Abstract

Introduction

This study aimed at evaluating the overall survival (OS) gain associated with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-directed therapies in patients with metastatic breast cancer (mBC).

Methods

A bibliographic search was conducted in PubMed and Cochrane databases. Only phase III randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including HER2-positive (HER2+) mBC patients were included in this review. OS was defined as time from randomization until the occurrence of death from any cause. Studies have been grouped according to the line of treatment, i.e., first-line or second-line or beyond.

Results

Nineteen RCTs were eligible for inclusion, of which 12 assessed therapies targeting HER2+ mBC in the first-line setting. OS improved from 20.3 months in the first RCT (standard chemotherapy; Slamon et al. (N Engl J Med 344:783–92, 2001)) evaluating HER2-targeting therapies to 48 months in the study of Swain et al. (Lancet Oncol 14:461–71, 2013), with triple combination of pertuzumab, trastuzumab and docetaxel. Seven RCTs evaluated the OS of HER2-targeting therapies in the second-line setting and beyond. The OS in second-line setting improved from 15.3 months (capecitabine; Cameron et al. (Breast Cancer Res Treat 112:533–43, 2008)) to 30.7 months (trastuzumab emtansine; Verma et al. (N Engl J Med 367:1783–91, 2012)). In the third-line setting, the association of lapatinib and trastuzumab has demonstrated to improve OS to 4.5 months compared with lapatinib alone (14 months vs. 9.5 months; Blackwell et al. (J Clin Oncol 30:2585–92, 2012)).

Conclusions

HER2-directed therapies had an undeniable beneficial impact on the OS of patients with HER2+ mBC. The triple combination of docetaxel, pertuzumab and trastuzumab is associated with a survival extent of more than 4.5 years, compared with a life expectancy of 1.5 years achieved 14 years ago.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the second most common cancer worldwide and, by far, the most frequent among women with an estimated 1.67 million new cases diagnosed in 2012 (25 % of all cancers) (Ferlay et al. [6]). BC is the fifth cause of death from cancer overall (522,000 deaths) and it is the most frequent cause of cancer death in women in less developed regions (324,000 deaths, 14.3 % of the total) (Ferlay et al. [6]). In the developed countries, it is the second cause of cancer death (198,000 deaths, 15.4 %), after lung cancer (Ferlay et al. [6]).

In developed countries between 6 and 10 % of women will have metastatic disease when diagnosed with BC (Dawood et al. [7]); in developing countries this percentage can reach 60 %. Depending on initial stage, tumor biology, and type of treatment scheme received, between 30 and 50 % of women with early BC will relapse (Cardoso et al. [8]).

The amplification of the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) is observed in 25 to 30 % of all BCs (Slamon et al. [1]). Patients with BC with overexpression of HER2 have, originally, a poorer prognosis and shorter overall survival (OS) (Tandon et al. [9]; Slamon et al. [10]).

The development of effective HER2-targeted drugs is considered a major breakthrough in BC therapy. Trastuzumab was the first anti-HER2 drug approved for treatment of HER2-positive (HER2+) metastatic BC, either alone or in combination with chemotherapy (Slamon et al. [1]). This anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody was associated with a significantly longer time to disease progression, higher response rate, longer response duration, and improved overall survival (Slamon et al. [1]). During the last decade, HER2-targeted therapeutic approaches continued to evolve with a positive impact on the survival of the women with HER2+ metastatic BC (Dawood et al. [7]).

This study aimed at evaluating the survival gains associated with HER2-targeted therapies in patients with HER2+ metastatic BC.

Methods

Data sources and searches

A bibliographic search was conducted in the PubMed and in Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases (updated October 2015). The search equation comprised terms referring to HER2+ metastatic BC (Additional file 1). No language restrictions were applied. The references lists of systematic reviews were revised in order to identify further studies.

Two reviewers (DM and CA) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of retrieved articles to determine trial inclusion. In case of disagreement, the opinion of a third investigator was sought (BM).

Study selection

Only phase III randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including patients with HER2+ metastatic BC have been analyzed, irrespective of the treatment administered (i.e., chemotherapy and/or hormone therapy, chemotherapy and/or hormone therapy plus HER2-targeted therapy).

Data extraction

Data were abstracted in a standardized format by two independent reviewers (DM and CA). The data retrieved from each publication included study name, bibliographic reference, publication year, total number of patients allocated to each treatment arm on the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, characterization of the target population, and efficacy outcomes. The primary efficacy outcome was OS (defined as the time from random assignment until death from any cause), while the secondary outcome was progression-free survival (PFS, defined as the time from randomization until objective tumor progression or death) (FDA [11]). We extracted the median duration (in months) for the outcomes OS and PFS, based on the ITT analysis. Where outcome measures were not reported, we contacted the investigators to provide the data.

