Abstract

Mechanotaxis is the directed migration of a cell due to forces it senses from the substrate, which are caused mainly by the presence of other cells or by external traction forces. The resulting cell movement plays important biological roles for example in wound healing, the functions of the immune system, organogenesis and metastatic diseases. We present a model to simulate collective cell migration based on the forces that cells exert on elastic substrata. It characterizes the influence of cell and substrate stiffness on the collective migration of cells. The simulations initially represent a two-dimensional (monolayer) problem, and are then extended to represent migration in a three-dimensional extracellular matrix. The model is generic and can be utilized to study a variety of biological processes where migration occurs including tissue repair, cancer and infiltration of white blood cells to an infection site.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The ability to move is an essential feature of living cells, without which many biological processes could not occur, including organ development and growth, wound healing and the normal immune response to infection. In the context of disease, understanding the migration behavior of cells is particularly important in the cascade leading to the formation of cancer metastases. Some of the key mechanisms that stimulate cell migration are chemotaxis (movement along a gradient of a soluble chemoattractant), haptotaxis (directional movement along a gradient of ECM-bound chemoattractants) and mechanotaxis [cell mobility triggered by mechanical cues such as substrate stiffness gradients (durotaxis), or migration towards a mechanically strained area (tensotaxis)].

Tensotaxis occurs when a cell responds to signals resulting from mechanical strains induced in its substrate or changes in the substrate stiffness [1]. To understand cell migration as an outcome of mechanotaxis, and in particular regarding the behavior of multiple cells in cultures, a theory is needed to assess the influence of the cellular forces applied on the (extracellular) environment, the effects of cell proliferation and death, the interactions between the cells, as well as the elastic properties of the substrate. A mathematical framework can then serve to design experiments and extract additional information from experimental work [2, 3]. A model makes it possible to isolate controlling parameters and factors in the experiments, and a simulation enables the testing of the individual contributions of the parameters and sensitivity to changes in their values upon migration.

The aim of this study is to describe a novel cell migration model based on physical and analytical theories characterizing the connections and influences between a cell and its surroundings (neighboring cells and the extracellular environment). One of the goals is to produce a 3D model that lends itself to simulating the migration process of diverse cells and situations, thus providing better insights into cell communication, specifically as regards mechanotaxis.

Mechanotaxis

Cell movement occurs when the cell applies forces to the substrate (in two dimensions, 2D) or to the extracellular matrix or medium (in three dimensions, 3D). These localized forces can be sensed by neighboring cells [4–7] which, in turn, migrate in the general direction of these signals.

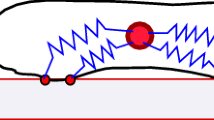

Individual cell movement has been likened to worm-like crawling (Fig. 1) [1, 5, 8–10]. Cells “pinch” the substrate at adhesion points and exert forces that deform the surrounding substrate. Cells also sense changes in the substrate’s mechanics, i.e., stress or stiffness, through the same cell-substrate physical connection sites. This mechanically connected network can transmit strains between closely situated cells, since the deformations decay far enough away from the cells [4, 7].

This type of communication can also cause a group of cells to move and migrate in a specific direction, for example to repair a wound as a result of wound-site contraction. The magnitude and transfer distance of the mechanical signal that takes place as cells deform their surroundings depend on the elastic modulus of the substrate. Several studies have shown that cells will migrate towards a stiffer substrate when situated on a soft one, and will tend to move upwards on a stiffness gradient. Winer et al. showed that cell stiffness can change as a function of the substrate stiffness [11]. The intensity of the mechanical signal defines the cell’s velocity and the overall rate of motion of the colony.

Effect of stiffness of the extracellular matrix

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a non-cellular structural component that exists between and around the cells, in all tissues and organs, and contains many fibrous proteins and polysaccharides [12]. The composition of ECM is unique to each tissue and produces a different range of elastic moduli, which define the density and spatial organization of the protein molecules. These long-chained molecules provide the ECM with its elasticity and stiffness. The structure and mechanics of the ECM play a major role in cell migration, as many cells receive biochemical and biomechanical cues through it. It thus acts as a medium for cell-to-cell communication.

