Abstract

Our aim in this paper is presenting an attractive numerical approach giving an accurate solution to the nonlinear fractional Abel differential equation based on a reproducing kernel algorithm with model endowed with a Caputo–Fabrizio fractional derivative. By means of such an approach, we utilize the Gram–Schmidt orthogonalization process to create an orthonormal set of bases that leads to an appropriate solution in the Hilbert space \(\mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\). We investigate and discuss stability and convergence of the proposed method. The n-term series solution converges uniformly to the analytic solution. We present several numerical examples of potential interests to illustrate the reliability, efficacy, and performance of the method under the influence of the Caputo–Fabrizio derivative. The gained results have shown superiority of the reproducing kernel algorithm and its infinite accuracy with a least time and efforts in solving the fractional Abel-type model. Therefore, in this direction, the proposed algorithm is an alternative and systematic tool for analyzing the behavior of many nonlinear temporal fractional differential equations emerging in the fields of engineering, physics, and sciences.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The area of fractional calculus is an active interesting dynamic branch of theoretical and applied mathematical analysis, quantum mechanics, engineering. and physical sciences. The original idea of fractional calculus dates back to a question of L’Hospital at the end of the seventeenth century, whose text was about the noninteger-order derivative of a function. Despite the early discovery of the fractional order derivatives, which generalizes the foundations and principles of the classical calculus analysis, applied scientists were not latterly aware of the fact that they could mathematically make use of the fractional calculus in modeling the real-life situations. During the past few decades, an interest of mathematicians has been focused on developing operators of fractional derivatives and some applications in dealing with solutions of the generalized classic differential equations, knowing the effect of the fractional conditioning on the quality of the established models [1–4]. This trend contributed a lot to the emergence of a number of fractional derivative definitions such as Riemann–Liouville, Caputo, Marchaud, Erdélyi–Kober, Feller, Atangana–Baleanu, Grünwald–Letnikov, Sonin–Letnikov, Hadamard, and so forth [5–9]. Anyhow, it has been shown through numerous studies on fractional analysis that different definitions are equivalent under certain circumstances. This variety of differential and integral fractional operators provides the opportunity to choose the most suitable one according to the problem associated with the initial and boundary conditions to obtain the optimal solution to the studied problem. Although these definitions are well known and widely used, they have some flaws and limitations and sometimes fail to differentiate the functions, as in the chain, quotient, and Leibniz rules, in addition to some having a singular kernel. Nevertheless, the Caputo concept possesses several interesting features and allows traditional initial and boundary conditions to be included in the problem formulation. Therefore some modern concepts were developed based on the Caputo sense, among which the Atangana–Baleanu–Caputo derivative, Caputo–Fabrizio derivative, and Caputo k-fractional derivatives. Caputo and Fabrizio [10] introduced a novel concept of the fractional derivative, known as the Caputo–Fabrizio fractional derivative, which contains a nonsingular exponential kernel that leads to better modeling of real-world problems. Since then, the Caputo–Fabrizio and Atangana-Baleanu-Caputo (ABC) concepts have witnessed an increasing demand from scholars to conduct numerous analytical and applied studies in various scopes of engineering, physics and pure mathematics [11–18].

From a historical point of view, Abel-type dynamic equations date back to the Norwegian mathematician Niels Abel while studying the theory of elliptic functions. Depending on the context, Abel differential equations of the first and second kinds are one of the most important nonlinear nonhomogeneous equations having a long history and various applications in physics, chemistry, biology, medicine, and epidemiology, including fuel mechanics, magnetic statistics, solid mechanics, thin film condensation, and medium problems [19, 20]. For completeness, we also stress that Abel differential equations find applications in probability when full moment problems are involved and, moreover, partial and pseudodifferential equations also very suitably fit in the modeling of real phenomena like those aforementioned; see [21–24]. Furthermore, they are a generalization of the common Riccati and Bernoulli differential equations and of a particular class of logistic differential equations. In many situations, nonlinear partial differential equations that have unpredictable solution behaviors can be reduced to a class of Abel differential equations. Using some integrability terms of Abel equation, various classes of traveling wave and soliton solutions to nonlinear partial evolution equations can be obtained. For further illustration, exact-form solutions of certain types of the Schrödinger equation, Fisher–Kolmogorov equation, Newell–Whitehead equation, FitzHugh–Nagumo equation, and Pochhammer–Chree equation can be achieved using standard integrability conditions for Abel differential equations with high efficiency compared to direct conventional methods [25].

