Abstract

In the wake of the uprising global energy crisis, microalgae have emerged as an alternate feedstock for biofuel production. In addition, microalgae bear immense potential as bio-cell factories in terms of producing key chemicals, recombinant proteins, enzymes, lipid, hydrogen and alcohol. Abstraction of such high-value products (algal biorefinery approach) facilitates to make microalgae-based renewable energy an economically viable option. Synthetic biology is an emerging field that harmoniously blends science and engineering to help design and construct novel biological systems, with an aim to achieve rationally formulated objectives. However, resources and tools used for such nuclear manipulation, construction of synthetic gene network and genome-scale reconstruction of microalgae are limited. Herein, we present recent developments in the upcoming field of microalgae employed as a model system for synthetic biology applications and highlight the importance of genome-scale reconstruction models and kinetic models, to maximize the metabolic output by understanding the intricacies of algal growth. This review also examines the role played by microalgae as biorefineries, microalgal culture conditions and various operating parameters that need to be optimized to yield biofuel that can be economically competitive with fossil fuels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

An upsurge in global population coupled with rapid industrialization has tremendously increased worldwide per capita energy consumption. This rising energy demand is being fulfilled by various non-renewable energy sources, particularly fossil fuels. It is estimated that at the present usage, the worldwide demand for energy is envisaged to escalate by more than 50% by the year 2030 [1]. With a concomitant addition of 1.7 billion in the global population by 2050, the dwindling fossil fuel reserves will be subjected to further pressure [2]. The energy consumption rate for non-renewable sources such as natural petroleum is reported to be 105 times faster than the replenishment rate, which calls for an immediate attention to look for alternative, renewable and sustainable energy resources [1].

Biomass-derived biofuels are currently being considered as the most sustainable alternative to fossil fuels. Herein, problems such as water pollution and carbon dioxide emission associated with combustion of fossil fuels can be mitigated. Biofuels have been segregated into four generations based on their feedstock material [3,4,5]. Various cereals, sugarcane and oil-containing food crops constituted the feedstock for the first-generation biofuels. Sugar and starch-containing plants or cereal crops were used in the production of first-generation bioethanol. Production of bioethanol and methanol from low-cost crops, agricultural and forest residues (trees, straw, bagasse) constitutes the second-generation biofuel. The increased competition of crop-based first- and second-generation biofuels with food crops for arable land coupled with high corrosivity and hygroscopicity of bioethanol does not portray it to be an ideal candidate for replacement of fossil fuels. The third-generation biofuels exploit marine biomass such as seaweeds and algae for the generation of biofuels such as biogas, ethanol and butanol. Recent developments in synthetic and systems biology are paving the way for the fourth-generation biofuels, wherein specially engineered microorganism/crops will serve as feedstock material. Researchers are therefore, actively involved in developing alternative biofuel molecules, with structures similar to short-chain, branched-chain and cyclic alcohols, alkanes, alkenes, esters and aromatics.

Amongst various biomass, microalgae are gaining much attention for use as a potential feedstock by virtue of its high carbohydrate and lipid content, rapid growth rate and resistance to fluctuating environmental conditions [6]. Advancement in reverse engineering tools such as genome sequence, genetic transformation, gene targeting, different promoters, selection markers and molecular biology techniques such as clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR), transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs) and zinc-finger nucleases (ZFN) have paved the way to unravel novel metabolic pathways occurring within the algal cells or to design and synthesize new biological systems, all of which are aimed at furthering biofuel production [7,8,9,10]. Figure 1 illustrates the overall process involved in microalgae-based biofuel production. Recent studies conducted on model microalgae such as Chlamydomonas reinhardtii [11,12,13,14,15], Chlorella pyrenoidosa [16], Neodesmus sp. UTEX 2219-4 [17], Scenedesmus [18], Phaeodactylum tricornutum [19, 20], Dunaliella salina [21], Dunaliella parva [22], Nannochloropsis oceanic [23], Nannochloropsis salina [24], cyanobacteria [25] compliments the advances in molecular biology tools and facilitates to construct novel biological systems via synthetic biology. The present review deals with the recent developments in algal biorefinery, synthetic biology, metabolic engineering tools and the optimization of algal culture conditions through an algorithm, to address pressing issues related to algal biofuel production. This review also examines the role played by microalgae as biorefineries, microalgal culture conditions and various operating parameters that need to be optimized to yield biofuel that can be economically competitive with fossil fuels.

Products from algal biorefinery

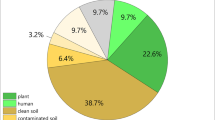

Development of microalgae-based biofuels in itself is not an economically competitive alternative to existing technologies and hence focus has now shifted towards abstraction of high-value co-products from microalgae to improve the economics of microalgae-based biorefinery. Biorefinery approach is a system where energy, fuel, chemicals and high-value products such as pigments, proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, vitamins and antioxidants are produced from biomass through various processes. Microalgae are rich in proteins, lipids and carbohydrates and the relative amounts of these biochemical components vary amongst various microalgal strains [26]. These could be used as feedstock for the production of various high-value bio-based products such as biodiesel production from microalgal lipids, alternate carbon source in the fermentation industries of microalgal carbohydrates, health food supplements from long-chain fatty acids found in microalgae and in pharmaceutical applications [27]. Recent studies conducted on microalgae for the production of various biofuels are listed in Table 1.

Variety of algal strains such as green alga C. reinhardtii, cyanobacteria Anabaena cylindrica and A. variabilis are well known for hydrogen production in the presence of sunlight. The aforementioned organisms are capable to extract and direct protons and electrons derived from water to hydrogen production, catalyzed via chloroplast hydrogenases, namely HydA1 and A2 (Hydrogenase) [28, 29]. Kruse et al. [28] observed that the native bio-hydrogen production rate in C. reinhardtii was improved (maximal rate of 4 mL/h) by inducing modification in its respiratory metabolism by eliminating potential competition for an electron with hydrogenase. Similarly, heterologous expression of hexose uptake protein (HUP1 hexose symporter from Chlorella kessleri) in a hydrogen-producing mutant (Stm6) of C. reinhardtii revealed approximately 150% increase in H2 production capacity [30]. With increased research focusing on third-generation biofuels, several recent studies on bioethanol production by employing algal strains such as Porphyridium cruentum [31], Tetraselmis suecica [32] and Desmodesmus sp. [33] have been reported. An algal strain Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 produced via double homologous recombination system was capable of photoautotrophically converting CO2 to bioethanol [34], with a maximum theoretical yield of 0.696 g ethanol/g CO2, as against 0.51 g ethanol/g glucose by S. cerevisiae. Active research needs to be directed in the field of algae-based bioethanol production, focusing on improvement in the yield to make the process economically viable.

Several recent studies indicated the production of bio-butanol from various microalgae such as carbohydrate-rich microalgae Neochloris aquatica CL-M1 [35], acid-pretreated biomass of Chlorella vulgaris JSC-6 [14] and microalgae-based biodiesel residues [36]. An algal strain, Synechococcus elongates, was reported to produce butanol synchronized with the production of isobutyraldehyde and isobutanol [37]. The genetically engineered S. elongates was able to produce isobutyraldehyde at a higher rate than those reported for ethanol, hydrogen or lipid production by either cyanobacteria or algae by the upregulation of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. The major obstacle in large-scale commercialization of microalgae-based bio-butanol is, however, the generation of several byproducts which reduces the purity and yield of pure butanol.

Biodiesel has emerged as a promising alternative for fossil fuels by virtue of having similar chemical characteristics with the latter. Most microalgae act as a resource for large-scale production of biodiesel owing to the high biomass productivity coupled with the rapid accumulation of lipid. Diverse algal genera such as Nannochloropsis, Dunaliella, Chaetoceros, Botryococcus, Scenedesmus and Pseudochlorococcum are known to accumulate high amount of neutral lipids [38,39,40]. The metabolic pathways of algal strains are able to produce 16–20 carbon fatty acids as precursors for the production of biodiesel. Nobre et al. [38] employed Nannochloropsis sp. for the production of fatty acid for biodiesel production and other co-products such as carotenoids and bio-hydrogen. This study reported that when CO2 supercritical fluid extraction was used, 45 g/100 g dry biomass of lipids and 70% of pigments were extracted. In a recent study, a high-lipid-producing microalga, namely Euglena sanguinea was investigated for biodiesel production [41]. The saturated fatty acids (C16:0, C18:0, C22:0, C24:0) and unsaturated fatty acids (C18:1) in the biodiesel confirmed that these could be potentially used in automobiles without any considerable transition in engine design. Here, systems biology, especially flux analysis, can provide an effective means of prediction by tracking the carbon flux during lipid accumulation, carbon fixation and growth altogether. The enzymes that can be targeted to enhance growth and carbon fixation can be determined from enzyme flux control coefficient data of Calvin cycle enzymes [42]. Likewise, the targets involved in lipid metabolism can also be found by 13C metabolic flux data and subsequent metabolic map derived from oleaginous algae. These flux data reveal which enzymes and the pathways they regulate are rate limiting and exert significant control over the larger metabolism [43, 44]. Nowadays, researchers are focusing on metabolic engineering pathways aimed at enhancing the fatty acid chain length, overexpression of genes involved in fatty acid synthesis with simultaneous down-regulation of genes involved in β-oxidation and lipase hydrolysis. These developments would facilitate to increase the yield, concurrent with an economical algal biodiesel production in the near future.

