Abstract

Crystallographic image processing (CIP) techniques may be utilized in scanning probe microscopy (SPM) to glean information that has been obscured by signals from multiple probe tips. This may be of particular importance for scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) and requires images from samples that are periodic in two dimensions (2D). The image-forming current for double-tips in STM is derived with a slight modification of the independent-orbital approximation (IOA) to allow for two or more tips. Our analysis clarifies why crystallographic averaging works well in removing the effects of a blunt STM tip (that consists of multiple mini-tips) from recorded 2D periodic images and also outlines the limitations of this image-processing technique for certain spatial separations of STM double-tips. Simulations of multiple mini-tip effects in STM images (that ignore electron interference effects) may be understood as modeling multiple mini-tip (or tip shape) effects in images that were recorded with other types of SPMs as long as the lateral sample feature sizes to be imaged are much larger than the effective scanning probe tip sizes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Scanning probe microscopy (SPM) images are often degraded due to the effects of two (or more) protrusions on the probe tip (i.e. effective mini-tips on a blunt tip), as well as containing sample tilt errors, image bow and drift, and stepping errors that occur while scanning the tip in two dimensions (2D) over the sample surface. Averaging methods have long been used to remove scanning errors. There are also well-established techniques for straightening out keystone-shaped images that result from sample tilt and image drift, and for the removal of image bow by z-flattening using least-squares higher-order polynomials to model this distortion [1–3]. Removing multiple-tip artifacts from SPM images has, however, only recently been accomplished through the adoption of crystallographic image processing (CIP) techniques [4–7], which one may consider as being a kind of a crystallographic averaging in reciprocal (Fourier) space of the intensity of symmetry-related features in direct space.

The transmission electron crystallography community developed CIP to enable the extraction of structure factor amplitudes and phase angles from (parallel illumination) high-resolution phase contrast images of crystalline materials within the weak phase object approximation [8, 9]. It has also been used for the correction of these images for the effects of the phase contrast transfer function, two-fold astigmatism, sample tilt away from low-indexed zone axes, and beam tilt away from the optical axis of the microscope. The central ideas of this kind of 2D crystallographic symmetry averaging have also been applied to scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) in order to increase the signal-to-noise ratio of Z-contrast imaging [10].

In the context of SPM, CIP addresses multiple scanning probe tip imaging artifacts effectively. This is an application that is beyond its original conception by the electron crystallography community and also does not apply to Z-contrast STEM imaging.

Since one may define 2D image-based crystallography independent of the source of the 2D patterns as being concerned with categorizing, specifying, and quantifying 2D long-range ordered patterns [4], CIP is also a good term for procedures as applied to SPM images of 2D periodic objects.

This process consists in its simplest form in the application of a Fourier transform to the 2D digitized image (called Fourier analysis), detection of the most likely plane symmetry in reciprocal space, enforcement of this symmetry by averaging of the symmetry related Fourier coefficients to remove all kinds of degradations, and finally inverse-Fourier image reconstruction (called Fourier synthesis into direct space). Irregularities in the 2D periodic array that is to be imaged, e.g. 2D periodic motif vacancies, are “averaged out” by CIP. For representative results, one should therefore aim for a ratio of regularly repeating features to irregularities of at least 50 (or better 100) to one.

By means of CIP, one can also extract the prevailing point spread functionFootnote 1 of the SPM [4] and use it for the correction of subsequently recorded images [7]. One may refer to this function loosely as the “effective scanning probe tip” as it represents the convolution of the effects of the actual tip shape with all kinds of scanning and signal processing irregularities.

The symmetrizing is done in reciprocal space because of its computational efficiency. Since the Fourier coefficients were symmetrized, the CIP processed images are also symmetrized to the chosen 2D space group. The 2D space groups are also known as plane symmetry groups and combine 2D translations symmetries with 2D point symmetries, see “Appendix A”. We use the international (Hermann–Mauguin) notations for plane symmetry and 2D point symmetry groups [11] throughout the paper. When compared to CIP, conventional Fourier filtering [12] of 2D periodic images leads to translation averaging only. This means that the latter technique does not take advantage of the site symmetries in the plane groups (so that pure translation averaging will be up to 12 times less effective than CIP).

Consider, for example, the image shown in Fig. 1a, whose p4-symmetry is “symmetrically perfect” because we imposed this symmetry on an experimental “nearly-p4” STM image [6, 13] using CIP. (Crystallographic notations such as p4 and basic 2D crystallography are briefly discussed in “Appendix A”.) Using Photoshop,Footnote 2 we have artificially constructed in Fig. 1b an image somewhat akin to what one would see with three SPM tips shifted laterally and vertically with respect to each other, simultaneously scanning the same surface, with signals beating against each other.

Modeling the effects of a triple-SPM-tip on the image of a p4 source. a A 550 by 550 pixel image whose p4-symmetry is known by design. (Based on its “experimental counterparts” in refs. [6, 13], the area of this image corresponds to approximately 340 nm2). b A “hypothetical image” to model what a triple-SPM-tip would produce when imaging this “sample,” constructed in Photoshop by overlaying two copies of the p4 image, shifting them, and setting the blend mode to Overlay (footnote 2), with the opacity reduced for each to model different heights for the three tips. (A small ~15 by 26 pixel wide margin of the unobscured image is seen in the upper–left-hand corner behind the overlain image). c Crystallographically averaged p4 plane symmetry reconstruction of a 512 by 512 pixel fully obscured portion of this “sample.”

