Abstract

Background

The telemedicine clinic for follow up after minor surgical procedures in general surgery is now ubiquitously considered a standard of care. However, this method of consultation is not the mainstay for preoperative assessment and counselling of patients for common surgical procedures such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The aim of this study was to evaluate the safety of assessing and counselling patients in the telemedicine clinic without a physical encounter for laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patients who were booked for laparoscopic cholecystectomy for benign gallbladder disease via general surgery telemedicine clinics from March 2020 to November 2021. The primary outcome was the cancellation rate on the day of surgery. The secondary outcomes were complication and readmission rates, with Clavein-Dindo grade III or greater deemed clinically significant. We performed a subgroup analysis on the cases cancelled on the day of surgery in an attempt to identify key reasons for cancellation following virtual clinic assessment.

Results

We identified 206 cases booked for laparoscopic cholecystectomy from telemedicine clinics. 7% of patients had a cancellation on the day of surgery. Only one such cancellation was deemed avoidable as it may have been prevented by a face-to-face assessment. Severe postoperative adverse events (equal to or greater than Clavien-Dindo grade III) were observed in 1% of patients, and required re-intervention. 30-day readmission rate was 11%.

Conclusions

Our series showed that it is safe and feasible to assess and counsel patients for laparoscopic cholecystectomy remotely with a minimal cancellation rate on the day of operation. Further work is needed to understand the effect of remote consultations on patient satisfaction, its environmental impact, and possible benefits to healthcare economics to support its routine use in general surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the entirety of the National Health System (NHS) was forced to reduce patient contact, impacting the way in which healthcare was provided[1] [2]. One of the major adaptations in outpatient hospital services and general practice settings was the use of telemedicine clinics[3]. The telemedicine clinic in general surgery has become widespread since the pandemic onset and has remained so following relaxation of restrictions on conventional in-person appointments. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine clinics had been commenced as a seemingly safe way to follow up patients after elective surgical procedures [4] [5] [6] [7]. During the pandemic, general surgery telemedicine clinics were used in part to assess and diagnose patients and consider their suitability for various invasive procedures[8, 9]. Furthermore, these virtual clinics were useful to plan and counsel patients for operations.

Telemedicine clinics throughout the pandemic allowed all patients and particularly those who were vulnerable, to be assessed without putting them at increased risk of contracting COVID-19. Post-pandemic, telemedicine clinic appears to be more accessible than a face-to-face appointment for patients given the busy demands of modern life; they can more easily be taken whilst, for example, at work. This may allow patients who previously may have delayed receiving medical attention to access it more easily. They are also beneficial to healthcare providers as they do not require outpatient facilities which saves cost[10] and allows more patients to be reviewed per clinic which decreases waiting times. Usage of telemedicine clinics is also more environmentally friendly, as they reduce carbon footprint, hospital footfall, and FFP2 mask usage[11] [12] [13].

An In-person clinical examination is traditionally viewed as a crucial component of patient evaluation and treatment planning in surgical practice. Hence, a major concern related to telemedicine clinics is that patients could not be adequately assessed and counselled for the need of an operation as well as their risks of having an invasive procedure. The inability to examine a patient may result in missed crucial information or important clinical factors which could adversely affect patient outcomes. Communication over the telephone may also be poorer between clinician and patient when compared with face-to-face appointments where non-verbal communicative cues may give the clinician important insights into the patients’ understanding and opinions. Despite these concerns, there have been reports of satisfactory telemedicine clinic outcomes for patients and providers in surgical specialities[14] [15] [16] [17] including even paediatric surgery [18]. Utilisation of telemedicine clinics has been shown to improve the outcomes of treatment in conditions such as vascular leg ulcers[19].

One study analysed large-scale trends of telemedicine conversion during the pandemic for surgical visits, and although this study found an increase in telemedicine utilisation, the overall uptake rate of telemedicine visits remained low, suggesting unidentified barriers to widespread telemedicine adoption in surgical care [20].