Ng [13], Dufort [7], and Lu [14] among others found that cells, especially cancerous ones, show a preference for a stiffer ECM. Generally, cells will tend to migrate towards a stiffer ECM zone, a feature that is associated with wounds and tumors that are much stiffer than normal tissue. Studies have reported ECM elasticity changes as a function of the type of cells inhabiting the substrate. The elasticity of the cell can be changed depending on the substrate type [8, 15–18] which is exploited in experiments on the subject.

The cell life cycle

Another important factor in the migration process takes place as part of the cell life cycle. During proliferation or death (necrosis, anokis or apoptosis), the cells interact differently with the substrate. There are indications of mechanical interactions of cells with the ECM during proliferation or after cell death such as regulation of processes [19] or pattern forming [20]. The mechanotaxic behavior of cancer cells is unusual in that there is a higher proliferation to cell-death rate and a different elastic modulus. However, substrate stiffness and dimensionality can have opposite effects on cell spread and viability. These relations and effects can be explored with migration models and simulations.

Cell migration models

The present study considers cells that are migrating through a space as discrete objects, rather than considering cell densities treated by continuum-scale models using partial differential equations. The approach where cells are treated as discrete objects falls within the class of cell-based models. Cellular-based modeling approaches can be classified into two important sub-classes: cellular-automata models, where the cell shape and position is represented by ‘occupying’ or ‘not occupying’ certain control areas (or volumes) that are dictated by a discrete lattice. In this sub-class, one can find the cellular-Potts models by Glazier and Graner [21], Merks and Koolwijk [32] and van Oers et al. [33]. The work of Borau et al. [31] represents a 3D voxel FE model for a single cell in a probabilistic setting, where also the interaction between the migration and deformation of the cell and the deformation of the cell nucleus were also taken into account. In the second sub-class, which will be considered in this study, cells are allowed to move continuously over a specified domain where the stiffness varies over the domain. This continuous cellular approach was developed in earlier studies by Byrne and Drasdo [34], Groh and Louis [35] and in Neilson et al. [36]. A review on particle methods applied to tumor growth and wound healing is given in Vermolen [37]. Various cell migration models with cell–cell contacts have been developed and focus mainly on group migration and single cell movement rather than interactions between (proximal or distant) neighboring cells. Today’s more powerful computers make it possible to run more simulations that control migration thorough various interactions, although most are based on 2D models [21–23]. Here by contrast, we model mechanical signals transmitted through the substrate to which the cell adheres that affect its rate of migration, orientation and directionality.

Several analytical models for cell mechanotaxis have been developed. Geris et al. [24] described a finite element model based on cell-to-cell spring-like interactions, with a drag force caused by the medium viscosity. Reinhart-King et al. [25] produced a video analysis of cell migration, and suggested a mean displacement coefficient as a function of time, speed and direction of persistence. In a model developed by Vermolen and Gefen [4], the cells influence one another by mechano-sensing traction forces arising from cell movement. During motion, a cell exerts a pulling force on the substrate, making a small deformation that a neighboring cell can sense and respond to by moving accordingly. Our model extends Vermolen and Gefen’s 2D cell migration model to a 3D spatial simulation. In the present approach, the deformation of the cell is not taken into account and all cells are assumed to be spherical in the 3D simulations. It is important to note that cell morphology and stiffness changes are required during migration, and especially in 3D migration through narrow passages, as will occur e.g. during cancer cell invasion, see Dvir et al. [30]. The likelihood of cells crossing the passage will be affected by the cell nucleus deformability. This aspect of motion will require more detailed definition of the cell structure and dynamics and is outside the scope of the current manuscript. In Borau et al. [31], a modeling study has been developed for a single cell migrating and deforming in 3D, and their modeling incorporated the interaction with the deformation of the cell nucleus indeed. One can foresee that their approach can be integrated with ours to extend the modeling to simulate en mass migration (of cell populations) in 3D. The next section outlines the physical model. “Results and discussion” presents the simulation results for illustrative cases of cell clustering and cancer metastasis.

Methods

The physical model presented here is composed of an analytical model and an algorithm developed to perform the cell mechanotaxis simulations in 2D and 3D under conditions where the number and types of cells, the complex substrate and other factors vary. The analytical model is based on the Potts model which assumes that each cell interacts with its neighboring cells and the substrate. To mimic physical ground truth, the model parameters are based on experimental results, and on stochastic movement.