We note that both the unobscured image, Fig. 1a, and the obscured one, Fig. 1b, possess the same translation symmetry, which is that of the square 2D Bravais lattice. It was noted in Ref. [14] that subsequently recorded images from the same 2D periodic array that possess variations in the motif but possess the same translation symmetry are the hallmarks of blunt scanning probe tips. While obscured images have typically been discarded in the past, CIP presents an alternative to recover information from them. Figure 1c shows the inverse-Fourier image reconstruction after p4 symmetry enforcement in reciprocal space (following the guidelines in “Appendix B”) of the fully obscured portion of Fig. 1b. One sees a quite faithful reproduction (apart from a decrease in contrast) of the one-tip image, Fig. 1a as the 2D point symmetry of the motif is restored to group 4.

In the case of images that were recorded with multiple mini-tips, the whole plane symmetry enforcing procedure can, by virtue of the Fourier shift theorem [15], be thought of as aligning the 2D periodic motifs of all independent SPM images from the multiple mini-tips on top of each other, thus enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio significantly when done correctly. Within this context, CIP can be understood as a “sharpening up” of the effective scanning probe tip.

The present work shows in detail why CIP works and builds upon prior work [4–7] that shows how it is done at a practical level. In order to show in detail why CIP works, we will modify a common approach for simplifying the details of the problem, the independent-orbital approximation (IOA) to allow for the beating of signals from multiple mini-tips in STM. That is, we explore how “scanning tunneling probe tip surface structures” add both linearly and quantum mechanically to the recorded signal in convolution with the features of the “sample surface structure”.

Although the underlying physics of the IOA approach is specific to STM imaging, simulations of multiple-tip effects that ignore electron interference effects may be understood as modeling multiple mini-tip (or tip shape) effects in images that are recorded with other types of SPMs (where quantum mechanical interference effects can be safely ignored). It is well known that the nominal probe size is in STM imaging typically of the same (atomic or molecular) order of magnitude as the sample surface features that are to be imaged. For CIP to be applicable to images of 2D periodic arrays that were recorded with other types of SPMs (footnote 1), the effective probe size has to be much smaller than the lateral size of the features to be imaged. Although this requirement is trivial for any kind of meaningful imaging with SPMs (other than STMs, atomic or molecular resolution atomic force microscopes, and critical dimension SPMsFootnote 3), it needs to be stated repeatedly as the literature abounds with conclusions that largely ignore it.

We first review the IOA, show how to modify it for two tips, and then trace back the resultant image to the salient details within its Fourier transform to show why CIP works. The changes wrought in the tunneling current by having two (or more) tips are outlined thereafter. The arrangements of multiple mini-tips in our analyses do not possess projected 3D point symmetries higher than 1, i.e. 360 degree rotations about arbitrary axes.

We begin with a treatment of double-tips since one may consider it a worst-case scenario of multiple tips, as will be illustrated later in the paper. We also examine the effect of double-tip height variations on the images and on the applicability of CIP.

In particular, we show that the 2D Fourier transform of the derived current resulting from two tips is comprised of the same Fourier coefficients as a single tip. The currents from the two tips differ in a phase term in reciprocal space [15] arising from the addition of complex numbers with different phases. These phase differences between two contributors may reduce the amplitudes (at a given reciprocal space point). CIP lessens this effect by averaging the Fourier coefficient amplitude and phase at such a point with amplitudes and phases at symmetry-related points.

We show the wide range of double-tip separations that are amenable to CIP. There are, however, certain double-tip separations for which some of these phases take prominent Fourier coefficients to zero, thereby obscuring the current map to the extent that even CIP cannot improve it.

Methods

The independent-orbital approximation

We first sketch Chen’s derivation [16] of an STM image for a surface structure having plane symmetry p4mm (and, thus, a square lattice) using the IOA, in which the total tunneling current is approximated by the sum of the tunneling currents from independent atomic states. (The difference between lattices and structures is clarified in “Appendix A”.) Since a square lattice/structure combines two identical perpendicular one-dimensional lattices/structures, we find the total tunneling conductance to be of the form:

where the conductance of the nth atom g(x − na, y − ma, z) is a function with periodicity a in both directions, yielding a discrete Fourier transform with identical primitive lattice vector lengths b = 2/a and Fourier coefficients,

Only the lowest five terms in the Fourier series contribute significantly to the STM image, due to the reflection symmetry of the conductance function g( r ), \({\tilde{G}_0} (z)\) and \(\tilde{G}_{ - 1,0} \left( z \right) = \tilde{G}_{1,0} \left( z \right) = \tilde{G}_{0, - 1} \left( z \right) = \tilde{G}_{0,1} \left( z \right) \equiv \tilde{G}_{1} \left( z \right)\). Then the total conductance function to this order is

The topographic SPM image, due to ∆z(x) corrugation altering a smooth surface and representing a structure, is related to the current image by, [16]

To calculate the required Fourier coefficients, Chen notes that the term with the highest power of r dominates the behavior of hydrogenic wavefunctions at low-energies (up to a few eV), so one can effectively approximate them with Slater orbitals [17, 18],

where, unlike hydrogen eigenstates, the principal quantum number is n ≥ 0. Here \(Y_{lm} \left( {\theta ,\varphi } \right)\) is the standard spherical harmonic function. These are convenient also because they may be calculated by taking derivatives with respect to the orbital exponent λ (proportional to the square root of the energy of the state) and to z of \(\psi_{000} \equiv C{{e^{ - \lambda r} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{e^{ - \lambda r} } r}} \right. \kern-0pt} r}\) (also recognized as the Yukawa potential).

The conductance distribution for an s sample state and an s tip state is \(e^{ - 2\kappa r}\) (see Chen’s Table 6.1 for other combinations, such as \(\cos^{2} \theta e^{ - 2\kappa r}\) if either the sample or the tip is a p z state and the other is an s state). Then taking the derivative of an integral identity [19] gives,

and the similarly derived,

where,

So the topographic image is given by,

for an s sample state and an s tip state, where,

If either the sample or the tip is a p z state and the other is an s state, the topographic image is given by,

and so on, with the corrugation (real-space lattice/structure) multiplied by a z-dependent amplitude.

