Abstract

Bile acids, which are steroid molecules originating from cholesterol and synthesized in the liver, play a pivotal role in regulating glucose metabolism and maintaining energy balance. Upon release into the intestine alongside bile, they activate various nuclear and membrane receptors, influencing crucial processes. These bile acids have emerged as significant contributors to managing type 2 diabetes mellitus, a complex clinical syndrome primarily driven by insulin resistance. Bile acids substantially lower blood glucose levels through multiple pathways: BA-FXR-SHP, BA-FXR-FGFR15/19, BA-TGR5-GLP-1, and BA-TGR5-cAMP. They also impact blood glucose regulation by influencing intestinal flora, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and bitter taste receptors. Collectively, these regulatory mechanisms enhance insulin sensitivity, stimulate insulin secretion, and boost energy expenditure. This review aims to comprehensively explore the interplay between bile acid metabolism and T2DM, focusing on primary regulatory pathways. By examining the latest advancements in our understanding of these interactions, we aim to illuminate potential therapeutic strategies and identify areas for future research. Additionally, this review critically assesses current research limitations to contribute to the effective management of T2DM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a complex clinical syndrome characterized by disrupted glucose metabolism, due to the interplay of genetic and environmental factors. The proportion of T2DM in patients with diabetes is estimated to be 90%-95% [1,2,3]. The escalating burden of T2DM poses significant challenges to public health, with nearly 500 million affected individuals worldwide, and projections indicating a substantial increase in the future [4]. Insulin resistance and pancreatic β-cell dysfunction lie at the core of T2DM pathogenesis. Insulin resistance refers to the impaired response of target tissues, including adipose, liver, and skeletal muscle, to the actions of insulin, leading to diminished glucose uptake. Simultaneously, β-cell dysfunction results in inadequate insulin secretion to compensate for insulin resistance, further contributing to hyperglycemia [1,2,3].

The etiology of T2DM involves intricate interactions between genetic and environmental factors. Genetic susceptibility, characterized by polymorphisms in genes related to insulin secretion, insulin action, and β-cell function, contributes to an increased predisposition to the disease. Environmental factors, such as sedentary lifestyles, unhealthy dietary patterns, and obesity, interact synergistically with genetic factors, influencing the development of T2DM [2, 5]. Obesity plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of T2DM. Excessive adipose tissue, especially in visceral depots, induces a state of chronic low-grade inflammation and dysregulated secretion of adipokines, impairing insulin signaling pathways and exacerbating insulin resistance. Adipose tissue dysfunction further leads to the release of free fatty acids and adipokines, which contributes to peripheral tissue insulin resistance [6, 7].

Bile acids (BAs), synthesized from cholesterol in the liver and excreted into the bile, extend beyond their traditional role in fat absorption and cholesterol homeostasis. Emerging evidence suggests crucial involvement in metabolic regulation. Acting as signaling molecules, BAs activate various receptors, including the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and the G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor 5 (TGR5), in the liver and peripheral tissues. Activation of these receptors exerts modulatory effects on glucose and lipid metabolism, enhances insulin sensitivity, and maintains energy homeostasis [8,9,10].

The intricate relationship between BAs and the pathogenesis of T2DM has gained significant attention in recent research [11,12,13]. Targeting the bile acid signaling pathways has emerged as a potential therapeutic strategy for T2DM management. Elucidating the precise mechanisms underlying the metabolic effects of BAs and exploring their therapeutic implications hold promise for innovative interventions in T2DM treatment.

Given the rising global prevalence of T2DM and the expanding recognition of BAs' role in metabolic regulation, comprehensive investigations into the fundamental mechanisms of T2DM pathogenesis and the therapeutic potential of bile acid signaling pathways are of utmost importance. Such research endeavors provide a platform for novel insights into T2DM management, fostering the development of innovative therapeutic approaches that hold the potential to enhance patient outcomes in this prevalent metabolic disorder.

Synthesis and recovery of Bile acid

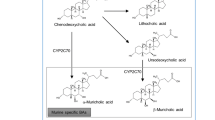

Bile acids are byproducts of cholesterol primarily synthesized in the liver, with about 0.4–0.6 g of the daily synthesized 1–1.5 g cholesterol converted into bile acids. This synthesis occurs through two pathways: the classical pathway and the alternative pathway. The classical pathway, responsible for over 90% of bile acid synthesis, occurs in the hepatic endoplasmic reticulum and is mediated by cholesterol 7-α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) [3, 13, 14]. In its absence, chenodeoxy cholic acid (CDCA) is produced. The acidic pathway is mediated by cholesterol 27-α-hydroxylase (CYP8B1), primarily in peripheral tissues and in macrophages [12, 14,15,16]. (Fig. 1a). These primary bile acids are conjugated to glycine or taurine (approximately 3:1 in humans) by Bile acid CoA: amino acid N-acyltransferase (BAAT). These conjugated bile acids are then absorbed by hepatocytes through bile salt export pump (BSEP) and multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2). They are stored in the gallbladder, and later released into the intestine during feeding [17,18,19]. About 95% of intestinal BA is actively reabsorbed by intestinal cells from the distal ileum through apical sodium-dependent transporter (ASBT) or multidrug resistance-associated protein 3 (MRP3). Bile acids pass through intestinal epithelial cells, facilitated by ileal bile acid binding protein (IABP), to reach the basolateral membrane, and finally pass through the heterodimer of organic solute transporter α and β (OST α / OST β) into the portal vein circulation [12, 13, 17, 20]. Sodium-dependent taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP), located in the hepatocyte basement membrane, is responsible for facilitating sodium-dependent binding. Meanwhile, organic anion transporter (OATP), also found in the hepatocyte basement membrane, handles the uptake of unconjugated BAs. Afterward, active transporters within the hepatic sinusoid membrane of hepatocytes efficiently clear these BAs. These newly dissociated BAs are returned to the hepatocytes with newly formed BAs and then secreted into the bile duct, a process known as enterohepatic circulation [13, 14, 18] (Fig. 2). Approximately 5% of bile salts escape this circulation and are transformed by intestinal microflora. Bile salt hydrolase enzymes (BSH) deconjugate bile salts, and 7-α-dehydroxylase enzymes convert unconjugated bile acids into deoxycholic acid (DCA) and lithocholic acid (LCA). Some deoxycholic acid can be further converted into ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) [16, 21, 22]. (Fig. 1b). Finally, the human bile acid pool primarily consists of CA, CDCA, and DCA in a ratio of 40:40:20 [3, 16]. While in mice, it is mainly composed of Taurocholic acid (TCA), T-β-muricholic acid, and T-α-muricholic acid in a ratio of 60:40 (TCA: TMCA) [12, 14].

The synthesis of primary and secondary bile acids. a CDCA and CA are predominantly synthesized through the classical pathway in the hepatic endoplasmic reticulum, contributing to more than 90% of total bile acid synthesis under normal physiological conditions. This synthesis process is regulated by CYP7A1, and CDCA is produced in the absence of CYP8B1. Subsequently, these primary bile acids are converted into conjugated forms, primarily glycine or taurine-conjugated (in a 3:1 ratio in humans), with the assistance of BAAT. b Within the intestine, BSH plays a predominant role in deconjugating bile acids (TCA, GCA, TCDCA, and GCDCA), converting them back into unconjugated forms. Subsequently, 7-α-dehydroxylase enzymes catalyze the conversion of these unconjugated bile acids into DCA and LCA. Additionally, a minor fraction of deoxycholic acid can be further converted into UDCA by intestinal bacteria's 7-β-hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase enzymes

the enterohepatic circulation of BAs. Initially, primary BAs synthesized in the liver are stored in the gallbladder with the assistance of BSEP and MRP2. In the distal ileum, roughly 95% of intestinal BAs are actively reabsorbed through ASBT and MRP3. Bile acids, facilitated by IABP, traverse intestinal cells and then enter the portal circulation via OST α/OST β. In the hepatocyte basement membrane, NTCP and OATP transport the absorbed BAs to the hepatic sinusoid through active transport mechanisms

The discrepancy in bile acid composition between mice and humans can primarily be attributed to the presence of a species-specific sterol 6-β-hydroxylase enzyme, Cyp2c70, exclusively found in mice. Notably, this enzyme is absent in humans, limiting the conversion of CDCA to α-muricholic acid (α-MCA) in the human hepatic system [23]. In addition to the enzyme disparity, other factors such as dietary structure, intestinal flora, and genetic variations may contribute to the observed differences. The interplay of BSH activity and ileal bile acid binding protein further influences bile acid metabolism, ultimately shaping the distinct bile acid profiles between species [24, 25]. Therefore, when extrapolating findings based on animal models, the applicability of changes in bile acid metabolism in these models to the human system must be carefully considered, especially in the context of T2DM-like diseases. Further studies are needed to fully understand the impact of species-specific bile acid metabolism changes and their relevance to human physiology.

