Abstract

Background

The body mass index (BMI) in the general population has increased over the past decades. A high BMI is a known risk factor for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Several studies on the influence of a high BMI on the postoperative course and survival after esophagectomy have shown contradictory results. The aim of the present study was to determine the influence of a high BMI on postoperative complications and survival among a large cohort of esophageal cancer patients.

Methods

Patients who underwent an esophagectomy between 1993 and 2010 were divided into three groups according to their BMI: normal weight (<25 kg/m2), overweight (25–30 kg/m2) or obese (≥30 kg/m2). Severity of complications was scored according to the Dindo classification, which was divided into three categories: no complications, minor to moderate complications, and severe complications. Long-term survival was determined according to the Kaplan–Meier method.

Results

A total of 736 esophagectomy patients were divided into three groups: normal weight (n = 352), overweight (n = 308), and obese (n = 72). Complications rates were similar for all groups (65–72%, P = 0.241). The incidence of anastomotic leakage was higher among obese patients compared to the other groups (20% vs. 10–12% respectively, P = 0.019), but there was no significant difference between the three groups regarding the severity of complications according to the Dindo classification (P = 0.660) or in 5-year survival rates (P = 0.517).

Conclusions

A high BMI is not associated with an increased incidence or severity of complications after esophagectomy; however, anastomotic leakage occurred more frequently in obese patients. Five-year survival rates were not influenced by the preoperative BMI. A high BMI is therefore ought not be an exclusion criterion for esophagectomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the Western world, together with the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma, the incidence of high body mass index (BMI) has greatly increased over the past decades.1 A high BMI is a known risk factor for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma; it is related to a higher incidence of gastroesophageal reflux which is strongly related to the risk for Barrett esophagus.2 During the last few decades, the proportion of overweight esophageal cancer patients has been rising.3 Substantial overweight and obesity are associated with an increased incidence of cardio respiratory morbidity; therefore, anesthesia and surgery can be hazardous in these patients.4 Moreover, surgery in obese patients can be troublesome, requiring lengthy surgery and increased blood loss. Consequently, it has been concluded that the rate of postoperative complications in obese patients is higher.5

Various studies have evaluated the postoperative outcome after an esophagectomy in patients with a high BMI compared to patients of average weight. Several studies describe no differences in postoperative complications after an esophagectomy in overweight or obese patients compared to patients with a BMI of <25 kg/m2.6–8 Some studies, however, report a higher incidence of severe complications or an increased rate of respiratory and gastrointestinal complications in patients with obesity.9–11 The severity of complications is unspecified in these studies, and because no standardized classification of severity of complications was used, morbidity ranges from urinary tract infections to postoperative mortality. The large variation in severity of complications makes comparison of the previously mentioned studies difficult.

The influence of a high BMI on long-term survival has also been investigated, again with contradictory results. Some authors describe an improved overall and disease-free survival rate in obese patients, while others report no marked differences compared to patients with a normal BMI.6,7,9–11

On the basis of the current results, it is not clear whether a high BMI influences the postoperative outcome and long-term survival after an esophagectomy. Therefore, the relation between a high BMI and the severity of postoperative complications was evaluated according to a validated standard classification according to Dindo et al.12 Furthermore, survival in esophageal carcinoma patients was evaluated in the present study.

Methods

Patients

All esophageal cancer patients who underwent surgical resection at the Academic Medical Centre between January 1993 and December 2010 were included in this study. At the first visit to the outpatient clinic, patient weight and length were measured, and BMI was calculated according to the World Health Organization criteria.13 Patients were divided into three groups according to their BMI: normal weight (<25 kg/m2), overweight (25–30 kg/m2), or obese (≥30 kg/m2). There were only 48 patients with a BMI of <20 kg/m2 and 15 patients with a BMI of >35 kg/m2. It was not possible to perform a separate statistical analysis with these small groups.

Patients who underwent neoadjuvant therapy or patients of whom the preoperative BMI was unknown were excluded from analyses (Fig. 1). Data, including patient characteristics, tumor stage, histopathologic features, and postoperative complications, were collected and entered into a prospectively monitored database.

Surgery

Surgical resection was performed by conventional open transthoracic or transhiatal esophagectomy, as previously described in studies from our center.14 In brief, transhiatal esophagectomy was performed with dissection of the esophagus under direct vision through the widened hiatus of the diaphragm up to the inferior pulmonary vein. The tumor and its adjacent lymph nodes were dissected en bloc, as were the paracardial, lesser curvature, left gastric artery, celiac trunk, common hepatic artery, and splenic artery nodes. A 3-cm-wide gastric tube was constructed, and after left-sided mobilization of the cervical esophagus, the intrathoracic esophagus was bluntly stripped from the neck to the upper level of the inferior pulmonary vein with a large vein stripper.

Transthoracic esophagectomy included a two-field lymphadenectomy. Along with the esophagus, the middle mediastinal, subcarinal, and right-sided paratracheal lymph nodes were dissected en bloc. Lymph node dissection was performed in a manner identical to the transhiatal approach, as was the construction of the gastric tube.

