Abstract

Background

Paragonimiasis is an important and widespread neglected tropical disease. Fifteen Paragonimus species are human pathogens, but two of these, Paragonimus westermani and P. skrjabini, are responsible for the bulk of human disease. Despite their medical and economic significance, there is limited information on the gene content and expression of Paragonimus lung flukes.

Results

The transcriptomes of adult P. westermani and P. skrjabini were studied with deep sequencing technology. Approximately 30 million reads per species were assembled into 21,586 and 25,825 unigenes for P. westermani and P. skrjabini, respectively. Many unigenes showed homology with sequences from other food-borne trematodes, but 1,217 high-confidence Paragonimus-specific unigenes were identified. Analyses indicated that both species have the potential for aerobic and anaerobic metabolism but not de novo fatty acid biosynthesis and that they may interact with host signaling pathways. Some 12,432 P. westermani and P. skrjabini unigenes showed a clear correspondence in bi-directional sequence similarity matches. The expression of shared unigenes was mostly well correlated, but differentially expressed unigenes were identified and shown to be enriched for functions related to proteolysis for P. westermani and microtubule based motility for P. skrjabini.

Conclusions

The assembled transcriptomes of P. westermani and P. skrjabini, inferred proteins, and extensive functional annotations generated for this project (including identified primary sequence similarities to various species, protein domains, biological pathways, predicted proteases, molecular mimics and secreted proteins, etc.) represent a valuable resource for hypothesis driven research on these medically and economically important species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Food-borne trematode (FBT) infections are important neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) with a global public health impact estimated at more than 665 thousand disability-adjusted life years (DALYs); paragonimiasis is arguably the most important of these because it accounts for nearly 30 % of the FBT-related DALYs [1]. Approximately 20 million people already have a Paragonimus infection, and almost 300 million people are at risk of becoming infected [2, 3].

More than 50 species in the genus Paragonimus have been described, although several could be considered synonymous [4]. Fifteen species are known to infect humans, but the P. westermani and P. skrjabini species complexes are responsible for the bulk of disease in Asia, particularly in the People’s Republic of China, which has the heaviest disease burden among 48 endemic countries [3].

The life-cycle of Paragonimus flukes involves complex interactions with three separate hosts [3]. Embryonated eggs expelled in the sputum or feces hatch in freshwater, releasing larvae that undergo rounds of growth and asexual reproduction in the first intermediate host, an aquatic snail. The snails, in turn, release larvae that develop into metacercariae in crustaceans. When infected crustaceans are ingested by a permissive host (typically small carnivores such as canids, felids, murids, mustelids, viverrids, etc.), metacercariae migrate out of the digestive tract and into the lung, where they mature to long-lived, hermaphroditic, sexually reproducing adults within pulmonary cysts. In contrast, metacercariae ingested by a non-permissive often fail to find the lung. They remain in an immature state and migrate through abnormal tissues including the central nervous system (CNS). Paragonimus skrjabini, for example, is poorly adapted to humans and often causes these ectopic infections [3].

Paragonimiasis is commonly diagnosed by detecting parasite eggs in stool or sputum. Unfortunately, the time interval between infection and oviposition is typically 65–90 days [3], and migrating parasites are capable of causing disease much sooner than this [1]. Migration of worms through the abdominal cavity can cause diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever and hives. Parasites in the lung trigger asthma- or tuberculosis-like symptoms with including cough, fever, pleural effusion, chest pain and bloody sputum. Ectopic infections in the CNS can lead to headache, visual loss, or death if left untreated [1]. Paragonimiasis is easily treated with oral praziquantel. However, diagnosis and treatment are often delayed, because of the non-specific nature of the symptoms and the lack of sensitive and reliable diagnostic methods [5].

Apart from widely used phylogenetic markers, Asian Paragonimus species are very poorly represented in pubic sequence repositories. In the year 2015, there were only 456 protein sequences from the genus Paragonimus in NCBI’s non-redundant protein database (NR). This represents a significant hindrance to the biological research that will be needed to promote the development of novel methods for diagnosis, treatment and global control of paragonimiasis. In order to address this need, we have sequenced and characterized the transcriptomes of P. westermani and P. skrjabini adult worms. Transcriptome sequencing is a well-established, efficient, and cost-effective method of gene discovery that has been used to characterize the expressed genes of trematodes and other parasites [6–8].

Thus, our study has provided insights into the biology of two Paragonimus species along with a wealth of novel sequence data that could be explored to test specific hypotheses relating to Paragonimus and other FBTs.

