Abstract

Thermoanaerobacter kivui is an acetogenic model organism that reduces CO2 with electrons derived from H2 or CO, or from organic substrates in the Wood–Ljugdahl pathway (WLP). For the calculation of ATP yields, it is necessary to know the electron carriers involved in coupling of the oxidative and reductive parts of metabolism. Analyses of key catabolic oxidoreductases in cell-free extract (CFE) or with purified enzymes revealed the physiological electron carriers involved. The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GA3P-DH) assayed in CFE was NAD+-specific, NADP+ was used with less than 4% and ferredoxin (Fd) was not used. The methylene-THF dehydrogenase was NADP+-specific, NAD+ or Fd were not used. A Nfn-type transhydrogenase that catalyzes reduced Fd-dependent reduction of NADP+ with NADH as electron donor was also identified in CFE. The electron carriers used by the potential electron-bifurcating hydrogenase (HydABC) could not be unambiguously determined in CFE for technical reasons. Therefore, the enzyme was produced homologously in T. kivui and purified by affinity chromatography. HydABC contained 33.9 ± 4.5 mol Fe/mol of protein and FMN; it reduced NADP+ but not NAD+. The methylene-THF reductase (MetFV) was also produced homologously in T. kivui and purified by affinity chromatography. MetFV contained 7.2 ± 0.4 mol Fe/mol of protein and FMN; the complex did neither use NADPH nor NADH as reductant but only reduced Fd. In sum, these analysis allowed us to propose a scheme for entire electron flow and bioenergetics in T. kivui.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acetogenic bacteria are a polyphyletic group and characterized by an ancient pathway for carbon dioxide fixation that is coupled to energy conservation by a chemiosmotic mechanism of ATP synthesis (Drake et al. 2008). CO2 is fixed by the Wood–Ljugdahl pathway (WLP), a pathway with two branches in which the methyl and the carbonyl group of acetyl-CoA are formed from one mol of CO2 each (Ljungdahl 1986; Wood et al. 1986). The two branches converge by forming a C–C bond, with the production of acetyl-CoA (Ragsdale and Wood 1985). In the anabolic route, acetyl-CoA is further carboxylated to pyruvate and from here, carbon flows towards the usual biosynthetic routes for the production of cell material (Fairhurst et al. 1956; Kandler 1983). In the catabolic route, acetyl-CoA is converted to acetate via acetyl-phosphate, giving rise to one mol ATP per mol of acetate (Schaupp and Ljungdahl 1974). Since one ATP is consumed in the first step of the methyl branch (Himes and Harmony 1973), the overall ATP balance by substrate level phophorylation is zero and to gain net cellular ATP, acetogens employ a chemiosmotic mechanism for ATP synthesis in addition (Schuchmann and Müller 2014). Indeed, there are two different types of respiratory enzymes present in acetogens. Both use reduced ferredoxin (Fd2−) as electron donor, but the electron acceptor is either H+ (Fd2−:H+ oxidoreductase, Ech) (Schoelmerich and Müller 2019) or NAD+ (Fd2−:NAD+ oxidoreductase, Rnf) (Biegel and Müller 2010). Electron transfer from reduced Fd to the electron acceptor leads to transport of ions (H+, Na+) across the cytoplasmic membrane and the built up of a transmembrane electrochemical ion potential which in turn drives the synthesis of ATP via a membrane-integral F1FO ATP synthase (Hess et al. 2013; Schoelmerich and Müller 2019; Kuhns et al. 2020). It is important to note that acetogens have either one of these two enzymes, never both, and are, therefore, classified as Rnf- or Ech-acetogens (Schuchmann and Müller 2014). H2 or NADH are the “waste” products of these respirations and are re-oxidized in the WLP (Müller 2003; Katsyv and Müller 2020). Autotrophic growth of acetogens on H2 + CO2 with a free energy change of only -95 kJ/mol under standard conditions is at the thermodynamic limit; taken into account environmental H2 concentrations (Thauer et al. 1977; Müller 2003; Schuchmann and Müller 2014), this value goes down to around − 20 kJ/mol, allowing for the synthesis of only ≈ 0.3 mol ATP/mol acetate (Müller 2003).

The critical number for the energetics of acetogens is the number of moles of reduced Fd available for the respiratory enzymes. This number depends on the electron carrier specificity of the enzymes of the WLP. The ultimate source of electrons is molecular hydrogen which is oxidized by electron-bifurcating hydrogenases (Schuchmann and Müller 2012; Wang et al. 2013a, b). Four moles of hydrogen are oxidized with the concomitant reduction of two moles pyridine nucleotides (NAD(P)H) and two moles reduced Fd. If more than one enzyme in the WLP requires reduced Fd as reductant, there would be a lack of electrons for the electron transport chain. Therefore, for the calculation of ATP yields, it is crucial to know the electron carrier specificity of the WLP enzymes in a given species.

The ability to utilize syngas (CO2, CO, H2) makes acetogenic bacteria to key players in the global carbon and hydrogen cycle and thus prime candidates as driving forces in a H2- and CO2-bioeconomy (Müller 2019). In the last years, tremendous progress was made in developing acetogens by metabolic engineering to convert syngas to biofuels (Daniell et al. 2012; Liew et al. 2016; Köpke and Simpson 2020) or establishing acetogens for H2 capture and storage in the biohydrogen economy (Schwarz et al. 2020, 2021; Müller 2019). However, the energetics of product formation from H2 + CO2 and CO are only poorly understood in most acetogens (Katsyv and Müller 2020).

The thermophilic acetogen Thermoanaerobacter kivui grows in mineral media with high growth rates on H2 + CO2, CO or mixtures of both (synthesis gas, syngas) (Leigh et al. 1981; Klemps et al. 1987; Hess et al. 2014; Weghoff and Müller 2016; Basen and Müller 2017). It contains the Ech complex as respiratory enzyme (Schoelmerich and Müller 2019), a H2-dependent CO2 reductase (HDCR) (Schwarz et al. 2018) as first enzyme in the carbonyl branch, a pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase (PFOR) (Katsyv et al. 2021) and a Fd2−-dependent CO dehydrogenase (Jain et al. 2021) (Table 1). Unforunately, the electron carrier specificity of the other redox enzymes of the WLP are unknown. Here, we have identified the electron carriers involved in these reactions, using cell-free extract (CFE) or purified proteins as experimental material. These studies allowed us to present the first nearly complete pathway of electron flow and the bioenergetics in this model acetogen.

Materials and methods

Growth of T. kivui

T. kivui (DSM 2030) was grown at 66 °C in complex medium under anoxic conditions in 1-l-bottles (Glasgerätebau Ochs, Bovenden-Lenglern, Germany) using 28 mM D-glucose as substrate (Weghoff and Müller 2016). The medium was prepared using the anaerobic techniques described previously (Hungate 1969; Bryant 1972). Growth was monitored by measuring the OD at 600 nm. Plating and cultivation on solid media were the same as described previously (Basen et al. 2018). 200 µg/ml kanamycin was used to select for recombinants.

