Abstract

Background

Increasing evidence implicates oxidative stress (OS) in Alzheimer disease (AD) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Depletion of the brain antioxidant glutathione (GSH) may be important in OS-mediated neurodegeneration, though studies of post-mortem brain GSH changes in AD have been inconclusive. Recent in vivo measurements of the brain and blood GSH may shed light on GSH changes earlier in the disease.

Aim

To quantitatively review in vivo GSH in AD and MCI compared to healthy controls (HC) using meta-analyses.

Method

Studies with in vivo brain or blood GSH levels in MCI or AD with a HC group were identified using MEDLINE, PsychInfo, and Embase (1947–June 2020). Standardized mean differences (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for outcomes using random effects models. Outcome measures included brain GSH (Meshcher-Garwood Point Resolved Spectroscopy (MEGA-PRESS) versus non-MEGA-PRESS) and blood GSH (intracellular versus extracellular) in AD and MCI. The Q statistic and Egger’s test were used to assess heterogeneity and risk of publication bias, respectively.

Results

For brain GSH, 4 AD (AD=135, HC=223) and 4 MCI (MCI=213, HC=211) studies were included. For blood GSH, 26 AD (AD=1203, HC=1135) and 7 MCI (MCI=434, HC=408) studies were included. Brain GSH overall did not differ in AD or MCI compared to HC; however, the subgroup of studies using MEGA-PRESS reported lower brain GSH in AD (SMD [95%CI] −1.45 [−1.83, −1.06], p<0.001) and MCI (−1.15 [−1.71, −0.59], z=4.0, p<0.001). AD had lower intracellular and extracellular blood GSH overall (−0.87 [−1. 30, −0.44], z=3.96, p<0.001). In a subgroup analysis, intracellular GSH was lower in MCI (−0.66 [−1.11, −0.21], p=0.025). Heterogeneity was observed throughout (I2 >85%) and not fully accounted by subgroup analysis. Egger’s test indicated risk of publication bias.

Conclusion

Blood intracellular GSH decrease is seen in MCI, while both intra- and extracellular decreases were seen in AD. Brain GSH is decreased in AD and MCI in subgroup analysis. Potential bias and heterogeneity suggest the need for measurement standardization and additional studies to explore sources of heterogeneity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia representing up to 70% of all cases [1]. In AD, the brain shows hallmark features of amyloid beta (Aβ) plaque accumulation and neurofibrillary tangles formed by hyperphosphorylated tau protein [2], although prior to diagnosis, a series of neuropathological changes and cognitive decline occur [3]. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI), characterized by deficits beyond that anticipated for an individual’s age and education, but without functional impairment, is often the earliest clinical stage of AD [4]. Those with MCI have greater risk of conversion to AD than the normal population, with conversion rates ranging from 10 to 36% over a 2-year period depending on the methods used and the population under study [5].

Currently, there are no approved pharmacological treatments for MCI, although MCI is recognized to provide a window of opportunity to address modifiable risk factors and potentially prevent further progression to dementia [6]. For AD, approved interventions such as cholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA antagonists have modest effects on cognitive decline but are not able to reverse the course of disease [7]. Development of interventions targeting amyloid beta plaques and tau protein tangles also have not been successful [8, 9], and the number of phase 3 trials focused on amyloid intervention has decreased since 2019 [10]. Current phase 2 and 3 clinical trials have shifted focus to other interventions targeting tauopathy, synaptic plasticity, neuroprotection, and/or inflammation [11]. Overall, this suggests the need to identify additional mechanisms that may contribute to progression of AD.

Increasing evidence implicates oxidative stress (OS) with age-related neurodegeneration, neurotoxicity, and neuronal loss [12]. The brain is particularly susceptible to OS due to high metabolism required to maintain synaptic activity, and increased OS is associated with AD and MCI. Literature suggests antioxidant depletion and altered endogenous antioxidant systems precedes OS [12, 13]. Glutathione (GSH) is the primary antioxidant defense molecule in the brain [12]. It is a tripeptide of glutamate, cysteine, and glycine and exerts antioxidant effects through donating a reducing equivalent to a reactive oxygen species to neutralize it [14]. This reaction can occur both non-enzymatically and through catalysis by glutathione peroxidase [14, 15]. In vitro and animal studies suggests that GSH depletion plays an important role in OS-mediated neuronal death and is implicated in neuronal loss in several neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease [16], AD [17], and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [12], making it a potential therapeutic target to prevent or reduce neurodegeneration.

A previous meta-analysis of GSH levels in post-mortem AD brain tissue found no evidence of significant change in GSH in AD compared to controls across several brain regions [18]. The authors also noted that little quantitative post-mortem data were available for MCI. However, the quality of post-mortem data can be variable, as GSH concentration in the brain drops rapidly after death and is affected by many pre- and post-mortem factors [19, 20]. Recent studies have measured in vivo GSH in the brain using magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) and peripherally in the blood [21,22,23]. These in vivo measures are arguably more accurate and provide additional information to help determine if GSH may be considered a therapeutic target.

Therefore, the focus of the present work is to review quantitatively the in vivo GSH changes in the brain and the periphery in AD and MCI compared to controls, using meta-analytic methods.

Methods

Data sources

The methodology outlined by the PRISMA guidelines was used for this review [24]. Articles published before June 2020 were searched using MEDLINE, PsychInfo, Embase, and CINAHL databases for original reports containing in vivo brain or blood measurements of GSH in MCI and/or AD patients and healthy controls. A sample search strategy of brain GSH (for Embase) is detailed in Table 1.