In this analysis, we employ the reproducing kernel algorithm (RKA) for investigating numerical solutions for a class of nonlinear fractional Abel differential equations (FADE) of both kinds in the sense of Caputo–Fabrizio derivative. More specifically, we consider the following nonlinear FADE of the first kind:

where \(a \leq t \leq b\), \(p_{3}(t)\neq 0\), and \(p_{2}(t)\), \(p_{1}(t)\), and \(p_{0}(t)\) are meromorphic functions in temporal direction x. Also, we consider the following nonlinear FADE of the second kind:

along with the initial condition

where \(\omega _{0}\) is a real constant, and \(a \leq t \leq b\). For aforesaid equations, \(\omega (t)\in \mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\) is an unknown analytic function to be solved, and \({}^{\mathcal{CF}}\mathcal{D}_{a}^{\alpha }\) is a differential operator of order α in the Caputo–Fabrizio sense. More descriptively, when \(p_{2}(t)= 0\) and \(p_{0}(t)=0\), the first-kind FADE (1.1) reduces to the fractional Bernoulli differential equation, and when \(p_{3}(t)= 0\), it reduces to the fractional Riccati differential equation. Using the substitution \(\omega (t)=\frac{1}{\omega (t)}\), the first-kind FADE can be transformed into the second-kind FADE [26]. These models are obtained by replacing the classical-order derivative for the ordinary Abel differential equation by the fractional-order derivative in the Caputo–Fabrizio sense. For more detail on fractional versions of Abel differential problems using various fractional operators, we refer the reader to [27–30] and the references therein.

In general, the exact-form solutions of several classes of ordinary Abel DEs and FADEs of a cubic or higher order are rare and missing in the literature, and only specific approximate solutions are provided. However, the importance of the Abel DEs often coincides with the inability to find an analytical solution due to the complexities involved. Hence the urgent need is developing efficient numerical methods to obtain approximate analytical solutions for these types of dynamic differential equations. For instance, the short-memory principle technique is also applied to compute approximate solutions for the first- and second-kind fractional Abel differential equations with Grünwald–Letnikov operator [28]. The operational matrix method [27] is proposed, depending on Genocchi polynomials, to solve both kinds of the fractional Abel differential equations in the Caputo sense, whereas the homotopy analysis method [26] is used to obtain approximate solutions of the fractional Abel differential equations in the Caputo sense. In [29], the spectral and Newton–Krylov subspace methods are implemented based on generalized Bessel functions to handle the first-kind fractional Abel differential equations in the Riemann–Liouville sense. On the other aspect as well, to deal with the ordinary Abel differential equations, several mathematical methods can be found in [31–33] and the references therein. The main contribution of this work is developing RKA to numerically solve the nonlinear FADEs of both kinds in the Hilbert space \(\mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\).

Nevertheless, RKA is among the most accurate and effective numerical approximate methods, which have wide applications in various fields of applied sciences [34–40]. In recent years, researchers have devoted a lot of efforts and attention to understanding the advanced implementation procedures and the characteristics of the RK method as well as its applications to various scientific models due to its capacity, potential, and distinctive properties. Among these advantages, it is specifically designed for working with nonlinear differential equations to obtain accurate solutions with less time effort and infinite precision along the entire respective domain. This method also ensures a rapid convergence of solutions, in which approximate solutions uniformly converge to the exact solutions in the concerned Hilbert space, in addition to the adaptive ability to deal with fractional operators and easily fit any changes to the model. For more detail, we refer to [41–47].

This research is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we review several properties of the Caputo–Fabrizio (CF) derivative. In Sect. 3, we describe the reproducing kernel Hilbert spaces with some important theories. Section 4 is devoted to the implementation of the RK algorithm to deal with a nonlinear FADE under the CF-derivative. In Sect. 5, we discuss the stability and convergence of the proposed method. Numerical examples are given in Sect. 6 to demonstrate the reliability and efficiency of the RKA method. This analysis ends with a brief conclusion.

2 CF-derivative and preliminaries for reproducing kernel spaces

In this section, we consider a fractional version of differentiation operators without singular kernel, the Caputo–Fabrizio fractional derivative, equipped with some preliminary facts. Such a novel update provides the more recent and accurate interpretation of the real-life situations compared to various previous releases. The Caputo fractional and Caputo–Fabrizio fractional derivatives are read as follows.

Definition 2.1

([40])

The Caputo fractional derivative of a differentiable function ω(t) is defined as

where \(\alpha \in [0,1)\), \(t>a\), and Γ is the special gamma function.

Despite the widespread use of the aforesaid definition, it has some limitations and obstacles when modeling some physical phenomena whose effects and setbacks are clearly negative regarding the accuracy of the calculation and results. Much of this deficiency is limited to the fact that Caputo’s definition possesses a singular kernel. Therefore a novel version of the fractional differential operator has been introduced by Caputo and Fabrizio in 2015. The idea of this novel operator is replacing the singular kernel in Caputo’s operator with a regular exponential one, which has the ability to work effectively with the phenomenon accurately and correctly. Such modification improves the quality of the calculation and results [12].