Methods

Parasite material

Freshwater crab intermediate hosts were collected to obtain parasite metacercariae. Crabs of the genus Isolaptamon were collected from Liuyang county (now called Baisha county), Hunan Province, China, a region specifically endemic to P. westermani [9]. Likewise, Sinopotamon denticulatum were collected from Changan county of Shanxi Province, China, a region specifically endemic to P. skrjabini [10]. Metacercariae were isolated from crab tissue as previously described [11]. The shells of the crabs were removed and the soft tissues were processed in 1× phosphate-buffered saline with a meat grinder. The homogenized meat was allowed to settle, and the supernatant was discarded. The sediment was rinsed several times in water, and metacercariae were collected under a dissection microscope. Species identity was confirmed by morphological examination of metacercariae and later by examination of adult parasites [12–15].

Dogs obtained from non-endemic areas and clear of existing infections were inoculated orally with 200–300 P. westermani or P. skrjabini metacercariae. Adult worms were harvested from the lungs 100 days post-infection, washed thoroughly in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80 °C prior to use.

RNA isolation and sequencing

A total of 5 adult P. westermani and 5 adult P. skrjabini were homogenized in 1 ml TRIzol reagent with microcentrifuge pestle, and total RNA was purified from the homogenate using a TRIzol Plus RNA Purification Kit manufacturer’s recommended protocol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and DNase-treated. Samples had very prominent 28S peaks and very small 18S peaks, with RIN values and DV200 values of 8.3 and 71 (P. westermani, concentration 677 ng/μl) and 7.7 and 72 (P. skrjabini, concentration 562 ng/μl), respectively (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Sequencing libraries were prepared from 2 μg total RNA using Illumina's TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Preparation Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Raw reads (100 bp in length) were deposited in the NCBI sequence read archive under BioProject ID PRJNA219632 for P. westermani and PRJNA301597 for P. skrjabini.

RNA-Seq read processing and assembly

Raw reads were subjected to stringent quality control and contaminant filtering as previously described [16]. Briefly, reads were trimmed to remove low quality regions, and filtered based on read length, sequence complexity, and similarity to known or suspected contaminants, including ribosomal RNA [17, 18], bacteria [19], Homo sapiens (GenBank version hs37) and Canis familiaris (GenBank version 3.1). Remaining high-quality, contaminant-free read sets were down-sampled by digital read normalization using khmer (k = 20) [20]. Reads selected in the down-sampling and their mates were assembled using the Trinity de novo RNA-Seq assembler using default parameters [21]. Scripts included in the Trinity software package were used to map the complete, cleaned read set to the assembled transcripts and filter transcripts less than 1 transcript per million reads mapped and less than 1 % of the per unigene expression level [21]. Assembly fragmentation was calculated with respect to Clonorchis sinensis coding sequences (WormBase ParaSite BioProject PRJDA72781) using in-house scripts and is reported as the percentage of reference genes matched to multiple, non-overlapping transcript BLAST hits.

Transcript expression analyses

The complete, cleaned read sets were mapped to the corresponding filtered, high-quality transcript assemblies, and fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments (FPKM) were calculated for each unigene according to an RNA-Seq by expectation-maximization (RSEM) protocol using scripts included in the Trinity software package [21]. Unigenes were ranked according to abundance based on FPKM values. Fold changes were calculated for the corresponding unigenes from the two assemblies. The average fold change plus or minus 1.96 times the standard deviation (corresponding to the top 5th percentile of up-/downregulation) was used as a cut-off to select unigenes that were differentially expressed between the two species.

Protein prediction and functional annotation

Protein sequences were predicted from transcripts using Prot4EST [22] based, in part, on results from BLAST searches against the NCBI non-redundant protein database (NR, downloaded on 15 April 2014) and databases of ribosomal [17, 18] and mitochondrial genes (downloaded from GenBank on 26 July 2013).

Protein translations were compared to known proteins in NR (downloaded on 15 June 2015), Clonorchis sinensis (WormBase ParaSite BioProject PRJDA72781), Opisthorchis viverrini [23], Fasciola hepatica [24] and Paragonimus kellicotti [16] protein sequences by BLASTP, and results were parsed to consider only non-overlapping top hits with e-value ≥ 1e-05. Sequences from Paragonimus species were excluded from NR prior to BLAST searches in order to facilitate identification of genus- and species-specific transcripts. The longest predicted protein isoform of each assembly unigene was also subjected to a reciprocal best BLAST match between the P. skrjabini and P. westermani transcripts with an e-value cut-off of 1e-05.