In addition to biofuels, microalgae are feedstock to several other high-value products such as vitamins, pigments, proteins, carbohydrates, amino acids, antioxidants, high-value long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) and biofertilizers. Natural microalgal pigments such as carotenoids, chlorophylls and phycobiliproteins serve as precursors of vitamins in food, pharmaceutical industries, cosmetics and coloring agents [45]. Several studies are focussing on microalgal genes encoding enzymes, which are involved in high-value carotenoid synthesis. Microalgae such as C. reinhardtii do not naturally synthesize ketocarotenoid, and β-carotene ketolase gene from Haematococcus pluvialis was expressed in C. reinhardtii to synthesize a new ketocarotenoid [46]. In another study, C. vulgaris was transformed with promoter and terminator of the nitrate reductase gene from P. tricornutum and the transgenic strain proved valuable for the production of value-added proteins [47]. Microalgae also serve as potential expression systems for the synthesis of biopolymers such as poly-3-hydroxybutyrate, which is a key precursor for the synthesis of biodegradable plastics. In a recent study, an ATP hydrolysis-based driving force module was engineered into Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 to produce 3-hydroxybutyrate [48]. The strain which was engineered by having a provision for a reversible outlet for excessive carbon flux was capable of producing significantly high amounts of 3-hydroxybutyrate over the native strain. Several microalgae secrete extracellular polymeric substances in their immediate living environment as a hydrated biofilm protective matrix [49]. These substances are known for high-value applications such as anti-inflammatories, antivirals, antioxidants, anticoagulants, biolubricants and drag reducers.

Spent microalgal biomass or lipid-extracted algal (LEA) biomass is an attractive feedstock for the production of various products as it contains 30–60% of residual carbon that is in the form of readily fermentable sugar [50]. In a recent study, LEA has been used as a substrate for biomethanation through anaerobic processes [51]. This study showed that the rate of biogas production was comparatively higher in product-extracted algal samples (lipid and protein extracted), whilst the cumulative methane production was higher for pretreated algae (dried powdered algae and heat-treated algae). A related study conducted by Hernández et al. [52] reported that anaerobic digestion of lipid-exhausted biomass showed higher yields of methane than non-lipid-exhausted biomass. LEA has also been used as raw material for butanol fermentation [53]. Bench-scale tests demonstrated that LEA could also be effectively converted to liquid fuel, mainly alkanes via hydrothermal liquefaction and upgrading processes such as via hydrotreating and hydrocracking. The overall energy efficiency on a higher heating value basis of this process was estimated to be 69.5% [54]. A study conducted by Gu et al. [55] demonstrated that Scenedesmusacutus was found to be capable of assimilating nitrogen from LEA residuals and was able to replace nitrate in culturing media, thus facilitating nutrient recycling. Another recent study reports that nitrogen/phosphorus limitation in microalgae leads to variation in lipid productivity, which was validated by the expression of acetyl-CoA carboxylase gene [25].

Bioprocesses for algal cultivation

Photosynthesis-dependent accumulation of biomass takes place under nitrogen-rich environment, whereas accumulation of lipids in microalgae occurs under stress conditions such as limited nutrient conditions. This contradiction hugely offsets continuous lipid production, thus affecting the economics of the system. The fed batch process has often been reported as the most suitable method for microalgal cultivation, because it offers the flexibility of customization of nutrients provided during the process. A study conducted by Zheng et al. [56] demonstrated that during the fed batch process, the lipid content and algal biomass were markedly increased. Moreover, studies proved that supply of light in phototrophic and mixotrophic processes during the fed batch culture increased the lipid productivity [57]. Light spectral quality also plays a key role in facilitating photosynthesis. Absorption of irradiation corresponding to the absorption band of the algal chlorophyll can lead to enhanced photosynthesis [58]. In a recent study, batch process was attempted in an open thin-layer cascade photobioreactor for high-cell density cultivation of a saline microalga (N. salina), wherein maximal cell density of 50 g/L was obtained within 25 days [59]. Similarly, fed batch heterotrophic microalgae cultivation of Auxenochlorella protothecoides was employed to maximize lipid production. An optimal feeding strategy was determined by interior point optimization [60]. On the contrary, Tang et al. [61] reported that long-term steady-state continuous process leads to significant lipid accumulation since the rate of dilution and irradiance can be regulated at specific levels. Furthermore, to maintain the steady state, the system is continuously being supplied with essential nutrients, which prevents the formation of inhibitory metabolites.

Although continuous feeding is required for maintenance of growth rate, the accompanying non-limiting nutrient supply may hamper accumulation of lipid and carbohydrates. To maintain a balance between lipid production and algal biomass production, a two-stage cultivation process was applied, wherein different set of conditions were supplied for growth and high lipid content/carbohydrate [62]. Thereafter, studies proved that semi-continuous strategy is most beneficial for algal biomass and lipid accumulation for longer periods because of the persistence of culture at exponential phase [63]. A recent study reported a two-stage continuous cultivation of Chlorella sp., where process variables such as dilution rate and feed stream substrate concentrations were optimized for biomass productivity and continuous production of lipid-rich algal biomass was monitored in two sequential bioreactors [64].

Under heterotrophic growth conditions, microalgae utilize a source of organic carbon as substrate for growth, which is converted to lipids. Due to the dependency on the availability of a continuous source of sugar, the cost of the process increases considerably. To overcome the aforementioned hurdles, microalgae are grown mixotrophically. Microalgae such as Chlorella sp. and Nannochloropsis sp. have been grown mixotrophically for consideration for biodiesel production [57]. In a comparative study between autotrophic, heterotrophic and mixotrophic cultivation, it was demonstrated that strains of microalgae Tribonema sp. showed enhanced growth in heterotrophic conditions, whereas lipid production was maximum during mixotrophic growth conditions [65]. Though several studies are focusing on these aspects, an effective microalgae-based system which does not compromise on growth or lipid content has not yet been developed.

Microalgae-based biofuel engineering

In addition to maintaining the right balance between the biomass content and lipid production, microalgae-derived biofuel faces several other challenges such as inefficient harvesting techniques and low productivity due to ineffective photobioreactor design and limited photosynthetic efficiency [66]. Genetic engineering tools aimed at overexpression of enzymes which are involved in lipid synthesis and storage and/or reduction of lipid catabolism mechanisms, offer a huge potential to engineer the required metabolisms. Figure 2 illustrates the interactions amongst various enzymes involved in the synthesis of lipids by algae. Over the years, research has been focused on overexpression of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase) involved in fatty acid synthesis and knocking out of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation (acyl CoA oxidase, acyl CoA synthase, carnitineacyltransferase I, fatty acyl CoA dehydrogenase) [17, 67]. Genetic manipulation in microalgae is challenging as editing tools are species specific and cannot be used interchangeably because of codon usage, defensive strategies (viz. restriction enzymes and methylation), uptake of nucleic acid and porosity of cells. Therefore, an extensive knowledge of the genetic construction of individual species is a prerequisite for customization of microalga for target biofuel production [68]. At present, there are a limited number of fully annotated genomes of microalgae available, but with improvements in sequencing techniques, rapid increase in such information is foreseeable in the near future.

Scheme representing the synergy between enzymes that lead to the formation of lipid (CA carbonic anhydrase; RuBisCO Ru1,5BP carboxylase/oxygenase; PDC pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; ACC acetyl-CoA carboxylase; KAS 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthase; ACL ATP-citrate lyase; MDH malate dehydrogenase; MME NADP-malic enzyme; PDC pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; GPAT glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase; LPAAT lyso-phosphatidic acid acyltransferase; LPAT lyso-phosphatidylcholine acyltransferase; DGAT diacylglycerol acyltransferase; PDAT phospholipid diacylglycerol acyltransferase

Synthetic biology in microalgae

The crux of synthetic biology is to be able to build artificial regulatory circuits that can control cellular behavior based on user-defined inputs/signals/stimuli to generate the desired output such as biofuel chemicals and proteins by making required changes in metabolism. The main focus of microalgal biotechnology for large-scale application of microalgae as a sustainable and robust energy feedstock is based on (a) improving their photosynthetic efficiency through metabolic engineering for improved oil yield and enhanced carbon sequestration rate in mass cultures, (b) driving the carbon flux into energy-rich compounds useful as biofuel source and (c) development of robust and committed algal cells that can sustain low-cost large-scale cultivation resulting in lower operational costs and lower carbon footprint of the produced chemical [69]. Synthetic biology functions by the construction of artificial biological systems by an amalgamation of engineering strategy with biotechnological tools, based on the genetic, metabolic and regulatory data gathered from experiments [69, 70]. In simple words, it is the field of biology which focuses on reconstruction or re-engineering the metabolic pathways with the introduction of genetic modules and which are observed as “biological circuits’’. The objective is to reprogram microalgae to derive a novel function. The reconstruction of relevant biochemical pathways (that yield metabolite of importance) into partial or total synthetic alternatives needs a stable assembly along with the integration of heterologous DNA segments into hosts or chassis strains. The various ways genes can be fabricated for reconstructions are (a) ligation and digestion of DNA fragments, (b) in vitro homologous recombination of fragments and (c) in vivo homologous recombination [59].

