Abstract

Ebola virus disease (EVD) is a severe infection with an extremely high fatality rate spread through direct and indirect contacts. Recently, an outbreak of EVD in West Africa brought public attention to this deadly disease. We study the spread of EVD through a two-patch model. We determine the basic reproduction number, the disease-free equilibrium, two boundary equilibria and the endemic equilibrium when the disease persists in the two sub-populations for specific conditions. Further, we introduce time-dependent controls into our proposed model. We analyse the optimal control problem where the control system is a mathematical model for EVD that incorporates educational campaigns. The control functions represent educational campaigns in their respective patches, with one patch having more effective controls than the other. We aim to study how these control measures would be implemented for a certain time period, in order to reduce or eliminate EVD in the respective communities, while minimising the intervention implementation costs. Numerical simulations results are provided to illustrate the dynamics of the disease in the presence of controls.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Ebola virus disease (EVD) is a highly infectious disease caused by the Ebola virus from the family of Filoviridae viruses. The Ebola virus is believed to be found in mammals of the family of Pteropodidae (fruit bats) [1]. It is a virus having a filamentous, enveloped and a non-segmented negative sense with the entry of the virus to living cells facilitated by its enveloped glycoprotein [2, 3]. The current Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in West Africa is now the largest documented [4]. Ebola originated in Zaire and Sudan in 1976 with several strains known at present. The outbreak in 2015 affected mainly Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone (West Africa) causing more than 28 000 infections and over 11 100 deaths by December 2015 [5]. The epidemic continued increasing due to socio-economic disadvantage and shortages in the health systems of the three mainly affected countries (Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone) [4, 6]. Currently, in 2018 the EVD has resurfaced in the Province of Kivu in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). In Kivu, there is a military conflict and there are thousands of displaced refugees [7, 8]. The affected area has a lot of trade among the different communities within, and this leads to massive inter-community movements. Due to the running battles in the Province of Kivu, health care workers and those who might be able to assist in the fight against EVD find it difficult to reach all the communities [9]. Thus, the respective communities in the affected areas of the DRC have greatly varying intervention strategies and some are not perfect. In the Province of Kivu, rebels are against the presence of the health caregivers and UN peacekeepers, hence EVD might be difficult to curtail in the Democratic Republic of Congo [9, 10].

Partially eaten fruits and pulp dropped by the bats are then eaten by the land mammals such as monkeys, apes, baboons and gorillas. This chain of events then forms a possible transmission of the Ebola virus from bats to other mammals [1]. Infection with humans can occur through direct contact with blood or body fluids (like saliva, sweat, faeces, breast milk and semen), objects like needles and syringes that have been contaminated with the virus and infected fruit bats or other mammals [11, 12]. The survival of the virus in the environment, due to poor hygienic and sanitary conditions, is probably another source of Ebola infection in many places in Africa [13, 14]. In Africa, and particularly in the regions that were affected by Ebola outbreaks, people who live close to the rain-forests, hunt bats and monkeys and harvest forest fruits for food [15, 16]. Africans are sincere to the point that even a transmittable disease would not stop them from showing compassion for their relatives at home, caressing them and shaking hands, as this is part of their beliefs and customs. In addition, in the course of the funerals, they bath and clothe up their lifeless relatives [17]. They even share without appropriate washing the clothes of their lifeless relatives. Thus, the virus can be spread directly or indirectly.

Without effective vaccines and treatment, educational campaigns may be implemented as a countermeasure. One of the primary reasons for the spread of the virus is the poorly functioning health systems in the part of Africa where the disease occurs. Other reasons are illiteracy, poverty and lack of enough information on the mode of spread of the virus [18]. People who care for infected individuals have an increased risk of transmission. Recommended measures when caring for the infected include medical isolation through proper use of gloves, masks, gowns, boots and goggles as well as sterilisation of equipment and surfaces. Certain control strategies are employed when local, regional and international associates are informed of an establishment of a possible Ebola epidemic. The controls among them are and not restricted to the following; assessment of the worldwide health risk, establishment of social mobilisation and health education curriculum to listen and address public concerns. The application of such control procedures leads to the curtailing of the current EVD epidemic of 2014, 2015. Due to the weaker economies of the affected countries, it was a limiting factor in the fight against EVD [17]. Resource allocation needs to be optimal and the control strategies need to be implemented in such a way as to derive maximum benefits. It is worth noting that optimal control is best described by mathematical modelling. Optimal control theory has proven to be a successful tool in understanding ways to curtail the spread of infectious diseases by devising the optimal disease intervention strategies. The method consists of minimising the cost of infection or the cost of implementing the control, or both. For more on optimal control theory in epidemiology, we refer the reader to Malik and Sharomi, 2015 [19].

Mathematical modelling remains a powerful tool in describing the dynamics of disease outbreaks and making predictions. It also enables us to estimate the long term effects of interventions, integrates evidence from different scientific disciplines and investigates how health-related practices evolve in complex systems. Statistical and biological studies have been applied in the study of the complexity of the Ebola virus life ecology [20, 21], and are worthy of attention. Some dynamic models have been proposed to study and to try to understand the dynamics of EVD [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Recently, Berge et al. [29] proposed a deterministic mathematical model for the transmission dynamics of EVD which involved a synergy between the epizootic phase, enzootic phase and the endemic phase. It included the direct and indirect modes of contamination, between and within the three different types of populations consisting of humans, animals and fruit bats. Work done by Berge et al. [29] was an extension of their previous work done in 2015 [26], in which a simple mathematical model was developed, which incorporated both the direct and the indirect Ebola virus transmission in such a way that there is a provision of Ebola viruses. Models have also been developed to try and understand various intervention strategies in trying to curtail the spread of EVD [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. The impact of vaccination and vaccines was investigated in [35, 36, 39, 40] and the issue of quarantining analysed in [35, 37] through mathematical models. Further, Berge et al. [31] developed a mathematical model to understand the impact of contact tracing as a control strategy of EVD. In recent times, optimal control problems have generated a lot of interest from researchers. Furthermore, various techniques and intervention strategies have been applied to study optimal control problems related to EVD [41,42,43,44,45,46]. In particular, Area et al. [44] proposed an EVD mathematical model with the vaccination of the susceptible population, with the aim of controlling the spread of the disease and analysis of two optimal control problems related to the transmission of EVD with vaccination. A deterministic SEIR type model with additional hospitalisation, quarantine and vaccination was developed and studied by Ahmad et al. [43], to understand the disease dynamics.

Although substantial work has been done on the study of EVD transmission dynamics, not much consideration of meta-population study has been done; see [47, 48]. The population is subdivided into several discrete patches which are supposed to be well mixed. Then, in each patch, the population is subdivided into compartments corresponding to different epidemic status. For more on meta-population patch models, see [49]. In this work, motivated by the usefulness of and the current investigation on modelling EVD, we intend to systematically investigate the modelling and analysis of a two-patch model for the transmission dynamics of EVD. We make use of the model studied by Berge et al. [26] which takes into account both, the direct and indirect modes of transmission. Thus, in our model, we distinguish two patches. We assume the susceptible and the recovered individuals are the only ones who migrate, hence the two sub-populations can vary. This is consistent with the fact that in African refugee camps refugees move very little between two camps and only persons that bring them help move within the camps. These limited migrations on the susceptible individuals have taken place in places such as the Democratic Republic of Congo [9, 10]. We also support our assumption that the majority of the infectious individuals do not migrate, due to their state of health. This can also be supported by the fact that in periods of epidemics, countries tighten people’s movements and their respective boarders through screening and detection. Both the people who are allowed to cross a border and those who move between two refugee camps/communities are assumed to be susceptible and recovered. A mathematical model describing the optimal control of an epidemic with educational campaigns have been discussed before [50], hence in our two-patch model, we introduce two time-dependent controls in educational campaigns, which have different effectiveness.

The paper is structured as follows. The EVD transmission model is formulated in Sect. 2 and the analytical results of the model are presented in Sect. 3. In Sect. 4 optimal control theory has been applied to the model formulated in Sect. 2. Simulation results and projection profiles of EVD are presented in Sect. 5. A summary and concluding remarks complete the paper.

