Abstract

A transcriptomics and proteomics approach was employed to study the expression changes associated with p-hydroxybenzoate production by the engineered Pseudomonas putida strain S12palB1. To establish p-hydroxybenzoate production, phenylalanine-tyrosine ammonia lyase (pal/tal) was introduced to connect the tyrosine biosynthetic and p-coumarate degradation pathways. In agreement with the efficient p-hydroxybenzoate production, the tyrosine biosynthetic and p-coumarate catabolic pathways were upregulated. Also many transporters were differentially expressed, one of which—a previously uncharacterized multidrug efflux transporter with locus tags PP1271-PP1273—was found to be associated with p-hydroxybenzoate export. In addition to tyrosine biosynthesis, also tyrosine degradative pathways were upregulated. Eliminating the most prominent of these resulted in a 22% p-hydroxybenzoate yield improvement. Remarkably, the upregulation of genes contributing to p-hydroxybenzoate formation was much higher in glucose than in glycerol-cultured cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The aromatic compound p-hydroxybenzoate is a building block of liquid crystal polymers, high performance plastics that are employed in electronic devices such as mobile phones. At present, such compounds are derived from fossil resources, but the increasing demand for ‘green’ polymers and resins requires other approaches to the synthesis of the building blocks that constitute these materials. Biological production from renewable feedstock is a very attractive option, although the hydrophobic nature of aromatic compounds makes specific demands on the production host. Therefore, we have developed a solvent-tolerant bacterium, Pseudomonas putida S12, as a host for the biological production of aromatic compounds from renewable resources (Verhoef et al. 2007; Nijkamp et al. 2005, 2007; Verhoef et al. 2009; Wierckx et al. 2005). This organism can tolerate a second phase of aromatic and aliphatic hydrophobic compounds such as toluene and 1-octanol, which property makes this organism an excellent platform host for the production of toxic hydrophobic compounds.

For the production of the tyrosine-derived aromatics phenol, p-hydroxystyrene and p-hydroxybenzoate, we have exploited P. putida S12_427 as a platform strain (Fig. 1; Verhoef et al. 2007, 2009; Wierckx et al. 2008). Strain S12_427 was obtained by subjecting wild-type P. putida S12 to a series of random and targeted optimization steps, key elements in which were the overexpression of the aroF-1 encoded class-I DAHP synthase, random mutagenesis and antimetabolite screening (Fig. 1; Wierckx et al. 2005). Transcriptomics and metabolic flux analyses on P. putida S12TPL3, a phenol producing strain based on P. putida S12_427, indicated that the metabolic flux towards tyrosine was significantly improved (Wierckx et al. 2008, 2009).

Genealogy of aromatics producing mutants of P. putida S12. The right hand column shows how each successive mutant was obtained. oprB-1 porin B, aroF-1 class-I DAHP synthase, pobA p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase, hpd 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase, PP1271-PP1273 multidrug efflux MFS transporter, pal/tal phenylalanine/tyrosine ammonia lyase, tpl tyrosine-phenol lyase, NTG N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine, MFP r resistant to 100 mg/l m-fluoro-DL-phenylalanine, MFT r resistant to 100 mg/l m-fluoro-L-tyrosine

For the production of p-hydroxybenzoate, tyrosine biosynthesis in P. putida S12_427 was connected to the endogenous p-coumarate catabolic pathway by introducing the pal/tal gene from Rhodosporidium toruloides (Fig. 1; Verhoef et al. 2007). This gene encodes phenylalanine/tyrosine ammonia lyase (Pal/Tal) that converts tyrosine into p-coumarate. The resulting synthetic pathway could be employed to accumulate the p-coumarate catabolic intermediate p-hydroxybenzoate, after eliminating the pobA gene encoding p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase. Figure 3 presents an overview of p-hydroxybenzoate biosynthesis in the resulting p-hydroxybenzoate producing strain, P. putida S12palB1 (Verhoef et al. 2007).

In the present study, we employed a transcriptomics and proteomics approach to study the expression changes associated with p-hydroxybenzoate production by P. putida S12palB1. Thus, insight could be provided into the effects brought about by p-hydroxybenzoate accumulation, in conjunction with the impact from the mostly non-targeted-strain improvement strategy used to obtain the parent strain, P. putida S12_427. Based on these insights, new strategies for further targeted-strain improvement may be designed. Special attention was focused on the pathways directly involved in p-hydroxybenzoate production, i.e., aromatic amino acid metabolism and p-coumarate degradation. Although previous research suggested no major differences between p-hydroxybenzoate production on glucose or glycerol (Verhoef et al. 2007), substrate specific effects at the transcript and proteome level cannot be excluded. Especially in view of the artificial connection that was made between an anabolic and a catabolic pathway to achieve p-hydroxybenzoate production, carbon source dependent regulatory effects were anticipated. The optimized p-hydroxybenzoate production strain P. putida S12palB1 was therefore compared to non-optimized control strains on glucose as well as on glycerol.