Studies were divided according to the line of treatment, i.e., first-line or second-line and beyond.

Data analyses

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Results

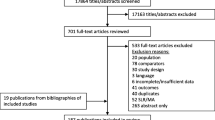

Figure 1 shows the flow of the search strategy criteria. The electronic databases searches returned 634 potentially relevant articles; 168 references were duplicates. After review of the titles and abstracts, 366 references were refuted and 100 were selected for further evaluation. After the application of the inclusion criteria, 19 RCTs reported in 26 publications were included (Andersson et al. [12]; Baselga et al. [13]; Baselga et al. [14]; Guan et al. [15]; Inoue et al. [16]; Johnston et al. [17]; Kaufman et al. [18]; Robert et al. [19]; Schwartzberg et al. [20]; Slamon et al. [1]; Swain et al. [2]; Swain et al. [21]; Valero et al. [22]; André et al. [23]; Blackwell et al. [24]; Blackwell et al. [5]; Cameron et al. [3]; Cameron et al. [25]; Geyer et al. [26]; Krop et al. [27]; Pivot et al. [28]; Verma et al. [4]; von Minckwitz et al. [29]; von Minckwitz et al. [30]; Gelmon et al. [31]; Hurwitz et al. [32]). Review of published manuscripts’ references did not find any other eligible studies.

First-line metastatic BC

Twelve phase III RCTs assessed therapies targeting HER2+ metastatic BC in the first-line setting (Slamon et al. [1]; Swain et al. [2]; Andersson et al. [12]; Baselga et al. [13]; Baselga et al. [14]; Guan et al. [15]; Inoue et al. [16]; Johnston et al. [17]; Kaufman et al. [18]; Robert et al. [19]; Schwartzberg et al. [20]; Swain et al. [21]; Valero et al. [22]; Gelmon et al. [31]; Hurwitz et al. [32]). The main results of each RCT are shown in Table 1. Figure 2 presents the OS (blue) and PFS (red) results for patients diagnosed with HER2+ metastatic BC receiving first-line treatment, according to the most effective treatment in each study.

Overall survival (blue) and progression-free survival (red) of patients diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer receiving first-line treatment, according to the most effective treatment in each study. Results are displayed from the study with lower OS to the study with higher OS. Results from the study by Inoue et al. [16], Gelmon et al. [31], and Hurwitz et al. [32] are not displayed because OS results were not provided. OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival

Chemotherapy ± trastuzumab or lapatinib

The first RCT assessing a therapy against HER2 for metastatic BC that overexpresses HER2 evaluated the efficacy and safety of standard chemotherapy plus trastuzumab versus standard chemotherapy alone (Slamon et al. [1]). In this study, the addition of trastuzumab to chemotherapy was associated with longer OS (25.1 vs. 20.3 months, p = 0.046) and longer PFS (6.9 vs. 4.5 months, p < 0.001) (Slamon et al. [1]). Inoue and colleagues evaluated the efficacy of sequential therapy with trastuzumab monotherapy followed by trastuzumab plus docetaxel after disease progression versus upfront combination therapy with trastuzumab and docetaxel as first-line therapy in patients with HER2+ metastatic BC. OS and PFS were significantly longer in the upfront trastuzumab and docetaxel group (median values not reported for OS, p = 0.04; median PFS of 14.6 vs. 3.7 months, p < 0.01) (Inoue et al. [16]). A trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of lapatinib plus paclitaxel compared to placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with newly diagnosed HER2+ metastatic BC showed that the addition of lapatinib to paclitaxel significantly improved OS and PFS versus paclitaxel (27.8 vs. 20.5 months, p = 0.0124; 9.7 vs. 6.5 months, p <0.001; respectively) (Guan et al. [15]).

Chemotherapy + lapatinib versus chemotherapy + trastuzumab

The MA.31 trial assessed the efficacy of lapatinib versus trastuzumab combined with taxanes as first-line treatments for HER2+ metastatic BC over 24 weeks, followed by the same anti-HER2 monotherapy until progression (Gelmon et al. [31]). Median OS was not observed. Median PFS was 9.0 months with lapatinib and 11.3 months with trastuzumab (p = 0.001) (Gelmon et al. [31]).