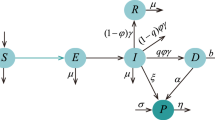

2 Model formulation

We consider a two-patch model for Ebola virus disease (EVD). The model consists of two sub-populations of a large one. The recruitment in each sub-population is only in the susceptible class, and the migration between the sub-populations is by the susceptible and recovered. Having the infectious class not migrating, we assume that infection does not take place during the migration process. Each human sub-population is divided into four classes: the susceptibles \(S_{i}(t)\), infectious \(I_{i}(t)\), recovered \(R_{i}(t)\) and deceased human individuals \(D_{i}(t)\). The Ebola virus in the environment is denoted by \(W_{i}(t)\). For all the parameters and compartmental classes, we will consider the case for \(i=1,2\), representing patch 1 and 2, respectively. The susceptible human population is replenished by constant recruitment at rate \(b_{i}\). Death for a reason that is not related to EVD is proportional to the population size and with a constant rate \(\mu _{i}\). The additional death due to disease affects only the class \(I_{i}(t)\), at a rate \(v_{i}\).

It has been shown that human individuals can be infected through the contaminated environment [51]. Thus, the Ebola virus is transmitted though both direct and indirect transmission. The susceptible individuals acquire the infection at rate \(\varLambda _{i}\) with

the form of incidence is bilinear. \(\beta _{I_{i}}I_{i} + \beta _{D_{i}}D _{i}\) is the direct infection from the infectious individuals and the dead bodies. \(\beta _{W_{i}}\) is the indirect infection from the Ebola virus in the environment to the susceptible individuals. \(\beta _{I _{i}}\) is the effective contact rate of the infectious individuals, \(\beta _{D_{i}}\) is the effective contact rate of the deceased individuals and \(\beta _{W_{i}}\) is the effective contact rate of the Ebola virus (in the environment).

Motivated by the fact that it has never been reported that an individual caught EVD for the second time, we assume that the infectious individuals recover at rate \(\phi _{i}\) attaining permanent disease-induced immunity. We assume that the Ebola virus finds its way into the environment only through the infectious and the deceased human individuals, which they shed into the environment especially through the urine and stool at rates \(\delta _{i}\) and \(\rho _{i}\), respectively. This assumption is supported by several references [52,53,54]. This happens in regions of poor sanitary facilities and/or in the regions where people do not observe appropriate hygiene practices. The Ebola virus in the environment decays and loses its infectiousness at a rate \(r_{i}\). The deceased human individuals lose their infectiousness through methods such as proper handling and burial at a rate \(\alpha _{i}\). The migration rates of the susceptible and the recovered individuals, between the two populations, are \(a_{i}\) and \(b_{i}\) for \(i=1,2\) respectively. This yields the following set of differential equations:

The total human population, the total deceased human individuals and the Ebola virus pathogens in the environment are given by \(N(t) = S_{1}(t) + I_{1}(t) + R_{1}(t) + S_{2}(t) + I_{2}(t) + R_{2}(t)\), \(D(t) = D_{1}(t) + D_{2}(t)\) and \(W(t) = W_{1}(t) + W_{2}(t)\), respectively.

Once \(S_{i}\), \(I_{i}\), \(D_{i}\), \(W_{i}\), \(i=1,2\) are obtained from Eqs. (2)1, (2)2, (2)4, (2)5, the functions \(R_{i}\), \(i=1,2\) are readily given by Eq. (2)3. Thus without loss of generality, we are led to the following reduced system:

2.1 Basic properties of the model

In this section, we study the basic properties of the solutions of system (3) which are essential in the proofs of stability.

Theorem 1

Let the initial data be \(S_{i}(0) >0\), \(I_{i}(0)>0\), \(D_{i}(0)>0\), \(W_{i}(0)>0\), \(i=1,2\). Then the solutions \(S_{i}(t)\), \(I_{i}(t)\), \(D_{i}(t)\), \(W_{i}(t)\) for system (3) are non-negative for all \(t >0\).

A complete proof for Theorem 1 has been outlined in Appendix 1.

Theorem 2

System (3) is a dynamical system on the biologically feasible compact set

where \(b = b_{1} + b_{2}\), \(\mu _{0} = \min (\mu _{1},\mu _{2})\), \(\overline{v} = \max (v_{1},v_{2})\), \(\overline{\delta } = \max (\delta _{1},\delta _{2})\), \(\overline{\rho } = \max (\rho_{1},\rho _{2})\), \(\overline{\alpha} = \max (\alpha _{1},\alpha _{2})\), \(\underline{\alpha} = \min (\alpha _{1},\alpha _{2})\), \(\underline{r}= \min (r_{1},r_{2})\).

A complete proof for Theorem 2 has been outlined in Appendix 2.

3 Analysis of the model

3.1 The disease-free equilibrium and basic reproduction number

The global behaviour for this model crucially depends on the basic reproduction number, that is, the average number of secondary cases produced by a single infective individual which is introduced into an entirely susceptible population. System (3) has an evident equilibrium \(\mathcal{E}^{0} = (S_{1}^{0},0,0,0,0,S_{2}^{0},0,0,0,0)\) when there is no disease, where

We calculate the basic reproduction number, \(\mathcal{R}_{0}\), using the next generation method approach developed in van den Driessche and Watmough [55]. Following [55], the non-negative matrix F and the non-singular matrix V for the new infection terms and the remaining transfer terms are respectively given at the disease-free equilibrium by

Then the reproduction number \(\mathcal{R}_{0}\) of system (3) is the spectral radius of the next generation matrix \(FV^{-1}\),

where \(\mathcal{R}_{i}\) (\(i=1,2\)) is the basic reproduction number of each sub-population i given by

Following the interpretation in [56], \(\mathcal{R}_{i}\) for patch i, for \(i=1,2\), is the sum of three infection contributions:

-

\(\mathcal{R}_{I_{i}}\) is the contribution of the infectious human \(I_{i}\).

-

\(\mathcal{R}_{D_{i}}\) is the contribution of the infected corpses \(D_{i}\).

-

\(\mathcal{R}_{W_{i}}\) is the contribution due to the environmental contamination by the virus \(W_{i}\).

Biologically \(\mathcal{R}_{1}\) and \(\mathcal{R}_{2}\) measure the average number of secondary infections generated by an Ebola virus in patch 1 and patch 2 respectively, when introduced in a disease-free population. The reproductive number \(\mathcal{R}_{0}\) controls the number of equilibria of system (3).

If \(\mathcal{R}_{0} \leq 1\), then the disease-free equilibrium \(\mathcal{E}^{0}\) is the only equilibrium in \(\mathcal{G}\). Using Theorem 2 in van den Driessche and Watmough (2002) [55], the following result is established.

Theorem 3

The disease-free equilibrium (DFE) \(\mathcal{E}^{0}\) of system (3) is locally asymptotically stable (LAS) if \(\mathcal{R} _{0} < 1\) and unstable otherwise.

We now utilise the approach of Lyapunov functions [57,58,59] in the analysis of the global asymptotic stability.

Theorem 4

If \(\mathcal{R}_{0} \leq 1\), the DFE is globally asymptotically stable (GAS) in \(\mathcal{G}\). If \(\mathcal{R}_{0} > 1\), the system is uniformly persistent.

Proof

Let \(\mathcal{Y}(t) = (I_{1},D_{1},W_{1},I_{2},D_{2},W_{2})\). Since

it follows that

where F and V are defined in (6). It is worth noting that F and \(V^{-1}\) are non-negative. By the Perron–Frobenius theorem [60], the non-negative matrix \(V^{-1}F\) has a non-negative left eigenvector \(u \geq 0\) with respect to \(\rho (V^{-1}F) = \rho (FV^{-1}) = \mathcal{R}_{0}\), that is, \(u^{T}V^{-1}F = \mathcal{R}_{0}u^{T}\). Motivated by [59], we consider the Lyapunov function

Differentiating \(\mathcal{L}\) along solutions of (3), we have

It can be easily verified that the largest invariant subset of \(\mathcal{G}\) where \(\dot{\mathcal{L}} = 0\) is the singleton \(\lbrace \mathcal{E}^{0} \rbrace \). Therefore, by LaSalle’s invariance principle [61], \(\mathcal{E}^{0}\) is globally asymptotically stable in \(\mathcal{G}\) when \(\mathcal{R}_{0} \leq 1\).

