Abstract

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are a newly discovered class of endogenous non-coding RNAs that play an important role in growth and development by regulating gene expression and participating in a variety of biological processes. However, the role of circRNAs in porcine follicles remains unclear. Therefore, this study examined middle-sized ovarian follicles obtained from Meishan and Duroc sows at day 4 of the follicular phase. High-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was utilized to construct circRNAs, and differential expression was identified. The findings were validated using reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) and DNA sequencing, GO and KEGG analyses were performed, and potential miRNA targets were identified. The RNA-seq identified a total of 15,866 circRNAs, with 244 differentially expressed in the Meishan relative to the Duroc (111 up-regulated and 133 down-regulated). The RT-PCR finding confirmed the RNA-seq results, and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis examining a subset of the circRNAs showed that they are resistant to RNase R digestion. Bioinformatics analysis (GO and KEGG) showed that the host genes associated with the differentially expressed circRNAs are involved in reproduction and follicular development signaling pathways. Furthermore, many of the circRNAs were found to interact with miRNAs that are associated with follicular development. This study presents a new perspective for studying circRNAs and provides a valuable resource for further examination into the potential roles of circRNAs in porcine follicular development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For the past few years, circular RNAs (circRNAs) have attracted attention as a new member of the noncoding RNA family in animals [1,2,3]. In 1976, Sanger et al. first discovered that certain higher plant viruses were covalently closed circular RNA molecules [4]. Then in 1986, Kos et al. discovered that the hepatitis delta virus (HDV) genome comprises circRNA [5]. In recent years, breakthroughs in high-throughput deep sequencing technology have identified circRNAs in humans [3, 6, 7], mice [6, 7], nematodes [7, 8] and coelacanths [9]. Furthermore, studies have shown that circRNAs exhibit specific expression patterns in different tissues or cell types and at different developmental stages [3, 7]. The richness and diversity of circRNA expression may be related to the alternative splicing of RNA transcripts. Moreover, circRNA formation is facilitated by the complementary pairing between repeated intron sequences on both sides of axons [10,11,12,13]. Recent circRNA studies have shown that circRNAs possess structural diversity, a high abundance, and a high resistance to exonuclease or RNase degradation, are highly conserved, and have cell or tissue specific expression [13,14,15].

However, few studies have examined the regulation of circRNAs in association with animal reproduction. When examining ovary, testis, and placental circRNA expression patterns, studies have suggested a role in regulating the reproductive system and embryo development [16,17,18,19]. In a study performing transcriptome analysis of mouse germline cells, 18,822 circRNAs were identified, with 921 being sex related [20]. In another study examining differential circRNA expression in placenta tissues in pregnant women with preeclampsia (PE), a total of 143 up-regulated and 158 down-regulated circRNAs were identified [17]. Additionally, recent evidence suggests that circRNAs are involved in a wide range of biological processes and function as competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNA) [21, 22]. During the cell cycle, circular RNA FoxO3 interacts with CKD2 (cyclin-dependent protein kinase 2) to stop the cell cycle progression during the G1/S phase [23]. CircRNAs have also been shown to regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level by binding to micro-RNAs (miRNAs), with cdr1as shown to act as a potent miRNA sponge that binds mir-7 and facilitates mRNA preservation [23, 24].

In the swine industry, sow productivity is one of the most important factors affecting the production efficiency. The main factor that limits litter size is the ovulation rate, with a higher ovulation rate contributing to a larger litter size. In China, the Meishan breed, a sub-group of the Taihu pig, provides sows with larger litter sizes relative to Durocs and is known for its high fecundity. In a previous study, differences in follicular growth dynamics between prolific Meishan sows and ordinary sows were found to occur during the mid-to-late-follicular phase and greatly contributed to the high ovulation rate [25]. Furthermore, another study suggested that there are significant differences in middle-size ovarian follicle growth regulation and physiological development between Meishan and Duroc sows [26]. Additionally, circRNAs have been examined in other organisms, including Drosophila ovarian tissue [27], goat ovarian follicles prior to ovulation [28], and honeybee ovaries in association with activation and spawning [29]. However, circRNAs have not been examined in association with porcine follicular development. Therefore, this study utilized RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to explore circRNA differential expression during follicular development in Meishan and Duroc pigs. It is hoped that the results of this study will provide insight into the potential function of circRNA in porcine follicular development and aid in identifying circRNAs that are key to this process.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