Elements of synthetic circuits/biobricks

In a bid to commercialize transgenic microalgae, certain challenges need to be addressed. These are primarily poorly developed molecular tools for genetic engineering and low level of heterologous gene expression from the nucleus [69, 71]. With the advent of novel genomic tools, synthetic biology is fast developing and the concept of “BioBricks” could be introduced in microalgal systems. These biobricks are standardized DNA segments having common interface, which can be assembled into biological systems. Such parts are interchangeable units such as promoters [72,73,74], terminators, ribosome-binding sites (RBS), trans-elements and various regulatory molecules that can be used to regulate genetics of microalgae and ultimately their metabolism [75]. In addition to the aforementioned genetic tools, “omics” approach could play a vital role in structuring pathway reconstruction in microalgae by helping us understand the metabolism in the whole system, which is regulated through feedback-forward and -backward loops that affect the output. The huge amount of available ‘omics’ data could also be channeled towards attaining lipid-inducing conditions (i.e., stress stimulus), thus leading to an efficient regulation of metabolism via application of synthetic biology by targeting the regulatory networks rather than mere deletion or overexpression of enzyme-coding genes [76,77,78,79].

Microalgal context

Synthetic biology could be presently applied to systems with reverse genetic tools and have developed resources such as genomic sequence, selection markers, plasmid vectors, various promoters and genetic editing tools. However, these are presently being limited to selected microalgal species. The microalgal models that can be congenial to reverse genetics and synthetic biology perturbations based on the existing genetic resources are available for C. reinhardtii, Nannochloropsis sp., P. tricornutum, Cyanidioschyzon merolae, Ostreococcus tauri and Thalassiosira pseudonana [70]. Traditionally, most of the applications of synthetic biology have been carried out in a model microalga, C. reinhardtii, where existing tools are being modified and optimized, synchronous with the development of novel tools. Therefore, in C. reinhardtii, protein production has been accomplished by engineering the chloroplast genome because reverse genetics and editing methods could be attempted in chloroplasts. With the development of expression constructs [80, 81], protein production has been recorded to reach 80 times more in chloroplasts than that of nuclear expression [82, 83]. Attempts have been made to alter the algal photosynthetic machinery by synthetic biology via expression of heterologous genes (gene psbA that codes D1 subunit of Photo system II) in chloroplasts as “Biobricks” under the influence of endogenous regulatory system [84]. Efforts have also been carried out to engineer Rubisco under varying external environment, to enable optimized utilization of energy and carbon. This was carried out by altering the amount of rbcl mRNA (large subunit genes of Arabidopsis Rubsico) maturation factor MRL1 from the nuclear genome of MRL1-deficient mutant. Rubisco content has been reported to reduce by 15% in comparison with the wild type, with no reduction observed in their growth. Interestingly, in the presence of inducible promoters, Rubisco amount could be altered under varying light intensity and CO2 concentration, as shown by Johnson [85]. Key events that mark the development of synthetic biology in microalgae-based oil accumulation are illustrated in Fig. 3.

Lipid metabolism is highly complex and tightly regulated with an elaborate regulatory network of nodes and internodes. Hence, the characterization of pathways with an extensive knowledge about carbon sharing is imperative for fabrication of artificial pathways. Investigations have been carried out to observe carbon partitioning between starch and lipid and attempts have been made to isolate the key players of triacylglycerol (TAG) formation under stress in C. reinhardtii [86]. Lipid engineering has been carried out in microalgae with an aim to produce TAG with better cold flow properties, making them a better feedstock amenable for biodiesel production. In diatom P. tricornutum, the ratio of short-chain fatty acids C12 and C14 were increased by enhanced expression of thioesterases derived from different plants [87]. Similar efforts have been carried out in C. reinhardtii wherein the fatty acid profile has been engineered for better fuel properties [82]. A recent study reported the production of a wide range of degree of unsaturation in TAG (designer oils) by rational modulation of type II diacyl glycerol acyltransferases in Nannochloropsis oceanica via reverse genetics [88].

In a typical synthetic circuit, three components are present—sensors (which sense the external inputs), processors (that process the signal and determine them) and actuators (that transmit the signal downstream which make required changes in the cell). In biological systems, regulatory circuits are mainly governed by transcriptional, post-transcriptional and post-translational components such as regulatory molecules, cis-elements, noncoding RNAs and transcription factors [69, 70]. In an effort to better understand the promoter structure for augmenting the nuclear gene expression, Scranton et al. [89] developed 25 synthetic algal promoters (sap) in C. reinhardtii by mimicking their native cis-elements, structure and sequences of highly expressing genes. Some of these synthetic promoters performed better than the best endogenous promoter hsp70/rbs2, thus opening new potentials for exploring the C. reinhardtii system through synthetic strategies [89]. Most of the synthetic circuits used the principle of transcriptional control that needs effective (can control the target gene expression to desired level) and programmable (can carry out functions at any desired loci) transcription factors which do not involve in cross talk.

These features ideally place newly discovered CRISPR/Cas (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR associated) and CRISPR–Cpf1 system as effective means to design synthetic TFs for complex synthetic gene circuits. Versatility of CRISPR/Cas system in gene regulation such as multiplex regulation (to modulate several genes simultaneously), orthogonality (ability to avoid cross talk among several regulatory modules), bi-directionality (simultaneous activation and repression of different genes) and complex activation/regulation [90, 91] using CRISPR variants has been demonstrated in several systems such as algae [14, 92], plants [93, 94], yeasts and mammals [95, 96].

Applications of CRISPR

CRISPR has proven to be an effective and popular strategy for exploring complex regulatory synthetic circuits [97]. In mammalian cells, synthetic biology has been demonstrated in two independent studies where the output upstream of a cascade becomes the input for a downstream module—a basic display of synthetic circuit. Here, a gRNA along with dCas9 influenced the expression of another gRNA downstream in a circuit that ultimately controls a fluorescent protein as an observable output of a final task [98, 99]. More advanced circuits such as logic gates utilizing CRISPR have also been explored in bladder cancer cells and E. coli. In bladder cells, dCas9 and gRNA were expressed under promoters which are cancer cell (hTERT) and bladder cell specific (hUPII). The CRISPR/dCas9 was expressed against a lacI repressor, whose repression relieved the expression of transgene therapeutic proteins, i.e., the output of the circuit [100]. The output of the circuit was only possible in bladder cancer cells when both promoters were active, which resembles an AND gate of an electric circuit. In E. coli model system, a gRNA is driven by an inducible promoter, which if expressed recruits a dCas9 to bind the constitutive promoter of a gene referred as ‘output’, thus, sterically hindering the RNA polymerase to bind and generate the output in the presence of an input signal. Output is, therefore, possible in the absence of input signal molecule, i.e., a NOT gate approach is observed [101]. The gRNA could also be expressed from two different inducible promoters each induced by different input signals. Thus, the output can be observed only when neither of the inducers are present, i.e., a NOR gate. Similarly with modifications, OR and AND gates can be constructed synthetically, thus exploring the possibility of more logical operations in a cell.

These concepts inspired from other systems could be utilized and attempted in microalgae and cyanobacteria through their inducible promoters/repressors, as discussed in Table 2 to build complex programmable synthetic circuits to produce products of value such as lipids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, proteins, alcohols and chemicals. Moreover, several recent studies have successfully attempted CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering, enabling researchers to utilize this strategy in microalgal systems [14, 92, 102, 103]. Inducible circuits can be built in microalgae as well, with the help of inducible promoters giving inputs for driving gRNA [47, 104, 105] and light-inducible promoters activating dCas9 [106], especially because light being a known inducer of lipid synthesis helps in biofuel production (Fig. 4). A synthetic chromosome technology for microalgae was proposed by Keasling and Venter [107] for the creation of an algal platform for coordinated and controllable metabolic modifications, which would act as a designer synthetic cell committed to desired higher value product. Innovations carried out in the creation of a synthetic bacterial cell may open new horizons for microalgae synthetic biology [108]. Thus, synthetic strategies could be fully explored in various products of importance from microalgae such as lipid, bio-hydrogen, fatty acids and recombinant proteins.