The analytical model

Consider a mechanotaxis situation between two cells; i.e., a mechanical signal between the cells caused by the movement of one of the cells, which exerts a traction force on the substrate and causes the second cell to move towards it.

To simplify the model and calculations, the cells are treated as circles or spheres with radius R. In addition, since the deformations caused by cell movement are small compared to the substrate thickness, the deformations are assumed to behave like a spring.

The scalar strain energy density M was used rather than the traction force F, as it is easier to measure and to sum. The strain energy density exerted by a single cell on the substrate M 0 i , assuming small deformations and linear elasticity, can be calculated as

where \(E_{s} (\varvec{r})\) is the local elastic modulus of the substrate, and \(\varepsilon\) is the substrate strain beneath the cell center. The strain \(\varepsilon\) can be calculated as the displacement of the substrate, d, over the substrate width, L, given the pulling force exerted by the cell (Fig. 2a),

or by using Hook’s law:

Substituting \(\varepsilon\) into the cell strain energy density results in

where F i is the force exerted by the ith cell. We are only interested in forces exerted if a cell is viable and well adhered to the ECM, and can thus contribute to the mechanotaxis process.

We ignore interactions with the ECM after death or while proliferating, due to the very short simulation time interval and length of these processes.

Cell i affects its surroundings by pulling the substrate in its vicinity (Fig. 2). As a result, the strain energy density from the center of the cell is written as [4]:

\(r_{i}\) is the location of cell i, \(\lambda_{i} = \frac{{E_{s} (r_{i} )}}{{E_{c}^{i} }}\) is a measure of attenuation of the signal, due to the cell’s own elastic modulus, \(E_{c}^{i}\) and the local elastic modulus E s of the substrate. This result is true for every point in the medium, suggesting that all the cells have a mechanical way to communicate throughout the substrate. Merkel et al. [18] demonstrated this exponential decay experimentally, as a function of the thickness of the substrate. Summing all the strain energy density around the ith cell yields the total strain energy density of cell i:

From Eq. 7 we can calculate the size of the force a cell can sense. To calculate the migration direction of the cell, we sum the strain energies from the neighboring cells along the line connecting the centers of the cell and its neighbor:

Therefore the time-dependent displacement of the cell can be calculated as:

introducing the cell velocity v i , where \(\hat{z}_{i}\) is the unit vector of zi.

The dimension parameter, \(\alpha_{i}\), is defined by the cell viability and interaction with the ECM as: \(\alpha_{i} = \left( {\frac{{F_{i} }}{{\hat{F}}}} \right)^{2} \beta_{i} \frac{{R_{i}^{3} }}{f}\); f is the friction force and equals \(\mu F_{i}\). Thus \(\alpha_{i} = \beta_{i} \frac{{R_{i}^{3} }}{{\mu \hat{F}}}\), or 0 if the cell is not viable (cells do not move after death or negligibly while proliferating). We also define the mobility of the cell, \(\beta\); i.e., its ability to move as a function of its own elastic modulus and the substrate’s elastic modulus.

Studies have shown [26, 27] that cell velocity exhibits a non-linear dependency on the elastic modulus of the substrate, as shown in Fig. 3. We approximate the cell velocity to a Gamma distribution function of the form:

By letting all other parameters but \(\beta\) be independent of the substrate elasticity, \(\beta\) can be modeled as the function \(\beta (\lambda ) = A\lambda^{2} e^{ - B\lambda }\), A and B are dimension parameters, and can be found by using experimental values of \(\beta\) and \(\lambda\).

Cell speed as a function of the gel stiffness (dashed), and cell traction or elasticity (dotted) as a function of the gel stiffness [26]. The simulated cells mimic this type of behavior

Combining all of the above, the velocity of a single cell can be written as

Figure 4 shows \(\varvec{v}_{\varvec{i}} ({\text{E}}_{\text{s}} )\) Gamma-function behavior for different \({\text{E}}_{\text{c}}\) values, and suggests that cells with higher elasticity can move more easily and with greater speed. Figure 4 has been plotted for the 2D and for the 3D cases, where in the 3D case, the cell may have to cross through narrow passages, where the stiffness of the cell nucleus certainly has an impact on the deformability of the cell. The reduction in cell migration velocity as a result of cell deformability can be incorporated by adjusting the cell-friction parameter \(\mu\) to a larger value.