Hormone therapy ± trastuzumab or lapatinib

The TAnDEM study was the first phase III RCT combining a hormonal agent and trastuzumab without chemotherapy as treatment for HER2/hormone receptor–copositive metastatic BC (Kaufman et al. [18]). Postmenopausal women were randomly assigned to anastrozole with or without trastuzumab until progression; those receiving the monoclonal antibody in addition to anastrozole experienced a non-statistically significant improvement in OS (28.5 vs. 23.9 months, p = 0.325), but a statistically significant longer PFS (4.8 vs. 2.4 months, p = 0.0016) (Kaufman et al. [18]). A further study evaluated the effect of adding lapatinib, a dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor blocking both the epidermal growth factor receptor and the HER2 receptor, to the aromatase inhibitor letrozole in women with hormone receptor-positive metastatic BC (Johnston et al. [17]). The OS and the PFS in the HER2+ population were of 33.3 months and 8.2 months, respectively, in patients receiving lapatinib plus letrozole and 32.3 months and 3.0 months, respectively, in patients receiving letrozole (p = 0.113 and p = 0.019, respectively) (Johnston et al. [17]).

Chemotherapy A + trastuzumab versus chemotherapy B + trastuzumab

In 2006, the result of a trial evaluating the clinical benefit and safety of the addition of carboplatin to trastuzumab and paclitaxel versus trastuzumab and paclitaxel alone, reported no difference in OS (35.7 vs. 32.2 months, p = 0.76), but a significant improvement in PFS (10.7 vs. 7.1 months, p = 0.03) with the inclusion of carboplatin (Robert et al. [19]). The HERNATA study was designed to compare docetaxel with vinorelbine, both associated with trastuzumab, as first-line therapy of HER2+ locally advanced or metastatic BC (Andersson et al. [12]). In that trial, the OS and the PFS were of 38.8 months and 15.3 months, respectively, in the vinorelbine plus trastuzumab group and 35.7 months and 12.4 months, respectively, in the docetaxel plus trastuzumab group (p = 0.98 and p = 0.67) (Andersson et al. [12]). In the BCIRG 007 study, patients were randomly assigned to trastuzumab plus docetaxel or trastuzumab plus carboplatin and docetaxel, but no statistically significant differences were found between groups in OS (37.1 and 37.4 months, respectively; p = 0.99) and PFS (10.4 vs. 11.1 months, p = 0.57) (Valero et al. [22]).

Since the addition of trastuzumab to anthracyclines resulted in high incidence of cardiac toxicity in the pivotal trial conducted by Slamon and colleagues, Baselga and colleagues conducted a trial of first-line nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin plus trastuzumab and paclitaxel versus trastuzumab and paclitaxel alone in patients with HER2+ metastatic BC (Slamon et al. [1]; Baselga et al. [14]). The OS was 33.6 and 28.9 months, respectively (p = 0.083), and the median PFS was 16.1 and 14.5 months, respectively (p = 0.174) (Baselga et al. [14]). Thus, this trial failed to demonstrate a significant clinical improvement with the addition of nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin to the trastuzumab and paclitaxel regimen (Baselga et al. [14]).

Chemotherapy + trastuzumab and pertuzumab

In the CLEOPATRA study, patients with HER2+ metastatic BC who had not received previous chemotherapy or biological treatment for their metastatic disease were assigned to receive pertuzumab plus trastuzumab and docetaxel or placebo plus trastuzumab and docetaxel (Swain et al. [21]). Median OS in the pertuzumab group was estimated to be 56.5 months, compared to 37.6 months in the placebo (p < 0.001); the PFS was 18.7 in the pertuzumab group versus 12.4 months in the placebo group (p < 0.001) (Swain et al. [2]; Swain et al. [21]).

Everolimus in trastuzumab-resistant patients

The BOLERO-1 trial included women with HER2+, trastuzumab-resistant, locally recurrent invasive BC unamenable to resection with curative intent or metastatic BC who had not received previous trastuzumab or chemotherapy for the advanced stage of the disease (Hurvitz et al. [32]). Patients were randomly assigned to daily everolimus or placebo plus weekly trastuzumab and paclitaxel. OS analyses are still in progress. The median PFS was 14.95 months with everolimus and 14.49 months with placebo (p = 0.1166) in the full population; 20.27 months with everolimus and 13.08 with placebo in the hormone receptor-negative population (p = 0.0049; did not cross the protocol-specified threshold of p = 0.0044) (Hurvitz et al. [32]).

Second-line metastatic BC and beyond

Seven phase III RCTs (11 publications) evaluated therapies in the second-line setting or beyond (Table 2) (André et al. [23]; Blackwell et al. [24]; Blackwell et al. [5]; Cameron et al. [3]; Cameron et al. [25]; Geyer et al. [26]; Krop et al. [27]; Pivot et al. [28]; Verma et al. [4]; von Minckwitz et al. [29]; von Minckwitz et al. [30]). Figure 3 presents the OS (blue) and PFS (red) results for patients diagnosed with metastatic BC receiving second-line or beyond treatment, according to the most effective treatment in each study.