Bile acid and type 2 diabetes mellitus

T2DM is a common disease characterized by abnormal elevation of blood glucose. As mentioned earlier, insulin resistance is considered to be the main pathogenesis of T2DM [2, 5]. Insulin resistance in insulin-sensitive tissues can lead to increased insulin secretion by pancreatic β-cells, but the final result is that β-cells cannot meet the increased demand for insulin. Furthermore, oxidative stress, autophagy and apoptosis of β cells change the function of pancreatic islets [6, 7]. In animal experiments and clinical studies, diabetes and insulin resistance are associated with the increase of 12 α-hydroxylated BA (CA/GCA/DCA) / non-12 α-hydroxylated BA [26,27,28,29,30]. The reason for this may be that abnormally elevated levels of glucose and insulin can promote histone acetylation of CYP7A1 chromatin, thus stimulating the synthesis of CYP7A1 and resulting in an increase in 12 α-hydroxylation BA production. Interestingly, alterations in bile acid composition can, in turn, improve blood glucose disorders. Animal experiments have shown that oral TUDCA can enhance the insulin sensitivity in the liver and skeletal muscle of insulin resistant mice [31]. In a clinical study, it was found that the bile acid chelating agent can improve blood glucose levels in T2DM patients [32]. This mechanism potentially involves the intestinal excretion of bile acids upon their binding with bile acid chelating agents. This process effectively reduces the circulating bile acid content within the enterohepatic circulation. Subsequently, the decrease of the bile acid pool stimulates the liver to up-regulate bile acid synthesis to restore bile acid levels [33].

What’s interesting is that the profiles of BAs in patients with T2DM vary across different studies. Some studies have indicated that serum levels of primary and secondary BAs are significantly higher in T2DM patients compared to non-T2DM patients. Specifically, TCDCA, TDCA, HDCA, GDCA and GLCA show significant increases, while CA and TCA exhibit significant decreases [3]. However, a limitation of this study is the absence of stratified analysis based on the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) value > 2.5. A similar study found no significant difference in total serum bile acid levels between the T2DM group and the normal group. Still, this study revealed that the levels of CA and DCA significantly increased after stratification based on HOMA-IR > 2.5 [34]. In summary, the composition of BAs in T2DM patients requires further analysis through additional clinical studies that consider relevant factors such as age, sex, geographic location, the use of bile acid drugs (e.g., metformin), and metabolic surgery [19, 35, 36].

Bile acids and diabetes drugs (metformin and acarbose)

Metformin is one of the commonly used drugs in the treatment of T2DM, and its mechanism is complex. It has gained increasing attention for its role in reducing blood glucose and improving insulin sensitivity by affecting bile acid metabolism. Some studies have shown that in rat models of T2DM induced by Streptozocin (STZ) injection, oral metformin can inhibit weight gain, reduce CA synthesis, decrease the activity of CYP8B1, and ultimately ameliorate insulin resistance [37]. Simultaneously, it has been observed that metformin can enhance the expression of FXR and Musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene family protein G (MAFG) while inhibiting the expression of CYP8B1 in HepG2 cells. In clinical studies [35], metformin reduces blood glucose levels by increasing the secretion of Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), a phenomenon confirmed in animal experiments. However, it's worth noting that these studies do not measure changes of BA concentrations. In addition, many studies have reported that metformin can inhibit the expression of the bile acid transporter BESP by activating cAMP-PKA and cAMP-AMPK pathways, although it does not appear to affect the expression of CYP7A1 [38,39,40]. This implies that metformin may influence not only bile acid synthesis, but also bile acid secretion and reuptake. However, it's essential to mention that the majority of studies on the effects of metformin on BSEP have primarily focused on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, with limited reports available in diabetic rat models.

Acarbose is an α-glucosidase inhibitor and is commonly used in the treatment of T2DM. There have been relatively few studies on the effect of acarbose on BAs. In a multicenter, randomized controlled clinical trial [41], it was observed that the level of plasma secondary BAs (mainly DCA) and taurine-conjugated BAs decreased in patients with T2DM following treatment with acarbose. The mechanism behind this effect is that acarbose increases the relative abundance of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium while decreasing the relative abundance of Bacteroides.

We have summarized the hypoglycemic mechanisms and glucose outcomes of bile acid-related drugs, as shown in Table 1. In these studies, BAs (CDCA [42, 43], TUDCA [31, 44, 45], HCA [46], GUDCA [47]), FXR inhibitors (HS218[48], Gly-MCA [49, 50]), FXR agonists (Fexaramine [51, 52], GW4064 [53, 54]), FXR/TGR5 agonists (INT-767 [55]), TGR5 agonists (INT-777 [52], RO5527239 [52]), and clinical drugs (Colesevelam [56], Metformin [37, 57, 58], Acarbose [41], Obeticholic acid (OCA) [59,60,61]) all demonstrated hypoglycemic effects by activating different mechanisms. However, one study found that blood glucose increased in mice treated with GW4064 [62]. In fact, the increase in baseline blood glucose and the measurement of blood glucose levels 2 h postprandially may be influencing factors. Additionally, NGM282 is an analogue of fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19), but it has not been found to reduce blood glucose in clinical studies, indicating that FGF19 analogues may have a significant inhibitory effect on hepatic glucose synthesis, but may not directly affect glucose metabolism in other tissues or cells. This requires confirmation in future studies [63].

Bile acids and bariatric metabolic surgery

Bariatric metabolic surgery can also achieve the effect of treating T2DM by changing the composition of BAs and improving insulin resistance [68,69,70,71]. However, there is controversy regarding changes in bile acid concentration after metabolic surgery. Some studies have found that the levels of CA, CDCA, TCA and total BAs decreased significantly 3 months after sleeve gastrectomy (SG), and the concentrations of CA and TCA still decreased significantly 6 months after SG [72, 73]. Furthermore, total BAs remained unchanged 6 months after SG, while primary BAs, including glycine and taurine-conjugated BAs, decreased [74]. In one study, serum C4 levels (a marker of bile acid synthesis) decreased from 23.4 ± 21.1 ng/mL at baseline to 4.9 ± 8.2,8.7 ± 12.1,13.8 ± 12.9 and 18.8 ± 16.8 ng/mL at 1,3,6 and 12 months after SG, suggesting a reduction in bile acid synthesis post-SG [75]. However, other studies found that the total serum BAs concentration increased more than threefold one year after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) [76]. Many studies suggested that the reason may be related to the increase of Fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19) [8, 77]. We believe that the reason for this contradiction lies in the duration of observation. A plausible explanation is that bile acid concentration decreases in the short term (1–3 months) after weight loss, but increases in the long term (1–5 years) after surgery. A second explanation could be the length of the intestinal loop, as different bariatric surgeries will impact pathway of bile acid entering the intestines, affecting bile acid recovery [78]. A third explanation may be that variations in diets, gender and ethnic backgrounds can also lead to diverse changes in BAs following bariatric surgery. Eastern patients tend to have higher initial TBA levels than Western patients, and a high-fat diet decreases primary bile acid synthesis [69, 76]. Additionally, male T2DM patients exhibit decreased TCA levels, while female patients experience reduced CA and TCA levels [3]. These factors can undermine the efficacy of weight loss and need to be taken into account. Furthermore, a patient's history of cholecystectomy may also affect bile acid reentry [79, 80].