Preparation of CFE

All buffers used were prepared using the anaerobic techniques described previously (Hungate 1969; Bryant 1972). All purification steps were performed under strictly anaerobic conditions at room temperature in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Grass Lake, Michigan, USA) filled with 95–98% N2 and 2–5% H2. Cells of T. kivui were harvested and washed twice in buffer A1 (50 mM Tris/HCl, 10 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgSO4, 2 mM DTE, 4 µM resazurin, 20% [v/v] glycerol, pH 7.5). The cells were resuspended in 20 ml buffer A1 including 0.5 mM PMSF and 0.1 mg/ml DNAseI and passed one time through a French pressure cell (110 MPa). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 24,000 × g, 4 °C for 20 min. The supernatant contained the CFE, which was stored at 4 °C for further investigations.

Cloning of pMU131_His-hydABC and pMU131_His-metFV

Plasmid pMU131_His-hydABC and pMU131_His-metFV were used for the expression of hydABC (TKV_c19580–TKV_c19600) and metFV (TKV_c19880–TKV_c19890) in T. kivui. The plasmids are based on plasmid pMU131 (Shaw et al. 2010), that replicates in T. kivui and confers resistance to kanamycin (Basen et al. 2018; Katsyv et al. 2021). The inserts hydABC (4219 bp) and His-metFV (1612 bp) were amplified using the primers HydABCTK_for (3) and HydABCTK_rev (4) or His-MetFVTK_for (5) and His-MetFVTK_rev (6). The backbone pMU131 (7192 bp) was amplified using the primers pMU131_for (1) and pMU131_rev (2), followed by the fusion of the PCR products via Gibson Assembly (Gibson Assembly Mastermix, NEB, Frankfurt/Main, Germany). A DNA sequence encoding a 10 × histidine-tag (His-tag) was introduced in pMU131_hydABC at the 3’-end of the gene hydA using corresponding primers His-HydA_for (9) and His-HydA_rev (10). T. kivui (DSM 2030) was transformed with the resulting plasmids pMU131_His-hydABC and pMU131_His-metFV as described previously (Basen et al. 2018). Cells were plated on agar medium containing 28 mM glucose as carbon source and 200 µg/ml kanamycin. To verify the transformation, colonies were picked and the transformed plasmids were checked using primer pairs seq1_for (7)/seq2_rev (8) binding on the pMU131 backbone and amplifying the complete His-hydABC or His-metFV locus (Fig. S1).

Production and purification of His-HydABC and His-MetFV

T. kivui pMU131_His-hydABC or pMU131_His-metFV cells were grown as described. All purification steps were performed under strictly anoxic conditions at room temperature in an anoxic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Grass Lake, Michigan, USA) filled with 95–98% N2 and 2–5% H2. Cells were harvested and washed twice in buffer A2 (50 mM Tris/HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgSO4, 10 mM imidazole, 0.5 mM DTE, 4 µM resazurin, 20% [v/v] glycerol, pH 7.5). All buffers additionally contained 10 μM FMN to avoid the loss of flavin during purification, if not otherwise specified. The cells were resuspended in 20 ml buffer A2 including 0.5 mM PMSF and 0.1 mg/ml DNAseI and passed one time through a French pressure cell (110 MPa). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 24,000 × g for 20 min. Purification of the His-tagged proteins was carried out with a nickel nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni2+-NTA) resin (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) using a gravity flow column under anoxic conditions as described previously (Katsyv et al. 2021). Fractions containing His-HydABC or His-MetFV were collected, pooled, concentrated, using 50-kDa VIVASPIN tubes, and separated on a superdex 200 10/300 GL increase prepacked column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK). The sample was loaded on a superdex 200 column equilibrated with buffer B (50 mM Tris/HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgSO4, 2 mM DTE, 4 µM resazurin, 20% [v/v] glycerol, pH 7.5) and eluted at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. HydABC or MetFV activity eluted in a single peak with a maximum at 10.2 or 11.8 ml elution volume. Fractions containing His-HydABC or His-MetFV were pooled and stored at 4 °C.

Enzyme activity assays

All enzyme assays, unless otherwise specified, were performed in 1.8 ml anoxic cuvettes (Glasgerätebau Ochs GmbH, Bovenden-Lenglern, Germany) sealed by rubber stoppers in a N2 atmosphere (1 × 105 Pa) at 66 °C at an overall liquid volume of 1 ml. One unit is defined as transfer of 2 µmol electrons/min. All measurements were performed in biological replicates. NAD(P)+/NAD(P)H was monitored spectrophotometrically at 340 nm (ε = 6.3 mM−1 cm−1), ferredoxin (Fd) (isolated from Clostridium pasteurianum (Schönheit et al. 1978)) at 430 nm (ε = 13.1 mM−1 cm−1) and methyl viologen (MV) or benzyl viologen (BV) at 600 nm (ε = 13.9 mM−1 cm−1 or ε = 12 mM−1 cm−1).

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GA3P-DH) activity was measured in buffer C (50 mM Tris/HCl, 10 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTE, pH 7.5), containing 200–500 μg CFE of glucose-grown cells, 5 mM arsenate and 4 mM NAD+/NADP+ or 30 μM Fd. The reaction was started by addition of 1 mM glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GA3P).

Methylene-THF dehydrogenase

Methylene-THF dehydrogenase activity was measured in buffer C. The assay contained 200–500 μg CFE of glucose-grown cells, 1.5 mM formaldehyde and 0.5 mM tetrahydrofolate (THF). Formaldehyde reacts spontaneously, non-enzymatically with THF to yield methylene-THF (Kallen and Jencks 1966). The reaction was started by addition of 1 mM NAD+/NADP+ or 30 µM Fd.

Transhydrogenase

Transhydrogenase activity was measured in buffer C. The assay contained 410 μg CFE of glucose-grown cells and 30 µM Fd. To keep the level of NADPH constant, 0.1 mM NADP+ were pre-reduced with 1 unit glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6P-DH) and 20 mM glucose-6-phosphate (G6P; NADP+ reducing system) as reported previously (Kremp et al. 2020). The reaction was started by addition of 1 mM NAD+.