There is a concern that it is unsafe to assess patients for surgical intervention virtually, which in theory could result in increased complication rates due to inadequate assessment and underestimation of risks although it hasn’t been studied previously. Although the concept of virtual postoperative follow up in surgery has been widely adopted [21, 22], preoperative telemedicine assessment even for common invasive procedures hasn’t been unanimously accepted. The utilisation of such clinics for preoperative assessment of patients for the commonest surgical procedures if done safely could potentially have a massive impact on healthcare practice and economics[10]. It was shown that remote consultations were beneficial for liver transplant patients in terms of saving time and money, being less burdensome, and causing fewer negative impacts on patients’ health[23].

This study aims to assess whether telemedicine can be routinely used for the preoperative assessment of patients undergoing common general surgery procedures, in particular laparoscopic cholecystectomy as one the commonest operations performed in general surgery[24]. Our primary outcome of interest was the proportion of patients who experienced cancellation of surgery on the day of admission for laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Methods

Demographics

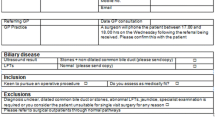

The study was conducted in a tertiary centre in the United Kingdom. We conducted a retrospective analysis of laparoscopic cholecystectomies booked via general surgery telemedicine clinics from 23 to 2020 to 30 November 2021. This covers the period between when a lockdown was imposed on United Kingdom residents and the move to ‘Plan B’ with the spread of the Omicron variant in December 2021. All patients aged 16 and older who were assessed, counselled and listed for laparoscopic cholecystectomy for benign gallbladder disease via general surgery telemedicine clinic were included for analysis. We define benign pathology of the gallbladder to include indications such as calculous cholecystitis, biliary colic, gallstone pancreatitis and gallbladder polyps. No malignant (gallbladder cancer) operations were included in our analysis and any patients with gallbladder cancer were excluded from our cohort. Cancellation, 30-day readmission and 30-day complication rates using the Clavein-Dindo classification system [25] were calculated. Clavein-Dindo grade III + complications were deemed clinically significant, and so these have been scrutinised further and presented in the results section below.

Telemedicine process

All patients were assessed on the phone in terms of their complaints and history of presenting complaints, past medical and surgical history, review of laboratory biochemistry and haematology, and scan results. The only aspect of assessment which wasn’t performed was physical examination due to the nature of virtual clinic. All patients were counselled on the phone and a standardised information leaflet was posted to all patients for completeness of the preoperative counselling process. All patients were also routinely assessed by a specialist nurse in our preoperative assessment clinic shortly prior to surgery. High-risk patients identified during the initial clinic assessment were routinely referred for anaesthetic assessment to pre-emptively identify and evaluate comorbidities which may impact fitness for surgery. The American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) physical status was generated from past medical history of the patient using medical notes [26].

Data analysis

Cancellations were further analysed on a per-patient basis to understand whether they could have been avoided through physical patient assessment.

Continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviation for normally distributed data and medians with range for non-normally distributed data as determined using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Statistical analysis was performed using JASP Version 0.16.2.

Results

Overall, we identified 240 patients who were assessed and booked for surgery after assessment in a telemedicine clinic. 206 required laparoscopic cholecystectomy for benign gallbladder disease and therefore were included into the final analysis. Of all 240 reviewed cases assessed and booked for surgery from telemedicine clinic, 187 (78%) patients had gallstones, 19 (8%) gallbladder polyps, 13 (5.4%) secondary liver tumour (colorectal metastases), 5 (2%) benign liver cyst, 5 (2%) primary pancreatic tumour, 4 (1.7%) primary liver tumour, 1 (0.4%) gallbladder tumour and 6 (2.5%) other pathologies. Of these, only benign gallbladder disease patients were included (gallstones and polyps). The baseline characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1.

There were 14 (7.0%) cancellations on the day of the surgery which are summarized in Table 2. 13 cancellations were unavoidable (Table 2) and only one of them was deemed potentially avoidable as the patient was not suitable for a day case procedure due to previous bariatric surgery and high BMI. This cancellation could have been avoided had the patient been assessed face-to-face manner.

