Abstract

Background

Guidelines aim to support evidence-informed practice but are inconsistently used without implementation strategies. Our prior scoping review revealed that guideline implementation interventions were not selected and tailored based on processes known to enhance guideline uptake and impact. The purpose of this study was to update the prior scoping review.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, AMED, CINAHL, Scopus, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews for studies published from 2014 to January 2021 that evaluated guideline implementation interventions. We screened studies in triplicate and extracted data in duplicate. We reported study and intervention characteristics and studies that achieved impact with summary statistics.

Results

We included 118 studies that implemented guidelines on 16 clinical topics. With regard to implementation planning, 21% of studies referred to theories or frameworks, 50% pre-identified implementation barriers, and 36% engaged stakeholders in selecting or tailoring interventions. Studies that employed frameworks (n=25) most often used the theoretical domains framework (28%) or social cognitive theory (28%). Those that pre-identified barriers (n=59) most often consulted literature (60%). Those that engaged stakeholders (n=42) most often consulted healthcare professionals (79%). Common interventions included educating professionals about guidelines (44%) and information systems/technology (41%). Most studies employed multi-faceted interventions (75%). A total of 97 (82%) studies achieved impact (improvements in one or more reported outcomes) including 10 (40% of 25) studies that employed frameworks, 28 (47.45% of 59) studies that pre-identified barriers, 22 (52.38% of 42) studies that engaged stakeholders, and 21 (70% of 30) studies that employed single interventions.

Conclusions

Compared to our prior review, this review found that more studies used processes to select and tailor interventions, and a wider array of types of interventions across the Mazza taxonomy. Given that most studies achieved impact, this might reinforce the need for implementation planning. However, even studies that did not plan implementation achieved impact. Similarly, even single interventions achieved impact. Thus, a future systematic review based on this data is warranted to establish if the use of frameworks, barrier identification, stakeholder engagement, and multi-faceted interventions are associated with impact.

Trial registration

The protocol was registered with Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/4nxpr) and published in JBI Evidence Synthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Clinical practice guidelines include recommendations that are based on the best available evidence and are intended to optimize patient care [1, 2]. Given that guidelines support evidence-informed decision making and reduce practice variations, they are essential for planning, delivering, and improving high-quality health care [3]. However, policy and practice are not consistently informed by evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, which can lead to suboptimal care and inappropriate use of health care resources [4,5,6,7].

It is known that guideline implementation is a complex process that is often hindered by a variety of individual-, organisational-, and system-level barriers [8,9,10,11]. Common barriers identified across countries include, for example, limited knowledge of and negative attitudes toward existing guidelines, and lack of managers’ support for guideline implementation [12, 13].

Despite many barriers, guideline implementation is increasingly recognized as a process crucial to improving healthcare quality. Existing reviews have focused on specific clinical disciplines such as nursing and occupational therapy [14, 15], medical areas including cancer and venous thromboembolism prevention [16, 17], barriers of guideline implementation [18, 19], or specific topics such as the role of middle managers, nudge strategies, and de-implementation strategies [20,21,22].

Considerable knowledge is now available on how to optimize guideline implementation and uptake. Research shows that implementation interventions selected and tailored according to pre-identified barriers, theory, and/or stakeholder engagement can optimize guideline implementation and uptake [8, 23,24,25]. For example, a Cochrane review by Baker et al. of 26 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) revealed that tailoring interventions to overcome barriers was more likely to improve professional practice compared to no intervention or dissemination of guidelines [23]. Flottorp et al. employed rigorous methods to compile and establish consensus on a framework of 57 barriers of guideline implementation organized in 7 broad categories that implementers can use to help identify barriers [8]. Kim et al. first synthesized published research, then interviewed international guideline developers to compile strategies for integrating patient preferences in guidelines, an approach shown to improve relevance and uptake of recommendations [24]. Gagliardi et al. conducted a series of studies that identified and then elaborated on the concept of guideline implementability, referring to content included in or with guidelines such as implementation instructions or tools that can help users to implement recommendations [25]. Squires et al. conducted a meta-review of 25 reviews demonstrating that single interventions were as capable as multifaceted interventions of achieving positive impact [26]. To examine if and how guidelines were implemented based on these principles, the Guidelines International Network Implementation Working Group published a scoping review in 2015 on trends in guideline implementation [27]. The review included 32 studies published between 2004 and 2013. Most included studies employed educational meetings or materials targeted at patients and/or healthcare professionals rather than a range of implementation interventions selected and tailored according to pre-identified barriers, theory, and/or stakeholder engagement, approaches proven to optimize guideline implementation and uptake [8, 23,24,25]. The study also revealed inconsistent impact on patient and healthcare professional knowledge or behaviour, or clinical outcomes, possibly due to sub-optimal implementation. Moreover, the review included studies of guideline implementation in only four health topics (arthritis, diabetes, colorectal cancer, and heart failure), which resulted in few eligible studies and limited ability to identify trends in guideline implementation over time.

In the 8 years that have passed since literature searches were conducted for the 2015 scoping review, research continues to show that many patients do not access or experience guideline-recommended care. For example, 11 to 45% of American asthma specialists and primary care clinicians complied with asthma guidelines [28], 43 to 62% of 369,251 people from 20 countries achieved diabetes guideline targets [6], 44% of 30,113 Americans at high risk of hepatitis C virus received testing as per guidelines [29], and 36% of 414,851 Americans at 31 institutions did not receive recommended perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis [30]. Hence, further knowledge is needed to understand if guideline implementers are employing aforementioned strategies known to improve use of guidelines and realize associated benefits. The purpose of this study was to update and expand the 2015 scoping review [27]. The aim was to assess trends in guideline implementation, including the implementation strategies or interventions (hereafter, “interventions”) used, the implementation planning approaches employed for selecting and/or tailoring interventions, and the impact on patient or healthcare professional knowledge, behavior, or clinical outcomes.

The following research questions were investigated:

-

What approaches were used for implementation planning (i.e., pre-identified barriers, use of frameworks, or stakeholder engagement)?

-

What interventions have been used to implement guidelines in any healthcare context?

-

Do implementation planning approaches (pre-identify barriers, use of frameworks, stakeholder engagement) or multi-faceted interventions appear to lead to positive impact?

Methods

Approach

The scoping review methodological approach was guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s framework and the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis and is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) recommendations [31,32,33,34,35], see supplementary file 1 for the completed PRISMA-ScR checklist. A detailed protocol of this scoping review was published in JBI Evidence Synthesis [36]. The authors are members of the Guidelines International Network Implementation Working Group. The purpose of a scoping review is to explore what data is available on a certain topic, as well as whether there is sufficient data available for a more robust systematic review.