Electron-bifurcating hydrogenase

The activity was measured in buffer D (50 mM EPPS, 10 mM NaCl, pH 8), containing 60–100 μg CFE of glucose-grown cells or 5–10 μg purified His-HydABC, 30 μM Fd and 5 µM FMN; the gas phase was 100% H2 (2 × 105 Pa). The reaction was started by addition of 4 mM NADP+/NAD+. The controls omitted either Fd or NADP+/NAD+. H2 evolution was assayed in 7.2-ml glass vials (Glasgerätebau Ochs GmbH, Bovenden-Lenglern, Germany) with 5–20 μg His-HydABC, 30 μM Fd, 5 µM FMN and 10 mM NADPH/NADH. To reduce Fd, the assay additionally contained 5 μg PFOR (isolated from T. kivui (Katsyv et al. 2021)), 400 μM coenzyme A (CoA) and 100 μM thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP). The reaction was started by addition of pyruvate at a final concentration of 10 mM. H2 was measured via gas chromatography as discribed previously (Schoelmerich and Müller 2019). The controls omitted either Fd or NADPH/NADH. To determine H2:MV oxidoreductase activity, the assay contained 0.5–20 μg purified His-HydABC or proteins from different purifications steps. The gas phase was 100% H2 (2 × 105 Pa). The reaction was started by addition of 10 mM MV. The effect of CO on the H2:MV oxidoreductase activity of His-HydABC was measured with CO concentrations (in the aqueous phase) ranged between 0–187 µM, respectively. For Km determination, the H2, NADP+ and Fd concentrations ranged between 0–325 µM, 0–4 mM and 0–200 µM, respectively. For the determination of the pH and temperature profile, the assay containing His-HydABC was preincubated for 10 min at the pH or temperature indicated. The pH optima were determined in buffer E containing 50 mM MES, 50 mM CHES, 50 mM CAPS, 50 mM Bis–Tris, 50 mM Tris, 10 mM NaCl, 4 mM DTE, 4 μM resazurin at pH 5–10, as specified in the experiments.

Methylene-THF reductase

Methylene-THF reductase (MTHFR) activity was measured in buffer F (50 mM KPi, 20 mM ascorbate, pH 7). The MV2−:methylene-THF oxidoreductase assay contained 0.5 mM THF, 1.5 mM formaldehyde and 10 mM MV. To reduce MV, 5 mM sodium dithionite was added. The reaction was started by addition of 200 μg CFE, 2–5 μg His-MetFV or 10 μg proteins from different purifications steps. To determine Fd2−:methylene-THF oxidoreductase activity the assay contained 30 μg His-MetFV, 0.5 mM THF and 1.5 mM formaldehyde. To reduce Fd, the assay additionally contained 5 μg PFOR, 400 μM CoA and 100 μM TPP. The reaction was started by addition of 10 mM pyruvate. In the controls, either Fd or methylene-THF was omitted. Methyl-THF was determined via HPLC as described recently (Dietrich et al. 2021). To determine methyl-THF:NAD+/NADP+/Fd/BV oxidoreductase the assay contained 400 μg CFE or 15–30 μg His-MetFV and 4 mM NAD+/NADP+, 30 μM Fd or 10 mM BV. The reaction was started by addition of 1 mM methyl-THF. To determine NADH/NADPH:methylene-THF oxidoreductase, the assay contained 400 μg CFE or 20 μg His-MetFV, 1.5 mM formaldehyde and 0.5 mM THF. The reaction was started by addition of 0.5 mM NADH/NADPH. To determine the Fd-dependent NADH/NADPH:methylene-THF oxidoreductase activity the assay contained 20 μg His-MetFV or 400 μg CFE, 0.5 mM THF, 0.5 mM NADH/NADPH and 30 μM Fd. The reaction was started by addition of 1.5 mM formaldehyde. To determine the NADH/NADPH:BV oxidoreductase activity, the assay contained 30 μg His-MetFV and 0.5 mM NADH/NADPH. The reaction was started by addition of 10 mM BV. For the determination of the pH and temperature profile, the assay containing His-MetFV was preincubated for 10 min at the pH or temperature indicated. The pH optima were determined in buffer E containing 50 mM MES, 50 mM CHES, 50 mM CAPS, 50 mM Bis–Tris, 50 mM Tris, 10 mM NaCl, 4 mM DTE, 4 μM resazurin at pH 5–10, as specified in the experiments.

Analytical methods

The concentration of proteins was measured according to Bradford (1976). Proteins were separated in 12% polyacrylamide gels and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue G250. The iron content of the purified enzymes was determined by colorimetric methods (Fish 1988), flavin was analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) (Bertsch et al. 2013). The molecular mass of the purified His-HydABC and His-MetFV was determined using a calibrated superdex 200 column and defined size standards (ovalbumin: 43 kDa; albumin: 158 kDa; catalase: 232 kDa; ferritin: 440 kDa).

Results and discussion

Electron carrier specificity of catabolic oxidoreductases examined in CFE of glucose-grown cells

To analyze the electron carrier specificity of the glycolytic enzyme GA3P-DH, oxidation of GA3P by CFE of glucose-grown cells was analyzed. The CFE of T. kivui catalyzed GA3P oxidation coupled to NAD+ reduction with an activity of 0.85 ± 0.15 U/mg (Fig. S2A). In contrast, NADP+ was reduced with very low rates (< 0.03 U/mg) (Fig. S2B) and Fd did not serve as electron acceptor (Fig. S2C), demonstrating that NAD+ is the cofactor used by the GA3P-DH.

The CFE also catalyzed the reduction of NADP+ with methylene-THF as electron donor (24.4 ± 1.2 U/mg) (Fig. S3A). NAD+ (Fig. S3B) or Fd (Fig. S3C) were not reduced, demonstrating a NADPH-dependent methylene-THF dehydrogenase. The MTHFR of T. kivui is of the MetFV-type (metF, TKV_c19880 and metV, TKV_c19890) (Hess et al. 2014; Öppinger et al. 2021). Methylene-THF was not reduced with NADPH or NADH as reductant in CFE. The reverse reaction, oxidation of methyl-THF was not coupled to NAD+, NADP+ or Fd reduction, but only to BV reduction (2.4 ± 0.7 U/mg). Electron bifurcation (Fd-dependent NADH/NADPH:methylene-THF oxidoreductase) was also not observed.

The genome of T. kivui codes for an electron-bifurcating, Fd-dependent transhydrogenase, NfnAB (TKV_c22270–TKV_c22280) to transfer electrons between NAD+ and NADP+ (Hess et al. 2014). CFE of T. kivui catalyzed the reduction of NAD+ with NADPH only in the presence of Fd. The NAD+-dependent NADPH:Fd oxidoreductase activity was 0.04 ± 0.01 U/mg (Fig. S4A). When Fd (Fig. S4B) or NADPH (Fig. S4C) was omitted, no NAD+ reduction was observed, indicating a functional NfnAB complex. All oxidoreductase activities measured in CFEs of glucose-grown T. kivui cells are summarized in Table 2.