Predicted proteins were matched to conserved domains (InterPro) and gene ontology (GO) terms using InterProScan [25–27]. Associations with biological pathways (KEGG orthologous groups, pathways and pathway modules) were determined by KEGGscan [28, 29] using version 70 of the KEGG database. KEGG module completion was determined as previously described [30]. Putative proteases and protease inhibitors were identified and classified by comparison with the MEROPS database [31]. Classical secretion signals found within the first 70 N-terminal amino acids and transmembrane domains were predicted with Phobius [32]. All assembled transcripts, predicted proteins, and associated functional annotations are available at Trematode.net [33].

Identification of “host mimic” proteins

The longest isoform of each assembly unigene was compared to proteins from Homo sapiens (NCBI hs38) and the closest sequenced free-living relative, Schmidtea mediterranea (WormBase ParaSite Bioproject PRJNA12585), by BLASTP. Deduced Paragonimus proteins were considered putative “host mimics” when they shared at least 70 % sequence identity over at least 50 % of the length with the human ortholog but less than 50 % identity (if any) with the S. mediterranea ortholog.

Functional enrichment of gene ontology (GO) terms

Functional enrichment of GO terms was calculated using FUNC with a P-value cut-off of 0.01 [34]. In all cases, the target list was comprised of the longest transcript of each unigene associated with the feature of interest and the background list was comprised of the target list plus the longest transcript from each remaining unigene.

Results and discussion

Transcriptome sequencing, assembly and annotation

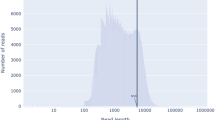

The adult transcriptomes of P. westermani and P. skrjabini were sequenced, assembled de novo, and filtered to consider only high-confidence transcript sequences (Table 1). In each case, related transcripts thought to result from alternative splicing of the same gene were clustered into “unigenes”. A total of 27,842 transcripts from 21,586 unigenes were generated from P. westermani while 35,312 transcripts from 25,825 unigenes were generated from P. skrjabini. Unigenes from the two species had similar length distribution patterns (Fig. 1). We expect these species to encode a gene complement similar in size to those of other FBTs: 13,634 for C. sinensis [35], 16,379 for O. viverrini [23] and 15,740 for F. hepatica [24]. In an ideal assembly, the number of unigenes would equal the number of genes expressed genes in the life-cycle stage or condition studied. However, de novo short read assemblies tend to be fragmented, and this inflates unigene counts. Fragmentation, reported as the percentage of reference genes matched to non-overlapping transcript BLAST hits, was estimated at 24.3 % for P. westermani and 26.7 % for P. skrjabini with respect to the protein coding sequences of C. sinensis. For clarification, this indicates that 24.3 % of all C. sinensis genes are associated with multiple, non-overlapping P. westermani transcripts.

A total of 26,431 and 32,796 unique protein translations were generated from P. westermani and P. skrjabini respectively, and these were annotated based on similarity to sequences in various publicly available databases (Table 1). Complete annotations are provided in Additional file 2: Table S1 and Additional file 3: Table S2. Altogether, functional information (e.g. BLAST matches, structural domains, functional classification, etc.) was deduced for a majority of unigenes, 79.3 % and 80.0 % for P. westermani and P. skrjabini, respectively.

Sequence conservation with relevant trematode species

Due to the sparse representation of Paragonimus sequences in public sequence repositories, only a small fraction of our predicted proteins shared highest sequence similarity with Paragonimus sequences in NR (125 transcripts from 86 P. westermani unigenes and 151 transcripts from 88 P. skrjabini unigenes); a majority of these also had close matches to non-Paragonimus sequences. Predicted proteins from 69.8 % and 60.6 % of P. westermani and P. skrjabini unigenes, respectively, had top matches to non-Paragonimus proteins in NR (Additional file 2: Table S1 and Additional file 3: Table S2) due to the underrepresentation of Paragonimus spp. references in NR. Top hits were mostly to other food-borne trematodes, particularly C. sinensis and O. viverrini. Some 1,217 of the 6,513 P. westermani and 10,171 of the P. skrjabini unigenes with no significant match to non-Paragonimus proteins in NR were homologous in both species (i.e. conserved hypothetical unigenes, Fig. 2). This strengthens the notion that they are indeed valid (not caused by assembly errors), Paragonimus-specific transcripts.

