “Atlantys” LTR: EU257660

-

O. rufipogon joined “Atlantys” LTR: EU257661

-

O. alta solo “Atlantys” LTR: EU257662

-

O. australiensis solo “Atlantys” LTR: EU257663

-

O. ridleyi solo “Atlantys” LTR: EU257664

-

O. sativa var. Japonica complete “Atlantys” element: AP008212.1 from 17105002 to 17118729

-

O. sativa var. indica complete “Atlantys” element: CM000136 from 18570076 to 18583547

References

Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–402.

Ammiraju JS, Luo M, Goicoechea JL, Wang W, Kudrna D, Mueller C, et al. The Oryza bacterial artificial chromosome library resource: construction and analysis of 12 deep-coverage large-insert BAC libraries that represent the 10 genome types of the genus Oryza. Genome Res. 2006;16:140–7.

Ammiraju JS, Zuccolo A, Yu Y, Song X, Piegu B, Chevalier F, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of an ancient retrotransposon family provides insights into evolution of genome size in the genus Oryza. Plant J. 2007;52:342–51.

Bao Y, Ge S. Origin and phylogeny of Oryza species with the CD genome based on multiple-gene sequence data. Plant Syst Evol. 2004;249:55–6.

Bennetzen JL, Ma J, Devos KM. Mechanisms of recent genome size variation in flowering plants. Ann Bot (Lond). 2005;95:127–32.

Bucher P, Trifonov EN. Compilation and analysis of eukaryotic POL II promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:10009–26.

Capy P, Langin T, Higuet D, Maurer P, Bazin C. Do the integrases of LTR-retrotransposons and class II element transposases have a common ancestor? Genetica 1997;100:63–72.

Charlesworth B. Genetic divergence between transposable elements. Genet Res. 1986;48:111–8.

Devos KM, Brown JK, Jeffrey BL. Genome size reduction through illegitimate recombination counteracts genome expansion in Arabidopsis. Genome Res. 2002;12:1075–9.

Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–7.

Feschotte C, Jiang N, Wessler SR. Plant transposable elements: where genetics meets genomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:329–41.

Flavell AJ, Dunbar E, Anderson R, Pearce SR, Hartley R, Kumar A. Ty1-copia group retrotransposons are ubiquitous and heterogeneous in higher plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3639–44.

Ge S, Sang T, Lu B-R, Hong D-Y. Phylogeny of rice genomes with emphasis on origins of allotetraploid species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14400–5.

Goff SA. Rice as a model for cereal genomics. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1999;2:86–9.

Goff SA, Ricke D, Lan T-H, Presting G, Wang R, Dunn M, et al. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica). Science 2002;296:92–100.

Grandbastien M-A, Spielmann A, Caboche M. Tnt1, a mobile retroviral-like transposable element of tobacco isolated by plant cell genetics. Nature 1989;337:376–80.

Hawkins J, Kim H, Nason JD, Wing RA, Wendel JF. Differential lineage-specific amplification of transposable elements is responsible for genome size variation in Gossypium. Genome Res. 2006;16:1252–61.

Hirochika H, Hirochika R. Ty1-copia group retrotransposons as ubiquitous components of plant genomes. Jpn J Genet. 1993;68:35–46.

Hirochika H, Sugimoto K, Otsuki Y, Tsugawa H, Kanda M. Retrotransposons of rice involved in mutations induced by tissue culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7783–8.

International Rice Genome Sequencing Project. The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature 2005;436:793–800.

Jurka J, Kapitonov VV, Pavlicek A, Klonowski P, Kohany O, Walichiewicz J. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110:462–7.

Kashkush K, Feldman M, Levy AA. Transcriptional activation of retrotransposons alters the expression of adjacent genes in wheat. Nat Genet. 2003;33:102–6.

Kiefer-Meyer M, Reddy AS, Delseny M. Characterization of a dispersed repetitive DNA sequence associated with the CCDD genome of wild rice. Genome 1995;38:681–8.

Kiefer-Meyer M, Reddy AS, Delseny M. Complex arrangement of dispersed repeated DNA sequences in Oryza officinalis. Genome 1996;39:183–90.

Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment briefings. Bioinformatics 2004;5:150–63.

Kush G. Origin, dispersal, cultivation and variation of rice. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;35:25–34.

Leprinc A-S, Grandbastien M-A, Christian M. Retrotransposons of the Tnt1B family are mobile in Nicotiana plumbaginifolia and can induce alternative splicing of the host gene upon insertion. Plant Mol Biol. 2001;47:533–41.

Li C-B, Zhang D-M, Ge S, Lu B-R, Hong D-Y. Differentiation and inter-genomic relationships among C, E and D genomes in the Oryza officinalis complex (Poaceae) as revealed by multicolor genomic in situ hybridization. Theor Appl Genet. 2001;103:197–203.

Li W, Zhang P, Fellers JP, Friebe B, Gill BS. Sequence composition, organization, and evolution of the core Triticeae genome. Plant J. 2004;40:500–11.

Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–64.