All procedures involving animals were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Shihezi University (Shihezi, China) and were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards established in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

Tissue sample collection

Meishan sows (n = 3) were obtained from Yangzhou University (Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China), and Duroc sows (n = 3) were obtained from Tiankang Animal Husbandry Co., Ltd. (Xinjiang, China). All multiparous sows showed a normal estrus and reproductive performance in accordance with their breed characteristics. A day 14 of estrus, veterinary chloroprostol (0.2 mg/per pig) was injected along the ear vein, and the sows were subsequently slaughtered 4 days later. The M2 follicles (~ 5.0–6.9 mm in diameter) were collected and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNAs were isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and RNA quantity and purity were assessed using a RNA6000 Nano Kit and Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, CA, USA).

RNA-seq and quality control

Prior to RNA-seq, ribosomal RNA was removed from each individual sample (3 μg) using an Epicentre Ribo-Ribo-zero™ rRNA Removal Kit (Epicentre, USA), followed by ethanol precipitation to clean-up the rRNA free residue. Sequencing libraries were then generated using the rRNA-depleted RNA and a NEBNext® Ultra™ Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (NEB, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly, fragmentation was carried out in NEBNext First Strand Synthesis Reaction Buffer (5X) using divalent cations under an elevated temperature. First strand cDNA synthesis was performed using random hexamer primers and M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (RNaseH), and second strand synthesis was performed using DNA Polymerase I and RNase H, with remaining overhangs converted to blunt ends. For the dNTPs in the reaction buffer, dTTPs were replaced with dUTPs. After performing polyadenylation, a NEBNext Adaptor with hairpin loop structure was ligated to prepare for hybridization. To select cDNA fragments of a preferred length (~ 150–200 bp), the library fragments were purified using an AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter, Beverly, MA, USA). The obtained size-selected, adaptor-ligated cDNA was then combined with 3 μl USER Enzyme (NEB) at 37 °C for 15 min, followed by 5 min at 95 °C. The PCR reaction was then performed with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (NEB), Universal PCR primers, and Index (X) Primer. Finally, the PCR products were purified (AMPure XP system) and the library quality was assessed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. Index-coded samples were clustered using a TruSeq PE Cluster Kit v3-cBot-HS (Illumia, San Diego, CA, USA) with a cBot Cluster Generation System according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The libraries were then sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq 2500 platform, and 125 bp paired-end reads were generated. Raw data (raw reads) were obtained in FASTQ format and were preliminarily processed through an in-house perl script. In this step, clean reads were obtained by removing reads containing adapters or ploy-N and by removing low quality reads. Next, Q20, Q30, and GC contents were calculated for the clean reads, and all downstream analyses were performed using this high-quality clean data.

CircRNA identification

Reference genome and gene model annotation files were downloaded directly from the genome website (http:/genome.ucsc.edu/). An index for the reference genome was built using bowtie v2.2.8, and paired-end clean reads were aligned to the reference genome using TopHat v2.0.9. The circRNAs were detected and identified using find_circ [7]. The basic principle of find_circ is to extract a 20 nt anchor sequence from each end of a given read without comparison to the reference sequence, and then compare each pair of anchor sequences to the reference sequence. A read was determined to be a candidate circRNA if the 5′ end of the anchor sequence was aligned to the reference sequence (the start and stop sites are labeled A3 and A4, respectively), if the 3′ end of the anchor sequence was aligned upstream of that site (the start and stop sites are labeled A1 and A2, respectively), and if a splice site (GT-AG) existed between A2 and A3 in the reference sequence. Finally, a candidate circRNA was confirmed as a circRNA if the read count is greater than or equal to 2

Analysis of differentially expressed circRNAs

The raw counts were first normalized using TPM (transcripts-per-million clean tags) [30], and differential expression analysis was performed using the R package DESeq (1.10.1). DESeq provides statistical routines for determining differential expression for digital gene expression data using a model based on the negative binomial distribution. CircRNAs with a p < 0.05 and |log2 (fold change)| > 1.5 were considered significantly differentially expressed.

Target site prediction and enrichment analysis

MicroRNA target sites were identified within the exons of circRNA loci and were identified using miRanda and psRobot. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was employed to characterize the host genes of the differentially expressed circRNAs using DAVID [31]. GO terms with a corrected p-value less than 0.05 were considered significantly enriched. Differential gene expression and circRNA host genes were further examined using KEGG pathway analysis, and statistical enrichment was determined using KOBAS [32]. Findings were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05 was obtained.

Reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) analysis and sequencing

Total RNAs were extracted from the sow ovarian follicles using TRIzol (Invitrogen, CA, USA), and cDNA was synthesized using a RT-PCR kit (Takara, Dalian, China). The PCR reaction was conducted using specific primers for circ_0012855, circ_0001712, circ_0015292, circ_0001651, circ_0008449, circ_0012124, circ_0000058, circ_0003666, circ_0010513, and circ_0011249 (Table 1). The PCR products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis, and a direct gene sequence analysis was performed. The PCR product sequences were then compared with the Sus scrofa reference genome and the RNA-seq data using DNAMAN software. The PCR reaction was conducted by combining 10 μL of premix (Takara, Dalian, China), 1 μL of cDNA template, 0.6 μL each of upstream and downstream primers, and 7.8 μL of RNase-free ddH2O water. RT-PCR was performed as follows: an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 45 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, Tm (°C) for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis

The expression levels of four circRNAs (circ_0015292, circ_0001651, circ_0012124, and circ_0010513) were detected via qPCR analysis, with GAPDH used as an internal reference gene [33]. To determine the resistance of circRNAs to RNase R digestion, total RNAs were treated with RNase R (RNR-07250; Epicentre) prior to cDNA synthesis. To validate differentially expressed circRNAs, total RNAs were directly subjected to cDNA synthesis using a RT-PCR kit (Takara, Dalian, China). Reactions were performed using SYBR Green I (TaKaRa Biotech, Dalian) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and circRNA expression levels were normalized to linear GAPDH levels. Three independent experiments were performed using triplicate samples. The qPCR reaction was conducted by combining 10 μL of SYBR Premix DimerEraser (Takara, Dalian, China), 1 μL of cDNA, 0.6 μL each of the upstream and downstream primers, and 7.8 μL of RNase-free ddH2O water. The qPCR reaction was performed as follows: an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 300 s, followed by 45 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, Tm (°C) for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s.

Results

High-throughput sequencing of porcine ovarian follicle circRNAs

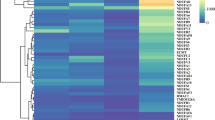

To determine circRNA identities and abundances in intermediate porcine follicles obtained from Meishan and Duroc pigs, RNA-seq was performed (Fig. 1a) and circRNAs within the two libraries were identified using the find_circ program [7]. A total of 15,866 circRNAs were identified between the two groups and were found to consist of introns, exons, and a small number of intergenic sequences (Fig. 1b). Additionally, circRNA annotations, chromosomal locations, and host mRNA were also determined, with the top 25 up- and down-regulated circRNAs also identified based on log2FC values (Table 2).

Validation of circRNAs using RT-PCR

To further validate the RNA-seq findings, RT-PCR was employed and specific primers were designed to reverse amplify the circRNA junctions (Fig. 2). For the 10 randomly selected circRNAs, the head-to-tail junction sites were quantified via RT-PCR analysis and confirmed using DNA sequencing (Fig. 3). Additionally, the resistance of the circRNAs to RNase R digestion was also examined using qPCR. All of the examined circRNAs were found to be RNase R resistant, while the internal control, GAPDH, was not detected (sensitive to RNase R; Fig. 4).

Verification and analysis of differentially expressed circRNA

Further analysis confirmed the 244 differentially expressed middle follicle circRNAs, 111 up-regulated and 133 down-regulated, in Meishan sows relative to Duroc sows (Fig. 5a). Many of the circRNAs were distributed across various chromosomes, with many located on chromosome 1 (Fig. 5b). Next, four differentially expressed circRNAs were selected, and their expression levels were quantified via qPCR. The results showed in Meishan follicle samples that circ_0001651 and circ_0010513 expression is up-regulated relative to Duroc samples, while circ_0015292 and circ_0012124 expression is down-regulated (Fig. 5d). These findings are consistent with the RNA-seq findings and confirm that the sequencing results are accurate and reliable (Fig. 5e).