Velocity of a single cell as a function of substrate stiffness (E s ), in different cell elastic modulus E c values. The velocity behavior is comparable to a gamma function, as illustrated in Fig. 3

Cell migration is semi-random and not only determined by the environment. Randomness is thus introduced by defining two components of cell velocity: movement resulting from the cell surroundings; i.e. mechanotaxis, and a velocity vector randomized under the assumption that a cell would continue to migrate approximately at the same velocity with minor changes, which can be modeled by a normal distribution. We define a probability P mp that in a certain time-frame (TF) the cell velocity will derive from either mechanotaxis or from this random walk.

A signal detection threshold must be set or the unrealistic situation of two very distant cells interacting will occur. Based on Eq. (6), a minimal detectable signal (MDS) can be defined where the mechanical communication occurs. Introducing \(\varepsilon\) as the MDS yields

and setting the maximum distance between two cells to \(d = 30\;\mu {\text{m}}\) [24] will give us a value for \(\varepsilon\). Setting this value of \(\varepsilon\) as the MDS for all cells provides the maximum distance of the MDS—\(d(E_{s} ,E_{c} )\):

Reinhart-King et al. [24] approximated \(d = 10\sqrt {\frac{F}{{E_{s} }}}\) by analyzing two cell movements as a function of the force and elastic modulus of the substrate. Figure 5 compares Reinhart-King’s MDS distance with our model’s MDS distance. The main difference is the dependency of the MDS distance on the cell’s elastic modulus E c (via \(\lambda_{i}\)). Changing the cell type (i.e. its elastic modulus) can be used to calibrate the model.

Maximum distance for MDS as a function of Es. Dashed-dotted graph shows Reinhart-King’s distance [24]

We also define collision interactions between two cells, where cells are not allowed to overlap when impinging. The effect of the contact force resulting from a two cell collision is incorporated within the cell’s strain energy density. We define an allowed indentation between two cells due to collision, h, using contact mechanics [4, 28, 29] which gives us the strain energy density transferred in the collision:

M ij is subtracted from M(r i ) to calculate the cell’s final velocity. A subtraction of energy from z is therefore also required:

\(\hat{r}\) is a unit vector connecting the centers of the two cells.

The final problem to address is the mechanical communication of cells situated in regions of different stiffness (E s ). Our solution is to expand the use of Hook’s law. As above, two cells are connected through a spring; however, in this case the spring changes its constant, k, at the boundary of the ECM region (Fig. 2). An effective spring constant can be applied through the relation:

The relation between the elastic modulus E s and k is \(k = \frac{{E_{s} A}}{{L_{0} }}\), where A is the spring’s area (i.e. the cell contact area) and L 0 is the length of the spring. Combining this with an effective elastic modulus, and assuming A is the same for both cells we get:

where L 1 and L 2 are the distance of a cell from the boundary of the elastic modulus on the line connecting the two cell centers; hence

Simulation algorithm

To test this model, a simulation was conducted under certain assumptions to simplify calculations, running time and visualization. First we defined the simulation parameters, such as cell radius, number and locations, elastic modulus, traction force quantity and probability of the cells to proliferate or die (see Table 1). The total strain energy density was calculated for each cell in every TF, thus yielding the cell velocities and locations in the next TF.

Probabilities of proliferating or death were calculated to trigger these processes. Cancerous cells were simulated by setting the likelihood of proliferation higher than the likelihood of death to generate a tumor growth model.

This simulation, by controlling each cell E c , the size and traction force and the ECM elastic modulus value, makes it possible to examine numerous conditions and variables to investigate mechanotaxis-related phenomena and effects.

Results and discussion

This section reports the simulation results for situations such as:

-

The two cell problem (2D).

-

Different cells with different ECM (2D + 3D).

-

Tumor growth.

Other situations can also be modeled using this simulation such as wound healing, apoptosis, etc.

The two cell problem

Let us review the simple problem of two cells on the same ECM. Placing two cells at a distance from each other, but within a detection range d, will result in the cells moving towards each other.