Study selection

Two of the 3 independent reviewers (JC, MT, and JS) assessed each retrieved reference. Screening was done by reviewing reference abstracts to exclude case reports, research in progress, conference abstracts, dissertations, books, and scientific meeting reports. Full-text articles were then assessed. Study inclusion criteria were (1) original clinical studies reporting in vivo GSH levels in the brain, serum, plasma, or blood cells (2); clinical diagnosis of MCI or AD using standardized diagnosis; and (3) inclusion of a medically healthy and cognitively intact control group. Studies measuring post-mortem GSH concentrations without any measures of in vivo GSH were excluded. At least 2 reviewers examined each article for inclusion eligibility independently, results were compared and disagreements regarding inclusion were reached by consensus.

Data extraction

Mean (±SD) GSH concentrations for MCI, AD, and control groups were extracted from each article. Study and participant characteristics were collected using a standardized form. Population characteristics (mean age, sex proportion, years of education, cognitive test scores) and study variables (inclusion criteria, diagnosis method, GSH measurement methodology) were also extracted where available. Reporting the quality and risk of bias items were evaluated by at least 2 raters using items from the Newcastle Ottawa Scale and the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias assessment tool as done previously [25]. Corresponding authors of publications were contacted for missing data. When studies reported multiple brain regions or several blood components (plasma, serum, blood cells), each region or component was extracted as a sub-study. When possible, peripheral GSH measurements were converted to μM, μMol/gHb, or μMol/g protein as appropriate.

Statistical analysis

StataIC 16 was used for the main and subgroup analyses. Standardized mean differences (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each outcome using a random effects model [24]. As studies used different scales of measurement, SMDs were chosen to summarize between group differences since it can better adjust for the different scaling used [26]. Random effects models are preferable when significant heterogeneity is expected because they account for variable underlying effects in estimates of uncertainty, including both within-study and between-study variances [27]. In brain GSH measurements, different acquisition methodologies, internal references, and brain regions have been used. In blood GSH, different assays and blood components were also used. These factors were expected to contribute to significant heterogeneity.

The Q statistic was calculated using a chi-square analysis to assess heterogeneity among combined results. A significant Q statistic indicates diversity in the characteristics of the combined results. Inconsistency was calculated using an I2 statistic to determine the impact of heterogeneity. The risk of publication bias was assessed quantitatively with the Egger’s test [28].

Potential heterogeneity was explored with inverse-variance weighted meta-regression analyses and subgroup analysis. Meta-regression regressed the standard mean differences against mean age, sex proportion, or mean Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores if at least 10 independent studies were included based on Cochrane recommendations. Subgroups were determined a priori to determine if MRS acquisition protocol, internal reference, or brain regions contributed to heterogeneity in brain GSH measurements. In the blood, subgroup analysis was performed to determine if intracellular (erythrocytes and whole blood) or extracellular (plasma and serum) components contributed to heterogeneity in blood GSH, as well as the assay used to measure GSH, namely assays using 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTBN) and o-phthalaldehyde (OPA).

Results

Literature search

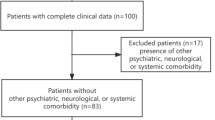

Brain GSH literature findings

The search returned 218 unique records (Fig. 1). Of the records screened, 46 studies were excluded as they were non-clinical studies (including reviews, editorials, and or conference abstracts), 121 studies were excluded because those studies involved non-human subjects, 28 studies were excluded as they were not conducted in AD or MCI patients, 1 study was excluded as it did not have a healthy control group, and 14 studies were excluded as they did not measure GSH in the brain. One paper was excluded as it was an erratum clarification that was not relevant to the results. One additional study was excluded from quantitative analysis as full results could not be obtained. A total of 4 studies were included in the AD brain GSH meta-analysis [29,30,31,32], and 4 studies were included in the MCI analysis [30, 33,34,35] (Table 2). Studies reporting multiple brain locations were analyzed as sub-studies, and when bilateral measures were available, the left and right voxels were averaged. A total of 7 studies and sub-studies were included for AD brain GSH analysis and 8 studies and sub-studies were included for MCI analysis. Assessment of included studies showed a consistently low risk of bias in the brain GSH literature (Table 3).

Blood GSH literature findings

The search returned 299 unique records (Fig. 2). Of the records screened, 40 studies were excluded as they were non-clinical studies (including reviews, editorials, and or conference abstracts); 70 studies were excluded because these studies involved non-human subjects; 81 studies were excluded as they were not conducted in AD or MCI patients; 23 studies were excluded as they were post-mortem studies; 9 studies were excluded as they did not include a healthy control group; 47 studies were excluded as they did not measure GSH in whole blood, plasma, or serum; and 2 were excluded as full results could not be obtained. A total of 27 studies qualified, with 26 of these studies being included in the AD blood GSH meta-analysis [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61], and 7 of these studies being included in the MCI analysis [39, 40, 42, 43, 46, 52, 62]. Studies reporting GSH levels in different blood components (plasma, serum, blood cells) were analyzed as sub-studies, with a total of 33 studies/sub-studies used for AD blood GSH analysis and 8 studies/sub-studies used for MCI blood GSH analysis. The risk of bias was variable in the AD blood GSH literature but consistently low in MCI blood GSH literature (Table 3).

Diagnostic criteria used in AD and MCI

AD patients were identified primarily using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) [63] and/or the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Stroke/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association [64]. The National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association diagnostic guidelines [65], The Dementia Rating Scale-2 [66], International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision [67], and the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease [68] neuropsychological battery were used in 5 GSH studies, respectively [31, 37, 48, 50, 59]. In studies examining blood GSH in AD, 7 studies used the Hachiniski Ischaemic Score (HIS ≤ 4) to differentiate those with AD from those with potential vascular causes [41, 46, 55, 58, 60, 61, 69], and 5 of those studies further used neuroimaging to support diagnosis [55, 58, 60, 61, 69] (Table 2).

For MCI patient samples, the Petersen criteria [70] were commonly used to diagnose MCI, though other studies used revised Petersen criteria [71], or a combination of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, DSM-IV, Clinical Dementia Rating, and Mini-Mental State Examination [34, 62]. While amnestic-type MCI patients were specifically selected in 2 blood GSH studies [42, 43], most of the studies measuring blood GSH and all the studies measuring brain GSH either did not specify or included both amnestic and non-amnestic patients (Table 2).

