Abstract

Background

Consumption patterns of mushrooms have increased in Ghana recently owing to its acknowledgement as a functional food. Different mushroom cultivation methods and substrate types have been linked to the quality of mushrooms produced, thereby affecting its pricing.

Methods

A comparative regression analysis was carried out to assess the correlation of stipe lengths, cap diameters and biological efficiencies of mushroom fruit bodies of Pleurotus ostreatus cultivated on steam-sterilized and gamma-irradiated sawdust after exposure to ionizing radiations of doses 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 24 and 32 kGy from a 60CO source (SL 515, Hungary) at a dose rate of 1.7 kGy/h. Steam sterilization of composted substrates was also done at a temperature of 100–105 °C for 2 h.

Results

Cap diameters of the mushrooms ranged 41–71.5 and 0–73 mm for gamma-irradiated samples depending on dose and steam-sterilized composted sawdust, respectively. Stipe lengths ranged between 4.4–61 and 0–58.1 for gamma-irradiated samples depending on dose and steam-treated substrates, respectively. Total yields of P. ostreatus grown on the gamma irradiation-treated composted sawdust ranged between 8.8 and 1517 g/kg, while mushrooms from steam sterilized recorded 0–1642 g/kg. Biological efficiencies of mushrooms grown on irradiated sawdust ranged 3–93.3%, while steamed sawdust ranged 0–97%. Good linear correlations were established between the cap diameter and biological efficiency (r2 = 0.70), stipe length and biological efficiency (r2 = 0.91) for mushrooms cultivated on gamma-irradiated sawdust. Similarly, good correlations were established between cap diameter and biological efficiency (r2 = 0.89) stipe length and biological efficiency (r2 = 0.95) for mushrooms cultivated on steam-sterilized sawdust.

Conclusion

These correlations provide the possibility to use only the cap diameter and stipe lengths to predict their biological efficiency and also use this parameter for grading and pricing of mushrooms earmarked for the consumer market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus sp.) have been widely cultivated in many different parts of the world. These mushrooms have the ability to grow at a wide range of temperatures utilizing various lignocelluloses [1] due to its powerful degrading cellulolytic and pectinolytic enzymes produced in vivo. Enzymatic efficiency of mushrooms makes their nutrition one of the most proficient biotechnological processes for lignocellulosic and organic waste recycling [2] by converting plant waste residues from agricultural activities as well as forestry debris. The technology used for its cultivation is eco-friendly since it exploits the natural ability of the fungus to degrade these complex polysaccharides to generate much simple compounds useful for human nutrition.

The current state-of-the-art research shows the usage of fungal biotechnology in fields as restoration of damaged environments (mycorestoration) via mycofiltration (i.e. use of mycelia to filter water), mycoforestry (i.e. use of mycelia to restore forests), mycoremediation (using mycelia to ameliorate heavily polluted soils), myconuclear bioremediation (the use of mycelia to sequester soils of radioactive materials), mycopesticide (use as biopesticide to control pests), and also spent composts could be used as biofertilizers to enhance the fertility of the soil [3, 4]. These methods represent fungal ability to restore the ecosystem where there are no adverse effects after fungal application.

The global economic value of fungi is now well known, the reason for the rise in consumption of mushrooms is a combination of their value as food, and their medicinal and nutraceutical properties [5] hence are gaining so much popularity in Ghana.

Several studies [2, 4, 6, 7] suggest that the methodology described for substrate preparation consists of composting agricultural residues followed by pasteurization and this could be achieved in diverse ways [8, 9]. The steam method is the most popular used for its artificial cultivation [10]. Nonetheless, the conventional method of steam sterilization of substrates has some disadvantages. It is cumbersome since factors such as precise sterilization time and temperature also depend on the residual micro- and mycoflora in a given substrate material [11]. There are also the associated discomfort and health hazards of standing by the heat for long hours not excepting the use of fuel wood for heating when natural cooking gas is not readily available. Fire wood burning depletes the forests of environmentally useful plant species.