21 patients (11%) of those who had surgery were readmitted within 30 days after discharge. The causes of readmissions are summarised in Table 3. Most of the readmitted patients didn’t require re-intervention and were managed conservatively either with extra analgesia, antiemetics or antibiotics. One patient (0.5%) was readmitted with an infected collection in the gallbladder bed, requiring laparoscopic drainage and wash out of this collection (a Clavien-Dindo IIIb complication). One patient (0.5%) was readmitted with a surgical site infection at the umbilical incision and required incision and drainage under local anaesthetic (a Clavien-Dindo IIIa complication). Therefore, the 30-day reintervention rate in our cohort of patients was 1%.

The American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) physical status was generated from past medical history of the patient using medical notes [26]. In our cohort majority of the patients were ASA 1–2 and only 12.1% were classified as ASA 3 (Table 1).

Overall, cancellation rate on the day of the surgery was low (7.0%) with only one cancellation (1/206 = 0.5%) deemed due to inadequate virtual assessment of the patient. 30-day readmission rate of the entire study population was 11% and significant complication rate (Clavien-Dindo 3a and above) was 1%.

Discussion

Benign gallbladder disease is a major global health burden. It is estimated that up to 15% of western population develops gallstones with 4% per year becoming symptomatic [28]. Thus, patients with benign gallbladder disease take up a large proportion of outpatient general and benign hepatobiliary outpatient clinics. The feasibility and safety of exclusively virtual assessment and counselling of patients who undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy have not been widely studied.

The analysis of the outcomes of the patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy booked and assessed from telemedicine clinic from this study showed that it is feasible and safe to continue its utilisation alongside conventional face-to-face appointments for selected patients. Cancellation, complication and 30-day readmission rates were used as surrogate endpoints of telemedicine clinic safety and feasibility. There were 14 (7.0%) operations cancelled on the day of the surgery, however only one (0.5%) was deemed to be related to inadequate telephone assessment of the patient and therefore potentially avoidable. Crudely, this is a similar proportion when compared with elective day case cancellation rates seen in larger studies published elsewhere [29]. The complication and readmission rates in our cohort of patients is comparable to national rates [30] [31] [32].

Due to consistent overbooking and relatively long waiting times, the desire is to continue telemedicine clinics at least for follow-up patients and newly referred low-risk patients, which could decrease the waiting time for appointments and improve patients’ access to healthcare professionals[33]. Telemedicine clinic may also be advantageous for the patients who are spared the cost and inconvenience of commute[34]. Another potential advantage of virtual clinics is reduced no-show rates which would positively impact on efficient utilisation of outpatient clinics[35]. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, all patients at our institution, including high risk cases with malignant pathologies were assessed virtually without physical presentation to the clinic. Following the easing of restrictions imposed during the pandemic and restoration of conventional physical appointments, telemedicine clinics were exclusively reserved for newly referred patients with benign gallbladder disease and low risk follow up patients.

The concept of telemedicine clinics was introduced long prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic [36, 37]. The obvious benefit to the healthcare provider is a reduction in clinic footfall, with more consultation rooms freed up for other essential clinical contact. Furthermore, the environmental benefit should not be overlooked[38]. In a world where every industry and sector are obligated to consider its carbon footprint, this added bonus is yet to be quantified and may represent future avenues of research. Expectedly, there has been increasing number of reports on the outcomes of telemedicine clinics in surgical practice since the onset of the pandemic.

In a prospective cohort study carried out from September 2021 to March 2022, authors assessed patients’ satisfaction with the telemedicine consultations [39]. Authors concluded that telemedicine assessment is associated with high levels of patient satisfaction regardless of patient age or gender. A small proportion of patients reported that they would prefer an in-person appointment compared to a telemedicine one. However, there is also contrary evidence to suggest that patients would prefer telemedicine follow-up versus in-person, especially for laparoscopic surgery [40]. Further systematic review of randomized controlled trials comparing telemedicine to conventional follow up in general surgery reported similar patient’s satisfaction level to standard care [41].