Material and methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids and culture conditions

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The media used were Luria broth (LB; Sambrook et al. 1982) and a phosphate buffered minimal medium adapted from a previously described medium (Verhoef et al. 2007) containing 3.88 g l−1 K2HPO4 and 1.63 g l−1 NaH2PO4. In minimal media, 40 mM of glycerol (MMGly) or 20 mM of glucose (MMG) were used as the sole carbon source unless stated otherwise. Antibiotics were added as required to the media at the following concentrations: gentamicin, 10 µg ml−1 (MMG and MMGly) or 25 µg ml−1 (LB); tetracycline, 10 µg ml−1 (Escherichia coli) or 60 µg ml−1 (P. putida S12). The expression of the introduced copy of aroF-1 as well as the expression of the multidrug efflux major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporter in the pBNTmfs vector was induced by addition of 0.1 mM of sodium salicylate. Shake flask experiments were performed in 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 50 ml of MMG or MMGly in a horizontal shaking incubator at 30°C. Cultures were inoculated to a starting optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.2 with cells from a preculture on MMG or MMGly.

Carbon-limited chemostat cultivations were performed as described previously (Verhoef et al. 2007) using minimal medium containing either 10 mM glucose or 20 mM glycerol, 10 mg l−1 gentamicin and 0.1 mM sodium salicylate, in 1-l fermentors with a BioFlo110 controller (New Brunswick Scientific, Nijmegen, The Netherlands). Chemostats were inoculated with a 35-ml inoculum of a late-log phase preculture on MMGly or MMG. The dilution rate (D) was set at 0.05 h−1 for 16 h, after which it was increased to 0.1 h−1. The cultures were considered to be at steady state when no significant changes were measured in cell density, stirring speed and, when applicable, p-hydroxybenzoate concentration after at least five volume changes at D = 0.1 h−1.

Sampling for microarray and 2D-DIGE analysis

Samples were drawn for microarray and two dimensional difference-in-gel-electrophoresis (2D-DIGE) analysis from chemostat cultures at steady state conditions. OD600 was measured and aromatics and carbon source concentrations were analyzed in the sample supernatants. For each condition (Table 3), three separate chemostat cultivations were performed. For microarray analysis, samples were quenched in ice-cold methanol and centrifuged. The pellet was covered by 1 ml RNAlater (Ambion, Foster City, CA, USA) and incubated for at least 1 h at 4°C, after which the RNAlater was removed. The pellet was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at−80°C. Samples for proteomics analysis were centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 20 min at 2°C. The pellet was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at−80°C.

Messenger RNA isolation and cDNA preparation for microarray analysis

Messenger RNA was isolated from the frozen pellets as described by Wierckx et al. (Wierckx et al. 2008). Random priming, cDNA synthesis, purification, fragmentation, and labeling were performed according to the microarray manufacturer’s instructions (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Microarray analysis

High-density custom microarrays based on the genome of P. putida KT2440 with additional probe sets were used for transcriptomics analysis (Wierckx et al. 2008; Ballerstedt et al. 2007). The end-labeled cDNA fragments were hybridized to the microarray according to standard manufacturer’s protocols. Hybridized microarrays were scanned by ServiceXS (Leiden, The Netherlands) on a high resolution Gene Chip Scanner 3000 7G system with autoloader (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) using standard default analysis settings (filter: 570 nm; pixel size: 2.5 μm). The resulting microarray data (.cel files) were imported into Genespring GX software package version 7.3.1 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) using the GC RMA algorithm. After normalization (signals below 0.01 were taken as 0.01; per chip: normalize to 50th percentile; per gene: normalize to specific sample), probesets representing intergenic regions and control genes were removed, as well as nonchanging genes (between 0.667- and 1.334-fold change). On the resulting set of differentially expressed genes a one-way ANOVA test (parametric test, p value of 0.05) was applied. Genes that were differentially expressed by at least a factor 2.5 were selected for further analysis.

Protein extraction

Protein extracts were prepared as described by Wijte et al. (Wijte et al. 2006). In brief, cells were boiled for 10 min in a Tris-SDS solution (0.2% SDS, 0.028 M Tris-HCl, 0.022 Tris-base, and 0.2 M DTT) and subsequently a DNase/RNase treatment was given. Proteins were then extracted by the methanol/chloroform method. The protein pellet was solubilized in a solution with 8-M urea, 4% CHAPS and 30 mM Tris and sonicated on ice (4 × 5 s). Protein concentrations were determined with the RC/DC assay (BioRad, Veenendaal, The Netherlands).