Results

Two scanning probe tips

If one were imaging using an atomic state with two lobes aligned parallel to the x-axis, one could follow the procedure Chen outlines [20] in which for a quantum mechanical p x tip state, say, one takes “derivatives of the sample wave function at the nucleus of the apex atom of the tip” with respect to x to get the tunneling matrix elements. This results in the current images from each sample atom being doubled, as pictured in his 1987 paper [21].

In many cases, however, an STM tip having a pair of mini-tips—due to manufacturing error, damage to the tip, or the originally atomically sharp tip having picked up some material from the sample or the surrounding—is likely to have them separated by a much larger distance than the lobes of an atomic orbital. Indeed the separation distance will likely be of the same order as the inter-atomic or inter-molecular spacings of the sample.

In such a case, we can treat such a doubled tip as two well-spaced s tips (keeping our s sample), for example, and rely upon the reciprocity principle: [22] by “interchanging the tip state and the sample state, the conductance distribution [and hence the image is] unchanged”. We saw above that a p x tip state imaging a real-space structure would result in a current image having each sample atom (or molecule) doubled. One would get a similar looking current image using a single tip on a lattice/structure one has cloned, after shifting the second lattice/structure’s origin along the x-axis by the distance between the lobes of the p x tip. With a double-tip whose spacing is significantly larger, the same principle applies. We will see, however, that tip separations on a scale matching the sample lattice constant give the new possibility that the two currents will beat against each other.

As the pair of s tips (on a blunt scanning probe tip) is scanned over the surface, each tip would encounter the largest charge density in the x direction at different positions of the scanning head holding the two tips. If the tip separation w were precisely (an integer times) the periodicity of the real-space lattice/structure, the conduction signal would simply be twice as large and the topographic image would be unchanged except for brightness from what a single tip would yield. If, on the other hand, the tips were separated by any other distance, the two tips would register different tunneling charge densities at each position of the scanning head, and the pair of conduction signals would beat against each other, altering the topographic image registered.

For our single-tip on a cloned lattice/structure, we still have atoms that are independent of each other so that they do not shift position when new neighbors are slipped into the interstices by the duplication and shift process. This is a reasonable assumption if the spacing between atoms is (much) larger than the atomic extent.

The resulting topographic image would be given by,

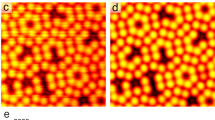

where we have shifted the cloned lattice/structure by u = w/2 in the positive x direction and the original lattice/structure by u in the negative x direction, as that simplifies the Fourier transform we will consider in a moment. The resultant topographic images at various tip separations are shown in Fig. 2 and we indeed do see increasing beating between the two signals as (b times) the tip separation approaches π/4 relative to the IOA p4mm surface wave functions having a period of 2π.

Topographic images due to various tip separations. Superpositions of the two IOA current sources with (b times) an STM tip half-separation a bu = 0, b bu = 0.6, c bu = 0.74, and d bu = 0.77 = π/4 − ε units in the horizontal direction, relative to the IOA p4mm surface wave functions having a period of 2π. A unit cell is inset in each case

To see where this loss of periodicity in the horizontal direction is coming from, we take the Fourier transform of (12),

This transform confirms that the reciprocal lattice spacing is independent of the number of tips. This property is a necessary condition for CIP to reconstruct a corrected image in real space. Reciprocal lattice vectors {H, K} are marked in Fig. 3a. “Appendix B” mentions a recently developed procedure to detect unambiguously the underlying 2D Bravais lattice of a 2D periodic surface structure [23] that aids the detection of multiple-tip artifacts in SPM images [24].

Fourier components at these tip separations. Fourier transforms of IOA p4mm wave functions with (b times) an STM tip half-separation a bu = 0, b bu = 0.6, c bu = 0.74, and d bu = 0.77 = π/4 − ε units in the horizontal direction, relative to the IOA p4mm surface wave functions having a period of 2π. Reciprocal lattice vectors {1,0} and {0,1} (= {H,K}) are marked in (a)

The transform (10) also reveals that suppression of Fourier components in the horizontal direction in reciprocal space by the phase terms Cos[n bu], seen in Fig. 3, is the cause of the significant change in the image registered by this model double STM tip in Fig. 2. In Fig. 3d, for π/4 − ε, this suppression becomes so severe that the character of the original image is entirely obscured for vanishing ε, see Fig. 2d.

Figure 4 shows the results of plane symmetry enforcements of the underlying p4mm symmetry for the superposition of IOA p4mm wave functions. This figure represents the final result of the CIP procedure on the images of Fig. 2. Even with significant suppression of spatial frequency information due to rather wide double-tip separations, CIP still is able to recover sufficiently reconstructed symmetrized “images” of the IOA p4mm wave functions, as seen for example in Fig. 4c, when compared with the single-tip image Fig. 2a.

Plane symmetry enforcement at these tip separations. Plane symmetry enforcement of the underlying p4mm symmetry for the superposition of IOA p4mm wave functions with (b times) an STM tip half-separation of Fig. 2. a bu = 0, b bu = 0.6, c bu = 0.74, and d bu = 0.77 = π/4 − ε units in the horizontal direction, relative to the IOA p4mm surface wave functions having a period of 2π

For bu = 0.77, Fig. 2d, we are beyond the limit at which one might confidently use CIP without a priori knowledge and/or an unambiguous determination of the underlying translation symmetry. With our prior knowledge of the underlying plane symmetry of the sample 2D periodic array, and/or with our recently developed geometric Akaike information criterion (AIC) for the unambiguous identification of 2D Bravais lattices [24] (see “Appendix B”), we can direct the popular CIP program CRISP [25] to produce a reconstruction, Fig. 4d, much more faithful to the IOA p4mm wave functions, Fig. 2 a than that contained in the two-tip image, Fig. 2d.