Identification of a NADP+-dependent H2:Fd oxidoreductase activity in T. kivui and purification of the electron-bifurcating hydrogenase

The genome of T. kivui encodes an electron-bifurcating hydrogenase HydABC (hydC, hydB, hydA; TKV_c19580–c19600 cluster) (Hess et al. 2014), which is very similar to the NAD+-dependent H2:Fd hydrogenase HydABC of Acetobacterium woodii (HydC: 44%, HydB: 58%, HydA: 48%; Awo_c27010–c26970 cluster) (Schuchmann and Müller 2012) and Moorella thermoacetica (HydC: 49%, HydB: 57%, HydA: 56%; MOTHA_18110–18090 cluster) (Wang et al. 2013a, b) or to the NADP+-dependent H2:Fd hydrogenase of Clostridium autoethanogenum (HydC: 47%, HydB: 59%, HydA: 54%; CAETHG_3571–3569 cluster) (Wang et al. 2013a, b) and Clostridium ljungdahlii (HydC: 45%, HydB: 55%, HydA: 53%; CLJU_c14720–14,700 cluster) (Nagarajan et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2013a, b). When testing for NAD+-dependent H2:Fd oxidoreductase activity in CFE of T. kivui, Fd and NAD+ reduction with H2 as reductant was only weak (0.02 ± 0.01 U/mg). Suprisingly, NADP+ reduction with H2 as electron donor in the presence of Fd was stronger (0.05 ± 0.02 U/mg). However, Fd reduction was also measurable with H2 as electron donor alone, indicating interference with other enzymes in the CFE. To determine the cofactor specificity of the isolated HydABC hydrogenase of T. kivui, we took advantage of a plasmid-based production system in T. kivui (Katsyv et al. 2021) to produce and purify the enzyme. Therefore, we cloned hydABC together with a DNA sequence coding for a 10 × His-tag into pMU131 (Fig. S5A-D). Naturally competent cells of T. kivui were transformed with the plasmid (Fig. S1A, B), grown on glucose and CFE was prepared. The complex was purified via a genetically engineered His-tag at HydA to apparent homogeneity by Ni2+-NTA-sepharose followed by size exclusion chromatography on Superdex 200. Using this procedure, the enzyme was purified 424-fold to apparent homogeneity with an average specific H2:MV oxidoreductase activity of 7596.0 ± 2370.3 U/mg and a yield of 3.2 mg (per 2 g wet cells) (Table 3). Analyses of the purified His-HydABC separated on a 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel revealed three proteins with apparent molecular masses of ≈ 65, 70 and ≈ 18 kDa (Fig. 1A). These molecular masses correspond well with the expected sizes for HydA (TKV_c19600, 64 kDa), HydB (TKV_c19590, 68 kDa) and HydC (TKV_c19580, 18 kDa) of T. kivui. Analytical size exclusion chromatography revealed a molecular mass of 348 kDa for the purified complex, which is consistent with HydABC being a dimer. We measured 33.9 ± 4.5 mol of iron/mol of protein, which matches the prediction that HydABC contains seven [4Fe–4S] cluster, three [2Fe–2S] and one [FeFe] cluster. All current characterized bifurcating enzymes possess either a quinone or flavin group with special redox properties (Müller et al. 2018). From bioinformatic analyses, HydABC should contain one flavin, but the nature of the flavin remained to be established. After precipitation of the purified complex and subsequent separation of the flavin-containing supernatant by thin-layer chromatography (TLC), no FAD, but FMN was detected (Fig. S6A).

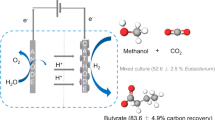

SDS-PAGE monitoring the purification process of His-HydABC and His-MetFV. Samples of the different purification steps of His-HydABC (A) and His-MetFV (B) were separated by SDS-PAGE (12%) and proteins were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G250. 10 µg of protein was applied to each lane. M, prestained page ruler; lane 1 and 7, CFE; lane 2 and 8, flow through; lane 3 and 9, wash fraction; lane 4 and 10, pooled Ni2+-NTA elution fractions; lane 5 and 11, pooled size exclusion fractions

The purified complex catalyzed electron bifurcation from H2 to Fd and NADP+ with an activity of 20.8 ± 2.5 U/mg (Fig. 2A). When NADP+ was replaced with NAD+ no activity was measurable (< 0.005 U/mg), which is contrary to previous assumptions (Basen and Müller 2017; Jain et al. 2020; Hess et al. 2014; Moon et al. 2020; Weghoff and Müller 2016). Furthermore, H2:Fd oxidoreductase activity was not detectable in the absence of NADP+, demonstrating that reduction of one electron acceptor (NADP+) was strictly dependent on the presence of the other electron acceptor (Fd). When both electron acceptors were present, they were reduced simultaneously with a 1:1 stoichiometry (slope: 0.9, Fig. 2C). FMN stimulated the HydABC activity, as described also for the purified HydABC complex of A. woodii (Schuchmann and Müller 2012). Purified His-HydABC exhibited a NADP+-dependent H2:Fd oxidoreductase activity of 15.6 ± 1.5 U/mg when FMN was omitted from the enzyme assay as opposed to 20.8 ± 2.5 U/mg with 5 µM FMN in the assay. It is important to note here, that FMN was also ommitted from buffer B during the last purification step to ensure no external FMN in the assay. The purified complex also catalyzed the reverse reaction, reduction of H+ with NADPH and reduced Fd as electron donors with an average specific activity of 9.3 ± 2.0 U/mg (Fig. 2B). All activities of His-HydABC are summarized in Table 4. Because T. kivui is able to convert CO as sole carbon and energy source, we analyzed whether the bifurcating hydrogenase is inhibited by CO. Therefore, we tested H2:MV oxidoreductase activity in the presence of different CO concentrations (Fig. 2D). Indeed, the enzyme was inhibited by CO and 50% inhibition was observed with 5.7 ± 1.2 µM CO (soluble in water), indicating a strong inhibition by low CO concentrations in vitro.

Electron-bifurcating activity of the purified His-HydABC complex. Simultaneous hydrogen-dependent reduction of Fd and NADP+ (A) was measured in 1.8-ml anoxic cuvettes containing an overall liquid volume of 1 ml under a 100% H2 atmosphere (2 × 105 Pa) at 66 °C. The assay contained 10 μg His-HydABC, 5 µM FMN and 30 μM Fd served as electron acceptor in buffer D (50 mM EPPS, 10 mM NaCl, pH 8). The reaction was started by addition of 4 mM NADP+. Reduction of NADP+ (continuous line, monitored at 340 nm) and reduction of Fd (dashed line, monitored at 430 nm) were monitored simultaneously. Hydrogen evolution from NADPH and Fd2− (B) was measured via gas chromatography. The assay contained buffer D, 20 μg His-HydABC, 30 μM Fd, 5 µM FMN and 10 mM NADPH (■). To reduce Fd (isolated from C. pasteurianum) the assay additionally contained 5 μg PFOR (isolated from T. kivui), 400 μM CoA and 100 μM TPP. The reaction was started with 10 mM pyruvate. After 18 min additional 10 mM NADPH was added as indicated. In the controls either Fd (◆) or NADPH (▼) was omitted or NADPH was replaced by NADH (▲). Stoichiometry of Fd and NADP+ reduction was calculated from the absorbance difference in (A). To calculate the ratio the amount of reduced NADP+ is plotted against the amount of reduced Fd (C). CO inhibition experiments were performed with different CO concentrations in the assay (D). The assay contained 5–10 μg His-HydABC, H2 in the atmosphere (1 × 105 Pa) and 10 mM MV in buffer D. The specific H2:MV oxidoreductase activity was ploted against the CO concentration

We assessed key biochemical properties of the purified His-HydABC including the temperature and pH profile as well as substrate affinities. To ensure an ideal reflection of the physiological conditions, we exclusively used the NADP+-dependent H2:Fd oxidoreductase assay. His-HydABC was active at temperatures ranging from 22 to 85 °C with a maximal activity of 26.8 ± 2.9 U/mg at the optimal growth temperature of T. kivui (66 °C) (Fig. S7A). At mesophilic conditions, His-HydABC activity was decreased by 86% at 22 °C and by 58% at 40 °C. At 85 °C, the activity decreased by 50%. The pH range was relatively narrow with only 22% and 55% activity at pH 6 and 10 and an optimal activity of 19.3 ± 2.4 U/mg at pH 8 (Fig. S7B). At pH 6, the activity was decreased by 78% and completely abolished at pH 5.