Analysis and validation of differentially expressed circRNAs in Meishan ovarian follicle samples relative to Duroc samples. a Volcano plot demonstrating a distinguishable circRNA expression pattern between Meishan and Duroc ovarian follicles; b Circos plot displaying circRNA chromosomal distributions; c Circos plot displaying differentially expressed circRNA chromosomal distributions; d Relative expression levels of a subset of four circRNAs; e Comparison of qPCR and RNA-seq results confirms a high degree of consistency

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of differentially expressed circRNA host genes

In previous studies, circRNAs have been shown to regulate the expression of their host genes [34,35,36], and their functions may relate to those of their host genes. Therefore, GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was performed using the host genes associated with the differentially expressed circRNA. GO analysis identified 201 significantly enriched terms within the biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components groups. The top 20 GO terms were associated with several functional categories, including metabolic processes, intracellular protease complexes, and enzymatic activity (Fig. 6), thus indicating that some circRNAs are involved in the basic biological regulation of porcine follicular development. The KEGG pathway analysis enriched 87 pathways (Fig. 6e), including PI3K-Akt, oocyte meiosis, and TGFβ-SMAD signaling pathways that are involved in follicular granulosa cell growth regulation. These results indicate that circRNAs play an important role in the formation and development of porcine follicles.

Porcine follicle circRNA functional predictions

Previous studies have suggested that circRNAs can act as a miRNA sponge, thereby affecting the expression of miRNA target genes [2, 24, 37, 38]. Herein, miRanda and psRobot software were used to analyze potential interactions between circRNAs and miRNAs, with 1,925,007 potential interactions identified between 15,866 circRNAs and various miRNAs. Moreover, it is worth noting that some of the known miRNAs are closely related to follicular development and are considered prospects for future research. The circRNAs examined in this study were found to contain multiple conserved binding sites for miRNAs, such as miR-21, miR-144, or miR-181-a, which indicated that circRNAs are involved in follicular development (Fig. 7). To elucidate the functional roles of the examined circRNAs in association with miRNAs, circRNA target miRNAs and downstream regulated mRNAs were predicted, and a basic circRNA-miRNA-mRNA connective network was established (Fig. 8). The results indicated that porcine follicular growth and development are likely to be affected by circRNAs.

Discussion and conclusions

CircRNAs are a new class of endogenous non-coding RNAs that were once considered a by-product of splicing errors but have been found to be widely expressed in human cells and function in many biological processes [7, 39]. Furthermore, studies have shown that circRNAs are involved in regulation [40,41,42] and can be associated with diseases, including cancer [43, 44]. CircRNAs are highly conserved and very stable, contain tissue-specific sequences, and contain unique ceRNA features [2, 24, 45]. Moreover, studies have suggested that human and mouse early embryos have a high degree of similarity in relevant biological processes where circRNA host genes appear to be primary factors [19, 46]. Among different species, most circRNA expressions are highly conserved [45, 47], with abnormal circRNA expression associated with many human diseases, such as cancer, nervous system diseases, and cardiovascular diseases [21, 43, 48, 49]. In ovarian cancer cells, the up-regulation of hsa-circ-0061140 promotes EMT, cell proliferation, and migration [50]. However, when it comes to livestock, especially swine, reproduction-associated circRNA expression remains unclear. Thus, this study focused on exploring the potential role of circRNAs in porcine follicle development. First, RNA-seq was utilized to establish follicular circRNA profiles for Meishan and Duroc sows. A total of 15,866 circRNAs were identified, with 244 being differentially expressed (111 up-regulated and 133 down-regulated).

At present, research focused on examining the regulation of circRNAs in animal reproduction has been making small gains year by year. To improve the reproductive capacity in sows, it is important to more fully characterize the follicles and the factors that influence them. During oocyte maturation and early embryo development, granulocytes (GCs) are very important, and follicular atresia results in granulosa cell apoptosis [51, 52]. Dicer is a conserved ribonuclease and plays a key role in regulating oocyte development in mice [53]. Furthermore, mir-145 can inhibit the proliferation of mouse granulosa cells by targeting a gene called activin receptor IB (ACVR1B) [54]. In a previous study examining human GCs, circRNA_104816 and circRNA_103827 were found to potentially serve as biomarkers indicating follicular microenvironment damage, with their up-regulation being closely associated with a decreased ovarian reserve and poor reproductive outcomes [55]. Furthermore, in another study examining goat pre-ovulatory follicles, 37 differentially expressed circRNAs were identified, with chi-circ 0008219 found to regulate follicular growth by modulating three miRNAs [28]. Based on the above results, we hypothesized that circRNAs may serve as novel regulators of ovarian follicle growth and development during porcine reproduction.