Hypothetical circuits proposed with the help of genetic modules (plasmids a, b, c) that can be applied to microalgae with light intensity stimulus. Case 1. Input (plasmid a + b) = light-inducible promoter::gRNA for transcription factor (PSR1/NRR1)a + light-inducible promoter::dCas9/VP64(CRISPRa) = activation of lipid pathway (Output). Case 2. Input (plasmid a + c) = light-inducible promoter::gRNA for transcription factor (Zn(II)2Cys6)b + light-inducible promoter::dCas9/SRDX(CRISPRi) = inactivation of lipid pathway suppressors (Output). aPSR1 and NRR1 are transcription factors that get induced during stress which leads to lipid accumulation [171, 172]. bZn(II)2Cys6 is a transcription factor that negatively regulates lipid accumulation under nitrogen stress [183]

Synthetic biology not only facilitates the researchers to alter or modify metabolic pathway/s but also reprograms the cells by inserting metabolic pathways of interest. Here, the pathway of interest could be taken from one organism and inserted into another, to follow the enzymatic potential [109]. This rewiring of heterogeneous pathways into a host system leads to the creation of new metabolic networks, which induces phenotypes of interest by shifting the cell’s precedence from growth in targeted production, hence enabling construction of effective cell factories. Such insertions have been successfully performed to induce synthesis of precursors of diverse biofuel molecules, including 1-butanol [110], 2-methyl-1-butanol [111], acetone [112], ethylene [113], isoprene [73] and fatty acids [114]. The aforementioned studies clearly portray the potential role of synthetic pathways in the field of improvement of algal biofuel. The development of computational tools such as ‘pathway prediction system’ (PPS) further facilitates pathway synthesis aimed at various applications: biofuel production, degradation of xenobiotic compounds, etc. [115]. Different algorithms such as BNICE algorithm (Biochemical Network Integrated Computational Explorer) [116] and ReBiT (Retro-Biosynthesis Tool) [117] have been developed to assist in enzyme identification, thus furthering design of diverse pathways.

Genome-scale metabolic reconstruction

Genome-scale metabolic reconstruction is an in silico technique, which utilizes biochemical models to predict microorganisms’ response to various genetic or environmental stresses. To save time and to make the method economically feasible, this method is slowly emerging as an alternate to wet lab experiments. Metabolic engineering has enabled custom designing and production of novel molecules, bearing desirable properties for wide-scale commercial, environmental and healthcare applications. Genome-scale reconstruction of an organism accurately predicts chemical transformations taking place within cellular components and focuses on delineating genetic networks governing biochemical pathways that are industrially desirable [70, 118, 119]. Classic examples of genome-scale metabolic reconstruction of N. salina and Nannochloropsis gaditana portray the importance of such in silico techniques to predict metabolic capabilities of various microalgae [120, 121]. Advances in genetics and bioinformatic tools led the way towards manipulating microalgae, envisioning improvements in light utilization, carbon flow manipulation and lipid engineering [71]. This knowledge is a powerful tool, facilitating control of strains to produce molecules of interest. With the aid of genome sequence and biochemical information, the genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are used to depict the absolute metabolic reactions and pathways and association between gene and protein reactions (GPR).

For the reconstruction of a novel or a less studied species, GEMs would require the entire known biochemical data and system wide data obtained through omics analyses. Progress in metabolic engineering studies and the data generated from such studies have depicted the importance of GEMs in designing new strains. Dal’Molin et al. [122] constructed a GEM (named AlgaGEM) based on the genomic sequence of C. reinhardtii. AlgaGEM is a complete literature-based GEM which reports the functions of 866 unique ORFs, 1862 metabolites, 2249 gene–enzyme reaction association entries and 1725 unique reactions. It was reconstructed using available compartmentalization data of cytoplasm, mitochondrion, plastid and microbody algae and compartmentalization data of Arabidopsis thaliana. Primarily, AlgaGEM portrays a functional metabolism for Chlamydomonas and anticipates distinct algal behavior. This model was validated by simulating the growth and metabolic functions obtained from the literature [122]. Chang et al. [123] reconstructed a genome-scale metabolic network for the same microalga (C. reinhardtii) and devised a modeling approach which predicts growth for a given light source, resolving wavelength and photon flux. They experimentally verified the transcripts, which were investigated in the network and physiologically validated model function showing high confidence in network contents and predictive applications.

A similar compartmentalized GEM was reconstructed for Chlorella variabilis by employing 526 genes, 1236 metabolites and 1455 reactions. This model was effective in apprehending growth of C. variabilis under various light conditions and facilitated analysis of metabolic pathway for the synthesis of chitosan and rhamnose. This reconstructed model will aid in providing useful information regarding target metabolites and allow improved features in the strain by metabolic engineering [124]. Yang et al. [125] proposed such a reconstruction model for a eukaryotic microalga C. pyrenoidosa. This model included two compartments and consisted of 61 metabolites and 67 metabolic reactions, wherein the influence of carbon and energy metabolism under various trophic modes were explained by the use of metabolic flux analysis. Metabolic reconstruction modeling combined with real-time PCR and RNA-Seq gene expression data was employed to gain an insight into mechanisms that lead to rapid TAG accumulation in Tetraselmis sp. M8, as the cells transitioned from a growth phase to stationary phase [126]. This study demonstrated a distinct early-stationary phase, which was distinguished by reduced cell division and increased lipid accumulation. The subsequent stationary phase was characterized by a cessation of cell division and a significant lipid accumulation. A summary of studies incorporating metabolic flux analysis has been depicted in Table 3.

The major constraint after getting a fully annotated sequence is that it is not possible to fully predict the metabolic capabilities of the species. This leads to the construction of metabolic models, which predict probable biochemical pathways in an organism. Species-specific networks are created based on evidences from their gene–protein associations. The information about enzymes such as EC numbers, gene, protein, pathways and substrates is linked with the help of protein databases and its resources, viz. BRENDA [69] and ExPASy [25]. Visualization is an excellent approach for deeper understanding of pathways and reconstructed metabolic networks. Metabolites are represented as nodes and interactions are denoted using edges in metabolic networks. There are various web-based visualization tools for metabolic pathways, viz. BioCyc, MetaCyc, [69, 118] and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [17, 43, 118]. Cytoscape [77, 127, 128] is a biological network visualization and data integration tool used for visualization of the results from FBA studies [130]. CytoSEED [129] is a Cytoscape plug-in that is utilized for visualizing results from the Model SEED [69]. Fluxviz [130] is Cytoscape plug-in to visualize the flux distribution in the molecular interaction network. VANTED [131] is another data visualization and data integration tool, which could be utilized as a standalone tool. For the visualization of GEMs, a new tool has been recently developed called MetDraw [132]. This tool is compatible with systems biology markup language (SBML) file inputs and allows export of the map image as SVG files. It also grants visualization of reaction fluxes added to gene–protein expression data and metabolomics and projects all on the reconstructed network map.

Designing predictive gene regulatory network model

Gene regulatory networks describe the complex mat of transcription factors that bind to regulatory sequences of target genes for the expression of function [133]. Gene regulatory networks (GRNs) are used to portray regulation between the genetic entities for the final expression. Computational modeling of GRNs [134] can add additional confirmation to support the wet lab findings. The sequences for transcriptional-factor-binding sites can be obtained from databases such as TRANSFAC and PROSITE, or using similarity search tools using genomic sequence. However, there is very little number of known regulatory regions. Research now focuses on developing algorithms for regulatory regions. MEME program35 is one of the popular algorithms that search for motifs in nucleotide and protein sequences that occur more often than would be predicted by chance. However, selection of the input sequence is highly sensitive.

Optimum cultivation using response surface method and genetic algorithm

There are several practical limitations in scaling up of laboratory-based algal biomass cultivation to commercial scale, economic non-feasibility being one of the major factors, as reviewed in detail by Slade and Bauen [135]. However, the cost of algal biomass can be reduced appreciably via enhanced biomass productivity and reduction in specific nutrient consumption through well-designed and optimized production system. This calls for an accelerated algal biomass production with complete recycling of the culture medium, which can be achieved by process optimization. Figure 5 summarizes multi-objective optimal cultivation strategies for microalgae. Several studies have reported improvement in algal growth through better media formulations and selecting optimum algal cultivation variables.

Algal regression models based on statistical approach and biokinetic models based on algal growth mechanism are popularly used for optimal algal cultivation. Central composite design (CCD) and response surface methodology (RSM) are tools to optimize operating conditions such as algal biomass productivity (YBM), lipid yield (Ylipid) or CO2 uptake (\( Y_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }} \)) from the selected design of experiments (DOEs). In general, quadratic response models are approximated to fit experimental responses in DOEs. Therefore, the responses such asYBM, Ylipid and \( Y_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }} \) are usually represented by second-order polynomial equations with multiple variables. The best performing algal regression model is selected on the basis of analysis of variance (ANOVA) criteria. The model with low standard deviation, high R-squared values (i.e., R2, adjusted R2 and predicted R2) and low predicted residual error sum of squares (PRESS) are selected for analysis. A gradient-based numerical search technique is employed for optimization of the selected model.