Next, we assessed the Km values for all reaction partners of His-HydABC. The dependence of the NADP+-dependent H2:Fd oxidoreductase reaction on H2, Fd, NADP+ and FMN was hyperbolic with saturation at 160 µM H2 (soluble in water), 30 µM Fd, 0.2 mM NADP+ and 2 µM FMN, respectively (Fig. S8). The Km values of His-HydABC for H2, Fd, NADP+ and FMN were 27.5 ± 4.5 µM, 13.6 ± 3.3 µM, 48.8 ± 10.6 µM and 0.3 ± 0.8 µM, respectively (Fig. S8). Unsurprisingly, the absence of H2, Fd or NADP+ led to a complete loss of activity.

Purification of the MTHFR

One of the biggest current uncertainties in the bioenergetics of acetogenic microorganisms is the energetics of the MTHFR reaction. The redox potential of the methylene-/methyl-THF couple of − 200 mV (Wohlfarth et al. 1990) does not allow a direct reduction of NAD+ or NADP+. One solution to this problem is electron bifurcation: Cooxidation of reduced Fd by a possible electron-bifurcating MTHFR could solve the problem. This potential complex would then transfer electrons from NADH/NADPH to methylene-THF and an additional, unidentified electron acceptor in the reductive path (Mock et al. 2014). Whether or not the MTHFR uses electron bifurcation and if so, what the second electron acceptor might be, still has to be elucidated. The picture is complicated by the fact that four different types of MTHFR´s with different subunit compositions are found in acetogens. Some definitely do not bifurcate, others maybe (Öppinger et al. 2021). Therefore, we decided to purify and charcterize the MTHFR of T. kivui.

In most acetogens, the core subunits of MTHFR are MetF and MetV (Clark and Ljungdahl 1984; Mock et al. 2014; Bertsch et al. 2015; Jeong et al. 2015; Visser et al. 2016; Öppinger et al. 2021). First inspection of genomic data of T. kivui had indicated the presence of metF (TKV_c19880) and metV (TKV_c19890) (Hess et al. 2014). No hdr and mvhD genes, as described for M. thermoacetica (Mock et al. 2014) or Sporomusa ovata (Visser et al. 2016) or a rnfC2-like gene, which was discribed for the NADH-dependent MTHFR of A. woodii (Bertsch et al. 2015), are present in the genome of T. kivui (Hess et al. 2014). To purify MetFV, metFV was cloned together with a DNA sequence coding for a 10 × His-tag into pMU131 (Fig. S5E-H) and transformed into T. kivui (Fig. S1C, D). The His-tagged MetFV was purified from the CFE of glucose-grown cells to apparent homogeneity by Ni2+-NTA-sepharose followed by size exclusion chromatography on Superdex 200. Using this procedure, the enzyme was purified 282-fold to apparent homogeneity with an average specific MV2−:methylene-THF oxidoreductase activity of 593.6 ± 161.5 U/mg and a yield of 0.4 mg (per 2 g wet cells) (Table 5). Analyses of the purified His-MetFV separated on a 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel revealed two proteins with apparent molecular masses of ≈ 33 and ≈ 28 kDa (Fig. 1B). These molecular masses correspond well with the expected sizes for MetV (23.5 kDa) and MetF (31.5 kDa) of T. kivui. Analytical size exclusion chromatography revealed a molecular mass of 174 kDa for the purified complex, which is consistent with three MetFV heterodimers. We measured 7.2 ± 0.4 mol of iron/mol of protein, which matches the prediction that MetFV contains two [4Fe–4S] cluster. From bioinformatic analyses, MetFV should contain one flavin, but the nature of the flavin remained to be established. After precipitation of the purified complex and subsequent separation of the flavin-containing supernatant by thin-layer chromatography (TLC), FMN could be detected (Fig. S6B).

Next, we assessed key biochemical properties of the purified His-MetFV including the temperature and pH profile. Therefore, we used the MV2−:methylene-THF oxidoreductase assay. His-MetFV was active at temperatures ranging from 22 to 85 °C with a maximal activity of 481.2 ± 34.9 U/mg at the optimal growth temperature of T. kivui (66 °C) (Fig. S9A). At mesophilic conditions, His-MetFV activity was decreased by 88% at 22 °C and by 56% at 40 °C. At 75 and 85 °C, the activity decreased only by 9%. The pH range was relatively narrow with 89% and 67% activity at pH 6 and 8 and an optimal activity of 258.7 ± 43.4 U/mg at pH 7 (Fig. S9B). In contrast, the activity at pH 5 and 9 was almost abolished.

The purified MetFV complex catalyzed the reduction of methylene-THF with reduced MV at a specific activity of 593.6 ± 161.5 U/mg (Fig. 3A). The complex did not catalyze the oxidation of NADH or NADPH in the presence of methylene-THF (Fig. S10A, B). NADH/NADPH:BV oxidoreductase activity was weak with only 0.2 ± 0.04 U/mg (Fig. S11). We also tested whether Fd (isolated from C. pasteurianum) was reduced by NADH or NADPH in the presence of methylene-THF, which was not the case (Fig. S12A, B). Besides reduced MV, we could identify reduced Fd as possible electron donor for the reduction of methylene-THF to methyl-THF in vitro. In the Fd2−:methylene-THF oxidoreductase assay, Fd was kept in a reduced state by the PFOR, isolated from T. kivui (Katsyv et al. 2021). From the production of methyl-THF over time, a specific activity of 0.4 ± 0.04 U/mg was calculated (Fig. 3B). The reverse reaction, oxidation of methyl-THF was not coupled to NAD+, NADP+ or Fd reduction (Fig. S13–C), but only to BV reduction (115.0 ± 42.2 U/mg) (Fig. 3C). Therefore, like in any other purified MetFV-type MTHFRs, the physiological electron carrier involved in methylene-THF reduction remains enigmatic. All activities of His-MetFV observed in this work are summarized in Table 4.

