Abstract

Background

Pretreatment is necessary to reduce biomass recalcitrance and enhance the efficiency of enzymatic saccharification for biofuel production. Ionic liquid (IL) pretreatment has gained a significant interest as a pretreatment process that can reduce cellulose crystallinity and remove lignin, key factors that govern enzyme accessibility. There are several challenges that need to be addressed for IL pretreatment to become viable for commercialization, including IL cost and recyclability. In addition, it is unclear whether ILs can maintain process performance when utilizing low-cost, low-quality biomass feedstocks such as the paper fraction of municipal solid waste (MSW), which are readily available in high quantities. One approach to potentially reduce IL cost is to use a blend of ILs at different concentrations in aqueous mixtures. Herein, we describe 14 IL-water systems with mixtures of 1-ethyl-3-ethylimidazolium acetate ([C2C1Im][OAc]), 1-butyl-3-ethylimidazolium acetate ([C4C1Im][OAc]), and water that were used to pretreat MSW blended with agave bagasse (AGB). The detailed analysis of IL recycling in terms of sugar yields of pretreated biomass and IL stability was examined.

Results

Both biomass types (AGB and MSW) were efficiently disrupted by IL pretreatment. The pretreatment efficiency of [C2C1Im][OAc] and [C4C1Im][OAc] decreased when mixed with water above 40%. The AGB/MSW (1:1) blend demonstrated a glucan conversion of 94.1 and 83.0% using IL systems with ~10 and ~40% water content, respectively. Chemical structures of fresh ILs and recycle ILs presented strong similarities observed by FTIR and 1H-NMR spectroscopy. The glucan and xylan hydrolysis yields obtained from recycled IL exhibited a slight decrease in pretreatment efficiency (less than 10% in terms of hydrolysis yields compared to that of fresh IL), and a decrease in cellulose crystallinity was observed.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrated that mixing ILs such as [C2C1Im][OAc] and [C4C1Im][OAc] and blending the paper fraction of MSW with agricultural residues, such as AGB, may contribute to lower the production costs while maintaining high sugar yields. Recycled IL-water mixtures provided comparable results to that of fresh ILs. Both of these results offer the potential of reducing the production costs of sugars and biofuels at biorefineries as compared to more conventional IL conversion technologies.

Schematic of ionic liquid (IL) pretreatment of agave bagasse (AB) and paper-rich fraction of municipal solid waste (MSW)

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Liquid transportation fuels and value-added products can be obtained from renewable sources such as grasses and agricultural or forestry residues due to their naturally high carbohydrate content. Moreover, these lignocellulosic biomass materials are available at significant levels and can achieve high sugar production with minimal impact on food sources when compared to first-generation technologies [1]. A pretreatment step is a necessary prerequisite to increase biomass digestibility by reducing its recalcitrance. After this stage, pretreated materials are enzymatically digested into fermentable sugars that are then suitable for biofuel and/or renewable chemical production using fermentation [2]. Various biomass pretreatment technologies have been developed with the general objective to alter or remove hemicellulose and/or lignin, increase surface area and/or decrease the crystallinity of cellulose [3].

In recent years, numerous studies have shown that imidazolium-based ionic liquids (ILs) are attractive as green solvents for biomass pretreatment due to several traits, including high cellulose solubility, low vapor pressure, chemical and thermal stability, non-flammability, and phase behavior. These ILs are relatively benign to the environment when compared to pretreatments that use acids, bases, and/or organic solvents. After IL pretreatment, cellulose can be easily recovered by the addition of an antisolvent, such as water or ethanol [4, 5]. In addition, ionic liquids have been used in the dissolution and partial delignification of corn stover, switchgrass, agave bagasse, softwood, hardwood, and municipal solid waste (MSW) [6–11].

Although IL pretreatment leads to enhanced biomass saccharification, the biggest challenge for commercialization of this technology lies in the relatively high cost of ILs, which can range from $1 up to $800/kg, depending on the purity and source, making it essential to develop comprehensive strategies for improving the overall economics of the biorefineries using IL pretreatment platform [12]. To address the high-cost issue of ILs, we have taken four different approaches into consideration.

The first approach entails the use of MSW (which paper mix represents 30% of total) as a lower quality feedstock; therefore by blending a paper-rich fraction of MSW with a higher quality feedstock overall costs can be reduced in a biorefinery scheme [9, 13]. Currently, most biomass conversion studies have focused on the conversion of a single feedstock with little consideration on feedstock diversity and mixed feedstocks. Moreover, biomass availability varies significantly from region to region due to weather conditions and crop varieties and increase the need for a biorefinery that can effectively and efficiently process mixed feedstocks [14, 15].

A second approach for improving the economics of IL pretreatment involves the utilization of aqueous solutions of ILs as opposed to a typical process that uses 100% IL. These aqueous mixtures have significantly lowered viscosities relative to neat ILs, making handling easier and enhancing mass transfer. Previous findings have shown that selected ILs can act effectively in the presence of water, enhancing glucan digestibility due to competitive hydrogen bonding [16–20]. Decreasing IL use without decreasing sugar yields will be reflected in final production costs.

A third approach used to minimize associated costs with using ILs to pretreat biomass is to employ ILs combination of acetate (anion) and imidazolium (cation) such as [C2C1Im][OAc] and [C4C1Im][OAc] which demonstrate high lignin removal and cellulose decrystallization in studies where their specific interactions and performance were examined [7, 11, 21, 22].

Imidazolium-based ILs typically have numerous advantages in biomass biorefineries including pretreatment performance independent of biomass type, moderate reaction values (time and temperature), and compatibility with pretreatment reactor construction materials [23]. Currently, [C4C1Im][OAc] costs about 80% when compared to [C2C1Im][OAc], which can lead to reduced costs if pretreatment performance can be maintained.