Eligibility criteria

Supplementary file 2 details inclusion and exclusion criteria. In brief, studies were eligible if they evaluated the impact of guideline implementation interventions. Guidelines were defined as documents intended to optimize patient care that include recommendations informed by the best available evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options [1, 2]. In case studies reported a local guideline, the research team investigated whether these clearly reflected and referenced (inter)national guidelines or were developed according to recognized methods, such as a literature review of the available evidence. Guidelines were considered for inclusion where they target patients aged 18 or older (and/or family or carers) or clinicians (physicians, nurses, allied health) of any specialty. Studies were eligible if they were conducted in primary or secondary/tertiary (hospital inpatient, outpatient, emergency) healthcare settings and published in English, French, or German (languages that could be translated by members of the research team). All authors contributed to development of the eligibility criteria, and two reviewers (AG and SP) further refined criteria based on review of the first 100 search results.

Search strategy

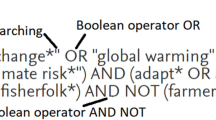

The search strategy (supplementary file 3) was based on that used for the 2015 scoping review [27] and was updated based on input from the research team and a medical librarian, in accordance with Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) criteria [37]. AG executed searches in MEDLINE, EMBASE, AMED (all Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Scopus, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Articles published from 2014 to January 2021 were included to capture relevant studies published subsequent to the execution of searches for the 2015 scoping review [27].

Study selection

One researcher (AG) uploaded search results into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) to remove duplicates. To prepare for screening, all screeners reviewed the 2015 publication [27], updated screening criteria, and an Excel file in which AG annotated screening decisions for the first 100 search results. Titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers (SP, SB, AR, JM, PG, ES, MC, ZM, or AG) against the eligibility criteria. Selected titles and abstracts were additionally screened by a third reviewer (AG or SP). Potentially relevant papers were retrieved and imported into Covidence. The full text of selected papers was assessed by two independent reviewers (AG and SP), who noted reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and analysis

Data was extracted from included papers by one researcher (SP, SB, AR, JM, PG, ES, MC, ZM, TK, EN, LPR, LK, or AG) and verified by a second researcher (KS). KS discussed any uncertainties or discrepancies with a third independent reviewer (AG or SP). The data extraction template, based on that used in the 2015 review [27] and a few additional items added by the research team, included study characteristics, guideline topic, study objective(s), implementation planning approaches for selecting implementation interventions (including the underpinning theories and frameworks, tailoring to pre-identified barriers, stakeholder engagement, or co-design processes), characteristics of the intervention (target group, single versus multi-faceted, type, content, format, delivery mode, timing, and involved personnel), and impact of interventions. Guideline topics were categorized according to the ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (ICD-11 MMS) version 02/2022 disease categories [38]. Theories and frameworks were grouped as per Nilsen’s literature review in Implementation Science [39]. Guideline implementation interventions were labeled according to the modified Mazza et al. taxonomy [40] that was expanded in the 2015 scoping review [27]. The taxonomy categorizes 51 interventions organized into five groups: professional, financial, organisational, structural changes, and regulatory [27, 41]. We extracted outcomes as reported by the authors to understand the impact of the intervention employed on each study, where the impact referred to improvements on patient or healthcare professional cognitive (e.g., beliefs, knowledge), behavioral (e.g., prescribing, self-management), or clinical (e.g., physiological measures) outcomes. As noted above in Approach, one purpose of a scoping review is to describe literature on a given topic, and in so doing, identify whether a future systematic review involving complex statistical analyses is feasible. Therefore, we described impact according to three broad categories: positive impact—studies that achieved improvements in all outcomes reported; mixed impact—studies that achieved improvements in some but not all outcomes reported; and no impact—studies that did not achieve improvement in any reported outcomes. Included studies were not appraised for methodological quality or risk of bias as this is not customary for scoping reviews. However, we indirectly addressed study quality by assessing and reporting research design, use of models, theories or frameworks, and thoroughness by which interventions were described.

Data analysis included developing summary statistics and frequency counts. KS developed summary tables and SP used this information to do descriptive statistics in IBM SPSS statistics (version 28.0.1.0). To identify possible associations between implementation planning and impact/outcomes that could be evaluated in a future systematic review, we counted the number of studies that did or did not achieve improvement in reported outcomes.

Results

Search results

The literature search resulted in 15,853 articles (Fig. 1). After removal of duplicates, 11,875 studies were not eligible and 384 were retrieved as potentially relevant. Of these, 208 articles were excluded by two additional reviewers because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Of the 176 full-text articles acquired and screened, 58 were excluded due to a variety of reasons described in the PRISMA flow diagram, such as the absence of a formal guideline and the impact of the intervention not evaluated. As a result, 118 studies were eligible for review. Details of all included studies are available in supplementary file 4, references [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159].

Characteristics of included studies

The highest number of studies were conducted in the USA (44, 37.3%), followed by the Netherlands (12, 10.2%), Australia (11, 9.3%), the UK (8, 6.8%), and Canada (7, 5.9%). With respect to research design, most studies involved an RCT (39, 33.1%), (cross-sectional) pre- and post-design (31, 26.3%) or a cohort study (18, 15.3%). Regarding study objectives, the majority of the eligible studies were undertaken to promote compliance with existing guidelines for quality improvement (106, 89.8%). Twelve studies (10.2%) implemented a newly developed or updated guideline. The guidelines in the included studies addressed the following 16 clinical topics: Diseases of the circulatory system (25, 21.2%); neoplasms (12, 10.2%); endocrine, nutritional, or metabolic diseases (12, 10.2%); mental, behavioral, or neurodevelopmental disorders (9, 7.6%); diseases of the respiratory system (8, 6.8%); injury, poisoning, or certain other consequences of external causes (7, 5.9%); factors influencing health status or contact with health services (7, 5.9%); certain infectious or parasitic diseases (6, 5.1%); diseases of the musculoskeletal system or connective tissue (6, 5.1%); diseases of the genitourinary system (4, 3.4%); diseases of the nervous system (3, 2.5%); diseases of the digestive system (3, 2.5%); external causes of morbidity or mortality (2, 1.7%); diseases of the skin (1, 0.8%); pregnancy, childbirth, or the puerperium (1, 0.8%); and symptoms, signs, or clinical findings, not elsewhere classified (12, 10.2%).

Implementation planning approaches

Table 1 summarizes the number of studies that selected or tailored implementation interventions based on pre-identified barriers, the use of frameworks and/or employed stakeholder engagement.