The Design-Expert software is popularly used for the development of regression model and graphical optimization. The parameters most commonly employed in algal cultivation and lipid accumulation are nutrient loading and environmental stress, including temperature, light intensity, salt and pH [136, 137]. Light intensity and the loading of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and their mutual interactions are the factors which primarily influence productivity in Dunaliella tertiolecta, whereas stress due to NaCl and light–NaCl interactions were found to significantly influence the lipid accumulation [138]. Similar effects of nutrients and environmental parameters were observed for the cultivation of Nannochloropsis sp., wherein algal biomass growth, lipid and eicosapentaenoic acid productivity were maximized [139]. A general observation was that enhanced lipid accumulation occurred under nutrient limitation and stressed environmental conditions. In contrast, algal growth was reduced significantly under these stressed conditions. Algal biomass and lipid productivity-involved trade-off could be handled efficiently using elitist non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm, namely NSGA-II [8, 137, 139]. Although, CCD-RSM-based model is employed to predict algal biomass productivity and lipid accumulation in algal cells; this method fails to depict the parametric effects without relating the growth kinetics. In addition, CCD-RSM model has been found to be applicable under laboratory scale only and difficult to implement under pilot/commercial scales. Therefore, one should rely on the optimum cultivation results, which are obtained on the basis of mechanistic biokinetic models for the prediction of growth behavior of microalgae.

The classical Monod/Andrews models for nutrient adsorption and Droop model involving intercellular nutrient quota are also used to predict the algal growth behavior. The rate of absorption of nutrients (e.g., N and/or P) are often influenced by the bulk concentration of nutrients (N, P, K and C) as well as NaCl concentration, which are taken care by the Monod model at the low substrate loading and Andrews inhibition model at high substrate loading.

Algal growth is also induced by the internal nutrient cell quota (i.e., N and/or P), which is described by Droop model \( \left[ {{\text{i}}.{\text{e}}., \, \, \propto \left( {1 - \frac{{q_{{0,{\text{S}}}} }}{{q_{\text{S}} }}} \right)} \right] \), where q0,S is the minimum allowable cell quota for N or P and qS is the time variant internal quota in cell. Haldane inhibition model \( \left[ { \propto \left( {\frac{{I_{\text{avg}} }}{{K_{\text{L}} + I_{\text{avg}} + \frac{{I_{\text{avg}}^{2} }}{{K_{\text{IL}} }}}}} \right)} \right] \) is commonly used to account for light-induced algal growth, where Iavg is the average algal medium light intensity, KL and KIL are light half-saturation and inhibition constants, respectively. Temperature-induced growth was usually taken care by incorporating Arrhenius activation \( \left( {{\text{i}}.{\text{e}}., \propto {\text{e}}^{{ - \frac{{\Delta E_{\text{a}} }}{\text{RT}}}} } \right) \) and inactivation \( \left( {{\text{i}}.{\text{e}}., \propto {\text{e}}^{{\frac{{\Delta E_{\text{d}} }}{\text{RT}}}} } \right) \) function in growth equation. Temperature-dependent growth could also be expressed by an empirical equation given by \( \sqrt \mu = b\left( {T - T_{ \hbox{min} } } \right)\left\{ {1 - { \exp }\left[ {c\left( {T - T_{ \hbox{max} } } \right)} \right]} \right\} \) where μ is the specific algal growth rate, Tmin and Tmax are the allowable minimum and maximum temperatures for algal growth, and b and c are constants. Lee et al. [140] reviewed algal growth kinetics under different nutrient and environmental stress conditions. In a recent study, Kumar et al. proposed a detailed algal kinetics based on Monod/Andrews and Droop model to predict algal biomass growth, nutrient cell quota and lipid production [119]. Sinha et al. [141] carried out multi-objective optimization involving minimization of cultivation cost and maximization of algal biomass and lipid productivities simultaneously using NSGA-II algorithm with inheritance. It was observed that nonlinear light intensity and temperature trajectory helped to improve algal biomass productivity and cell lipid accumulation with the reduction in cultivation cost. Therefore, one can find the best possible control strategy for cost-effective accelerated biomass growth and lipid accumulation by solving multi-objective optimization problems including scale-up studies. Selection of the best combination of environmental parameters such as nutrient requirements (nitrogen, phosphorous, potassium, carbon), salinity, temperature, culture age, initial population, pH, photoperiod and light intensity significantly affects algal biomass. The response surface method and genetic algorithm are not directly related to the generation of biofuels from microalgae. However, these optimization techniques are crucial for the formulation of optimum conditions governing algal biomass growth as well as lipid production and, therefore, need to be carefully considered while designing and constructing novel microalgal systems.

Conclusions

Microalgae bear immense potential as bio-cell factories in terms of producing key chemicals, recombinant proteins, enzymes, lipid, hydrogen, alcohol etc. Abstraction of such high-value products (algal biorefinery approach) facilitates to make microalgae-based renewable energy as an economically viable option. Synthetic biology is an emerging field that harmoniously blends science and engineering to help design and construct novel biological systems, with an aim to achieve rationally formulated objectives. The microbial genetic information, which is easily amenable to modification via metabolic engineering, systems biology and pathway reconstruction coupled with synthetic biology, allows researchers to produce required biomolecules. However, resources and tools used for such nuclear manipulation, construction of synthetic gene network and genome-scale reconstruction of microalgae are limited. The use of synthetic biology in algal biofuel production is still in its infancy, wherein challenges in the development of more advanced genetic tools, high biomass and improved CO2 fixation capacity need to be resolved. In addition to the aforementioned, novel consolidated bioprocess wherein a single microbe can generate renewable biofuel as an alternative to depleting fossil fuels is the need of the hour. This review also examines the role played by microalgae as biorefineries, microalgal culture conditions and various operating parameters that need to be optimized to yield biofuel that can be economically competitive with fossil fuels.

To summarize, algal biorefinery in the present state strategically produces multiple products—bulk and specialized co-product to increase the total revenue from cultivation and make the bulk production economically feasible. In practice, multiproduct large-scale biorefinery still poses several problems, which need to be soon addressed. Some economically important value-added products such as astaxanthin and oil; lutein and oil; EPA and oil are being produced in lab scale. Attempts should be made to facilitate their large-scale production through proper pathway prediction and growth and metabolic modeling, wherein the domains of systems biology and process optimization will play a crucial role. Process optimization can lead us to optimized combination of growth conditions such as light, temperature, mass transfer, reactor configuration, media formulation and supplementation, which produces improved growth kinetics. Systems biology, on the other hand, can aid in optimal use of carbon and energy balance so that every possible carbon atom is put to use and every ATP is spent judiciously taking into account the metabolism, physiology and induced stress response. This can fructify only when channeling metabolic flux and partitioning are efficient, both of which are predicted by reconstructed genome-scale metabolic models. These in silico models are based on systems biology data that stem from omics and labeling analysis.

Abbreviations

- CRISPR:

-

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- TALEs:

-

transcription activator-like effectors

- ZFN:

-

zinc-finger nucleases

- LEA:

-

lipid-extracted algal

- RBS:

-

ribosome-binding sites

- TAG:

-

triacylglycerol

- CRISPR/Cas:

-

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR associated

- PPS:

-

pathway prediction system

- BNICE:

-

Biochemical Network Integrated Computational Explorer

- ReBiT:

-

Retro-Biosynthesis Tool

- GEM:

-

genome-scale metabolic model

- GPR:

-

gene–protein reactions

- PGDB:

-

Pathway Genome Database

- ExPaSy:

-

Expert Protein Analysis System

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- SBML:

-

Systems Biology Markup Language

- GRNs:

-

gene regulatory networks

- CCD:

-

central composite design

- RSM:

-

response surface methodology

- DOEs:

-

design of experiments

- ANOVA:

-

analysis of variance

- PRESS:

-

predicted residual error sum of squares

References

Shuba ES, Kifle D. Microalgae to biofuels: ‘promising’alternative and renewable energy, review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2018;81:743–55.

Oey M, Sawyer AL, Ross IL, Hankamer B. Challenges and opportunities for hydrogen production from microalgae. Plant Biotechnol J. 2016;14(7):1487–99.

Acheampong M, Ertem FC, Kappler B, Neubauer P. In pursuit of sustainable development goal (SDG) number 7: will biofuels be reliable? Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;75:927–37.

Gaurav N, Sivasankari S, Kiran GS, Ninawe A, Selvin J. Utilization of bioresources for sustainable biofuels: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;73:205–14.

Ahmad AL, Yasin NHM, Derek CJC, Lim JK. Microalgae as a sustainable energy source for biodiesel production: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2011;15:584–93.

Chisti Y. Biodiesel from microalgae. Biotechnol Adv. 2007;25:294–306.

Banerjee C, Agrawal HK, Singh PK, Bandopadhyay R, Shukla P. Proteomic approaches in microalgal research: challenges and opportunities. In: Hameed S, editor. Contemporary issues in biotechnology: progress and applications. New Delhi: Astral International; 2015.