Brain GSH concentrations and investigating heterogeneity

Brain GSH did not differ in AD (pooled SMD [95%CI] = 0.07 [−1.29, 1.43], p=0.6) and MCI (pooled SMD [95%CI] = −0.43 [−1.19, 0.33], p=0.26) compared to healthy controls. Significant heterogeneity was found in both AD (I2=96.5%, p<0.001) and MCI (I2=92.4%, p<0.001) and supported the use of random effect models. Subgroup analysis evaluating the use of MRS acquisition methods found that Meshcher-Garwood Point Resolved Spectroscopy (MEGA-PRESS) studies had reduced heterogeneity (AD: I2=22.5%, p=0.28, MCI: I2=67.1%, p=0.03), and non-MEGA-PRESS studies remained heterogeneous (I2=94.7%, p<0.001). In the MEGA-PRESS subgroup, brain GSH was lower in both AD (SMD [95%CI] = −1.45 [−1.83, −1.06], z=7.41, p<0.001) (Fig. 3) and MCI (−1.15 [−1.71, −0.59], z=4.0, p<0.001) groups (Fig. 4). Subgroup analyses of different brain regions and use of creatine or water as the reference molecule did not significantly reduce heterogeneity in brain GSH measurements (data not shown), with the exception of the study by Marjanska et al. 2019, use of water as a reference molecule overlapped with MEGA-PRESS studies in AD and MCI (Table 1).

Forest plot displaying brain GSH concentrations in AD and control subjects, with the subgroup of studies using the MEGA-PRESS protocol at the bottom. Shown are the standardized mean differences (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Negative values denote lower GSH in AD subjects while positive values denote higher in GSH in AD compared to controls. Pooled SMD [95% CI] = −0.07 [−1.29, 1.43], z=0.1, p=0.92, MEGA-PRESS subgroup: SMD [95% CI] = −1.45 [−1.83, −1.06], z=7.41, p<0.001. ROI indicates the region of interest: PMC posteromedial cortex, PCC posterior cingulate cortex, OCC occipital cortex, HP hippocampus, FC frontal cortex, ACC anterior cingulate cortex

Forest plot displaying brain GSH concentrations in MCI and control subjects, with the subgroup of studies using the MEGA-PRESS protocol at the bottom. Shown are the standardized mean differences (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Negative values denote lower GSH in MCI subjects while positive values denote higher in GSH in MCI compared to controls. Pooled SMD [95% CI] = −0.43 [−1.19, 0.33], z=1.12, p=0.26, MEGA-PRESS subgroup: SMD [95% CI] = −1.15 [−1.71, −0.59], z=4.0, p<0.001. ROI indicates the region of interest: ACC anterior cingulate cortex, PCC posterior cingulate cortex, FC frontal cortex, HP hippocampus

Blood GSH concentrations and investigating heterogeneity

Blood GSH was lower in AD (SMD [95%CI] = −0.87 [−1.30, −0.44], z=3.96, p<0.001) but not in MCI groups compared to controls (SMD [95%CI] = −0.70 [−1.84, 0.44], z=1.12, p=0.23). Significant heterogeneity was observed for both analyses (AD: I2=95.4%, p<0.001, MCI: I2=97.8%, p<0.001). In AD, both intracellular and extracellular blood GSH were lower (intracellular SMD [95%CI] = −0.80 [−1.34, −0.26], p=0.004; extracellular SMD [95%CI] = −0.86 [−1.49, −0.24], p=0.007) without reduced heterogeneity (AD intracellular: I2=91.3%, p<0.001; extracellular: I2=96.7%, p<0.001) (Fig. 5). Intracellular GSH was lower in MCI (SMD [95%CI] = −0.66 [−1.11, −0.21], p=0.025) with reduced but still significant heterogeneity (MCI intracellular: I2=67.8%, p<0.025) (Fig. 6). Subgroup analysis of GSH assay type did not significantly reduce heterogeneity in blood GSH measurements. Meta-regression showed that studies having a higher proportion of male participants reported greater decreases in GSH levels in AD compared to controls (p = 0.01, I2res = 95.83%, Radj2 = 18.9%) (Fig. 7). Meta-regressions with the mean age and MMSE scores did not significantly reduce heterogeneity (data not shown).

Forest plot displaying blood GSH concentrations in AD and control subjects, by the intracellular and extracellular GSH subgroups. Shown are the standardized mean differences (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Pooled SMD [95% CI] = −0.87 [−1.30, −0.44], z=3.96, p<0.001. Positive values denote higher in GSH in AD while negative values denote higher GSH in control subjects. ROI region of interest

Forest plot displaying blood GSH concentrations in MCI and control subjects by the intracellular and extracellular GSH subgroups. Shown are the standardized mean differences (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Pooled SMD [95% CI] = −0.70 [−1.84, 0.44], z=1.12, p=0.23, the intracellular subgroup SMD [95% CI] = −0.66 [−1.11, −0.21], z=4.0, p=0.004. Positive values denote higher in GSH in MCI while negative values denote higher GSH in control subjects. ROI region of interest

Effect of study bias, publication bias, and small-study effects

In all analyses, the pooled estimated SMDs for the subgroups of studies deemed to have low bias was within the 95% CI of the overall (Table 4), suggesting the impact of studies with higher bias was small. Publication bias was not detected by funnel plots, Egger’s, or trim and fill tests in AD brain GSH literature and MCI blood GSH literature. However, Egger’s test detected a significant risk of publication bias in MCI brain GSH literature (bias [95%CI] = −11.28 [−20.6, −1.95], p=0.03) and AD blood GSH literature (bias [95%CI] = −5.18 [−9.96, −0.40], p=0.035). Blood GSH remained lower in AD compared to controls after adjusting for potential publication bias using trim and fill (estimated SMD [95%CI] = −0.87 [−1.30, −0.44], p<0.001).