Overall survival (blue) and progression-free survival (red) of patients diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer receiving second-line treatment, according to the most effective treatment in each study. Results are displayed from the study with lower OS to the study with higher OS. Results from TH3RESA and BOLERO-3 are not displayed because OS results were not provided. GBG 26/BIG 03–05, German Breast Group 26/Breast International Group 03–05 study. OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival

Chemotherapy ± trastuzumab or lapatinib

The study by Geyer et al. [26], which included women with HER2+, locally advanced or metastatic BC that had progressed after trastuzumab-based therapy, who were randomly assigned to receive lapatinib plus capecitabine or capecitabine alone, did not report results on OS (Geyer et al. [26]), but an updated efficacy analysis showed that the OS was 15.6 months in patients receiving lapatinib plus capecitabine and 15.3 months in the capecitabine alone group (p = 0.177) (Cameron et al. [3]); while time to progression was of 8.4 months and 4.1 months, respectively (p < 0.001).

The GBG 26/BIG 3–05 phase III study, which included patients with HER2+ locally advanced or metastatic BC who had progressed during treatment with trastuzumab, reported no improvement in OS, but a statistically significant improvement of PFS in patients that received capecitabine with continuation of trastuzumab compared with those that received capecitabine alone (24.9 vs. 20.6 months, p = 0.73; 8.2 vs. 5.6 months, p = 0.0338, respectively) (von Minckwitz et al. [29], von Minckwitz et al. [30]). This trial changed an oncology paradigm since it showed that continuing trastuzumab beyond progression (associated with a different anticancer agent) was beneficial (von Minckwitz et al. [29], von Minckwitz et al. [30]).

Chemotherapy + trastuzumab or chemotherapy + lapatinib

Female patients with HER2+ metastatic BC and without central nervous system metastases were randomly assigned to receive lapatinib plus capecitabine or trastuzumab plus capecitabine in the CEREBEL trial (Pivot et al. [28]). Patients were required to have received prior chemotherapy for (neo)adjuvant or metastatic disease. Nevertheless, approximately 43 % of patients in the lapatinib plus capecitabine arm and 45 % of patients in the trastuzumab plus capecitabine arm had not received prior treatment for the metastatic disease (Pivot et al. [28]). PFS was longer with trastuzumab plus capecitabine (8.1 vs. 6.6 months, p = 0.021), with no differences in OS (27.3 vs. 22.7 months, p = 0.095) (Pivot et al. [28]).

Lapatinib + trastuzumab or lapatinib monotherapy

In the EGF104900 study, patients with heavily pretreated HER2+ metastatic BC were randomly assigned to receive lapatinib plus trastuzumab or lapatinib monotherapy as a third-line anti-HER treatment (Blackwell et al. [5]). Combination lapatinib plus trastuzumab significantly improved OS and PFS (14 vs. 9.5 months, p = 0.026; and 2.6 vs. 1.9 months, p = 0.010; respectively) (Blackwell et al. [5]).

Trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1)

Lapatanib plus capecitabine were further compared with trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) in the EMILIA trial that showed a statistically significant improvement of OS and PFS in patients treated with the latter regimen (25.1 vs. 30.9 months and 9.6 vs. 6.4 months, respectively, with p < 0.001 for both end points) (Verma et al. [4]).

In the TH3RESA trial patients with HER2+ unresectable locally advanced or recurrent BC or metastatic BC who had been treated with two or more HER2-directed regimens, including trastuzumab and lapatinib, were randomized to receive T-DM1 or treatment of physician’s choice (Krop et al. [27]). A trend favoring T-DM1 was observed on OS (p = 0.0034), but the stopping boundary was not crossed. PFS was significantly improved with T-DM1 (median 6.2 months vs. 3.3 months; p < 0.001) (Krop et al. [27]).

Everolimus in trastuzumab-resistant patients

The BOLERO-3 trial included women with HER2+, trastuzumab-resistant, advanced BC who had previously received taxane therapy (André et al. [23]). Patients were randomly assigned to daily everolimus plus weekly trastuzumab and vinorelbine or to placebo plus trastuzumab and vinorelbine. OS was not mature and median PFS was 7 months with everolimus and 5.8 months with placebo (p = 0.0067) (André et al. [23]).

Discussion and conclusions

The advances in early diagnosis and adjuvant pharmacological therapy have led to a decrease in mortality rates from BC in developed countries (Cardoso et al. [8]). Nonetheless, the prevalence of metastatic BC is still high. Many women live with the disease for several years, but there is, however, a lack of accurate data for this condition since most cancer registries do not capture relapses (Cardoso et al. [8]). Metastatic BC is not considered curable and the treatment goal includes improving patients’ quality of life and prolonging survival as much as possible (Cardoso et al. [8]).