Finally, a fourth approach concerns the recyclability and reusability of ILs for several consecutive batches, which will likely be required for commercial use as a biomass pretreatment within a biorefinery. Recycling of ILs would occur after the addition of an antisolvent such as water that precipitates cellulose and allows easy recovery through filtration or centrifugation. A number of reports have studied the recovery and recycling of ILs after biomass pretreatment with different conditions and equipment [24–26], addition of kosmotropic anions (such as phosphate carbonate and sulfate) to form aqueous biphasic systems [27, 28] and from a technoeconomic perspective [29]. Nevertheless, the particular effects on the recycled ILs and its impact on biomass pretreatment have not been completely elucidated.

This study aims to assess the effect of a ternary aqueous system by mixing [C2C1Im][OAc], [C4C1Im][OAc], and water at 14 selected ratios for the pretreatment of a 1:1 blend of MSW and agave bagasse (AGB) (Fig. 1). AGB was selected to be blended with MSW due to favorable characteristics as a bioenergy feedstock such as high carbohydrate content, low water inputs, and high productivities in semiarid regions as well as previous studies that demonstrated high sugar yields can be obtained after IL pretreatment [8]. In order to better understand the pretreatment process, changes in chemical structure were examined by Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, 1H NMR, and component characterization. We also examined the effects of recycling [C2C1Im][OAc] and [C4C1Im][OAc] three times on pretreatment performance. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report that employs a mixture of ILs and water for the pretreatment of mixed feedstock blends.

Methods

Materials and preparation

For the MSW, paper waste materials were prepared as in [9], consisting of 15% glossy paper, 25% non-glossy paper, 32% non-glossy cardboard, and 28% glossy cardboard using a process developed by Idaho National Laboratory (INL). It is recognized that this material is not representative of real MSW streams and that there may be contaminants present that will impact pretreatment effectiveness. However, the goal of this study was to examine the effectiveness of the IL systems in this study on the types of paper that would be found in MSW. Destiladora Rubio, a tequila plant from Jalisco, Mexico, donated the AGB. The AGB was milled with a Thomas-Wiley Mini Mill fitted with a 40-mesh screen (Model 3383-L10 Arthur H. Thomas Co., Philadelphia, PA, USA). Both ground biomass samples were stored at 4 °C in a sealed plastic bag prior to their use. The 1:1 blend was prepared by mixing both MSW and AGB in the pretreatment reactor just before the heating process begins. 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate [C2C1Im][OAc] and 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate [C4C1Im][OAc], citric acid, ethanol, glucose, xylose, sulfuric acid, and HPLC grade water were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich.

Aqueous ionic liquid pretreatment in tube reactors

A design of experiments was carried out using Minitab® software (Coventry, UK), utilizing 14 unique aqueous ionic liquid combinations (ranked in cost decreasing order), composed of two ionic liquid: [C2C1Im][OAc] and [C4C1Im][OAc] plus DI water (constrained up to 50% when combined with ILs) at different ratios (Fig. 1). One gram of biomass (dry basis) was mixed with 9 g of the specific ternary aqueous IL solution to give a 10% (w/w) biomass solution. The biomass was loaded in tubular reactors made of 0.75-in diameter × 6-in length Hastelloy (C276) tubes, which were then sealed with stainless steel caps. All pretreatment procedures were run in triplicate in tubular reactors that were heated to reaction temperature (120 °C) for 3 h in a WVR convection oven [8]. After pretreatment, all reactors were quenched by quickly transferring them to a room temperature water bath until the temperature dropped to 30 °C, followed by a washing step performed as previously described [30]. A total of 42 experiments were carried out, where the recovered product was lyophilized for two days in a FreeZone12 (Labconco, MO, USA) equipment before compositional analysis.

Recycle of ionic liquid and pretreatment

The IL/water mixtures obtained from the pretreatments in tube reactors with pure [C2C1Im][OAc] and [C4C1Im][OAc] in AGB were evaporated at 100 °C for 12 h in a drying oven to remove excess water, and then reused to pretreat AGB in tube reactors at 120 °C and 3 h at ambient pressure without any further purification. A total of 3 cycles were performed where the solution of each IL was again separated, concentrated, and reused. The recycling pretreatments were conducted in duplicate and the IL/biomass mixture was homogenized using a glass rod. A portion of the recovered biomass on each cycle was stored for compositional analysis and other one was used for enzymatic saccharification. For each IL recycle, 500 µL was withdrawn to analyze their integrity by FTIR and 1H-NMR.

Chemical characterization

Sugars content of untreated and pretreated biomass samples were determined according to the standard analytical procedures of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) LAP 017 using a two-step acid hydrolysis method [31]. Briefly, for all samples, 0.3 g of dry biomass was treated with 3 mL of 72% H2SO4 for 60 min at 30 °C with constant agitation, then diluted with 84 mL of DI water, finally autoclaved at 121 °C for 1 h. The content of acid insoluble lignin (referred to as lignin in the rest of the manuscript) was determined gravimetrically as the solid residue remaining after two-step hydrolysis. The liquid filtrates were used to determine the carbohydrate concentrations by Agilent HPLC 1200 series equipped with a Bio-Rad Aminex HPX-87H column and a refractive index detector.