Compost substrate sterilization by autoclaving at 121 °C or hot water dipping (pasteurization) in steel drum at 60 °C for 2.3 h has been reported by [12]. Chemical pretreatment of substrates has been reported by [13]. Oyster mushrooms have also been traditionally produced using the outdoor log technique, thereby excluding substrate sterilization [14].

In recent times, gamma irradiation has been used successfully to sterilize different substrates including mushroom compost to cultivate oyster mushrooms in Ghana [4, 15,16,17].

This study was to show correlations of growth parameters (cap diameter and stipe length) and biological efficiency in relation to the use of gamma irradiation for sterilization for substrates for mushroom cultivation.

Materials and methods

Preparation of pure culture

Pure culture was prepared using the modified method of [18]. Malt extract agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampstead, England) was prepared according to manufacturer’s instructions. The media were sterilized in an autoclave for 15 min at 121 °C with 1.5 kg/cm2 pressure. The sterilized media in the test tubes were kept in slanting/sloping positions. The stipe of the mushroom was surface-sterilized with 0.1% sodium hypochlorite. A scalpel was then dipped in alcohol and flamed until it was red hot. It was then cooled for 10 s. The stipe was cut lengthwise from the cap to the tip of the stipe downwards. Small piece of the internal tissue of the broken mushroom was cut and removed with a sterile scalpel. Using an inoculation needle, the cut tissue was then immediately inserted into test tube slant and the tissue laid on the agar surface. The mouth of the test tube was flamed before the needle was inserted. The mouth of the test tube was plugged with cotton wool and was incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for mycelia growth. After 7 days, the tissue was covered with a white mycelium that was spread on the agar surface.

Preparation of spawn

The stock culture substrate was prepared by using good quality sorghum grains and CaCO3 packed tightly in 25 × 18 cm polypropylene bag. These packets were sterilized in an autoclave for 1 h at 121 °C and 1.5 kg/cm2 atmospheric pressure and were kept 24 h for cooling before inoculation. After 7–9 days, there was a complete coverage of running mycelium. The spawn then was ready for inoculation of substrate bags.

Substrate preparation

The substrate consisted of ‘wawa’ (Triplochiton. scleroxylon) sawdust 80–90%, 1–2% of CaCO3 and 5–10% wheat bran. Moisture content was adjusted to 65–70% [19]. The sawdust was mixed thoroughly, heaped to a height of about 1.5 and 1.5 m base and covered with polythene and made to undergo natural fermentation for 28 days. Turning was made every 4 days to ensure homogeneity.

Bagging

Composted sawdust was compressed into 0.18 m × 0.32 m heat-resistant polyethylene bags. Each bag contained approximately 1000 g (1 kg) of substrate and replicated six times.

Sterilization/pasteurization

Bagged composted sawdust substrates were sterilized with either moist heat at a temperature of 100–105 °C for 2.5 h or treated with gamma irradiation.

Gamma irradiation

Bagged composted sawdust substrates were subjected to radiation doses of 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 24 and 32 kGy at a dose rate of 1.7 kGy per hour in air from a cobalt-60 source (SLL 515, Hungary) batch irradiator. Doses absorbed were confirmed using the conventional ethanol-chlorobenzene (ECB) dosimetry system. Radiation was carried out at the Radiation Technology Centre of the Ghana Atomic Energy Commission, Accra, Ghana.

Each treatment dose was replicated six times.

Innoculation and incubation

Each bag was closed with a plastic neck and plugged in with cotton and inoculated with 5 g sorghum spawn. The bags were then incubated at 26–28 °C and 60–65% relative humidity for 20–34 days in a well-ventilated, semi-dark mushroom growth room.

Calculations of growth and yield parameters of mushrooms

Growth and yield parameters were estimated according to methods prescribed by [20,21,22] as follows [6]:

Statistical and regression analysis

Regression analysis of correlation was employed using Microsoft Excel (Windows 10 version). Means of yield and growth parameters were subjected to analyses of variance (one-way ANOVA).