Some studies have shown that circRNAs can modulate miRNAs by acting as a miRNA sponge [7, 24, 56]. In cancers, CDR1as has been shown to act as a sponge for mir-7 and subsequently suppresses its activity and promotes tumor development [57]. Moreover, testis-specific sex-determining region Y (SRY) 9 acts as a sponge for mir-138 and contains 16 mir-138 binding sites, thus reducing its effects [24, 58]. Herein, miRanda and PSrobot were used to predict miRNA target sites within the identified porcine follicular circRNAs. Of the identified miRNA interactions, miR-191, miR-210, miR-132, miR-370, and miR-181-a were found to be associated with follicular development. Furthermore, the results showed that a single circRNA has different target binding sites for different miRNAs. One of the circRNAs, ssc-circ-0001651, was found to contain 18 potential binding sites for 8 different miRNAs associated with follicular granule cell development (partial results only), including let-7 g (3 target sites), miR-21 (1 target site), miR − 224 (1 target site), miR-10b (4 target sites), miR-16 (4 target sites), miR-106a (1 target site), miR-19b (2 targets sites), and miR-31 (2 target sites). For ssc-circ-0015292, 8 target sites were identified (partial results only) that bind miR-34a (1 target site), miR-144 (1 target site), miR-320 (1 target site), miR-181a (1 target site), miR-150 (1 target site), miR-23a (2 target sites), and miR-27a (1 target site). Therefore, these findings suggest that ssc_circ_0001651 and ssc_circ_0015292 can act as potential ceRNAs, which would make them newly identified porcine ovarian follicular development regulators, but further investigation is required.

In addition to regulating gene expression, circRNAs have also been shown to serve other functions. Recent studies have indicated that circRNAs can direct protein synthesis via mRNA modulation, and a few of them may be converted to proteins via an IRES (internal ribosome entry site) insertion [59, 60]. Several factors and pathways are known to be involved in follicular growth and development, including follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), insulin growth factor (IGF), and transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) and their related receptor-mediated signaling pathways, including PI3K-Akt, Wnt/β-catenin, and TGFβ-SMAD signaling pathways. Furthermore, Tao et al. reported that prior to goat ovulation, the host genes of ovarian follicle circRNAs participate in ovarian corpus callosum generation pathways and p53 signaling [28]. CircRNA host genes have also been implicated in the production of ovarian steroids and their mediated signals that are critical for biological processes such as follicular growth, oocyte maturation, and ovulation [61].

Conclusions

In this study, GO and KEGG pathway annotations identified important biological processes and pathways, including metabolic processes, enzyme activity regulation, endocytosis, steroid hormone biosynthesis, cell cycle and cell adhesion, and homologous recombination. Moreover, important signaling pathways, such as TGF-β, p53, insulin, oocyte meiosis, and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways, were enriched. Collectively, these findings suggest that circRNAs can affect the development of porcine follicles by modulating associated pathways.

In summary, ovarian follicle circRNA profiles were obtained for Meishan and Duroc sows, with differentially expressed circRNAs also identified. GO and KEGG analyses were then utilized to elucidate the roles of the identified differential circRNAs, with several found to be involved in ovarian follicle growth and development regulation. This study provides further insight into the mechanisms of porcine follicle development and the roles of circRNAs.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets and supporting conclusions are included within this manuscript or its supporting files. The datasets generated during this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Lasda E, Parker R. Circular RNAs: diversity of form and function. Rna. 2014;20(12):1829–42. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.047126.114.

Jeck WR, Sharpless NE. Detecting and characterizing circular RNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(5):453–61. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2890.

Salzman J, Chen RE, Olsen MN, Wang PL, Brown PO. Cell-type specific features of circular RNA expression. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(9):e1003777. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003777.

Sanger HL, Klotz G, Riesner D, Gross HJ, Kleinschmidt AK. Viroids are single-stranded covalently closed circular RNA molecules existing as highly base-paired rod-like structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73(11):3852–6. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.73.11.3852.

Kos A, Dijkema R, Arnberg AC, van der Meide PH, Schellekens H. The hepatitis delta (delta) virus possesses a circular RNA. Nature. 1986;323(6088):558–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/323558a0.

Rybak-Wolf A, Stottmeister C, Glazar P, Jens M, Pino N, Giusti S, Hanan M, Behm M, Bartok O, Ashwal-Fluss R, et al. Circular RNAs in the mammalian brain are highly abundant, conserved, and dynamically expressed. Mol Cell. 2015;58(5):870–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2015.03.027.