Oxidoreductase activity of the purified His-MetFV. MV2−:methylene-THF (A), Fd2−:methylene-THF (B) and methyl-THF:BV oxidoreductase activity (C) was measured in 1.8-ml anoxic cuvettes containing an overall liquid volume of 1 ml under a 100% N2 atmosphere (1 × 105 Pa) at 66 °C. MV2−:methylene-THF oxidoreductase assay contained 0.5 mM THF, 1.5 mM formaldehyde, 10 mM MV and 5 mM sodium dithionite in buffer F (50 mM KPi, 20 mM ascorbate, pH 7). The reaction was started by addition of 5 μg His-MetFV. Fd2−:methylene-THF oxidoreductase activity assay contained 30 μg His-MetFV, 30 μM Fd, 0.5 mM THF and 1.5 mM formaldehyde in buffer F (C). To reduce Fd (isolated from C. pasteurianum) the assay additionly contained 5 μg PFOR (isolated from T. kivui), 400 μM CoA and 100 μM TPP. The reaction was started by addition of 10 mM pyruvate (■). In the controls either Fd (▲) or methylene-THF (▼) was omitted. After 0.5, 1, 3, 7, 10 and 15 min the amount of produced methyl-THF was meassured via HPLC, respectively (Dietrich et al. 2021). The methyl-THF:BV oxidoreductase activity assay contained 30 μg purified His-MetFV and 1 mM methyl-THF in buffer F. The reaction was started by addition of 10 mM BV. Oxidation of MV or reduction of BV was measured at 600 nm, respectively

Recently, the MetFV-type MTHFR of C. ljungdahlii (Öppinger et al. 2021) and Eubacterium callanderi (Dietrich et al. 2021), was shown to exhibit a Fd2−:methylene-THF oxidoreductase activity in vitro as well. Fd-dependent methylene-THF reduction by MetFV would lead to a negative ATP yield during acetogenesis from H2 + CO2, therefore, reduced Fd cannot be the physiological electron donor for C. ljungdahlii and Eubacterium callanderi. This is also true for the bioenergetics of T. kivui. Therefore, it was hypothesized that methylene-THF reduction is directly coupled to a respiratory complex (Öppinger et al. 2021). In case of T. kivui, a membrane-coupled Ech-MetFV complex was assumed (Öppinger et al. 2021). Please note that T. kivui has two gene clusters encoding Ech complexes with slightly different subunit compositions (Hess et al. 2014). The exact thermodynamics for the Ech complex of T. kivui remained to be established, nevertheless it is plausible to assume a H+/2 e− stoichiometry for the Fd2−:H+ oxidoreductase of 1 to calculate ATP yields during growth. However, the free energy change is drastically increased, if methylene-THF serves as final electron acceptor (ΔG0′ = − 48.3 kJ/mol, compared to ΔG0′ = − 6.9 kJ/mol, based on a redox potential of − 414 mV for 2H+/H2). Therefore, we will indicate “1 + x” per methylene-THF reduced in the Ech-MetFV complex catalyzed reaction. For the ATP synthase, a H+/ATP stoichiometry of 3.6 is assumed (based on a number of 11 c subunits in the c-ring of the ATP synthase of Clostridium paradoxum (Ferguson et al. 2006; Meier et al. 2006). Then, acetogenesis from H2 + CO2 is coupled to the synthesis of x/3.6 mol ATP/mol acetate (Fig. 4A), whereas acetogenesis from CO yields 1.1 + (x/3.6) mol ATP/mol acetate (Fig. 4B). This model is also applicable to acetogenesis from other substrates, like glucose (Fig. 5A) or mannitol (Fig. 5B) for T. kivui. With glucose, the ATP yield is 0.87 + (x/10.8) ATP/mol acetate. For mannitol, the value is lower with 0.22 + (x/46.8) ATP/mol acetate.

Adapted from Öppinger et al. (2021). Assumed stoichiometries: H+/ATP = 3.6 (ATP synthase), 1 H+/2 e− (Ech) and 1 + x H+/2 e− (Ech-MetVF). ATP gain might be enhanced by x/3.6 ATP. CODH/ACS, CO dehydrogenase/acetyl coenzyme A synthase; THF, tetrahydrofolic acid; Ech, Energy-converting Hydrogenase

Bioenergetics of acetate formation from H2 + CO2 or CO in T. kivui. Acetate is formed from H2 + CO2 (A) or CO (B). The reducing equivalents in the WLP are provided by an H2-oxidizing, electron-bifurcating hydrogenase which reduces Fd and NADP+. We assume methylene-THF reduction by a membrane-coupled Ech-MetFV complex, which pumps 1 + x H+/2 e− across the membrane (Öppinger et al. 2021). Please note that T. kivui has two gene clusters encoding Ech complexes with slightly different subunit compositions. Ech-MetFV complex (A) and Ech complex (B) builds up a H+ gradient across the cytoplasmatic membrane. This gradient drives ATP synthesis via the H+-dependent ATP synthase. In total, x/3.6 ATP or 1.1 + (x/3.6) ATP can be synthesized per acetate produced from H2 + CO2 or CO.

Bioenergetics of acetate formation from glucose or mannitol in T. kivui. Glucose (A) or mannitol (B) are converted via glycolysis to acetate. Produced and supplied CO2 and reducing equivalents are further utilized via the WLP, giving rise for an additional acetate. Fd2− is oxidized by the bifurcating hydrogenase and the Nfn complex to produce H2 and to reduce NADP+, respectively. Hydrogen is further oxidized to reduce CO2 by the HDCR. Fd is reduced with H2 as electron donor by the Ech complex, fueled by the H+ gradient formed by the H+-dependent ATPase. We assume methylene-THF reduction by a membrane-coupled Ech-MetFV complex, which pumps 1 + x H+/2 e− across the membrane (Öppinger et al. 2021). Please note that T. kivui has two gene clusters encoding Ech complexes with slightly different subunit compositions. In total, 0.87 + (x/10.8) ATP or 0.22 + (x/46.8) ATP can be synthesized per acetate produced from glucose or mannitol. Assumed stoichiometries: H+/ATP = 3.6 (ATP synthase), 1 H+/2 e− (Ech) and 1 + x H+/2 e− (Ech-MetVF). ATP gain might be enhanced by x/3.6 ATP. CODH/ACS, CO dehydrogenase/acetyl coenzyme A synthase; THF, tetrahydrofolic acid; Nfn, transhydrogenase; Ech, Energy-converting Hydrogenase; HDCR, hydrogen-dependent CO2 reductase

Conclusion

With the data presented in this report, we have now a much better understanding of the biochemistry and metabolism of different carbon and energy sources in T. kivui. We have identified for all but one oxidoreductases the electron carriers. The MetFV-type MTHFR only uses reduced Fd as electron donor, but not NADH or NADPH. Reduced Fd can not be the direct physiological electron donor, but it is hypothesized that the MTHFR is hooked up to the Ech complex. The actual amount of ions translocated is unknown but must be bigger than 1. With H2 + CO2 as substrate x/3.6 mol ATP/mol acetate are formed, whereas acetogenesis from CO yield 1.1 + (x/3.6) mol ATP/mol acetate. During sugar fermentation, hydrogen is produced by the electron-bifurcating hydrogenase. The NADPH is provided by the Nfn complex. With glucose the ATP yield is 0.87 + (x/10.8) ATP/mol acetate and with mannitol 0.22 + (x/46.8) ATP/mol acetate.