Paragonimus-specific proteins from Paragonimus westermani and Paragonimus skrjabini. Predicted proteins from 6,513 P. westermani unigenes and 10,171 P. skrjabini unigenes found no significant match to non-Paragonimus sequences in NR. Of the unigenes with no BLAST match in NR, 1,217 from each assembly were matched to a non-hit unigene in the other assembly

Comparisons to other trematode species at the primary sequence level indicated that deduced proteins from P. westermani and P. skrjabini share higher sequence identity with proteins from P. kellicotti (the only Paragonimus species with an available adult transcriptome) compared to other FBTs (Table 2). Paragonimus westermani and P. skrjabini may share slightly higher sequence identity with C. sinensis as compared to O. viverrini and F. hepatica; however, this result may be biased by the quality and completeness of the genome assemblies and gene models included in the analysis, as phylogenetic analyses based on mitochondrial markers have previously placed Paragonimus alongside F. hepatica rather than the carcinogenic liver flukes [36, 37].

Metabolic potential of Paragonimus westermani and P. skrjabini

Translated proteins were matched to KEGG orthologous groups and their parent unigenes were binned into broad functional categories (Table 3). The most abundantly populated categories from both assemblies were “signal transduction”, “translation” and “protein folding, sorting, and processing”. Most of the InterPro domains and KEGG orthologous groups that were represented in the adult transcriptomes of P. westermani and P. skrjabini were also represented in the genomes of other food-borne trematodes (Fig. 3). The 1,989 conserved protein domains and 1,419 conserved KOs provide a catalog of functions involved in core biological processes common to all sequenced FBTs. Paragonimus westermani and P. skrjabini shared more InterPro domains with the genome of F. hepatica as compared to the genome of C. sinensis. Some 145 InterPro domains and 195 KEGG orthologous groups were represented in the transcriptome assemblies of both Paragonimus species but absent from the draft genomes of the other two flukes. These Paragonimus conserved/specific KEGG orthologous groups were involved in 28 unique modules, all of which were sparsely populated (Additional file 4: Table S3); therefore, it is difficult to comment on metabolic differences between Paragonimus and other FBTs based solely on the transcriptomes.

Distribution of InterPro domains and KEGG orthologous groups among selected food-borne trematodes. InterPro protein domains and KEGG orthologous groups were assigned to proteins from the complete genomes of Clonorchis sinensis and Fasciola hepatica and to proteins predicted from the Paragonimus westermani and Paragonimus skrjabini transcriptome assemblies, and intersections were determined. Abbreviations: Pw, P. westermani; Cs, C. sinensis; Fh, F. hepatica; Ps, P. skrjabini

The metabolic potential of the two species was assessed at the level of KEGG pathway modules. A KEGG module is considered to be complete when the transcriptome includes the full complement of enzymes (assessed at the level of KO’s) necessary to convert the initial substrate to the final product. Of 95 helminth-relevant KEGG modules [30], 35 were complete in both P. westermani and P. skrjabini. A total of 30 complete modules are shared between the two, with five uniquely complete in each species. However, the difference between the complete modules in one species and the incomplete modules in the other is at most two KO’s, suggesting high functional conservation among the two species.

Other FBTs are known to undergo transitions in energy metabolism over the course of the life-cycle, shifting from aerobic respiration in larval stages to anaerobic respiration in adult stages to adapt to low oxygen microenvironments in host tissues [23, 24, 38]. Given that oxygen tension fluctuates within parasite lung cysts, adult P. westermani are thought to be facultative anaerobes with separate populations of mitochondria capable of either aerobic or anaerobic respiration [39, 40]. Pathway modules associated with aerobic respiration (e.g. M00087: beta-oxidation, M00009: citrate cycle, M00148: succinate dehydrogenase, etc.) were complete in both transcriptomes (Additional file 4: Table S3), and key enzymes involved in anaerobic dismutation (e.g. phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase) were also identified (Additional file 2: Table S1 and Additional file 3: Table S2). Modules related to fatty acid initiation (M00082, two of 13 KOs) and elongation (M00083, one of 14 KOs) are incomplete and poorly represented, so it is unlikely that these processes take place in adult Paragonimus (Additional file 4: Table S3), although fatty acid binding proteins were identified in both species (based on NR matches; comp22449_c0 and comp19053_c0 in P. westermani and comp74673_c0 in P. skrjabini). This is consistent with the hypothesis that trematodes (with the possible exception of C. sinensis [35]) are incapable of de novo fatty acid biosynthesis [23, 24, 41].

Host-parasite interaction

Secreted and excreted proteins are of particular interest in parasites like Paragonimus. They often play important roles in host parasite interaction [41, 42] and are useful targets for diagnostic assays [43–45]. While the N-terminal regions of proteins, which contain secretion signals, are often underrepresented in transcriptome assemblies, 622 P. westermani and 750 P. skrjabini unigenes were found to contain classical signal peptides and no transmembrane domains. This suggests that they may be secreted from cells. Several GO terms related to proteolysis and redox regulation were enriched in the putative secreted unigenes in both species (Additional file 5: Table S4). This is consistent with previous findings that highlighted the prevalence of proteases in trematode excretory-secretory products [46–49] and outlined their important roles in migration through host tissues, feeding and immune evasion [50–53].