In the worst cases, e.g. for vanishing ε as extrapolated from Figs. 2d and 3d when even CIP cannot reliably reconstruct the correct images, they may be discarded.

Different heights for the two tips

We assumed a worst-case scenario in Eq. (12) in which the two tips were at precisely the same distance z above the surface structure. If one of the two tips is closer to the sample, its current will dominate the current from the higher tip, thereby exponentially reducing the obscuration of the image. In Sect. “Results”, above, we represented a double-tip by a single tip above a cloned lattice/structure, having shifted the clone one way along the x-axis and the original the other way by the same amount. In modeling two tips at different heights in such an approach, one could also raise the cloned lattice/structure higher than the original to yield the exponential dominance of the current from that original lattice/structure.

Tsukada, Kobayashi, and Ohnishi [26] found a reduction in interference with tip-elevation angle in their calculations using an antibonding H2 orbital model for a tip on graphite. By the time they reached a 0.26 rad elevation difference, the interference was much reduced.

Let us examine an STM tip separation that caused severe image artifacts, bu = 0.77 = π/4 − ε. We see from Fig. 5b that when one tip is at z = 1 Å from the surface and the second is raised to z = 1.2 Å, the obscurations in the image are much reduced. When the second is raised to z = 1.5 Å in Fig. 5c, the current dominated by the closer tip is not distinguishable from a single tip, Fig. 3a. This result is in agreement with the textbook statement that the exponential decay of the tunneling current with height over the sample ensures often sufficiently clear images even if there is more than one scanning probe tip.

The effect of uneven tip height on Topographic images. Superpositions of the two IOA current sources with (b times) an STM tip half-separation bu = 0.77 = π/4 − ε units in the horizontal direction, relative to the IOA p4mm surface wave functions having a period of 2π. In a both tips are at the same height. In b one tip is 20 % higher from the surface than the other, and c 50 % higher

Multiple tips

The final case to explore is the effect of multiple tips on image obscuration. Consider the two-tip separation that is the most problematic, with bu = 0.77 = π/4 − ε units in the horizontal direction, Fig. 3d. Suppose we add a second pair of tips separated by, say, one-third of that value, or bu = 0.26. We see in Fig. 6b that this addition does ameliorate the obscuration. (One gets a similar result if one makes the second pair of tips nonsymmetrical with respect to the origin, so that one is at bu = 0.26 and the second at bu = −0.15.) In Fig. 6c we add a third pair of tips at one-fifth of the separation of the first pair, with bu = 0.15. One sees that with six rather than two tips, the resultant image is hardly distinguishable from a single tip, Fig. 2a.

The effect of tip multiplicity on Topographic images. a Superpositions of the two IOA current sources with (b times) an STM tip half-separation bu = 0.77 = π/4 − ε units in the horizontal direction, with b a second pair of tips separated by one-third of that value, or bu = 0.26, and c a third pair of tips separated by one-fifth of the separation of the first pair, with bu = 0.15

Thus we see that the double-tip case is indeed some kind of a worst case. Additional tips provide nonzero contributions to the reciprocal space amplitudes at spatial frequencies that would otherwise be completely suppressed. This facilitates the application of CIP to bring out even more underlying information in the “sample”. So we expect that crystallographic averaging would work well in removing the effects of a blunt STM tip, consisting of multiple mini-tips.

Summary and conclusions

CIP may often be used to remove multiple-tip artifacts from SPM images. Alternatively, one can think of the application of CIP as being analog to the “sharpening up” of a blunt tip to enhance the signal-to-noise level.

We have modified the independent-orbital approximation (IOA) to account for the beating of signals from two tips. Tracing back the resultant image to the salient details within its Fourier transform shows why CIP is effective. The tunneling currents from the two tips differ in a phase term in reciprocal space that may reduce the Fourier amplitudes (and hence, the real-space modulation) at a given reciprocal space point. We show that CIP lessens this effect by averaging the amplitude and phase at such a point with amplitudes and phases at symmetry-related points.

We have also shown that the existence of more than two tips at random separations will tend to ameliorate pair-wise destructive beating of signals at a given reciprocal space point, providing additional amplitude at that Fourier point to restore some real-space modulation. Finally, we have recovered textbook knowledge that tip height variations will ameliorate image degradations because of the exponential falloff of the signal with the tip-surface distance.

In particular, we have shown that the 2D Fourier transform of the derived tunneling current resulting from two tips is comprised of the same Fourier coefficients as a single tip. We show the wide range of double-tip separations that are amenable to CIP. There are, however, certain double-tip separations for which some of these phases take prominent Fourier coefficients to zero, thereby obscuring the current map to the extent that even CIP cannot improve it.

Notes

Reference [7] demonstrates, for example, the application of CIP to two 2D periodic images (that were recorded from the same commercial calibration sample with the same atomic force microscope) under (i) standard and (ii) non-standard imaging conditions, i.e. an open feed back loop. That calibration sample was designed to possess plane symmetry p4mm and its lateral 2D periodic feature size were one order of magnitude larger than the nominal probe sizes. (The horizontal sample feature size was approximately a tenth of the nominal probe sizes.) The effective scanning probe tips were de-convoluted from these images and the one that corresponded to the standard imaging conditions was less than half of the size of its non-standard imaging conditions counterpart.

One duplicate of the p4 image was pasted on top of the p4 image and then shifted 3 pixels to the right and 15 pixels down, out of 550 pixels and a second duplicate was shifted up 9 pixels and right 26 pixels. The three layers were then combined using Photoshop’s overlay blend mode, the formulas for which are given at http://www.stackoverflow.com/questions/5825149/overlay-blend-mode-formula, with the opacity of the duplicate layers set at 70 and 30 %, respectively.