Memczak S, Jens M, Elefsinioti A, Torti F, Krueger J, Rybak A, Maier L, Mackowiak SD, Gregersen LH, Munschauer M, et al. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature. 2013;495(7441):333–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11928.

Ivanov A, Memczak S, Wyler E, Torti F, Porath HT, Orejuela MR, Piechotta M, Levanon EY, Landthaler M, Dieterich C, et al. Analysis of intron sequences reveals hallmarks of circular RNA biogenesis in animals. Cell Rep. 2015;10(2):170–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.019.

Nitsche A, Doose G, Tafer H, Robinson M, Saha NR, Gerdol M, Canapa A, Hoffmann S, Amemiya CT, Stadler PF. Atypical RNAs in the coelacanth transcriptome. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2014;322(6):342–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.b.22542.

Barrett SP, Salzman J. Circular RNAs: analysis, expression and potential functions. Development. 2016;143(11):1838–47. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.128074.

Barrett SP, Wang PL, Salzman J. Circular RNA biogenesis can proceed through an exon-containing lariat precursor. eLife. 2015;4:e07540. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.07540\.

Schindewolf C, Braun S, Domdey H. In vitro generation of a circular exon from a linear pre-mRNA transcript. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24(7):1260–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/24.7.1260.

Starke S, Jost I, Rossbach O, Schneider T, Schreiner S, Hung LH, Bindereif A. Exon circularization requires canonical splice signals. Cell Rep. 2015;10(1):103–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.002.

Chen I, Chen CY, Chuang TJ. Biogenesis, identification, and function of exonic circular RNAs. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2015;6(5):563–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/wrna.1294.

Salzman J, Circular RNA. Expression: its potential regulation and function. Trends Genet. 2016;32(5):309–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2016.03.002.

Dong WW, Li HM, Qing XR, Huang DH, Li HG. Identification and characterization of human testis derived circular RNAs and their existence in seminal plasma. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39080. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep39080.

Qian Y, Lu Y, Rui C, Qian Y, Cai M, Jia R. Potential significance of Circular RNA in human placental tissue for patients with preeclampsia. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;39(4):1380–90. https://doi.org/10.1159/000447842 Epub 2016 Sep 8. PMID: 27606420.

Wang LP, Peng XY, Lv XQ, Liu L, Li XL, He X, Lv F, Pan Y, Wang L, Liu KF, et al. High throughput circRNAs sequencing profile of follicle fluid exosomes of polycystic ovary syndrome patients. J Cell Physiol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.28201.

Dang Y, Yan L, Hu B, Fan X, Ren Y, Li R, Lian Y, Yan J, Li Q, Zhang Y, et al. Tracing the expression of circular RNAs in human pre-implantation embryos. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-0991-3.

Li X, Ao J, Wu J. Systematic identification and comparison of expressed profiles of lncRNAs and circRNAs with associated co-expression and ceRNA networks in mouse germline stem cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8(16):26573–90. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.15719.

Hansen TB, Kjems J, Damgaard CK. Circular RNA and miR-7 in cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73(18):5609–12. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1568.

Wang K, Long B, Liu F, Wang JX, Liu CY, Zhao B, Zhou LY, Sun T, Wang M, Yu T, et al. A circular RNA protects the heart from pathological hypertrophy and heart failure by targeting miR-223. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(33):2602–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv713.

Du WW, Yang W, Liu E, Yang Z, Dhaliwal P, Yang BB. Foxo3 circular RNA retards cell cycle progression via forming ternary complexes with p21 and CDK2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(6):2846–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw027.

Hansen TB, Jensen TI, Clausen BH, Bramsen JB, Finsen B, Damgaard CK, Kjems J. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature. 2013;495(7441):384–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11993.

Miller AT, Picton HM, Craigon J, Hunter MG. Follicle dynamics and aromatase activity in high-ovulating Meishan sows and in large-white hybrid contemporaries. Biol Reprod. 1998;58(6):1372–8. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod58.6.1372.

Ma L-P, Zhao Z-C, Li T, Li D-Q, Wang X-Y, Song C-Y, Qi Y-Y, Huang T. Identification of differentially expressed microRNAs in middle-size ovarian follicles of Meishan and Duroc sows. Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia. 2019;48:e20170326. Epub. https://doi.org/10.1590/rbz4820170326.

Westholm JO, Miura P, Olson S, Shenker S, Joseph B, Sanfilippo P, Celniker SE, Graveley BR, Lai EC. Genome-wide analysis of drosophila circular RNAs reveals their structural and sequence properties and age-dependent neural accumulation. Cell Rep. 2014;9(5):1966–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.062.