Molecular mimicry is a well-known strategy for host manipulation and immune evasion [54]. Interestingly, 122 and 134 predicted proteins from P. westermani and P. skrjabini had far better blast matches to Homo sapiens (a potential host species) than to the free-living, freshwater planarian platyhelminth, Schmidtea mediterranea (Additional file 2: Table S1; Additional file 3: Table S2; see Methods for details). These putative “host mimic” proteins were enriched for kinase and GTPase activity in both species (Additional file 5: Table S4), which may indicate roles in signaling. Parasites like Plasmodium spp., Echinococcus multilocularis and Schistosoma mansoni are known to possess functional homologs of host hormone receptors [54–57]; thus there is a precedent for comingling of host and parasite signaling pathways.

Gene expression in Paragonimus westermani and P. skrjabini

Expression levels were estimated for each unigene in the two transcriptome assemblies (Additional file 2: Table S1; Additional file 3: Table S2). As expected, the top 5 % most highly expressed unigenes in both assemblies were enriched for GO terms related to basic cellular functions such as translation, ATP synthesis and redox regulation (Additional file 5: Table S4). Finding a direct one-to-one correlation between assembly unigenes can be challenging due to the incompleteness and fragmentation of de novo transcript assemblies; however, 12,432 P. westermani and P. skrjabini unigenes were linked through a bi-directional blast match of the longest transcript isoform from each. The expression of matched unigenes tended to be well correlated, but some differentially expressed unigenes were identified (Fig. 4, Table 4). The 303 unigenes that were upregulated in P. westermani were enriched with GO terms related to endopeptidase activity whereas the 249 unigenes upregulated in P. skrjabini were enriched with GO terms related to microtubule based movement (Additional file 5: Table S4). Disparities in gene complement and expression such as these could account for the striking biological differences between P. westermani and P. skrjabini.

Estimated expression of Paragonimus westermani and P. skrjabini assembly unigenes. Corresponding P. westermani and P. skrjabini unigenes identified by bi-directional blast search. The expression levels of each unigene (FPKM) were estimated, and the expression of matched unigenes were compared. a The average fold change plus or minus 1.96 times the standard deviation (corresponding to the top 5th percentile of differential regulation) was used as a cutoff to select unigenes differentially expressed between the two species. b Expression levels of corresponding unigenes were plotted, and differentially expressed unigenes are colored

Diagnostic potential of deduced P. westermani and P. skrjabini proteins

In a previous study, proteins predicted from the de novo transcriptome of P. kellicotti were used as a comparative database in a mass spectrometry study aimed at identifying parasite proteins that could be used as serodiagnostic markers [16]. Paragonimus kellicotti proteins were immunoaffinity-purified from worm lysate with IgG from the serum of infected patients and proteins predicted from 321 transcripts (227 unigenes) were identified by mass spectrometry. Some 205 of the immunoreactive P. kellicotti proteins have blast matches to proteins deduced from the transcriptomes of both P. westermani and P. skrjabini (Additional file 2: Tables S1; Additional file 3: Table S2). Among these conserved proteins was a putative myoglobin isoform proposed as a diagnostic candidate due to its high detection levels in the MS study and its low sequence conservation with trematodes of other genera (Fig. 5). Further studies will be needed to thoroughly explore the utility of this protein as a pan-Paragonimus diagnostic marker.

Alignment of myoglobin orthologs from Paragonimus species and other trematodes. Although assembly fragmentation resulted in a truncated sequence from P. skrjabini, it had greater 90 % similarity with Paragonimus myoglobin (at the amino acid level), with much less similarity to myoglobins from other trematodes. Abbreviations: Pk, Pk34178_txpt1 [16]; Pw, comp20873_c0_seq2; Ps, comp80973_c0_seq3; Cs, C. sinensis gi:349998765; Ov, Opisthorchis viverrini gi: 663047528; Fh, F. hepatica gi:159461074; Sm, S. mansoni gi:256084837; Sj, S. japonicum gi:226487206

Conclusions

This study provides the first insights into gene content and expression in P. westermani and P. skrjabini. Genetic conservation and diversification were assessed to characterize present and absent metabolic pathways. Like other FBTs [23, 24, 41], these species appear capable of both aerobic or anaerobic metabolism, but not de novo fatty acid biosynthesis. For the most part, conserved unigenes were expressed to similar degree in both species. Genes upregulated in P. westermani were enriched for GO terms related to proteolysis while genes upregulated in P. skrjabini were enriched for GO terms related to microtubule based movement. Expressed orthologs of P. kellicotti serodiagnostic antigens were identified in both species, and should be explored in pan-Paragonimus diagnostic assays. We expect that the assembled transcriptomes and the accompanying functional annotations will be a valuable resource for future research, including ongoing genome sequencing projects [33].