Definition 2.2

([10])

For \(0<\alpha \le 1\), let ω(t) be a function in the usual Sobolev space over \([a,b]\), that is, \(\omega(t)\in \mathcal{H}[a,b]\). Then the fractional order of the Caputo–Fabrizio derivative (CF-derivative) is defined as

where \(\mathcal{M(\alpha )}\) is the normalization function, depending on α, such that \(\mathcal{M}(0)=\mathcal{M}(1)=1 \).

It is proper to mention that an explicit formula when \(\mathcal{M(\alpha )}=\frac{2}{2-\alpha }\) is provided in [11] so that the CF-derivative, referred to in (2.1), can be equivalently converted into

Definition 2.3

([11])

For \(0< \alpha \leq 1\), let \(\omega (t)\in \mathcal{H}[a,b]\). Then, the fractional integral of \(\omega (t)\) corresponding to the CF-derivative of order α is defined as

Let us now introduce certain interesting properties of the CF derivative:

-

1.

The CF-derivative of any constant is zero, that is, \({}^{\mathcal{CF}}\mathcal{D}^{\alpha }_{a}M=0\), ∀ \(M\geq 0\).

-

2.

The CF-derivative is a linear operator, that is,

$$ {}^{\mathcal{CF}}\mathcal{D}^{\alpha }_{a}\bigl(\lambda _{1}\omega _{1}(t)+\lambda _{2} \omega _{2}(t)\bigr)=\lambda _{1}{}^{\mathcal{CF}} \mathcal{D}^{\alpha }_{a}\omega _{1}(t)+ \lambda _{2}{}^{\mathcal{CF}}\mathcal{D}^{\alpha }_{a} \omega _{2}(t). $$ -

3.

For \(0<\alpha \leq 1\) and \(\omega \in \mathcal{H}[a,b]\), we have

$$ \bigl({}^{\mathrm{CF}}\mathcal{I}_{a}^{\alpha }\bigr) \bigl({}^{\mathcal{CF}}\mathcal{D}^{\alpha }_{a}\bigr)\omega (t)= \omega (\xi )-\omega (a). $$ -

4.

For \(0<\alpha \leq 1\), the CF-derivative of order \(\alpha +n\) is defined for \(n\in N\) as

$$ {}^{\mathrm{CF}}\mathcal{D}^{\alpha +n}_{0}\omega (t)= {}^{\mathcal{CF}}\mathcal{D}^{\alpha }\bigl( \mathcal{D}^{(n)}_{a} \omega (t)\bigr) = \frac{1}{1-\alpha } \int ^{t}_{a} \omega ^{(n)}(s) \exp \biggl[{\frac{-\alpha (t-s)}{1-\alpha }}\biggr]\,ds. $$

Now, to solve the nonlinear FADEs (1.1)–(1.3) in the Hilbert space \(\mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\), we build two reproducing kernel functions.

Definition 2.4

([36])

Let \(\mathcal{W}\) be the Hilbert space consisting of all functions defined on a nonempty set Ω into \(\mathbb{C}\). Then \(\mathcal{W}\) is a reproducing kernel Hilbert space (RKHS) if for every \(t\in \Omega \), the evaluation function \(\delta _{t}(f)=f(t)\) is bounded in \(\mathcal{W}\).

Definition 2.5

([36])

Let \(\mathcal{W}\) be an RKHS defined in a nonempty set Ω. Then there exists a unique \(\mathcal{R}(\cdot ,t)\in \mathcal{W}\) such that \(\langle f(\cdot ),\mathcal{R}(\cdot ,t)\rangle =f(t)\) for each \(f \in \mathcal{W}\).

Definition 2.6

([36])

Let Ω be a nonempty abstract set, and let \(\mathcal{W}\) be an RKHS. Then a function \(\mathcal{R}:\Omega \times \Omega \longrightarrow \mathbb{C}\) defined as \(\mathcal{R}(t,s)=\mathcal{R}_{t}(s)\) is called a reproducing kernel function (RKF) of the space \(\mathcal{W}\).

The kernel function possesses some important properties of being unique representation, conjugate symmetric, and positive-definite.

Definition 2.7

([41])

The reproducing kernel space \(\mathcal{H}^{1}[a,b]\) is defined by

The inner product and norm associated with the space \(\mathcal{H}^{1}[a,b]\) are given as

The unique representation of the reproducing kernel \(\mathcal{R}_{t}(s)\) of \(\mathcal{H}^{1}[a,b]\) is

Definition 2.8

([41])

The reproducing kernel space \(\mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\) is defined by

The inner product and norm associated with the space \(\mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\) are given as

The unique representation of the reproducing kernel \(\mathcal{K}_{t}(s)\) of \(\mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\) is given as

