Abstract

Background

During the past 15 years, opioid-related overdose death rates for women have increased 471%. Many surgeons provide opioid prescriptions well in excess of what patients actually use. This study assessed a health systems intervention to control pain adequately while reducing opioid prescriptions in ambulatory breast surgery.

Methods

This prospective non-inferiority study included women 18–75 years of age undergoing elective ambulatory general surgical breast procedures. Pre- and postintervention groups were compared, separated by implementation of a multi-pronged, opioid-sparing strategy consisting of patient education, health care provider education and perioperative multimodal analgesic strategies. The primary outcome was average pain during the first 7 postoperative days on a numeric rating scale of 0–10. The secondary outcomes included medication use and prescription renewals.

Results

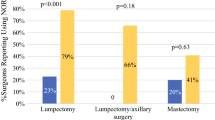

The average pain during the first 7 postoperative days was non-inferior in the postintervention group despite a significant decrease in median oral morphine equivalents (OMEs) prescribed (2.0/10 [100 OMEs] pre-intervention vs 2.1/10 [50 OMEs] post-intervention; p = 0.40 [p < 0.001]). Only 39 (44%) of the 88 patients in the post-intervention group filled their rescue opioid prescription, and 8 (9%) of the 88 patients reported needing an opioid for additional pain not controlled with acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) postoperatively. Prescription renewals did not change.

Conclusion

A standardized pain care bundle was effective in minimizing and even eliminating opioid use after elective ambulatory breast surgery while adequately controlling postoperative pain. The Standardization of Outpatient Procedure Narcotics (STOP Narcotics) initiative decreases unnecessary and unused opioid medication and may decrease risk of persistent opioid use. This initiative provides a framework for future analgesia guidelines in ambulatory breast surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, Parrino MW, Severtson SG, Bucher-Bartelson B, Green JL. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:241–8. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa1406143.

Government of Canada–Health Canada. National report: apparent opioid-related deaths in Canada. 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2018 at https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/apparent-opioid-related-deaths-report-2016-2017-december.html.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Final report: opioid use, misuse, and overdose in women. 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2018 at https://www.womenshealth.gov/files/documents/final-report-opioid-508.pdf.

Hill MV, McMahon ML, Stucke RS, Barth RJ. Wide variation and excessive dosage of opioid prescriptions for common general surgical procedures. Ann Surg. 2017;265:709–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000001993.

Marcusa DP, Mann RA, Cron DC, et al. Prescription opioid use among opioid-naive women undergoing immediate breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140:1081–90. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000003832.

Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:e170504. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504.

Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1286. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3298.

Carmichael A-N, Morgan L, Del Fabbro E. Identifying and assessing the risk of opioid abuse in patients with cancer: an integrative review. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2016;7:71–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/sar.s85409.

Lee JS-J, Hu HM, Edelman AL, et al. New persistent opioid use among patients with cancer after curative-intent surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:4042–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2017.74.1363.

Afonso AM, Newman MI, Seeley N, et al. Multimodal analgesia in breast surgical procedures: technical and pharmacological considerations for liposomal bupivacaine use. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5:e1480. https://doi.org/10.1097/gox.0000000000001480.

Gärtner R, Kroman N, Callesen T, Kehlet H. Multimodal prevention of pain, nausea, and vomiting after breast cancer surgery. Minerva Anestesiol. 2010;76:805–13.

Kumar K, Kirksey MA, Duong S, Wu CL. A review of opioid-sparing modalities in perioperative pain management. Anesth Analg. 2017;125:1749–60. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000002497.

Elvir-Lazo OL, White PF. The role of multimodal analgesia in pain management after ambulatory surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2010;23:697–703. https://doi.org/10.1097/aco.0b013e32833fad0a.

Offodile AC, Gu C, Boukovalas S, Coroneos CJ, Chatterjee A, Largo RD, Butler C. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathways in breast reconstruction: systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4991-8.