Delignification was calculated using the following equation:

Enzymatic saccharification

Saccharification of all biomass samples was carried out at 55 °C and 150 rpm for 72 h in 50 mM citrate buffer (pH 4.8) in a rotary incubator with commercial enzyme cocktails, Cellic® CTec2 and HTec2, obtained as a gift from Novozymes. The protein content of enzymes was determined by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay with a Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific) using BSA as protein standard. CTec2 has a protein content of 186.6 ± 2.0 mg/mL, and protein content of HTec2 was 180.1 ± 1.8 mg/mL. The enzyme activity of CTec2 was determined to be ~80 filter paper units (FPU)/mL. The enzyme loading was normalized to the glucan content (5 g/L) present in the biomass samples to understand the impact of each pretreatment in the response variable of sugar production. Hence, the enzyme concentration of CTec2 and HTec2 was set constant at 20 mg protein/g glucan and 2 mg protein/g xylan, respectively. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Analysis of saccharified samples

Sugars concentrations were monitored using HPLC by taking 50 µL of the saccharification supernatant. The samples were filtered in 0.45 µm Pall 96-well filter plate, centrifuged (4000 rpm—5 min), recollected in a 96-well Bio-Rad plate and finally covered with pierceable aluminum foil (to prevent vapor losses) to monitored glucose and xylose production in all samples by an Agilent HPLC 1200 series equipped with a Bio-Rad Aminex HPX-87H column and a refractive index detector. The glucan conversion was calculated using

and is based on the mass of each material used before pretreatment, thus representing an overall process conversion. The xylan conversion was calculated using

and is based on the difference in molecular weight between xylan and the xylose unit [32].

Attenuated total reflectance (ATR)-FTIR spectroscopy

ATR-FTIR was conducted using a Bruker Optics Vertex system with built-in diamond-germanium ATR single reflection crystal. All samples were pressed uniformly against the diamond surface using a spring-loaded anvil. Sample spectra were obtained in triplicates using an average of 128 scans over the range between 800 and 2000 cm−1 with a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1. Air, water, and the appropriate IL solution were used as background for untreated and pretreated biomass samples, respectively. Baseline correction was conducted using the rubber band method following the spectrum minima [5].

Crystallinity measurement

XRD diffractogram of untreated and IL-treated AGB with fresh and recycled ILs ([C2C1Im][OAc] and [C4C1Im][OAc]) in AGB were acquired with a PANalytical Empyrean diffractometer equipped with a PIXcel3D detector with Cu Kα radiation. The samples were scanned in the range of 5–50° (2θ) with a step size of 0.026° at 45 kV and 40 mA under ambient temperature. Crystallinity index (CrI) was calculated by using Eq. (4) [33]

where I 002 is the intensity for the crystalline portion of biomass at about 2θ = 22.4, and I am is the peak for the amorphous portion at 2θ = 16.6.

Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectroscopy

1H NMR spectra of fresh and recycled ILs were acquired at 25 °C using a Bruker DRX-500 MHz instrument equipped with a Z-gradient inverse TXI 1H/13C/15N 5 mm probe (ns = 128 and d1 = 10.0 s). Chemical shifts were referenced to tetramethylsilane. The NMR spectra were processed using Bruker’s Topspin 3.1 (Windows) processing software.

Statistical analysis

The software Minitab 17 was used for analysis of variance (ANOVA) of experimental results. A 5% probability level (p = 0.05) was used to accept or reject the null hypothesis of significant differences. Duncan’s multiple range test at the level of 5% was used to analyze the significances of glucan and xylan conversion of the pretreated biomass besides delignification and glucan conversion of the effect of using recycled ILs [34].

Results and discussion

Compositional analysis of untreated and pretreated biomass

The initial step to decrease biomass recalcitrance towards fermentable sugars, this is to pretreat the feedstock for downstream processing (saccharification and fermentation). Previous studies have found that [C2C1Im][OAc] is an effective solvent to solubilize AGB bagasse plant cell wall, regenerating cellulose while rejecting lignin upon antisolvent addition with optimal conditions for AGB at 120 °C for 3 h [8, 30]. To provide lower cost biorefinery feedstock inputs, MSW have been used as a blending agent in different feedstocks (e.g., corn stover) using IL pretreatment with advantageous features such as year-round availability, reduce landfill disposal and meet biorefinery overall quality specifications [9]. Recently, different studies have been carried out to determine the impact and effectiveness on pretreatment technologies of mixed lignocellulosic biomass as the feedstock costs remain a large contributor to biofuel production costs including that each material responds differently to a specific process (e.g., component removal, sugar yield) [29, 35, 36].

The process flowsheet of the IL-water pretreatment systems is shown in Fig. 2. Figure 3 presents the compositional analysis of untreated and all 14 IL-water pretreatment system using AGB, MSW, and AGB/MSW (1:1) blend where three major plant cell wall components (glucan, xylan, and lignin) were monitored. For the untreated AGB, a 31.3% glucan, 15.4% xylan, and 21.6% lignin compositional profile measured is comparable to other agave bagasses from the Tequilana species, but relatively lower in glucan content and higher in lignin compared to other reported agave compositions which had glucan and lignin values above 40% and under 20%, respectively [37, 38]. This difference can potentially be attributed to process conditions during tequila production and/or environmental conditions of the biomass source, extraction, and post-harvest procedures. Compositional profile of untreated MSW was 54.7% glucan, 12.9% xylan, and 12.5% lignin, similar to that reported by Sun et al. [9] and similar to the individual composition from two constituents of MSW (newspaper and office paper) described by Foyle et al. [39]. As expected, intermediate values were obtained for the AGB/MSW (1:1) blend with 43.9% glucan, 14.1% xylan, and 16.7% lignin.

In order to measure the response of each component from the aqueous IL systems, 100% concentration of [C2C1Im][OAc], [C4C1Im][OAc], and water was included in the experimental design as systems A, F, and N, respectively.

Compositional profiles for pretreated samples (Fig. 3) indicate that almost all systems studied achieve a higher glucan content increase (2–24%) with the exception of system N (100% water) where negative values for MSW and AGB/MSW (1:1) blend were obtained. Using system J with ~40% water obtained a ~24% glucan increase with AGB that was higher than the one obtained with system A (18%) when compared to the untreated sample.