Differences between the means were determined using the Least Significant Difference test. All findings were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

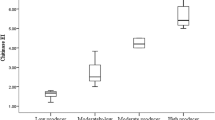

The various substrate treatments resulted in different degrees of growth and yield: stipe length (mm), cap diameter (mm), yields (g/kg) and biological efficiencies (%) (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). Cap diameters of P. ostreatus from gamma-irradiated composted sawdust ranged between 41 and 71.5 mm, while steam sterilized ranged between 0 and 73 mm (Fig. 1). Non-sterilized substrates produced poor growth of mushrooms and were significantly (P < 0.05) low. Cap diameters of mushrooms obtained on steam sterilized were similar with those obtained on 15, 20 and 32 kGy doses. They, however, differed (P > 0.05) statistically.

Stipe lengths of P. ostreatus also ranged between 44 and 61 mm for gamma-irradiated composted sawdust, while that of steam sterilized ranged between 0 and 58.1 mm. Generally, there was no significant (P > 0.05) difference in stipe length growth for both 5 and 10 kGy likewise 20 and 24 kGy doses. Interestingly, steam sterilized and 32 kGy dose produced similar growth and were not significantly (P > 0.05) different.

Biological efficiencies of P. ostreatus from the gamma-irradiated composted sawdust ranged between 3 and 93.3%. Gamma radiation doses of 5, 10, 24 and 32 kGy produced comparable (P > 0.05) biological efficiencies. Similarly, doses of 15 and 20 kGy treatments were also comparable. Steam-sterilized mushrooms recorded a range of 0–97%.

Generally, the average yields of mushrooms recorded were of range 8.8–1517 g/kg for mushrooms depending on dose applied to the substrate, and higher doses tended to yield more mushrooms. A similar trend was observed for biological efficiency and was recorded for the yield. Steam-treated substrates produced a range of 0–1642 g/kg. Although the overall greatest average total yield of mushrooms (1642 g/kg) was obtained from the 5 kGy, the 10 kGy-treated composted sawdust produced comparable results. Yield of steam-sterilized mushrooms recorded was in a similar range as 15 and 20 kGy and showed no significant difference (P > 0.05).

The correlations between biological efficiencies (%) and stipe lengths (mm) as well as cap diameters (mm) of P. ostreatus produced on both gamma irradiation and steam sterilization substrates are presented in Figs. 5, 6, 7 and 8.

There were good correlation coefficients of determinations of r2 = 0.699 (cap diameter) and r2 = 0.914 (stipe length) and biological efficiencies for P. ostreatus from gamma-irradiated sawdust compost (Figs. 5, 6).

Furthermore, the highest scattered points were obtained from correlation of stipe length and biological efficiency (Figs. 5, 6). Very good correlation coefficients were also obtained for cap diameter (r2 = 0.886) and stipe length (r2 = 0.951) on steam-sterilized substrates with biological efficiency (Figs. 7, 8).

Generally, greater stipe lengths and cap diameters (pileus) were attended by high values of biological efficiencies (Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8). Figures 5, 6, 7 and 8 show how the regression line fits the data. The highest coefficients of determination r2 (0.95) were obtained from the regression line between biological efficiency and cap diameter (pileus width). The highest scattered points were obtained from the correlation of biological efficiency and stipe length.

Discussion

Cap diameter (pileus width) and stipe length

Growth parameters of cap diameter and stipe lengths of P. ostreatus obtained on the various treatments of gamma irradiation and steam sterilization varied presumably due to the extent release of nutrients from depolymerization of substrate and subsequent mobilization by hyphae in the substrate for growth.

The performance of oyster mushroom grown on composted lignocellulosic substrates with respect to stipe length and cap diameter (pileus width) also depended on the structure, compactness and physical properties of the substrate which in turn was influenced by the type of agricultural wastes and method used in preparing the substrates. Chukwurah et al. [23] reported that substrates with higher moisture retaining capacity grow better than those with lower moisture retaining capacity and that substrates which contained mixtures of different types of agricultural wastes performed better than those with single agricultural waste [23].

