Abstract

We experimentally investigate the effect of pre-bargaining communication on productive incentives in a multilateral bargaining game with joint production under two conditions: observable and unobservable investments. In both conditions, communication fosters fair sharing and is rarely used to pit individuals against each other. Proportional sharing arises with observable investments with or without communication, leading to high efficiency gains. Without investment observability, communication is widely used to truthfully report investments and call for equitable sharing, allowing substantial efficiency gains. Since communication occurs after production, our results highlight a novel indirect channel through which communication can enhance efficiency in social dilemmas. Our results contrast with previous findings on bargaining over an exogenous fund, where communication leads to highly unequal outcomes, competitive messages, and virtually no appeals to fairness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The agreement in place prior to renegotiation was an equal split.

An exception is Van Dolder et al. (2015) who report on a TV show where contestants negotiate how to split their joint profits accumulated through answering trivia questions as a team.

Absent a joint production process, outcomes tend to be positively correlated with bargaining power: i.e. who holds proposal rights. For example, in dictator, ultimatum, and multilateral bargaining games, the evidence shows that proposers typically enjoy a larger share of the endowment. In Settings with symmetric bargaining power, equal splits prevail. For details, see Roth (1987).

Several experiments have examined the unilateral allocation of a jointly-produced surplus, either by a team leader (Van der Heijden et al., 2009; Drouvelis et al., 2017) or a third party (Stoddard et al., 2014, 2020). These studies generally find that allocators reward high contributors, increasing efficiency relative to equal sharing.

See Eraslan and Evdokimov (2019) for a comprehensive review of the theoretical literature.

In our experiment communication only takes place during the proposal stage (via chat screens), not at the investment stage. We discuss this issue in light of existing literature in our final discussion.

This feature of our experiment is not common as all BF experiments we are aware of maintain the discount factor constant within a game. A recent meta-analysis Baranski and Morton (in press) showed that regardless of the discount factor in BF experiments with 3 players, the mean proposer share was equal across treatments. Thus, we do not believe this modelling and design choice has an impact on subject behavior in the laboratory. Our goal was to make sure that bargaining games did not go too far in order for sessions to end within reasonable time.

We follow the standard assumption in the literature that players vote in favor whenever indifferent.

We are grateful to Arkadi Predtetchinski for valuable insights in proving our result.

The proof is presented in Sect. 1 of the Online Appendix.

Importantly, Agranov and Tergiman (2019) show that when approval required unanimous voting, communication does not lead to unequal outcomes.

All agreements took place in round 4 or earlier, with only 2 agreements in round 4.

All the MW tests reported are robust to tests at the individual-decision level using cluster bootstrapping as an alternative way to account for within-session correlation.

These differences are significant. The p-values for MW tests are in parentheses: C-NO vs. NC-NO (0.004). NC-O vs. NC-NO (0.058). C-O vs. NC-NO (0.033). No other treatment difference is significant.

See Online Appendix Table 2 for regression results.

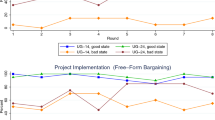

See Table 1 in the Online Appendix for session level mean investments by treatment and Fig. 1 for session level mean investments by period of play.

Pooling over observable and unobservable treatments we find no statistically significant difference between treatments with and without communication (p-value = 0.614 two-sided MW test).

In The Online Appendix, Table 3, we examine the prevalence of MWCs and 3-way splits with stronger inclusion criteria, requiring each coalition member to receive a share strictly greater than 1 or 5 tokens. Even with these stronger criteria, 3-way splits remain far more prevalent than MWCs.

The correlation coefficient between \({\hat{c}}\) and \({\hat{s}}\) is 0.02 for NC-NO, 0.13 for C-NO, 0.37 for NC-O, and 0.5 for C-O

A split is defined as proportional if the share received by each member is within 10% of the perfectly proportional share.

This happens 64% of the time in NC-NO, 59% in C-NO, 65% NC-O, and 51% C-O.

As shown in the Online Appendix, Table 4, allocations and shares often fall in between the equality and proportionality benchmarks in C-O (45.8% of allocations), but this occurs less frequently in other treatments.

In the Online Appendix 5 we examine whether subjects are consistent in the types of proposals that they make throughout the experiment. A small percentage of subjects propose consistently proportional allocations (7.2) and equal splits (11.3).

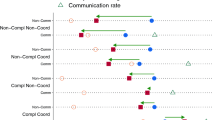

Two independent native English-speaking students were hired as coders for an hourly rate. Both received the same set of written instructions available in the Online Appendix.

On the suggestion of an anonymous referee, we also hired an additional research assistant to code further chat categories, including discussions of past or future periods of play and a friendly tone of conversation. While these categories were coded relatively infrequently, we do find a positive correlation between friendly conversation and the share allocated to a voter. The analysis for these categories is presented in the Online Appendix.

Cohen’s kappa above 0.4 indicates moderate or better agreement based on the benchmark scale of Landis and Koch (1977).

Due to an error, our research assistants were unable to code beyond round 2, which left out two cases in which subjects reached an agreement in round 3. We asked another assistant to code these conversations and re-estimated the model (Table 8 in Online Appendix). There are no meaningful changes in the estimation results.