2D gel electrophoresis

Proteomics analysis was performed using the 2D-DIGE method, according to Volkers et al. (Volkers et al. 2006) and Wijte et al. (Wijte et al. 2006). Protein samples were labeled according to the manufacturers’ protocol (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden) with CyDyes Cy3 and Cy5. The standard sample, consisting of a mixture of equal amounts of all samples in the experiment, was labeled with Cy2. First dimension electrophoresis was performed according to the manufacturers’ protocol (GE Healthcare). In short, the labeled proteins were applied to a 24-cm Immobiline Dry-Strip pH 4–7 and rehydrated overnight or applied with cup-loading to a pre-hydrated 18-cm Dry-Strip pH 6–11. Iso-electric focusing was carried out using an IPGphor for a total of 60,750 Vh for the pH 4–7 strip and 30,750 Vh for the pH 6–11 strip. Prior to the second dimension electrophoresis, the strips were refocused for a total of 2,500 Vh. After that, the strips were incubated in equilibration buffer containing 1% (w/v) DTT for 15 min, followed by a 15-min incubation in equilibration buffer containing 2.5% (w/v) iodoacetamide. After equilibration, the strips were placed on top of 12.5% polyacrylamide lab-cast gels (pH 4–7) or 15% polyacrylamide lab-cast gels (pH 6–11) and sealed with a 1% agarose solution containing a trace of bromophenol blue. Gels were run for 1 h at 1 W per gel followed by 13 W per gel until the bromophenol blue had migrated to the bottom of the gel.

Image acquisition and data analysis

The gels were scanned using a Typhoon 9400 Imager at 100 µm resolution, according to the manufacturers’ protocol (GE Healthcare). Data analysis was performed using DeCyder 2D Software version 6.5 with the DeCyder Extended Data Analysis module version 1.0 (both GE Healthcare). After one-way analysis of variance (student’s t test with a p value of 0.05), significantly changed proteins were selected that had an average fold-change difference of at least 1.5 between the conditions tested.

In-gel digestion and protein identification

Preparative polyacrylamide gels were prepared following the protocol for analytical gels described above, with the following changes: only the Cy2-labeled standard was applied and after scanning the gels were stained with ProteomIQ Blue according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Proteome Systems, Woburn, MA, USA). After excision, the proteins spots were digested in-gel with trypsin, using the protocol described by Havlis et al. (Havlis et al. 2003). Protein identification was performed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry and microliquid chromatography electrospray tandem mass spectrometry, as described previously (Volkers et al. 2006).

Analytical methods

Cell densities were determined at 600 nm with an Ultrospec 10 cell density meter (GE Healthcare). An OD600 of 1 corresponds to 0.49 g l−1 of cell dry weight (CDW). The aromatic compounds were analyzed by HPLC (Agilent 1100 system) using a Zorbax 3.5 µm SB-C18 column (4.6 × 50 mm) and a diode-array detector. As the eluent, a linear gradient of acetonitrile in KH2PO4-buffer (50 mM, pH 2) with 1% acetonitrile was used, increasing from 0-25% in 4.9 min at a flow of 1.5 ml min−1. Glucose, gluconic acid and 2-ketogluconic acid were analyzed as described by Meijnen et al. (Meijnen et al. 2008). Glycerol was analyzed by ion chromatography (Dionex ICS3000 system), using an IonPac ICE AS1 column with 100 mM methyl sulphonic acid as the eluent at a flow of 1.2 ml min−1.

Targeted gene disruption

The previously employed gene replacement vectors pJQpobA::tetA (Verhoef et al. 2007) and pJQhpd::tetA (Wierckx et al. 2008) were modified by replacing the tetA marker by the same gene flanked by loxP recombination sites (Sauer and Henderson 1988; Sternberg and Hamilton 1981) yielding pJQpobA::tetAloxP and pJQhpd::tetAloxP (Table 1). For construction of the gene replacement vector pJQmfs::tetAloxP, two parts of the multidrug efflux MFS transporter genes (locus tag PP1271-PP1273) were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers NW23-NW26 (Table 2). The resulting PCR products mfs1 (5′ end) and mfs2 (3′ end) were digested with NotI/XbaI and XhoI/XbaI, respectively. Suicide plasmid pJQ200SK (Quandt and Hynes 1993) was digested with NotI and XhoI. The three resulting DNA fragments were ligated to yield pJQmfs. pJQmfs was linearized with XbaI and treated with bacterial alkaline phosphatase. The XbaI fragment from pSKtetlox (unpublished data) containing the loxP flanked tetA marker (Sauer and Henderson 1988; Sternberg and Hamilton 1981) was ligated into XbaI-digested pJQmfs yielding pJQmfs::tetAloxP.

Targeted gene disruptions were performed as described by Verhoef et al. (Verhoef et al. 2007). The loxP-flanked tetA marker was removed by site-specific recombination after introducing pJNTcre (unpublished data) and induction of the Cre recombinase with 0.1 mM Na-salicylate. Colonies that were tetracycline sensitive were selected and plasmid pJNTcre was removed by overnight culturing in non-selective Luria broth. Replacement of the native gene by the disrupted copy was confirmed by a colony PCR.