Results of stipe lengths and cap diameters obtained in this experiment agree with findings of some researchers [6, 23, 24]. Conversely, Kortei and Wiafe-Kwagyan [17] reported higher values of 95 and 80 mm for cap diameter and stipe lengths, respectively, for P-31 strains cultivated on gamma-irradiated corncobs when they investigated the growth of P-31 strain on eight different gamma-irradiated substrates. Kortei [24] and Sarker et al. [25] reported a lower range of 1–5 and 1.85–6.57 cm for stipe lengths and cap diameters, respectively.

Yield and biological efficiency

According to [26], biological efficiency (B.E) is an expression of the bioconversion of dry substrate to fresh fruiting bodies and indicates the fructification ability of the fungus exploiting the substrate. Biological efficiencies (65–98%) recorded in this present study were relatively higher than literature values, and our data agree with the findings of Garo and Girma [27] who reported range of 31.98–146% from the study of responses of oyster mushrooms (P. ostreatus) as influenced by different substrates in Ethiopia. Gitte et al. [28] also reported high biological efficiency of milky mushrooms on different substrates which ranged from 51.57 to 146.3%. On the contrary, low B.E (%) values were reported by [6] ranging from 61 to 0% for P. ostreatus on different lignocellulosics. Raymond et al. [24] reported a B.E range of 8.95–62.8% for cultivated oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus HK37) on sisal wastes fractions supplemented with cow dung manure in Tanzania.

Both sterilization methods were effective in decontamination and depolymerisation of substrates as evidenced in the yield as well as biological efficiency since the two are directly linked. Yields were moderately higher for mushrooms cultivated from gamma-irradiated substrates than for those from steam treatment. This observation could be attributed to the higher degree of splitting of complex polysaccharides of the substrates into smaller utilizable units by gamma rays than what obtained for steam. Secondly, gamma rays have a high lethal effect on the genome of the micro-organisms resident in the substrate either directly or indirectly during pasteurization. It can be deduced from our results that 5 kGy produced the overall best yield. This study has confirmed that the use of different doses (5, 10, 15, 20, 24 and 32 kGy) of gamma irradiation to sterilize sawdust substrate produced similar results for that of steam treatment. Although the overall maximum yield was marginally higher for steam-treated substrates, the cost of heating (either with wood, gas or electricity) with steam will be economically more expensive and capital intensive and laborious than the use of gamma irradiation.

Correlations of cap diameter, stipe length and biological efficiency

Varied degrees of growth of P. ostreatus fruit body parts have been observed on different substrates as well as different cultivation methods by some researchers [1, 12]. In this study, there were high coefficients of correlations of stipe lengths and biological efficiency (0.91–0.95) was better as compared to that of cap diameter and biological efficiency (0.69–0.88) for both methods. Ajonina and Tatah [29] reported that the size of the stalk and pileus is positively correlated with yield and with carbohydrate and protein, respectively. They noticed variations in stalk length (2.43–3.24 cm) for P. ostreatus. Ahmed et al. [30] suggested that in the case of yield, the larger the pileus size, the higher the yield. Fruiting body weight is to a large extent influenced by the thickness and diameter of the pileus. Large-sized fruit bodies are widely perceived to be of superior quality and hence highly ranked in mushroom cultivation. In grading oyster mushroom for pricing, the use of correlation of stipe length, cap diameter (pileus width) and weight will be good criteria for grading quality [31].

Shen and Royse [32] and Mondal et al. [18] reiterated that fruit bodies were susceptible to breakage during packing and transport and so reduced their storage quality. Harvested mushrooms packaged in a rigid appropriately determined packaging material with good aeration, humidity and compactness can have extended shelf life even after grading for the market.

Conclusion

Our results showed that there was a positive correlation between cap diameters, stipe lengths and biological efficiencies of P. ostreatus cultivated on both steam-sterilized and gamma-irradiated composted sawdust which gives a clear indication of the possibility to predict yield or biological efficiency with growth determinants. Yields of both methods were also comparable. Gamma radiation could be used as a decontaminating agent of substrates for mushroom cultivation in countries that have access to gamma irradiation facilities to augment the dreary processes associated with the conventional steam sterilization method. Pricing can be based on a quality parameter such as yield, stipe length and pileus width.