The data show that in bargaining rounds that were not coded for proportionality, equality, or MWCs, 30% of allocations are MWCs without observability compared to only 4% with observability.

Estimation results are reported in the Online Appendix, Table 11.

See Karagözoğlu (2012) for a review, as well as the previously cited work.

References

Abbink, K., Dong, L., & Huang, L. (2018). Talking behind your back: Asymmetric communication in a three-person dilemma. CeDEx Discussion Paper Series ISSN 1749-3293.

Adams, J.S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. In Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol. 2, pp. 267–299. Elsevier.

Agranov, M., Cotton, C., & Tergiman, C. (2020). Persistence of power: Repeated multilateral bargaining with endogenous agenda setting authority. Journal of Public Economics, 184, 104126.

Agranov, M., & Tergiman, C. (2014). Communication in multilateral bargaining. Journal of Public Economics, 118, 75–85.

Agranov, M., & Tergiman, C. (2019). Communication in bargaining games with unanimity. Experimental Economics, 22(2), 350–368.

Andreoni, J., & Rao, J. M. (2011). The power of asking: How communication affects selfishness, empathy, and altruism. Journal of Public Economics, 95(7–8), 513–520.

Azerrad, M. (1992). Inside the heart and mind of Nirvana. Rolling Stone. Retrieved from Last accessed October 10, 2019.

Baranski, A. (2016). Voluntary contributions and collective redistribution. American Economic Journal, 8(4), 149–73.

Baranski, A. (2019). Endogenous claims and collective production: An experimental study on the timing of profit-sharing negotiations and production. Experimental Economics, 22(4), 857–884.

Baranski, A., & Kagel, J. H. (2015). Communication in legislative bargaining. Journal of the Economic Science Association, 1(1), 59–71.

Baranski, A., & Morton, R. (in press). The determinants of multilateral bargaining: A comprehensive analysis of Baron and Ferejohn majoritarian bargaining experiments. Experimental Economics.

Baron, D. P., Bowen, T. R., & Nunnari, S. (2017). Durable coalitions and communication: Public versus private negotiations. Journal of Public Economics, 156, 1–13.

Baron, D. P., & Ferejohn, J. A. (1989). Bargaining in legislatures. American Political Science Review, 83(4), 1181–1206.

Bochet, O., Page, T., & Putterman, L. (2006). Communication and punishment in voluntary contribution experiments. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 60(1), 11–26.

Bolton, G. E., & Brosig-Koch, J. E. (2012). How do coalitions get built? Evidence from an extensive form coalition game with and without communication. International Journal of Game Theory, 41(3), 623–649.

Bolton, G. E., Chatterjee, K., & McGinn, K. L. (2003). How communication links influence coalition bargaining: A laboratory investigation. Management Science, 49(5), 583–598.

Bradfield, A. J., & Kagel, J. H. (2015). Legislative bargaining with teams. Games and Economic Behavior, 93, 117–127.

Cappelen, A. W., Hole, A. D., Sørensen, E. Ø., & Tungodden, B. (2007). The pluralism of fairness ideals: An experimental approach. American Economic Review, 97(3), 818–827.

Cason, T. N., & Khan, F. U. (1999). A laboratory study of voluntary public goods provision with imperfect monitoring and communication. Journal of Development Economics, 58(2), 533–552.

Charness, G. (2012). Communication in bargaining experiments. In The oxford handbook of economic conflict resolution.

Charness, G., & Dufwenberg, M. (2006). Promises and partnership. Econometrica, 74(6), 1579–1601.

Charness, G., & Dufwenberg, M. (2011). Participation. American Economic Review, 101(4), 1211–37.

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46.

Cooper, R., DeJong, D. V., Forsythe, R., & Ross, T. W. (1992). Communication in coordination games. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 739–771.

Diermeier, D., & Morton, R. (2005). Experiments in majoritarian bargaining. In Social Choice and Strategic Decisions, pp. 201–226. Springer.

Dong, L., Falvey, R., & Luckraz, S. (2019). Fair share and social efficiency: A mechanism in which peers decide on the payoff division. Games and Economic Behavior, 115, 209–224.

Drouvelis, M., Nosenzo, D., & Sefton, M. (2017). Team incentives and leadership. Journal of Economic Psychology, 62, 173–185.

Duffy, J., & Feltovich, N. (2002). Do actions speak louder than words? An experimental comparison of observation and cheap talk. Games and Economic Behavior, 39(1), 1–27.

Elkins, K. (2018). The Red Sox just won the World Series-here’s how much money they’ll earn.

Eraslan, H. (2002). Uniqueness of stationary equilibrium payoffs in the Baron–Ferejohn model. Journal of Economic Theory, 103(1), 11–30.

Eraslan, H., & Evdokimov, K. S. (2019). Legislative and multilateral bargaining. Annual Review of Economics, 11(1), 443–472.

Feltovich, N., & Swierzbinski, J. (2011). The role of strategic uncertainty in games: An experimental study of cheap talk and contracts in the Nash demand game. European Economic Review, 55(4), 554–574.