If \(\mathcal{R}_{0} > 1\), then, by continuity, \(\dot{\mathcal{L}} > 0\) in a neighbourhood of \(\mathcal{E}^{0}\) in the interior of \(\mathcal{G}\). Solutions in the interior of \(\mathcal{G}\) sufficiently close to \(\mathcal{E}^{0}\) move away from the DFE, implying that the DFE is unstable. This completes the proof. □

The result in Theorem 4 shows that \(\mathcal{R}_{0} = 1\) is a sharp threshold for disease dynamics: the disease will die out when \(\mathcal{R}_{0} \leq 1\), whereas the disease will persist when \(\mathcal{R}_{0} > 1\). We now investigate uniform persistence; we claim the following result.

Theorem 5

If \(\mathcal{R}_{0} > 1\), system (3) is uniformly persistent, namely, there exists a constant \(\zeta > 0\) such that

where ζ is independent of the initial data in \(\mathcal{G}\).

Proof

We prove that system (3) is uniformly persistent with respect to \((X_{0},\partial X_{0})\), where

By the form of (3), it is very easy to see that both X and \(X_{0}\) are positively invariant and \(\partial X_{0}\) is relatively closed in X. Furthermore, system (3) is point dissipative. Let

We now show that

It is worth noting that

so we only need to prove

Assume \(\lbrace (S_{i}(0),I_{i}(0),D_{i}(0),W_{i}(0)) \rbrace \in M _{\partial }\), for \(i=1,2\). It suffices to show that

Suppose not, then there exist an \(i_{0}\), \(i_{0}=2\) and \(t_{0} \geq 0\) such that

without loss of generality, assume

then we have

It follows that there is an \(\eta > 0\) such that \(W_{2}(t) > 0\), for \(t_{0} < t < t_{0} + \eta \). This means that

does not belong to \(\partial X_{0}\), \(i =1,2\) for \(t_{0} < t < t_{0} + \eta \), which contradicts the assumption that

Thus (15) holds.

It is worth noting that \(\mathcal{E}^{0}\) is globally stable for system (3). It is clear that there is only an equilibria \(\mathcal{E}^{0}\) in \(M_{\partial }\), by the aforementioned claim, it then follows that \(\mathcal{E}^{0}\) is an isolated invariant set in X, \(W^{S}(\mathcal{E}^{0}) \cap X_{0} = \emptyset \). Clearly, every orbit in \(M_{\partial }\) converges to \(\mathcal{E}^{0}\), \(\mathcal{E} ^{0}\) is acyclic in \(M_{\partial }\). Using Theorem 4.6 in Thieme [62], we conclude that system (3) in uniformly persistent with respect to \((X_{0},\partial X_{0})\).

By the result of [63,64,65], system (3) has an equilibrium \(\mathcal{E}^{*} = (\overline{S}_{i},\overline{I}_{i}, \overline{D}_{i},\overline{W}_{i}) \in X_{0}\), \(i=1,2\). We further claim that \(\overline{S}_{i} > 0\), \(i=1,2\). Suppose that \(\overline{S}_{i} = 0\), \(i=1,2\), from the second equation of (3), we can get \(\overline{I}_{i} = \overline{D}_{i} = \overline{W}_{i} = 0\), \(i=1,2\). It is a contradiction. Then \((\overline{S}_{i},\overline{I}_{i}, \overline{D}_{i},\overline{W}_{i}, i=1,2)\), is a component-wise positive equilibrium of system (3). The proof is complete. □

3.2 Existence of equilibria

System (3) has one disease-free equilibrium, \(\mathcal{E} ^{0} = (S_{1}^{0},0,0,0,S_{2}^{0},0,0,0)\) and three endemic equilibria of the forms \(\mathcal{E}^{*}_{1} = (S_{1}^{*},I_{1}^{*},D_{1}^{*},W _{1}^{*},S_{2}^{*},0,0,0)\), \(\mathcal{E}^{*}_{2} = (S_{1}^{**},0,0,0,S _{2}^{**},I_{1}^{**},D_{1}^{**},W_{1}^{**})\) and \(\mathcal{E}^{*} = ( \overline{S}_{1},\overline{I}_{1},\overline{D}_{1},\overline{W}_{1}, \overline{S}_{2},\overline{I}_{2},\overline{D}_{2},\overline{W}_{2})\), corresponding respectively to states where the disease persists in the first sub-population and dies out in the second sub-population, the disease persists in the second sub-population and disappears in the first sub-population, and when the disease persists in the two sub-populations.

3.2.1 The first boundary equilibrium

The patch-1 system is obtained by making \(I_{2} = D_{2} = W_{2} = 0\), and it is given by

Let \(\mathcal{E}^{*}_{1} = (S_{1}^{*},I_{1}^{*},D_{1}^{*},W_{1}^{*},S _{2}^{*},0,0,0)\) be the first boundary endemic equilibrium with \(I_{1},D_{1}, W_{1} > 0\). Then the endemic equilibrium \(\mathcal{E} ^{*}_{1}\) can be obtained by setting to zero the right hand side of Eqs. (21), giving

It is straightforward to prove that, when \(\mathcal{R}_{1} > 1\) and \(\mathcal{R}_{2} \leq 1\), system (3) has exactly one non-trivial boundary endemic equilibrium \(\mathcal{E}^{*}_{1} = (S _{1}^{*},I_{1}^{*},D_{1}^{*},W_{1}^{*},S_{2}^{*},0,0,0)\) where \(S_{1} ^{*}\), \(I_{1}^{*}\), \(D_{1}^{*}\), \(W_{1}^{*}\), \(S_{2}^{*}\) are given by

We now present the local stability of \(\mathcal{E}^{*}_{1}\) when the reproduction number is close to 1. We make use of the centre manifold theory [66], but we first present the following lemma.

Lemma 1

Consider the following general system of ordinary differential equations with parameter ϕ:

where 0 is an equilibrium of the system, that is, \(f(0,\phi )=0 \) ∀ϕ, and assume:

A1) \(A=D_{x}f(0,0)= ( \frac{\partial f_{i}}{\partial x_{j}}(0,0) )\) is the linearisation of system (24) around the equilibrium 0 and ϕ evaluated at 0. Zero is a simple eigenvalue of A and other eigenvalues of A have negative real parts

A2) Matrix A has the right eigenvector u and a left eigenvector v corresponding to the zero eigenvalue. Let \(f_{k}\) be the kth component of f and

The local dynamics of (24) around zero are totally governed by a and b.

-

i.

\(a>0\), \(b>0\). When \(\phi < 0\) with \(\vert \phi \vert \ll 1\), and there exists a positive unstable equilibrium, when \(0 < \phi \ll 1\), 0 is unstable and there exists a negative and locally asymptotically stable equilibrium.

-

ii.

\(a<0\), \(b<0\). When \(\phi <0\) with \(\vert \phi \vert \ll 1\), 0 unstable; when \(0< \phi \ll 1\), 0 is locally asymptotically stable, and there exists a positive unstable equilibrium.

-

iii.

\(a>0\), \(b<0\). When \(\phi <0\) with \(\vert \phi \vert \ll 1\), 0 is unstable, and there exists a locally asymptotically stable negative equilibrium; when \(0 < \phi \ll 1\), 0 is stable, and a positive unstable equilibrium appears.

-

iv.

\(a<0\), \(b>0\). When ϕ changes from negative to positive, 0 changes its stability from stable to unstable. Corresponding a negative unstable equilibrium becomes positive and locally asymptotically stable.

Theorem 6

The unique patch 1-only boundary equilibrium, \(\mathcal{E}^{*}_{1}\), of system (3), is locally asymptotically stable when \(\mathcal{R}_{1} > 1\) but only if \(\mathcal{R}_{1}\) is close to 1.

The proof of Theorem 6 is outlined in Appendix 3.