Abbreviations

- THF:

-

Tetrahydrofolate (5,6,7,8-tetrahydropteroyl-l-glutamic acid)

- BV:

-

Benzyl viologen

- MV:

-

Methyl viologen

- CFE:

-

Cell-free extract

- GA3P:

-

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

- GA3P-DH:

-

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- G6P:

-

Glucose-6-phosphate

- G6P-DH:

-

Glucose-6-phosphate deyhdrogenase

- Fd:

-

Ferredoxin

- PFOR:

-

Pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase

- TPP:

-

Thiamine pyrophosphate

- CoA:

-

Coenzyme A

- WLP:

-

Wood–Ljungdahl pathway

- CODH/ACS:

-

Carbon monoxide dehydrogenase/acetyl-CoA synthase

- CooS:

-

Monofunctional CO dehydrogenase

- ATP:

-

Adenosine triphosphate

- Ech:

-

Energy-converting hydrogenase

- Rnf:

-

Rhodobacter nitrogen fixation

- HydABC:

-

Electron-bifurcating hydrogenase

- MTHFR:

-

Methylene-THF reductase

- [4Fe-4S]:

-

Iron-sulfur cluster

- [FeFe]:

-

Fe–Fe H-cluster

- SDS:

-

Sodium dodecyl sulfate

- OD:

-

Optical density

- HDCR:

-

Hydrogen-dependent CO2 reductase

- SEM:

-

Standard error of the mean

- FMN:

-

Flavin mononucleotide

- FAD:

-

Flavin adenine dinucleotide

- TLC:

-

Thin-layer chromatography

References

Basen M, Müller V (2017) “Hot” acetogenesis. Extremophiles 21:15–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00792-016-0873-3

Basen M, Geiger I, Henke L, Müller V (2018) A genetic system for the thermophilic acetogenic bacterium Thermoanaerobacter kivui. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e02210-02217. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02210-17

Bertsch J, Parthasarathy A, Buckel W, Müller V (2013) An electronbifurcating caffeyl-CoA reductase. J Biol Chem 288:11304–11311. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.444919

Bertsch J, Öppinger C, Hess V, Langer JD, Müller V (2015) Heterotrimeric NADH-oxidizing methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase from the acetogenic bacterium Acetobacterium woodii. J Bacteriol 197:1681–1689. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00048-15

Biegel E, Müller V (2010) Bacterial Na+-translocating ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:18138–18142. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1010318107

Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of proteine-dye-binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3

Bryant MP (1972) Commentary on the Hungate technique for culture of anaerobic bacteria. Am J Clin Nutr 25:1324–1328. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/25.12.1324

Clark JE, Ljungdahl LG (1984) Purification and properties of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, an iron-sulfur flavoprotein from Clostridium formicoaceticum. J Biol Chem 259:10845–10849. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(18)90590-9

Daniell J, Köpke M, Simpson SD (2012) Commercial biomass syngas fermentation. Energies 5:5372–5417. https://doi.org/10.3390/en5125372

Dietrich HM, Kremp F, Öppinger C, Ribaric L, Müller V (2021) Biochemistry of methanol-dependent acetogenesis in Eubacterium callanderi KIST612. Environ Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.15643 (in press)

Drake HL, Gößner AS, Daniel SL (2008) Old acetogens, new light. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1125:100–128. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1419.016

Fairhurst AS, King HK, Sewell CE (1956) Studies in amino acid biogenesis: the synthesis of alanine from pyruvate and ammonia. J Gen Microbiol 15:106–120. https://doi.org/10.1099/00221287-15-1-106

Ferguson SA, Keis S, Cook GM (2006) Biochemical and molecular characterization of a Na+-translocating F1FO-ATPase from the thermoalkaliphilic bacterium Clostridium paradoxum. J Bacteriol 188:5045–5054. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00128-06

Fish WW (1988) Rapid colorimetric micromethod for the quantitation of complexed iron in biological samples. Methods Enzymol 158:357–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/0076-6879(88)58067-9

Hess V, Schuchmann K, Müller V (2013) The ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase (Rnf) from the acetogen Acetobacterium woodii requires Na+ and is reversibly coupled to the membrane potential. J Biol Chem 288:31496–31502. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.510255

Hess V, Poehlein A, Weghoff MC, Daniel R, Müller V (2014) A genome-guided analysis of energy conservation in the thermophilic, cytochrome-free acetogenic bacterium Thermoanaerobacter kivui. BMC Genom 15:1139. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-15-1139

Himes RH, Harmony JA (1973) Formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase. CRC Crit Rev Biochem 1:501–535. https://doi.org/10.3109/10409237309105441

Hungate RE (1969) A roll tube method for cultivation of strict anaerobes. In: Norris JR, Ribbons DW (eds) Methods in microbiology. Academic Press, New York and London, pp 117–132

Jain S, Dietrich HM, Müller V, Basen M (2020) Formate is required for growth of the thermophilic acetogenic bacterium Thermoanaerobacter kivui lacking hydrogen-dependent carbon dioxide reductase (HDCR). Front Microbiol 11:59. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00059

Jain S, Katsyv A, Basen M, Müller V (2021) The monofunctional CO dehydrogenase CooS is essential for growth of Thermoanaerobacter kivui on carbon monoxide. Extremophiles (in press)

Jeong J, Bertsch J, Hess V, Choi S, Choi IG, Chang IS, Müller V (2015) Energy conservation model based on genomic and experimental analyses of a carbon monoxide-utilizing, butyrate-forming acetogen, Eubacterium limosum KIST612. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:4782–4790. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00675-15

Kallen RG, Jencks WP (1966) The mechanism of the condensation of formaldehyde with tetrahydrofolic acid. J Biol Chem 241:5851–5863. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(18)96350-7

Kandler O (1983) Carbohydrate metabolism in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 49:209–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00399499

Katsyv A, Müller V (2020) Overcoming energetic barriers in acetogenic C1 conversion. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 8:621166. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2020.621166

Katsyv A, Schoelmerich MC, Basen M, Müller V (2021) The pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase of the thermophilic acetogen, Thermoanaerobacter kivui. FEBS Open Bio 11:1332–1342. https://doi.org/10.1002/2211-5463.13136

Klemps R, Schoberth SM, Sahm H (1987) Production of acetic acid by Acetogenium kivui. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 27:229–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00252923