Discussion

Brain GSH concentrations

This meta-analysis did not find significant differences between MCI and controls, nor AD vs. controls in in vivo brain GSH overall; however, subgroup analysis suggests that brain GSH may be decreased in AD and MCI in studies using MEGA-PRESS to acquire GSH measurements. GSH is an essential antioxidant in brain cells that detoxifies reactive oxygen species, and in vitro studies have linked GSH homeostasis disruption to oxidative stress in neurological diseases [14, 72]. Increased lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress have been described in AD and MCI [73,74,75]; however, brain GSH has not been as well-characterized. The results of this in vivo brain GSH study mirrors a previous meta-analysis examining post-mortem GSH levels in brain tissue, where they reported that in post-mortem AD brain samples, GSH appeared to be unchanged across several brain regions [18]. It should be noted that GSH data obtained from post-mortem brain samples are variable in quality, as brain GSH is affected by many pre- and post-mortem factors and changes quickly after death [19, 20].

Interestingly, the subgroup analysis of brain GSH suggested that studies using MEGA-PRESS to acquire brain GSH measurements reported lower brain GSH in both AD and MCI patients compared to controls. MEGA-PRESS, a modified PRESS sequence, is a standard technique used in MRS measurements of γ-aminobutyric acid [23] and has been adapted to measure GSH in normal subjects [21, 76] as well as in several patient populations such as schizophrenia [77, 78], Parkinson’s disease [16, 79], and pediatric populations [80]. Studies involving “phantom” test materials suggest that PRESS-acquired GSH may include oxidized GSH (GSSG) and that GSH edited MEGA-PRESS measurements give more precise values at lower GSH concentrations. The existing MRS studies measuring in vivo brain GSH in AD and MCI used several protocols, including STEAM [32, 34], PRESS [33], MEGA-PRESS [30, 35], and J-PRESS [31]. The high heterogeneity and significant risk of bias seen in these in vivo brain GSH studies suggests the need to standardize in vivo GSH measurement methodology. And while qualitative assessment of brain GSH studies is relatively consistent, there may be other factors contributing to heterogeneity. MEGA-PRESS may be a promising protocol, although the current MEGA-PRESS studies reporting brain GSH in MCI and AD were from a single research group, which may have artificially reduced heterogeneity.

Currently, in vivo brain markers in AD and MCI mainly include positron emission tomography scanning of amyloid, tau, and glucose metabolism, as well as brain structural imaging using MRI such as hippocampal atrophy [81]. However, it is now recognized that development and progression of AD is likely due to multiple etiologies, and there is increasing evidence implicating oxidative stress (OS) as an early event in the trajectory of MCI and AD [2, 18, 75]. Thus, examining in vivo brain GSH as a biomarker would complement the current arsenal of brain biomarkers and may aid in identifying and characterizing changes in the early stage of cognitive impairment or those who are at risk.

Blood GSH concentrations

This meta-analysis found that in AD, there was a significant decrease in blood GSH compared to controls, but no difference between MCI and controls. Blood GSH measurements came from extracellular sources in serum and plasma, or intracellular sources in erythrocytes, whole blood (both erythrocytes and leukocytes), or leukocytes. In serum and plasma, reduced GSH is primarily released by hepatocytes for uptake by the kidney, lung, intestine, and other organs [14]. Therefore, in the periphery, extracellular GSH reflects the antioxidant capacity of the liver, and the liver, due to its function in metabolizing xenobiotics and endogenous molecules, has high antioxidant capacity [16]. In the intracellular compartment, erythrocytes perform de novo GSH synthesis [82], GSH is also important in activation of lymphocytes and regulation of immune response [61, 83, 84]. Thus, intracellular GSH may be more sensitive to early changes in GSH homeostasis than extracellular GSH. Indeed, in our subgroup analysis, intracellular blood GSH is decreased in MCI vs. controls, while both intra- and extracellular blood GSH is lowered in AD compared to controls. In our sample, 2 studies in AD [51, 61] specifically reported leukocyte GSH levels with none in MCI. In the context of literature suggesting that sustained immune response and elevation of proinflammatory cytokines in AD pathology [61, 85], additional studies to examine GSH changes in immune cells would be an important future direction. Nonetheless, our peripheral GSH findings suggests that intracellular GSH may be more sensitive to early stages of disease and that extracellular changes become apparent in more severe stages of cognitive impairment such as AD.

A variety of assays were used to measure serum, plasma, and intracellular GSH in MCI and AD populations, including assays using DTBN [36,37,38, 44, 48,49,50, 56,57,58,59], OPA [39, 40, 45, 52, 61], high performance liquid chromatography [42, 43, 46, 51, 53, 55], enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays [69], and other commercial assay kits [60, 62]. Although subgroup analyses found significant heterogeneity regardless of assay type, literature suggests that different assays have specific characteristics and potential pitfalls [82]. OPA-based assays are more sensitive but unstable, which affects accuracy and precision [86], whereas DTNB-based assays allow for determination of biothiols in the presence of other amino acids and polyphenolic antioxidants but are less sensitive [82]. Indeed, the high heterogeneity observed in the present study also corroborates the wide variation of GSH concentrations across different studies and laboratories.