Theories and frameworks

Of the 118 eligible studies, 25 (21.2%) of those employed a least one theory or framework, as described by Nilsen [39]. Seven studies (28%) used a “process model,” which can help to understand all specific steps involved in the process of translating research into practice. Ten studies (40%) employed a “determinant framework,” which can help to explore all barriers and enablers that influence implementation outcomes. Fifteen studies (60%) utilised a “classic theory,” which is a theory that originates from fields external to implementation science, such as psychology, but can be applied to provide understanding of aspects of implementation. Seven studies (28%) used an “implementation theory,” that has been developed by implementation researchers to help explore explanations of certain implementation aspects. Only one study (4%) employed an “evaluation framework,” which focuses on the evaluation of implementation outcomes. Of the 11 distinct theories and frameworks, most frequently used were the theoretical domains framework TDF (7, 28% of 25), to identify implementation barriers and enablers [48, 68, 70, 74, 85, 105, 132], and social cognitive theories (7, 28%), to provide understanding and explanation of aspects of implementation [61, 62, 86, 93, 114, 135, 155]. Seven (28% of 25) studies used more than one theory or framework. Besides the theories and frameworks as categorized by Nilsen [39], the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle was used in 11 studies [42, 45, 51, 55, 65, 90, 94, 103, 114, 140, 143], the UK Medical Research Council framework for complex interventions [171] and a program logic model were both used in 1 study, respectively [93] and [118].

Pre-identified barriers and tailoring

Fifty-nine (50% of 118) studies identified one or more barriers. Most frequently, barriers were identified by the literature (33, 55.9% of 59), surveys (16, 27.1%), group discussions (11, 18.6%), and interviews (10, 16.9%). Twenty-three (39%) studies used more than one method to identify barriers. Seven (11.9%) studies identified barriers but did not specify how that was done. Of the 59 studies that pre-identified barriers, 38 (64.4% of 59) of those reported that they tailored their intervention to address the barriers. Of those, most did not report which method they used to map pre-identified barriers to implementation interventions, while 5 (13.2% of 38) studies referenced the Behaviour Change Wheel [170].

Stakeholder engagement

Stakeholder engagement was employed in 42 (35.6% of 118) studies. Most of the studies referred to co-designing components of their implementation interventions with professionals (33, 78.6% of 42). A smaller number of studies included engagement with patients (2, 4.8%) or with both professionals and patients (7, 16.7%). The majority of the stakeholder engagement sessions were based on group discussions (30, 71.4%). Ten studies (23.8%) did not specify the method that they used to engage stakeholders. In most studies, detailed information was lacking about the extent of stakeholder engagement and how the stakeholder engagement informed intervention selection or design. There were only 3 studies (7.1%) in which the intervention was entirely based on stakeholder engagement [84, 131, 150].

Various implementation planning approaches were used in complementary ways. Twelve of the included studies (10.2%) combined pre-identified barriers with tailoring of the intervention and stakeholder engagement [42, 45, 79, 89, 98, 106, 118, 119, 131, 141, 158]. Nine of the included studies (7.6%) employed a theory or framework, pre-identified barriers, and tailoring [48, 56, 62, 67, 68, 70, 86, 114, 134]. Eight studies entailed pre-identified barriers and stakeholder engagement [87, 97, 99, 125, 147, 148, 150, 153]. One study included a theory or framework, pre-identified barriers, and stakeholder engagement [93], while another study incorporated a framework and stakeholder engagement [94]. Nine of the included studies (7.6%) used all implementation planning approaches in their study [52, 58, 85, 103, 105, 132, 137, 151, 152].

Implementation interventions

Table 2 summarizes the implementation interventions used in included studies according to the modified Mazza et al. taxonomy [40]. The majority of the studies involved a multi-faceted (88, 74.6%) rather than a single (30, 25.4%) intervention. Multi-faceted interventions included a mean of 5 interventions (range 2 to 13). Overall, 40 of the 52 distinct interventions types were employed from the modified Mazza taxonomy of guideline implementation strategies. The most frequently used types of interventions were educating groups of professionals about guideline intent and benefits (52, 44.1%), information/communication technology (48, 40.7%), and providing feedback to professionals on compliance (40, 33.9%).

Impact on knowledge, behavior, and outcomes

The majority of studies (66, 55.9%) achieved positive impact, referring to improvements in all outcomes reported, and 31 (26.3%) studies achieved mixed impact, referring to improvement in some but not all outcomes reported. Overall, 97 (82.2%) studies achieved positive impact on one or more reported outcomes.

The most frequently reported impact was healthcare professionals’ behavior (e.g., medication prescribing) (60, 50.8%), see Table 3. Twenty-nine studies (24.6%) targeted both patient/family and healthcare professional related outcomes.

The interventions did not report any iatrogenic effects or unintended consequences. Two studies reported negative effects on one of their secondary outcome measures [68, 89].

Factors influencing impact

Implementation planning approaches and multi-faceted interventions do not appear to be possibly associated with positive impact (see Table 4), given that there is not a big difference in number of studies with overall positive impact versus mixed or no impact. Studied that used a theory or framework showed only slightly more frequently mixed or no change in study results (12.7%) in comparison to overall positive study impact (8.5%). The same can be said about pre-identified barriers, 26.3% of studies demonstrated mixed or no change, and 23.7% of studies had overall positive impact. The difference between overall positive study impact and mixed or no study impact is slightly bigger for tailoring intervention to pre-identified barriers (12.7 versus 19.5%). Stakeholder engagement revealed in about half of the studies overall positive impact (18.6 versus 16.9%). Single interventions seemed to lead more frequently to overall positive impact (17.8 versus 7.6%), while multi-faceted interventions revealed in about half of the studies overall positive impact (38.1 versus 36.4%).

Discussion

This review included 118 studies published from 2014 to January 2021 that were largely conducted in high-income countries to improve compliance with existing guidelines or related outcomes across 16 broad disease categories. With respect to implementation planning approaches, 21% studies employed one or more of 11 distinct theories or frameworks, 50% pre-identified barriers using one or more approaches, and 36% reported engaging patients and/or professionals in planning processes. With respect to implementation interventions, a total of 40 intervention types were employed from among the 52 included in the modified Mazza taxonomy of guideline implementation strategies [40], most commonly educating professionals about guidelines (44%), information systems or technology (41%), and informing professionals of their compliance (34%). The majority of studies employed multi-faceted interventions (75%) with a range of 2 to 13 interventions. With respect to impact, 82% of studies achieved improvements in one or more reported outcomes, most often on professional behavior. Beneficial outcomes seemed to be achieved regardless of whether implementation planning was employed, the intervention was single versus multi-faceted, or type of intervention used. However, possible associations are not clear and a future systematic review is needed to more definitively establish that area.

In comparison with the first version of this review published in 2015 [27], this updated review included many more studies across a greater number of disease categories (32 studies in 2015 versus 118 in this review). The studies included in this review more often employed one or more implementation planning approaches compared with 19% that did so in our 2015 review [27]. Similar to the 2015 review, most studies in this review employed multi-faceted strategies. However, unlike the 2015 review in which most studies used educational meetings or material, studies in this review employed a broad range of types of interventions, and information technology and audit & feedback were nearly as common as educational interventions. Similar to the original review, this review found that most studies achieved positive impact, and this was not associated with the use of implementation planning approaches, type of intervention, or multi-faceted approaches.