Bile acid and intestinal flora

As mentioned earlier, the intestinal flora mediates secondary bile acid synthesis. The most typical manifestation is that human circulating serum BAs are composed of CA, CDCA and DCA, whereas fecal BAs consist of DCA and LCA [81]. Interestingly, bile acid can also affect the composition of the intestinal flora. For example, in patients with T2DM, the relative abundance of Firmicutes decreased, and the relative abundance of Bacteroides increased [82]. Conversely, in rats fed with CA, the relative abundance of Streptomyces increased, while the relative abundance of Bacteroides and actinomycetes decreased [64]. This suggests that BAs may affect glucose metabolism by altering the composition of the intestinal flora. However, the mechanism by which the intestinal flora treats T2DM by influencing bile acid metabolism is still unknown and may be related to FXR and TGR5 [82, 83]. It has been found that acarbose can induce an increase in CDCA, enhance FXR activity, and simultaneously alter intestinal flora. However, their interactions are not certain, so it’s unclear while changes in the intestinal flora affect FXR activity [41]. Similarly, in animal experiments, it was observed that the intestinal flora after RYGB affected FXR and TGR5 by promoting the production of taurine-conjugated Bas [84]. A notable aspect of this study is the use of FXR inhibitor glycine-β-muricholic acid (Gly-MCA) to block intestinal FXR signals, which led to a reduction in the beneficial effects of the intestinal flora on glucose homeostasis. Simultaneously, it was noted that the intestinal flora had no significant impact on glucose tolerance and systemic insulin resistance in TGR5−/− mice. However, it's worth mentioning that this study used obese rat models induced by a high-fat diet rather than the STZ-induced diabetic rat model, and the rats' blood glucose levels did not meet the criteria for T2DM.

The interaction between BAs and the intestinal flora plays a significant role in various physiological processes. BAs have been found to modulate blood glucose levels through multiple mechanisms, including alterations in intestinal pH, changes in the composition of the intestinal flora, and their impact on bacterial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids and lipopolysaccharides [55, 61, 65]. On the other hand, the intestinal flora can influence bile acid metabolism by affecting the activity of enzymes such as BSH and 7-α-dehydroxylase, as well as by regulating bile acid transporters and reabsorption [16, 22]. While current research has primarily focused on animal experiments to investigate the changes in the intestinal flora following treatment with drugs that affect bile acid metabolism (such as FXR inhibitors, CA, OCA, etc.), there is a need for more clinical studies due to the inherent differences in dietary habits and genetic factors between humans and mice. Further research is necessary to understand the effects of BAs on the intestinal flora in patients with T2DM and elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Additionally, it is important to acknowledge that comparing results from different methods of sequencing the intestinal flora (such as high-throughput sequencing, metabolomics, and metagenomics) is scientifically unsound. Therefore, future studies should compare the strengths and limitations of these detection methods to identify an appropriate approach for studying bile acid metabolism.

Hypoglycemic mechanism of bile acid

The hypoglycemic mechanism of bile acid is complex. Currently, the research is primarily focused on changes in bile acid composition and the effects of the bile acid signaling pathways on blood glucose. The pathways involved include the BA-FXR-SHP pathway [48, 51, 53], BA-FXR-FGFR15/19 pathway [77, 85, 86], BA-TGR5-GLP-1 pathway [7, 87, 88] and BA-TGR5-cAMP pathway [43, 44, 52]. Through these various pathways, the ultimate outcome is a modification in bile acid composition, a reductionin in the ratio of 12 α-hydroxylated BAs to non-12 α-hydroxylated BAs, an improvement in insulin resistance, and a decrease in liver gluconeogenesis and insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue. This is achieved by promoting insulin secretion and increasing energy consumption.

FXR and bile acid

The nuclear receptor FXR is a member of the ligand-activated nuclear receptors superfamily of transcription factors. In humans, FXRa is highly expressed in the adrenal gland and liver, while FXRb is highly expressed in the small intestine, large intestine and kidney [89]. Different BAs have varying effects on the activation of FXR, with the order of activation being CDCA > DCA > LCA > CA [13]. FXR plays a pivotal role in regulating glucose metabolism, impacting not only liver bile acid metabolism but also BA secretion and intestinal absorption. As the concentration of liver BAs increases due to intestinal reabsorption, intestinal and liver FXR work together to establish a dynamic balance in BAs by reducing bile acid synthesis and promoting bile acid excretion [90]. In the liver, the activation of FXR by BAs upregulates the expression of genes encoding the inhibitory nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner (SHP), particularly, with an increase in the bile acid pool size. SHP inhibits the activation of several transcription factors, including liver X receptor (LXR), liver receptor homologue-1 (LRH-1) and hepatic nuclear factor-4α (HNF-4α). This subsequently activates CYP7A1 in humans, inhibiting the initial step of cholesterol catabolism [11]. LXR stimulates bile acid synthesis by activating CYP7A1 transcription, but its effects are overridden in the presence of SHP [91]. Moreover, FXR activated by bile acids can increase the levels of MAFG, which subsequently inhibits CYP8B1 in mice. However, MAFG has no effect on CYP7A1. This suggests that MAFG may regulate the ratio of CDCA to CA, thereby controlling bile acid hydrophobicity (by inhibiting CA synthesis without affecting CDCA synthesis), but not the overallbile acid pool size [2, 13]. (Fig. 3a).

a dynamic balance of BAs. Intestinal and hepatic FXR work synergistically to regulate BAs, reducing their synthesis and promoting excretion. Activation of hepatic FXR leads to an upregulation of SHP, which in turn inhibits various transcription factors, including LXR, LRH-1, and HNF-4α, thereby impacting the activities of enzymes such as CYP7A1 and CYP8B1 involved in BA synthesis. Additionally, MAFG, influenced by FXR, may affect the CDCA: CA ratio, thereby influencing the hydrophobicity of BAs without altering the overall BA pool size. b BAs regulate blood glucose levels through FXR. BAs activate FXR within pancreatic β cells, which in turn promotes the release of insulin while inhibiting the release of glucagon and the production of glucose in the liver. SHP competes with HNF-4α, thereby suppressing the expression of genes related to gluconeogenesis. FXR’s direct interaction with ChREBP helps maintain glucose balance by reducing glycolysis and stimulating the storage of glycogen following a meal

BAs promote insulin release, inhibit glucagon release and reduce glucose output from the liver by activating FXR in pancreatic β cells [46, 55, 92]. SHP competes with HNF-4 for binding, thus inhibiting the expression of various genes involved in gluconeogenesis, glucose transport and glycolysis. These genes include glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylate kinase (PEPCK), which play essential roles in inhibiting liver gluconeogenesis, in particular, is the rate-limiting enzyme of hepatic gluconeogenesis. This FXR-mediated inhibition of key genes involved in glucose production leads to improved liver glucose utilization and uptake [48, 91, 93]. However, it should be noted that some data have shown that BAs may upregulate PEPCK through FXR [13, 18]. Furthermore, FXR plays a critical role in maintaining the dynamic balance of glucose through its direct interaction with the carbohydrate response element binding protein (ChREBP). ChREBP is an important transcription factor for glycolytic genes [19, 94]. In the postprandial state, activated FXR reduces glycolysis, promotes glycogen storage and inhibits de novo fat formation by repressing the expression of L-type pyruvate kinase. (Fig. 3b).

It has been observed that in intestinal-specific knockout mice (FXRΔIN), treatments such as Gastric Bypass with Ileal Interposition (GB-IL) or GS3672 [88, 95] did not result in altered blood glucose levels. This phenomenon may be attributed to the inability to activate the intestinal FXR signaling pathway, which does not alter GLP-1 secretion. However, a separate study indicated that, in comparison to FXR−/− mice, liver-specific knockout mice (FXRΔL) and intestinal-specific knockout mice still exhibit metabolic effects following VSG [96]. This study revealed that in FXRΔL and FXRΔIN mice, body weight decreased and blood glucose levels reduced after VSG, whereas these parameters remained unchanged in FXR−/− mice. This findings suggests that liver and intestinal FXR knockout alone are insufficient to eliminate the beneficial effects of VSG. Moreover, this study found that the reduction in intestinal BA levels was not solely due to FXR activation in the intestine and liver. After VSG, Lactobacillus and Firmicutes were significantly increased in FXRΔL and FXRΔIN mice but remained unchanged in FXR-/- mice. Since Lactobacillus carries BSH and Firmicutes carries 7-α-dehydroxylase, this leads to a decrease in taurine-conjugated BAs in FXRΔL and FXRΔIN mice after VSG. These observations suggests that there may be more alternative pathways involved in BA metabolism after VSG, such as increased intestinal permeability and alterations in intestinal flora. These changes contribute to a decrease in BA levels.