Population-based sources of heterogeneity

Other potential sources of heterogeneity may be related to the populations included in the studies. Sex differences in GSH and enzymes involved in its metabolism have been reported in healthy individuals [87], patients with AD [51], infants [88], and several animal models [89,90,91]. Higher antioxidant defense is seen in females and has been attributed to the ability of estrogen to upregulate expression of antioxidant enzymes [92]. In our analysis of blood GSH studies conducted in AD participants, the proportion of males significantly contributed to heterogeneity. Studies having higher proportion of male participants had larger SMDs, suggesting that AD studies with more male participants reported lower GSH compared to controls. Unfortunately, neither blood nor brain GSH publications in MCI were sufficiently numerous to support similar meta-regressions, but sexual dimorphism in GSH metabolism would be an important covariate to consider in future studies. Another potential source of heterogeneity is the presence of vascular disease in these samples. In studies examining blood GSH in AD, most studies did not examine potential vascular contributions. However, in studies examining brain GSH in AD, most studies excluded those with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. Oxidative stress has been identified as having an important role in cerebrovascular disease and given increasing recognition of the overlap between vascular dementia and AD (“mixed dementia”) and the contribution of vascular changes to AD [93] investigating potential effects of cerebrovascular disease as a covariate would be an important direction for future studies. There were also differences in the MCI populations included with most studies including unknown proportions of amnestic and non-amnestic patients. Amnestic MCI is associated with a higher risk of conversion to AD [94], but those with non-amnestic MCI are a heterogenous group with a higher risk of conversion to other dementias [95]. The MCI patients included in this meta-analysis were a heterogeneous group who were likely not only at risk for AD but also had impairments in multiple domains or had potential cerebrovascular dysfunction. The impact of these differences on GSH remains to be elucidated.

Limitations

Substantial heterogeneity was observed between studies in brain and blood GSH in AD and MCI. There may be other sources of heterogeneity that could not be assessed systematically among the included studies. For instance, many AD studies in this meta-analysis did not report disease severity, limiting the ability to perform subgroup analyses. Other factors which involve a lack of information and potentially contribute to heterogeneity include concomitant illnesses and medications, both of which may affect antioxidant status. All studies were also cross-sectional in nature, which limits conclusions that can be drawn. There was also significant risk of bias in brain GSH measurements in MCI and blood GSH measurements in AD. The meta-analysis was also limited by the small number of studies in MCI and AD studies reporting GSH in the brain. Each brain region was considered as a sub-study, as each region of interest constitutes an individual MRI experiment, although this increases the n and thus decreases variance since a publication can appear more than once. To mitigate this effect, the results from left and right regions were averaged where bilateral measures were available.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis found evidence to suggest decreased blood levels of GSH in AD and intracellular blood GSH in MCI compared to healthy controls. This analysis strengthens the increasing body of work identifying altered antioxidant responses as a potential contributor to cognitive impairment. This study also reveals the variety of assay techniques used to measure GSH in both brain and blood and highlights the need for a uniform measurement methodology. There is a wide range of MRS sequences available to measure in vivo brain GSH, and while the current studies in AD and MCI suggests that MEGA-PRESS is a good candidate for technique standardization, recent advances in MEGA-PRESS have also allowed for simultaneous measurements of pairs of compounds such as GSH/γ-aminobutyric acid and N-acetyl aspartate/N-acetyl aspartyl glutamate in one acquisition [96, 97].

Standardization of measurement techniques, reporting of important patient characteristics such as disease severity, onset, and duration, as well as concomitant illnesses and medications, and additional studies in MCI would allow for better characterization of early biomarkers changes in different stages of cognitive impairment. Indeed, recommendations to incorporate the use of imaging and fluid biomarkers as part of the diagnosis on a broader scale has been recommended by newer National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s’ Association working groups [65, 98, 99] would help to characterize endogenous antioxidant changes in early stages of disease and offer insight into GSH’s potential as a therapeutic target.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed in this current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Alzheimer disease

- Aβ:

-

Amyloid beta

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DSM:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- DTBN:

-

5,5′-Dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid)

- GSH:

-

Glutathione

- HC:

-

Healthy control

- MCI:

-

Mild cognitive impairment

- MEGA-PRESS:

-

Meshcher-Garwood Point-Resolved Spectroscopy

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

- MRS:

-

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- OPA:

-

O-Phthalaldehyde

- OS:

-

Oxidative stress

- PRESS:

-

Point resolved spectroscopy

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean difference

- STEAM:

-

STimulated Echo Acquisition Mode

References

Koyama A, O'Brien J, Weuve J, Blacker D, Metti AL, Yaffe K. The role of peripheral inflammatory markers in dementia and Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(4):433–40.

Kumar A, Singh A. Ekavali. A review on Alzheimer's disease pathophysiology and its management: an update. Pharmacol Rep. 2015;67(2):195–203.

Harrington KD, Lim YY, Ames D, Hassenstab J, Laws SM, Martins RN, et al. Amyloid beta-associated cognitive decline in the absence of clinical disease progression and systemic illness. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2017;8:156-64.

Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA. The neuropathology of probable Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2009;66(2):200–8.

Ward A, Tardiff S, Dye C, Arrighi HM. Rate of conversion from prodromal Alzheimer's disease to Alzheimer's dementia: a systematic review of the literature. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2013;3(1):320–32.

Kasper S, Bancher C, Eckert A, Förstl H, Frölich L, Hort J, et al. Management of mild cognitive impairment (MCI): the need for national and international guidelines. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2020;21(8):579–94.

Knight R, Khondoker M, Magill N, Stewart R, Landau S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in treating the cognitive symptoms of dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2018;45(3-4):131–51.

Agyare EK, Jaruszewski KM, Curran GL, Rosenberg JT, Grant SC, Lowe VJ, et al. Engineering theranostic nanovehicles capable of targeting cerebrovascular amyloid deposits. J Control Release. 2014;185:121–9.

Mehta D, Jackson R, Paul G, Shi J, Sabbagh M. Why do trials for Alzheimer's disease drugs keep failing? A discontinued drug perspective for 2010-2015. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26(6):735–9.

Huang L-K, Chao S-P, Hu C-J. Clinical trials of new drugs for Alzheimer disease. J Biomed Sci. 2020;27(1):18.

Cummings J, Lee G, Ritter A, Sabbagh M, Zhong K. Alzheimer's disease drug development pipeline: 2020. Alzheimer's Dementia. 2020;6(1):e12050.