In the early 1990s the median OS of patients diagnosed with metastatic BC was only 14 months (Chia et al. [33]). The introduction of more efficacious therapies has substantially improved the prognosis of these patients. The addition of HER2-targeted therapies to standard treatments is associated with marked improvement of OS in patients with metastatic BC. The first approved HER2-directed inhibitor, trastuzumab, led to an OS prolongation of 5 months when added to chemotherapy (Slamon et al. [1]), and became the standard of care in first-line treatment (Cardoso et al. [8]). The addition of lapatinib to paclitaxel also results in a prolongation of 7 months of OS compared with paclitaxel alone, as well as the prolongation of PFS (Guan et al. [15]). More recently, the MA.31 trial provided an answer to a relevant clinical question through a head-to-head comparison between trastuzumab and lapatinib (both combined with taxanes) as first-line treatments for HER2+ metastatic breast cancer (Gelmon et al. [31]). Compared to trastuzumab, lapatinib was associated with a shorter PFS and a worse safety profile, with increased diarrhea, appetite loss, social functioning, and skin rash (Gelmon et al. [31]). These results support the use of trastuzumab over lapatinib in patients with treatment-naïve HER2+ metastatic breast cancer, and have implications for clinical practice (Gelmon et al. [31]).

Other therapeutic combinations were evaluated in clinical trials, but not all led to the prolongation of patients’ survival. The addition of trastuzumab to the hormonal agent, anastrozole, was not associated with an increase of OS, despite an increase of 2.4 months in PFS, when compared with anastrazole monotherapy (Kaufman et al. [18]). The lapatinib plus letrozole combination increased PFS by 5 months when compared with letrozole monotherapy, but both regimens had similar OS (approximately 33 months) (Johnston et al. [17]). Adding carboplatin to trastuzumab and taxane did not extend OS and was associated with increased rates of neutropenia and thrombocytopenia (Robert et al. [19]; Valero et al. [22]). The BOLERO-1 trial showed that the addition of everolimus to trastuzumab and paclitaxel did not result in an improvement of PFS in patients with HER2+ advanced breast cancer (Hurwitz et al. [32]); a clinically important prolongation of PFS (7.2 months) was only seen with everolimus (versus placebo) when the analysis was restricted to hormone receptor-negative patients, but even so the p value did not achieved the prespecified criteria for statistical significance (Hurwitz et al. [32]). Further, everolimus was associated with an increased risk for serious adverse events, such as neutropenia, leucopenia, anemia, febrile neutropenia, stomatitis, and fatigue (Hurwitz et al. [32]). In all these studies evaluation of tolerability and quality of life is as relevant as efficacy results.

Dual HER2 inhibition with trastuzumab and pertuzumab, a HER2-targeted humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits dimerization, was more active than single inhibition with trastuzumab (Swain et al. [2]). This therapeutic combination prolonged patients’ survival, as well as PFS across all predefined subgroups. In the CLEOPATRA study, this led to an unprecedented PFS of 18 months and median OS of almost 5 years (Swain et al. [2]). Caution however is needed when extrapolating these results to current patient populations since only 10 % of patients from this trial had received prior chemotherapy with or without adjuvant or neoadjuvant trastuzumab.

HER2-targeted therapies have also demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of metastatic BC in the second-line setting. When compared to lapatinib plus capecitabine, T-DM1, an antibody-drug conjugate of trastuzumab and the chemotherapy drug DM1 (emtansine), extended the OS for almost 6 months in patients who had previously received trastuzumab and a taxane (Verma et al. [4]). Additionally, patients treated with T-DM1 experienced less toxicity. Similarly, the addition of everolimus to trastuzumab and vinorelbine in patients with trastuzumab-resistant and taxane-pretreated HER2+ advanced BC was associated with an improvement in PFS in this population. However, the addition of everolimus was associated with a high incidence of serious adverse events, exhibiting a similar safety profile to that seen in the BOLERO-1 trial (André et al. [23]). Beyond the second-line setting, a study demonstrated that treatment with dual HER2 blockade lapatinib plus trastuzumab improved OS when compared with lapatinib (Blackwell et al. [5]). However, treatment with lapatinib plus trastuzumab was associated with higher rates of treatment discontinuation and toxicity. More recently, the benefit of T-DM1, mainly on PFS, was also demonstrated in patients with HER2+ metastatic BC who have previously received trastuzumab and lapatinib (Krop et al. [27]).