Tao H, Xiong Q, Zhang F, Zhang N, Liu Y, Suo X, Li X, Yang Q, Chen M. Circular RNA profiling reveals chi_circ_0008219 function as microRNA sponges in pre-ovulatory ovarian follicles of goats (Capra hircus). Genomics. 2017;S0888–7543(17):30129–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2017.10.005 Epub ahead of print. PMID: 29107014.

Chen X, Shi W, Chen C. Differential circular RNAs expression in ovary during oviposition in honey bees. Genomics. 2019;111(4):598–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2018.03.015.

Zhou L, Chen J, Li Z, Li X, Hu X, Huang Y, Zhao X, Liang C, Wang Y, Sun L, et al. Integrated profiling of microRNAs and mRNAs: microRNAs located on Xq27.3 associate with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. PloS one. 2010;5(12):e15224. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0015224.

Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(1):44–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2008.211.

Mao X, Cai T, Olyarchuk JG, Wei L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics (Oxford). 2005;21(19):3787–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bti430.

Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3(7):RESEARCH0034. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034 Epub 2002 Jun 18. PMID: 12184808; PMCID: PMC126239.

Huang C, Shan G. What happens at or after transcription: insights into circRNA biogenesis and function. Transcription. 2015;6(4):61–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/21541264.2015.1071301.

Li Z, Huang C, Bao C, Chen L, Lin M, Wang X, Zhong G, Yu B, Hu W, Dai L, et al. Exon-intron circular RNAs regulate transcription in the nucleus. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22(3):256–64. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2959.

Zhang Y, Zhang XO, Chen T, Xiang JF, Yin QF, Xing YH, Zhu S, Yang L, Chen LL. Circular intronic long noncoding RNAs. Mol Cell. 2013;51(6):792–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.017.

Zheng Q, Bao C, Guo W, Li S, Chen J, Chen B, Luo Y, Lyu D, Li Y, Shi G, et al. Circular RNA profiling reveals an abundant circHIPK3 that regulates cell growth by sponging multiple miRNAs. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11215. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11215.

Dudekula DB, Panda AC, Grammatikakis I, De S, Abdelmohsen K, Gorospe M. CircInteractome: a web tool for exploring circular RNAs and their interacting proteins and microRNAs. RNA Biol. 2016;13(1):34–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/15476286.2015.1128065.

Li Y, Zheng Q, Bao C, Li S, Guo W, Zhao J, Chen D, Gu J, He X, Huang S. Circular RNA is enriched and stable in exosomes: a promising biomarker for cancer diagnosis. Cell Res. 2015;25(8):981–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/cr.2015.82.

Li L, Guo J, Chen Y, Chang C, Xu C. Comprehensive CircRNA expression profile and selection of key CircRNAs during priming phase of rat liver regeneration. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-3476-6.

Conn SJ, Pillman KA, Toubia J, Conn VM, Salmanidis M, Phillips CA, Roslan S, Schreiber AW, Gregory PA, Goodall GJ. The RNA binding protein quaking regulates formation of circRNAs. Cell. 2015;160(6):1125–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.014.

Legnini I, Di Timoteo G, Rossi F, Morlando M, Briganti F, Sthandier O, Fatica A, Santini T, Andronache A, Wade M, Laneve P, Rajewsky N, Bozzoni I. Circ-ZNF609 is a Circular RNA that can be translated and functions in Myogenesis. Mol Cell. 2017;66(1):22–37.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2017.02.017.

Bachmayr-Heyda A, Reiner AT, Auer K, Sukhbaatar N, Aust S, Bachleitner-Hofmann T, Mesteri I, Grunt TW, Zeillinger R, Pils D. Correlation of circular RNA abundance with proliferation--exemplified with colorectal and ovarian cancer, idiopathic lung fibrosis, and normal human tissues. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8057. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08057.

Li P, Chen S, Chen H, Mo X, Li T, Shao Y, Xiao B, Guo J. Using circular RNA as a novel type of biomarker in the screening of gastric cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;444:132–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2015.02.018 Epub 2015 Feb 14. PMID: 25689795.

Jeck WR, Sorrentino JA, Wang K, Slevin MK, Burd CE, Liu J, Marzluff WF, Sharpless NE. Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. Rna. 2013;19(2):141–57. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.035667.112.