Figure 6a shows the distance between the centers of the cells in time, for several E s values, without stochastic movement—only mechanotaxis (Pmp = 0). The movement is smooth, and is directly towards collision, since the cells “pull” each other. The stiffer the ECM, the smaller the strain energy density and MDS distance, until the cells cease to collide at all (at 20 kPa, the small variations are from random movements which occur under zero strain energy) at high E s (30 kPa); both the random velocity and mechanotaxis induced velocity are nearly zero.

Two cells problem—the figures shows the distance between the centers of two cells as a function of time. a is for non-stochastic movement (Pmp = 0), and for several ESM elastic modulus values. As the elasticity of the substrate increases, cell velocity decreases; b shows how the movement changes with the addition of stochastic movement for different values of Pmp, and indicates that as the free movement takes over, the interaction weakens. Results are similar to Vermolan and Gefen [4]

Figure 6b depicts the same process, with the addition of stochastic movement, for different Pmp (Es = 10 kPa). It shows the time difference between cells that move mostly by themselves (Pmp = 0.9) and cells moving under mechanotaxis effects (Pmp = 0 or 0.1).

For both simulations, the starting distance was chosen to be 9.6 μm. A larger distance or a change in the ECM elastic modulus will make the signal weaker than the MDS and the cell will wander (solid and dashed lines in Fig. 6a). An analytical solution to this problem is presented in [4].

These results illustrate the basic movement in the model, and the conflicts between mechanotaxis versus other types of movement (stochastic in our example) and between different elastic moduli of the substrate. Changing the cells type will change the cell velocities, according to Eq. (10).

Two cells, two substrates

Here we investigate two ECM regions with two different types of cells as formulated in Eq. 16. The simulation showed that cells with different E c have much more influence on the mechanotaxis process than the E s value of the substrate. The E s and E c values were selected based on Fig. 4 so that the velocities of the cells would be different. The choice of E s controls the rate of the cells’ movement, as the simulation suggests. Figures 7, 8 show the dynamics of these situations in 2D simulations.

2D simulation of cells on different E s and the same E c . in a the left side (blue cells) with E s = 0.5 kPa, right side (red cells) with E s = 10 kPa. In b left side (blue cells) with E s = 3 kPa, right side (red cells) with E s = 7 kPa. E c = 0.5 kPa. Cells on lower E s have greater velocities. It is hard to decide which side was more “attractive” to the cells as in both runs there was a slight migration in each kind of cell

2D simulation of cells on different E c and same E s . a shows E s = 3 kPa, right-side (blue) cells are with E c = 0.5 kPa, left-side (red) cells are with E c = 1 kPa. In b, E s = 10 kPa, E c of right-side (red) cells have E c = 1 kPa, left-side (blue) cells have E c = 0.5 kPa. Attraction towards the side of the lower E c is seen in both simulations, displaying the strong effect of the cells’ elasticity on the migration process

This behavior can be accounted for by looking at Eqs. 10 and 12; cells on the lower E s side (left side on Figs. 7, 8) have greater velocities than cells on the higher E s side; hence, there is a greater likelihood for these cells to migrate to the higher E s side. Furthermore, cells on the lower E s will have a higher maximal distance for MDS (d) than cells on higher E s , since these cells receive more signals from the other zone and will be drawn over.

Throughout the simulations, softer types of cells migrated towards the region crowded with stiffer type cells; i.e., high E c . When comparing the same cells on different ESM, the cells appear to spread with a slight movement towards the stiffer region; i.e., high E s . Figure 9 shows this effect, and depicts the number of cells that migrated to (Fig. 9a) or from (Fig. 9b) an E c = 0.5 kPa to another E c zone.

The figures show the effect and magnitude of a cell’s own elastic modulus (E c ). In this simulation run, the substrate was divided into two halves: one with cells having E c = 0.5 kPa and the other with changing E c values. a shows the number of cells that migrated to the constant elastic modulus side. b shows the number of cells that migrated to the changing E c side. All simulations were carried out for several E s values. The graphs show the impact of the E c value, over E s

One half consisted of cells with a constant E c of 0.5 kPa, and the other half was made up of cells with E c ranging from 0.1 to 1.1 kPa. The cells ‘preferred’ to drift towards the stiffer cell zone with little influence of substrate stiffness. Note that the effectiveness of E s virtually vanishes when dealing with large E c cells.