There have been few randomized controlled trials comparing outcomes of telemedicine and conventional face-to-face follow up appointments for postoperative general surgery patients [36] [4]. Both trials recruited patients for telemedicine postoperative follow up prior to the pandemic onset and included patients undergoing standard routine surgical procedures such as appendicectomy, cholecystectomy and abdominal wall hernia repair. Those studies concluded that telemedicine clinics are a safe and feasible alternative to standard face-to-face follow up for selected patients. Randomized controlled trials have also shown virtual consultations to be safe and effective and to reduce patient-borne costs when measured in a range of surgical and medical specialities including plastic surgery[42], orthopaedic surgery[43] [44] [45] [46], urology [47], chronic kidney disease [48], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [49] [50], mental health conditions [51] [52], chronic pain [53] [54] [55], adult and teenage diabetes [56] [57] [58].

One study from Mayo clinic assessed video telemedicine clinic in both surgical and non-surgical specialties in terms of concordance of provisional diagnoses established over such clinic visits compared against a reference standard diagnosis which yielded a high degree of diagnostic concordance compared with in person visits for most new clinical concerns[59].

One of the largest retrospective cohort studies assessing telemedicine uptake in surgical practice included 34,875 surgical referrals[60]. The aim of that study was to assess patient and provider characteristics associated with telemedicine uptake including variables such as surgical acuity (benign, urgent, and cancer) and surgical subspecialty, and to determine the predictors for and barriers to telemedicine usage. The benign diagnoses had the largest increase of telemedicine encounters, followed by cancer diagnoses and urgent diagnoses. Authors concluded that surgical specialties were able to shift to telemedicine promptly, safely, and efficiently in the preoperative and postoperative encounters of benign, urgent, and cancer diagnosis during COVID-19 related restrictions.

The main limitations of our study are its retrospective nature, the lack of a control group which would include patients assessed in face-to- face manner, relatively small sample size, no data regarding patients’ and clinicians’ satisfaction. We aimed to review all the cases booked from general surgery telemedicine clinic and operated within the timeframe of the study to ascertain there is no excessive cancellation, complication and readmission rates. The majority of the cases constituted patients with benign gallbladder disease who required day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

This study shows that it is feasible and safe to continue utilisation of telemedicine clinics for newly referred patients for certain surgical intervention. We intend to continue utilisation of telemedicine clinic for patients with benign gallbladder pathology which would potentially reduce waiting times and could be more flexible for medical staff and patients. The other advantages for patients would be reduced cost of travel, increased convenience, potentially reduced waiting time for intervention and therefore decreased occurrence of complications whilst waiting for surgery, no need for fixed office space. We advocate to have a low threshold to convert telemedicine clinic into face to face in case there is a doubt about its safety for individual patients or at patient’s request. More work is needed to determine whether or not virtual preoperative assessment is preferential from the patient’s perspective, as well as the fiscal implications of utilising remote consults as more routine practice.

Data Availability

On request from corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- NHS:

-

National health service

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anaesthesiologists

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

References

Willan J, King AJ, Jeffery K, Bienz N. Challenges for NHS hospitals during covid-19 epidemic. BMJ. 2020 Mar;20:368:m1117.

Al-Jabir A, Kerwan A, Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Khan M, Sohrabi C, et al. Impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on surgical practice - part 2 (surgical prioritisation). Int J Surg Lond Engl. 2020 Jul;79:233–48.

Gilbert AW, Billany JCT, Adam R, Martin L, Tobin R, Bagdai S, et al. Rapid implementation of virtual clinics due to COVID-19: report and early evaluation of a quality improvement initiative. BMJ Open Qual. 2020 May;9(2):e000985.

Fink T, Chen Q, Chong L, Hii MW, Knowles B. Telemedicine versus face-to-face follow up in general surgery: a randomized controlled trial. ANZ J Surg. 2022 Sep 7.

Carlock TC, Barrett JR, Kalvelage JP, Young JB, Nunez JM, Colonna AL, et al. Telephone follow-up for emergency general surgery procedures: Safety and Implication for Health Resource Use. J Am Coll Surg. 2020 Feb;230(2):228–36.

Greenhalgh T, Shaw S, Wherton J, Vijayaraghavan S, Morris J, Bhattacharya S, et al. Real-world implementation of video outpatient consultations at Macro, Meso, and Micro levels: mixed-method study. J Med Internet Res. 2018 Apr;17(4):e150.