3.2.2 The second boundary equilibrium

Let \(\mathcal{E}^{**}_{2} = (S_{1}^{**},0,0,0,S_{2}^{**},I_{2}^{**},D _{2}^{**},W_{2}^{**})\) be the second boundary endemic equilibrium with \(I_{2},D_{2},W_{2} \neq 0\). Then the endemic equilibrium \(\mathcal{E} ^{**}_{2}\) (steady state with \(I_{2},D_{2},W_{2} > 0\)) can be obtained by setting the right hand side of equations in system (3) to zero, that is,

It is straightforward to prove that, when \(\mathcal{R}_{2} > 1\) and \(\mathcal{R}_{1} \leq 1\), system (3) has exactly one non-trivial boundary endemic equilibrium \(\mathcal{E}^{**}_{2} = (S _{1}^{**},0,0,0,S_{2}^{**},I_{2}^{**},D_{2}^{**},W_{2}^{**})\) where \(S_{1}^{**}\), \(S_{2}^{**}\), \(I_{2}^{**}\), \(D_{2}^{**}\), \(W_{2}^{**}\) are given by

Theorem 7

The unique patch 2-only boundary equilibrium, \(\mathcal{E}^{*}_{2}\), of system (3), is locally asymptotically stable when \(\mathcal{R}_{2} > 1\) but only if \(\mathcal{R}_{2}\) is close to 1.

Proof

The proof for Theorem 7 follows the same procedure as outlined in Sect. 3.2.1 on the proof of the stability of patch 1-only boundary equilibrium, and the bifurcation parameter is computed by setting \(\mathcal{R}_{2} = 1\). □

3.2.3 The interior endemic equilibrium

\(\mathcal{E}^{*} = (\overline{S}_{1},\overline{I}_{1},\overline{D} _{1},\overline{W}_{1},\overline{S}_{2},\overline{I}_{2},\overline{D} _{2},\overline{W}_{2})\) be the interior endemic equilibrium when both infectious of the two sub-populations co-exist, like, \(I_{i} \neq 0\), \(D _{i} \neq 0\), \(W_{i} \neq 0\), \(i=1,2\). To find this endemic equilibrium, we equate system (3) to zero and rewrite it as follows:

Solutions of Eqs. (28) are defined by

where

Note that, when \(\mathcal{R}_{1}^{\star } > 1\) and \(\mathcal{R}_{2} ^{\star } > 1\), one has \(\mathcal{R}_{1} > 1\) and \(\mathcal{R}_{2} > 1\). Then system (3) has a non-trivial interior endemic equilibrium \(\mathcal{E}^{*} = (\overline{S}_{1},\overline{I}_{1},\overline{D} _{1},\overline{W}_{1},\overline{S}_{2},\overline{I}_{2},\overline{D} _{2},\overline{W}_{2})\) when \(\mathcal{R}_{1}^{\star } > 1\) and \(\mathcal{R}_{2}^{\star } > 1\).

We now investigate the local stability of the interior endemic equilibrium (29), and we shall make use of Lemma 1. We claim the following result.

Theorem 8

The unique interior equilibrium, \(\mathcal{E}^{*}\), of system (3), is locally asymptotically stable when \(\mathcal{R}_{0} > 1\) but only if the corresponding reproduction number is close to 1.

The proof of Theorem 8 is outlined in Appendix 4.

The existence of the endemic equilibrium of system (3) is summarised in the following theorem.

Theorem 9

System (3) has:

-

1.

A boundary endemic equilibrium of the form \(\mathcal{E}^{*}_{1} = (S _{1}^{*},I_{1}^{*},D_{1}^{*},W_{1}^{*},S_{2}^{*},0,0,0)\) whenever \(\mathcal{R}_{1} > 1\) and \(\mathcal{R}_{2} \leq 1\). This means that the disease is endemic in the first sub-population and dies out in the second population.

-

2.

A boundary endemic equilibrium of the form \(\mathcal{E}^{**}_{2} = (S _{1}^{**},0,0,0,S_{2}^{**},I_{2}^{**},D_{2}^{**},W_{2}^{**})\) whenever \(\mathcal{R}_{1} \leq 1\) and \(\mathcal{R}_{2} > 1\). This means that the disease is endemic in the second sub-population and dies out in the first population.

-

3.

An interior endemic equilibrium of the form \(\mathcal{E}^{*} = ( \overline{S}_{1},\overline{I}_{1},\overline{D}_{1},\overline{W}_{1}, \overline{S}_{2},\overline{I}_{2},\overline{D}_{2},\overline{W}_{2})\) whenever \(\mathcal{R}_{1} > 1\) and \(\mathcal{R}_{2} > 1\) which corresponds to the case when the disease persists in the two sub-populations.

4 Optimal control in educational campaigns

In this section, an optimal control problem is formulated by incorporating two intervention strategies into our basic model (3). Optimal control has been applied in the study of infectious diseases such as in [67,68,69]. Stopping the EVD transmission chain is still the main strategy to limit the spread of the disease. This can be achieved through educational campaigns that encourage behavioural changes like safe burial practices, self-isolation and proper hygiene [70]. To include educational campaigns into patch 1 and patch 2 as controls, \(u_{1}\) and \(u_{2}\) respectively, we extend system (3). The controlling effort \(u_{1}\) represents a time-dependent control in educational campaigns with respect to patch 1 and \(u_{2}\) representing a time-dependent control in educational campaigns with respect to patch 2. Educational campaigns, in this case, are aimed at encouraging the uninfected to have some protective behaviours. We assume that \(u_{1} > u_{2}\) since some neighbouring countries or communities might have lesser efforts compared to their neighbours in terms of control efforts. The extended model is given by

A successful control strategy is one that reduces the number of individuals infected with Ebola while minimising the costs associated with these efforts. Thus, our goal is to find a pair of controls \((u_{1}^{*},u_{2}^{*})\) that minimise the number of infected individuals and the cost of educational campaigns. Our objective functional is therefore formulated as

subject to the constraints given by (31) and where \(A_{1}\), \(A_{2}\), \(B_{1}\), \(B_{2}\) are positive balancing coefficients transferring integrals into monetary quantity over a finite period of time T weeks. The first two terms in (32) with coefficients \(A_{1}\) and \(A_{2}\) represent the weights of the individuals \(I_{1}\) and \(I_{2}\), respectively. The coefficients \(B_{1}\) and \(B_{2}\) represent the cost associated with the efforts in educational campaigns for patch 1 and 2, respectively. We seek the pair \((u_{1}^{*},u_{2}^{*}) \in \mathcal{U} \) such that

subject to the state system given by (31), where

is the control set. Next, we derive the optimality system.

4.1 The optimality system

Using the Pontryagin maximum principle [71], we now derive the necessary conditions that an optimal control and corresponding states must satisfy. This principle converts (31)–(33) into a problem of minimising pointwise a Hamiltonian \(\mathcal{H}\), with respect to \((u_{1}(t),u_{2}(t))\):

where \(\lambda _{i}\), \(i=1,2,\ldots,10\). are the adjoint variables. In the following theorem, we present the adjoint system and control characterisation.

Theorem 10

Given an optimal control \((u_{1}^{*},u_{2}^{*})\) and corresponding state solutions \(S_{i}\), \(I_{i}\), \(R_{i}\), \(D_{i}\), \(W_{i}\) of the corresponding state system (31) that minimises \(\mathcal{J}(u_{1},u_{2})\) over \(\mathcal{U}\), there exist adjoint variables (functions), \(\lambda _{i}(t)\), for \(i = 1,2,\ldots,10\), satisfying

with terminal conditions

Furthermore, the optimal controls \(u_{1}^{*}\) and \(u_{2}^{*}\) are represented by

Proof

The existence of optimal control follows from Corollary 4.1 of [72] since the integrand of \(\mathcal{J}\) is a convex function of \((u_{1},u_{2})\) and the state system satisfies the Lipshitz property with respect to the state variables. The following can be derived from the Pontryagin maximum principle [71]:

with \(\lambda _{i}(T) = 0\) for \(i=1,2,\ldots,10\) evaluated at the optimal controls and corresponding states, which results in the adjoint system (34). The Hamiltonian \(\mathcal{H}\) is minimised with respect to the controls at the optimal controls, so we differentiate \(\mathcal{H}\) with respect to \(u_{1}\) and \(u_{2}\) on the set \(\mathcal{U}\), respectively, giving the following optimality conditions:

Hence, we obtain

Taking into account the bounds on the controls, we obtain the desired characterisations. □

5 Numerical simulations

In this section, we now provide some numerical simulations. The existence of an optimal control is provided and the behaviour of the optimality system made of 10 ordinary differential equations is evaluated through numerical simulations done with Matlab. The optimality system is solved using an iterative method with the Runge–Kutta fourth order scheme. Starting with a guess for the adjoint variables, the state equations are solved forward in time. Then these state values are used to solve the adjoint equations backward in time, and the iterations continue until convergence.