Critical dimension SPMs were developed specifically for the assessment of narrow and deep trenches as well as steep and high walls either as transients in the building-up of integrated circuits or in micro- and nano-electromechanical systems.

References

Yurov, V.Y., Klimov, A.N.: Scanning tunneling microscope calibration and reconstruction of real image: drift and slope elimination. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 65(5), 1551–1557 (1994)

Edwards, H., McGlothlin, R.: Vertical metrology using scanning-probe microscopes: imaging distortions and measurement repeatability. J. Appl. Phys. 83(8), 3952–3971 (1998)

Tsaftaris, S.A., Zujovic, J, Katsaggelos, A.K.: Automated line flattening of atomic force microscopy images. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Image Processing, 12–15 october 2008, pp. 2968–2971, San Diego, California (2008)

Moeck, P: Crystallographic image processing for scanning probe microscopy. In: Méndez-Vilas, A., Diaz, J. (eds.) Microscopy: Science Technology, Applications and Education, Formatex Microscopy Series, no 4, vol. 3, pp. 1951–1962 (2010). http://www.formatex.info/microscopy4/1951-1962.pdf

Moeck, P., Straton, J.C., Toader, M., Hietschold, M.: Crystallographic processing of scanning tunneling microscopy images of cobalt phthalocyanines on silver and graphite. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 1318, 149–154 (2011). doi:10.1557/opl.2011.278

Moeck, P., Straton, J.C., Hipps, K.W., Bilyeu, TT., Rabe, J-P., Mazur, U., Hietschold, M., Toader, M.: Crystallographic STM image processing of 2d periodic and highly symmetric molecule arrays. In: Proceedings 11th IEEE International Conference on Nanotechnology, pp. 891–896 (2011), doi: 10.1109/NANO.2011.6144508

Moon, B, Employment of Crystallographic Image Processing Techniques to Scanning Probe Microscopy Images of Two-Dimensional Periodic Objects, Master of Science Thesis (Portland State University, 2011); http://www.nanocrystallography.research.pdx.edu/media/thesis14acorr.pdf

Hovmöller, S.: In: Ragan, C.I., Cherry, R.J. (eds.) Techniques for the Analysis of Membrane Proteins, pp. 315–344. Chapman and Hall, London (1986)

Zou, X., Hovmöller, S., Oleynikov, P.: Electron Crystallography. Oxford University Press, Electron Microscopy and Electron Diffraction (2011)

Morgan, D.G., Ramasse, Q.M., Browning, N.D.: Application of two-dimensional crystallography and image processing to atomic resolution Z-contrast images. J. Electron Microsc. 58(3), 223–244 (2009)

Hahn., T (ed.) Brief Teaching Edition of Volume A, Space-group symmetry, International Tables for Crystallography, 5th revised edition, International Union of Crystallography (IUCr), Chester (2005)

Park, S., Nogami, J., Quate, C.F.: Effect of tip morphology on images obtained by scanning tunneling microscopy. Phys. Rev. B 36(5), 2863–2866 (1987)

Mazur, U., Leonetti, M., English, W., Hipps, K.W.: Spontaneous solution-phase redox deposition of a dense cobalt(ii) phthalocyanine monolayer on gold. J. Phys. Chem. B 108(44), 17003–17006 (2004)

Iski, E.V., Jewell, A.D., Tierney, H.L., Kyriakou, G., Sykes, C.H.: Organic thin film induced substrate restructuring: an STM study of the interaction of naphtho[2,3-a]pyrene Au(111) herringbone reconstruction. J. Vac. Sci. Techn. A. 29(4), 041510 (2011)

Tables of Integral Transforms, Volume 1, Based in part on notes left by Harry Bateman, and compiled by the staff of the Bateman Manuscript Project. Erdelyi, A (ed.) (McGraw-Hill, 1954), p. 117, Eq. 3.1.5

Chen, C.J.: Introduction to Scanning Tunneling Microscopy, pp. 149–63. Oxford University Press, New York, Oxford (1993) (Oxford Series in Optical and Imaging Science 4, Eds. Lapp, M, Nishizawa, J-I, Snavely, BB, Stark, H, Tam, AC, Wilson, T, ISBN 0-19-507150-6)

Ibid, pp. 122

Slater, J.C.: Atomic shielding constants. Phys. Rev. 36, 57–65 (1930); Zener, C.: Analytic atomic wave functions. Phys. Rev. 36, 51–56 (1930)

Goodman, FO.: Summation of the Morse pairwise potential in gas-surface interaction calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 65(4), 1561–1564 (1976). This may also be proved using Gradshteyn, I. S, Ryzhik, I. M., Table of Integrals, Series, and Products 5ed (Academic Press, New York, 1980), p. 382 No. 3.462.3, p. 1095, No. 9.253, p. 1057, No. 8.950.3, and p. 385, No. 3.471.12

Chen, C.J.: Unified perturbation theory for STM and SFM. In: Wiesendanger, R., Güntherodt, H.J. (eds.) Scanning Tunneling Microscopy III, 2nd edn, pp. 161–162. Springer, Berlin (1996)

Chen, C.J.: Theory of scanning tunneling spectroscopy. J. Vac. Sci. Technol A 6(2), 319–322 (1988)

Supra note 16, p. 154

Bilyeu, TT.: Crystallographic image processing with unambiguous 2D Bravais lattice identification on the basis of a geometric Akaike information criterion, Master of Science Thesis (Portland State University, May 2013). http://www.nanocrystallography.research.pdx.edu/media/cms_page_media/6/Taylor_thesis_final.pdf