Patients treated with trastuzumab have higher risk of cardiotoxicity, mainly asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction or congestive heart failure (Slamon et al. [1]; Seidman et al. [34]). Congestive heart failure was detected as a safety signal late in the development of the drug (Seidman et al. [34]). Yet, the rates of cardiac dysfunction were greatest when trastuzumab was administered concomitantly with anthracyclines, and the most frequent events were asymptomatic declines in left ventricular ejection fraction (Seidman et al. [34]; Morris and Hudis [35]). Evidence suggests that trastuzumab’s cardiotoxicity is, however, uncommon and generally reversible (Morris and Hudis [35]; Procter et al. [36]; de Azambuja et al. [37]). In order to minimize the risk, all candidates for treatment with trastuzumab must undergo a baseline cardiac assessment, as well as regular (every 3 months) assessments during treatment, in particular those who have been previously exposed to anthracyclines or with risk factors for cardiac events. Despite this small cardiac iatrogenic potential, in the majority of patients with HER2+ metastatic BC, the risk of cardiac dysfunction is justified given the improvement in OS associated with trastuzumab (Seidman et al. [34]). Moreover, the most recently developed HER2-targeted therapeutic alternatives have been associated with relatively low rates of cardiovascular events (Verma et al. [4]).

Another safety issue is the, apparently, high rate of central nervous system metastases in patients receiving adjuvant trastuzumab, raising the question whether this treatment could predispose for central nervous system recurrence (Yin et al. [38]). A prospective, observational study of HER2+ metastatic BC patients concluded that the use of trastuzumab, chemotherapy, and surgery following central nervous system metastases were each associated with longer survival (Brufsky et al. [39]). Furthermore, a retrospective study found that anti-HER2 treatment is associated with longer time to occurrence of brain metastases when given before brain metastases diagnosis and with survival benefit when given after brain metastases (Yap et al. [40]). Findings from the CEREBREL clinical trial demonstrated no difference in the incidence of brain metastasis as a first site of progression between lapatinib plus capecitabine and trastuzumab plus capecitabine (Pivot et al. [28]). The most likely explanation for the data is that the beneficial effect of trastuzumab on systemic disease extends the survival of patients to such a degree that central nervous system metastases became clinically evident (Dawood et al. [41]; Yin et al. [38]).

In clinical practice different combinations than those evaluated in clinical trials may be used, assuming that the benefit of trastuzumab is the same regardless of its partner agent (Pegram et al. [42]; Pegram et al. [43]; Harris et al. [44]). Only a small number of HER2 combination therapies have been evaluated in RCTs, as it was noted in a previous meta-analysis (Harris et al. [44]), but it would be practically and economically unfeasible and unrealistic to perform a phase III trial to evaluate all possible combinations. It is now unethical to perform a study evaluating the addition of an anti-HER2 agent to a given cytotoxic or combination of cytotoxic agents versus not, the only design that would indeed assess the value of the different combinations. One can only compare between different combinations. Furthermore, the development of new anti-HER2 agents and the potential of dual or even triple blockade raises other possibly more relevant questions to test. The optimal sequencing of HER2-targeted therapies across multiple lines of treatment is of utmost importance due to the increasing number of available drugs (Verma et al. [4]).

There are several other studies evaluating different combinations of cytotoxic and anti-HER2 agents. However, such studies usually include a limited number of patients and do not report on OS. Therefore we chose to select only phase III RCTs since this design is less susceptible to bias, providing the highest level clinical and statistical evidence (Straus et al. [45]).

HER2-targeted therapies have an undeniable favorable impact in the outcome of patients with HER2+ metastatic BC. Integration of trastuzumab led to about 6 months benefit in OS. More recently, T-DM1 after trastuzumab led to a further 6 months benefit in OS. HER2 dual blockade with pertuzumab and trastuzumab is associated with a survival extension to more than 4.5 years (Swain et al. [2]). Since 2001, comparing the results of the clinical trial of Slamon and colleagues evaluating the addition of trastuzumab to chemotherapy, there has been an increase in OS of 2.5 years with anti-HER2 drugs (Slamon et al. [1]). Survival improvements have also been noted for the second- and third-line therapies. Once a poor prognosis disease, HER2+ advanced BC has now a wide range of therapeutic options that significantly increased the OS of patients and has become the subtype of metastatic BCs with the longest medium survival, similar to luminal breast cancers.

Abbreviations

- BC:

-

Breast cancer

- HER2+:

-

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive

- ITT:

-

intention-to-treat

- mBC:

-

Metastatic breast cancer

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- RCTs:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- T-DM1:

-

Trastuzumab emtansine

References

Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783–92.

Swain SM, Kim SB, Cortés J, Ro J, Semiglazov V, Campone M, et al. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (CLEOPATRA study): overall survival results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:461–71.

Cameron D, Casey M, Press M, Lindquist D, Pienkowski T, Romieu CG, et al. A phase III randomized comparison of lapatinib plus capecitabine versus capecitabine alone in women with advanced breast cancer that has progressed on trastuzumab: updated efficacy and biomarker analyses. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112:533–43.