Fan X, Zhang X, Wu X, Guo H, Hu Y, Tang F, Huang Y. Single-cell RNA-seq transcriptome analysis of linear and circular RNAs in mouse preimplantation embryos. Genome Biol. 2015;16:148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-015-0706-1.

Salzman J, Gawad C, Wang PL, Lacayo N, Brown PO. Circular RNAs are the predominant transcript isoform from hundreds of human genes in diverse cell types. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30733. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0030733.

Floris G, Zhang L, Follesa P, Sun T. Regulatory role of Circular RNAs and neurological disorders. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(7):5156–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-016-0055-4.

Burd CE, Jeck WR, Liu Y, Sanoff HK, Wang Z, Sharpless NE. Expression of linear and novel circular forms of an INK4/ARF-associated non-coding RNA correlates with atherosclerosis risk. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(12):e1001233. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001233.

Chen Q, Zhang J, He Y, Wang Y. hsa_circ_0061140 Knockdown Reverses FOXM1-Mediated Cell Growth and Metastasis in Ovarian Cancer through miR-370 Sponge Activity. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2018, 13:55–63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2018.08.010.

Dumesic DA, Meldrum DR, Katz-Jaffe MG, Krisher RL, Schoolcraft WB. Oocyte environment: follicular fluid and cumulus cells are critical for oocyte health. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(2):303–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.11.015.

Moreno JM, Núñez MJ, Quiñonero A, Martínez S, de la Orden M, Simón C, Pellicer A, Díaz-García C, Domínguez F. Follicular fluid and mural granulosa cells microRNA profiles vary in in vitro fertilization patients depending on their age and oocyte maturation stage. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(4):1037–1046.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.07.001.

Murchison EP, Stein P, Xuan Z, Pan H, Zhang MQ, Schultz RM, Hannon GJ. Critical roles for dicer in the female germline. Genes Dev. 2007;21(6):682–93. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.1521307.

Yan G, Zhang L, Fang T, Zhang Q, Wu S, Jiang Y, Sun H, Hu Y. MicroRNA-145 suppresses mouse granulosa cell proliferation by targeting activin receptor IB. FEBS Lett. 2012;586(19):3263–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2012.06.048.

Cheng J, Huang J, Yuan S, Zhou S, Yan W, Shen W, Chen Y, Xia X, Luo A, Zhu D, et al. Circular RNA expression profiling of human granulosa cells during maternal aging reveals novel transcripts associated with assisted reproductive technology outcomes. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0177888. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177888.

Kulcheski FR, Christoff AP, Margis R. Circular RNAs are miRNA sponges and can be used as a new class of biomarker. J Biotechnol. 2016;238:42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.09.011.

Tang YY, Zhao P, Zou TN, Duan JJ, Zhi R, Yang SY, Yang DC, Wang XL. Circular RNA hsa_circ_0001982 promotes breast Cancer cell carcinogenesis through decreasing miR-143. DNA Cell Biol. 2017;36(11):901–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/dna.2017.3862.

Capel B, Swain A, Nicolis S, Hacker A, Walter M, Koopman P, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R. Circular transcripts of the testis-determining gene Sry in adult mouse testis. Cell. 1993;73(5):1019–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(93)90279-y.

Wang Y, Wang Z. Efficient backsplicing produces translatable circular mRNAs. Rna. 2015;21(2):172–9. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.048272.114.

Chen CY, Sarnow P. Initiation of protein synthesis by the eukaryotic translational apparatus on circular RNA s. Science (New York). 1995;268(5209):415–7. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7536344.

Jamnongjit M, Hammes SR. Ovarian steroids: the good, the bad, and the signals that raise them. Cell Cycle (Georgetown). 2006;5(11):1178–83. https://doi.org/10.4161/cc.5.11.2803.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the contributors of this study. And we thank LetPub (www.letpub.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC; 31460586 and 31960645).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TH conceived and designed the experiments; MXL analyzed and interpreted the data; YSC created the experimental images; LPM and YL collected the ovarian follicles samples; SX, XMS, YSS, and RNG participated in the RNA extraction and RT-PCR analysis; and SX wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Su Xie and Mengxun Li contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures involving animals were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Shihezi University. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards established in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and subsequent amendments.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, S., Li, M., Chen, Y. et al. Identification of circular RNAs in the ovarian follicles of Meishan and Duroc sows during the follicular phase. J Ovarian Res 13, 104 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-020-00709-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-020-00709-5