Fassoulaki A, Triga A, Melemeni A, Sarantopoulos C. Multimodal analgesia with gabapentin and local anesthetics prevents acute and chronic pain after breast surgery for cancer. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1427–32. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ane.0000180200.11626.8e.

Karmakar MK, Samy W, Li JW, Lee A, WC Chan, Chen PP, Ho AMH. Thoracic paravertebral block and its effects on chronic pain and health-related quality of life after modified radical mastectomy. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2014;39:289–98. https://doi.org/10.1097/aap.0000000000000113.

Gómez-Hernández J, Orozco-Alatorre AL, Domínguez-Contreras M, et al. Preoperative dexamethasone reduces postoperative pain, nausea, and vomiting following mastectomy for breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:692. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-692.

Correll DJ, Viscusi ER, Grunwald, Z, Moore JHJ. Epidural analgesia compared with intravenous morphine patient-controlled analgesia: postoperative outcome measures after mastectomy with immediate TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2001;26:444–9.

Chang YC, Liu CL, Liu TP, Yang PS, Chen MJ, Cheng SP. Effect of perioperative intravenous lidocaine infusion on acute and chronic pain after breast surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Pract. 2017;17:336–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/papr.12442.

Scully RE, Schoenfeld AJ, Jiang W, et al. Defining optimal length of opioid pain medication prescription after common surgical procedures. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:37. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3132.

Lee JS, Howard RA, Klueh MP, et al. The impact of education and prescribing guidelines on opioid prescribing for breast and melanoma procedures. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018 https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-6772-3.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC’s response to the opioid overdose epidemic. 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018 at https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/strategy.html.

Health Canada. Joint statement of action to address the opioid crisis: a collective response. 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2018 at http://www.ccsa.ca/ResourceLibrary/CCSA-Joint-Statement-of-Action-Opioid-Crisis-Annual-Report-2017-en.pdf.

Breast Care Program/St. Joseph’s Health Care London. 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2018 at https://www.sjhc.london.on.ca/breastcare.

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observation Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE). 2007. Retrieved 7 July 2019 at https://www.strobestatement.org/fileadmin/Strobe/uploads/checklists/STROBE_checklist_v4_cohort.pdf.

Hartford LB, Van Koughnett JAM, Murphy PB, et al. Standardization of Outpatient Procedure (STOP) Narcotics: a prospective non-inferiority study to reduce opioid use in outpatient general surgical procedures. J Am Coll Surg. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.09.008.

Krebs EE, Carey TS, Weinberger M. Accuracy of the pain numeric rating scale as a screening test in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1453–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0321-2.

Jensen MP, Karoly P. Self-report scales and procedures for assessing pain in adults—PsycNET. 1992. Retrieved 1 May 2019 at https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1992-98469-004.

Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM, Fisher LD. Comparative reliability and validity of chronic pain intensity measures. Pain. 1999;83:157–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00101-3.

Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain, Numeric Rating Scale for Pain, McGill Pain Questionnaire, Short Form: McGill Pain Questionnaire, Chronic Pain Grade Scale, Short Form-36: Bodily Pain Scale, measure of intermittent and constant osteoarthritis pain. Arthritis Care Res 2011;63:240–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20543.

Keller S, Bann CM, Dodd SL, Schein J, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Validity of the brief pain inventory for use in documenting the outcomes of patients with noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:309–18.

Gerbershagen HJ, Rothaug J, Kalkman CJ, Meissner W. Determination of moderate-to-severe postoperative pain on the numeric rating scale: a cutoff point analysis applying four different methods. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107:619–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aer195.

IBM Corp. IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, released 2016, version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Sugai DY, Deptula PL, Parsa AA, Don Parsa F. The importance of communication in the management of postoperative pain. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2013;72:180–4.

Hill MV, Stucke RS, McMahon ML, Beeman JL, Barth RJ. An educational intervention decreases opioid prescribing after general surgical operations. Ann Surg. 2018;267:468–472. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000002198.

Wetzel M, Hockenberry J, Raval MV. Interventions for postsurgical opioid prescribing. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:948. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2730.