To illustrate the results of the foregoing analysis, we have simulated system (3) using the parameters in Table 1. Parameters in Table 1 are taken from the recent works on the West African Ebola outbreaks. We then assume some of the parameters in the realistic range for illustrative purposes. We are using the same table of parameters for both patches. Among the estimated parameters, are the balancing coefficients which have been arbitrarily chosen for illustration purposes. These weight parameters determine the importance of variables in the objective functional [73]. Thus \(A_{1} =100\), \(A_{2} = 100\), \(B_{1} = B_{2} = 90\).

We first consider a scenario where we have net migration on \(a_{2}\), thus, \(a_{2} > a_{1}\) implying that we have \(\mathcal{R}_{1} > \mathcal{R}_{2} > 1\). We take \(a_{1} = 0.03\), \(a_{2} = 0.3\) and we assume that all other parameters take the same values for the two patches (see Table 1).

Figures 1\((a)\) and 1\((b)\) generally show that the controls have an impact on the control of EVD. Figure 1\((a)\) shows that the controls are highly effective in patch 1 since in the presence of the control the infected population is very low for the whole period under study. Figure 1\((b)\) depicts that the controls are effective only after 9 weeks. Figure 1\((c)\) and 1\((d)\) represents the controls \(u_{1}\) and \(u_{2}\) respectively. Both controls are at the upper bound for the whole period under study, 32 weeks. Thus under the given scenario, \(a_{2} > a_{1}\), both controls are feasible and effective for the whole period under study, hence more effort should be devoted to both controls in implementation.

We now consider a scenario where we have 0 net migration, thus \(a_{2} = a_{1}\), implying that we have \(\mathcal{R}_{1} = \mathcal{R} _{2} > 1\). We take \(a_{1} = 0.165\), \(a_{2} = 0.165\) and we assume that all other parameters take the same values for the two patches (see Table 1).

Figure 2\((a)\) and 2\((b)\) shows that the controls are effective in the reduction of EVD. Figure 2\((a)\) shows that the control \(u_{1}\) becomes effective after 14 weeks and Fig. 2\((a)\) shows that control \(u_{2}\) becomes effective after 2 weeks. It is worth noting that Fig. 2\((a)\) and 2\((b)\) shows that the controls are significant to a certain extent in the reduction of EVD. Figure 2\((c)\) and 2\((d)\) shows that the controls may not be sustainable for certain time intervals. In Fig. 2\((c)\) the control \(u_{1}\) is at the lower bound for 14 weeks. Thus, the control \(u_{1}\) is initiated after 14 weeks under this scenario. Control \(u_{2}\) starts at the upper bound and stays at the upper bound for the rest of the period under study. In this scenario, \(a_{2} = a_{1}\), more effort should be devoted to control \(u_{2}\). It is worth noting that control \(u_{2}\) is the less efficient one, hence devoting more effort to control \(u_{2}\) in controlling EVD might not be ideal.

Lastly, we consider a scenario where we have a net migration in \(a_{1}\), thus \(a_{1} > a_{2}\), implying that we have \(\mathcal{R}_{2} > \mathcal{R}_{1} > 1\). We take \(a_{1} = 0.3\), \(a_{2} = 0.03\) and we assume that all other parameters take the same values for the two patches (see Table 1).

Figures 3\((a)\) and 3\((b)\) depict that the controls are only effective up to a certain extent. Figure 3\((a)\), shows that the controls are effective during the last 28 weeks of the whole of 32 weeks under study. Figure 3\((b)\) shows that the controls are only effective in the first 28 weeks only. Figure 3\((c)\) and 3\((d)\) also shows that the controls may not be sustainable for certain time intervals. Figure 3\((c)\) shows that the control \(u_{1}\) starts at the lower bound and is initiated after 26 weeks. Figure 3\((d)\) shows that control \(u_{2}\) is at the upper bound for the rest of the period under study. Under this scenario, \(a_{1} > a_{2}\), it is worth noting that more effort should be devoted to control \(u_{2}\). Under the given scenario control, \(u_{1}\), which is the most effective, it is not feasible.

6 Discussion

Several countries in West Africa, in particular, Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia experienced morbidity and mortality during the Ebola epidemic from 2013–2015. At the time of this epidemic there was no known vaccine or drug, so effective disease control required coordinated efforts that include both standard strategies, such as hospitalisation, as well as community efforts, such as safe burial practices, proper hygiene in hospitals, etc. Not only are such efforts difficult to implement in practice, but there is also added complexity with connectivity between populations that have different policies in place. These complexities may affect some communities, that is, neighbouring communities might have lesser efforts compared to their neighbours in terms of control strategies. Currently, starting in August 2018 EVD is terrorising North Kivu in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a place with high mobility among the traders from different communities [7, 8].

In this manuscript, we formulated and analysed a differential equation-based two-patch model, with the patches connected by migration. EVD features and dynamics within a population such as the infectious environment, deceased individuals and the infectious individuals are incorporated in both patches. The susceptible and recovered individuals are the only ones who migrate. The basic reproductive number, \(\mathcal{R}_{0}\), for the model has been computed. Our results show that \(\mathcal{R}_{0}\), can provide a sharp threshold for the disease dynamics when \(\mathcal{R}_{0} \leq 1\) the disease-free equilibrium is globally stable indicating that the disease would die out, but when \(\mathcal{R}_{0} > 1\) the disease persists. Subsequently, we have performed an optimal control study on this two-patch model to effectively design control strategies to control EVD. The control \(u_{1}\) represents educational campaigns in patch 1 and the control \(u_{2}\) represents educational campaigns in patch 2, with \(u_{1} > u _{2}\). We considered two communities with the same control strategy, which differ in their levels of efficacy. Our major aim is to assess the spread of the EVD epidemic within two communities connected by migration, with these communities employing the same control strategy which only differ in efficiency. The technical tool used to determine the optimal strategy is the Pontryagin maximum principle. Numerical simulations results show that the implementation of the optimal control has a huge impact on the reduction of the infected individuals in both patches, and that the outcome of the control from each patch may be different due to their different characteristics. We also realised that, given our controls \(u_{1} > u_{2}\), it is advisable to have \(a_{2} > a_{1}\), as in the net migration is into patch 1, so as to control EVD faster and with maximum effort for fewer resources. It is worth noting that for the scenario \(a_{2} > a_{1}\) we have \(\mathcal{R}_{1} > \mathcal{R}_{2} > 1\). Thus, in the case of an EVD epidemic, we can manage to move the people who are not infected from places that have inefficient intervention strategies to places with higher efficient intervention strategies, regardless of the relative magnitude of the respective reproduction numbers in both communities. Generally, the study finds that EVD can be controlled if optimal educational campaigns are implemented, although this might not be appropriate for certain time intervals.

However, just like any other model, we cannot say the model is complete, it can be extended to include the aspect of the refugees, rebels and health care workers, like the case in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

References

Leroy, E.M., Kumulungui, B., Pourrut, X., Rouquet, P., Hassanin, A., Yaba, P., Delicat, A., Paweska, J.T., Gonzalez, J.P., Swanepoel, R.: Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature 438, 575–576 (2015)

Takada, A., Robison, C., Goto, H., Sanchez, A., Murti, K.G., Whitt, M.A., et al.: A system for functional analysis of Ebola virus glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94(26), 14764–14769 (1997)

Wool-Lewis, R.J., Bates, P.: Characterization of Ebola virus entry by using pseudo typed viruses: identification of receptor-deficient cell lines. J. Virol. 72, 3155–3160 (1998)

Lough, S.: Lessons from Ebola bring WHO reforms. CMAJ, Can. Med. Assoc. J. 187(12), E377–E378 (2015)

WHO: Ebola response road-map situation report. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/Ebola/situation-reports/en/ (2015). Accessed 5 Feb 2015

Lewnard, J.A., Ndeffo Mbah, M.L., Alfaro-Murillo, J.A., Altice, F.L., Bawo, L., Nyenswah, T.G., et al.: Dynamics and control of Ebola virus transmission in Montserrado, Liberia: a mathematical modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 14(12), 1189–1195 (2014)