Aoyama K, Nakaki T. Impaired glutathione synthesis in neurodegeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(10):21021–44.

Gu F, Chauhan V, Chauhan A. Glutathione redox imbalance in brain disorders. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2015;18(1):89–95.

Forman HJ, Zhang H, Rinna A. Glutathione: overview of its protective roles, measurement, and biosynthesis. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30(1-2):1–12.

Ballatori N, Krance SM, Notenboom S, Shi S, Tieu K, Hammond CL. Glutathione dysregulation and the etiology and progression of human diseases. Biol Chem. 2009;390(3):191–214.

Mischley LK, Standish LJ, Weiss NS, Padowski JM, Kavanagh TJ, White CC, et al. Glutathione as a biomarker in Parkinson's disease: associations with aging and disease severity. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:9409363.

Saharan S, Mandal PK. The emerging role of glutathione in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;40(3):519–29.

Zabel M, Nackenoff A, Kirsch WM, Harrison FE, Perry G, Schrag M. Markers of oxidative damage to lipids, nucleic acids and proteins and antioxidant enzymes activities in Alzheimer's disease brain: a meta-analysis in human pathological specimens. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;115:351–60.

Gonzalez-Riano C, Tapia-González S, García A, Muñoz A, DeFelipe J, Barbas C. Metabolomics and neuroanatomical evaluation of post-mortem changes in the hippocampus. Brain Struct Funct. 2017;222(6):2831–53.

Harish G, Venkateshappa C, Mahadevan A, Pruthi N, Srinivas Bharath MM, Shankar SK. Glutathione metabolism is modulated by postmortem interval, gender difference and agonal state in postmortem human brains. Neurochem Int. 2011;59(7):1029–42.

Terpstra M, Marjanska M, Henry PG, Tkác I, Gruetter R. Detection of an antioxidant profile in the human brain in vivo via double editing with MEGA-PRESS. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56(6):1192–9.

Terpstra M, Henry P-G, Gruetter R. Measurement of reduced glutathione (GSH) in human brain using LCModel analysis of difference-edited spectra. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2003;50(1):19–23.

Edden RA, Puts NA, Harris AD, Barker PB, Evans CJ. Gannet: a batch-processing tool for the quantitative analysis of gamma-aminobutyric acid–edited MR spectroscopy spectra. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;40(6):1445–52.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34.

Dinoff A, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu CS, Sherman C, Chan S, et al. The effect of exercise training on resting concentrations of peripheral Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF): a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0163037.

Higgins JPT TJ, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editor. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.2 (updated February 2021)2021.

Takeshima N, Sozu T, Tajika A, Ogawa Y, Hayasaka Y, Furukawa TA. Which is more generalizable, powerful and interpretable in meta-analyses, mean difference or standardized mean difference? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):30.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Mandal PK, Tripathi M, Sugunan S. Brain oxidative stress: detection and mapping of anti-oxidant marker 'Glutathione' in different brain regions of healthy male/female, MCI and Alzheimer patients using non-invasive magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;417(1):43–8.

Shukla D, Mandal PK, Tripathi M, Vishwakarma G, Mishra R, Sandal K. Quantitation of in vivo brain glutathione conformers in cingulate cortex among age-matched control, MCI, and AD patients using MEGA-PRESS. Human Brain Mapping. 2020;41(1):194–217.

Mullins R, Reiter D, Kapogiannis D. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy reveals abnormalities of glucose metabolism in the Alzheimer's brain. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5(3):262–72.

Marjanska M, McCarten JR, Hodges JS, Hemmy LS, Terpstra M. Distinctive neurochemistry in Alzheimer's disease via 7 T in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2019;68(2):559–69.

Duffy SL, Lagopoulos J, Hickie IB, Diamond K, Graeber MB, Lewis SJG, et al. Glutathione relates to neuropsychological functioning in mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2014;10(1):67–75.

Oeltzschner G, Wijtenburg SA, Mikkelsen M, Edden RAE, Barker PB, Joo JH, et al. Neurometabolites and associations with cognitive deficits in mild cognitive impairment: a magnetic resonance spectroscopy study at 7 Tesla. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;73:211–8.

Mandal PK, Saharan S, Tripathi M, Murari G. Brain glutathione levels--a novel biomarker for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(10):702–10.

Arslan A, Tuzun FA, Tamer S, Demir H, Aycan A, Demir C, et al. Change of antioxidant enzyme activities, some metals and lipid peroxidation in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Medica Mediterranea. 2016;32(5):1643–9.

Aybek H, Ercan F, Aslan D, Sahiner T. Determination of malondialdehyde, reduced glutathione levels and APOE4 allele frequency in late-onset Alzheimer's disease in Denizli. Turkey. Clin Biochem. 2007;40(3-4):172–6.

Bai H, Yang B, Yu W, Xiao Y, Yu D, Zhang Q. Cathepsin B links oxidative stress to the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. Exp Cell Res. 2018;362(1):180–7.

Baldeiras I, Santana I, Proenca MT, Garrucho MH, Pascoal R, Rodrigues A, et al. Peripheral oxidative damage in mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimer's Disease. 2008;15(1):117–28.

Bermejo P, Martin-Aragon S, Benedi J, Susin C, Felici E, Gil P, et al. Peripheral levels of glutathione and protein oxidation as markers in the development of Alzheimer's disease from mild cognitive impairment. Free Radic Res. 2008;42(2):162–70.

Bicikova M, Ripova D, Hill M, Jirak R, Havlikova H, Tallova J, et al. Plasma levels of 7-hydroxylated dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) metabolites and selected amino-thiols as discriminatory tools of Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2004;42(5):518–24.

Gironi M, Borgiani B, Farina E, Mariani E, Cursano C, Alberoni M, et al. A global immune deficit in alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment disclosed by a novel data mining process. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2014;43(4):1199–213.