Previous reviews on guideline implementation identified common implementation interventions or strategies, which included dissemination, education and training, social interaction, decision support systems, and standing orders [172]. A review by Chan et al. specifically focused on the impact of four types of interventions directed at professionals: reminders, educational outreach visits, audit & feedback and incentives, revealing largely positive impact achieved by educational outreach and audit & feedback, and mixed results for reminders and incentives [173]. In contrast to these studies, our review included many more studies and explored the full range of interventions or strategies that have been targeted to patients and/or healthcare professionals. Another added value of our review is that we included a variety of disease categories, while other reviews focused on strategies used to implement guidelines on specific topics, such as nursing guidelines [14, 174]. Our review also included many more studies, namely 118, in comparison to other implementation-focused reviews, which included 41 to 69 studies [14, 172,173,174].

Spoon et al. found in their systematic review that 43% of studies used barrier assessment to select and tailor interventions [174], which is in line with the 50% of included studies in our review. A systematic review by Cassidy et al. found that most studies combined educational meetings with educational materials, but did not assess how interventions were chosen or factors that influenced impact [14]. In contrast to previously published reviews, our review identified other factors thought to influence impact such as implementation planning approaches and multi-faceted interventions.

A notable finding of this review is that, compared to our 2015 review, more efforts to promote the use of guidelines are informed by implementation planning approaches including the use of theory or frameworks, pre-identification of barriers, and stakeholder engagement in implementation planning. This concurs with another scoping review that focused specifically on use of theory in guideline implementation planning, of 175 included studies, 47% employed theory, and of those, 76% used theory to inform surveys or interviews that identified barriers of guideline use as a preliminary step in implementation planning [12]. This could be attributed to the original Cochrane review that revealed the importance of tailoring interventions [175] and a worldwide trend in engaging stakeholders in both research and quality improvement [176, 177]. This could also be attributed to decades of accumulated research on how to optimize guideline implementation, which has influenced the consciousness and practices of guideline implementers. Similarly, this review showed that the types of interventions employed have broadened beyond educational meetings and materials compared with our 2015 review. This is also likely a reflection of greater awareness of the need for implementation planning to select and tailor interventions that best match a given healthcare context [175], and knowledge of the fact that educational interventions generally have a small impact on professional behavior or outcomes [178]. Given that the vast majority of included studies achieved positive impact in one or more outcomes, this review reinforces the relevance and utility of these approaches for selecting and tailoring interventions, although publication bias could also be at play. Most implementation studies included in our review did not address the costs and economic impact of the interventions, which is an important consideration when informing policy planning decisions.

This review revealed, as have many other reviews [14, 27, 172,173,174], that most guideline implementers employed multi-faceted interventions. This continuing trend is remarkable because a 2014 meta-review by Squires et al. showed that single strategies were capable of achieving positive impact [26], as did our 2015 review [27] and this updated review. This belief may be perpetuated by reviews of studies that largely employed multi-faceted interventions, many of which achieved positive outcomes, and conclude that multi-faceted interventions are essential [179], and by the belief that interventions should address every barrier identified. However, outside of the context of funded research, most guideline developers possess few resources to implement guidelines, and the vast majority of guidelines are disseminated and not implemented, leading to low rates of compliance with guidelines, of which very few benefit from becoming the subject of implementation research. Thus, further research is needed to generate insight on how to prioritize barriers and corresponding interventions as a means of simplifying both implementation planning and implementation, ultimately making it easier and less costly for guideline implementers to promote uptake of their guidelines.

This review featured both strengths and limitations. With respect to strengths, we used rigorous scoping review methods including triplicate screening by international experts in guideline implementation and duplicate data extraction [31,32,33,34, 37] and complied with reporting standards for scoping reviews [180] and for search strategies [37]. By including guidelines on any clinical topic, we expanded the breadth of the findings beyond our original 2015 scoping review [27] and reviews of guideline implementation by others [172, 174]. We also included non-English language studies, those few were identified. With respect to limitations, as with most reviews, our search strategy may not have identified all relevant studies. Although we screened over 12,000 titles/abstracts, our eligibility criteria may have been overly stringent. Studies that achieved improvements in all reported study outcomes are not necessarily more meaningful than those studies that achieved improvements in only some, but not all, of the reported outcomes. We did not undertake complex statistical analyses to quantify study impact or identify determinants of the positive impact of interventions. However, this scoping review identified that sufficient literature is available to do so and we will undertake such analyses in a future systematic review. That systematic review will appraise the methodological quality of included studies, something not required of a scoping review. Additionally, given the lack of risk of bias assessment or a process to establish certainty in the synthesised results, the results of our analyses should be interpreted judiciously and be viewed as indicatory as opposed to confirmatory. The majority of studies were conducted in a few high-income countries so the findings may not be relevant to low- or middle-income countries.

Conclusion

This review of 118 studies found that more studies used processes to select and tailor interventions, and a wider array of types of interventions, in comparison to a similar review published in 2015. Given that most studies achieved impact, this might reinforce the need for implementation planning approaches, such as pre-identifying barriers, using theory or frameworks, tailoring interventions, and engaging stakeholders in co-design process. However, even studies that did not employ implementation planning approaches achieved impact. Similarly, both single versus multi-faceted interventions achieved impact. Thus, a future systematic review based on this data is warranted to establish if barrier identification, use of theory/frameworks, tailored interventions, stakeholder engagement, and multi-faceted interventions are associated with impact.

Availability of data and materials

All data is available in supplementary files.

Abbreviations

- PRISMA-ScR:

-

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Scoping Review

- ICD-11 MMS:

-

ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics

- TDF:

-

Theoretical domains framework

- PDSA:

-

Plan Do Study Act

References

Alonso-Coello P, Irfan A, Sola I, Gich I, Delgado-Noguera M, Rigau D, et al. The quality of clinical practice guidelines over the last two decades: a systematic review of guideline appraisal studies. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(6):e58.

Lenzer J, Hoffman JR, Furberg CD, Ioannidis JP. Guideline Panel Review Working G. Ensuring the integrity of clinical practice guidelines: a tool for protecting patients. BMJ. 2013;347:f5535.

Shekelle P, Woolf S, Grimshaw JM, Schunemann HJ, Eccles MP. Developing clinical practice guidelines: reviewing, reporting, and publishing guidelines; updating guidelines; and the emerging issues of enhancing guideline implementability and accounting for comorbid conditions in guideline development. Implement Sci. 2012;7:62.

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–45.

Runciman WB, Hunt TD, Hannaford NA, Hibbert PD, Westbrook JI, Coiera EW, et al. CareTrack: assessing the appropriateness of health care delivery in Australia. Med J Aust. 2012;197(2):100–5.

Khunti K, Ceriello A, Cos X, De Block C. Achievement of guideline targets for blood pressure, lipid, and glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;137:137–48.

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7:50.

Flottorp SA, Oxman AD, Krause J, Musila NR, Wensing M, Godycki-Cwirko M, et al. A checklist for identifying determinants of practice: a systematic review and synthesis of frameworks and taxonomies of factors that prevent or enable improvements in healthcare professional practice. Implement Sci. 2013;8:35.