Verma S, Miles D, Gianni L, Krop IE, Welslau M, Baselga J, et al. Trastuzumab emtansine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1783–91.

Blackwell KL, Burstein HJ, Storniolo AM, Rugo HS, Sledge G, Aktan G, et al. Overall survival benefit with lapatinib in combination with trastuzumab for patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer: final results from the EGF104900 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2585–92.

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr. Accessed on 28 May 2014.

Dawood S, Broglio K, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH. Prognosis of women with metastatic breast cancer by HER2 status and trastuzumab treatment: an institutional-based review. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:92–8.

Cardoso F, Costa A, Norton L, Senkus E, Aapro M, André F, et al. ESO-ESMO 2nd international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC2)†. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1871–88.

Tandon AK, Clark GM, Chamness GC, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. HER-2/neu oncogene protein and prognosis in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1120–8.

Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235:177–82.

Food and Drug Administration. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research and Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Guidance for Industry Clinical Trial Endpoints for the Approval of Cancer Drugs and Biologics. Bethesda, MD: 2007. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm071590.pdf. Accessed on 28 May 2014.

Andersson M, Lidbrink E, Bjerre K, Wist E, Enevoldsen K, Jensen AB, et al. Phase III randomized study comparing docetaxel plus trastuzumab with vinorelbine plus trastuzumab as first-line therapy of metastatic or locally advanced human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: the HERNATA study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:264–71.

Baselga J, Cortés J, Kim SB, Im SA, Hegg R, Im YH, et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:109–19.

Baselga J, Manikhas A, Cortés J, Llombart A, Roman L, Semiglazov VF, et al. Phase III trial of nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin in combination with trastuzumab and paclitaxel in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:592–8.

Guan Z, Xu B, DeSilvio ML, Shen Z, Arpornwirat W, Tong Z, et al. Randomized trial of lapatinib versus placebo added to paclitaxel in the treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1947–53.

Inoue K, Nakagami K, Mizutani M, Hozumi Y, Fujiwara Y, Masuda N, et al. Randomized phase III trial of trastuzumab monotherapy followed by trastuzumab plus docetaxel versus trastuzumab plus docetaxel as first-line therapy in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: the JO17360 Trial Group. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119:127–36.

Johnston S, Pippen Jr J, Pivot X, Lichinitser M, Sadeghi S, Dieras V, et al. Lapatinib combined with letrozole versus letrozole and placebo as first-line therapy for postmenopausal hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5538–46.

Kaufman B, Mackey JR, Clemens MR, Bapsy PP, Vaid A, Wardley A, et al. Trastuzumab plus anastrozole versus anastrozole alone for the treatment of postmenopausal women with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive, hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer: results from the randomized phase III TAnDEM study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5529–37.

Robert N, Leyland-Jones B, Asmar L, Belt R, Ilegbodu D, Loesch D, et al. Randomized phase III study of trastuzumab, paclitaxel, and carboplatin compared with trastuzumab and paclitaxel in women with HER-2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2786–92.

Schwartzberg LS, Franco SX, Florance A, O’Rourke L, Maltzman J, Johnston S. Lapatinib plus letrozole as first-line therapy for HER-2+ hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist. 2010;15:122–9.

Swain SM, Baselga J, Kim SB, Ro J, Semiglazov V, Campone M, et al. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:724–34.

Valero V, Forbes J, Pegram MD, Pienkowski T, Eiermann W, von Minckwitz G, et al. Multicenter phase III randomized trial comparing docetaxel and trastuzumab with docetaxel, carboplatin, and trastuzumab as first-line chemotherapy for patients with HER2-gene-amplified metastatic breast cancer (BCIRG 007 study): two highly active therapeutic regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:149–56.

André F, O’Regan R, Ozguroglu M, Toi M, Xu B, Jerusalem G, et al. Everolimus for women with trastuzumab-resistant, HER2-positive, advanced breast cancer (BOLERO-3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:580–91.

Blackwell KL, Burstein HJ, Storniolo AM, Rugo H, Sledge G, Koehler M, et al. Randomized study of Lapatinib alone or in combination with trastuzumab in women with ErbB2-positive, trastuzumab-refractory metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1124–30.

Cameron D, Casey M, Oliva C, Newstat B, Newstat B, Imwalle B, et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine in women with HER-2-positive advanced breast cancer: final survival analysis of a phase III randomized trial. Oncologist. 2010;15:924–34.

Geyer CE, Forster J, Lindquist D, Chan S, Romieu CG, Pienkowski T, et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2733–43.