NPR.org: Ebola in a conflict zone. Retrieved 2 August 2018

Relief Web: Congo Ebola outbreak compounds already dire humanitarian crisis. Retrieved 3 August 2018

Reuters: Editorial, Reuters (2018-09-04). Rebels ambush South African peacekeepers in Congo Ebola zone. Retrieved 4 September 2018

VOA: Rebel attack in Congo Ebola zone kills at least 14 civilians. Retrieved 23 September 2018

Peters, C., Peters, J.: An introduction to Ebola: the virus and the disease. J. Infect. Dis. 179, 9–16 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1086/514322

CDC: CDC report to Ebola virus disease 2014. Technical report (2014)

Bibby, K., Casson, L.W., Stachler, E., Haas, C.N.: Ebola virus persistence in the environment: state of the knowledge and research needs. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2, 2–6 (2015)

Piercy, T.J., Smither, S.J., Steward, J.A., Eastaugh, L., Lever, M.S.: The survival of filoviruses in liquids, on solid substrates and in a dynamic aerosol. J. Appl. Microbiol. 109(5), 1531–1539 (2010)

Leroy, E.M., Rouquet, P., Formenty, P., Souquière, S., Kilbourne, A., Froment, J.M., Bermejo, M., Smit, S., Karesh, W., Swanepoel, R., Zaki, S.R., Rollin, P.E.: Multiple Ebola virus transmission events and rapid decline of central African wildlife. Science 303(5656), 387–390 (2006)

Leroy, E.M., Kumulungui, B., Pourrut, X., Rouquet, P., Hassanin, A., Yaba, P., Délicat, A., Paweska, J.T., Gonzalez, J.P., Swanepoel, R.: Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature 438, 575–576 (2005)

Butler, D.: Six challenges to stamping out Ebola. http://www.nature.com/ (2015)

Chan, M.: Ebola virus disease in West Africa—no early end to the outbreak. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 1183–1185 (2014)

Sharomi, O., Malik, T.: Optimal control in epidemiology. Ann. Oper. Res. 251(1–2), 55–71 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-015-1834-4

Groseth, A., Feldmann, H., Strong, J.E.: The ecology of Ebola virus. Trends Microbiol. 15, 408–416 (2007)

Judson, S.D., Fischer, R., Judson, A., Munster, V.J.: Ecological contexts of index cases and spillover events of different Ebola viruses. PLoS Pathog. 12(8), e1005780 (2016)

Area, I., Losada, J., Ndaïrou, F., Nieto, J.J., Tcheutia, D.D.: Mathematical modeling of 2014 Ebola outbreak. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 40, 6114–6122 (2017)

Area, I., Batarfi, H., Losada, J., Nieto, J.J., Shammakh, W., Torres, A.: On a fractional order Ebola epidemic model. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2015, 278 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-015-0613-5

Imran, M., Khan, A., Ansari, A., Shah, S.: Modeling transmission dynamics of Ebola virus disease. Int. J. Biomath. 10(4), 1750057 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1142/S1793524517500577

Ivorra, B., Ngom, D., Ramos, A.M.: A mathematical model to predict the risk of human diseases spread between countries-validation and application to the 2014–2015 Ebola virus disease epidemic. Bull. Math. Biol. 77(9), 1668–1704 (2015)

Berge, T., Lubuma, J.M.S., Moremedi, G.M., Morris, N., Kondera-Shava, R.: A simple mathematical model for Ebola in Africa. J. Biol. Dyn. 11(1), 42–74 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/17513758.2016.1229817

Chavez, C., Barley, K., Bichara, D., Chowell, D., Diaz Herrera, E., Espinoza, B., Moreno, V., Towers, S., Yong, K.E.: Modeling Ebola at the Mathematical and Theoretical Biology Institute (MTBI). Not. Am. Math. Soc. 63(4), 367–371 (2016)

Agusto, F.B.: Mathematical model of Ebola transmission dynamics with relapse and reinfection. Math. Biosci. 283, 48–59 (2017)

Berge, T., Bowong, S., Lubuma, J., Manyombe, M.L.M.: Modeling Ebola virus disease transmissions with reservoir in a complex virus life ecology. Math. Biosci. Eng. 15(1), 21–56 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3934/mbe.2018002

Funk, S., Camacho, A., Kucharski, A.J., Eggo, R.M., Edmunds, W.J.: Real-time forecasting of infectious disease dynamics with a stochastic semi-mechanistic model. Epidemics 22, 56–61 (2018)

Berge, T., Ouemba Tasse, A.J., Tenkam, H.M., Lubuma, J.: Mathematical modelling of contact tracing as a control strategy of Ebola virus disease. Int. J. Biomath. 11(7), 1850093 (2018)

Guo, Z., Xiao, D., Li, D., Wang, X., Wang, Y., Yan, T., Wang, Z.: Predicting and evaluating the epidemic trend of Ebola virus disease in the 2014–2015 outbreak and the effects of intervention measures. PLoS ONE 11(4), e0152438 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152438

Salem, D., Smith R.: A mathematical model of Ebola virus disease: using sensitivity analysis to determine effective intervention targets. In: SummerSim-SCSC 2016, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, July 24–27 2016. Society for Modelling & Simulation International (SCS) (2016)

Weitz, J.S., Dushoff, J.: Modeling post-death transmission of Ebola: challenges for inference and opportunities for control. Sci. Rep. 5, 8751 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08751

Tulu, T.W., Tian, B., Wu, Z.: Modeling the effect of quarantine and vaccination on Ebola disease. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2017, 178 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-017-1225-z

Berge, T., Chapwanya, M., Lubuma, J., Terefe, Y.A.: A mathematical model for Ebola epidemic with self protection measures. J. Biol. Syst. 26(1), 107–131 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218339018500067

Denes, A., Gumel, A.B.: Modeling the impact of quarantine during an outbreak of Ebola virus disease. Infect. Dis. Model. 4, 12–27 (2019)

Kucharski, A.J., Eggo, R.M., Watson, C.H., Camacho, A., Funk, S., Edmunds, W.J.: Effectiveness of ring vaccination as control strategy for Ebola virus disease. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 22(1), 105–108 (2016)

Bodine, E.N., Cook, C., Shorten, M.: The potential impact of a prophylactic vaccine for Ebola in Sierra Leone. Math. Biosci. Eng. 15(2), 337–359 (2018)

Kelly, J., et al.: Projections of Ebola outbreak size and duration with and without vaccine use in Équateur, Democratic Republic of Congo, as of May 27, 2018. PLoS ONE 14, e0213190 (2019)

Jiang, S., Wang, K., Li, C., Hong, G., Zhang, X., Shan, M., Li, H., Wang, J.: Mathematical models for devising the optimal Ebola virus disease eradication. J. Transl. Med. 15, 124 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-017-1224-6

Diane, S., Njakou, D., Nyabadza, F.: An optimal control model for Ebola virus disease. J. Biol. Syst. 24(1), 1–21 (2016)

Muhammad, D.A., Muhammad, U., Adnan, K., Mudassar, I.: Optimal control analysis of Ebola disease with control strategies of quarantine and vaccination. Infect. Dis. Poverty 5, 72 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-016-0161-6

Area, I., et al.: Ebola model and optimal control with vaccination constraints. J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 14(2), 427–446 (2018)

Rachah, A., Torres, D.F.M.: Mathematical modelling, simulation, and optimal control of the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2015, Article ID 842792 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/842792.