Straton, J.C., Bilyeu, T.T., Moon, B., Moeck, P.: Double-tip effects on Scanning Tunneling Microscopy imaging of 2D periodic objects: unambiguous detection and limits of their removal by crystallographic averaging in the spatial frequency domain, special issue “Advances in Structural and Chemical Imaging”. Cryst. Res. Technol. 49, 663–680 (2014). doi:10.1002/crat.201300240

Hovmöller, S.: CRISP: crystallographic image processing on a personal computer. Ultramicroscopy 41(1), 121–135 (1992). (This Windows™ based software is the quasi-standard for electron crystallography of inorganics in the weak phase object approximation. Just as “2dx”, its quasi-standard counterpart for electron crystallography of 2D membrane protein crystals (Gipson, B, Zeng, X, Zhang, ZY, Stahlberg, H: 2dx—user-friendly image processing for 2D crystals. J. Struct. Biol. 157(1), 64–72 (2007)), this program is based on ideas of Nobel Laureate Sir Aaron Klug and coworkers that resulted in the creation of the MRC image processing software suite over more than a quarter of a century (e.g. Crowther, R.A., Henderson, R., Smith, JM.: MRC image processing programs. J. Struct. Biol. 116(1), 9–16 (1996))

Tsukada, M., Kobayashi, K., Ohnishi, S.: First-principles theory of the scanning tunneling microscopy simulation. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 8(1), 160–165 (1990)

Aroyo, MI.: Book Review Foundations of Crystallography: with Computer Applications by M. M. Julian, Acta Cryst. A 65, 543–545 (2009)

Julian, MM.: Foundations of Crystallography: with Computer Applications, CRC Press (2008)

Hahn, Th (ed.) International Tables for Crystallography, volume A, Space group symmetry, 5th Edition, International Union of Crystallography (IUCr), Chester (2005)

Förster, S., Meinel, K., Hammer, R., Trautmann, M., Widdra, W.: Quasicrystalline structure formation in a classical crystalline thin-film system. Nature 502, 215–218 (2013). doi:10.1038/nature12514

Wasio, N.A., Quardokus, R.C., Forrest, R.P., Lent, C.S., Corcelli, S.A., Christie, J.A., Henderson, K.W., Kandel, S.A.: Self-assembly of hydrogen-bonded two-dimensional quasicrystals. Nature 507, 86–89 (2014). doi:10.1038/nature12993

Kanatani, K.: Geometric information criterion for model selection. Int. J. Computer Vision 26(3), 171–189 (1998)

Triono, I., Otha, N., Kanatani, K.: Automatic recognition of regular figures by geometric AIC. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. E81–D(2), 224–226 (1998)

Authors’ contributions

JS crafted the mathematical structure of the paper, generated the “hypothetical images” that model the obscurations CIP is capable of removing, performed some of the image processing, and drafted the whole paper. BM performed some of the image processing and helped edit the paper. TB contributed to the development of our method for the unambiguous detection of the underlying Bravais lattice of a 2D periodic SPM image, provided Fig. A1, and helped edit the paper. PM helped write and edit the paper, drafted the appendices, performed some of the image processing, and provided overall guidance to the whole project since applying CIP to SPM images was his basic idea (for which he also secured a patent for his employer). BM and TB each prepared Master of Science theses on the application of CIP to SPM images of 2D periodic arrays. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by awards from Portland State University’s Venture Development Fund and the Faculty Enhancement program. A grant from Portland State University’s Internationalization Council is also acknowledged. JS would like to thank C. Julian Chen for helpful comments on charge density distributions.

Competing interests

PM secured for Portland State University a patent for applying CIP to SPM images. He is also a Deputy Editor-in-Chief of Advanced Structural and Chemical Imaging.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

40679_2015_14_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Plane symmetry groups and their type I inclusion relations. The hierarchy of the 17 plane symmetry groups and their type I inclusion relations. A group lower on the diagram is a subgroup of (included in) a group to which it is connected higher on the diagram. Color (grayscale) indicates the Bravais lattice type, and the multiplicity of the general position per lattice point is indicated by height in the diagram. (The graph is of the contracted type, where some of the nodes refer to conjugate subgroups [27]).

Appendices

Appendix A: Brief introduction to 2D space and point symmetries

A lattice is the array of all points (lattice points) in a pattern with identical surroundings. That is to say, a pattern will look the same from one lattice point as it does from any other lattice point (if the pattern extends to infinity). The lattice is therefore not a physical entity, but an abstract mathematical construct that is useful for dealing with translation symmetry. In a two-dimensional (2D) periodic pattern, translation symmetry is conveniently represented by a lattice vector t(s 1, s 2) = s 1 a 1 + s 2 a 2 with components of two linearly independent unit translation vectors a 1 and a 2 (basis vectors of the primitive unit cell of the lattice) and s 1 and s 2 integers. That is to say, shifting a 2D periodic pattern along any lattice vector that possess these unit vectors as (integer) components leaves the pattern invariant when translation symmetry is present. Mathematically exact 2D translation symmetry (and the 2D crystallography that builds on it) requires patterns that are infinite in extent and perfect, but the concepts are also useful as approximations for periodic patterns of finite size and patterns where a few individual array members are missing or misplaced, i.e. typical SPM images. A lattice can, therefore, be assigned to finite periodic structures that consist of atoms or molecules.

Only five types of lattices are compatible with the 10 crystallographic point symmetry types in 2D. The former are known as the 2D Bravais lattices, typically referred to as oblique, rectangular primitive (rectangular), rectangular centered (centered), square, and hexagonal lattices. A 2D crystallographic point group is a group of symmetry operations (e.g. a combination of the identity, rotations, and reflections) that leaves at least one point of a plane object invariant, and contains only those rotations that are considered crystallographic rotation operations because of their compatibility with the five 2D Bravais lattices. There are only 10 such symmetry groups (1, 2, m, 2mm, 4, 4mm, 3, 3m, 6, and 6mm) in 2D.