Construction of expression plasmids

Plasmid pBNTmcs(Gmr) was constructed as follows. The chloramphenicol (Cm) marker from pBBR1mcs (Kovach et al. 1995) was amplified by PCR using the primers Cm_F-AvaI and Cm_R_MluI (Table 2). The resulting fragment was ligated into the pJNTmcs (Meijnen et al. 2008) vector using the restriction sites MluI and Kpn2I (compatible with AvaI). From this vector, the salicylate-inducible NagR/pNagAa promoter, tac ribosomal binding site and Cm marker were amplified using primers RV165 and Cm_R_MluI (Table 2) and digested with Kpn2I and XmajI. The resulting fragment was ligated in a Kpn2I and XbaI (compatible with XmajI) digested pBBR1mcs vector, yielding pBNTmcs(Cmr). The Cm marker was replaced by a gentamicin (Gm) marker. The Gm marker of pJNNmcs (previously known as pTN-1 (Wierckx et al. 2005)) was obtained by PCR using primers KN34 and KN30 (Table 2) and cloned into the PagI and NcoI restriction sites of pBNTmcs(Cmr), yielding pBNTmcs(Gmr).

For constructing the MFS-transporter expression plasmid pBNTmfs(Gmr), the multidrug efflux MFS transporter (PP1271-PP1273) was amplified by PCR on genomic DNA of P. putida S12 using oligonucleotide primers KN48 and KN49 (Table 2). The resulting fragment was digested with KpnI and NotI and ligated into KpnI-NotI-digested pBNTmcs(Gmr).

Plasmid pJT’Tmcs was constructed by digesting pJTTmcs (Meijnen et al. 2008) with HindIII and BamHI and the resulting fragment was treated with S1 nuclease, according to manufacturer’s instructions. The nuclease treated vector was ligated, yielding pJT’Tmcs. For constructing pJT’Tpal, the pal gene was obtained from pJTTpal as a KpnI-NotI fragment and purified from agarose gel. The purified fragment was ligated into KpnI-NotI-digested pJT’Tmcs, yielding pJT’Tpal.

Results

General expression features of p-hydroxybenzoate producing P. putida S12palB1

P. putida S12palB1 was cultured in carbon limited chemostats with either glycerol or glucose as the carbon source. In agreement with previous observations (Verhoef et al. 2007), the carbon source had no major effect on product formation: on either substrate comparable concentrations of p-hydroxybenzoate and t-cinnamate were produced, at a similar product-to-substrate yield (Yps; Table 3). The biomass density as well as the biomass-to-substrate yield was slightly higher on glycerol (Table 3; data not shown). As control cultures, wild-type P. putida S12 variant strains were cultivated in chemostats and harbored either an empty expression plasmid (pJNNmcs(t); (Wierckx et al. 2008)), or the Pal/Tal expression plasmid (pJTTpal; Nijkamp et al. 2007; Table 3). Samples were drawn from the chemostat cultivations for transcriptomics and proteomics analysis. Comparisons were made between the optimized p-hydroxybenzoate producing strain P. putida S12palB1 and the non-optimized control strains, on either glucose or glycerol as the carbon source. Thus, the responses underlying the improved performance of the platform strain P. putida S12_427, as well as the impact of metabolic engineering on strain S12_427 to generate the p-hydroxybenzoate producing strain P. putida S12palB1 (Fig. 1), could be assessed for either carbon source.

Remarkably, the carbon source employed appeared to have a major effect on global transcript levels in the p-hydroxybenzoate producing P. putida S12palB1. With glucose as the carbon source, 215 genes were differentially expressed (fold change >2.5) in P. putida S12palB1 compared to the control strain, whereas only 88 genes were differentially expressed on glycerol. Proteome analysis showed a similar trend with 285 differentially expressed spots (fold change >1.5) in glucose-grown P. putida S12palB1 compared to the control strain, vs. 110 spots in the glycerol-grown cultures. From the glucose cultures, 93 out of the 285 spots were analyzed, representing 60 different proteins. Of the 110 differentially expressed spots of the glycerol cultures, 39 were analyzed representing 26 unique proteins.

The distribution of the differentially expressed genes and proteins over the different Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) categories (based on the NCBI-COG database of P. putida KT2440 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sutils/coxik.cgi?gi=266)) was very similar for glucose and glycerol-grown P. putida S12palB1 (Fig. 2a, b). Nearly all COG groups were represented. About one quarter of the differentially expressed genes and proteins were annotated as having a hypothetical (including unknowns) or general function only. Another 25% could be assigned to amino acid transport and metabolism. A similar response had been observed previously in the phenol-producing P. putida S12TPL3. This was proposed to relate to the selection procedure by which the parent strain P. putida S12_427 was obtained, i.e., resistance to fluoroanalogs of the amino acids phenylalanine and tyrosine (Wierckx et al. 2005). In addition, the COG groups of transcription and translation were well-represented, indicative of a substantial overall phenotypic difference between the p-hydroxybenzoate production strain and the control strain. The slight overrepresentation of the COG groups ‘energy production and conversion’ and ‘signal transduction’ were likely to relate to a solvent stress response, relating to the accumulation of p-hydroxybenzoate (Fig. 2; Park et al. 1998, 2001)).