Metastasis

One of the most interesting situations that this simulation can reflect is metastasis, where a cell becomes malignant and reproduces faster until it extends to another region. In terms of mechanotaxis, cells with different amounts of stiffness migrate towards another ECM region.

To simulate this, we used a 3D simulation by creating two blocks of cells, and ran data mimicking the metastasis process Figs. 10, 11 presents the results of 3D simulations run as in “Two cells, two substrates” with different E s or E c values. Figure 10 is for two ESM regions with the same E c , and Fig. 11 is for different types of cells (different E c ) in the same ESM medium.

3D Simulation runs of cells within different E c and identical E s . In a upper half (red) of E s = 0.5 kPa, lower half (blue) is E s = 10 kPa. E c = 0.5 kPa. In b upper half (red) E s = 3 kPa, lower half (blue) E s = 7 kPa. And E c = 1 kPa. Both simulations depict how the E s value primarily affects the velocity and spread of the cells over time, whereas the choice of E c can have a greater effect on cell migration

3D Simulation run of cells with different E c values within the medium with E s = 10 kPa. The upper half (red) cells have E c = 1 kPa, and lower half (blue) cells have E c = 0.5 kPa. Note that the spread of the cell is high due to the high velocity, and the clear-cut migration towards the cells with higher elasticity

These runs served to compare the 3D simulation to the 2D. Figure 12 shows the process of metastasis by a cancerous cell (red cells) proliferating uncontrollably and growing towards other region. The results show that the simulation in 3D behaved as expected, and was similar to the 2D simulations, with the exception of the amount of time it took for the migration to occur. This temporal difference can be explained by looking at the number of cells in a zone, and the extra degree of freedom a cell can move in, since the cells can attract a cell with a stronger force from more directions than in 2D. The main difference between Fig. 10a, b is the elasticity of the cells, in that the cells’ velocity in Fig. 10b is higher, which increases their likelihood of migrating towards the other type of cells. The magnitude of E c over E s was consistent in 3D as well as in the 2D simulations.

Figure 12 shows the attraction of the tumor towards the upper tissue. Tweaking with the elasticity values can produce a full metastasis simulation. Note that both q (likelihood of proliferation) and p (likelihood of death) play a crucial role.

Cell death (black cells in the simulation) impacts the balance of the proliferation rate, and can potentially influence the migration direction.

Discussion

We presented a novel mechanotaxis model and simulation results. Cell and substrate elastic moduli were shown to have a considerable influence on the way that cells are able to move (movement rate and direction) as well as on culture migration behavior, which can start with only one cell. To understand the parameters controlling mechanotaxis, several simulations were run in order to disentangle these parameters. The data show that the ratio between the elastic modulus of the substrate and the cell, \(\lambda\), primarily influences the cells’ ability to migrate.

As shown in Eq. 10, the cell’s velocity is defined by \(\lambda\), and by selecting this correctly, we can manipulate cell movement on the basis of their elasticity, and culture them on a chosen substrate. \(\lambda\) also affects the migration time, by making the length of the simulation time-step an important parameter. Another effect of \(\lambda\) is the directivity of the migration. The results of the two elastic region simulations (“Two cells, two substrates”) show that stiffer cells produce a “louder” signal and softer cells will migrate towards them. A stiffer substrate will also influence cell movement, and cells will often tend to migrate towards the stiffer side of the substrate. An in vitro experiment [6] motivated the original assumption.

The model incorporated stochastic behavior to make the simulation more realistic and enable spontaneous migration to take place. Without free movement, the cells would be encapsulated in one region without migration. Enabling stochastic movement lengthens the simulation time (Fig. 6), and the ratio between mechanotaxis and self-inflicted movement (Pmp) needs to be calibrated for the simulation to mimic reality. Running the simulation in 2D or 3D alters the length of the simulation as a result of the number of cells and the third degree of freedom of movement.