Williams AM, Bhatti UF, Alam HB, Nikolian VC. The role of telemedicine in postoperative care. mHealth. 2018;4:11.

McMaster T, Wright T, Mori K, Stelmach W, To H. Current and future use of telemedicine in surgical clinics during and beyond COVID-19: A narrative review. Ann Med Surg 2012. 2021 Jun;66:102378.

Iqbal E, Bray JO, Sutton T, Akhter M, Orenstein SB, Nikolian VC. Perioperative Telemedicine utilization among geriatric patients being evaluated for Abdominal Wall Reconstruction and Hernia Repair. Telemed J E-Health Off J Am Telemed Assoc. 2022 Oct 17.

Demaerschalk BM, Cassivi SD, Blegen RN, Borah B, Moriarty J, Gullerud R, et al. Health Economic Analysis of Postoperative Video Telemedicine visits to patients’ Homes. Telemed J E-Health Off J Am Telemed Assoc. 2021 Jun;27(6):635–40.

Luo Y, Yu M, Wu X, Ding X, Wang L. Carbon footprint assessment of face masks in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: based on different protective performance and applicable scenarios. J Clean Prod. 2023 Feb;10:387:135854.

Du H, Huang S, Wang J. Environmental risks of polymer materials from disposable face masks linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Total Environ. 2022 Apr 1;815:152980.

Oliveira AM, Patrício Silva AL, Soares AMVM, Barceló D, Duarte AC, Rocha-Santos T. Current knowledge on the presence, biodegradation, and toxicity of discarded face masks in the environment. J Environ Chem Eng. 2023 Apr;11(2):109308.

Asiri A, AlBishi S, AlMadani W, ElMetwally A, Househ M. The Use of Telemedicine in Surgical Care: a systematic review. Acta inform Medica AIM J soc Med inform Bosnia Herzeg Cas Drustva Za Med inform BiH. 2018 Oct;26(3):201–6.

Hwa K, Wren SM. Telehealth follow-up in lieu of postoperative clinic visit for ambulatory surgery: results of a pilot program. JAMA Surg. 2013 Sep;148(9):823–7.

Kummerow Broman K, Roumie CL, Stewart MK, Castellanos JA, Tarpley JL, Dittus RS, et al. Implementation of a telephone postoperative clinic in an Integrated Health System. J Am Coll Surg. 2016 Oct;223(4):644–51.

Gunter RL, Chouinard S, Fernandes-Taylor S, Wiseman JT, Clarkson S, Bennett K, et al. Current use of Telemedicine for Post-Discharge Surgical Care: a systematic review. J Am Coll Surg. 2016 May;222(5):915–27.

Metzger GA, Cooper J, Lutz C, Jatana KR, Nishimura L, Deans KJ, et al. The value of telemedicine for the pediatric surgery patient in the time of COVID-19 and beyond. J Pediatr Surg. 2021 Aug;56(8):1305–11.

Bolton L. Telemedicine improves chronic Ulcer Outcomes. Wounds Compend Clin Res Pract. 2019 Apr;31(4):114–6.

Chao GF, Li KY, Zhu Z, McCullough J, Thompson M, Claflin J, et al. Use of Telehealth by Surgical Specialties during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Surg. 2021 Jul;1(7):620–6.

Uppal A, Kothari AN, Scally CP, Roland CL, Bednarski BK, Katz MHG, et al. Adoption of Telemedicine for Postoperative Follow-Up after Inpatient Cancer-Related surgery. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022 Jul;18(7):e1091–9.

Nikolian VC, Williams AM, Jacobs BN, Kemp MT, Wilson JK, Mulholland MW, et al. Pilot study to evaluate the safety, feasibility, and Financial Implications of a postoperative Telemedicine Program. Ann Surg. 2018 Oct;268(4):700–7.

Damery S, Jones J, O’Connell Francischetto E, Jolly K, Lilford R, Ferguson J. Remote consultations Versus Standard Face-to-face appointments for liver transplant patients in Routine Hospital Care: Feasibility Randomized Controlled Trial of myVideoClinic. J Med Internet Res. 2021 Sep;17(9):e19232.