3 RKA for solving FADEs under CF-derivative

In this section, the RK implementation method is applied to solve the nonlinear FADEs (1.1)–(1.3) of both kinds in the sense of CF-derivative. Meanwhile, some related lemmas and theories are provided to create analytical and approximate solutions of the FADEs in the space \(\mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\). First, define the linear operator

by

On the other hand, by introducing the simple transformation \(\omega (t):=\omega (t)-\omega _{0}\) to homogenize the initial condition (1.3), the FADEs (1.1)–(1.3) can be equivalently rewritten as

where \(\mathcal{N}_{\sigma }(t,\omega (t))\), \(\sigma =1,2\), are the nonlinear terms of both kinds of the FADEs such that \(\mathcal{N}_{1}(t,\omega (t))= p_{3}(t)\omega ^{3}(t)+ p_{2}(t) \omega ^{2}(t)+ p_{1}(t)\omega (t)+ p_{0}(t)\) and \(\mathcal{N}_{2}(t,\omega (t))= \omega ^{-1}(t)(p_{0}(t)\omega ^{3}(t)+ p_{1}(t)\omega ^{2}(t)+ p_{2}(t)\omega (t)+ p_{3}(t))\), where \(\omega (t) \in \mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\) and \(\mathcal{N}_{k}(t,\omega (t))\in \mathcal{H}^{1}[a,b]\).

To apply the proposed algorithm for solving (3.1) in the space \(\mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\), we need the following theorems.

Theorem 3.1

The linear fractional differential operator \(\mathcal{L}:\mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\longrightarrow \mathcal{H}^{1}[a,b]\) is bounded.

Proof

To show the boundedness of the operator \(\mathcal{L}\), we have

By the RK property of \(\mathcal{R}_{t}(s)\) on the space \(\mathcal{H}^{1}[a,b]\) and the continuity of \(\mathcal{R}_{t}(s)\) and \(\mathcal{R'}_{t}(s)\) on \([a,b]\) there exist constants \(K_{1}\), \(K_{2}\) such that \(\|\frac{\partial ^{i}({}^{\mathrm{CF}}D_{a}^{\alpha }\mathcal{R}_{t}(s))}{\partial t^{i}} \Vert ^{2}_{\mathcal{H}^{2}}\leq K_{i}\), \(i=1,2\). Consequently, we get

where \(K=\max\{K_{1},K_{2}\}\). □

Without loss of generality, hereunder are the steps to create an orthogonal basis system of the space \(\mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\):

-

Take a countable dense subset \(\{t_{i}\}_{i=1}^{\infty }\subset [a,b]\).

-

Define the function \(\Phi _{i}(\cdot )=\mathcal{R}_{t_{i}}(\cdot )\).

-

Put \(\Psi _{i}(\cdot )=\mathcal{L}^{\star }\Phi _{i}(\cdot )\), where \(\mathcal{L}^{\star }\) is the adjoint operator of \(\mathcal{L}\).

Hence by means of the Gram–Schmidt orthogonalization process for \(\{\Psi _{i}(\cdot )\}_{i=1}^{\infty }\) the normalized basis system \(\{ \widehat{\Psi }_{i}(\cdot ) \}_{i=1}^{\infty }\) can be given as

Therefore the procedure of obtaining the orthonormal coefficients \(\beta _{ik}\) of (3.2) can be illustrated by Algorithm 1.

Theorem 3.2

If \(\{t_{i}\}_{i=1}^{\infty }\) is a dense set on \([a,b]\), then the orthogonal function system \(\{ \Psi _{i}(t) \}_{i=1}^{\infty }\) is complete in \(\mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\), and \(\Psi _{i}(t)= \mathcal{L}_{s}\mathcal{K}_{t}(s)| _{s=t_{i}}\).

Proof

Note that

Let us show the completeness of the orthogonal basis system \(\{ \Psi _{i}(t) \}_{i=1}^{\infty }\) in \(\mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\). For each fixed \(\omega (t)\in \mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\), letting \(\langle \omega (t),\Psi _{i}(t)\rangle _{\mathcal{H}^{2}}=0\) for \(i=1,2,\ldots \) , we have

Since \(\{t_{i}\}^{\infty }_{i=1}\) is dense on \([a,b]\), we have \(\mathcal{L}\omega (t)=0\). Therefore \(\omega (t)=0\) by the existence of the inverse operator \(\mathcal{L}^{-1}\). □

Lemma 3.3

The orthonormal basis system \(\{ \widehat{\Psi }_{i}(t)\}_{i=1}^{n} \) in \(\mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\) is linearly independent.

Proof

Let \(\{ \widehat{\Psi }_{i}(t)\}_{i=1}^{n}\) be an orthonormal basis sequence. Then

Multiplication by a stationary \(\widehat{\Psi }_{j}(t)\) gives

When n tends to infinity, the proof is similar. □

Theorem 3.4

If \(\{t\}_{i=1}^{\infty }\) is dense on \([a,b]\) and \(\omega (t)\in \mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b] \) is the exact solution of the FADE (3.1), then \(\omega (t)\) can be represented as

where \(\Pi _{i}=\sum_{k=1}^{i}\beta _{ik}\mathcal{N}_{\sigma }(t_{k}, \omega (t_{k}))\), \(\sigma =1,2\), and \(\beta _{ik}\) are the orthogonalization coefficients.