Banerjee C, Singh PK, Shukla P. Microalgal bioengineering for sustainable energy development: recent transgenesis and metabolic engineering strategies. Biotechnol J. 2016;11:303–14.

Banerjee C, Dubey KK, Shukla P. Metabolic engineering of microalgal based biofuel production: prospects and challenges. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1–8.

Anand V, Singh PK, Banerjee C, Shukla P. Proteomic approaches in microalgae: perspectives and applications. 3 Biotech. 2017;7:197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-017-0831-5.

Kao PH, Ng S. CRISPRi mediated phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase regulation to enhance the production of lipid in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Bioresour Technol. 2017;245:1527–37.

Anderson MS, Muff TJ, Georgianna DR, Mayfield SP. Towards a synthetic nuclear transcription system in green algae: characterization of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii nuclear transcription factors and identification of targeted promoters. Algal Res. 2017;22:47–55.

Chen B, Lee K, Plucinak T, Duanmu D, Wang Y, Horken KM, Weeks DP, Spalding MH. A novel activation domain is essential for CIA5-mediated gene regulation in response to CO2 changes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Algal Res. 2017;24:207–17.

Wang Q, Lu Y, Xin Y, Wei L, Huang S, Xu J. Genome editing of model oleaginous microalgae Nannochloropsis spp. by CRISPR/Cas9. Plant J. 2016;88:1071–81.

Bertalan I, Munder MC, Weiβ C, Kopf J, Fischer D, Johanningmeier U. A rapid modular and marker-free chloroplast expression system for the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Biotechnol. 2015;195:60–6.

Fan J, Xu H, Li Y. Transcriptome-based global analysis of gene expression in response to carbon dioxide deprivation in the green algae Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Algal Res. 2016;16:12–9.

Chang WC, Zheng HQ, Chen CNN. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals a potential photosynthate partitioning mechanism between lipid and starch biosynthetic pathways in green microalgae. Algal Res. 2016;16:54–62.

Sharma T, Gour RS, Kant A, Chauhan RS. Lipid content in Scenedesmus species correlates with multiple genes of fatty acid and triacylglycerol biosynthetic pathways. Algal Res. 2015;12:341–9.

Seo S, Jeon H, Hwang S, Jin ES, Chang KS. Development of a new constitutive expression system for the transformation of the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Algal Res. 2015;11:50–4.

Shemesh Z, Leu S, Goldberg IK, Cohen SD, Zarka A, Boussiba S. Inducible expression of Haematococcus oil globule protein in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum: association with lipid droplets and enhancement of TAG accumulation under nitrogen starvation. Algal Res. 2016;18:321–31.

Simon DP, Anila N, Gayathri K, Sarada R. Heterologous expression of β-carotene hydroxylase in Dunaliella salina by Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation. Algal Res. 2016;18:257–65.

Shang C, Bi G, Yuan Z, Wang Z, Alam MA, Xie J. Discovery of genes for production of biofuels through transcriptome sequencing of Dunaliella parva. Algal Res. 2016;13:318–26.

Kaye Y, Grundman O, Leu S, Zarka A, Zorin B, Cohen SD, Goldberg IK, Boussiba S. Metabolic engineering toward enhanced LC-PUFA biosynthesis in Nannochloropsis oceanica: overexpression of endogenous Δ12 desaturase driven by stress-inducible promoter leads to enhanced deposition of polyunsaturated fatty acids in TAG. Algal Res. 2015;11:387–98.

Kang NK, Choi GG, Kim EK, Shin SE, Jeon S, Park MS, Jeong KJ, Jeong BR, Chang YK, Yang JW, Lee B. Heterologous overexpression of sfCherry fluorescent protein in Nannochloropsis salina. Biotechnol Rep. 2015;8:10–5.

Kumar R, Biswas K, Singh PK, Singh PK, Elumalai S, Shukla P, Pabbi S. Lipid production and molecular dynamics simulation for regulation of accD gene in cyanobacteria under different N and P regimes. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2017;10:94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-017-0776-2.

Suganya T, Varman M, Masjuki HH, Renganathan S. Macroalgae and microalgae as a potential source for commercial applications along with biofuels production: a biorefinery approach. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2016;55:909–41.

Chng LM, Lee KT, Chan DJC. Synergistic effect of pretreatment and fermentation process on carbohydrate-rich Scenedesmus dimorphus for bioethanol production. Energy Convers Manag. 2017;141:410–9.

Kruse O, Rupprecht J, Bader KP, Hall ST, Schenk PM, Finazzi G, Hankamer B. Improved photo biological H2 production in engineered green algal cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:34170–7.

Imam J, Singh PK, Shukla P. Biohydrogen as biofuel: future prospects and avenues for improvements. In: Gupta VK, Tuohy MG, editors. Biofuel technologies. Berlin: Springer; 2013. p. 301–15.

Doebbe A, Rupprecht J, Beckmann J, Mussgnug JH, Hallmann A, Hankamer B, Kruse O. Functional integration of the HUP1 hexose symporter gene into the genome of C. reinhardtii: impacts on biological H2 production. J Biotechnol. 2007;131:27–33.

Kim HM, Oh CH, Bae HJ. Comparison of red microalgae (Porphyridium cruentum) culture conditions for bioethanol production. Bioresour Technol. 2017;233:44–50.

Reyimu Z, Ozçimen D. Batch cultivation of marine microalgae Nannochloropsis oculata and Tetraselmis suecica in treated municipal wastewater toward bioethanol production. J Clean Prod. 2017;150:40–6.

Rizza LS, Smachetti MES, Nascimento MD, Salerno GL, Curatti L. Bioprospecting for native microalgae as an alternative source of sugars for the production of bioethanol. Algal Res. 2017;22:140–7.

Dexter J, Fu P. Metabolic engineering of cyanobacteria for ethanol production. Energy Environ Sci. 2009;2:857–64.

Wang Y, Ho SH, Cheng CL, Nagarajan D, Guo WQ, Lin C, Li S, Ren N, Chang JS. Nutrients and COD removal of swine wastewater with an isolated microalgal strain Neochloris aquatica CL-M1 accumulating high carbohydrate content used for bio butanol production. Bioresour Technol. 2017;242:7–14.

Cheng HH, Whang LM, Chan KC, Chung MC, Wu SH, Liu CP, Tien SY, Chen SY, Chang JS, Lee WJ. Biological butanol production from microalgae-based biodiesel residues by Clostridium acetobutylicum. Bioresour Technol. 2015;184:379–85.

Atsumi S, Higashide W, Liao JC. Direct photosynthetic recycling of carbon dioxide to isobutyraldehyde. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:1177–80.

Nobre BP, Villalobos F, Barragán BE, Oliveira AC, Batista AP, Marques PASS, Mendes RL, Sovová H, Palavra AF, Gouveia L. A biorefinery from Nannochloropsis sp. microalga-extraction of oils and pigments. Production of biohydrogen from the left over biomass. Bioresour Technol. 2013;135:128–36.

Qunju H, Wenzhou X, Shikun D, Tao L, Fangfang Y, Qikun J, Guanghua W, Hualian W. The influence of cultivation period on growth and biodiesel properties of microalga Nannochloropsis gaditana 1049. Bioresour Technol. 2015;192:157–64.

Abomohra AE, Jin W, El-Sheekh M. Enhancement of lipid extraction for improved biodiesel recovery from the biodiesel promising microalga Scenedesmus obliquus. Energy Convers Manag. 2016;108:23–9.

Kings AJ, Raj RE, Miriam LRM, Visvanathan MA. Cultivation, extraction and optimization of biodiesel production from potential microalgae Euglena sanguinea using eco-friendly natural catalyst. Energy Convers Manag. 2017;141:224–35.

Yang B, Liu J, Ma X, Guo B, Liu B, Wu T, Jiang Y, Chen F. Genetic engineering of the Calvin cycle toward enhanced photosynthetic CO2 fixation in microalgae. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2017;10:229.

Wu C, Xiong W, Dai J, Wu Q. Genome-based metabolic mapping and 13C flux analysis reveal systematic properties of an oleaginous microalga Chlorella protothecoides. Plant Physiol. 2015;167(2):586–99.

Allen DK. Assessing compartmentalized flux in lipid metabolism with isotopes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1861(9):1226–42.

Chew KW, Yap JY, Show PL, Suan NH, Juan JC, Ling TC, Lee DJ, Chang JS. Microalgae biorefinery: high value products perspectives. Bioresour Technol. 2017;229:53–62.

Vila M, Galván A, Fernández E, León R. Ketocarotenoid biosynthesis in transgenic microalgae expressing a foreign β-C-4-carotene oxygenase gene. In: Barredo JL, editor. Microbial carotenoids from bacteria and microalgae. Methods in molecular biology, vol. 892. Totowa: Humana Press; 2012.

Niu YF, Zhang MH, Xie WH, Li JN, Gao YF, Yang WD, Liu JS, Li HY. A new inducible expression system in a transformed green alga, Chlorella vulgaris. Genet Mol Res. 2011;10(4):3427–34.