The leading number in the point group symbol denotes the highest-order rotational symmetry operation about a point in the plane. The one or two m’s in the symbol denote the presence of one or more mirror (reflection) symmetry operations. The normals of these mirror lines are within the plane of the figure. The 2D crystallographic point groups possess subgroup-supergroup relations (inclusion relations), where a supergroup contains all of the symmetry operations of a corresponding subgroup, plus some additional symmetry operation(s). (In mathematical terms, one often speaks of non-disjoint entities and inclusion relations when there are subgroups-supergroup relations in a general sense.)

By combinations of the five translation symmetry types (Bravais lattices) with the ten crystallographic point symmetry types, a finite set of 2D space symmetry types is obtained. Each of the 17 plane symmetry groups in this set tiles 2D space in a long-range ordered manner with no gaps. Any 2D periodic pattern that tiles 2D space must have the symmetry of one of these 17 groups. The leading letters p (for primitive) and c (for centered) in all plane symmetry group symbols, i.e. p1, p2, pm, pg, cm, p2mm, p2mg, p2gg, c2mm, p4, p4mm, p4gm, p3, p3mL, p31m, p6, and p6mm refer to the lattice type. There are, thus, 15 plane symmetries group on the basis of primitive lattices and two on the basis of centered lattices.

The 2D crystallographic space groups possess subgroup-supergroup relations as well. A distinction is made between so called translationengleiche (type I) and klassengleiche (type II) subgroup-supergroup relations. In this paper, we are only concerned with the maximal and minimal type I subgroup-supergroup relations, which are based on unit cells of the same size (area). Maximal and minimal mean in this context that there is no other group between a subgroup and its supergroup and vice versa. The hierarchy of the 17 plane symmetry groups, along with their (maximal and minimal type I) inclusion relations and Bravais lattices is illustrated in Additional file 1: Figure S1.

The nomenclature of the plane symmetry groups might seem dauntingly complex to the novice, while it relies in fact on only a few rules. In this paper, we use the Hermann–Mauguin symbols [11] as they provide deeper insight into the orientation and mutual arrangement of symmetry operations.

As mentioned above, the leading letters in the symbols of plane symmetry groups refers to the type of lattice: p for primitive (i.e. containing one lattice point) and c for centered (i.e. containing two lattice points). If the p or c is followed by a number, it refers to the highest rotation symmetry about a point in the plane. When one views a 2D plane symmetry group as an orthogonal projection of a 3D space group, these rotation points are projections of rotation axes that are oriented perpendicular to the plane.

If the second entry in the plane symmetry group symbol is an m or g and there is no third and fourth symbol, these letters refer to a mirror or glide line perpendicular to one of the coordinate axes. This is typically the x-axis (parallel to unit translation a 1 ), but there can be different settings. The full Hermann–Mauguin symbols for these three plane symmetry groups are: p1m1, p1g1, and c1m1, whereby the first and last numbers signify that there are only identity (360º) rotations about the projected z-axis and the y-axis (parallel to unit translation a 2 ), respectively. The underlying projected z (1st), x (2nd), and y (3rd) axis sequence is typical for plane symmetry group names that are based on the two rectangular Bravais lattices. As there are no perpendicular x and y axes in the oblique Bravais lattice, the short Hermann–Mauguin symbol of p1 and p2 is indistinguishable from the full (four-entry) symbol.

For the square and hexagonal Bravais lattices, the first symbol after the leading p designation for the lattice type in a plane symmetry group symbol refers to the projected z-axis direction. For both 2D lattice types, the 3rd and 4th symbols in a full (and short) Hermann–Mauguin plane symmetry group symbol refer to symmetries along the x-axis and the \(\left\langle {1\bar{1}} \right\rangle\) directions. While rotation axes are oriented parallel to these directions, mirror and glide lines are represented by their normals, which are oriented perpendicular to these directions.

Plane symmetry groups that contain a c or g in their symbol are either centered or non-symmorphic. This results in the necessity of certain Fourier coefficients being zero. This is analogous to 3D X-ray crystallography, where centered and non-symmorphic space groups result in “systematically absent” or in other words “extinct” reflections.

The Bravais lattices possess the holohedral (highest) plane symmetries, i.e. p2, p2mm, c2mm, p4mm, p6mm, within each type I subgroup-supergroup tree. Point symmetries within a plane symmetry are referred to as site symmetries. The point positions with the lowest Wyckoff letter and multiplicity possess point symmetries 2, 2, 4, and 6mm in the four primitive Bravais lattices. These are the positions of the (one) lattice point that defines the primitive unit cell of the 2D periodic pattern over the application of the unit translations. In the unit cell of the rectangular centered Bravais lattice, there are two lattice points and both possess point symmetry 2mm. This lattice possesses a primitive sub-lattice, which contains only one lattice point (just as all of the primitive Bravais lattices do). The size of the unit cell of the primitive sub-lattice is one half of the size of the rectangular centered cell. This sub-unit cell is characterized by unit translations of equal magnitude that can be oriented with respect to each other at any angle other than 60º, 90º, or 120º.

The primitive unit cells possess the shapes of a parallelogram, a rectangle, a square, and a hexagon. The primitive sub-unit of the rectangular centered unit cell possesses the shape of a rhombus. The convention for the Bravais lattice unit cells is that the x-axis is taken downwards from the upper left vertex with direct space coordinates (0,0) and the y-axis is taken to the right, leading to the coordinates (1,0) for the lower left vertex and (0,1) for the upper right vertex. Ref. [28] provides a concise and elementary introduction to crystallography in general, and covers all of the material above in considerably more detail. In addition, there is a plethora of other introductory texts and information online readily available if the reader desires a better understanding of 2D crystallography. Ref. [29] is the definitive crystallographic standard and covers the direct space aspects of all 17 plane (and 230 space) symmetry groups comprehensively. Ref. [11] is the “brief teaching edition” that complements Ref. [29].