Francke AL, Smit MC, de Veer AJ, Mistiaen P. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: a systematic meta-review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8:38.

Mickan S, Burls A, Glasziou P. Patterns of ‘leakage’ in the utilisation of clinical guidelines: a systematic review. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87(1032):670–9.

Gagliardi AR. “More bang for the buck”: exploring optimal approaches for guideline implementation through interviews with international developers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:404.

Liang L, Bernhardsson S, Vernooij RW, Armstrong MJ, Bussieres A, Brouwers MC, et al. Use of theory to plan or evaluate guideline implementation among physicians: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):26.

Kastner M, Bhattacharyya O, Hayden L, Makarski J, Estey E, Durocher L, et al. Guideline uptake is influenced by six implementability domains for creating and communicating guidelines: a realist review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(5):498–509.

Cassidy CE, Harrison MB, Godfrey C, Nincic V, Khan PA, Oakley P, et al. Use and effects of implementation strategies for practice guidelines in nursing: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2021;16(1):102.

Murrell JE, Pisegna JL, Juckett LA. Implementation strategies and outcomes for occupational therapy in adult stroke rehabilitation: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2021;16(1):105.

Tomasone JR, Kauffeldt KD, Chaudhary R, Brouwers MC. Effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies on health care professionals’ behaviour and patient outcomes in the cancer care context: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):41.

Abboud J, Abdel Rahman A, Kahale L, Dempster M, Adair P. Prevention of health care associated venous thromboembolism through implementing VTE prevention clinical practice guidelines in hospitalized medical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):49.

McArthur C, Bai Y, Hewston P, Giangregorio L, Straus S, Papaioannou A. Barriers and facilitators to implementing evidence-based guidelines in long-term care: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Implement Sci. 2021;16(1):70.

Bierbaum M, Rapport F, Arnolda G, Nic Giolla Easpaig B, Lamprell K, Hutchinson K, et al. Clinicians’ attitudes and perceived barriers and facilitators to cancer treatment clinical practice guideline adherence: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative literature. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):39.

Yoong SL, Hall A, Stacey F, Grady A, Sutherland R, Wyse R, et al. Nudge strategies to improve healthcare providers’ implementation of evidence-based guidelines, policies and practices: a systematic review of trials included within Cochrane systematic reviews. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):50.

Birken S, Clary A, Tabriz AA, Turner K, Meza R, Zizzi A, et al. Middle managers’ role in implementing evidence-based practices in healthcare: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):149.

Rietbergen T, Spoon D, Brunsveld-Reinders AH, Schoones JW, Huis A, Heinen M, et al. Effects of de-implementation strategies aimed at reducing low-value nursing procedures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):38.

Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, Shaw EJ, Cheater F, Flottorp S, et al. Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(3):CD005470.

Kim C, Berta W, Gagliardi A. Exploring approaches to identify, incorporate and report patient preferences in guidelines: qualitative interviews with guideline developers. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;104(4):703–8.

Gagliardi A, Brouwers M, Palda V, Lemieux-Charles L, Grimshaw J. How can we improve guideline use? A conceptual framework of implementability. Implement Sci. 2011;6:26.

Squires JE, Sullivan K, Eccles MP, Worswick J, Grimshaw JM. Are multifaceted interventions more effective than single-component interventions in changing health-care professionals’ behaviours? An overview of systematic reviews. Implement Sci. 2014;9:152.

Gagliardi AR, Alhabib S. members of Guidelines International Network Implementation Working G. Trends in guideline implementation: a scoping systematic review. Implement Sci. 2015;10:54.

Cloutier MM, Salo PM, Akinbami LJ, Cohn RD, Wilkerson JC, Diette GB, et al. Clinician agreement, self-efficacy, and adherence with the guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(3):886–94 e4.

Mkuu RS, Shenkman EA, Muller KE, Huo T, Salloum RG, Cabrera R, et al. Do patients at high risk for Hepatitis C receive recommended testing? A retrospective cohort study of statewide Medicaid claims linked with OneFlorida clinical data. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(50):e28316.

Bardia A, Treggiari MM, Michel G, Dai F, Tickoo M, Wai M, et al. Adherence to guidelines for the administration of intraoperative antibiotics in a nationwide US sample. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12):e2137296.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Baxter L, Tricco AC, Straus S, et al. Advancing scoping study methodology: a web-based survey and consultation of perceptions on terminology, definition and methodological steps. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:305.

Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Adelaide: JBI; 2020. [Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global]

Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2119–26.

Gagliardi AR, Malinowski J, Munn Z, Peters S, Senerth E. Trends in guideline implementation: an updated scoping review protocol. JBI Evid Synth. 2021;19(0):1–7

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel D, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6.

WHO. ICD-11: International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision World Health Organization; 2022 [10th of March 2022]. Available from: https://icd.who.int/en.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10:53.

Mazza D, Bairstow P, Buchan H, Chakraborty S, Van Hecke O, Grech C. Refining a taxonomy of guideline implementation. Implement Sci. 2013;8:32.

Schunemann H, Wiercioch W, Etxeandia I, Falavigna M, Santesso N, Mustafa R. Guidelines 2.0: systematic development of a comprehensive checklist for a successful guideline enterprise. Can Med Assoc J. 2014;186:123–42.

Fally M, Diernaes E, Israelsen S, Tarp B, Benfield T, Kolte L, et al. The impact of a stewardship program on antibiotic administration in community-acquired pneumonia: results from an observational before-after study. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:208–13.

Ingram A, Valente M, Dzurec MA. Evaluating pharmacist impact on guideline-directed medical therapy in patients with reduced ejection fraction heart failure. J Pharm Pract. 2021;34(2):239–46.

Akamike IC, Okedo-Alex IN, Uneke CJ, Uro-Chukwu HC, Chukwu OE, Ugwu NI, et al. Evaluation of the effect of an educational intervention on knowledge and adherence to HIV guidelines among frontline health workers in Alex-Ekwueme Federal University Teaching Hospital Abakaliki. Nigeria Afr Health Sci. 2020;20(3):1080–9.

Azizoddin DR, Lakin JR, Hauser J, Rynar LZ, Weldon C, Molokie R, et al. Meeting the guidelines: Implementing a distress screening intervention for veterans with cancer. Psychooncology. 2020;29(12):2067–74.

Azubuike UC, Cooper D, Aplin-Snider C. Using United States preventive services task force guidelines to improve a family medicine clinic’s lung cancer screening rates: a quality improvement project. J Nurse Pract. 2020;16(10):e169–e72.

Cassagnol M, Hai O, Sherali SA, D'Angelo K, Bass D, Zeltser R, et al. Impact of cardiologist intervention on guideline-directed use of statin therapy. World J Cardiol. 2020;12(8):419–26.