Ku JT, Lan EI. A balanced ATP driving force module for enhancing photosynthetic biosynthesis of 3-hydroxybutyrate from CO2. Metab Eng. 2018;46:35–42.

Xiao R, Zheng Y. Overview of microalgal extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and their applications. Biotechnol Adv. 2016;34(7):1225–44.

Rashid N, Rehman MSU, Han JI. Recycling and reuse of spent microalgal biomass for sustainable biofuels. Biochem Eng J. 2013;75:101–7.

Ansari FA, Wahal S, Gupta SK, Rawat I, Bux F. A comparative study on biochemical methane potential of algal substrates: implications of biomass pre-treatment and product extraction. Bioresour Technol. 2017;234:320–6.

Hernández D, Solana M, Riaño B, García- González MC, Bertucco A. Biofuels from microalgae: lipid extraction and methane production from the residual biomass in a biorefinery approach. Bioresour Technol. 2014;170:370–8.

Gao K, Orr V, Rehmann L. Butanol fermentation from microalgae-derived carbohydrates after ionic liquid extraction. Bioresour Technol. 2016;206:77–85.

Zhu Y, Albrecht KO, Elliott DC, Hallen RT, Jones SB. Development of hydrothermal liquefaction and upgrading technologies for lipid-extracted algae conversion to liquid fuels. Algal Res. 2013;2(4):455–64.

Gu H, Nagle N, Pienkos PT, Posewitz MC. Nitrogen recycling from fuel-extracted algal biomass: residuals as the sole nitrogen source for culturing Scenedesmus acutus. Bioresour Technol. 2015;184:153–60.

Zheng Y, Li T, Yu X, Bates PD, Dong T, Chen S. High-density fed-batch culture of a thermotolerant microalga Chlorella sorokiniana for biofuel production. Appl Energy. 2013;108:281–7.

Cheirsilp B, Torpee S. Enhanced growth and lipid production of microalgae under mixotrophic culture condition: effect of light intensity, glucose concentration and fed-batch cultivation. Bioresour Technol. 2012;110:510–6.

Ra CH, Kang CH, Jung JH, Jeong GT, Kim SK. Enhanced biomass production and lipid accumulation of Picochlorum atomus using light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Bioresour Technol. 2016;218:1279–83.

Apel AC, Pfaffinger CE, Basedahl N, Mittwollen N, Gobel J, Sauter J, Brück T, Weuster-Botz D. Open thin-layer cascade reactors for saline microalgae production evaluated in a physically simulated Mediterranean summer climate. Algal Res. 2017;25:381–90.

Abdollahi J, Dubljevic S. Lipid production optimization and optimal control of heterotrophic microalgae fed-batch bioreactor. Chem Eng Sci. 2012;84:619–27.

Tang H, Chen M, Ng KYS, Salley SO. Continuous microalgae cultivation in a photobioreactor. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109(10):2468–74.

Ho SH, Chen WM, Chang JS. Scenedesmus obliquus CNW-N as a potential candidate for CO2 mitigation and biodiesel production. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101(22):8725–30.

Ho SH, Kondo A, Hasunuma T, Chang JS. Engineering strategies for improving the CO2 fixation and carbohydrate productivity of Scenedesmus obliquus CNW-N used for bioethanol fermentation. Bioresour Technol. 2013;143:163–71.

Palabhanvi B, Muthuraj M, Kumar V, Mukherjee M, Ahlawat S, Das D. Continuous cultivation of lipid rich microalga Chlorella sp. FC2 IITG for improved biodiesel productivity via control variable optimization and substrate driven pH control. Bioresour Technol. 2017;224:481–9.

Wang H, Zhou W, Shao H, Liu T. A comparative analysis of biomass and lipid content in five Tribonema sp. strains at autotrophic, heterotrophic and mixotrophic cultivation. Algal Res. 2017;24:284–9.

Chen CY, Yeh KL, Aisyah R, Lee DJ, Chang JS. Cultivation, photobioreactor design and harvesting of microalgae for biodiesel production: a critical review. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102(1):71–81.

Liang MH, Jiang JG. Advancing oleaginous microorganisms to produce lipid via metabolic engineering technology. Prog Lipid Res. 2013;52(4):395–408.

Banerjee A, Banerjee C, Negi S, Chang JS, Shukla P. Improvements in algal lipid production: a systems biology and gene editing approach. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2018;38(3):369–85.

Singh R, Mattam AJ, Jutur P, Yazdani SS. Synthetic biology in biofuels production. Rev Cell Biol Mol Med. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/3527600906.mcb.201600003.

Hlavova M, Turoczy Z, Bisova K. Improving microalgae for biotechnology: from genetics to synthetic biology. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33(6):1194–203.

Gimpel JA, Mayfield SP. Analysis of heterologous regulatory and coding regions in algal chloroplasts. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97(10):4499–510.

Niederholtmeyer H, Wolfstädter BT, Savage DF, Silver PA, Way JC. Engineering cyanobacteria to synthesize and export hydrophilic products. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76(11):3462–6.

Lindberg P, Park S, Melis A. Engineering a platform for photosynthetic isoprene production in cyanobacteria using Synechocystis as the model organism. Metab Eng. 2010;12(1):70–9.

Kunert A, Vinnemeier J, Erdmann N, Hagemann M. Repression by fur is not the main mechanism controlling the iron-inducible isiAB operon in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;227(2):255–62.

Berla BM, Saha R, Immethun CM, Maranas CD, Moon TS, Pakrasi H. Synthetic biology of cyanobacteria: unique challenges and opportunities. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:246.

Park JJ, Wang H, Gargouri M, Deshpande RR, Skepper JN, Holguin FO, Juergens MT, Shachar-Hill Y, Hicks LM, Gang DR. The response of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii to nitrogen deprivation: a systems biology analysis. Plant J. 2015;81(4):611–24.

Gargouri M, Park JJ, Holguin FO, Kim MJ, Wang H, Deshpande RR, Shachar-Hill Y, Hicks LM, Gang DR. Identification of regulatory network hubs that control lipid metabolism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Exp Bot. 2015;66(15):4551–66.

Hu J, Wang D, Li J, Jing G, Ning K, Xu J. Genome-wide identification of transcription factors and transcription-factor binding sites in oleaginous microalgae Nannochloropsis. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5454.

Banerjee A, Maiti SK, Guria C, Banerjee C. Metabolic pathways for lipid synthesis under nitrogen stress in Chlamydomonas and Nannochloropsis. Biotechnol Lett. 2017;39(1):1–11.

Coragliotti AT, Beligni MV, Franklin SE, Mayfield SP. Molecular factors affecting the accumulation of recombinant proteins in the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii chloroplast. Mol Biotechnol. 2011;48(1):60–75.

Rasala BA, Mayfield SP. Photosynthetic biomanufacturing in green algae; production of recombinant proteins for industrial, nutritional, and medical uses. Photosynth Res. 2015;123(3):227–39.

Gong Y, Hu H, Gao Y, Xu X, Gao H. Microalgae as platforms for production of recombinant proteins and valuable compounds: progress and prospects. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;38(12):1879–90.

Rasala BA, Chao SS, Pier M, Barrera DJ, Mayfield SP. Enhanced genetic tools for engineering multigene traits into green algae. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e94028.

Gimpel JA, Specht EA, Georgianna DR, Mayfield SP. Advances in microalgae engineering and synthetic biology applications for biofuel production. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17(3):489–95.

Johnson X. Manipulating RuBisCO accumulation in the green alga, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;76(3–5):397–405.

Goncalves EC, Wilkie AC, Kirst M, Rathinasabapathi B. Metabolic regulation of triacylglycerol accumulation in the green algae: identification of potential targets for engineering to improve oil yield. Plant Biotechnol J. 2016;14(8):1649–60.

Radakovits R, Eduafo PM, Posewitz MC. Genetic engineering of fatty acid chain length in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Metab Eng. 2011;13(1):89–95.

Xin Y, Lu Y, Lee YY, Wei L, Jia J, Wang Q, Wang D, Bai F, Hu H, Hu Q, Liu J, Li Y, Xu J. Producing designer oils in industrial microalgae by rational modulation of co-evolving Type-2 diacylglycerol acyltransferases. Mol Plant. 2017;10(12):1523–39.

Scranton MA, Ostrand JT, Georgianna DR, Lofgren SM, Li D, Ellis RC, Carruthers DN, Dräger A, Masica DL, Mayfield SP. Synthetic promoters capable of driving robust nuclear gene expression in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Algal Res. 2016;15:135–42.

Zalatan JG, Lee ME, Almeida R, Gilbert LA, Whitehead EH, Russa ML, Tsai JC, Weissman JS, Dueber JE, Qi LS, Lim WA. Engineering complex synthetic transcriptional programs with CRISPR RNA scaffolds. Cell. 2015;160(1–2):339–50.