Specific expression features of P. putida S12palB1 relating to p-hydroxybenzoate production

A number of differentially expressed genes and proteins in P. putida S12palB1 could be clearly linked to improved p-hydroxybenzoate production. These were classified into three functional groups: (1) aromatic amino acid biosynthesis and p-coumarate catabolism (i.e., the synthetic pathway of p-hydroxybenzoate biosynthesis), (2) aromatic amino acid catabolism, and (3) transport systems (Table 4; Fig. 3). A complete overview of differentially expressed genes and proteins is provided in Table 1 of the supplemental data.

Schematic overview of differentially expressed genes involved in relevant pathways of p-hydroxybenzoate biosynthesis, as derived from transcriptomics analysis of P. putida S12palB1. Gene names are indicated in italic or when absent, indicated by locus tags from P. putida KT2440. Red lines indicate upregulation and green lines indicate downregulation in P. putida S12palB1. The text boxes describe the proposed role in the enhanced p-hydroxybenzoate production of the differentially expressed genes

Aromatic amino acid biosynthesis and p-coumarate degradation

In P. putida S12palB1, five genes of the tyrosine biosynthetic pathway were upregulated, among which the aroF-1 gene that was present in an additional copy in this strain (Table 4). Moreover, the tryptophan biosynthetic pathway was found to be upregulated, both at the transcript level (trpCDGE) and at the protein level (TrpCDGE as well as TrpA; Table 4). These findings are in good agreement with previous results in phenol producing P. putida S12TPL3 (Wierckx et al. 2008) as well as with the improved p-hydroxybenzoate biosynthesis. The upregulation of the aromatic amino acid biosynthetic genes in general appeared to be somewhat lower on glycerol compared to glucose (by a factor 1.5–3). An exception was the dramatic effect observed for phhAB, the upregulation of which was lower by a factor 20–30 on glycerol-grown P. putida S12palB1 compared to glucose-grown cells.

In addition to the aromatic amino acid biosynthetic genes, all genes involved in the conversion of p-coumarate into p-hydroxybenzoate (Mitra et al. 1999; Jimenez et al. 2002; Venturi et al. 1998) were upregulated compared to the control strains (Table 4). Again, the level of upregulation of these genes was apparently carbon-source dependent, being lower by an order of magnitude in the glycerol-grown cells compared to the glucose-grown cultures.

Tyrosine degradation pathways

In addition to the tyrosine biosynthetic genes, genes involved in the degradation of tyrosine were upregulated (Table 4, Fig. 3), although exclusively in glucose-grown cultures. The tyrosine decarboxylase-encoding gene PP2552 was upregulated 48-fold in glucose-grown P. putida S12palB1. However, no accumulation of tyramine was observed. Considering that tyramine is a dead-end product, the contribution of tyrosine decarboxylase to tyrosine catabolism appeared to be limited. As suggested earlier for phenol-producing P. putida S12TPL3 (Wierckx et al. 2008), degradation of tyrosine is more likely to occur via the homogentisate pathway of which the upregulated hpd gene encodes the first enzyme, i.e., 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase.

Transport systems

The extracellular accumulation of p-hydroxybenzoate in cultures of P. putida S12palB1 is likely to involve cellular transport systems. This is supported by the upregulation of numerous transport systems in P. putida S12palB1 compared to the control strains. Among these were a multidrug efflux MFS transporter (PP1271–PP1273) and a wide range of (aromatic) amino acid transporters (Table 4). The nature of the carbon source employed apparently also affected the expression of these transporters. The upregulation of the MFS transporter genes PP1271–1273 showed little carbon-substrate dependency, being slightly lower on glycerol than on glucose. For the amino acid transporter-encoding genes, much larger upregulation was observed depending on the carbon source used. Remarkably at the protein level, even downregulation of some amino acid transporters was observed in glycerol-grown P. putida S12palB1 compared to the control strain, as opposed to the glucose-grown cultures (Table 4).

Improvement of p-hydroxybenzoate production by targeted deletion of the hpd gene

We previously demonstrated that the addition of tyrosine to chemostat-cultivated P. putida S12palB1 resulted in improved p-hydroxybenzoate titers, indicating that product formation was limited by the availability of tyrosine. However, part of the added tyrosine was consumed to generate biomass indicating that p-hydroxybenzoate production competed for tyrosine with other pathways (Verhoef et al. 2007). The upregulation of genes involved in tyrosine degradation as observed in the present study is in agreement with these observations. As argued above, tyrosine is probably mainly degraded via the homogentisate pathway. Therefore, the hpd gene was disrupted in P. putida S12palB1 to improve tyrosine availability.