Change history

01 June 2018

In the original publication of this article [1], there was an error in an author name. In this correction article the correct and incorrect names are indicated.

References

Sanchez C. Cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus and other edible mushrooms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;85:1321–37.

Mandeel QA, Al-Laith AA, Mohamed SA. Cultivation of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus sp.) on various lignocellulosic wastes. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;21:601–7.

Stamets P. Mycelium running: how mushroom can help save the world. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press; 2005. p. 574.

Kortei NK. Comparative effect of steam and gamma irradiation sterilization of sawdust compost on the yield, nutrient and shelf life of Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.ex. Fr) Kummer stored in two different packaging materials. Ph.D. thesis, Graduate School of Nuclear and Allied Sciences, University of Ghana, Legon. 2015.

Kortei NK, Wiafe-Kwagyan M. Comparative appraisal of the total phenolic content, flavonoids, free radical scavenging activity and nutritional qualities of Pleurotus ostreatus (EM-1) and Pleurotus eous (P-31) cultivated on rice (Oryzae sativa) straw in Ghana. J Adv Biol Biotechnol. 2015;3(4):153–64.

Obodai M, Cleland-Okine J, Vowotor KA. Comparative study on the growth and yield of Pleurotus ostreatus mushroom on different lignocellulosic by-products. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003;30:146–9.

Raymond P, Mshandete AM, Kivaisi AM. Cultivation of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus HK-37) on sisal waste fractions supplemented with cow dung manure. J Biol Life Sci. 2013;4(1):274–86.

Stamets P. Growing gourmet and medicinal mushrooms. Berkley: Ten Speed Press; 1993. p. 552.

Balasubramanya RH, Kathe AA. An inexpensive pre-treatment of cellulosic materials for growing edible oyster mushrooms. Biol Resour Technol. 1996;57:303–5.

Apetorgbor MM, Apetorgbor AK, Nutakor E. Utilization and cultivation of edible mushrooms for rural livelihood in southern Ghana. 17th Commonwealth Forestry Conference. Sri-Lanka. 2005.

Kwon H, Sik Kim B. mushroom growers’ handbook: shiitake cultivation. Mushworld: Seoul; 2004. p. 260.

Oseni TO, Dlamini SO, Earnshaw DM, Masarirambi MT. Effect of substrate pre-treatment methods on oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) production. Int J Agric Biol. 2012;14(2):251–5.

Contreras EP, Sokolov M, Mejia G, Sanchez J. Soaking of substrate in alkaline water as a pretreatment for the cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol. 2004;79(2):234–40.

Royse DJ. Cultivation of shiitake on natural and synthetic logs. 2009. p. 2. http://www.americanmushroom.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Shiitake_how_to_grow_PSU.pdf. Accessed 22 Sept 2017.

Gbedemah C, Obodai M, Sawyer LC. Preliminary investigations into the bioconversion of gamma irradiated agricultural wastes by Pleurotus spp. Radiat Phys Chem. 1998;52(6):379–82.

Kortei NK, Odamtten GT, Obodai M, Appiah V, Annan SNY, Acquah SA, Armah JO. Comparative effect of gamma irradiated and steam sterilized composted ‘wawa’ (Triplochiton scleroxylon) sawdust on the growth and yield of Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.Ex.Fr.) Kummer. Innov Rom Food Biotechnol. 2014;14:69–78.

Kortei NK, Wiafe-Kwagyan M. Evaluating the effect of gamma irradiation on eight different agro-lignocellulose waste materials for the production of oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus eous (Berk.) Sacc. Strain P-31). Croat J Food Biotechnol Nutr. 2014;9(3-4):83–90.

Mondal SR, Rehana MJ, Noman SM, Adhikary SK. Comparative study on growth and yield performance evaluation of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus florida) on different substrates. J Bangladesh Agric Univ. 2010;8:213–20.

Buswell JA. Potentials of spent mushroom substrates for bioremediation purposes. Compost. 1984;2:31–5.

Amin RSM, Alam N, Sarker NC, Hossain K, Uddin MN. Influence of different amount of rice straw per packet and rate of inocula on the growth and yield of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus). Bangladesh J Mushroom. 2008;2:15–20.