In addition, some studies have found variations in BA changes across different regions when using the intestinal-specific FXR receptor agonist Fexaramine [51]. In general, this agonist increases the secretion of FGF15 and GLP-1, promoting insulin secretion and improving glucose tolerance by activating FXR signal pathway. On the contrary, the use of an intestinal-specific FXR receptor inhibitor, Gly-MCA, reduces intestinal ceramide by diminishing intestinal FXR signaling and inhibiting genes related to ceramide synthesis. This reduction in ceramide subsequently decreases hepatic endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and the production of proinflammatory cytokines, leading to improved blood glucose levels and insulin resistance [49]. Interestingly, these two drugs with completely opposite mechanisms yield similar results. However, this phenomenon actually reflects the diverse functions of intestinal FXR. It emphasizes the importance of considering not only functional alterations in FXR, but also potential changes in other mechanisms when investigating the relationship between BAs and FXR. Furthermore, it is crucial to determine whether FXR activation or inactivation varies among different tissues. Previous research has predominantly focused on mouse livers or primary hepatocytes, with limited exploration in other organs such as the intestine and kidney. Expanding the scope of investigation to encompass various tissues will provide a more comprehensive understanding of FXR’s roles.

TGR5 and bile acid

TGR5 is a member of the G-protein-coupled receptor superfamily and is expressed in various tissues, including pancreas β Cells, endocrine cells in the small intestine, thyroid, brown adipose tissue, cardiomyocytes, and macrophages [11, 13]. It is not expressed in hepatocytes, but is instead located in sinusoidal endothelial cells [89]. TGR5 can be activated by a variety of BAs. Different BAs have varying abilities to activate TGR5 receptors, with LCA being the most potent, followed by DCA, CDCA, and CA [97]. Some studies have found that INT-767 can stimulate the secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1(GLP-1) in TGR5−/−mice, but not in FXR−/−mice, indicating that FXR is necessary for GLP-1 secretion. Subsequently, a FXR response element was discovered on the promoter of the TGR5 gene, suggesting that FXR is upstream of TGR5 [88, 98]. However, in the latest study, only CA7S (a sulfated metabolite of bile acid) was found to be increased in bile acid content in cecal contents after SG. Different concentrations of CA7S, however, were unable to activate endogenous FXR in human intestinal Caco-2 cells, suggesting that CA7S may induce TGR5 expression through an independent FXR mechanism [99].

TGR5 has been shown to induce the expression of GLP-1,thereby promoting insulin secretion [46, 61, 100]. With the help of its cofactors α, β and γ, TGR5 activates the protein kinase A (PKA) signaling pathway by stimulating adenylate cyclase, resulting in a rapid increase in intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) production. Then, the PKA pathway leads to the phosphorylation of the cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB) and induces the expression of target genes [43, 44, 52]. In the intestine, endocrine L cells activate TGR5 to increase GLP-1 secretion.GLP-1 promotes insulin secretion by islet β cells and reduces glucagon secretion by islet alpha cells in a glucose-dependent manner [79, 101]. In addition to its glucose-dependent insulin-promoting effect, GLP-1 also shares characteristics with glucagon and induces a feeling of satiety [27, 102] (Fig. 4).

TGR5 and Bas. (1) Activation of TGR5 by BAs induces the expression of GLP-1, promoting insulin secretion through the PKA-CREB pathway. In the intestine, L cells activate TGR5, leading to increased GLP-1 secretion, regulation of glucose-dependent insulin and glucagon secretion, and the induction of satiety. (2) BAs regulate metabolism by enhancing thermogenesis and energy consumption. TGR5 activates thyroid hormones through DIO2, converting inactive T4 into its active form, T3, and increasing PGC1-α for local energy expenditure

In addition, BAs regulate metabolic processes by regulating thermogenesis and increasing energy consumption. One explanation is that TGR5 activates thyroid hormones in brown adipose tissue and muscle cells by stimulating type II iodothyronine deiodinase (DIO2) [103]. The inactive thyroid hormone T4 is ultimately transformed into its active form T3, through the activation of the BA-TGR5-cAMP-DIO2 signaling pathway. This, in turn, increases peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1α (PGC1-α), stimulating localized energy consumption [27, 47, 104]. However, some studies have found that the triiodothyronine levels in mice after RYGB did not differ from those before surgery [103]. Another possible explanation currently under investigation is that more BAs arrives in the colon after metabolic surgery. This activation prompts intestinal endocrine cells to activate the BA-TGR5-GLP-1 axis, leading to increased GLP-1 release, which in turn facilitates muscle glucose absorption [87, 97, 105]. (Fig. 4).

In animal experiments, GW4064, an FXR agonist, have been shown to reduce blood glucose levels and improve insulin resistance by activating FXR and promoting GLP-1 secretion [54, 106]. Similarly, TGR5 agonists have exhibited similar effects [52]. However, in a rat intestinal perfusion model [107], whether through intracavitary perfusion or vascular perfusion, FXR agonists were unable to stimulate GLP-1 secretion, contrary to previous findings. Simultaneously, the TGR5 agonist RO6272296 had no effect on glucagon and insulin secretion in vitro pancreatic perfusion. This may appear inconsistent with previous studies, but it was later discovered that TGR5 was not expressed in neither islet α cells and β cells, which could explain this phenomenon. Despite these conflicting experimental results, both TGR5 and FXR agonists are generally considered beneficial for glucose metabolism.

We have summarized the primary characteristics, hypoglycemic mechanisms, and glucose outcomes of FXR and TGR5 knockout models, as shown in Table 2. When the same site in FXR knockout mice is subjected to different treatment measures, varying results are observed. Similarly, interventions of the same treatment yield diverse outcomes in different parts of the body. The potential reasons for these contradictions are as follows. Firstly, there is a variation in tissue specificity. Differences in the expression levels and regulatory mechanisms of FXR in different tissues may lead to distinct responses to the same treatment. Secondly, the complex nature of signal pathway mechanism plays a role. As a nuclear receptor, FXR participates in intricate signal pathways and transcriptional regulatory networks, resulting in potential cross-effects with other pathways and molecular interactions that give rise to different outcomes. Thirdly, discrepancies in experimental design and methods: differences in experimental design, interventions and evaluation criteria may also contribute to inconsistent results. For instance, variations in intervention dose, timing and experimental techniques can impact the results. In future research, a comprehensive examination of FXR's functions and regulatory mechanisms across various tissues and cell types will be crucial for a more precise understanding of its role in glucose metabolism. Additionally, it is essential to consider potential interactions. Exploring how FXR interacts with other signaling pathways and molecules is necessary to uncover the intricate regulatory networks that may help elucidate the currently contradictory findings.

FGF15/19 and bile acid

FGF19 is a member of the hormone-like FGF protein family, synthesized in the distal small intestine or ileum, gallbladder and brain in humans, while FGF15 is synthesized in mice [28, 114]. It has been reported that there is a strong positive correlation between postprandial total BAs and FGF19, possibly because BAs bind to FXR and stimulate FGF19 synthesis [100]. FGF19 is released from the distal small intestine, enters the portal vein circulation, and acts on the liver. It follows a circadian rhythm, with its peak occurring 90 to 120 min after the rise in serum bile acid levels following meals [115]. Fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs) include FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3 and FGFR4. FGF19 inhibits CYP7A1 by binding to FGFR4, thereby inhibiting BAs synthesis [32, 98]. The first regulatory mechanism involves FGF19 binding to FGFR4 on the plasma membrane of hepatocytes to inhibit CYP7A1 transcription, mediated by c-Jun amino-terminal kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (JNK/ERK). This is an effective SHP independent pathway to inhibit CYP7A1 [51, 55, 62]. The second regulatory mechanism is that FGF19, with the help of β-Klotho (KLB) in hepatocytes, directly activates SHP and inhibits CYP7A1 by binding to FGFR4 [116]. (Fig. 5).

FGF15/19 and BAs. FGF19 inhibits BAs synthesis by binding to FGFR4, thus blocking CYP7A1 through two pathways: SHP-independent inhibition via JNK/ERK and SHP-dependent activation via KLB. FGF19 increases inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis via CREB and downregulates glucose 6-phosphatase gene expression, while activating FGFR4/KLB promotes glycogen synthesis and inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis and adipose tissue glucose disposal, contributing to its hypoglycemic effects

Clinical studies have revealed a negative linear correlation between FGF19 levels and indicators of T2DM severity (including Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and C-peptide levels) [115]. This correlation can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, the increase in FGF19 levels inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis by suppressing the transcriptional activity of CREB, which is a key regulator of PGC-1α. Secondly, FGF19 demonstrates its hypoglycemic effects by down-regulating the expression of glucose 6-phosphatase gene [28]. Lastly, FGF19 activates FGFR4/ β-Klotho in the liver, promoting glycogen synthesis and inhibiting gluconeogenesis in the liver, as well as enhancing glucose disposal in adipose tissue [89, 104]. However, some studies have suggested that the reduction in circulating glucose levels and the improvement in glucose tolerance in obese mice due to FGF-19 are unrelated to insulin secretion. Instead, these effects are attributed to reduced intestinal glucose uptake in the digestive limbs lacking bile acids [7].