Köpke M, Simpson SD (2020) Pollution to products: recycling of “above ground” carbon by gas fermentation. Curr Opin Biotechnol 65:180–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2020.02.017

Kremp F, Roth J, Müller V (2020) The Sporomusa type Nfn is a novel type of electron-bifurcating transhydrogenase that links the redox pools in acetogenic bacteria. Sci Rep 10:14872. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71038-2

Kuhns M, Trifunović D, Huber H, Müller V (2020) The Rnf complex is a Na+ coupled respiratory enzyme in a fermenting bacterium Thermotoga Maritima. Commun Biol 3:431. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01158-y

Leigh JA, Mayer F, Wolfe RS (1981) Acetogenium kivui, a new thermophilic hydrogen-oxidizing, acetogenic bacterium. Arch Microbiol 129:275–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00414697

Liew F, Martin ME, Tappel RC, Heijstra BD, Mihalcea C, Köpke M (2016) Gas fermentation - a flexible platform for commercial scale production of low-carbon-fuels and chemicals from waste and renewable feedstocks. Front Microbiol 11:694–722. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00694

Ljungdahl LG (1986) The autotrophic pathway of acetate synthesis in acetogenic bacteria. Ann Rev Microbiol 40:415–450. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.mi.40.100186.002215

Meier T, Ferguson SA, Cook GM, Dimroth P, Vonck J (2006) Structural investigations of the membrane-embedded rotor ring of the F-ATPase from Clostridium paradoxum. J Bacteriol 188:7759–7764. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00934-06

Mock J, Wang S, Huang H, Kahnt J, Thauer RK (2014) Evidence for a hexaheteromeric methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase in Moorella thermoacetica. J Bacteriol 196:3303–3314. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.01839-14

Moon J, Jain S, Müller V, Basen M (2020) Homoacetogenic conversion of mannitol by the thermophilic acetogenic bacterium Thermoanaerobacter kivui requires external CO2. Front Microbiol 11:571736. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.571736

Müller V (2003) Energy conservation in acetogenic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:6345–6353. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.69.11.6345-6353.2003

Müller V (2019) New horizons in acetogenic conversion of one-carbon substrates and biological hydrogen storage. Trends Biotechnol 37:1344–1354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2019.05.008

Müller V, Chowdhury NP, Basen M (2018) Electron bifurcation: a long-hidden energy-coupling mechanism. Annu Rev Microbiol 72:331–353. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-micro-090816-093440

Nagarajan H, Sahin M, Nogales J, Latif H, Lovley DR, Ebrahim A, Zengler K (2013) Characterizing acetogenic metabolism using a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction of Clostridium ljungdahlii. Microb Cell Fact 12:118–131. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2859-12-118

Öppinger C, Kremp F, Müller V (2021) Is reduced ferredoxin the physiological electron donor for MetVF-type methylenetetrahydrofolate reductases in acetogenesis? A hypothesis. Int Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10123-021-00190-0 (in press)

Ragsdale SW, Wood HG (1985) Acetate biosynthesis by acetogenic bacteria. Evidence that carbon monoxide dehydrogenase is the condensing enzyme that catalyzes the final steps in the synthesis. J Biol Chem 260:3970–3977. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(18)89217-1

Schaupp A, Ljungdahl LG (1974) Purification and properties of acetate kinase from Clostridium thermoaceticum. Arch Microbiol 100:121–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00446312

Schoelmerich MC, Müller V (2019) Energy conservation by a hydrogenase-dependent chemiosmotic mechanism in an ancient metabolic pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116:6329–6334. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1818580116

Schönheit P, Wäscher C, Thauer RK (1978) A rapid procedure for the purification of ferredoxin from Clostridia using polyethylenimine. FEBS Lett 89:219–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-5793(78)80221-X

Schuchmann K, Müller V (2012) A bacterial electron bifurcating hydrogenase. J Biol Chem 287:31165–31171. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.395038

Schuchmann K, Müller V (2014) Autotrophy at the thermodynamic limit of life: a model for energy conservation in acetogenic bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:809–821. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro3365

Schwarz FM, Müller V (2020) Whole-cell biocatalysis for hydrogen storage and syngas conversion to formate using a thermophilic acetogen. Biotechnol Biofuels 13:32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-020-1670-x

Schwarz FM, Schuchmann K, Müller V (2018) Hydrogenation of CO2 at ambient pressure catalyzed by a highly active thermostable biocatalyst. Biotechnol Biofuels 11:237. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-018-1236-3

Schwarz FM, Oswald F, Müller V (2021) Acetogenic conversion of H2 and CO2 into formic acid and vice versa in a fed-batch operated stirred tank bioreactor. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 9:6810–6820. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c01062

Shaw AJ, Hogsett DA, Lynd LR (2010) Natural competence in Thermoanaerobacter and Thermoanaerobacterium species. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:4713–4719. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00402-10

Thauer RK, Jungermann K, Decker K (1977) Energy conservation in chemotrophic anaerobic bacteria. Bact Rev 41:100–180. https://doi.org/10.1128/br.41.1.100-180.1977

Visser M, Pieterse MM, Pinkse MW, Nijsse B, Verhaert PD, de Vos WM, Schaap PJ, Stams AJM (2016) Unravelling the one-carbon metabolism of the acetogen Sporomusa strain An4 by genome and proteome analysis. Environ Microbiol 18:2843–2855. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.12973

Wang S, Huang H, Kahnt J, Thauer RK (2013a) A reversible electron-bifurcating ferredoxin- and NAD+-dependent [FeFe]-hydrogenase (HydABC) in Moorella thermoacetica. J Bacteriol 195:1267–1275. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.02158-12

Wang S, Huang H, Kahnt J, Müller AP, Köpke M, Thauer RK (2013b) NADP+-specific electron-bifurcating [FeFe]-hydrogenase in a functional complex with formate dehydrogenase in Clostridium autoethanogenum grown on CO. J Bacteriol 195:4373–4386. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00678-13

Weghoff MC, Müller V (2016) CO metabolism in the thermophilic acetogen Thermoanaerobacter kivui. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:2312–2319. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00122-16

Wohlfarth G, Geerligs G, Diekert G (1990) Purification and properties of a NADH-dependent 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase from Peptostreptococcus productus. Eur J Biochem 192:411–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19242.x

Wood HG, Ragsdale SW, Pezacka E (1986) The acetyl-CoA pathway of autotrophic growth. FEMS Microbiol Rev 39:345–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.1986.tb01865.x

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF; ThermoSynCon) for financial support. S.J. holds a fellowship from the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VM, AK and MB designed the experiments. AK performed the experiments. SJ measured the methylene-THF dehydrogenase activity. VM and AK wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Communicated by H. Atomi.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Katsyv, A., Jain, S., Basen, M. et al. Electron carriers involved in autotrophic and heterotrophic acetogenesis in the thermophilic bacterium Thermoanaerobacter kivui. Extremophiles 25, 513–526 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00792-021-01247-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00792-021-01247-8