Meisenberg BR, Grover J, Campbell C, Korpon D. Assessment of opioid prescribing practices before and after implementation of a health system intervention to reduce opioid overprescribing. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:e182908. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2908.

Howard R, Waljee J, Brummett C, Englesbe M, Lee J. Reduction in opioid prescribing through evidence-based prescribing guidelines. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:285. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4436.

Chiu C, Aleshi P, Esserman LJ, Inglis-Arkell C, Yap E, Whitlock EL, Harbell MW. Improved analgesia and reduced postoperative nausea and vomiting after implementation of an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for total mastectomy. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018;18:41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-018-0505-9.

Rojas KE, Manasseh DM, Flom PL, Agbroko S, Bilbro N, Andaz C, Borgen PI. A pilot study of a breast surgery enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol to eliminate narcotic prescription at discharge. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;171:621–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4859-y.

Arsalani-Zadeh R, Elfadl D, Yassin N, MacFie J. Evidence-based review of enhancing postoperative recovery after breast surgery. Br J Surg. 2011;98:181–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.7331.

Sekhri S, Arora NS, Cottrell H, et al. Probability of opioid prescription refilling after surgery: does initial prescription dose matter? Ann Surg. 2018;268:271–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000002308.

Waljee JF, Li ÃL, Brummett CM, Englesbe MJ. Iatrogenic opioid dependence in the United States: are surgeons the gatekeepers? Ann Surg. 2017;265:728–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000001904.

Fujii MH, Hodges AC, Russell RL, et al. Post-discharge opioid prescribing and use after common surgical procedure. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226:1004–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.01.058.

Tan WH, Yu J, Feaman S, et al. Opioid medication use in the surgical patient: an assessment of prescribing patterns and use. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;227:203–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.04.032.

Feinberg AE, Chesney TR, Srikandarajah S, Acuna SA, McLeod RS. Opioid use after discharge in postoperative patients: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2018;267:1056–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000002591.

Andersen L, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kristensen BB, Husted H, Otte KS, Kehlet H. Subacute pain and function after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:508–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05831.x.

Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:17–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aen103.

Derry CJ, Derry S, Moore RA. Single-dose oral ibuprofen plus paracetamol (acetaminophen) for acute postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd010210.pub2.

Derry S, Derry CJ, Moore RA. Single-dose oral ibuprofen plus oxycodone for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd010289.pub2.

Overton HN, Hanna MN, Bruhn WE, et al. Opioid-prescribing guidelines for common surgical procedures: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;227:411–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.07.659.

Reddy A, de la Cruz M, Rodriguez EM, et al. Patterns of storage, use, and disposal of opioids among cancer outpatients. Oncologist. 2014;19:780–5. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0071.

Hasak JM, Bettlach CLR, Santosa KB, Stroud J, Mackinnon SE, Larson EL. Empowering post-surgical patients to improve opioid disposal: a before and after quality improvement study. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226:235–40.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.023.

Gärtner R, Jensen M-B, Nielsen J, Ewertz M, Kroman N, Kehlet H. Prevalence of and factors associated with persistent pain following breast cancer surgery. JAMA. 2009;302:1985. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1568.

Katz J, Poleshuck EL, Andrus CH, Hogan LA, Jung BF, Kulick DI, Dworkin RH. Risk factors for acute pain and its persistence following breast cancer surgery. Pain. 2005;119:16–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.008.

Singh S, Clarke C, Lawendy AR, Macleod M, Sanders D, Tieszer C. A prospective, randomized controlled trial of the impact of written discharge instructions for postoperative opioids on patient pain satisfaction and on minimizing opioid risk exposure in orthopaedic surgery. Curr Orthop Pract. 2018;29:292–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/bco.0000000000000632.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge Samuel Gray, BSc, and Carlos Garcia-Ochoa, MD, who were involved in data collection for this study. We also acknowledge Dr. Ken Leslie MD, MHPE, FRCSC, who was instrumental in the study design as well as ongoing feedback and input throughout the study. Dr. Supriya Singh and the orthopedic surgery team at London Health Sciences Centre also provided study motivation and guidance stemming from their recent randomized control trial involving written instructions and opioid use in orthopedic surgery at our institution.56