Pathologic tumor stage was determined according to the 6th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer.15

Definition of Complications

The severity of postoperative complications was graded according to the classification system composed by Dindo et al.12 This system is based on the therapeutic consequences of complications and consists of five grades. Grade I complications do not need any medical or surgical intervention, grade II complications require pharmacological treatment, grade III complications need radiological (IIIa) or surgical (grade IIIb) intervention, and grade IV complications are life-threatening and represent single-organ (grade IVa) or multiorgan (grade IVb) dysfunction (Table 1). Grade V complications are complications leading to death. Grading of complications was performed according to the most severe complication in each patient by a panel of four contributing authors (R.B., S.L., M.v.B.H., and O.B.). In a previous study performed at our institute, three categories of complications were defined: no complications (category 0), minor to moderate complications (category 1, grade I to IIIb), and severe complications (category 2, grade IVa, IVb and V).16 For the purpose of the present study, the same categories were used.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical calculations were performed by SPSS software, version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Differences between groups were tested by the Mann-Whitney U-test for continuous data. Differences between three groups were tested by the Kruskal-Wallis test. The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was performed to compare proportions. Survival analysis was performed by Kaplan–Meier curves with log rank tests for significance. A two-sided P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

After exclusion of 372 patients who underwent neoadjuvant therapy or had an unknown BMI, the remaining 736 patients were divided into three groups according to BMI (Fig. 1).

Patient characteristics are listed in Table 2. Patients with a normal weight were less likely to have a history of cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus compared to patients with overweight or obesity (P ≤ 0.001 and P = 0.021, respectively). Furthermore, adenocarcinomas were more frequently diagnosed in patients with a BMI of >25 kg/m2 (84–88%, P = 0.023).

Surgical Characteristics

Most patients in all three groups underwent transhiatal esophagectomy (Table 3). The median duration of surgery was 4.5 h in patients with a normal weight or obesity, and 5 h in overweight patients (P = 0.857). There was no statistically significant difference in perioperative blood loss (median 1100 ml).

Pathology

A radical resection was achieved in more than 80% of patients in all BMI classes, and pathologic stage was similar for all groups regardless of BMI (Table 3). There was no statistically significant difference in the median number of collected lymph nodes between the different BMI classes (normal weight, n = 18; overweight, n = 19; obese, n = 19; P = 0.675), or in the lymph node ratio (normal weight 0.096, overweight 0.096, and obese 0.076, P = 0.906).

Postoperative Complications

Anastomotic leakage occurred in 20% of patients with obesity compared to 10% and 12% in patients with normal weight or overweight (P = 0.019). Chylous leakage was more frequently present in patients with a BMI of <25 kg/m2 (P = 0.030). Overall complications and in-hospital mortality were comparable for all groups.

When all postoperative complications were categorized according to the Dindo classification, there were no significant differences between patients with normal weight, overweight, or obesity (P = 0.660). In more than 25% of patients, there were no postoperative complications, regardless of BMI. The percentage of patients who developed severe complications varied from 18% to 22% of patients between the different BMI groups (Table 4).

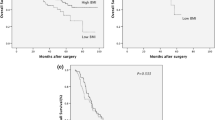

Survival

Median survival was 23 months (range, 0–190 months). Overall 5-year survival was 34.8%, whereas cancer-specific 5-year survival was 36.7%. There was no significant difference in cancer-specific 5-year survival between the different BMI classes (normal weight 36.4%, overweight 36.0%, and obesity 39.3%, P = 0.517).

Neoadjuvant Therapy

To ensure a homogeneous group, neoadjuvantly treated patients were excluded. However, because preoperative therapy is currently the standard treatment for patients with locoregional esophageal carcinoma, we performed an analysis on postoperative complications according to the Dindo classification and a survival analysis among these 286 patients.17,18 Neoadjuvantly treated patients were subdivided into the same BMI classes as patients who underwent surgery alone. There were no significant differences in Dindo classification (P = 0.233) or overall 5-year survival (P = 0.962) among the different neoadjuvantly treated BMI classes.

Discussion

In the present study, the severity of complications according to the Dindo classification and long-term survival were not statistically different among the individual BMI classes. Anastomotic leakage occurred more frequently in obese patients but was not associated with a higher incidence of grade IV and V therapeutic interventions. Subgroup analysis among 286 neoadjuvantly treated patients showed no statistically significant differences in postoperative outcome or long-term survival among the different BMI classes.

In a previous study from our center, a BMI of >27 kg/m2 proved to be an independent risk factor for the development of anastomotic leakage.19 A higher rate of anastomotic leakage among obese esophageal cancer patients has been reported in previous studies, and this finding is confirmed by our results.9,11 A possible explanation could be the higher incidence of diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease among obese patients in general, which were also present in our overweight patient group. Diabetes mellitus is correlated to impaired wound healing, which can lead to anastomotic leakage.20 It has also been speculated that anastomotic leakage in patients with a high BMI is due to a compromised vascularity of the conduit because of an increased tension on the conduit in the thoracic compartment.9 Furthermore, performing a cervical anastomosis, which was the standard in the present series, can be challenging in obese patients.