A~9% glucan increase using MSW was achieved obtained in three systems (I, J, and M) and was comparable to the trends obtained by Sun et al. [9] that reports an increment of 6% of glucan when compared to the untreated biomass. Finally, the AGB/MSW (1:1) blend increased the glucan content by 15 and ~10% with system L and I, respectively. In terms of xylan content, the pretreated AGB showed a similar trend as in previous reports, increasing its loading from 1 to 18%. As opposite as in MSW, where the general trend shows a xylan reduction up to 9% in the IL-treated samples while the AGB/MSW (1:1) blend presents mix results.

One of the most important features of IL pretreatment is the high levels of delignification that can be achieved. When compared to the untreated AGB, a significant reduction in lignin content was observed after pretreatment. Lignin content was decreased up to 26.9% with system J (~40% water) comparable to that using system A (100% [C2C1Im][OAc]) which was our base control. Nevertheless, with MSW slight increases were observed with the IL-treated samples and these differences may be attributed to the nature of the lignin in these two feedstocks. A recent study investigated the [C2C1Im][OAc] dissolution of a corn stover/MSW (1:1) blend at 140 °C from 1 to 3 h, and obtained lignin reduction of 46.2, 69.5, and −0.8% for the blend, corn stover, and MSW, respectively, where a negative number stands for a relative increase on lignin content [9].

Lignin removal from the AGB/MSW (1:1) blend was obtained with system A (15.1%) and system J (14.4%), and were not statistically different. This represents a cost savings since system J uses 40% less IL than system A which is neat IL. In this context, Fu and Mazza [40] presented delignification values of 3.6 and 5.6% with a mixture solution of 1:1 [C2C1Im][OAc]/water with neat [C2C1Im][OAc] using Triticale straw. Furthermore, Shi et al. [35] showed that a high sugar yield could be obtained using mixed lignocellulosic feedstocks in which IL pretreatment is capable of handling them with equal efficiency.

Sun et al. [9] attribute the difference on delignification to the nature of lignin in MSW, as this paper mix has already gone through a pulping process that removed most of the lignin although, lignin structure in the MSW is thus expected to be more recalcitrant compared to the intact lignin in AGB making it more difficult to be extracted.

Summarizing, in general terms, system A as expected from neat [C2C1Im][OAc] presented positive improvement in terms of lignin removal and glucan enrichment from the studied aqueous IL systems and biomass feedstocks while when only water was used (system N), the process temperature (120 °C) was not high enough to substantially modify the biomass cell wall. The intrinsic variation in the cell wall components from the studied materials made that the response on which IL-aqueous system reduce the biomass recalcitrance on higher or lesser magnitude as in the AGB.

ATR-FTIR analysis

Normalized FTIR spectra between 800 and 2000 cm−1 were used to characterize the chemical fingerprints of the feedstocks before and after IL pretreatment (see Additional file 1). For ATR-FTIR data, seven bands are used to monitor the chemical changes of lignin and carbohydrates, and two bands for changes in calcium oxalate intensity in AGB. As expected, the main antisymmetric carbonyl stretching band specific to the oxalate family occurs at 1618 cm−1 for calcium oxalate and the secondary carbonyl stretching band, the metal-carboxylate stretch, is located at 1317 cm−1. Those two bands are observed to decrease with IL pretreatment in all AGB samples, in agreements with a previous report [30]. Calcium oxalate is located in a large group in the AGB/MSW (1:1) blend but does not appear in MSW. Only AGB presents the 1745 cm−1 in a great the intensity and a reduction trend was found in all IL-treated samples. This band is associated with carbonyl C=O stretching, indicating cleavage of lignin and side chains increasing slightly only on system N (100% water). The mixture employed to represent MSW (glossy paper, non-glossy paper, non-glossy cardboard, and glossy cardboard) has an untreated spectrum similar to those obtained from newspaper and paper [41–43]. Typically, the bands at 1510 and 1605 cm−1 show the aromatic skeletal vibrations of lignin and are used to reflect the delignification that occurs during IL pretreatment when compared to the untreated spectrum. These bands are assigned for C=O stretching in conjugated p-substituted aryl ketones [44]. In AGB and in some samples of the AGB/MSW (1:1) blend, these bands (1510 and 1605 cm−1) are affected by the broad and intense calcium oxalates peaks, which does not occur with MSW. An increase is shown in the IL-treated samples of the band at 1375 cm−1 (C–H deformation in cellulose and hemicellulose).

Furthermore, a significant increase of band intensities is observed in all samples at 1056 cm−1 (C–O stretch in cellulose and hemicellulose), and the band intensity at 1235 cm−1 (C–O stretching in lignin and hemicellulose). In addition to that, the crystalline-to-amorphous cellulose ratio peaks of 1098 and 900 cm−1 decreased as a function of IL pretreatment temperature, indicating reduction of cellulose crystallinity in most of pretreated samples when compared to the untreated spectrum [6]. Finally, an increase in the band intensity at 900 cm−1 (antisymmetric out-of-plane ring stretch of amorphous cellulose) is observed in the spectra of IL-treated samples, which reflects the relative increase in cellulose content as a result of partial removal of both lignin and hemicellulose in the biomass AGB, MSW, and AGB/MSW (1:1) blend.

Comparison of the enzymatic saccharification of aqueous IL-treated biomass

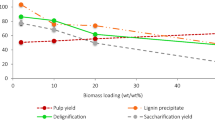

Figure 4 shows the 72 h glucan and xylan conversion of AGB, MSW, and AGB/MSW (1:1) blend. As expected from untreated samples, all three feedstocks showed values under 26 and 14% in terms of xylan conversion. On the other hand, system N (100% water) displayed sugar conversions similar to the untreated samples, as process temperature was not high enough to initiate autohydrolysis.