Tisdale TE, Susan C, Miyasaka-Hemmes DE. Cultivation of the oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) on wood substrates in Hawaii. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;22:201–6.

Morais MH, Ramos AC, Matos N, Santos-Oliveira EJ. Production of shiitake mushroom (Lentinus edodes) on ligninocellulosic residues. Food Sci Technol Int. 2000;6:123–8.

Chukwurah NF, Eze SC, Chiejina NV, Onyeonagu CC, Okezie CEA, Ugwuoke KI, Ugwu FSO, Aruah CB, Akobueze EU, Nkwonta CG. Correlation of stipe length, pileus width and stipe girth of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) grown in different farm substrates. J Agric Biotechnol Sustain Dev. 2013;5(3):54–60.

Kortei NK. Determination of optimal growth and yield parameters of Pleurotus ostreatus grown on composted cassava peel based formulations. M.sc.Thesis, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana. 2008.

Sarker NC, Hossain MM, Sultana N, Mian IH, Karim AJMS, Amin SMR. Performance of different substrates on the growth and yield of Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacquin ex Fr.) Kummer. Bangladesh J Mushroom. 2007;1:9–20.

Fan L, Pandey A, Mohan R, Soccol CR. Comparison of coffee industry residues for production of Pleurotus ostreatus in solid state fermentation. Acta Biotechnol. 2000;20(1):41–52.

Garo G, Girma G. Responses of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) as influenced by substrate difference in Gamo Gofa zone, Southern Ethiopia. IOSR J Agric Vet Sci. 2016;9(4):63–8.

Gitte VK, Priya J, Kotgire G. Selection of different substrate for the cultivation of milky mushroom (Calocybe indica P&C). Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2014;13(2):434–6.

Ajonina AS, Tatah LE. Growth performance and yield of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) on different substrates composition in Buea South West Cameroon. Sci J Biochem. 2012. https://doi.org/10.7237/sjbch/139.

Ahmed M, Abdullah N, Ahmed KU, Borhannuddin Bhuyan MHM. Yield and nutritional composition of oyster mushroom strains newly introduced in Bangladesh. Pesqui Agropecu Bras. 2013;48(2):197–202.

Onyango BO, Palapala VA, Arama PF, Wagai SO, Gichimu BM. Suitability of selected supplemented substrates for cultivation of Kenyan native wood ear mushrooms (Auricularia auricula). Am J Food Technol. 2011;6:395–403.

Shen Q, Royse D. Effect of nutrient supplement on biological efficiency, quality and crop cycle time on maitake (Griofola frondosa). Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;57:74–8.

Authors’ contributions

NKK, GTO and MO involved in the conception of the research idea, design of the experiments and data analysis and also drafted the paper. MW-K and DLNM involved in the design of the experiments and data collection. GTO and MO provided guidance, corrections and supervision to the entire research and critically reviewed the manuscript. NKK and GTO read, reviewed and amended the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript..

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Messers Abaabase Azinkaba, Godson Agbley and Moses Mensah of Mycology Unit, CSIR-FRI, for under taking the steam sterilization and maintenance of the farm house. Messers S.N.Y. Annan, J.N.O. Armah, S.W.N.O. Mills and S.A. Acquah of the Radiation Technology Centre, Ghana Atomic Energy Commission (G.A.E.C), Kwabenya, Accra, carried out the irradiation process.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of supporting data

The data sets used and analysed during the current study are available to readers as in the manuscript.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The original version of this article was revised: the name of one of the authors had been spelled incorrectly. It should be Deborah Louisa Narh Mensah, not Deborah Louisa Narh-Mensah

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kortei, N.K., Odamtten, G.T., Obodai, M. et al. Correlations of cap diameter (pileus width), stipe length and biological efficiency of Pleurotus ostreatus (Ex.Fr.) Kummer cultivated on gamma-irradiated and steam-sterilized composted sawdust as an index of quality for pricing. Agric & Food Secur 7, 35 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-018-0185-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-018-0185-1