Gironi M, Bianchi A, Russo A, Alberoni M, Ceresa L, Angelini A, et al. Oxidative imbalance in different neurodegenerative diseases with memory impairment. Neurodegener. 2011;8(3):129–37.

Gubandru M, Margina D, Tsitsimpikou C, Goutzourelas N, Tsarouhas K, Ilie M, et al. Alzheimer's disease treated patients showed different patterns for oxidative stress and inflammation markers. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;61:209–14.

Fernandes MA, Proenca MT, Nogueira AJ, Grazina MM, Oliveira LM, Fernandes AI, et al. Influence of apolipoprotein E genotype on blood redox status of Alzheimer's disease patients. Int J Mol Med. 1999;4(2):179–86.

Hernanz A, De la Fuente M, Navarro M, Frank A. Plasma aminothiol compounds, but not serum tumor necrosis factor receptor II and soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products, are related to the cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment patients. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2007;14(3-4):163–7.

Klimiuk A, Maciejczyk M, Choromanska M, Fejfer K, Waszkiewicz N, Zalewska A. Salivary redox biomarkers in different stages of dementia severity. J Clin Med. 2019;8 (6) (no pagination)(840).

Kosenko EA, Aliev G, Kaminsky YG. Relationship between chronic disturbance of 2,3-diphosphoglycerate metabolism in erythrocytes and Alzheimer disease. CNS and Neurological Disorders - Drug Targets. 2016;15(1):113–23.

Krishnan S, Rani P. Evaluation of selenium, redox status and their association with plasma amyloid/tau in Alzheimer's disease. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;158(2):158–65.

Kurup RK, Kurup PA. Hypothalamic digoxin, hemispheric chemical dominance, and Alzheimer's disease. International Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;113(3):361–81.

Liu H, Harrell LE, Shenvi S, Hagen T, Liu RM. Gender differences in glutathione metabolism in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79(6):861–7.

Martinez De Toda I, Miguelez L, Vida C, Carro E, De La Fuente M. Altered redox state in whole blood cells from patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2019;71(1):153–63.

McCaddon A, Hudson P, Hill D, Barber J, Lloyd A, Davies G, et al. Alzheimer's disease and total plasma aminothiols. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(3):254–60.

Mohammad D, Herrmann N, Saleem M, Swartz RH, Oh PI, Bradley J, et al. Validity of a novel screen for cognitive impairment and neuropsychiatric symptoms in cardiac rehabilitation. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):163.

Prendecki M, Florczak-Wyspianska J, Kowalska M, Ilkowski J, Grzelak T, Bialas K, et al. Biothiols and oxidative stress markers and polymorphisms of TOMM40 and APOC1 genes in Alzheimer's disease patients. Oncotarget. 2018;9(81):35207–25.

Puertas MC, Martinez-Martos JM, Cobo MP, Carrera MP, Mayas MD, Ramirez-Exposito MJ. Plasma oxidative stress parameters in men and women with early stage Alzheimer type dementia. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47(8):625–30.

Rani P, Krishnan S, Cathrine CR. Study on analysis of peripheral biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease diagnosis. Frontiers in Neurology. 2017;8 (JUL) (no pagination)(328).

Riveron G, Cuetara E, Hernandez EW, Becquer P, Acosta T, Marin L, et al. Oxidative markers and antioxidant defences in patients diagnosed with probable Alzheimer disease. Pharmacologyonline. 2007;1:20–4.

Sadhu A, Upadhyay P, Agrawal A, Ilango K, Karmakar D, Singh GPI, et al. Management of cognitive determinants in senile dementia of Alzheimer's type: therapeutic potential of a novel polyherbal drug product. Clinical Drug Investigation. 2014;34(12):857–69.

Tabet N, Mantle D, Walker Z, Orrell M. Endogenous antioxidant activities in relation to concurrent vitamins A, C, and E intake in dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(1):7–15.

Vida C, de Toda IM, Garrido A, Carro E, Molina JA, De la Fuente M. Impairment of several immune functions and redox state in blood cells of Alzheimer's disease patients. Relevant role of neutrophils in oxidative stress. Frontiers in Immunology. 2018;8 (JAN) (no pagination)(1974).

Yuan L, Liu J, Ma W, Dong L, Wang W, Che R, et al. Dietary pattern and antioxidants in plasma and erythrocyte in patients with mild cognitive impairment from China. Nutrition. 2016;32(2):193–8.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV: Fourth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, [1994] ©1994; 1994.

McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–44.

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–9.

Griffiths S, Sherman EMS, Strauss E. Dementia rating scale-2. In: Kreutzer JS, DeLuca J, Caplan B, editors. Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology. New York: Springer New York; 2011. p. 810–1.

World Health O. ICD-10 : international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: tenth revision. 2nd ed ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

Fillenbaum GG, van Belle G, Morris JC, Mohs RC, Mirra SS, Davis PC, et al. Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD): the first twenty years. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4(2):96–109.

Mohamed WA, Salama RM, Schaalan MF. A pilot study on the effect of lactoferrin on Alzheimer's disease pathological sequelae: impact of the p-Akt/PTEN pathway. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. 2019;111:714–23.

Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(3):303–8.

Gauthier S, Reisberg B, Zaudig M, Petersen RC, Ritchie K, Broich K, et al. Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet. 2006;367(9518):1262–70.

Bains JS, Shaw CA. Neurodegenerative disorders in humans: the role of glutathione in oxidative stress-mediated neuronal death. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;25(3):335–58.

Pratico D, Sung S. Lipid peroxidation and oxidative imbalance: early functional events in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2004;6(2):171–5.

Butterfield DA, Reed T, Perluigi M, De Marco C, Coccia R, Cini C, et al. Elevated protein-bound levels of the lipid peroxidation product, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, in brain from persons with mild cognitive impairment. Neurosci Lett. 2006;397(3):170–3.