The AGB using system J had a (97.6%) glucan conversion similar to system A (94.7%) offering an advantage in terms of IL utilization where a relatively high water content (~40%) maintained a sugar conversion comparable to neat IL pretreatment (Fig. 4-IA), correlated with high delignification values. For IL pretreated MSW (Fig. 4-IIA), 96.7% of glucan conversion was obtained with system J, whereas conversion values above 90% were reached when neat systems were employed. When IL-water mixtures were used, System D (10.1% water) achieved a high glucan conversion (~93%), in contrast with system L (50% water) with an 83.1%. Agave bagasse and MSW obtained xylan conversion yields above 87 and 76% for system A and B, respectively (Fig. 4-IB, IIB).

Saccharification of AGB/MSW (1:1) blend showed a 72-h glucan conversion of 96.8% (system A), 94.1% (system D, ~10% water), and 83.0% (system J, ~40% water) (Fig. 4-IIIA). Hence, a high sugar conversion was obtained using the AGB/MSW (1:1) blend in an IL system with an equal efficiency as that obtained using neat [C2C1Im][OAc]. In terms of xylan conversion of the AGB/MSW (1:1) blend, 92.2% was obtained using system A, while IL-water systems were in the range of 65–78% (Fig. 4-IIIB). The improved saccharification for IL pretreated samples was due to the decrease biomass recalcitrance granted by weaken the van der Waals interaction between cell wall polymers and disrupt the covalent linkages between hemicellulose and lignin [36].

Table 1 shows a comparison with selected pretreatments that maximize enzymatic digestibility of AGB and MSW. Each pretreatment has it distinctive operation parameters and interaction with the lignocellulosic biomass where IL pretreatment outperformed other processes wits fast saccharification rates and high sugar yields where this difference could be attributed to an improved substrate availability.

Overall, all three biomass samples can be efficiently saccharified obtaining a high sugar conversion when compared to the untreated samples, and comparable sugar yields were observed for the IL mixtures relative to those obtained with neat ILs.

A few reports exist where IL-water systems have been used to investigate the dissolution of lignocellulosic biomass using imidazolium-based cation.

Fu and Mazza [40] study the [C2C1Im][OAc]-water pretreatment of triticale straw at 150 °C for 90 min, and achieved a sugar yield of 81 for 50% water and 67% for neat IL, which were lower than the glucan conversion efficiency of 98% for AGB (40% water) and 83% for MSW (50% water) switchgrass at 120 °C for 3 h in this study. Similarly, Brandt et al. [45] using aqueous solutions applied two ionic liquids (1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium methyl sulfate [C4C1Im][MeSO4] and 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate [C4C1Im][HSO4]) in Miscanthus pulp at 120 °C, and were able to achieve a glucan conversion of 85% and 92% using solutions containing 40% and 10% water content, respectively. Nonetheless, the [C4C1Im][MeSO4] pretreatment was carried out for 22 h, while [C4C1Im][HSO4] pretreatment lasted 13 h, higher processing times values than the 3 h in this study. Another paper reported 88% glucose yield from sugarcane bagasse using [C4C1Im][Cl] solution containing 20% water and 1.6% H2SO4 at 130 °C for 30 min [46]. In addition, Shi et al. [47] show that 50–80% [C2C1Im][OAc]-water mixtures at 160 °C in switchgrass can match the performance of neat [C2C1Im][OAc] in terms of glucose yield.

Finally, taking into consideration the decreased use of ILs when mixing with up to 40% water, this will impact process economics by reducing associated costs with recycling and handling (with a less viscous solution). This method is also very versatile when employing mixed biomass due to feedstock flexibility, where MSW can provide a lower cost and reduce the environmental impact on subsequent landfill disposal.

IL recycling

In order to obtain an affordable and scalable IL conversion technology, an efficient process for the recycle and reuse of the ILs is mandatory. In addition, dissolved lignin and/or xylan could be recovered; hence, an added value to the overall process can be attained. The effects of recycled ILs and their impact on biomass pretreatment have not been completely elucidated. By addition of an antisolvent (water), a major fraction of the cellulosic content of the biomass can be recovered from the IL solution forming a single phase. In this study, we used the recovered IL/water mixtures from system A and system B to perform 3 subsequent recycle steps by IL pretreating fresh untreated AGB (120 °C and 3 h), and conclude with a saccharification step (Fig. 5). The IL recycling was performed to test imidazolium-based ionic liquids using only AGB (as a more homogenous sample than MSW), to understand the feasibility of pretreatment and possible changes of its molecular structure. Approximately, 85–90% of IL was recovered on each recycle. Figure 6 presents the 1H-NMR and Additional file 2 shows the FTIR analysis of 3 series of recycled [C2C1Im][OAc] and [C4C1Im][OAc] in AGB. Based on both spectra, [C2C1Im][OAc] and [C4C1Im][OAc] appear to hold their structure as shown on their proton spectra and the distinctive FTIR bands (1175, 1378, and 1574 cm−1) from fresh ILs to the recycled ones. Recycled [C2C1Im][OAc] shows an extra peak at 3.6 ppm suggesting that recycled IL contained residual sugars; however, these sugars did not affect its recycle. This may be probably due to relatively severe recycle conditions employed (100 °C—12 h). Nonetheless, this did not have a significant effect on biomass crystallinity of AGB using fresh ILs or recycled ILs. In addition, we have observed methoxyl peak (~2.5 ppm) in the 1H NMR, suggesting that the change in color of IL is partly due to the presence of lignin.

The ratios of crystalline to amorphous cellulose and disordered components found in untreated, fresh ILs, and recycled IL were used to determine the crystallinity index (CrI), as cellulose crystallinity has shown to affect the enzymatic saccharification. Both AGB samples pretreated with fresh ILs present a transition from cellulose I polymorph to cellulose II polymorph as the (002) peak around 22.1° was shifted to a lower angle (20.6°) after IL pretreatment (see Additional file 3). The CrI of the pretreated samples decreased when compared to the untreated sample.