Proof

For each \(\omega (t)\in \mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\) and for any complete orthonormal sequence \(\{ \widehat{\Psi }_{i}(t)\}_{i=1}^{n}\) on \(\mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\), the function \(\omega (t)\) can be expressed as the form of the Fourier series expansion \(\sum_{1=1}^{\infty }\langle \omega (t),\widehat{\Psi }_{i}(t)\rangle _{ \mathcal{H}^{2}} \widehat{\Psi }_{i}(t)\), which is a convergent series in the sense of \(\|\cdot\|_{\mathcal{H}^{2}}\). Therefore we obtain

□

To obtain an approximate solution \(\omega _{n}(t)\) of the nonlinear FADEs of both kinds, we define the n-term truncated solution of the analytical solution \(\omega (t)\) with coefficients \(\Theta _{i}\) as follows

In fact, the solution of the nonlinear FADE is fixed and depends on the appropriate choice for the initial condition.

4 Stability and convergence analysis of the RKA

In this section, we investigate the stability and convergence of the proposed method to solve the nonlinear FADEs (1.1)–(1.3) in the space \(\mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\).

Theorem 4.1

Suppose that \(\mathcal{N}_{\sigma }(t,\omega (t))\) satisfies the Lipschitz condition with respect to \(\omega (t)\):

where K is the Lipschitz coefficient. Then the iterative sequence (3.3) converges if \(K<\| \mathcal{L}\| _{\infty }\).

Proof

From the Lipschitz condition we have

where \(\|\omega (t)\|_{\infty } = \sup_{t\in [a,b]}|\omega (t)| \). By (3.1) we can write

Letting \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), we have

Thus, for \(m,n \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \(m>n\),

So, for any \(\epsilon >0\), there exist \(m>n>p\) such that \(\|\omega _{m}-\omega _{n}\|_{\infty }<\epsilon \). This shows that \(\omega _{n}\) is a Cauchy sequence and hence converges. □

Now we discuss the stability of the proposed method for the solution of the nonlinear FADEs. To do this, we need the following lemma.

Lemma 4.2

If \(\omega (t)\in \mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\), then there exists a constant \(M>0\) such that

where \(\| \omega \|_{ \infty }= \sup \{ |\omega (t)| t \in [a,b]\}\).

Proof

Letting \(\omega ^{(i)}(t)\in \mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\), \(i=0,1\), we have

□

Theorem 4.3

If the nonlinear FADE (3.1) has a unique solution, then the solution achieved by the RK method is stable.

Proof

Assume that \(\omega _{n}(t)\in \mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\) is an approximate solution of Eq. (3.1) of the form

and assume that

is an approximate solution of \(\mathcal{L}\omega (t)=\mathcal{N}_{\sigma }(t,\omega (t))+\epsilon (t)\), where \(\epsilon (t)\) is small bounded perturbation. We will prove that there exists \(\delta >0\) such that \(\| \omega _{n}-\omega _{n}^{*}\| _{\infty }<\delta \). To show this, note that

On the other hand, since \(\mathcal{L}^{-1}\) exists and \(\mathcal{L}^{-1}\epsilon (t)\in \mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\), we obtain

Hence, comparing (4.4) and (4.5), we get

Since \(\mathcal{L}^{-1}\) is continuous on \([a,b]\), there exists \(c>0\) such that \(\|\mathcal{L}^{-1}\|_{\mathcal{H}^{2}}\leq c \). Therefore we have

Finally, this gives

Thus taking \(\delta =c M \|\epsilon (t)\|_{\mathcal{H}^{2}}\) completes the proof of the theorem. □

5 RKA simulations for the nonlinear FADEs

To ensure the effectiveness and efficiency of the modified RK method in solving the nonlinear FADEs and the effect of using the CF-derivative on the quality of calculations and processing time, in this section, we conduct some numerical examples for both kinds of the FADEs within the CF-derivative. Indeed, the exact solutions to these examples are somewhat difficult to be obtained even for the integer-order derivative, and only approximate and numerical solutions can be found. As a result, we make numerical comparisons using the residual error displayed in [30] to highlight the accuracy of the approximate solutions obtained. Also, to show the effect of the CF-derivative to the FADEs, we compare the RK solutions for the integer-order ADEs and FADEs in the Hilbert space \(\mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\). The RKA results are provided tabularly and graphically using 2D graphs, which show a remarkable effect on the solution behavior depending on the fractional order in the time direction. All calculations and drawings were performed via Mathematica 12 software package. Anyhow, the residual function can be constructed as follows

Example 5.1

Consider the following CF-derivative nonlinear FADE of the first kind:

By applying the RK algorithm, taking \(t_{i} = \frac{i-1}{n-1}\), \(i = 1,\ldots,n\), and constructing the residual function \(\operatorname{Res}(t)\) we compare the approximate solutions and the residual errors for \(\alpha \in \{0.85,0.9,0.95\}\) when \(n=30\), and the obtained results are included in Table 1. To show the accuracy of the RK algorithm for solving this example graphically, the approximate solutions for several orders of the CF-derivative are shown in Fig. 1 for \(t \in [0,1]\), \(n=30\), and \(\alpha \in \{0.8,0.85,0.9,0.95, 1\}\). Table 2 shows the residual errors for \(\alpha =1\) and \(n=30, 25\), and 20, where the residual error function is

From Table 2 we can see that as n increases, the residual error function \(\operatorname{Res}(t)\) decreases, which confirms the convergence of the proposed algorithm.

Fractional level curves of CF-derivative of Example 5.1: blue \(\alpha = 0.8\), yellow \(\alpha = 0.85\), green \(\alpha = 0.9\), red \(\alpha = 0.95\), and black \(\alpha =1\)

Example 5.2

Consider the following CF-derivative nonlinear FADE of the first kind:

To apply the proposed algorithm, take \(t_{i} = \frac{i-1}{n-1}\), \(i = 1,\ldots ,n\), and construct the residual function

Anyhow, the obtained numerical values of the approximate solutions are summarized in the form of tables and graphs as follows: The RK solutions and residual errors are shown in Table 3 for \(\alpha \in \{0.85,0.9,0.95, 1\}\) and \(n=30\). Table 4 shows the residual errors of \(\omega _{n}(t)\) for different values of n and \(\alpha =1\). Meanwhile, the fractional level curves of the CF-derivative of the approximate solutions are presented in 2D graphs in Fig. 2 for \(\alpha \in \{0.8,0.85,0.9,0.95,1\}\) and \(n=30\). These results show that the behavior of solutions for various fractional levels is in harmony with each other.

Fractional level curves of CF-derivative of Example 5.2: blue \(\alpha = 0.8\), yellow \(\alpha = 0.85\), green \(\alpha = 0.9\), red \(\alpha = 0.95\), and black \(\alpha =1\)

Example 5.3

Consider the following CF-derivative nonlinear FADE of second kind:

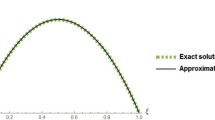

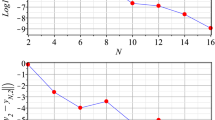

The exact solution of the FADE (5.4) at \(\alpha =1\) is \(e^{-t}\) [27]. By applying the RK algorithm the absolute and relative errors over the interval \([0,1]\) for \(\alpha =1\) and \(n=30\) are provided in Table 5 with step size 0.1. Figure 3 illustrates the curve behavior of the exact and RK solutions for \(\alpha =1\) and \(n=30\), whereas Fig. 4 shows the maximum absolute error during the interval \([0,1]\) for \(\alpha =1\).

Absolute error of Example 5.3 when \(\alpha =1\) and \(n=30\)

Exact \(\omega (t)\) (red) and RK solution \(\omega _{30}(t)\) (dashed) for Example 5.3 at \(\alpha =1\)

On the other hand, numerical comparison of the approximate solutions between the CF and Caputo fractional derivative is presented in Table 6 for different fractional values \(\alpha \in \{0.8,0.85,0.9,0.95\}\) of Example 5.3 when \(n=30\). Figure 5 illustrates the behavior of the fractional level curves of the RKM solutions within the CF-derivative and the Caputo derivative for several orders α and \(n=30\). Consequently, the acquired results show the great convergence of computations with preference for the novel CF-derivative due to the time spent on CPU speed compared to the simulation formulas using the Caputo derivative.

Fractional level curves of approximate solution of Example 5.3: blue \(\alpha = 0.8\), yellow \(\alpha = 0.85\), green \(\alpha = 0.9\), red \(\alpha = 0.95\), and black line \(\alpha =1\)

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we implemented the reproducing kernel method for a nonlinear fractional Abel differential equation involving the CF-fractional derivative with an exponential kernel. The reproducing kernel functions have been employed to generate the basis functions that satisfied the specified initial condition. In Hilbert spaces a numerical algorithm for solving FADE of both kinds has been developed utilizing the related RK theory. The stability and convergence were also discussed, whereas the RK solution of the FADE (4.1) was proved to be stable in \(\mathcal{H}^{2}[a,b]\). The results obtained from the numerical experiments indicate that the proposed method is simple, robust, and impressive. Moreover, the presented method has the ability to handle nonlinear evolution models. The numeric calculations were provided via Mathematica 12—Wolfram.

Availability of data and materials

Contact the authors for data requests.