Previous studies on esophageal cancer patients with a high BMI have shown contradictory results regarding the postoperative course, varying from no differences in postoperative complications to a higher incidence of severe complications in obese patients.6,8–11 In accordance with our results, these studies report that adenocarcinomas occur more frequently than squamous cell carcinomas in patients with a high BMI, and that the incidence of diabetes mellitus is higher among obese patients.6,9–11

The severity of complications was reported in only one other study by Grotenhuis et al.9 In this series, severe complications occurred more frequently among patients with obesity, although the definition of “severe” was not clarified. Therefore, it is not possible to compare their results with the present study.

In contrast to previous studies, we did not find any differences in gastrointestinal or respiratory complications among the different BMI classes.10,11 This may be due to a discrepancy in definitions, which is why we graded complications according to the Dindo classification.

The perception that surgery in obese patients leads to technical challenges, and therefore lengthy surgery with increased perioperative blood loss, was not confirmed by our results; there were no statistically significant differences compared to patients with a normal weight. Equally, the number of collected lymph nodes among obese patients was similar to that in patients with a normal weight.

In the present study, there were no statistically significant differences in 5-year cancer-specific survival among the different BMI classes. This is in accordance with most other studies on BMI in esophageal cancer patients.7,9,11 Only two studies reported an improved survival rate in obese patients.6,10 In these studies, findings are explained by the lower baseline clinical stage in patients with a high BMI. In the present study, there was no difference in preoperative clinical stage among the different BMI classes.

Although this study did not show any differences amongst the different BMI classes regarding postoperative complications and long-term survival, we were not able to evaluate malnourished patients (BMI <25 kg/m2) or severely obese patients (BMI >35 kg/m2) because the numbers of these patients were too small. Further research should be performed focusing on these specific patient groups.

In conclusion, a high BMI in esophageal cancer patients is not associated with an increased incidence of postoperative complications or an impaired long-term survival after esophagectomy, although anastomotic leakage occurred more frequently among patients with a BMI of >25 kg/m2. Therefore, patients should not be excluded from potentially curative esophagectomy on the basis of a high BMI alone but merely judged on comorbidity to choose the optimal treatment modality.

References

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–41.

Lundell LR. Etiology and risk factors for esophageal carcinoma. Dig Dis. 2010;28:641–4.

van Heijl M, van Lanschot JJ, Blom RL, et al. [Outcomes of 16 years of oesophageal surgery: low postoperative mortality and improved long-term survival]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2010;154:A1156.

Adams JP, Murphy PG. Obesity in anaesthesia and intensive care. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:91–108.

Fujitani K, Ajani JA, Crane CH, et al. Impact of induction chemotherapy and preoperative chemoradiotherapy on operative morbidity and mortality in patients with locoregional adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2010–7.

Melis M, Weber JM, McLoughlin JM, et al. An elevated body mass index does not reduce survival after esophagectomy for cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:824–31.

Morgan MA, Lewis WG, Hopper AN, et al. Prognostic significance of body mass indices for patients undergoing esophagectomy for cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:29–35.

Scipione CN, Chang AC, Pickens A, et al. Transhiatal esophagectomy in the profoundly obese: implications and experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:376–82.

Grotenhuis BA, Wijnhoven BP, Hotte GJ, et al. Prognostic value of body mass index on short-term and long-term outcome after resection of esophageal cancer. World J Surg. 2010;34:2621–7.

Hayashi Y, Correa AM, Hofstetter WL, et al. The influence of high body mass index on the prognosis of patients with esophageal cancer after surgery as primary therapy. Cancer. 2010;116:5619–27.

Healy LA, Ryan AM, Gopinath B, et al. Impact of obesity on outcomes in the management of localized adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134:1284–91.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13.

World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation on obesity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000.

Hulscher JB, van Sandick JW, de Boer AG, et al. Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1662–9.

Green FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al. AJCC cancer staging handbook. Philadelphia: Lippincott Raven; 2002.

Lagarde SM, Reitsma JB, Maris AK, et al. Preoperative prediction of the occurrence and severity of complications after esophagectomy for cancer with use of a nomogram. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:1938–45.

Gaast AV, van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, et al. Effect of preoperative concurrent chemoradiotherapy on survival of patients with resectable esophageal or esophagogastric junction cancer: results from a multicenter randomized phase III study. Presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting, Chicago, IL, 2010.

Gebski V, Burmeister B, Smithers BM, et al. Survival benefits from neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy or chemotherapy in oesophageal carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:226–34.

van Heijl M, van Wijngaarden AK, Lagarde SM, et al. Intrathoracic manifestations of cervical anastomotic leaks after transhiatal and transthoracic oesophagectomy. Br J Surg. 2010;97:726–31.

Wright CD, Kucharczuk JC, O’Brien SM, et al. Predictors of major morbidity and mortality after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: a Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database risk adjustment model. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:587–95.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Blom, R.L.G.M., Lagarde, S.M., Klinkenbijl, J.H.G. et al. A High Body Mass Index in Esophageal Cancer Patients Does Not Influence Postoperative Outcome or Long-Term Survival. Ann Surg Oncol 19, 766–771 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-011-2103-7

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-011-2103-7