The CrI obtained from the samples generated by the 100% IL processes is higher than that of those obtained from the recycled samples, although this assessment could be affected by the interference of sharp crystalline peaks of calcium oxalate at 2θ = 15°, 24.5°, and 30.5° [30]. In terms of glucan conversion, [C2C1Im][OAc] was in the range of ~85 to ~95% in the recycled experiments, while [C4C1Im][OAc] from ~67 to ~71% (Fig. 7). Similarly, Shill et al. [27] show that a 90% glucan conversion was still maintained using up to 2 recycling steps of [C2C1Im][OAc] at 140 °C and 1 h using Miscanthus. Furthermore, xylan conversion was maintained in a 10% range for both ILs. A significant difference was obtained only on the 2nd recycle of [C2C1Im][OAc] which did not occur with [C4C1Im][OAc]. This may be solved with other recycling strategies such as the one recently applied by Sathitsuksanoh et al. [54] that used alcohols as alternative precipitating agents with IL pretreatment process.

Conclusions

Ternary IL-water systems for the pretreatment of mixed feedstock (such as AGB and MSW) enable delignification and sugar conversion at similar levels to 100% IL. Mixing ILs such as [C2C1Im][OAc] and [C4C1Im][OAc] results in an effective method to pretreat biomass with different price ranges while maintaining performance. In addition, effectiveness of [C2C1Im][OAc] and [C4C1Im][OAc] during biomass pretreatment remains intact with up to 40% water content. MSW presents relatively higher sugar yield than AGB, whereas the AGB/MSW (1:1) blend shows a glucan conversion of 94.1 and 83.0% using an IL system with ~10 and ~40% water content, respectively. Dissolution of biomass cellulose was also efficient using recycled ILs with only ~10% decrease in glucan, and xylan conversion yields were observed when a 2nd IL recycle was used in comparison with fresh IL. The same effect occurred with cellulose crystallinity of IL-treated biomass where comparable results were obtained when pure and recycle ILs were employed. The chemical structures of neat and recycled ILs demonstrate strong similarities in their behavior, as observed by FTIR and 1H-NMR spectroscopy. Altogether, this study highlights the potential of blending MSW as a potentially low-cost feedstock, as using IL-water systems with imidazolium-based ILs mixtures yield comparable biomass treatment results as with pure ILs. Finally, the promising IL recycling results indicate that this strategy can be used and further integrated with downstream saccharification and fermentation within a biorefinery scheme to reduce total operation costs.

Abbreviations

- [C2C1Im][OAc]:

-

1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate

- [C4C1Im][OAc]:

-

1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate

- AGB:

-

agave bagasse

- DI:

-

deionized

- FTIR:

-

Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy

- HPLC:

-

high-performance liquid chromatography

- IL:

-

ionic liquid

- MSW:

-

municipal solid waste

- NMR:

-

nuclear magnetic resonance

References

Wu H, Mora-Pale M, Miao J, Doherty TV, Linhardt RJ, Dordick JS. Facile pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass at high loadings in room temperature ionic liquids. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2011;108:2865–75.

Jørgensen H, Kristensen JB, Felby C. Enzymatic conversion of lignocellulose into fermentable sugars: challenges and opportunities. Biofuels Bioprod Bioref. 2007;1:119–34.

Kumar P, Barrett DM, Delwiche MJ, Stroeve P. Methods for pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for efficient hydrolysis and biofuel production. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2009;48:3713–29.

Trinh LTP, Lee YJ, Lee J-W, Lee H-J. Characterization of ionic liquid pretreatment and the bioconversion of pretreated mixed softwood biomass. Biomass Bioenerg. 2015;81:1–8.

Singh S, Simmons BA, Vogel KP. Visualization of biomass solubilization and cellulose regeneration during ionic liquid pretreatment of switchgrass. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;104:68–75.

Li C, Knierim B, Manisseri C, Arora R, Scheller HV, Auer M, Vogel KP, Simmons BA, Singh S. Comparison of dilute acid and ionic liquid pretreatment of switchgrass: biomass recalcitrance, delignification and enzymatic saccharification. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:4900–6.

Li C, Cheng G, Balan V, Kent MS, Ong M, Chundawat SPS, daCosta SL, Melnichenko YB, Dale BE, Simmons BA, Singh S. Influence of physico-chemical changes on enzymatic digestibility of ionic liquid and AFEX pretreated corn stover. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102:6928–36.

Perez-Pimienta JA, Lopez-Ortega MG, Varanasi P, Stavila V, Cheng G, Singh S, Simmons BA. Comparison of the impact of ionic liquid pretreatment on recalcitrance of agave bagasse and switchgrass. Bioresour Technol. 2013;127:18–24.

Sun N, Xu F, Sathitsuksanoh N, Thompson VS, Cafferty K, Li C, Tanjore D, Narani A, Pray TR, Simmons BA, Singh S. Blending municipal solid waste with corn stover for sugar production using ionic liquid process. Bioresour Technol. 2015;186:200–6.

Sun N, Rahman M, Qin Y, Maxim ML, Rodriguez H, Rogers RD. Complete dissolution and partial delignification of wood in the ionic liquid 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate. Green Chem. 2009;11:646–55.

Brandt A, Grasvik J, Hallett JP, Welton T. Deconstruction of lignocellulosic biomass with ionic liquids. Green Chem. 2013;15:550–83.

Konda NM, Shi J, Singh S, Blanch HW, Simmons BA, Klein-Marcuschamer D. Understanding cost drivers and economic potential of two variants of ionic liquid pretreatment for cellulosic biofuel production. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2014;7:86.

Juneja A, Kumar D, Murthy GS. Economic feasibility and environmental life cycle assessment of ethanol production from lignocellulosic feedstock in Pacific Northwest U.S. J Renew Sustain Energ. 2013;5:023142.

Li C, Tanjore D, He W, Wong J, Gardner JL, Thompson VS, Yancey NA, Sale KL, Simmons BA, Singh S. Scale-up of ionic liquid-based fractionation of single and mixed feedstocks. Bioenergy Res. 2015;8(3):982–91.