Abbreviations

- FBT:

-

Food-borne trematode

- FPKM:

-

Fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- NR:

-

NCBI’s non-redundant protein database

- RSEM:

-

RNA-Seq by expectation maximization

References

Furst T, Keiser J, Utzinger J. Global burden of human food-borne trematodiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(3):210–21.

Keiser J, Utzinger J. Emerging foodborne trematodiasis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(10):1507–14.

Blair D. Paragonimiasis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;766:115–52.

Blair D, Wu B, Chang ZS, Gong X, Agatsuma T, Zhang YN, et al. A molecular perspective on the genera Paragonimus Braun, Euparagonimus Chen and Pagumogonimus Chen. J Helminthol. 1999;73(4):295–9.

Fischer PU, Weil GJ. North American paragonimiasis: epidemiology and diagnostic strategies. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2015;13(6):779–86.

Piao X, Cai P, Liu S, Hou N, Hao L, Yang F, et al. Global expression analysis revealed novel gender-specific gene expression features in the blood fluke parasite Schistosoma japonicum. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(4):e18267.

Liu GH, Xu MJ, Chang QC, Gao JF, Wang CR, Zhu XQ. De novo transcriptomic analysis of the female and male adults of the blood fluke Schistosoma turkestanicum. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9(1):1–10.

Leontovy R, Young ND, Korhonen PK, Hall RS, Tan P, Mikeš L, et al. Comparative transcriptomic exploration reveals unique molecular adaptations of neuropathogenic Trichobilharzia to invade and parasitize its avian definitive host. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(2):e0004406.

Chen C, Chen J, Guo S, Xiong Z, Bi K. A preliminary report of a survey of paragonimiasis prevalence at Baisha Commune of Liuyang County. J Hunan Med Univ. 1980;5(4):302-3.

Chen P, Wu J, Zhang J. An observation of morphology of paragonimiasis pathogens at Chang'an County of Xi'an City. J Fourth Military Med Univ. 1985;(2):1-10.

Liu Q, Wei F, Liu W, Yang S, Zhang X. Paragonimiasis: an important food-borne zoonosis in China. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24(7):318–23.

Blair D, Chang Z, Chen M, Cui A, Wu B, Agatsuma T, et al. Paragonimus skrjabini Chen, 1959 (Digenea: Paragonimidae) and related species in eastern Asia: a combined molecular and morphological approach to identification and taxonomy. Syst Parasitol. 2005;60(1):1–21.

Higo H, Ishii Y. Comparative studies on surface ultrastructure of newly excysted metacercariae of Japanese lung flukes. Parasitol Res. 1987;73(6):541–9.

Blair D, Xu ZB, Agatsuma T. Paragonimiasis and the genus Paragonimus. Adv Parasitol. 1999;42:113–222.

Singh TS, Sugiyama H, Rangsiruji A. Paragonimus and paragonimiasis in India. Indian J Med Res. 2012;136(2):192–204.

McNulty SN, Fischer PU, Townsend RR, Curtis KC, Weil GJ, Mitreva M. Systems biology studies of adult Paragonimus lung flukes facilitate the identification of immunodominant parasite antigens. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(10):e3242.

Pruesse E, Quast C, Knittel K, Fuchs BM, Ludwig W, Peplies J, et al. SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(21):7188–96.

Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D590–596.

The Human Microbiome Consortium. A framework for human microbiome research. Nature. 2012;486(7402):215–21.

Zhang Q, Pell J, Canino-Koning R, Howe AC, Brown CT. These are not the k-mers you are looking for: efficient online k-mer counting using a probabilistic data structure. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e101271.

Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(7):644–52.

Wasmuth J, Blaxter M. Obtaining accurate translations from expressed sequence tags. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;533:221–39.

Young ND, Nagarajan N, Lin SJ, Korhonen PK, Jex AR, Hall RS, et al. The Opisthorchis viverrini genome provides insights into life in the bile duct. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4378.

Cwiklinski K, Dalton JP, Dufresne PJ, La Course J, Williams DJ, Hodgkinson J, et al. The Fasciola hepatica genome: gene duplication and polymorphism reveals adaptation to the host environment and the capacity for rapid evolution. Genome Biol. 2015;16:71.