Proliferation and cell death can affect simulation duration and migration behavior, depending on their rates. As cells multiply more often, a cluster of cells can separate from the main tissue and migrate towards a stiffer region, mimicking the metastasis process (Fig. 12). Here, we chose to manipulate the cells one cell at a time, in an attempt to simulate the connections between the cells, and the response of each cell to the signals it receives individually. Therefore the run-time of this simulation was dependent to a great extent on the number of cells (and hence on the proliferation and cell-death rate), and on the elastic modulus, through the threshold parameter \(\varepsilon\). Running this simulation on a powerful computer, coding it in another language such as C or C++ or running the program in a parallel computational environment such as a GPU (Graphical Processing Unit) would considerably shorten the run-time and make it possible to investigate more complex situations and different parameters.

Conclusion

The model introduced here focused on cell mechanotaxis, to analyze the connection and influence between the cellular substrate, the extracellular matrix and cell stiffness. Our goal was to assess collective effects and migration patterns of cell-to-cell “mechanical communication”.

The findings indicate that cells tend to migrate to stiffer regions. The rate of migration is dependent on cell elasticity and the ability to move freely. These findings have implications for tissue growth, since the growth rate can be altered. We also showed that the model can simulate other biological processes such as tumor development and metastasis, where cell migration plays an important role. For instance, this could be applied to develop medication for faster wound healing or inhibiting migration to prevent metastasis from forming.

This framework can easily be extended to incorporate different types, sizes and shapes of cells, migration mechanisms such as chemotaxis, responses to obstacles, resource scavenging, etc., to investigate their affects on migration process.

References

Pleham RJ Jr, Wang YL. Cell locomotion and focal adhesions are regulated by substrate flexibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:13661–5.

Yeung T, Georges PC, Flanagan LA, Marg B, Ortiz M, Funaki M, Zahir N, Ming W, Weaver VM, Janmey PA. Effects of substrate stiffness on cell morphology, cytoskeletal structure and adhesion. Cell Motil Cytoskelet. 2005;60:24–34.

Califano JP, Reinhart-King CA. Substrate stiffness and cell area predict cellular traction stresses in single cells and cells in contact. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2011;3(1):68–75.

Vermolen FJ, Gefen A. A semi-stochastic cell-based formalism to model the dynamics of migration of cells in colonies. Berlin: Springer; 2011.

Throm Quinlan AM, Sierad LN, Capulli AK, Firstenberg LE, Billiar KL. Combining dynamic stretch and tunable stiffness to probe cell mechanobiology in vitro. Plos One. 2011;6(8):e23272.

Dembo M, Wang YL. Stresses at the cell-to-substrate interface during locomotion of fibroblasts. Biophys J. 1999;76:2307–16.

Dufort CC, Paszek MJ, Weaver VM. Balancing Forces: architectural control of mechanotransduction. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:308–19.

Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, Lakins JN, Rozenbers GI, Gefen A, Reinhart-King CA, Margulies SS, Debmo M, Boettiger D, Hammer DA, Weaver VM. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:241–54.

Ananthakrishnan R, Ehrlicher A. The forces behind cell movement. Int J Biol Sci. 2007;3:303–17.

Mogilner A, Oster G. Cell motility driven by actin polymerization. Biophys J. 1996;71:3030–45.

Winer JP, Chopra A, Kresh JY, Janmey PA. Mechanobiology of cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions. Ch. 2. New York: Springer; 2011. p. 11–22.

Frantz C, Stewart KM, Weaver VM. The extracellular matrix at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:4196–200.

Ng MR, Brugge JS. A stiff blow from the stroma: collagen crosslinking drives tumor progression. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:455–7.

Lu P, Weaver VM, Werb Z. The extracellular matrix: a dynamic niche in cancer progression. JCB. 2012;196(4):395–406.

Geris L, Gersich A, Schugart RC. Mathematical modeling in wound healing, bone regeneration and tissue engineering. Acta Biotheor. 2010;58:355–67.

Lo CM, Wang HB, Dembo M, Wang YL. Cell movement is guided by the rigidity of the substrate. Biophys J. 2000;79:144–52.

Lopez JI, Mouw JK, Weaver VM. Biomechanical regulation of cell orientation and fate. Oncogene. 2008;27:6981–93.

Merkel R, Kirchgeßner N, Cesa CM, Hoffmann B. Cell force microscopy on elastic layers of finite thickness. Biophys J. 2007;93:3314–23.