Decker MR, Dodgion CM, Kwok AC, Hu YY, Havlena JA, Jiang W, et al. Specialization and the current practices of general surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2014 Jan;218(1):8–15.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004 Aug;240(2):205–13.

Dripps R. New classification of physical status. Anesthesiology. 1963;24:111.

Hartle A, McCormack T, Carlisle J, Anderson S, Pichel A, Beckett N, et al. The measurement of adult blood pressure and management of hypertension before elective surgery: Joint Guidelines from the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland and the british Hypertension Society. Anaesthesia. 2016 Mar;71(3):326–37.

Gurusamy KS, Davidson BR, Gallstones. BMJ. 2014 Apr;22:348:g2669.

Sarang B, Bhandoria G, Patil P, Gadgil A, Bains L, Khajanchi M, et al. Assessing the rates and reasons of Elective Surgical Cancellations on the day of surgery: a Multicentre Study from Urban Indian Hospitals. World J Surg. 2022 Feb;46(2):382–90.

CholeS Study Group, West Midlands Research Collaborative. Population-based cohort study of outcomes following cholecystectomy for benign gallbladder diseases. Br J Surg. 2016 Nov;103(12):1704–15.

CholeS Study Group, West Midlands Research Collaborative. Population-based cohort study of variation in the use of emergency cholecystectomy for benign gallbladder diseases. Br J Surg. 2016 Nov;103(12):1716–26.

Agabiti N, Stafoggia M, Davoli M, Fusco D, Barone AP, Perucci CA. Thirty-day complications after laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy: a population-based cohort study in Italy. BMJ Open. 2013;3(2):e001943.

Pabinger C, Lothaller H, Lorenz A, Dammerer D. Telemedicine versus on-site treatment at a surgical university clinic: study of 225 consecutive patients. Int J Med Inf. 2021 Jul;151:104460.

Hossain M, Dean EB, Kaliski D. Using Administrative Data to examine telemedicine usage among Medicaid beneficiaries during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. Med Care. 2022 Jul;1(7):488–95.

Alishahi ML, Sevick C, Mathieu S, Everhart R, Gritz M. No-Show rates for Telemedicine Versus In-Person appointments during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for Medicaid populations. J Ambul Care Manage. 2022 Dec;45(1):332–40.

Cremades M, Ferret G, Parés D, Navinés J, Espin F, Pardo F, et al. Telemedicine to follow patients in a general surgery department. A randomized controlled trial. Am J Surg. 2020 Jun;219(6):882–7.

Greenhalgh T, Vijayaraghavan S, Wherton J, Shaw S, Byrne E, Campbell-Richards D et al. Virtual online consultations: advantages and limitations (VOCAL) study. BMJ Open 2016 Jan 29;6(1):e009388.

Ravindrane R, Patel J. The environmental impacts of telemedicine in place of face-to-face patient care: a systematic review. Future Healthc J. 2022 Mar;9(1):28–33.

Ainger E, McCANCE A, Burford C, Black R, Fernandes R. Patient satisfaction with general surgery telephone consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic: a single surgeon experience. Minerva Surg. 2022 May 16.

Irarrázaval MJ, Inzunza M, Muñoz R, Quezada N, Brañes A, Gabrielli M, et al. Telemedicine for postoperative follow-up, virtual surgical clinics during COVID-19 pandemic. Surg Endosc. 2021 Nov;35(11):6300–6.

Blount E, Davey MG, Joyce WP. Patient reported satisfaction levels with the use of telemedicine for general surgery-A systematic review of randomized control trials. Surg Pract Sci. 2023 Mar;12:100152.

Westra I, Niessen FB. Implementing Real-Time Video Consultation in Plastic surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2015 Oct;39(5):783–90.

Sharareh B, Schwarzkopf R. Effectiveness of telemedical applications in postoperative follow-up after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014 May;29(5):918–922e1.

Marsh J, Hoch JS, Bryant D, MacDonald SJ, Naudie D, McCalden R, et al. Economic evaluation of web-based compared with in-person follow-up after total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014 Nov;19(22):1910–6.