Konermann S, Brigham MD, Trevino AE, Joung J, Abudayyeh OO, Barcena C, Hsu PD, Habib N, Gootenberg JS, Nishimasu H, Nureki O, Zhang F. Genome-scale transcriptional activation by an engineered CRISPR-Cas9 complex. Nature. 2015;517(7536):583–8.

Nymark M, Sharma AK, Sparstad T, Bones AM, Winge P. A CRISPR/Cas9 system adapted for gene editing in marine algae. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24951.

Ma X, Zhang Q, Zhu Q, Liu W, Chen Y, Qiu R, Wang B, Yang Z, Li H, Lin Y, Xie Y, Shen R, Chen S, Wang Z, Chen Y, Guo J, Chen L, Zhao X, Dong Z, Liu YG. A robust CRISPR/Cas9 system for convenient, high-efficiency multiplex genome editing in monocot and dicot plants. Mol Plant. 2015;8(8):1274–84.

Li JF, Norville JE, Aach J, McCormack M, Zhang D, Bush J, Church GM, Sheen J. Multiplex and homologous recombination-mediated genome editing in Arabidopsis and Nicotiana benthamiana using guide RNA and Cas9. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(8):688–91.

Bortesi L, Fischer R. The CRISPR/Cas9 system for plant genome editing and beyond. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33(1):41–52.

Gupta SK, Shukla P. Gene editing for cell engineering: trends and applications. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2017;37(5):672–84.

Jusiak B, Cleto S, Piñera PP, Lu TK. Engineering synthetic gene circuits in living cells with CRISPR technology. Trends Biotechnol. 2016;34(7):535–47.

Nissim L, Perli SD, Fridkin A, Perez-Pinera P, Lu TK. Multiplexed and programmable regulation of gene networks with an integrated RNA and CRISPR/Cas toolkit in human cells. Mol Cell. 2014;54(4):698–710.

Kiani S, Beal J, Ebrahimkhani MR, Huh J, Hall RN, Xie Z, Li Y, Weiss R. CRISPR transcriptional repression devices and layered circuits in mammalian cells. Nat Methods. 2014;11(7):723–6.

Liu Y, Zeng Y, Liu L, Zhuang C, Fu X, Huang W, Cai Z. Synthesizing AND gate genetic circuits based on CRISPR-Cas9 for identification of bladder cancer cells. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5393.

Nielsen AA, Voigt CA. Multi-input CRISPR/Cas genetic circuits that interface host regulatory networks. Mol Syst Biol. 2014;10(11):763.

Jiang W, Brueggeman AJ, Horken KM, Plucinak TM, Weeks DP. Successful transient expression of Cas9 and single guide RNA genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eukaryot Cell. 2014;13(11):1465–9.

Shin SE, Lim JM, Koh HG, Kim EK, Kang NK, Jeon S, Kwon S, Shin WS, Lee B, Hwangbo K, Kim J, Ye SH, Yun JY, Seo H, Oh HM, Kim KJ, Kim JS, Jeong WJ, Chang YK, Jeong BR. CRISPR/Cas9-induced knockout and knock-in mutations in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27810.

Schmollinger S, Strenkert D, Schroda M. An inducible artificial microRNA system for Chlamydomonas reinhardtii confirms a key role for heat shock factor 1 in regulating thermo tolerance. Curr Genet. 2010;56(4):383–9.

Niu YF, Yang ZK, Zhang MH, Zhu CC, Yang WD, Liu JS, Li HY. Transformation of diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum by electroporation and establishment of inducible selection marker. Biotechniques. 2012;52(6):1–3.

Blankenship JE, Kindle KL. Expression of chimeric genes by the light-regulated cabII-1 promoter in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: a cabII-1/nit1 gene functions as a dominant selectable marker in a nit1-nit2-strain. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12(11):5268–79.

Keasling JD, Venter JC. Applications of synthetic biology to enhance life. Bridge. 2013;43(3):47–58.

Gibson DG, Glass JI, Lartigue C, Noskov VN, Chuang RY, Algire MA, Benders GA, Montague MG, Ma L, Moodie MM, Merryman C, Vashee S, Kumar RK, Garcia NA, Andrews-Pfannkoch C, Denisova EA, Young L, Qi ZQ, Segall-Shapiro TH, Calvey CH, Parmar PP, Hutchison CA III, Smith HO, Venter JC. Creation of a bacterial cell controlled by a chemically synthesized genome. Science. 2010;329(5987):52–6.

Wheeldon I, Christopher P, Blanch H. Integration of heterogeneous and biochemical catalysis for production of fuels and chemicals from biomass. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2017;45:127–35.

Lan EI, Liao JC. ATP drives direct photosynthetic production of 1-butanol in cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(16):6018–23.

Shen CR, Liao JC. Photosynthetic production of 2-methyl-1-butanol from CO2 in cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942 and characterization of the native acetohydroxyacid synthase. Energy Environ Sci. 2012;5(11):9574–83.

Zhou J, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Li Y, Ma Y. Designing and creating a modularized synthetic pathway in cyanobacterium Synechocystis enables production of acetone from carbon dioxide. Metab Eng. 2012;14(4):394–400.

Takahama K, Matsuoka M, Nagahama K, Ogawa T. Construction and analysis of a recombinant cyanobacterium expressing a chromosomally inserted gene for an ethylene-forming enzyme at the psbAI locus. J Biosci Bioeng. 2003;95(3):302–5.

Liu X, Sheng J, Curtiss R. Fatty acid production in genetically modified cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(17):6899–904.

Hou BK, Ellis LBM, Wackett LP. Encoding microbial metabolic logic: predicting biodegradation. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;31(6):261–72.

Hatzimanikatis V, Li C, Ionita JA, Henry CS, Jankowski MD, Broadbelt LJ. Exploring the diversity of complex metabolic networks. BMC Bioinform. 2005;21(8):1603–9.

Prather KLJ, Martin CH. De novo biosynthetic pathways: rational design of microbial chemical factories. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19(5):468–74.

Bhowmick G, Koduru L, Sen R. Metabolic pathway engineering towards enhancing microalgal lipid biosynthesis for biofuel application—a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2015;50:1239–53.

Kumar A, Guria C, Chitres G, Chakraborty A, Pathak AK. Modelling of microalgal growth and lipid production in Dunaliella tertiolecta using nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium fertilizer medium in sintered disk chromatographic glass bubble column. Bioresour Technol. 2016;218:1021–36.

Loira N, Mendoza S, Cortés MP, Rojas N, Travisany D, Di Genova A, Gajardo N, Ehrenfeld N, Maass A. Reconstruction of the microalga Nannochloropsis salina genome-scale metabolic model with applications to lipid production. BMC Syst Biol. 2017;11(1):66.

Shah AR, Ahmad A, Srivastava S, Ali BMJ. Reconstruction and analysis of a genome-scale metabolic model of Nannochloropsis gaditana. Algal Res. 2017;26:354–64.

de Oliveira Dal’Molin CG, Quek LE, Palfreyman RW, Nielsen LK. AlgaGEM—a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction of algae based on the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii genome. BMC Genomics. 2011;12(4):S5.

Chang RL, Ghamsari L, Manichaikul A, Hom EFY, Balaji S, Fu W, Shen Y, Hao T, Palsson B, Ashtiani KS, Papin JA. Metabolic network reconstruction of Chlamydomonas offers insight into light-driven algal metabolism. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7(1):518.

Juneja A, Chaplen FWR, Murthy GS. Genome scale metabolic reconstruction of Chlorella variabilis for exploring its metabolic potential for biofuels. Bioresour Technol. 2016;213:103–10.

Yang C, Hua Q, Shimizu K. Energetics and carbon metabolism during growth of microalgal cells under photoautotrophic, mixotrophic and cyclic light autotrophic/dark-heterotrophic conditions. Biochem Eng J. 2000;6(2):87–102.

Lim DKY, Schuhmann H, Hall SRT, Chan KCK, Wass TJ, Aguilera F, Adarme-Vega TC, Dal’Molin CGO, Thorpe GJ, Batley J, Edwards D, Schenk PM. RNA-Seq and metabolic flux analysis of Tetraselmis sp. M8 during nitrogen starvation reveals a two-stage lipid accumulation mechanism. Bioresour Technol. 2017;244(2):1281–93.

Smoot ME, Ono K, Ruscheinski J, Wang PL, Ideker T. Cytoscape 2.8: new features for data integration and network visualization. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(3):431–2.

Saito R, Smoot ME, Ono K, Ruscheinski J, Wang PL, Lotia S, Pico AR, Bader GD, Ideker T. A travel guide to Cytoscape plugins. Nat Methods. 2012;9:1069–76.

DeJongh M, Bockstege B, Frybarger P, Hazekamp N, Kammeraad J, McGeehan T. CytoSEED: a Cytoscape plugin for viewing, manipulating and analysing metabolic models created by the model SEED. BMC Bioinform. 2012;28(6):891–2.

Konig M, Holzhutter HG. Flux viz-cytoscape plug-in for visualization of flux distributions in networks. Genome Inform. 2012;24:96–103.