Quasicrystallinity in 2D, i.e. non-periodic long-range order coupled with non-crystallographic point symmetries has been observed recently [30, 31], but is beyond the scope of CIP as described in this paper.

Appendix B: Decisions as to which plane group to enforce

In order to determine the plane symmetry to which an image most likely belongs, the traditional approach is to use Fourier coefficient (FC) amplitude (RA % or Ares) and phase angle (φ Res or φ res) residuals [4, 8, 9, 23, 24]. These kinds of residuals are used as figures of merit for determining which plane symmetry group best models the image (or the sample surface structure having been imaged). As a general heuristic, smaller residuals indicate a closer match between the experimental image and an ideal plane symmetry model. Amplitudes are generally less reliable than phases so that a small FC phase angle residual has traditionally been more useful for identifying plane symmetries.

In addition, one traditionally utilizes the so called A o/A e ratio [4, 8, 9] for those six plane symmetry groups that possess systematic absences [11]. This ratio is defined as the amplitude sum of the Fourier coefficients that are forbidden by the plane symmetry but were nevertheless observed (A o) divided by the amplitude sum of all other observed Fourier coefficients that are allowed (A e) by the plane symmetry. For the six plane groups to which this ratio is applicable, a large ratio makes it more unlikely that the respective group is the right plane symmetry group.

There is, however, currently no fully objective way to use these traditional residuals to assign the correct plane symmetry group. The reason for this is type I subgroup and supergroup relations [11] between many of the 16 higher symmetric plane symmetry groups [23]. Whenever the FC phase and amplitude residuals of an image are not significantly larger for a higher symmetric plane symmetry group than for its respective type I subgroups, and the A o/A e ratio is not too high, one would generally conclude that this particular group is the more likely plane group, in comparison to other groups in its subgroup/supergroup tree. As implicitly mentioned above, there is currently no objective criterion on what “not significantly larger and not too high” may mean in numerical terms.

Given the subjectivity inherent in the use of the three traditional plane symmetry deviation quantifiers, there has been a need for a statistics-rooted measure that quantifies deviations from 2D translation symmetries (in reciprocal and direct space). Such a measure has been recently developed and allows the 2D Bravais lattice to be unambiguously identified because it is based on a geometric Akaike information criterion (AIC). Geometric AICs have been successfully used in a wide range of classification schemes involving non-disjoint models [32, 33].

In brief, the new assessment method involves the position of the (1,0), (0,1) and (1,1) FC peaks in a 2D Fourier transform amplitude map relative to the (0,0) FC peak of an experimental or simulated image. These positions are directly related to the reciprocal and direct lattice parameters of a 2D periodic image, and thereby to the shape of the 2D primitive unit cell (or sub-unit cell in case of the rectangular centered 2D Bravais lattice in direct space).

Residuals J are defined as the sums of squared distances from the vertices of the reciprocal space unit cell of a 2D periodic image to the corresponding vertices of the quadrilaterals that represent the shapes of the unit cells of the 2D Bravais lattices (in reciprocal space). As the conversion to direct space is straightforward, one can obtain from these kinds of residuals as well how much the shape of the direct space unit cell of 2D periodic data differs from the shapes of the quadrilaterals that represent the unit cell of the four primitive 2D Bravais lattices and the unit sub-unit cell of the rectangular centered lattice.

Assuming that deviations from the translation symmetry in the 2D periodic image are only due to random errors with a Gaussian distribution of mean zero, a geometric AIC is applicable as described in refs. [23, 24]. This allows for unambiguous identifications of the prevalent translation symmetry (2D Bravais lattice) and restricts the plane symmetry group an image may possess to those that are compatible with this particular translation symmetry.

For example, we obtain for both bu = 0.6, Fig. 2b, and bu = 0.74, Fig. 2c, a square unit cell as underlying translation symmetry from the application of our geometric AIC procedure. This is as expected, because we showed in the main text of this paper that the underlying translation symmetry cannot be affected by double-tips (and, thus, cannot vary with their separation). Our new procedure is, thus, optimal for detecting blunt tip artifacts in SPM images.

Our identification of square lattices justifies the enforcement of plane symmetry group p4mm on the basis of the three traditional figures of merit for plane symmetry group determinations for both bu = 0.6 and 0.74 (Figs. 2b, c, resulting in the plane symmetry enforced reconstructions of Figs. 4b, c). Note that there are only two other plane symmetry groups, i.e. p4 and p4gm, that are compatible with a square lattice, see Fig. A1. (While p4 is a maximal type I subgroup of p4mm, the plane symmetry groups p4gm and p4mm are disjoint.)

For \(bu \, = \, 0.77 \, = \, \frac{\pi }{4} - \varepsilon\), Fig. 2d, we obtain again a square unit cell from the application of our geometric AIC procedure, while CRISP [25] determines a rectangular unit cell and suggests p2 mg as most likely plane symmetry group. Note that even the extreme banding as seen in Fig. 2d can be corrected by CIP because we were able to identify the correct translation symmetry with the help of our geometric AIC procedure (and had prior knowledge on this anyway). Indeed, the enforcement of p4mm symmetry does give a recognizable reconstruction of the sample image in Fig. 4d, although the motif of the unit cell is now somewhat “squarish” rather than “rounded”.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Straton, J.C., Moon, B., Bilyeu, T.T. et al. Removal of multiple-tip artifacts from scanning tunneling microscope images by crystallographic averaging. Adv Struct Chem Imag 1, 14 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40679-015-0014-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40679-015-0014-6