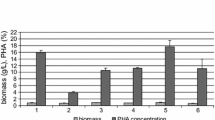

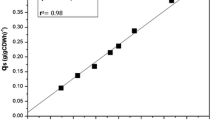

The resulting strain, P. putida S12palB2, showed a marked improvement of p-hydroxybenzoate production characteristics in shake flask cultures with glucose as the carbon source. Product titers increased from 1.8 to 2.3 mM compared to strain S12palB1, at a similar final biomass content (Fig. 4a, b). The Yps improved from 10.5 C-mol% for strain S12palB1 to 13.4 C-mol% for stain S12palB2, i.e., a relative yield improvement of 22%. Also, the productivity showed considerable improvement: the overall specific production rate qp increased from 1.6 to 2.3 μmol p-hydroxybenzoate (g CDW min)−1, while the maximum specific production rate (qp,max) increased from 3.8 to 4.4 μmol p-hydroxybenzoate (g CDW min)−1. Maximal qp was achieved between 10 and 12 h of cultivation, in line with the observed transient accumulation of p-coumarate (Fig. 4a, b). The latter is likely to relate to transient glucose repression of the fcs gene, which immediately affected the p-coumarate pool (Fig. 3).

Growth and production of p-hydroxybenzoate of P. putida S12palB1 (a), P. putida S12palB2 (b), P. putida S12palB3 (c), P. putida S12B3 (d), P. putida S12pal_mfsB3 (e) and P. putida S12pal_mfsB2 (f) in mineral medium with 20 mM glucose as carbon source in shake flask cultures. p-hydroxybenzoate (square), p-coumarate (triangle) and CDW (cell dry weight; diamond). The data are averages of triplicate experiments. The maximum variation between the triplicates was less than 10%

Interestingly, when P. putida S12palB2 was cultured on glycerol, p-hydroxybenzoate production was also improved. The product-to-substrate yield showed a relative increase of 21%, even though hpd was only slightly upregulated (below threshold of 2.5-fold) in glycerol-grown P. putida S12palB1. Transient accumulation of p-coumarate did not occur on glycerol since fcs was not repressed (unpublished data). Thus, disrupting the hpd gene clearly had a stimulating effect on p-hydroxybenzoate production.

Export of p-hydroxybenzoate in P. putida S12palB1

Transcriptome and proteome analysis in the present study showed extensive differential expression of cellular transport systems in P. putida S12palB1. Among the transporters identified, the multidrug efflux MFS transporter (P. putida KT2440 locus tags PP1271–PP1273) was upregulated on both glucose and glycerol, with only minor variation between the two carbon substrates. Since p-hydroxybenzoate accumulation was comparable in glucose and glycerol-grown cultures, the MFS transporter was considered as a putative p-hydroxybenzoate exporter in P. putida S12. To assess the role of this transporter in p-hydroxybenzoate transport, all three ORFs were deleted in P. putida S12palB2, yielding strain P. putida S12palB3. The inactivation of the MFS transporter resulted in slightly impaired growth and significantly lower p-hydroxybenzoate titers, although production was not completely eliminated (Fig. 4c). When the Pal/Tal expression plasmid pJTTpal was removed from P. putida S12palB3, resulting in the non-producing strain P. putida S12B3, normal growth was restored (Fig. 4d). Thus, the growth impairment observed in P. putida S12palB3 must be attributed to a combined effect of the transporter knock-out and intracellular p-hydroxybenzoate production.

Complementation of the MFS transporter in P. putida S12palB3 restored normal growth as well as production of p-hydroxybenzoate (Fig. 4e). These results suggest that the MFS transporter PP1271-1273 plays an important role in p-hydroxybenzoate export. Overexpression of the MFS transporter in P. putida S12palB2 did not result in improved p-hydroxybenzoate production (Fig. 4f). Since the complementation experiment indicated (Fig. 4e) that the MFS transporter was functionally expressed the MFS transporter clearly is not a limiting factor for p-hydroxybenzoate production.

Discussion

In the present study, the changes in transcript and protein levels underlying and affecting efficient p-hydroxybenzoate biosynthesis by P. putida S12palB1 have been studied. Many of the extensive general expression changes were found to relate to system-wide alterations originating from the optimization of the original platform strain (Verhoef et al. 2007; Wierckx et al. 2005; Wierckx et al. 2008). In addition, also p-hydroxybenzoate production appeared to have a substantial general impact. Part of the responses could be attributed to p-hydroxybenzoate stress, whereas others may be related to the ‘short-circuiting’ of an anabolic pathway (aromatic amino acid biosynthesis) and a catabolic pathway (p-coumarate degradation).