Takaidza, I., Makinde, O.D., Okosun, O.K.: Computational modelling and optimal control of Ebola virus disease with non-linear incidence rate. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 818(1), 012003 (2017)

Meakin, S., Tildesley, M., Davis, E., Keeling, M.: A meta-population model for the 2018 Ebola outbreak in Equateur province in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory: bioRxiv 465062. https://doi.org/10.1101/465062 (2018)

Ivorra, B., Ngom, D., Ramos, A.M.: Version 4: Be-CoDiS: an epidemiological model to predict the risk of human diseases spread between countries. Validation and application to the 2014 Ebola Virus Disease epidemic. Preprint arXiv.org; Cornell Universiy Library, Date:. 1410. 1–32. (2014). http://arxiv.org/abs/1410.6153

Njagarah, J.B., Nyabadza, F.: A meta-population model for cholera transmission dynamics between communities linked by migration. Appl. Math. Comput. 241, 317–331 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2014.05.036

Castillo, C.: Optimal control of an epidemic through educational campaigns. Electron. J. Differ. Equ. 2006, 125 (2006)

Piercy, T.J., Smither, S.J., Steward, J.A., Eastaugh, L., Lever, M.T.: The survival of filo-viruses in liquids, on solid substrates and in a dynamic aerosol. J. Appl. Microbiol. 109(5), 1531–1539 (2010)

Francesconi, P., Yoti, Z., Declich, S., Onek, P.A., Fabiani, M., Olango, J., Andraghetti, R., Rollin, P.E., Opira, C., Greco, D., Salmaso, S.: Ebola hemorrhagic fever transmission and risk factors of contacts, Uganda. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9(11), 1430–1437 (2003)

Chowell, G., Nishiura, H.: Transmission dynamics and control of Ebola virus disease (EVD): a review. BMC Med. 12, 196 (2014)

Youkee, D., Brown, C.S., Lilburn, P., Shetty, N., Brooks, T., Simpson, A., Bentley, N., Lado, M., Kamara, T.B., Walker, N.F., Johnson, O.: Assessment of environmental contamination and environmental decontamination practices within an Ebola holding unit, Freetown, Sierra Leone. PLoS ONE (2015). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145167

Van den Driessche, P., Watmough, J.: Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Math. Biosci. 180, 29–48 (2002)

Castillo-Chavez, C., Feng, Z., Huang, W.: On the computation of \(R_{0}\) and its role on global stability. In: Mathematical Approaches for Emerging and Re Emerging Infectious Diseases: An Introduction, Minneapolis, MN, 1999. IMA Math. Appl., vol. 125, pp. 229–250. Springer, New York (2002)

Korobeinikov, A.: Lyapunov functions and global properties for SEIR and SEIS epidemic models. Math. Med. Biol. 21, 75–83 (2004)

McCluskey, C.C.: Lyapunov functions for tuberculosis models with fast and slow progression. Math. Biosci. Eng. 3, 603–614 (2006)

Shuai, Z., Heesterbeek, J.A.P., Van den Driessche, P.: Extending the type reproduction number to infectious disease control targeting contact between types. J. Math. Biol. 67, 1067–1082 (2013)

Horn, R.A., Johnson, C.R.: Matrix Analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1985)

La Salle, J.P.: The Stability of Dynamical Systems. CBMS-NSF Regional Conference Series in Applied Mathematics. SIAM, Philadelphia, 12 (1976)

Thieme, H.R.: Persistence under relaxed point-dissipativity with an application to en epidemic model. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 24, 407–435 (1993)

Zhao, X.Q.: Uniform persistence and periodic coexistence states in infinite-dimensional periodic semi flows with applications. Can. Appl. Math. Q. 3, 473–495 (1995)

Wang, W.D., Zhao, X.Q.: An epidemic model in a patchy environment. Math. Biosci. 190, 97–112 (2004)

Wang, W.D., Fergola, P., Tenneriello, C.: Innovation diffusion model in patch environment. Appl. Math. Comput. 134, 51–67 (2003)

Castillo-Chavez, C., Song, B.: Dynamical models of tuberculosis and their applications. Math. Biosci. Eng. 1(2), 361–404 (2004)

Levy, B., Edholm, C., Gaoue, O., Kaondera-Shava, R., Kgosimore, M., Lenhart, S., Lephodisa, B., Lungu, E., Marijani, T., Nyabadza, F.: Modeling the role of public health education in Ebola virus disease outbreaks in Sudan. Infect. Dis. Model. 2(3), 323–340 (2017)

Mallela, A., Lenhart, S., Vaidya, N.K.: HIV-TB co-infection treatment: modelling and optimal control theory perspectives. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 307, 143–161 (2016)

Kirschner, D., Lenhart, S., Serbin, S.: Optimal control of the chemotherapy of HIV. J. Math. Biol. 35(7), 775–792 (1997)

WHO: Ebola and Marburg disease epidemics: preparedness, alert, control and evaluation. World Health Organization, WHO/HSE/PED/CED/2014.05 (2014)

Pontryagin, L.S., Boltyanskii, V.T., Gamkrelidze, R.V., Mishchevko, E.F.: The Mathematical Theory of Optimal Processes. Gordon & Breach, New York, 4 (1985)

Fleming, W.H., Rishel, R.W.: Deterministic and Stochastic Optimal Control. Springer, New York (1975)

Lenhart, S., Workman, J.T.: Optimal Controls Applied to Biological Models. Chapman & Hall/CRC, London (1997)

Rivers, C.M., Lofgren, E.T., Marathe, M., Eubank, S., Lewis, B.L.: Modeling the impact of interventions on an epidemic of Ebola in Sierra Leone and Liberia. PLOS Curr. Outbreaks. Edition 1. https://doi.org/10.1371/currents.outbreaks.fd38dd85078565450b0be3fcd78f5ccf (2014)

Ndanguza, D., Tchuenche, J.M., Haario, H.: Statistical data analysis of the 1995 Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Afr. Math. 24, 55–68 (2013)

WHO Ebola Response Team: Ebola virus disease in West Africa-the first 9 months of the epidemic and forward projections. N. Engl. J. Med. 371(16), 1481–1495 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1411100

Bibby, K., Casson, L.W., Stachler, E., Haas, C.N.: Ebola virus persistence in the environment: state of the knowledge and research needs. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2, 2–6 (2015)

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Ebola (Ebola virus disease). http://www.cdc.gov/Ebola/resources/virus-ecology.html (Page last reviewed August 1, 2014)

Fasina, F.O., Shittu, A., Lazarus, D., Tomori, O., Simonsen, L., Viboud, C., Chowell, G.: Transmission dynamics and control of Ebola virus disease outbreak in Nigeria, July to September 2014. Euro Surveill. 19(40), 20920 (2014). http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20920

Towers, S., Patterson-Lomba, O., Castillo-Chavez, C.: Temporal variations in the effective reproduction number of the 2014 West Africa Ebola outbreak. PLOS Curr. September 18 (2014)

Li, M.Y., Graef, J.R., Wang, L., Karsai, J.: Global dynamics of a SEIR model with varying total population size. Math. Biosci. 160, 191–213 (1999)

Acknowledgements

A. Mhlanga, the author, would like to thank the editors and the anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions. He would also like to acknowledge with thanks the support of the Department of Mathematics, University of Zimbabwe.

Availability of data and materials

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article and cited accordingly.

Funding

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author did all the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

None declared.

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

None declared.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Proof of Theorem 1

Rewriting system (3) in expanded form, we have the following system (system (3) is still the same as system (40)):

It is worth noting that, since (40)1 and (40)5 are first order linear equations in \(S_{1}\) and \(S_{2}\), respectively, it is easy to see that \(S_{1}(t) > 0\) if and only if \(S_{2}(t) > 0\). With this remark in mind, we shall prove below that \(S_{1}(t) > 0\) for \(t \geq 0\). To this end, put \(t_{1}^{0} = \sup \lbrace t > 0, S_{1}(t) > 0 \rbrace \) and \(t_{2}^{0} = \sup \lbrace t > 0, S_{2}(t) > 0 \rbrace \).

If \(t_{1}^{0} = +\infty \) and \(t_{2}^{0} = +\infty \), we use the above-mentioned remark to conclude that both \(S_{1}(t)\) and \(S_{2}(t)\) are positive for all \(t \geq 0\). If \(t_{1}^{0} < \infty \) and \(t_{2}^{0} < \infty \), we are going to prove that this leads to a contradiction. By a continuity argument, the solution functions \(S_{1}(t)\) and \(S_{2}(t)\) change sign at least once in the intervals \(J_{1} = [t_{1}^{0},+\infty )\) and \(J_{2} = [t_{2}^{0},+\infty )\), respectively.