In addition, it has recently been considered that the role of FGFR1 in fat and glucose metabolism cannot be ignored. Within the pancreas, FGFR1 is primarily located in β-cells, and a reduction in FGFR1 signaling can lead to β-cell dysfunction. Studies have shown that FGFs-FGFRs binding also activates PI3K/Akt pathway, which mediates metabolism [116, 117].

Other pathway mechanisms and bile acids

In addition to acting on FXR and TGR5, BAs can also regulate blood glucose and affect metabolism through pregnane X receptor, constitutive androstane receptor, vitamin D receptor and other receptors [118]. LCA activates pregnane X receptor and vitamin D receptor, binding to the BA response element-I sequence in the CYP7A1 promoter to inhibit the activity of CYP7A1 promoter [14]. In rodent hepatocytes, DCA activates epidermal growth factor receptor ERB1/ERB2 and insulin receptor through PI3K/AKT/GSK3 signal pathway to participate in the activation of glycogen synthase [13]. BAs can also perform many other biological functions through non-receptor interactions, involving JNK1/2, ERK1/2, Akt1/2 signal pathways, NO metabolism, and cationic channel activation.

Obesity-induced endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress has been implicated in the development of insulin resistance and T2DM [66]. Additionally, an increase in BAs following weight loss may improve glucose regulation by mitigating ER stress in peripheral insulin-sensitive tissues. A study demonstrated that ER stress signals in the liver, adipose tissue, and pancreas decreased after undergoing ileal transposition surgery [119]. Another study showed that oral administration of TUDCA inhibited neointimal proliferation in mouse vascular smooth muscle cells and reduced ER stress in endothelial cells [73]. However, the understanding of the relationship between BAs and ER stress remains limited, and the underlying mechanisms are not fully elucidated. Existing research suggests that ER stress can lead to the upregulation of PERK, promoting islet β-cell apoptosis, inhibiting insulin secretion, and inducing insulin resistance [120, 121]. Conversely, BAs can suppress the expression of ER stress-related proteins, improve insulin resistance, and reduce blood glucose levels by modulating the JNK signaling pathway [31, 66]. Due to the current lack of relevant research, future investigations should focus on two aspects: firstly, evaluating the effects and mechanisms of different types of BAs on ER stress, which could provide valuable insights for the development of hypoglycemic drugs. Secondly, assessing whether there are variations in ER stress among different tissues (e.g., liver, skeletal muscle, adipocytes), as this could identify novel targets for the treatment of T2DM.

Impairment of bitter receptor function has been implicated in the increased prevalence of T2DM, highlighting the potential role of BAs, which are natural bitter substances, in glucose homeostasis. Activation of intestinal bitter taste receptors has been shown to induce GLP-1 secretion, facilitate weight loss, and improve glucose tolerance in rodent models [122]. Previous studies have suggested a possible connection between BAs and intestinal bitter taste receptors. Certain drugs, including KDT501 [123], berberine [124], and Cucurbitacin B [125], have been reported to activate bitter taste receptors and stimulate GLP-1 secretion. Recent research has further demonstrated the ability of LCA and TLCA to activate intestinal bitter taste receptors [126]. Notably, LCA has been found to activate Taste Receptor Type 2 Member 1 (TAS2R1) in humans at a concentration of 0.3 µM, while TLCA activates TAS2R1, TAS2R14, and TAS2R46 at the same concentration. In mice, TLCA activates TAS2108 at 1 µM, and TLCA activates TAS2144, whereas LCA activates TAS2105 at 3 µM. These observations suggest that human gut bitter taste receptors exhibit heightened sensitivity to BAs. However, the underlying mechanism of this activation remains elusive and warrants further investigation, including the exploration of potential involvement of the TGR5 pathway using TGR5 knockout mice. In summary, BAs, acting as natural bitter substances, have the capacity to activate receptors associated with bitterness perception. The impairment of bitter receptor function has been associated with an increased risk of T2DM.

Conclusion

The relationship between bile acid metabolism and T2DM has attracted much attention. In recent years, the research in this field has made rapid progress, and the content involved is more and more extensive. This review mainly discusses the relationship between bile acid and T2DM, summarizes the latest research, analyzes the limitations of existing research and looks forward to the future development trend.

Current studies have shown that BAs are a group of natural compounds produced in the liver and excreted through the intestines. BAs regulate insulin secretion, liver glycogen synthesis and intestinal glucose absorption by activating nuclear receptors such as FXR, TGR5 and FGF15/19 signal transduction pathways, thus affecting glucose metabolism and energy balance. The relationship between BAs and T2DM is also supported in some related clinical studies. For example, data show that there is a significant association between T2DM and serum BAs levels. Bile acid replacement therapy has also been proved to be effective in the improvement of T2DM. We further discussed the molecular mechanisms and signal transduction pathways of bile acid metabolism and T2DM. Investigating the molecular mechanisms in T2DM pathogenesis enhance our comprehension of bile acids' influence on metabolic control. This includes alterations in intestinal flora composition, regulation of genes associated with bile acid synthesis and transport, and modulation of intestinal endocrine hormone secretion. These processes subsequently impact glucose metabolism.

Although the existing studies have preliminarily revealed the relationship between bile acid and T2DM, there are still some limitations. Firstly, due to the interaction between bile acid metabolism and T2DM, it is not clear whether the abnormal bile acid metabolism is the cause or result of T2DM. Secondly, bile acid metabolism is a complex mechanism involving multiple pathways. Current studies mainly focus on the effects of bile acid on FXR and TGR5, ignoring other potential pathways such as endoplasmic reticulum stress, bitter receptor, intestinal flora and so on. At the same time, most studies mainly explore the effects of bile acid on liver and intestinal tract, ignoring the heart, kidney and brain tissue. Thirdly, the experimental models of most studies are based on mice or small-scale people, this method is limited to superficial understanding, and there are certain restrictions on the generalization of conclusions. Fourthly, some studies often lack the concept of personalized treatment, ignoring the differences between different patients. Lastly, some of the experimental results are contradictory, such as in FXR knockout mice, the same site of gene knockout but the results are different. In addition, the change of bile acid concentration during weight loss metabolic surgery is also controversial.

In view of this, there are several potential approaches for future research on BAs and T2DM. Firstly, for the causal relationship between bile acid metabolism and T2DM, Genome-Wide Association Studies and long-term longitudinal studies with large samples can be considered. Secondly, further research on the mechanism can focus on the relationship between bile acid and intestinal flora, bitter receptor and endoplasmic reticulum stress, as well as the effects of bile acid on heart, kidney and brain tissue. Thirdly, to explore the differences in the efficacy of bile acid therapy among different populations, such as genetic variation or intestinal microflora, in order to develop a more individualized treatment plan. Fourthly, the potential side effects of bile acid therapy, such as gastrointestinal problems or abnormal liver function, need to be further studied and evaluated. Ensuring safety is one of the important factors to promote the development of this field. Fifthly, the development of new bile acid analogues or bile acid receptor agonists may have a greater hypoglycemic effect on patients. Lastly, strengthen the multi-disciplinary cooperation of bile acid metabolism and T2DM research, integrate the knowledge of genetics, metabolism, intestinal microbiology, systems biology and other disciplines, in order to deepen the overall understanding of its complex relationship.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- BA:

-

Bile acid

- FXR:

-

Farnesoid X receptor

- TGR5:

-

G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor 5

- CDCA:

-

Chenodeoxy cholic acid

- CA:

-

Cholic acid

- CYP7A1:

-

Cholesterol 7 α-hydroxylase

- C4:

-

α-Hydroxy-4-cholesterol-3-one

- CYP8B1:

-

Cholesterol 12 α-hydroxylase

- CYP27A1:

-

Cytochrome P450 family 27 subfamily A member 1

- BSEP:

-

Bile salt export pump

- MRP2:

-

Multidrug resistance-associated protein 2

- ASBT:

-

Apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter

- MRP3:

-

Multidrug resistance-associated protein 3

- IABP:

-

Ileal bile acid binding protein

- OST α/OST β:

-

Organic solute transporter α/β

- NTCP:

-

Sodium-dependent taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide

- OATP:

-

Organic anion transporter

- DCA:

-

Deoxycholic acid

- LCA:

-

Lithocholic acid

- BSH:

-

Bile salt hydrolase

- UDCA:

-

Ursodeoxycholic acid

- TCA:

-

Taurocholic acid

- HOMA-IR:

-

Homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance

- MAFG:

-

Musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene family protein G

- GLP-1:

-

Glucagon-like peptide 1

- AMPK:

-

AMP-activated protein kinase

- SG:

-

Sleeve gastrectomy

- FGF15/19:

-

Fibroblast growth factor 15/19

- RYGB:

-

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

- Gly-MCA:

-

Glycine-β-muricholic acid

- SHP:

-

Small heterodimer partner

- LXR:

-

Liver X receptor

- LRH-1:

-

Liver receptor homologue-1

- HNF-4α:

-

Hepatic nuclear factor-4α

- G6Pase:

-

Glucose-6-phosphatase

- PEPCK:

-

Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylate kinase

- ChREBP:

-

Carbohydrate response element binding protein

- FXRΔIN:

-

Intestinal-specific FXR knockout mice

- FXRΔL:

-

Liver-specific FXR knockout mice

- ER:

-

Endoplasmic reticulum

- PKA:

-

Protein kinase A

- cAMP:

-

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- DIO2:

-

Type II iodothyronine deiodinase

- PGC1-α:

-

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1-α

- FGFRs:

-

Fibroblast growth factor receptors

- JNK/ERK:

-

C-Jun amino terminal kinase/extracellular signal regulated kinase

- KLB:

-

β-Klotho

- PXR:

-

Pregnane X receptor

- CAR:

-

Constitutive androstane receptor

- VDR:

-

Vitamin D receptor

- TAS2R:

-

Taste 2 receptor

References

Israili ZH. Advances in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Ther. 2011;18(2):117–52.

Wu Y, Zhou A, Tang L, et al. Bile acids: key regulators and novel treatment targets for type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Res. 2020;2020:6138438.

Mantovani A, Dalbeni A, Peserico D, et al. Plasma bile acid profile in patients with and without type 2 diabetes. Metabolites. 2021;11(7):453.

Wang W, Shi Z, Zhang R, et al. Liver proteomics analysis reveals abnormal metabolism of bile acid and arachidonic acid in Chinese hamsters with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Proteomics. 2021;239: 104186.

Zhang Q, Hu N. Effects of metformin on the gut microbiota in obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:5003–14.

Catoi AF, Parvu A, Muresan A, et al. Metabolic mechanisms in obesity and type 2 diabetes: insights from bariatric/metabolic surgery. Obes Facts. 2015;8(6):350–63.

Chen X, Zhang J, Zhou Z. Targeting Islets: metabolic surgery is more than a bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2019;29(9):3001–9.

Huang HH, Lee WJ, Chen SC, et al. Bile acid and fibroblast growth factor 19 regulation in obese diabetics, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease after sleeve gastrectomy. J Clin Med. 2019;8(6):815.

Wu T, Yang M, Xu H, et al. Serum bile acid profiles improve clinical prediction of nonalcoholic fatty liver in T2DM patients. J Proteome Res. 2021;20(8):3814–25.

Jin ZL, Liu W. Progress in treatment of type 2 diabetes by bariatric surgery. World J Diabetes. 2021;12(8):1187–99.

Staels B, Handelsman Y, Fonseca V. Bile acid sequestrants for lipid and glucose control. Curr Diab Rep. 2010;10(1):70–7.

Albaugh VL, Banan B, Ajouz H, et al. Bile acids and bariatric surgery. Mol Aspects Med. 2017;56:75–89.

Kaska L, Sledzinski T, Chomiczewska A, et al. Improved glucose metabolism following bariatric surgery is associated with increased circulating bile acid concentrations and remodeling of the gut microbiome. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(39):8698–719.

di Ciaula A, Garruti G, Lunardi R, et al. Bile acid physiology. Ann Hepatol. 2017;2017(16):S4–14.

Browning MG, Pessoa BM, Khoraki J, et al. Changes in Bile acid metabolism, transport, and signaling as central drivers for metabolic improvements after bariatric surgery. Curr Obes Rep. 2019;8(2):175–84.

Pandak WM, Kakiyama G. The acidic pathway of bile acid synthesis: Not just an alternative pathway(). Liver Res. 2019;3(2):88–98.

Kuipers F, Bloks VW, Groen AK. Beyond intestinal soap–bile acids in metabolic control. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(8):488–98.

Zhang Y, Ning G, Handelsman Y, et al. Gut hormones and the brain. J Diabetes. 2010;2(3):138–45.

Rajani C, Jia W. Bile acids and their effects on diabetes. Front Med. 2018;12(6):608–23.

Tiessen RG, Kennedy CA, Keller BT, et al. Safety, tolerability and pharmacodynamics of apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter inhibition with volixibat in healthy adults and patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18(1):3.

Ridlon JM. Bariatric surgery stirs symbionts to counteract diabesity by CA(7)Sting a liver-generated bile acid into the mix. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29(3):320–2.

Ocana-Wilhelmi L, Martin-Nunez GM, Ruiz-Limon P, et al. Gut microbiota metabolism of bile acids could contribute to the bariatric surgery improvements in extreme obesity. Metabolites. 2021;11(11):733.

Chiang JYL, Ferrell JM. Bile acid metabolism in liver pathobiology. Gene Expr. 2018;18(2):71–87.

Kemis JH, Linke V, Barrett KL, et al. Genetic determinants of gut microbiota composition and bile acid profiles in mice. PLoS Genet. 2019;15(8): e1008073.

Winston JA, Theriot CM. Diversification of host bile acids by members of the gut microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2020;11(2):158–71.

Zhang F, Yuan W, Wei Y, et al. The alterations of bile acids in rats with high-fat diet/streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetes and their negative effects on glucose metabolism. Life Sci. 2019;229:80–92.

Fouladi F, Mitchell JE, Wonderlich JA, et al. The contributing role of bile acids to metabolic improvements after obesity and metabolic surgery. Obes Surg. 2016;26(10):2492–502.

Wang M, Wu Q, Xie H, et al. Effects of sleeve gastrectomy on serum 12alpha-hydroxylated bile acids in a diabetic rat model. Obes Surg. 2017;27(11):2912–8.

Maghsoodi N, Shaw N, Cross GF, et al. Bile acid metabolism is altered in those with insulin resistance after gestational diabetes mellitus. Clin Biochem. 2019;64:12–7.

Wang S, Deng Y, Xie X, et al. Plasma bile acid changes in type 2 diabetes correlated with insulin secretion in two-step hyperglycemic clamp. J Diabetes. 2018;10(11):874–85.

Zangerolamo L, Vettorazzi JF, Solon C, et al. The bile acid TUDCA improves glucose metabolism in streptozotocin-induced Alzheimer’s disease mice model. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2021;521: 111116.

Mazidi M, de Caravatto PP, Speakman JR, et al. Mechanisms of action of surgical interventions on weight-related diseases: the potential role of bile acids. Obes Surg. 2017;27(3):826–36.

Staels B. A review of bile acid sequestrants: potential mechanism(s) for glucose-lowering effects in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Postgrad Med. 2009;121(3 Suppl 1):25–30.

Lee SG, Lee YH, Choi E, et al. Fasting serum bile acids concentration is associated with insulin resistance independently of diabetes status. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2019;57(8):1218–28.

Bahne E, Sun EWL, Young RL, et al. Metformin-induced glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion contributes to the actions of metformin in type 2 diabetes. JCI Insight. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.93936.

Lee G, Park YS, Cho C, et al. Short-term changes in the serum metabolome after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Metabolomics. 2021;17(8):71.

Li M, Hu X, Xu Y, et al. A Possible Mechanism of Metformin in Improving Insulin Resistance in Diabetic Rat Models. Int J Endocrinol. 2019;2019:3248527.

Garzel B, Hu T, Li L, et al. Metformin disrupts bile acid efflux by repressing bile salt export pump expression. Pharm Res. 2020;37(2):26.

Metry M, Krug SA, Karra VK, et al. Differential effects of metformin-mediated BSEP repression on pravastatin and bile acid pharmacokinetics in humans: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Transl Sci. 2022;15(10):2468–78.