Fréchette, G., Kagel, J. H., & Lehrer, S. F. (2003). Bargaining in legislatures: An experimental investigation of open versus closed amendment rules. American Political Science Review, 97(2), 221–232.

Fréchette, G., Kagel, J. H., & Morelli, M. (2005). Behavioral identification in coalitional bargaining: An experimental analysis of demand bargaining and alternating offers. Econometrica, 73(6), 1893–1937.

Fréchette, G., Kagel, J. H., & Morelli, M. (2005). Nominal bargaining power, selection protocol, and discounting in legislative bargaining. Journal of Public Economics, 89(8), 1497–1517.

Gächter, S., & Riedl, A. (2006). Dividing justly in bargaining problems with claims. Social Choice and Welfare, 27(3), 571–594.

Gangadharan, L., Nikiforakis, N., & Villeval, M. C. (2017). Normative conflict and the limits of self-governance in heterogeneous populations. European Economic Review, 100, 143–156.

Gantner, A., Horn, K., & Kerschbamer, R. (2019). The role of communication in fair division with subjective claims. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 167, 72–89.

Greiner, B. (2015). Subject pool recruitment procedures: Organizing experiments with ORSEE. Journal of the Economic Science Association, 1, 114–125.

Herings, P. J. J., Meshalkin, A., & Predtetchinski, A. (2018). Subgame perfect equilibria in majoritarian bargaining. Journal of Mathematical Economics, 76, 101–112.

Isaac, R. M., & Walker, J. M. (1988). Communication and free-riding behavior: The voluntary contribution mechanism. Economic Inquiry, 26(4), 585–608.

Karagözoğlu, E. (2012). Bargaining games with joint production. The Oxford handbook of economic conflict resolution. Oxford University Press.

Karagözoğlu, E., & Riedl, A. (2014). Performance information, production uncertainty, and subjective entitlements in bargaining. Management Science, 61(11), 2611–2626.

Kartik, N. (2009). Strategic communication with lying costs. Review of Economic Studies, 74(4), 1359–1395.

Konow, J. (2000). Fair shares: Accountability and cognitive dissonance in allocation decisions. American Economic Review, 90(4), 1072–1091.

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174.

Miller, L., Montero, M., & Vanberg, C. (2018). Legislative bargaining with heterogeneous disagreement values: Theory and experiments. Games and Economic Behavior, 107, 60–92.

Ostrom, E., Walker, J., & Gardner, R. (1992). Covenants with and without a sword: Self-governance is possible. American Political Science Review, 86(2), 404–417.

Roth, A. (1987). Bargaining phenomena and bargaining theory. Laboratory experimentation in economics: Six points of view (pp. 14–41). Cambridge University Press.

Sally, D. (1995). Conversation and cooperation in social dilemmas: A meta-analysis of experiments from 1958 to 1992. Rationality and Society, 7(1), 58–92.

Stoddard, B., Cox, C. A., & Walker, J. M. (2020). Incentivizing provision of collective goods: Allocation rules. Southern Economic Journal. Forthcoming.

Stoddard, B., Walker, J. M., & Williams, A. (2014). Allocating a voluntarily provided common-property resource: An experimental examination. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 101, 141–155.

Sutton, J. (1986). Non-cooperative bargaining theory: An introduction. The Review of Economic Studies, 53(5), 709–724.

Valley, K., Thompson, L., Gibbons, R., & Bazerman, M. H. (2002). How communication improves efficiency in bargaining games. Games and Economic Behavior, 38(1), 127–155.

Van der Heijden, E., Potters, J., & Sefton, M. (2009). Hierarchy and opportunism in teams. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 69(1), 39–50.

Van Dolder, D., Van den Assem, M. J., Camerer, C. F., & Thaler, R. H. (2015). Standing united or falling divided? High stakes bargaining in a TV game show. American Economic Review, 105(5), 402–07.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Gianluca Campanile, Thomas Yates, and Laila Al-Eisawi for excellent research assistance. We are grateful for helpful comments and conversations with Andrew Caplin, Alexander Cappelen, Guillaume Frechette, Andreas Leibbrandt, Rebecca Morton, Arkadi Predtetchinski, Ariel Rubinstein, Andy Schotter, Simon Siegenthaler, Erik Sorensen, and Bertil Tungodden. We benefited greatly from participants’ comments at the 2019 Maastricht Behavioral and Experimental Economics Symposium, 2019 New England Experimental Economics Workshop, the 2019 and 2021 ESA North American Meetings, and seminars at VCU School of Business, Norwegian School of Economics, and NYU CESS. Funding for this research was generously provided by NYU Abu Dhabi. Additional funding for research assistants was provided by VCU School of Business. Baranski gratefully recognizes financial support by Tamkeen under the NYU Abu Dhabi Research Institute Award CG005. This study is registered in the AEA RCT Registry and the unique identifying Number is: AEARCTR-0003254.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baranski, A., Cox, C.A. Communication in multilateral bargaining with joint production. Exp Econ 26, 55–77 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-022-09760-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-022-09760-z