The pathways directly involved in p-hydroxybenzoate formation were considerably upregulated in P. putida S12palB1, in line with the elevated metabolic flux towards the product. These responses were comparable to those observed in P. putida S12TPL3 (Wierckx et al. 2008). The upregulation of the p-coumarate pathway is obviously unique for strain S12palB1 as this pathway requires the presence of p-coumaroyl-CoA for induction (Calisti et al. 2008). By contrast, no responses of the protocatechuate pathway were observed which is explained by the disruption of the first gene of this pathway, pobA, in P. putida S12palB1. The homogentisate pathway was shown to account for substantial loss of tyrosine, thus compromising p-hydroxybenzoate synthesis. Considerable improvement of both yield and productivity was achieved by targeted inactivation of hpd, the first gene of the homogentisate pathway.

Remarkably, the nature of the carbon source employed exerted major effects in P. putida S12palB1. Effects were observed both at the global expression level and specifically for genes and proteins that are directly associated with p-hydroxybenzoate biosynthesis and production. The effect was most prominent for the genes of the p-coumarate degradation pathway and the genes encoding phenylalanine hydroxylase, phhA and phhB. No such differences were observed between the control cultures on glucose and glycerol. Therefore, the carbon source-dependency of the expression of these genes must be considered a characteristic of P. putida S12palB1. Nonetheless, the transcript levels in glycerol-grown P. putida S12palB1 apparently sufficed to accommodate efficient p-hydroxybenzoate biosynthesis, since similar amounts were produced in glucose-grown and glycerol-grown cultures. Moreover, none of the upregulated ‘p-hydroxybenzoate biosynthetic’ gene products were detected in the proteomics analysis, which supported the notion that different transcript levels do not necessarily affect actual protein synthesis. It cannot be excluded, however, that the bottleneck for p-hydroxybenzoate production on either substrate is located upstream of the tyrosine biosynthetic pathway, e.g., at the level of the key aromatic precursors phosphoenolpyruvate and erythrose-4-phosphate.

In addition to metabolic genes, various transporter systems were differentially expressed in P. putida S12palB1. Although the multidrug efflux MFS transporter PP1271–PP1273 showed no similarity to known p-hydroxybenzoate transporters such as AaeAB of E. coli (Van Dyk et al. 2004), it was shown to be involved in p-hydroxybenzoate export. Overexpression did not improve production, however, suggesting that the innate transport capacity was sufficient to cope with the amount of p-hydroxybenzoate generated. The MFS transporter was furthermore not essential, and unlikely to be specific, for p-hydroxybenzoate export, since it was also upregulated in response to phenol (unpublished data), toluene (Volkers et al. 2008) and urea (in P. putida KT2440; (Reva et al. 2006)).

In addition to contributing to the general understanding of the genetic background underlying the improved p-hydroxybenzoate production characteristics of P. putida S12palB1, the transcriptomics and proteomics results provided leads that resulted in further strain improvement. Moreover, the fact that the available carbon source directly impacts the expression of key p-hydroxybenzoate biosynthetic pathways indicates that the p-hydroxybenzoate production capacity has not been exploited to its full potential. The precise nature of this upstream bottleneck preventing further yield improvement is currently under investigation.

References

Ballerstedt H, Volkers RJM, Mars AE, Hallsworth JE, Santos VA, Puchalka J, van Duuren J, Eggink G, Timmis KN, de Bont JAM, Wery J (2007) Genomotyping of Pseudomonas putida strains using P. putida KT2440-based high-density DNA microarrays: implications for transcriptomics studies. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 75:1133–1142

Calisti C, Ficca AG, Barghini P, Ruzzi M (2008) Regulation of ferulic catabolic genes in Pseudomonas fluorescens BF13: involvement of a MarR family regulator. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 80:475–483

Hartmans S, van der Werf MJ, de Bont JA (1990) Bacterial degradation of styrene involving a novel flavin adenine dinucleotide-dependent styrene monooxygenase. Appl Environ Microbiol 56:1347–1351

Havlis J, Thomas H, Sebela M, Shevchenko A (2003) Fast-response proteomics by accelerated in-gel digestion of proteins. Anal Chem 75:1300–1306

Jimenez JI, Minambres B, Garcia JL, Diaz E (2002) Genomic analysis of the aromatic catabolic pathways from Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ Microbiol 4:824–841

Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop RM 2nd, Peterson KM (1995) Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175–176

Meijnen JP, de Winde JH, Ruijssenaars HJ (2008) Engineering Pseudomonas putida S12 for efficient utilization of D-xylose and L-arabinose. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:5031–5037

Mitra A, Kitamura Y, Gasson MJ, Narbad A, Parr AJ, Payne J, Rhodes MJ, Sewter C, Walton NJ (1999) 4-hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA hydratase/lyase (HCHL)—an enzyme of phenylpropanoid chain cleavage from Pseudomonas. Arch Biochem Biophys 365:10–16

Nijkamp K, van Luijk N, de Bont JAM, Wery J (2005) The solvent-tolerant Pseudomonas putida S12 as host for the production of cinnamic acid from glucose. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 69:170–177