Ma J, Devos KM, Bennetzen JL. Analyses of LTR-retrotransposon structures reveal recent and rapid genomic DNA loss in rice. Genome Res. 2004;14:860–9.

Martinez CP, Arumuganathan K, Kikuchi H, Earle ED. Nuclear DNA content of ten rice species as determined by flow cytometry. Jpn J Genet. 1994;69:513–23.

McCarthy EM, Liu J, Lizhi G, McDonald JF. Long terminal repeat retrotransposons of Oryza sativa. Genome Biol. 2002;3:RESEARCH0053.

McClintock B. The significance of responses of the genome to challenge. Science 1984;226:792–801.

Meyers BC, Tingey SV, Morgante M. Abundance, distribution, and transcriptional activity of repetitive elements in the maize genome. Genome Res. 2001;11:1660–76.

Neumann P, Koblizkova A, Navratilova A, Macas J. Significant expansion of Vicia pannonica genome size mediated by amplification of a single type of giant retroelement. Genetics 2006;173:1047–56.

Neumann P, Pozarkova D, Macas J. Highly abundant pea LTR retrotransposon Ogre is constitutively transcribed and partially spliced. Plant Mol Biol. 2003;53:399–410.

Perez-Alegre M, Dubus A, Fernandez E. REM1, a new type of long terminal repeat retrotransposon in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10628–38.

Piegu B, Guyot R, Picault N, Roulin A, Saniyal A, Kim H, et al. Doubling genome size without polyploidization: dynamics of retrotransposition-driven genomic expansions in Oryza australiensis, a wild relative of rice. Genome Res. 2006;16:1262–9.

Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. EMBOSS: The European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16:276–7.

Rozas J, Sanchez-DelBarrio JC, Messeguer X, Rozas R. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics 2003;19:2496–7.

SanMiguel P, Bennetzen JL. Evidence that a recent increase in maize genome size was caused by the massive amplification of intergene retrotransposons. Ann Bot. 1998;82(supplement A):37–44.

SanMiguel P, Gaut BS, Tikhonov A, Nakajima Y, Bennetzen JL. The paleontology of intergene retrotransposons of maize. Nat Genet. 1998;20:43–5.

Shirasu K, Schulman AH, Lahaye T, Schulze-Lefert P. A contiguous 66-kb barley DNA sequence provides evidence for reversible genome expansion. Genome Res. 2000;10:908–15.

Suoniemi A, Tanskanen J, Schulman AH. Gypsy-like retrotransposons are widespread in the plant kingdom. Plant J. 1998;13:699–705.

Suoniemi A, Anamthawat-Jonsson K, Arna T, Schulman AH. Retrotransposon BARE-1 is a major, dispersed component of the barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) genome. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;30:1321–9.

Suoniemi A, Narvanto A, Schulman AH. The BARE-1 retrotransposon is transcribed in barley from an LTR promoter active in transient assays. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;31:295–306.

Tateoka T. Taxonomic studies of Oryza II. Several species complexes. Bot Mag Tokyo. 1962;1:165–73.

Varagona MJ, Purugganan M, Wessler SR. Alternative splicing induced by insertion of retrotransposons into the maize waxy gene. Plant Cell. 1992 ;4:811–20.

Vaughan DA, Morishima H, Kadowaki K-I. Diversity in the Oryza genus. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2003;6:139–46.

Vicient CM, Kalendar R, Schulman AH. Variability, recombination, and mosaic evolution of the barley BARE-1 retrotransposon. J Mol Evol. 2005;61:275–91.

Vitte C, Ishii T, Lamy F, Brar DS, Panaud O. Genomic paleontology provides evidence for two distinct origins of Asian rice(Oryza sativa, L.). Mol Genet Genomics. 2004;272:504–11.

Voytas DF, Cummings MP, Koniczny A, Ausubel FM, Rodermel SR. Copia-like retrotransposons are ubiquitous among plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:7124–8.

Wang Z-Y, Second G, Tanksley SD. Polymorphism and phylogenetic relationships among species in the genus Oryza as determined by analysis of nuclear RFLPs. Theor Appl Genet. 1992;83:565–81.

Wing RA, Ammiraju JS, Luo M, Kim H, Yu Y, Kudrna D, et al. The Oryza map alignment project: the golden path to unlocking the genetic potential of wild rice species. Plant Mol Biol. 2005;59:53–62.

Yu J, Hu S, Wang J, Wong GK, Li S, Liu B, et al. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica). Science 2002;296:79–92.

Zuccolo A, Sebastian A, Talag J, Yu Y, Kim H, Collura K, et al. Transposable element distribution, abundance and role in genome size variation in the genus Oryza. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7(1):152.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the NSF Plant Genome Program award #DBI-0321678 and the Bud Antle Endowed Chair to RAW. We also thank the AGI technical staff that supported this project, especially members of the BAC/EST Resource, Sequencing, and Bioinformatics Centers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Zuccolo, A., Ammiraju, J.S.S., Kim, H. et al. Rapid and Differential Proliferation of the Ty3-Gypsy LTR Retrotransposon Atlantys in the Genus Oryza. Rice 1, 85–99 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12284-008-9002-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12284-008-9002-y