Krop IE, Kim SB, González-Martín A, LoRusso PM, Ferrero JM, Smitt M, et al. Trastuzumab emtansine versus treatment of physician’s choice for pretreated HER2-positive advanced breast cancer (TH3RESA): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:689–99.

Pivot X, Manikhas A, Żurawski B, Chmielowska E, Karaszewska B, Allerton R, et al. CEREBEL (EGF111438): a phase III, randomized, open-label study of lapatinib plus capecitabine versus trastuzumab plus capecitabine in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1564–73.

von Minckwitz G, du Bois A, Schmidt M, Maass N, Cufer T, de Jongh FE, et al. Trastuzumab beyond progression in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive advanced breast cancer: a German Breast Group 26/Breast International Group 03–05 study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1999–2006.

von Minckwitz G, Schwedler K, Schmidt M, Barinoff J, Mundhenke C, Cufer T, et al. Trastuzumab beyond progression: overall survival analysis of the GBG 26/BIG 3–05 phase III study in HER2-positive breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2273–81.

Gelmon KA, Boyle FM, Kaufman B, Huntsman DG, Manikhas A, Di Leo A, et al. Lapatinib or trastuzumab plus taxane therapy for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive advanced breast cancer: final results of NCIC CTG MA.31. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1574–83.

Hurvitz SA, Andre F, Jiang Z, Shao Z, Mano MS, Neciosup SP, et al. Combination of everolimus with trastuzumab plus paclitaxel as first-line treatment for patients with HER2-positive advanced breast cancer (BOLERO-1): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:816–29.

Chia SK, Speers CH, D’yachkova Y, Kang A, Malfair-Taylor S, Barnett J, et al. The impact of new chemotherapeutic and hormone agents on survival in a population-based cohort of women with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:973–9.

Seidman A, Hudis C, Pierri MK, Shak S, Paton V, Ashby M, et al. Cardiac dysfunction in the trastuzumab clinical trials experience. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1215–21.

Morris PG, Hudis CA. Optimizing dose-dense regimens for early-stage breast cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7:678–9.

Procter M, Suter TM, de Azambuja E, Dafni U, van Dooren V, Muehlbauer S, et al. Longer-term assessment of trastuzumab-related cardiac adverse events in the Herceptin Adjuvant (HERA) trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3422–8.

de Azambuja E, Procter MJ, van Veldhuisen DJ, Agbor-Tarh D, Metzger-Filho O, Steinseifer J, et al. Trastuzumab-associated cardiac events at 8 years of median follow-up in the herceptin adjuvant trial (BIG 1–01). J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2159–65.

Yin W, Jiang Y, Shen Z, Shao Z, Lu J. Trastuzumab in the adjuvant treatment of HER2-positive early breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis of published randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21030.

Brufsky AM, Mayer M, Rugo HS, Kaufman PA, Tan-Chiu E, Tripathy D, et al. Central nervous system metastases in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: incidence, treatment, and survival in patients from registHER. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4834–43.

Yap YS, Cornelio GH, Devi BC, Khorprasert C, Kim SB, Kim TY, et al. Brain metastases in Asian HER2-positive breast cancer patients: anti-HER2 treatments and their impact on survival. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1075–82.

Dawood S, Broglio K, Esteva FJ, Ibrahim NK, Kau SW, Islam R, et al. Defining prognosis for women with breast cancer and CNS metastases by HER2 status. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1242–8.

Pegram M, Hsu S, Lewis G, Pietras R, Beryt M, Sliwkowski M, et al. Inhibitory effects of combinations of HER-2/neu antibody and chemotherapeutic agents used for treatment of human breast cancers. Oncogene. 1999;18:2241–51.

Pegram MD, Konecny GE, O’Callaghan C, Beryt M, Pietras R, Slamon DJ. Rational combinations of trastuzumab with chemotherapeutic drugs used in the treatment of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:739–49.

Harris CA, Ward RL, Dobbins TA, Drew AK, Pearson S. The efficacy of HER2-targeted agents in metastatic breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1308–17.

Straus ES, Glasziou P, Richardson WS, Haynes RB. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. 4th ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2011. p. 125–8.

Funding This work was financially supported by Roche Farmacêutica Química, Lda (Portugal).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

DM and CA conceived the study, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote and reviewed the paper. FBM conceived the study, analyzed the data, wrote and reviewed the paper. NA, FC, JLPC, LC and SA reviewed the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Search strategies used to retrieve randomized controlled trials from the Cochrane Library and PubMed (Updated, 6 October 2015). (DOCX 12 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mendes, D., Alves, C., Afonso, N. et al. The benefit of HER2-targeted therapies on overall survival of patients with metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer – a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res 17, 140 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-015-0648-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-015-0648-2