Denote by \(t_{1}^{m} \in J_{1}\) and \(t_{2}^{m} \in J_{2}\) the first real numbers such that \(S_{1}(t_{1}^{m}) =0\) and \(S_{2}(t_{2}^{m}) =0\), respectively. We then have

Without loss of generality, suppose that \(t_{1}^{m} \leq t_{2}^{m}\). Then, from system (40), we have

Equation (42) implies that there exists a positive number \(t_{1}^{m_{1}} > t_{1}^{m}\) such that

Putting Eqs. (41) and (43) together and using the continuity of \(S_{1}(t)\), we conclude that \(t_{1}^{m}\) is an extremum of \(S_{1}(t)\). Moreover, since \(S_{1}(t)\) is a differentiable function on \(\mathbb{R}\), one has \(S'(t_{1}^{m}) = 0\). This is a contradiction to (42). Therefore, \(t_{1}^{0} = +\infty \), which implies that \(t_{2}^{0} = +\infty \) as well.

To prove that \(I_{1}(t),D_{1}(t),W_{1}(t),I_{2}(t),D_{2}(t),W_{2}(t) \geq 0\) for all \(t \geq 0\), whenever

we rewrite the corresponding equations in (40) in the form

Since \(S_{1}(t) > 0\), \(S_{2} (t) > 0\) as established above, \(\mathcal{M}\) is a Metzler matrix. Thus (44) is a monotone system. Therefore \(\mathbb{R}^{6}_{+}\) is invariant under the flow of system (44). This completes the proof of positivity of the solutions. □

Appendix 2

Proof of Theorem 2

Adding the total human population we have

Applying the Gronwall inequality to Eq. (46), we have

which implies that \(0 \leq N(t) \leq \frac{b}{\mu _{0}}\) for all \(t \geq 0\) if \(N(0) \leq \frac{b}{\mu _{0}}\). Furthermore, it follows from Eq. (3)3 that we have the relation

to which another application of the Gronwall inequality yields the bounds

where \(D(0) \leq \frac{\overline{v}b}{\underline{\alpha }_{1}\mu _{0}}\).

The boundedness of \(W(t)\) is proved similarly. □

Appendix 3

Proof of Theorem 6

To apply Lemma 1, the following simplifications and change of variables are carried out. Let \(S_{1}=x_{1}\), \(I_{1}=x_{2}\), \(D_{1}=x _{3}\), \(W_{1}=x_{4}\), \(S_{2}=x_{5}\), \(S_{1}^{0} = x_{1}^{0}\). Furthermore, by using the vector notation \(\mathcal{X} = (f_{1},f_{2},f_{3},f_{4},f _{5})\), system (21) can be written in the form \(\frac{d \mathcal{X}}{dt} = F(x)\), with \(F = (f_{1},f_{2},f_{3},f_{4},f_{5})^{T}\), such that

The Jacobian matrix of system (50) at \(\mathcal{E} ^{0}\) is given by

from which it can be shown that

with \(S_{1}^{0} = x_{1}^{0}\) as defined in Eq. (5).

Now, we consider \(\varrho _{1} \beta _{I_{1}}= \beta _{D_{1}}\) and \(\varrho _{2} \beta _{W_{1}} = \beta _{D_{1}}\) regardless of whether \(\varrho _{1},\varrho _{2} \in (0,1)\) or \(\varrho _{1},\varrho _{2} \geq 1\). Taking \(\beta _{D_{1}}\) as the bifurcation parameter and considering that \(\mathcal{R}_{1} = 1\) and solving for \(\beta _{D_{1}}\), we have

The transformed system (50), with \(\beta _{D_{1}} = \beta ^{*}\), has a hyperbolic equilibrium point (like, the linearised system has a simple eigenvalue with zero real part, and all other eigenvalues have negative real part), so that the centre manifold theory [66] can be used to analyse the dynamics of (50) near \(\beta _{D_{1}} = \beta ^{*}\). It can be shown that the Jacobian of system (50) has a right eigenvector associated with the zero eigenvalue given by \(p = (p_{1},p_{2},p_{3},p _{4},p_{5})^{T}\), where

where

The left eigenvectors of \(J(\mathcal{E}^{0})\) associated with the zero eigenvalue at \(\beta _{D_{1}} = \beta ^{*}\) is given by \(q = (q_{1},q_{2},q_{3},q_{4},q_{5})^{T}\), where

Computation of the bifurcation parameters a and b. For the sign of a, it can be shown that the associated non-vanishing partial derivatives of F are given by

From (56) it follows that

This excludes the possibility of a backward bifurcation since \(a<0\). For the sign of b, it is associated with the following non-vanishing partial derivatives of F:

It follows from the expressions in (58) that

Thus, \(a<0\) and \(b>0\) and applying Lemma 1 item (iv), we have established our result. The proof is complete. □

Appendix 4

Proof of Theorem 6

To apply Lemma 1, it is convenient to make the following change of variables:

let \(S_{1}=x_{1}\), \(I_{1}=x_{2}\), \(D_{1}=x_{3}\), \(W_{1}=x_{4}\), \(S_{2}=x_{5}\), \(I _{2}=x_{6}\), \(D_{2}=x_{7}\), \(W_{2}=x_{8}\), \(S_{1}^{0} = x_{1}^{0}\), \(S_{2} ^{0} = x_{2}^{0}\). Further, by using the vector notation \(\mathcal{X} = (f_{1},f_{2},f_{3},f_{4},f_{5},f_{6},f_{7},f_{8})\), system (3) can be written in the form \(\frac{d\mathcal{X}}{dt} = F(x)\), with \(F = (f_{1},f_{2},f_{3},f_{4},f_{5},f_{6},f_{7},f_{8})^{T}\), such that

The Jacobian matrix of system (60) at \(\mathcal{E} ^{0}\) is given by

from which it can be shown that \(\mathcal{R}_{0} = \max \lbrace \mathcal{R} _{1}, \mathcal{R}_{2} \rbrace \), where

Now, we consider \(\varrho _{1} \beta _{I_{1}}= \beta _{D_{1}}\), \(\varrho _{2} \beta _{W_{1}} = \beta _{D_{1}}\), \(\varrho _{3} \beta _{I_{2}}= \beta _{D_{2}}\), \(\varrho _{4} \beta _{W_{2}} = \beta _{D_{2}}\) regardless of whether \(\varrho _{1},\varrho _{2},\varrho _{3},\varrho _{4} \in (0,1)\) or \(\varrho _{1},\varrho _{2},\varrho _{3},\varrho _{4} \geq 1\). Taking \(\beta _{D_{1}}\) as the bifurcation parameter and considering that \(\mathcal{R}_{0} = 1\) and solving for \(\beta _{D_{1}}\), we have

Note that the linearised system of the transformed equation (60) with the bifurcation point \(\beta ^{*}\) has a zero eigenvalue. Hence, the centre manifold theory [66] can be used to analyse the dynamics of system (60) near \(\beta _{I_{1}} = \beta ^{*}\). It can be shown that the Jacobian of system (60) has a right eigenvector associated with the zero eigenvalue given by \(p = (p_{1},p_{2},p_{3},p_{4},p_{5},p_{6},p_{7},p _{8})^{T}\), where

with \(\mathcal{H}\) as defined in Eq. (54).

The left eigenvectors of \(J(\mathcal{E}^{0})\) associated with the zero eigenvalue at \(\beta _{D_{1}} = \beta ^{*}\) is given by \(q = (q_{1},q_{2},q_{3},q_{4},q_{5},q_{6},q_{7},q_{8})^{T}\), where

Computation of the bifurcation parameters a and b. For the sign of a, it can be shown that the associated non-vanishing partial derivatives of F are given by

From (65) it follows that

This excludes the possibility of a backward bifurcation since \(a<0\). For the sign of b, it is associated with the following non-vanishing partial derivatives of F:

It follows from the expressions in (67), and after some algebraic manipulations, we have

Thus, \(a<0\) and \(b>0\) and applying Lemma 1 item (iv), we have established our result. The proof is complete. □

Remark

Suppose that \(\beta _{D_{2}}\) is chosen as a bifurcation parameter. By using the same approach as was used when \(\beta _{D_{1}}\) was taken as the bifurcation parameter in the proof of Theorem 6, we arrive at the same conclusion, that is, \(a < 0\) and \(b > 0\).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mhlanga, A. Dynamical analysis and control strategies in modelling Ebola virus disease. Adv Differ Equ 2019, 458 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-019-2392-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-019-2392-x