References

Miller, K.S., Ross, B.: An Introduction to the Fractional Calculus and Fractional Differential Equations. Wiley, New York (1993)

Kilbas, A.A., Srivastava, H.M., Trujillo, J.J.: Theory and Applications of Fractional Differential Equations. North-Holland Mathematics Studies, vol. 204. Elsevier, Amsterdam (2006)

Al-Smadi, M., Abu Arqub, O., Hadid, S.: An attractive analytical technique for coupled system of fractional partial differential equations in shallow water waves with conformable derivative. Commun. Theor. Phys. 72(8), 085001 (2020)

Al-Smadi, M., Abu Arqub, O., Hadid, S.: Approximate solutions of nonlinear fractional Kundu–Eckhaus and coupled fractional massive Thirring equations emerging in quantum field theory using conformable residual power series method. Phys. Scr. 95(10), 105205 (2020)

Al-Smadi, M., Abu Arqub, O., Momani, S.: Numerical computations of coupled fractional resonant Schrödinger equations arising in quantum mechanics under conformable fractional derivative sense. Phys. Scr. 95(7), 075218 (2020)

Alabedalhadi, M., Al-Smadi, M., Al-Omari, S., Baleanu, D., Momani, S.: Structure of optical soliton solution for nonlinear resonant space-time Schrödinger equation in conformable sense with full nonlinearity term. Phys. Scr. 95(10), 105215 (2020)

Atangana, A., Baleanu, D., Alsaedi, A.: New properties of conformable derivative. Open Math. 13, 889–898 (2015)

Al-Smadi, M., Freihat, A., Khalil, H., Momani, S., Khan, R.A.: Numerical multistep approach for solving fractional partial differential equations. Int. J. Comput. Methods 14, 1750029 (2017)

Baleanu, D., Fernandez, A.: On some new properties of fractional derivatives with Mittag-Leffler kernel. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 59(9), 444–462 (2018)

Caputo, M., Fabrizio, M.: A new definition of fractional derivative without singular kernel. Prog. Fract. Differ. Appl. 1(2), 73–85 (2015)

Losada, J., Nieto, J.J.: Properties of a new fractional derivative without singular kernel. Prog. Fract. Differ. Appl. 1(2), 87–92 (2015)

Abdeljawad, T., Baleanu, D.: On fractional derivatives with exponential kernel and their discrete versions. Rep. Math. Phys. 80, 11–27 (2017)

Atangana, A., Baleanu, D.: New fractional derivatives with non-local and non-singular kernel: theory and application to heat transfer model. Therm. Sci. 20, 763–769 (2016)

Djeddi, N., Hasan, S., Al-Smadi, M., Momani, S.: Modified analytical approach for generalized quadratic and cubic logistic models with Caputo–Fabrizio fractional derivative. Alex. Eng. J. 59(6), 5111–5122 (2020)

Al-Smadi, M., Abu Arqub, O., Zeidan, D.: Fuzzy fractional differential equations under the Mittag-Leffler kernel differential operator of the ABC approach: theorems and applications. Chaos Solitons Fractals 146, 110891 (2021)

Aydogan, M.S., Baleanu, D., Mousalou, A., Rezapour, S.: On high order fractional integro-differential equations including the Caputo–Fabrizio derivative. Bound. Value Probl. 2018, 90 (2018)

Hasan, S., El-Ajou, A., Hadid, S., Al-Smadi, M., Momani, S.: Atangana–Baleanu fractional framework of reproducing kernel technique in solving fractional population dynamics system. Chaos Solitons Fractals 133, 109624 (2020)

Hasan, S., Al-Smadi, M., El-Ajou, A., Momani, S., Hadid, S., Al-Zhour, Z.: Numerical approach in the Hilbert space to solve a fuzzy Atangana–Baleanu fractional hybrid system. Chaos Solitons Fractals 143, 110506 (2021)

Bülbül, B., Sezer, M.: A numerical approach for solving generalized Abel-type nonlinear differential equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 262, 169–177 (2015)

Li, T., Pintus, N., Viglialoro, G.: Properties of solutions to porous medium problems with different sources and boundary conditions. Z. Angew. Math. Phys. 70(3), 86 (2019)

Anedda, C., Cuccu, F., Frassu, S.: Steiner symmetry in the minimization of the first eigenvalue of a fractional eigenvalue problem with indefinite weight. Can. J. Math., 1–23 (2020). https://doi.org/10.4153/S0008414X20000267

Infusino, M., Kina, T.: The full moment problem on subsets of probabilities and point configurations. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 483(1), 123551 (2020)

Li, T., Viglialoro, G.: Boundedness for a nonlocal reaction chemotaxis model even in the attraction dominated regime. Differ. Integral Equ. 34(5/6), 315–336 (2021)

Viglialoro, G., González, Á., Murcia, J.: A mixed finite-element finite-difference method to solve the equilibrium equations of a prestressed membrane having boundary cables. Int. J. Comput. Math. 94(5), 933–945 (2017)