Shi J, Thompson V, Yancey N. Impact of mixed feedstocks and feedstock densification on ionic liquid pretreatment efficiency. Biofuels. 2013;4:63–72.

Hou XD, Li N, Zong MH. Facile and simple pretreatment of sugar cane bagasse without size reduction using renewable ionic liquidswater mixtures. ACS Sustaine Chem Eng. 2013;1:519–26.

Xia S, Baker GA, Li H, Ravula S, Zhao H. Aqueous ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents for cellulosic biomass pretreatment and saccharification. RSC Adv. 2014;4:10586–96.

Swatloski Richard P, Spear Scott K, Holbrey John D, Rogers Robin D. Dissolution of cellulose with ionic liquids. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:4974–5.

Kohno Y, Ohno H. Ionic liquid/water mixtures: from hostility to conciliation. Chem Comm. 2012;48:7119.

Wang Q, Chen Q, Mitsumura N, Animesh S. Behavior of cellulose liquefaction after pretreatment using ionic liquids with water mixtures. J Appl Polym Sci. 2014;131:1–8.

Brandt A, Hallett JP, Leak DJ, Murphy RJ, Welton T. The effect of the ionic liquid anion in the pretreatment of pine wood chips. Green Chem. 2010;12:672–9.

Parthasarathi R, Balamurugan K, Shi J, Subramanian V, Simmons BA, Singh S. Theoretical insights into the role of water in the dissolution of cellulose using IL/water mixed solvent systems. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119:acs.jpcb.5b02680.

George A, Brandt A, Tran K, Zahari SMSNS, Klein-Marcuschamer D, Sun N, Sathitsuksanoh N, Shi J, Stavila V, Parthasarathi R, Singh S, Holmes BM, Welton T, Simmons BA, Hallett JP. Design of low-cost ionic liquids for lignocellulosic biomass pretreatment. Green Chem. 2015;17:1728–34.

Qiu Z, Aita GM. Pretreatment of energy cane bagasse with recycled ionic liquid for enzymatic hydrolysis. Bioresour Technol. 2013;129:532–7.

Zhang Z, O’Hara IM, Doherty WOS. Pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse by acid-catalysed process in aqueous ionic liquid solutions. Bioresour Technoly. 2012;120:149–56.

An Y-X, Zong M-H, Wu H, Li N. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass with renewable cholinium ionic liquids: biomass fractionation, enzymatic digestion and ionic liquid reuse. Bioresour Technol. 2015;192:165–71.

Shill K, Padmanabhan S, Xin Q, Prausnitz JM, Clark DS, Blanch HW. Ionic liquid pretreatment of cellulosic biomass: enzymatic hydrolysis and ionic liquid recycle. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2011;108:511–20.

Gao J, Chen L, Yuan K, Huang H, Yan Z. Ionic liquid pretreatment to enhance the anaerobic digestion of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour Technol. 2013;150:352–8.

Klein-Marcuschamer D, Simmons BA, Blanch HW. Techno-economic analysis of a lignocellulosic ethanol biorefinery with ionic liquid pre-treatment. Biofuel Bioprod Bioref. 2011;5:562–9.

Perez-Pimienta JA, Lopez-Ortega MG, Chavez-Carvayar JA, Varanasi P, Stavila V, Cheng G, Singh S, Simmons BA. Characterization of agave bagasse as a function of ionic liquid pretreatment. Biomass Bioenerg. 2015;75:180–8.

Sluiter A, Hames B, Ruiz RO, Scarlata C, Sluiter J, Templeton D, Energy D of. Determination of structural carbohydrates and lignin in biomass. Biomass Anal Technol Team Lab Anal Proced. 2004;2011(July):1–14.

Shill K, Miller K, Clark DS, Blanch HW. A model for optimizing the enzymatic hydrolysis of ionic liquid-pretreated lignocellulose. Bioresour Technol. 2012;126:290–7.

Segal L, Creely JJ, Martin AE, Conrad CM. An empirical method for estimating the degree of crystallinity of native cellulose using the X-ray diffractometer. Text Res J. 1959;29:786–94.

Duncan DB. Multiple range and multiple F tests. Biometrics. 1955;11:1–42.

Shi J, George KW, Sun N, He W, Li C, Stavila V, Keasling JD, Simmons BA, Lee TS, Singh S. Impact of pretreatment technologies on saccharification and isopentenol fermentation of mixed lignocellulosic feedstocks. Bioenergy Res. 2015;8:1004–13.

Li C, Sun L, Simmons BA, Singh S. Comparing the recalcitrance of eucalyptus, pine, and switchgrass using ionic liquid and dilute acid pretreatments. Bioenergy Res. 2013;6:14–23.

Ávila-Lara AI, Camberos-Flores JN, Mendoza-Pérez JA, Messina-Fernández SR, Saldaña-Duran CE, Jimenez-Ruiz EI, Sánchez-Herrera, Leticia M, Pérez-Pimienta JA. Optimization of alkaline and dilute acid pretreatment of agave bagasse by response surface methodology. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2015;3:146.

Davis SC, Dohleman FG, Long SP. The global potential for Agave as a biofuel feedstock. GCB Bioenergy. 2011;3:68–78.

Foyle T, Jennings L, Mulcahy P. Compositional analysis of lignocellulosic materials: evaluation of methods used for sugar analysis of waste paper and straw. Bioresour Technol. 2007;98:3026–36.

Fu D, Mazza G. Aqueous ionic liquid pretreatment of straw. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102:7008–11.

Subhedar PB, Gogate PR. Alkaline and ultrasound assisted alkaline pretreatment for intensification of delignification process from sustainable raw-material. Ultrason Sonochem. 2014;21:216–25.