Jones P, Binns D, Chang HY, Fraser M, Li W, McAnulla C, et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1236–40.

Quevillon E, Silventoinen V, Pillai S, Harte N, Mulder N, Apweiler R, et al. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W116–120.

Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25–9.

Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D109–114.

Wylie T, Martin J, Abubucker S, Yin Y, Messina D, Wang Z, et al. NemaPath: online exploration of KEGG-based metabolic pathways for nematodes. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:525.

Tyagi R, Rosa BA, Lewis WG, Mitreva M. Pan-phylum comparison of nematode metabolic potential. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(5):e0003788.

Rawlings ND, Waller M, Barrett AJ, Bateman A. MEROPS: the database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):23.

Kall L, Krogh A, Sonnhammer EL. Advantages of combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction - the Phobius web server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Web Server issue):W429–432.

Martin J, Rosa BA, Ozersky P, Hallsworth-Pepin K, Zhang X, Bhonagiri-Palsikar V, et al. Helminth.net: expansions to Nematode.net and an introduction to Trematode.net. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D698–706.

Prufer K, Muetzel B, Do HH, Weiss G, Khaitovich P, Rahm E, et al. FUNC: a package for detecting significant associations between gene sets and ontological annotations. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:41.

Huang Y, Chen W, Wang X, Liu H, Chen Y, Guo L, et al. The carcinogenic liver fluke, Clonorchis sinensis: new assembly, reannotation and analysis of the genome and characterization of tissue transcriptomes. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e54732.

Cai XQ, Liu GH, Song HQ, Wu CY, Zou FC, Yan HK, et al. Sequences and gene organization of the mitochondrial genomes of the liver flukes Opisthorchis viverrini and Clonorchis sinensis (Trematoda). Parasitol Res. 2012;110(1):235–43.

Liu GH, Gasser RB, Young ND, Song HQ, Ai L, Zhu XQ. Complete mitochondrial genomes of the 'intermediate form' of Fasciola and Fasciola gigantica, and their comparison with F. hepatica. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:150.

Wang X, Chen W, Huang Y, Sun J, Men J, Liu H, et al. The draft genome of the carcinogenic human liver fluke Clonorchis sinensis. Genome Biol. 2011;12(10):R107.

Takamiya S, Wang H, Hiraishi A, Yu Y, Hamajima F, Aoki T. Respiratory chain of the lung fluke Paragonimus westermani: facultative anaerobic mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;312(1):142–50.

Takamiya S, Fukuda K, Nakamura T, Aoki T, Sugiyama H. Paragonimus westermani possesses aerobic and anaerobic mitochondria in different tissues, adapting to fluctuating oxygen tension in microaerobic habitats. Int J Parasitol. 2010;40(14):1651–8.

Zarowiecki M, Berriman M. What helminth genomes have taught us about parasite evolution. Parasitology. 2015;142 Suppl 1:S85–97.

Hewitson JP, Grainger JR, Maizels RM. Helminth immunoregulation: the role of parasite secreted proteins in modulating host immunity. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2009;167(1):1–11.

Ju JW, Joo HN, Lee MR, Cho SH, Cheun HI, Kim JY, et al. Identification of a serodiagnostic antigen, legumain, by immunoproteomic analysis of excretory-secretory products of Clonorchis sinensis adult worms. Proteomics. 2009;9(11):3066–78.

Martinez-Sernandez V, Mezo M, Gonzalez-Warleta M, Perteguer MJ, Muino L, Guitian E, et al. The MF6p/FhHDM-1 major antigen secreted by the trematode parasite Fasciola hepatica is a heme-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(3):1441–56.

Yang SH, Park JO, Lee JH, Jeon BH, Kim WS, Kim SI, et al. Cloning and characterization of a new cysteine proteinase secreted by Paragonimus westermani adult worms. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71(1):87–92.

Cantacessi C, Mulvenna J, Young ND, Kasny M, Horak P, Aziz A, et al. A deep exploration of the transcriptome and "excretory/secretory" proteome of adult Fascioloides magna. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11(11):1340–53.

Liu F, Cui SJ, Hu W, Feng Z, Wang ZQ, Han ZG. Excretory/secretory proteome of the adult developmental stage of human blood fluke, Schistosoma japonicum. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8(6):1236–51.

Robinson MW, Menon R, Donnelly SM, Dalton JP, Ranganathan S. An integrated transcriptomics and proteomics analysis of the secretome of the helminth pathogen Fasciola hepatica: proteins associated with invasion and infection of the mammalian host. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8(8):1891–907.