Harko, T., Mak, M.K.: Exact travelling wave solutions of non-linear reaction–convection–diffusion equations—an Abel equation based approach. J. Math. Phys. 56, 111501 (2015)

Jafari, H., Sayevand, K., Tajadodi, H., Baleanu, D.: Homotopy analysis method for solving Abel differential equation of fractional order. Cent. Eur. J. Phys. 11, 1523–1527 (2013)

Rigi, F., Tajadodi, H.: Numerical approach of fractional Abel differential equation by Genocchi polynomials. Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math. 5, 134 (2019)

Xu, Y., He, Z.: The short memory principle for solving Abel differential equation of fractional order. Comput. Math. Appl. 62, 4796–4805 (2011)

Parand, K., Nikarya, M.: New numerical method based on generalized Bessel function to solve nonlinear Abel fractional differential equation of the first kind. Nonlinear Eng. 8, 438–448 (2019)

Parand, K., Nikarya, M.: Application of Bessel functions for solving differential and integro-differential equations of the fractional order. Appl. Math. Model. 38, 4137–4147 (2014)

Yamaleev, R.M., Russia, D.: Solutions of Riccati–Abel equation in terms of third order trigonometric functions. Indian J. Pure Appl. Math. 45(2), 165–184 (2014)

Mak, M.K., Harko, T.: New method for generating general solution of Abel differential equation. Comput. Math. Appl. 43, 91–94 (2002)

Mukherjee, S., Goswami, D., Roy, B.: Solution of higher-order Abel equations by differential transform method. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C 23(9), 1250056 (2012)

Al-Smadi, M., Abu Arqub, O., El-Ajou, A.: A numerical iterative method for solving systems of first-order periodic boundary value problems. J. Appl. Math. 2014, 135465 (2014)

Al-Smadi, M., Abu Arqub, O.: Computational algorithm for solving Fredholm time-fractional partial integrodifferential equations of Dirichlet functions type with error estimates. Appl. Math. Comput. 342, 280–294 (2019)

Geng, F.Z.: Numerical methods for solving Schrödinger equations in complex reproducing kernel Hilbert spaces. Math. Sci. 14, 293–299 (2020)

Altawallbeh, Z., Al-Smadi, M., Komashynska, I., Ateiwi, A.: Numerical solutions of fractional systems of two-point BVPs by using the iterative reproducing kernel algorithm. Ukr. Math. J. 70(5), 687–701 (2018)

Al-Smadi, M.: Simplified iterative reproducing kernel method for handling time-fractional BVPs with error estimation. Ain Shams Eng. J. 9(4), 2517–2525 (2018)

Al-Smadi, M., Abu Arqub, O., Momani, S.: A computational method for two-point boundary value problems of fourth-order mixed integrodifferential equations. Math. Probl. Eng. 2013, 832074 (2013)

Al-Smadi, M., Freihat, A., Abu Hammad, M., Momani, S., Abu Arqub, O.: Analytical approximations of partial differential equations of fractional order with multistep approach. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 13(11), 7793–7801 (2016)

Al-Smadi, M.: Reliable numerical algorithm for handling fuzzy integral equations of second kind in Hilbert spaces. Filomat 33(2), 583–597 (2019)

Al-Smadi, M., Abu Arqub, O., Shawagfeh, N., Momani, S.: Numerical investigations for systems of second-order periodic boundary value problems using reproducing kernel method. Appl. Math. Comput. 291, 137–148 (2016)

Gumah, G., Naser, M., Al-Smadi, M., Al-Omari, S.K.Q., Baleanu, D.: Numerical solutions of hybrid fuzzy differential equations in a Hilbert space. Appl. Numer. Math. 151, 402–412 (2020)

Al-Smadi, M., Abu Arqub, O., Gaith, M.: Numerical simulation of telegraph and Cattaneo fractional-type models using adaptive reproducing kernel framework. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/mma.6998

Gumah, G., Moaddy, K., Al-Smadi, M., Hashim, I.: Solutions to uncertain Volterra integral equations by fitted reproducing kernel Hilbert space method. J. Funct. Spaces 2016, 2920463 (2016)

Geng, F., Qian, S.P.: A new reproducing kernel method for linear non local boundary value problems. Appl. Math. Comput. 248, 421–425 (2014)

Li, X., Wu, B.: Error estimation for the reproducing kernel method to solve linear boundary value problems. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 243, 10–15 (2013)

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank their friends for their support.

Funding

No funding sources to be declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors contributed equally and significantly in writing this paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Smadi, M., Djeddi, N., Momani, S. et al. An attractive numerical algorithm for solving nonlinear Caputo–Fabrizio fractional Abel differential equation in a Hilbert space. Adv Differ Equ 2021, 271 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-021-03428-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-021-03428-3