Faradonbeh FA, Lastuvkova H, et al. Metformin impairs bile acid homeostasis in ethinylestradiol-induced cholestasis in mice. Chem Biol Interact. 2021;345:109525.

Gu Y, Wang X, Li J, et al. Analyses of gut microbiota and plasma bile acids enable stratification of patients for antidiabetic treatment. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1785.

Zhao L, Xuan Z, Song W, et al. A novel role for farnesoid X receptor in the bile acid-mediated intestinal glucose homeostasis. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(21):12848–61.

Lai Q, Ma Y, Bai J, et al. Mechanisms for bile acids CDCA- and DCA-stimulated hepatic spexin expression. Cells. 2022;11(14):2159.

Silva JA, et al. Effects of tauroursodeoxycholic acid on glucose homeostasis: potential binding of this bile acid with the insulin receptor. Life Sci. 2021;285:120020.

Vettorazzi JF, Ribeiro RA, Borck PC, et al. The bile acid TUDCA increases glucose-induced insulin secretion via the cAMP/PKA pathway in pancreatic beta cells. Metabolism. 2016;65(3):54–63.

Zheng X, Chen T, Jiang R, et al. Hyocholic acid species improve glucose homeostasis through a distinct TGR5 and FXR signaling mechanism. Cell Metab. 2021;33(4):791–803.

Chen B, Bai Y, Tong F, et al. Glycoursodeoxycholic acid regulates bile acids level and alters gut microbiota and glycolipid metabolism to attenuate diabetes. Gut Microbes. 2023;15(1):2192155.

Xu X, Shi X, Chen Y, et al. HS218 as an FXR antagonist suppresses gluconeogenesis by inhibiting FXR binding to PGC-1alpha promoter. Metabolism. 2018;85:126–38.

Jiang C, Xie C, Lv Y, et al. Intestine-selective farnesoid X receptor inhibition improves obesity-related metabolic dysfunction. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10166.

Jiang J, Ma Y, Liu Y, et al. Glycine-beta-muricholic acid antagonizes the intestinal farnesoid X receptor-ceramide axis and ameliorates NASH in mice. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6(12):3363–78.

Pathak P, Xie C, Nichols RG, et al. Intestine farnesoid X receptor agonist and the gut microbiota activate G-protein bile acid receptor-1 signaling to improve metabolism. Hepatology. 2018;68(4):1574–88.

Gillard J, Picalausa C, Ullmer C, et al. Enterohepatic Takeda G-protein coupled receptor 5 agonism in metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and related glucose dysmetabolism. Nutrients. 2022;14(13):2707.

Li L, Zhao H, Chen B, et al. FXR activation alleviates tacrolimus-induced post-transplant diabetes mellitus by regulating renal gluconeogenesis and glucose uptake. J Transl Med. 2019;17(1):418.

Han SY, Song HK, Cha JJ, et al. Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonist ameliorates systemic insulin resistance, dysregulation of lipid metabolism, and alterations of various organs in a type 2 diabetic kidney animal model. Acta Diabetol. 2021;58(4):495–503.

Wang XX, Xie C, Libby AE, et al. The role of FXR and TGR5 in reversing and preventing progression of Western diet-induced hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis in mice. J Biol Chem. 2022;298(11): 102530.

Sedgeman LR, Beysen C, Allen RM, et al. Intestinal bile acid sequestration improves glucose control by stimulating hepatic miR-182-5p in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2018;315(5):G810–23.

Zhang Y, Cheng Y, Liu J, et al. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid functions as a critical effector mediating insulin sensitization of metformin in obese mice. Redox Biol. 2022;57: 102481.

Bravard A, Gerard C, Defois C, et al. Metformin treatment for 8 days impacts multiple intestinal parameters in high-fat high-sucrose fed mice. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):16684.

Wu H, Liu G, He Y, et al. Obeticholic acid protects against diabetic cardiomyopathy by activation of FXR/Nrf2 signaling in db/db mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;858: 172393.

Friedman ES, Li Y, Shen TD, et al. FXR-dependent modulation of the human small intestinal microbiome by the bile acid derivative obeticholic acid. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(6):1741–52.

Carino A, Biagioli M, Marchiano S, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid is a GPBAR1 agonist and resets liver/intestinal FXR signaling in a model of diet-induced dysbiosis and NASH. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2019;1864(10):1422–37.

Farr S, Stankovic B, Hoffman S, et al. Bile acid treatment and FXR agonism lower postprandial lipemia in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2020;318(4):G682–93.

Depaoli AM, Zhou M, Kaplan DD, et al. FGF19 analog as a surgical factor mimetic that contributes to metabolic effects beyond glucose homeostasis. Diabetes. 2019;68(6):1315–28.

Islam KB, Fukiya S, Hagio M, et al. Bile acid is a host factor that regulates the composition of the cecal microbiota in rats. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1773–81.

Liu H, Yokoyama F, Ishizuka S. Metabolic alterations of the gut-liver axis induced by cholic acid contribute to hepatic steatosis in rats. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2023;1868(7): 159319.

Zhang J, Fan Y, Zeng C, et al. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid attenuates renal tubular injury in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Nutrients. 2016;8(10):589.

Borchers A, Pieler T. Programming pluripotent precursor cells derived from Xenopus embryos to generate specific tissues and organs. Genes. 2010;1(3):413–26.

Mak TK, Huang S, Guan B, et al. Bile acid, glucose, lipid profile, and liver enzyme changes in prediabetic patients 1 year after sleeve gastrectomy [J]. BMC Surg. 2020;20(1):329.

Shan CX, Qiu NC, Liu ME, et al. Effects of diet on bile acid metabolism and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetic rats after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass [J]. Obes Surg. 2018;28(10):3044–53.

Koliaki C, Liatis S, le Roux CW, et al. The role of bariatric surgery to treat diabetes: current challenges and perspectives. BMC Endocr Disord. 2017;17(1):50.

Mika A, Kaska L, Proczko-Stepaniak M, et al. Evidence that the length of bile loop determines serum bile acid concentration and glycemic control after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2018;28(11):3405–14.

Ikeda T, Aida M, Yoshida Y, et al. Alteration in faecal bile acids, gut microbial composition and diversity after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Br J Surg. 2020;107(12):1673–85.

de Vuono S, Ricci MA, et al. Serum bile acid levels before and after sleeve gastrectomy and their correlation with obesity-related comorbidities. Obes Surg. 2019;29(8):2517–26.

Belgaumkar AP, Vincent RP, Carswell KA, et al. Changes in Bile acid profile after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy are associated with improvements in metabolic profile and fatty liver disease. Obes Surg. 2016;26(6):1195–202.

Escalona A, Munoz R, Irribarra V, et al. Bile acids synthesis decreases after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(4):763–9.

Jorgensen NB, Dirksen C, Bojsen-Moller KN, et al. Improvements in glucose metabolism early after gastric bypass surgery are not explained by increases in total bile acids and fibroblast growth factor 19 concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(3):E396-406.

Shimizu H, Hatao F, Imamura K, et al. Early effects of sleeve gastrectomy on obesity-related cytokines and bile acid metabolism in morbidly obese japanese patients. Obes Surg. 2017;27(12):3223–9.

Ueno T, Tanaka N, Imoto H, et al. Mechanism of bile acid reabsorption in the biliopancreatic limb after duodenal-jejunal bypass in rats. Obes Surg. 2020;30(7):2528–37.

van den Broek M, de Heide LJM, Sips FLP, et al. Altered bile acid kinetics contribute to postprandial hypoglycaemia after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Int J Obes. 2021;45(3):619–30.

Sang M, Xie C, Qiu S, et al. Cholecystectomy is associated with dysglycaemia: cross-sectional and prospective analyses. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24(8):1656–60.

Guo X, Okpara ES, Hu W, et al. Interactive relationships between intestinal flora and bile acids. Int J Mol Sci. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158343.

Lee CJ, Sears CL, Maruthur N. Gut microbiome and its role in obesity and insulin resistance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020;1461(1):37–52.

Luo M, Yan J, Wu L, et al. Probiotics alleviated nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in high-fat diet-fed rats via gut microbiota/FXR/FGF15 signaling pathway. J Immunol Res. 2021;2021:2264737.