Asally M, Kittisopikul M, Rué O, Du Y, Hu Z, Çağatay T, Robinson AB, Lu H, Garcia-Ojalvo J, Süel GM. Localized cell death focuses mechanical forces during 3D patterning in a biofilm. PNAS. 2012;109(46):18891–6.

Santini MT, Rainaldi G, Indovina PL. Apoptosis, cell adhesion and the extracellular matrix in the three-dimensional growth of multicellular tumor spheroids. Oncology/Hematology. 2000;36:75–87.

Graner F, Glazier JA. Simulation of biological cell sorting using a two-dimensional extended potts model. Phys Rev Lett. 1992;69(13):2013–6.

Pompe T, Kaufmann M, Kasimir M, Johne S, Glorius S, Renner L, Bobeth M, Pompe W, Werner C. Friction controlled traction force in cell adhesion. Biophys J. 2011;101:1863–70.

Sakamoto Y, Prudhomme S, Zaman MH. Viscoelastic gel-strip model for the simulation of migrating cells. ICES Report; 2011.

Geris L, Liedekerke PV, Smeets B, Tijskens E, Ramon H. A cell based modeling framework for skeletal tissue engineering applications. J Biomech. 2009;43:887–92.

Rienhart-King C, Dembo M, Hammer DA. Cell–Cell mechanical communication through compliant substrates. Biophys J. 2008;95:6044–51.

Discher D, Janmey P, Wang YL. Tissue cells feel and respond to the stiffness of their substrate. Science. 2005;310:1139–43.

Palecek SP, Loftus JC, Ginsberg MH, Lauffenburger DA, Horwitz AF. Integrin-ligand binding properties govern cell migration speed through cell-substratum adhesiveness. Nature. 1997;385(6):537–40.

Gefen A. Effects of virus size and cell stiffness on forces, work and pressures driving membrane investigation in a recptor-mediated endocytosis. J Biomech Eng. 2010;132:084501-1-4.

Johnson KL. Contact mechanics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1985.

Dvir L, Nissim R, Alvarez-Elizondo MB, Weihs D. Quantitative measures to reveal coordinated cytoskeleton-nucleus reorganization during in vitro invasion of cancer cells. N J Phys. 2015;17:143010.

Borau C, Polacheck WJ, Kamm RD, Garcia-Aznar JM. Probabilistic voxel-FE model for single cell motility in 3D. In Silico Cell Tissue Sci. 2014;1(2).

Merks RMH, Koolwijk P. Modeling morphogenesis in silico and in vitro: towards quantitative, predictive, cell-based modeling. Math Model Nat Phenom. 2009;4(4):149–71.

van Oers RFM, Rens EG, LaValley DJ, Reinhart-King CA, Merks RMH. Mechanical cell-matrix feedback explains pairwise and collective endothelial cell behavior in vitro. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10(3):e1003774.

Byrne H, Drasdo D. Individual-based and continuum models of growing cell populations: a comparison. J Math Biol. 2009;58:657–87.

Groh A, Louis AK. Stochastic modeling of biased cell migration and collagen matrix modification. J Math Biol. 2010;61:617–47.

Neilson MP, MacKenzie JA, Webb SD, Insall RH. Modeling cell movement and chemotaxis using pseudopod-based feedback. SIAM J Sci Comput. 2011;33(3):1035–57.

Vermolen FJ. Particle methods to solve modeling problems in wound healing and tumor growth. Comput Part Mech. 2015; doi:10.1007/s40571-015-0055-6.

Authors’ contributions

MD performed the implementation of the modeling into Matlab, he also did the computations, and took the lead in the writing of the manuscript. AG and FJV took part of the supervision of the project and in the writing process. DW revised the manuscript critically and she added important biological context to the results that were obtained. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

MD and AG acknowledge the financial support of the Tel Aviv University. FJV thanks the Delft University of Technology for the financial support. Finally, DW thanks Technion for the funding.

Competing interests

Two of the authors, F. J. Vermolen and D. Weihs are the editors in chief of this journal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Dudaie, M., Weihs, D., Vermolen, F.J. et al. Modeling migration in cell colonies in two and three dimensional substrates with varying stiffnesses. In silico cell tissue sci 2, 2 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40482-015-0005-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40482-015-0005-9