Polovka M, Polovková J, Vizárová K, Kirschnerová S, Bieliková L, Vrška M. The application of FTIR spectroscopy on characterization of paper samples, modified by Bookkeeper process. Vib Spectrosc. 2006;41:112–7.

Smidt E, Böhm K, Schwanninger M. The application of FT-IR spectroscopy in waste management. In: Nikolic GH, editor. Fourier transforms - new analytical approaches and FTIR strategies. Rijeka: InTech; 2011. p. 251–306.

Zhao X-B, Wang L, Liu D-H. Peracetic acid pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse for enzymatic hydrolysis: a continued work. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2008;83:950–6.

Brandt A, Ray MJ, To TQ, Leak DJ, Murphy RJ, Welton T. Ionic liquid pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass with ionic liquid-water mixtures. Green Chem. 2011;13:2489–99.

Zhang Z, O’Hara I, Doherty W. Effects of pH on pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse using aqueous imidazolium ionic liquids. Green Chem. 2013;15:431–8.

Shi J, Balamurugan K, Parthasarathi R, Sathitsuksanoh N, Zhang S, Stavila V, Subramanian V, Simmons B, Singh S. Understanding the role of water during ionic liquid pretreatment of lignocellulose: co-solvent or anti-solvent? Green Chem. 2014;16:3830–40.

Perez-Pimienta JA, Flores-Gómez CA, Ruiz HA, Sathitsuksanoh N, Balan V, da Costa Sousa L, Dale BE, Singh S, Simmons BA. Evaluation of agave bagasse recalcitrance using AFEX™, autohydrolysis, and ionic liquid pretreatments. Bioresour Technol. 2016;211:216–23.

Montella S, Balan V, Sousa C, Gunawan C, Giacobbe S, Pepe O, Faraco V. Saccharification of newspaper waste after ammonia fiber expansion or extractive ammonia. AMB Express. 2016;6:18.

Velázquez-Valadez U, Farías-Sánchez JC, Vargas-Santillán A, Castro-Montoya AJ. Tequilana weber agave bagasse enzymatic hydrolysis for the production of fermentable sugars: oxidative-alkaline pretreatment and kinetic modeling. Bioenergy Res. 2016;9:998–1004.

Saucedo-Luna J, Castro-Montoya AJ, Martinez-Pacheco MM, Sosa-Aguirre CR, Campos-Garcia J. Efficient chemical and enzymatic saccharification of the lignocellulosic residue from Agave tequilana bagasse to produce ethanol by Pichia caribbica. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;38:725–32.

Shi J, Mirvat E, Yang B, Wyman CE. The potential of cellulosic ethanol production from municipal solid waste: a technical and economic evaluation. Berkeley: University of California Energy Institute; 2009.

Perez-Pimienta JA, Poggi-Varaldo HM, Ponce-Noyola T, Ramos-Valdivia AC, Chavez-Carvayar JA, Stavila V, Simmons BA. Fractional pretreatment of raw and calcium oxalate-extracted agave bagasse using ionic liquid and alkaline hydrogen peroxide. Biomass Bioenerg. 2016;91:48–55.

Sathitsuksanoh N, Sawant M, Truong Q, Tan J, Canlas CG, Sun N, Zhang W, Renneckar S, Prasomsri T, Shi J, Çetinkol Ö, Singh S, Simmons BA, George A. How alkyl chain length of alcohols affects lignin fractionation and ionic liquid recycle during lignocellulose pretreatment. Bioenergy Res. 2015;8:973–81.

Authors’ contributions

JAP carried out the biomass pretreatment, compositional analysis, ionic liquid recycle, saccharification work, and drafted the manuscript. NS performed the NMR analysis and drafted the NMR-related parts of the manuscript. KT contributed to compositional analysis and sugar analysis work. VT produced the MSW blends. VS performed the XRD analysis, calculated the crystallinity index of the samples, and drafted XRD-related parts of the manuscript. SS and BAS contributed to the original experimental design. TP, SS, and BAS conceived the study, participated in its design, coordination, and drafted the manuscript. All authors suggested modifications to the draft and approved the final manuscript. We have read Biotechnology for Biofuels policy on data and material release, and the data within this manuscript meet those requirements. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Novozymes for the gift of the Cellic® CTec2 and HTec2 enzyme cocktails.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of supporting data

The data supporting our findings can be found in this manuscript and in the additional files provided.

Consent for publication

The authors agree to publish in the journal.

Funding

This work was part of the DOE Joint BioEnergy Institute (http://www.jbei.org) supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, through Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231 between Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the US Department of Energy. NS was partially supported by the National Science Foundation under Cooperative Agreement No. 1355438.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

13068_2017_758_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1. FTIR spectra of untreated and pretreated biomass under different ionic liquid–water systems. Unt: untreated, AGB: agave bagasse, MSW: municipal solid waste, Blend: agave bagasse/municipal solid waste (1:1) blend. FTIR spectra of all untreated and pretreated samples from agave bagasse, municipal solid waste and the agave bagasse/municipal solid waste (1:1) blend between 800 and 2000 cm−1 with a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1.

13068_2017_758_MOESM2_ESM.docx

Additional file 2. Chemical changes tracked of fresh and recycled [C2C1Im][OAc] (up) and [C4C1Im][OAc] (down). FTIR spectra of recycled ionic liquids [C2C1Im][OAc] and [C4C1Im][OAc] from three different cycles.

13068_2017_758_MOESM3_ESM.docx

Additional file 3. XRD spectrum and crystallinity index (CrI) of agave bagasse under different conditions (untreated, Fresh IL pretreated and IL-recycled). XRD diffractograms of untreated and pretreated agave bagasse under different process conditions.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Perez-Pimienta, J.A., Sathitsuksanoh, N., Thompson, V.S. et al. Ternary ionic liquid–water pretreatment systems of an agave bagasse and municipal solid waste blend. Biotechnol Biofuels 10, 72 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-017-0758-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-017-0758-4