Munzker J, Haase N, Till A, et al. Functional changes of the gastric bypass microbiota reactivate thermogenic adipose tissue and systemic glucose control via intestinal FXR-TGR5 crosstalk in diet-induced obesity. Microbiome. 2022;10(1):96.

Batterham RL, Cummings DE. Mechanisms of diabetes improvement following bariatric/metabolic surgery. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(6):893–901.

Wei M, Shao Y, Liu QR, et al. Bile acid profiles within the enterohepatic circulation in a diabetic rat model after bariatric surgeries. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2018;314(5):G537–46.

Garruti G, di Ciaula A, Wang HH, et al. Cross-talk between bile acids and gastro-intestinal and thermogenic hormones: clues from bariatric surgery. Ann Hepatol. 2017;16:S68–82.

Albaugh VL, Banan B, Antoun J, et al. Role Bile acids and glp-1 in mediating the metabolic improvements of bariatric surgery. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(4):1041–51.

Flynn CR, Albaugh VL, Abumrad NN. Metabolic effects of bile acids: potential role in bariatric surgery. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;8(2):235–46.

Zhao L, Ma P, Peng Y, et al. Amelioration of hyperglycaemia and hyperlipidaemia by adjusting the interplay between gut microbiota and bile acid metabolism: Radix Scutellariae as a case. Phytomedicine. 2021;83: 153477.

Goldfine AB. Modulating LDL cholesterol and glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: targeting the bile acid pathway. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2008;23(5):502–11.

Vitek L, Haluzik M. The role of bile acids in metabolic regulation. J Endocrinol. 2016;228(3):R85-96.

Yan Y, Sha Y, Huang X, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass improves metabolic conditions in association with increased serum bile acids level and hepatic farnesoid X receptor expression in a T2DM rat model. Obes Surg. 2019;29(9):2912–22.

Ploton M, Mazuy C, Gheeraert C, et al. The nuclear bile acid receptor FXR is a PKA- and FOXA2-sensitive activator of fasting hepatic gluconeogenesis. J Hepatol. 2018;69(5):1099–109.

Yang J, van Dijk TH, Koehorst M, et al. Intestinal farnesoid X receptor modulates duodenal surface area but does not control glucose absorption in mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24044132.

Ding L, Zhang E, Yang Q, et al. Vertical sleeve gastrectomy confers metabolic improvements by reducing intestinal bile acids and lipid absorption in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2019388118.

Ahlin S, Cefalo C, Bondia-Pons I, et al. Bile acid changes after metabolic surgery are linked to improvement in insulin sensitivity. Br J Surg. 2019;106(9):1178–86.

Xu G, Song M. Recent advances in the mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of bariatric and metabolic surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2021;17(1):231–8.

Chaudhari SN, Harris DA, Aliakbarian H, et al. Bariatric surgery reveals a gut-restricted TGR5 agonist with anti-diabetic effects. Nat Chem Biol. 2021;17(1):20–9.

Dutia R, Embrey M, O’Brien CS, et al. Temporal changes in bile acid levels and 12alpha-hydroxylation after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery in type 2 diabetes. Int J Obes. 2015;39(5):806–13.

Wang W, Cheng Z, Wang Y, et al. Role of bile acids in bariatric surgery. Front Physiol. 2019;10:374.

Reddy IA, Smith NK, Erreger K, et al. Bile diversion, a bariatric surgery, and bile acid signaling reduce central cocaine reward. PLoS Biol. 2018;16(7): e2006682.

Anhe FF, Varin TV, Schertzer JD, et al. The gut microbiota as a mediator of metabolic benefits after bariatric surgery. Can J Diabetes. 2017;41(4):439–47.

Shapiro H, Kolodziejczyk AA, Halstuch D, et al. Bile acids in glucose metabolism in health and disease [J]. J Exp Med. 2018;215(2):383–96.

Sasaki T, Watanabe Y, Kuboyama A, et al. Muscle-specific TGR5 overexpression improves glucose clearance in glucose-intolerant mice. J Biol Chem. 2021;296: 100131.

Düfer M, Hörth K, Wagner R, et al. Bile acids acutely stimulate insulin secretion of mouse β-cells via farnesoid X receptor activation and K(ATP) channel inhibition. Diabetes. 2012;61(6):1479–89.

Kuhre RE, Wewer Albrechtsen NJ, Larsen O, et al. Bile acids are important direct and indirect regulators of the secretion of appetite- and metabolism-regulating hormones from the gut and pancreas. Mol Metab. 2018;11(84):95.

Qiang S, Tao L, Zhou J, et al. Knockout of farnesoid X receptor aggravates process of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;161: 108033.

Pierre JF, Li Y, Gomes CK, et al. Bile diversion improves metabolic phenotype dependent on farnesoid X receptor (FXR). Obesity. 2019;27(5):803–12.

Li K, Zou J, Li S, et al. Farnesoid X receptor contributes to body weight-independent improvements in glycemic control after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery in diet-induced obese mice. Mol Metab. 2020;37: 100980.

Dehondt H, Marino A, Butruille L, et al. Adipocyte-specific FXR-deficiency protects adipose tissue from oxidative stress and insulin resistance and improves glucose homeostasis. Mol Metab. 2023;69: 101686.

McGavigan AK, Garibay D, Henseler ZM, et al. TGR5 contributes to glucoregulatory improvements after vertical sleeve gastrectomy in mice. Gut. 2017;66(2):226–34.

Makki K, Brolin H, Petersen N, et al. 6α-hydroxylated bile acids mediate TGR5 signalling to improve glucose metabolism upon dietary fiber supplementation in mice. Gut. 2023;72(2):314–24.

Patton A, Khan FH, Kohli R. Impact of fibroblast growth factors 19 and 21 in bariatric metabolism. Dig Dis. 2017;35(3):191–6.

Guo JY, Chen HH, Lee WJ, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 19 and fibroblast growth factor 21 regulation in obese diabetics, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease after gastric bypass. Nutrients. 2022;14(3):645.

Bozadjieva N, Heppner KM, Seeley RJ. Targeting FXR and FGF19 to treat metabolic diseases-lessons learned from bariatric surgery. Diabetes. 2018;67(9):1720–8.

Wang Y, Dang N, Sun P, et al. The effects of metformin on fibroblast growth factor 19, 21 and fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 in high-fat diet and streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Endocr J. 2017;64(5):543–52.

Zarrinpar A, Loomba R. Review article: the emerging interplay among the gastrointestinal tract, bile acids and incretins in the pathogenesis of diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36(10):909–21.

Cummings BP, Bettaieb A, Graham JL, et al. Bile-acid-mediated decrease in endoplasmic reticulum stress: a potential contributor to the metabolic benefits of ileal interposition surgery in UCD-T2DM rats. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6(2):443–56.

Lee JH, Lee J. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and its role in pancreatic β-cell dysfunction and senescence in type 2 diabetes. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(9):4843.

Bao X, Li J, Ren C, et al. Aucubin ameliorates liver fibrosis and hepatic stellate cells activation in diabetic mice via inhibiting ER stress-mediated IRE1α/TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome through NOX4/ROS pathway. Chem Biol Interact. 2022;365: 110074.

Sansome DJ, Xie C, Veedfald S, et al. Mechanism of glucose-lowering by metformin in type 2 diabetes: role of bile acids. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(2):141–8.

Kok BP, Galmozzi A, Littlejohn NK, et al. Intestinal bitter taste receptor activation alters hormone secretion and imparts metabolic benefits. Mol Metab. 2018;16:76–87.

Sun S, Yang Y, Xiong R, et al. Oral berberine ameliorates high-fat diet-induced obesity by activating TAS2Rs in tuft and endocrine cells in the gut. Life Sci. 2022;311(Pt A): 121141.

Kim KH, Lee IS, Park JY, et al. Cucurbitacin B induces hypoglycemic effect in diabetic mice by regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase alpha and glucagon-like peptide-1 via bitter taste receptor signaling. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1071.

Ziegler F, Steuer A, di Pizio A, et al. Physiological activation of human and mouse bitter taste receptors by bile acids. Commun Biol. 2023;6(1):612.

Funding

This study was funded by Shanxi Province 136 Revitalization Medical Project Construction Funds (2019XY003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. YH wrote the main manuscript text and XZ. XW, YW, HW, YQ. prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and Tables 1, 2. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, Y., Zhai, X., Wang, X. et al. Research progress on the relationship between bile acid metabolism and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetol Metab Syndr 15, 235 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-023-01207-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-023-01207-6