Nijkamp K, Westerhof RGM, Ballerstedt H, de Bont JAM, Wery J (2007) Optimization of the solvent-tolerant Pseudomonas putida S12 as host for the production of p-coumarate from glucose. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 74:617–624

Park S, Ko Y, Oh K, Kim C (1998) Cellular responses of Pseudomonas sp. DJ-12 to the stresses of several aromatic pollutants. J Microbiol 36:93–98

Park SH, Oh KH, Kim CK (2001) Adaptive and cross-protective responses of Pseudomonas sp. DJ-12 to several aromatics and other stress shocks. Curr Microbiol 43:176–181

Quandt J, Hynes MF (1993) Versatile suicide vectors which allow direct selection for gene replacement in Gram-negative bacteria. Gene 127:15–21

Reva ON, Weinel C, Weinel M, Bohm K, Stjepandic D, Hoheisel JD, Tummler B (2006) Functional genomics of stress response in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. J Bacteriol 188:4079–4092

Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T (1982) Molecular cloning. A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

Sauer B, Henderson N (1988) Site-specific DNA recombination in mammalian cells by the Cre recombinase of bacteriophage P1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 85:5166–5170

Sternberg N, Hamilton D (1981) Bacteriophage P1 site-specific recombination. I. Recombination between loxP sites. J Mol Biol 150:467–486

Van Dyk TK, Templeton LJ, Cantera KA, Sharpe PL, Sariaslani FS (2004) Characterization of the Escherichia coli AaeAB efflux pump: a metabolic relief valve? J Bacteriol 186:7196–7204

Venturi V, Zennaro F, Degrassi G, Okeke BC, Bruschi CV (1998) Genetics of ferulic acid bioconversion to protocatechuic acid in plant-growth-promoting Pseudomonas putida WCS358. Microbiology 144:965–973

Verhoef S, Ruijssenaars HJ, de Bont JA, Wery J (2007) Bioproduction of p-hydroxybenzoate from renewable feedstock by solvent-tolerant Pseudomonas putida S12. J Biotechnol 132:49–56

Verhoef S, Wierckx N, Westerhof RG, de Winde JH, Ruijssenaars HJ (2009) Bioproduction of p-hydroxystyrene from glucose by the solvent-tolerant bacterium Pseudomonas putida S12 in a two-phase water-decanol fermentation. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:931–936

Volkers RJ, de Jong AL, Hulst AG, van Baar BL, de Bont JA, Wery J (2006) Chemostat-based proteomic analysis of toluene-affected Pseudomonas putida S12. Environ Microbiol 8:1674–1679

Volkers RJ, Ballerstedt H, Ruijssenaars H, de Bont JA, de Winde JH, Wery J (2008) TrgI, toluene repressed gene I, a novel gene involved in toluene-tolerance in Pseudomonas putida S12. Extremophiles 13:283–297

Wierckx NJP, Ballerstedt H, de Bont JAM, Wery J (2005) Engineering of solvent-tolerant Pseudomonas putida S12 for bioproduction of phenol from glucose. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:8221–8227

Wierckx NJ, Ballerstedt H, de Bont JA, de Winde JH, Ruijssenaars HJ, Wery J (2008) Transcriptome analysis of a phenol-producing Pseudomonas putida S12 construct: genetic and physiological basis for improved production. J Bacteriol 190:2822–2830

Wierckx N, Ruijssenaars HJ, de Winde JH, Schmid A, Blank LM (2009) Metabolic flux analysis of a phenol producing mutant of Pseudomonas putida S12: verification and complementation of hypotheses derived from transcriptomics. J Biotechnol 143:124–129

Wijte D, de Jong AL, Mol MA, van Baar BL, Heck AJ (2006) ProteomIQ blue, a potent post-stain for the visualization and subsequent mass spectrometry based identification of fluorescent stained proteins on 2D-gels. J Proteome Res 5:2033–2038

Acknowledgments

We thank Karin Nijkamp for the construction of the pBNTmfs(Gmr) vector and Nick Wierckx for the construction of the suicide vectors pJQhpd::tetAloxP and pJQmfs::tetAloxP. This project is financially supported by the Netherlands Ministry of Economic Affairs and the B-Basic partner organizations (www.b-basic.nl) through B-Basic, a public-private NWO-ACTS program (Advanced Chemical Technologies for Sustainability, ACTS). This project was co-financed by the Kluyver Centre for Genomics of Industrial Fermentation, which is part of the Netherlands Genomics Initiative/Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Table 1

Supplemental data: full score of genes and proteins that were differentially expressed in P. putida S12palB1 compared to the control strain (DOC 538 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Verhoef, S., Ballerstedt, H., Volkers, R.J.M. et al. Comparative transcriptomics and proteomics of p-hydroxybenzoate producing Pseudomonas putida S12: novel responses and implications for strain improvement. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 87, 679–690 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-010-2626-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-010-2626-z