Youssef P, Chami B, Lim J, Middleton T, Sutherland GT, Witting PK. Evidence supporting oxidative stress in a moderately affected area of the brain in Alzheimer’s disease. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1):11553.

Sanaei Nezhad F, Anton A, Parkes LM, Deakin B, Williams SR. Quantification of glutathione in the human brain by MR spectroscopy at 3 Tesla: comparison of PRESS and MEGA-PRESS. Magn Reson Med. 2017;78(4):1257–66.

Matsuzawa D, Hashimoto K. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of the antioxidant defense system in schizophrenia. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15(7):2057–65.

Matsuzawa D, Obata T, Shirayama Y, Nonaka H, Kanazawa Y, Yoshitome E, et al. Negative correlation between brain glutathione level and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a 3T 1H-MRS study. PLoS One. 2008;3(4):e1944.

Mischley LK, Lau RC, Shankland EG, Wilbur TK, Padowski JM. Phase IIb study of intranasal glutathione in Parkinson's disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2017;7(2):289–99.

Raschke F, Noeske R, Dineen RA, Auer DP. Measuring cerebral and cerebellar glutathione in children using (1)H MEGA-PRESS MRS. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39(2):375–9.

Leuzy A, Heurling K, Ashton NJ, Schöll M, Zimmer ER. In vivo detection of Alzheimer's disease. Yale J Biol Med. 2018;91(3):291–300.

Giustarini D, Tsikas D, Colombo G, Milzani A, Dalle-Donne I, Fanti P, et al. Pitfalls in the analysis of the physiological antioxidant glutathione (GSH) and its disulfide (GSSG) in biological samples: an elephant in the room. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2016;1019:21–8.

Yuyun X, Fan Y, Weiping W, Qing Y, Bingwei S. Metabolomic analysis of spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis reveals the potential involvement of glutathione depletion. Innate Immun. 2021;27(1):31–40.

Mak TW, Grusdat M, Duncan GS, Dostert C, Nonnenmacher Y, Cox M, et al. Glutathione primes T cell metabolism for inflammation. Immunity. 2017;46(4):675–89.

Frost GR, Jonas LA, Li YM. Friend, foe or both? Immune activity in Alzheimer's disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:337.

Wang X, Chi D, Song D, Su G, Li L, Shao L. Quantification of Glutathione in Plasma Samples by HPLC Using 4-Fluoro-7-nitrobenzofurazan as a Fluorescent Labeling Reagent. Journal of Chromatographic Science. 2012;50(2):119–22.

Jung CH, Yu JH, Bae SJ, Koh EH, Kim MS, Park JY, et al. Serum gamma-glutamyltransferase is associated with arterial stiffness in healthy individuals. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011;75(3):328–34.

Frosali S, Di Simplicio P, Perrone S, Di Giuseppe D, Longini M, Tanganelli D, et al. Glutathione recycling and antioxidant enzyme activities in erythrocytes of term and preterm newborns at birth. Biol Neonate. 2004;85(3):188–94.

Díaz A, López-Grueso R, Gambini J, Monleón D, Mas-Bargues C, Abdelaziz KM, et al. Sex differences in age-associated type 2 diabetes in rats-role of estrogens and oxidative stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:6734836.

McConnachie LA, Mohar I, Hudson FN, Ware CB, Ladiges WC, Fernandez C, et al. Glutamate cysteine ligase modifier subunit deficiency and gender as determinants of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Toxicol Sci. 2007;99(2):628–36.

Riese C, Michaelis M, Mentrup B, Götz F, Köhrle J, Schweizer U, et al. Selenium-dependent pre- and posttranscriptional mechanisms are responsible for sexual dimorphic expression of selenoproteins in murine tissues. Endocrinology. 2006;147(12):5883–92.

Strehlow K, Rotter S, Wassmann S, Adam O, Grohé C, Laufs K, et al. Modulation of antioxidant enzyme expression and function by estrogen. Circ Res. 2003;93(2):170–7.

Sweeney MD, Montagne A, Sagare AP, Nation DA, Schneider LS, Chui HC, et al. Vascular dysfunction-the disregarded partner of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(1):158–67.

Grundman M, Petersen RC, Ferris SH, Thomas RG, Aisen PS, Bennett DA, et al. Mild cognitive impairment can be distinguished from Alzheimer disease and normal aging for clinical trials. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(1):59–66.

Csukly G, Sirály E, Fodor Z, Horváth A, Salacz P, Hidasi Z, et al. The differentiation of amnestic type MCI from the non-amnestic types by structural MRI. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:52.

Saleh MG, Oeltzschner G, Chan KL, Puts NAJ, Mikkelsen M, Schär M, et al. Simultaneous edited MRS of GABA and glutathione. Neuroimage. 2016;142:576–82.

Chan KL, Puts NA, Schär M, Barker PB, Edden RA. HERMES: hadamard encoding and reconstruction of MEGA-edited spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 2016;76(1):11–9.

Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270–9.

Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(4):535–62.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Mateusz Maciejczyk for providing additional data in the analysis of blood GSH in AD.

Funding

This work is supported by research grants from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (MOP 201803PJ8) and the Alzheimer’s Association (PTC-18-543823) and made possible by Part the Cloud™, as well as the Alzheimer Society Research Program (ASRP #21-11).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception: NH, KL, and JC. Data collection: JC, MT, JS, and CC. Data analysis: JC. Data interpretation: JC, NH, and KL. Manuscript drafting: JC, NH, and KL. Manuscript editing and revision: JC, NH, SB, JR, AA, PO, SM, DG, MJR, SG, and KL. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Supplemental table 1. PRISMA Checklist - Altered central and blood glutathione in Alzheimer Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment: a meta-analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J.J., Thiyagarajah, M., Song, J. et al. Altered central and blood glutathione in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis. Alz Res Therapy 14, 23 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-022-00961-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-022-00961-5