Ciprut SE, Kelly MD, Walter D, Hoffman R, Becker DJ, Loeb S, et al. A clinical reminder order check intervention to improve guideline-concordant imaging practices for men with prostate cancer: a pilot study. Urology. 2020;145:113–9.

Daud MH, Ramli AS, Abdul-Razak S, Haniff J, Tg Abu Bakar Sidik TMI, NKB MH, et al. Effectiveness of the EMPOWER-PAR intervention on primary care providers’ adherence to clinical practice guideline on the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. Open Access Macedonian. J Med Sci. 2020;8(B):470–9.

Gupta M, Maamoun W, Maher M, Jaffe W. Ensuring universal assessment and management of vitamin D status in melanoma patients at secondary care level: a service improvement project. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2020;81(10):1–5.

Holmes CE, Ades S, Gilchrist S, Douce D, Libby K, Rogala B, et al. Successful model for guideline implementation to prevent cancer-associated thrombosis: venous thromboembolism prevention in the ambulatory cancer clinic. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(9):e868–e74.

Levi CR, Attia JA, D'Este C, Ryan AE, Henskens F, Kerr E, et al. Cluster-randomized trial of thrombolysis implementation support in metropolitan and regional Australian stroke centers: lessons for individual and systems behavior change. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(3):e012732.

Lipscomb J, Escoffery C, Gillespie TW, Henley SJ, Smith RA, Chociemski T, et al. Improving screening uptake among breast cancer survivors and their first-degree relatives at elevated risk to breast cancer: results and implications of a randomized study in the state of Georgia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):977.

Marszalek D, Martinson A, Smith A, Marchand W, Sweeney C, Carney J, et al. Examining the effect of a whole health primary care pain education and opioid monitoring program on implementation of VA/DoD-recommended guidelines for long-term opioid therapy in a primary care chronic pain population. Pain Med. 2020;21(10):2146–53.

McGuinness R, Keevil H, Sharif A, Lau TK, Crookes W, Bhamm R, et al. Improving the percentage of HIV tests offered to patients admitted to an acute hospital trust with community-acquired pneumonia. BMJ Open. Qual. 2020;9(4):e001102.

Nguyen N, Nguyen T, Truong V, Dang K, Siman N, Shelley D. Impact of a tobacco cessation intervention on adherence to tobacco use treatment guidelines among village health workers in Vietnam. Glob Health Promot. 2020;27(3):24–33.

Roberts S, Busby E. Implementing clinical guidelines into practice: the osteoarthritis self-management and independent-living support (OASIS) group-A service evaluation. Musculoskeletal Care. 2020;18(3):404–11.

Rust C, Prior RM, Stec M. Implementation of a clinical practice guideline in a primary care setting for the prevention and management of obesity in adults. Nurs Forum. 2020;55(3):485–90.

Segala FV, Murri R, Taddei E, Giovannenze F, Del Vecchio P, Birocchi E, et al. Antibiotic appropriateness and adherence to local guidelines in perioperative prophylaxis: results from an antimicrobial stewardship intervention. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9(1):164.

Silverberg ND, Panenka WJ, Lizotte PP, Bayley MT, Dance D, Li LC. Promoting early treatment for mild traumatic brain injury in primary care with a guideline implementation tool: a pilot cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e035527.

Tramontt CR, Jaime PC. Improving knowledge, self-efficacy and collective efficacy regarding the Brazilian dietary guidelines in primary health care professionals: a community controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):214.

Trogrlic Z, van der Jagt M, van Achterberg T, Ponssen H, Schoonderbeek J, Schreiner F, et al. Prospective multicentre multifaceted before-after implementation study of ICU delirium guidelines: a process evaluation. BMJ Open. Qual. 2020;9(3):e000871.

Vani A, Kan K, Iturrate E, Levy-Lambert D, Smilowitz NR, Saxena A, et al. Leveraging clinical decision support tools to improve guideline-directed medical therapy in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease at hospital discharge. Cardiol J. 2020. https://doi.org/10.5603/CJ.a2020.0126

Wu SY, Lazar AA, Gubens MA, Blakely CM, Gottschalk AR, Jablons DM, et al. Evaluation of a national comprehensive cancer network guidelines-based decision support tool in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e209750.

Zgierska AE, Robinson JM, Lennon RP, Smith PD, Nisbet K, Ales MW, et al. Increasing system-wide implementation of opioid prescribing guidelines in primary care: findings from a non-randomized stepped-wedge quality improvement project. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):245.

Abbood SK, Assad HC, Al-Jumaili AA. Pharmacist intervention to enhance postoperative fluid prescribing practice in an Iraqi hospital through implementation of NICE guideline. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2019;17(3):1552.

Bernhardsson S, Larsson MEH. Does a tailored guideline implementation strategy have an impact on clinical physiotherapy practice? A nonrandomized controlled study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2019;25(4):575–84.

Bosch M, McKenzie JE, Ponsford JL, Turner S, Chau M, Tavender EJ, et al. Evaluation of a targeted, theory-informed implementation intervention designed to increase uptake of emergency management recommendations regarding adult patients with mild traumatic brain injury: results of the NET cluster randomised trial. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):4.

Chen AKD, Duffy EJ, Ritchie SR, Thomas MG. Diagnostic accuracy and adherence to treatment guidelines in adult inpatients with urinary tract infections in a tertiary hospital. J Pharm Pract Res. 2019;49(3):246–53.

Dhopte P, French SD, Quon JA, Owens H, Bussieres A. Canadian Chiropractic Guideline I. Guideline implementation in the Canadian chiropractic setting: a pilot cluster randomized controlled trial and parallel study. Chiropr Man Therap. 2019;27:31.

Dreijer AR, Diepstraten J, Leebeek FWG, Kruip M, van den Bemt P. The effect of hospital-based antithrombotic stewardship on adherence to anticoagulant guidelines. Int J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;41(3):691–9.

Gulayin PE, Lozada A, Beratarrechea A, Gutierrez L, Poggio R, Chaparro RM, et al. An educational intervention to improve statin use: cluster RCT at the primary care level in Argentina. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(1):95–105.

Huang KTL, Blazey-Martin D, Chandler D, Wurcel A, Gillis J, Tishler J. A multicomponent intervention to improve adherence to opioid prescribing and monitoring guidelines in primary care. J Opioid Manag. 2019;15(6):445–53.

Jolliffe L, Morarty J, Hoffmann T, Crotty M, Hunter P, Cameron ID, et al. Using audit and feedback to increase clinician adherence to clinical practice guidelines in brain injury rehabilitation: A before and after study. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213525.

Lee CK, Lai CL, Lee MH, Su FY, Yeh TS, Cheng LY, et al. Reinforcement of patient education improved physicians’ adherence to guideline-recommended medical therapy after acute coronary syndrome. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0217444.

Marcial E, Graves BA. Implementation and evaluation of diabetes clinical practice guidelines in a primary care clinic serving a hispanic community. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2019;16(2):9.