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

There are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Multi-pronged Opioid-Sparing Intervention

Patient Education

Patients were educated by staff, residents, and nurses through written instructions (standardized education sheets) and verbal reinforcement on two occasions: the initial surgical consultation and the day of surgery. Patients’ expectations surrounding the surgery, discomfort, and the recovery process were clarified. Instructions focused on optimal use of non-opioid analgesic medications (acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and conservative measures such as ice therapy. Patients were instructed only to fill a separate rescue 10-tablet opioid prescription if their discomfort was not satisfactorily controlled by other measures. Finally, patients were educated on appropriate medication disposal.

Provider Education

Surgeons, anesthetists, residents, post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) nurses and pre-admission clinic (PAC) staff were educated through divisional rounds, meetings, and emails. This education focused on current evidence surrounding opioid use and prescribing after surgery, as well as the development and commencement of the Standardization of Outpatient Procedure Narcotics (STOP Narcotics) initiative.

Intraoperative Protocol

Concerning the surgical safety checklist, it was reinforced with the anesthetist that patients were to receive ketorolac (15–30 mg IV), ondansetron (4–8 mg IV), and dexamethasone (4–8 mg IV) during the surgery. All surgeons were encouraged to use local anesthetic field blocks (lidocaine or bupivacaine).

Postoperative Protocol

Patients received a prescription for an NSAID (meloxicam 7.5 mg or naproxen 400 mg) to be taken twice daily for 72 h. Acetaminophen 500 mg also was to be taken every 6 h for 72 h. After 72 h, patients were instructed to take ibuprofen 400 mg and acetaminophen 500 mg as needed. A separate rescue prescription of 10 tablets of an opioid prescription was provided (tramadol 50 mg or codeine 30 mg). This prescription expired in 7 days, with instructions to fill it only if discomfort was not sufficiently achieved through other analgesic and conservative measures. Ice therapy also was used at the discretion of the surgeon and patient.

Appendix 2: Postoperative Pain Management Instructions

Patients were asked to notify their surgeon if they had a history of stomach ulcers, liver disease, kidney disease, or allergies to any of these medications.

Ice therapy was suggested to help reduce swelling and discomfort at the surgical site during the acute postoperative period. Patients were instructed that an ice pack wrapped in a cloth may be applied to the breast and/or axilla for the first couple of days after surgery. This was recommended for 15 min/15 min off at a time.

First 3 days (72 h) After Surgery

-

1.

Meloxicam 7.5 mg: 1 tablet PO, q12 h, for 3 days (prescription)

-

2.

Acetaminophen 500 mg; 1–2 tablets PO q6 h, for 3 days.

If the patient does not have coverage for meloxicam, the following may be prescribed:

-

1.

Naproxen 200 mg (Aleve): take 2 tablets orally every 12 h for 3 days.

To maximize pain relief, it was strongly recommended to take both of these medications.

After 3 days (72 h) After Surgery

-

1.

Continue acetaminophen 500 mg: 1–2 tablets PO q6 h as needed

-

2.

Ibuprofen 400 mg; 1 tablet PO q6 h as needed.

Patients are given separate prescriptions with the following instructions:

Tramadol 50 mg: 1 tablet PO q6 h PRN (10 tabs) (expiration date 7 days)

If the patient does not have coverage for tramadol, the following may be prescribed:

Codeine 30 mg: 1 tab PO q6 h PRN (10 tablets) (expiration date 7 days)

Patients were given instructions to fill this prescription only if the aforementioned measures do not adequately control their pain.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hartford, L.B., Van Koughnett, J.A.M., Murphy, P.B. et al. The Standardization of Outpatient Procedure (STOP) Narcotics: A Prospective Health Systems Intervention to Reduce Opioid Use in Ambulatory Breast Surgery. Ann Surg Oncol 26, 3295–3304 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-019-07539-w

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-019-07539-w