Mulvenna J, Sripa B, Brindley PJ, Gorman J, Jones MK, Colgrave ML, et al. The secreted and surface proteomes of the adult stage of the carcinogenic human liver fluke Opisthorchis viverrini. Proteomics. 2010;10(5):1063–78.

Chung YB, Kita H, Shin MH. A 27 kDa cysteine protease secreted by newly excysted Paragonimus westermani metacercariae induces superoxide anion production and degranulation of human eosinophils. Korean J Parasitol. 2008;46(2):95–9.

Robinson MW, Corvo I, Jones PM, George AM, Padula MP, To J, et al. Collagenolytic activities of the major secreted cathepsin L peptidases involved in the virulence of the helminth pathogen, Fasciola hepatica. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(4):e1012.

Robinson MW, Dalton JP, Donnelly S. Helminth pathogen cathepsin proteases: it's a family affair. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33(12):601–8.

Smooker PM, Jayaraj R, Pike RN, Spithill TW. Cathepsin B proteases of flukes: the key to facilitating parasite control? Trends Parasitol. 2010;26(10):506–14.

Ludin P, Nilsson D, Maser P. Genome-wide identification of molecular mimicry candidates in parasites. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(3):e17546.

Blackman MJ, Ling IT, Nicholls SC, Holder AA. Proteolytic processing of the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 produces a membrane-bound fragment containing two epidermal growth factor-like domains. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;49(1):29–33.

Spiliotis M, Kroner A, Brehm K. Identification, molecular characterization and expression of the gene encoding the epidermal growth factor receptor orthologue from the fox-tapeworm Echinococcus multilocularis. Gene. 2003;323:57–65.

Vicogne J, Cailliau K, Tulasne D, Browaeys E, Yan YT, Fafeur V, et al. Conservation of epidermal growth factor receptor function in the human parasitic helminth Schistosoma mansoni. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(36):37407–14.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the McDonnell Genome Institute production team for assistance with RNA-Seq library construction and sequencing and John Martin for providing technical support.

Funding

Sequence generation and analysis was supported by NIH/NHGRI grants as part of ongoing food-borne trematode genome projects at the McDonnell Genome Institute and by a grant from the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation. The work in China was supported by the Open-End Fund for The Valuable and Precision Instruments of Central South University (CSUZC201539).

Availability of data and material

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in: (i) Additional files 2, 3, 4 and 5 (complete annotated transcriptome datasets, module counts and GO enrichment); (ii) The NCBI sequence read archive (raw reads; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) under BioProject ID PRJNA219632 for P. westermani (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/SRX1507710) and PRJNA301597 for P. skrjabini (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/SRX1507709), and (iii) Trematode.net (assembled transcripts and deduced protein sequences; http://trematode.net/TN_frontpage.cgi).

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: MM and BL. Performed the experiments: QRZ and KG. Analyzed the data: SNM, BAR and BL. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: BL, SNM, BAR, QRZ, KG, GJW and MM. Wrote the paper: BL, SNM and MM. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Dogs infected with P. westermani and P. skrjabini were maintained in the animal Facility of Xiang-Ya Medical College (Changsha, Hunan, People’s Republic of China). The Ethical Committee of Center for Parasitology Research (ECCPR) has approved all experimental procedures, including animal handling, under animal license number: syxk 125 2011-0001 and in accordance with strict ethical standards. The freshwater crabs Isolaptamon sp. for P. westermani and Sinopotamon denticulatum for P. skrjabini do not belong to the area of the country and Hunan Province which is an important wild animal conservation in China. Hence, the crab species collected are not considered endangered or rare according to the "Hunan Province Bureau of animal husbandry and Fisheries” and according to the wild animal conservation law (Article 24 issued on Aug. 28, 2004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Quality metrics for RNA samples used in the RNA-Seq experiment. Electrophoresis results and RIN graphs are included for (A) P. westermani and (B) P. skrjabini. (TIF 372 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Complete functional annotation and expression data for P. westermani transcripts. (XLSX 6726 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S2.

Complete functional annotation and expression data for P. skrjabini transcripts. (XLSX 7927 kb)

Additional file 4: Table S3.

KEGG module representation and completeness for P. westermani and P. skrjabini. (XLSX 49 kb)

Additional file 5: Table S4.

Gene Ontology term enrichment among transcript sets of interest from P. westermani and P. skrjabini. (XLSX 42 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Bw., McNulty, S.N., Rosa, B.A. et al. Conservation and diversification of the transcriptomes of adult Paragonimus westermani and P. skrjabini . Parasites Vectors 9, 497 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1785-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1785-x