McAdam-Marx C, Tak C, Petigara T, Jones NW, Yoo M, Briley MS, et al. Impact of a guideline-based best practice alert on pneumococcal vaccination rates in adults in a primary care setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):474.

Moseng T, Dagfinrud H, Osteras N. Implementing international osteoarthritis guidelines in primary care: uptake and fidelity among health professionals and patients. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27(8):1138–47.

Orchard J, Neubeck L, Freedman B, Li J, Webster R, Zwar N, et al. eHealth tools to provide structured assistance for atrial fibrillation screening, management, and guideline-recommended therapy in metropolitan general practice: the AF - SMART study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(1):e010959.

O'Sullivan CT, Rogers WK, Ackman M, Goto M, Hoff BM. Implementation of a multifaceted program to sustainably improve appropriate intraoperative antibiotic redosing. Am J Infect Control. 2019;47(1):74–7.

Takaesu Y, Watanabe K, Numata S, Iwata M, Kudo N, Oishi S, et al. Improvement of psychiatrists’ clinical knowledge of the treatment guidelines for schizophrenia and major depressive disorders using the ‘Effectiveness of Guidelines for Dissemination and Education in Psychiatric Treatment (EGUIDE)’ project: A nationwide dissemination, education, and evaluation study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;73:7.

Wilkins B, Hullikunte S, Simmonds M, Sasse A, Larsen P, Harding SA. Improving the prescribing gap for guideline recommended medications post myocardial infarction. Heart Lung Circ. 2019;28(2):257–62.

Carter BL, Levy B, Gryzlak B, Xu Y, Chrischilles E, Dawson J, et al. Cluster-randomized trial to evaluate a centralized clinical pharmacy service in private family medicine offices. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(6):e004188.

Dodek P, McKeown S, Young E, Dhingra V. Development of a provincial initiative to improve glucose control in critically ill patients. International J Qual Health Care. 2019;31(1):49–56.

Dziedzic KS, Healey EL, Porcheret M, Afolabi EK, Lewis M, Morden A, et al. Implementing core NICE guidelines for osteoarthritis in primary care with a model consultation (MOSAICS): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2018;26(1):43–53.

Etxeberria A, Alcorta I, Perez I, Emparanza JI, Ruiz de Velasco E, Iglesias MT, et al. Results from the CLUES study: a cluster randomized trial for the evaluation of cardiovascular guideline implementation in primary care in Spain. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):93.

Karlsson LO, Nilsson S, Bang M, Nilsson L, Charitakis E, Janzon M. A clinical decision support tool for improving adherence to guidelines on anticoagulant therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation at risk of stroke: a cluster-randomized trial in a Swedish primary care setting (the CDS-AF study). PLoS Med. 2018;15(3):e1002528.

Knappe S, Einsle F, Rummel-Kluge C, Heinz I, Wieder G, Venz J, et al. Niederschwellige leitlinienorientierte supportive Materialien (NILS) in der primärärztlichen Versorgung. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2018;64(3):14.

Luitjes SHE, Hermens R, de Wit L, Heymans MW, van Tulder MW, Wouters M. An innovative implementation strategy to improve the use of Dutch guidelines on hypertensive disorders in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2018;14:131–8.

Mellin C, Lexa M, Bryant AL, Mason S, Mayer DK. Antiemetic guidelines: using education to improve adherence and reduce incidence of CINV in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22(3):7.

Pauwels PPYT, Metsemakers JFM, Himawan AB, Kristina TN. The efficacy of education with the WHO dengue algorithm on correct diagnosing and triaging of dengue-suspected patients; Study in Public Health Centre. Hiroshima J Med Sci. 2018;67:6.

Pinto D, Heleno B, Rodrigues DS, Papoila AL, Santos I, Caetano PA. Effectiveness of educational outreach visits compared with usual guideline dissemination to improve family physician prescribing-an 18-month open cluster-randomized trial. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):120.

Presseau J, Mackintosh J, Hawthorne G, Francis JJ, Johnston M, Grimshaw JM, et al. Cluster randomised controlled trial of a theory-based multiple behaviour change intervention aimed at healthcare professionals to improve their management of type 2 diabetes in primary care. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):65.

Quanbeck A, Brown RT, Zgierska AE, Jacobson N, Robinson JM, Johnson RA, et al. A randomized matched-pairs study of feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of systems consultation: a novel implementation strategy for adopting clinical guidelines for Opioid prescribing in primary care. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):21.

Ranta A, Dovey S, Gommans J, Tilyard M, Weatherall M. Impact of general practitioner transient ischemic attack training on 90-day stroke outcomes: secondary analysis of a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27(7):2014–8.

Safatly I, Singleton H, Decker K, Roman C, Bystrzycki A, Mitra B. Emergency management of patients with Supratherapeutic INRs on Warfarin: a multidisciplinary education study. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2018;36(2):8.

Suman A, Schaafsma FG, van de Ven PM, Slottje P, Buchbinder R, van Tulder MW, et al. Effectiveness of a multifaceted implementation strategy compared to usual care on low back pain guideline adherence among general practitioners. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):358.

Sun A, Tsoh JY, Tong EK, Cheng J, Chow EA, Stewart SL, et al. A physician-initiated intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening in Chinese patients. Cancer. 2018;124(Suppl 7):1568–75.

Witt TJ, Deyo-Svendsen ME, Mason ER, Deming JR, Stygar KK, Rosas SL, et al. A model for improving adherence to prescribing guidelines for chronic opioid therapy in rural primary care. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2018;2(4):317–23.

Al KM. The influence of implementing nurse-led enteral nutrition guidelines on care delivery in the critically ill: a cohort study. Gastrointest Nurs. 2017;15(6):9.

Aloush SM. Does educating nurses with ventilator-associated pneumonia prevention guidelines improve their compliance? Am J Infect Control. 2017;45(9):969–73.

Coenen S, Weyts E, Jorissen C, De Munter P, Noman M, Ballet V, et al. Effects of education and information on vaccination behavior in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(2):318–24.

Cummings MJ, Goldberg E, Mwaka S, Kabajaasi O, Vittinghoff E, Cattamanchi A, et al. A complex intervention to improve implementation of World Health Organization guidelines for diagnosis of severe illness in low-income settings: a quasi-experimental study from Uganda. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):126.

Eccleston D, Horrigan M, Rafter T, Holt G, Worthley SG, Sage P, et al. Improving guideline compliance in Australia with a national percutaneous coronary intervention outcomes registry. Heart Lung Circ. 2017;26(12):1303–9.

Jordan KP, Edwards JJ, Porcheret M, Healey EL, Jinks C, Bedson J, et al. Effect of a model consultation informed by guidelines on recorded quality of care of osteoarthritis (MOSAICS): a cluster randomised controlled trial in primary care. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2017;25(10):1588–97.

Kersten FAM, Nelen W, van den Boogaard NM, van Rumste MM, Koks CA, IntHout J, et al. Implementing targeted expectant management in fertility care using prognostic modelling: a cluster randomized trial with a multifaceted strategy. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(8):1648–57.