Buvik A, Bugge E, Knutsen G, Småbrekke A, Wilsgaard T. Quality of care for remote orthopaedic consultations using telemedicine: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res 2016 Sep 8;16:483.

Marsh JD, Bryant DM, MacDonald SJ, Naudie DDR, McCalden RW, Howard JL, et al. Feasibility, effectiveness and costs associated with a web-based follow-up assessment following total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014 Sep;29(9):1723–8.

Viers BR, Lightner DJ, Rivera ME, Tollefson MK, Boorjian SA, Karnes RJ, et al. Efficiency, satisfaction, and costs for remote video visits following radical prostatectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Urol. 2015 Oct;68(4):729–35.

Katz IJ, Pirabhahar S, Williamson P, Raghunath V, Brennan F, O’Sullivan A, et al. iConnect CKD - virtual medical consulting: a web-based chronic kidney disease, hypertension and diabetes integrated care program. Nephrol Carlton Vic. 2018 Jul;23(7):646–52.

Nield M, Hoo GWS. Real-time telehealth for COPD self-management using Skype™. COPD. 2012 Dec;9(6):611–9.

Mark DD, Ikehara C, Matsuura C, Hara K, Li D. Validating the impact of Teaching Pursed-Lips Breathing with Skype: a pilot study. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2013 Dec;15(8):424–32.

Choi NG, Hegel MT, Marti N, Marinucci ML, Sirrianni L, Bruce ML. Telehealth problem-solving therapy for depressed low-income homebound older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry Off J Am Assoc Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014 Mar;22(3):263–71.

Chavooshi B, Mohammadkhani P, Dolatshahi B. A Randomized double-blind controlled trial comparing davanloo intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy as internet-delivered vs treatment as Usual for medically unexplained Pain: a 6-Month Pilot Study. Psychosomatics. 2016 Jun;57(3):292–300.

Bennell KL, Nelligan R, Dobson F, Rini C, Keefe F, Kasza J, et al. Effectiveness of an internet-delivered Exercise and Pain-Coping skills training intervention for persons with chronic knee Pain: a Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Apr;4(7):453–62.

Somers TJ, Kelleher SA, Westbrook KW, Kimmick GG, Shelby RA, Abernethy AP, et al. A small randomized controlled pilot trial comparing Mobile and Traditional Pain coping skills training protocols for Cancer Patients with Pain. Pain Res Treat. 2016;2016:2473629.

Müller KI, Alstadhaug KB, Bekkelund SI. Acceptability, feasibility, and cost of Telemedicine for Nonacute Headaches: a randomized study comparing video and traditional consultations. J Med Internet Res 2016 May 30;18(5):e140.

Freeman KA, Duke DC, Harris MA. Behavioral health care for adolescents with poorly controlled diabetes via Skype: does working alliance remain intact? J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013 May 1;7(3):727–35.

Hansen CR, Perrild H, Koefoed BG, Zander M. Video consultations as add-on to standard care among patients with type 2 diabetes not responding to standard regimens: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017 Jun;176(6):727–36.

Harris MA, Freeman KA, Duke DC. Seeing is believing: using Skype to Improve Diabetes Outcomes in Youth. Diabetes Care. 2015 Aug;38(8):1427–34.

Demaerschalk BM, Pines A, Butterfield R, Haglin JM, Haddad TC, Yiannias J et al. Assessment of Clinician Diagnostic Concordance With Video Telemedicine in the Integrated Multispecialty Practice at Mayo Clinic During the Beginning of COVID-19 Pandemic From March to June 2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2022 Sep 1;5(9):e2229958.

Kuehner G, Wu W, Choe G, Douaiher J, Reed M. Telemedicine implementation trends in surgical specialties before and after COVID-19 shelter in place: adjusting to a changing landscape. Surgery. 2022 Nov;172(5):1471–7.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TU, EK, SP, CC contributed to data collection, all authors contributed to study design, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript preparation, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Urbonas, T., Lakha, A.S., King, E. et al. The safety of telemedicine clinics as an alternative to in-person preoperative assessment for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with benign gallbladder disease: a retrospective cohort study. Patient Saf Surg 17, 23 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13037-023-00368-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13037-023-00368-7