Lesuis N, van Vollenhoven RF, Akkermans RP, Verhoef LM, Hulscher ME, den Broeder AA. Rheumatologists’ guideline adherence in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised controlled study on electronic decision support, education and feedback. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;36(1):8.

Liebschutz JM, Xuan Z, Shanahan CW, LaRochelle M, Keosaian J, Beers D, et al. Improving adherence to long-term opioid therapy guidelines to reduce opioid misuse in primary care: a cluster-randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1265–72.

Lilih S, Pereboom M, van der Hoeven RT, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Becker ML. Improving the effectiveness of drug safety alerts to increase adherence to the guideline for gastrointestinal prophylaxis. Int J Med Inform. 2017;97:139–44.

Lin LA, Bohnert ASB, Kerns RD, Clay MA, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA. Impact of the opioid safety initiative on opioid-related prescribing in veterans. Pain. 2017;158(5):833–9.

Lowe B, Piontek K, Daubmann A, Harter M, Wegscheider K, Konig HH, et al. Effectiveness of a stepped, collaborative, and coordinated health care network for somatoform disorders (Sofu-Net): a controlled cluster cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2017;79(9):1016–24.

Patil VM, Noronha V, Joshi A, Ramaswamy A, Gupta S, Sahu A, et al. Adherence to and implementation of ASCO antiemetic guidelines in routine practice in a tertiary cancer center in India. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(6):e574–e81.

Tahvonen P, Oikarinen H, Niinimaki J, Liukkonen E, Mattila S, Tervonen O. Justification and active guideline implementation for spine radiography referrals in primary care. Acta Radiol. 2017;58(5):586–92.

Trietsch J, van Steenkiste B, Grol R, Winkens B, Ulenkate H, Metsemakers J, et al. Effect of audit and feedback with peer review on general practitioners’ prescribing and test ordering performance: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):53.

Tunney RK Jr, Johnson DC, Wang L, Cox ZL. Impact of pharmacist intervention to increase compliance with guideline-directed statin therapy during an acute coronary syndrome hospitalization. Ann Pharmacother. 2017;51(5):7.

Vander Weg MW, Holman JE, Rahman H, Sarrazin MV, Hillis SL, Fu SS, et al. Implementing smoking cessation guidelines for hospitalized veterans: cessation results from the VA-BEST trial. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;77:79–88.

Wright SM. Using evidence-based practice and an educational intervention to improve vascular access management: a pilot project. Nephrol Nurs J. 2017;44(5):14.

Aakhus E, Granlund I, Odgaard-Jensen J, Oxman AD, Flottorp SA. A tailored intervention to implement guideline recommendations for elderly patients with depression in primary care: a pragmatic cluster randomised trial. Implement Sci. 2016;11:32.

Almatar M, Peterson GM, Thompson A, McKenzie D, Anderson T, Zaidi ST. Clinical pathway and monthly feedback improve adherence to antibiotic guideline recommendations for community-acquired pneumonia. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159467.

Bautista M, Llinas A, Bonilla G, Mieth K, Diaz M, Rodriguez F, et al. Thromboprophylaxis after major orthopedic surgery: improving compliance with clinical practice guidelines. Thromb Res. 2016;137:113–8.

Bhushan R, Lebwohl MG, Gottlieb AB, Boyer K, Hamarstrom E, Korman NJ, et al. Translating psoriasis guidelines into practice: important gaps revealed. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(3):544–51.

Chen HJ, Huang N, Chen LS, Chou YJ, Li CP, Wu CY, et al. Does pay-for-performance program increase providers adherence to guidelines for managing hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infection in Taiwan? PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0161002.

Goodfellow J, Agarwal S, Harrad F, Shepherd D, Morris T, Ring A, et al. Cluster randomised trial of a tailored intervention to improve the management of overweight and obesity in primary care in England. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):77.

Hinds A, Lopez D, Rascati K, Jokerst J, Srinivasa M. Adherence to the 2013 blood cholesterol guidelines in patients with diabetes at a PCMH: comparison of physician only and combination physician/pharmacist visits. Diabetes Educ. 2016;42(2):228–33.

Hogli JU, Garcia BH, Skjold F, Skogen V, Smabrekke L. An audit and feedback intervention study increased adherence to antibiotic prescribing guidelines at a Norwegian hospital. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:96.

Krassioukov A, Tomasone JR, Pak M, Craven BC, Ghotbi MH, Ethans K, et al. “The ABCs of AD”: a prospective evaluation of the efficacy of an educational intervention to increase knowledge of autonomic dysreflexia management among emergency health care professionals. J Spinal Cord Med. 2016;39(2):190–6.

Lu MT, Rosman DA, Wu CC, Gilman MD, Harvey HB, Gervais DA, et al. Radiologist point-of-care clinical decision support and adherence to guidelines for incidental lung nodules. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13(2):156–62.

Mader EM, Fox CH, Epling JW, Noronha GJ, Swanger CM, Wisniewski AM, et al. A practice facilitation and academic detailing intervention can improve cancer screening rates in primary care safety net clinics. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(5):533–42.

Paulus F, Binnekade JM, Middelhoek P, Vroom MB, SchuItz MJ. Guideline implementation powered by feedback and education improves manual hyperinflation performance. Nurs Crit Care. 2016;21(1):36–43.

Riis A, Jensen CE, Bro F, Maindal HT, Petersen KD, Bendtsen MD, et al. A multifaceted implementation strategy versus passive implementation of low back pain guidelines in general practice: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):143.

Sacco TL, LaRiccia B. Interprofessional implementation of a pain/sedation guideline on a trauma intensive care unit. J Trauma Nurs. 2016;23(3):156–64.

Thomas S, Mackintosh S. Improvement of physical therapist assessment of risk of falls in the hospital and discharge handover through an intervention to modify clinical behavior. Phys Ther. 2016;96(6):10.

Vellinga A, Galvin S, Duane S, Callan A, Bennett K, Cormican M, et al. Intervention to improve the quality of antimicrobial prescribing for urinary tract infection: a cluster randomized trial. CMAJ. 2016;188(2):108–15.

Barnes ER, Theeke LA, Mallow J. Impact of the provider and healthcare team adherence to treatment guidelines (PHAT-G) intervention on adherence to national obesity clinical practice guidelines in a primary care centre. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21(2):300–6.

de Beurs DP, de Groot MH, de Keijser J, Mokkenstorm J, van Duijn E, de Winter RF, et al. The effect of an e-learning supported Train-the-Trainer programme on implementation of suicide guidelines in mental health care. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:446–53.

Bouaud J, Spano J-P, Lefranc J-P, Cojean-Zelek I, Blaszka-Jaulerry B, Zelek L, et al. Physicians’ attitudes towards the advice of a guideline-based decision support system: a case study with OncoDoc2 in the management of breast cancer patients. MEDINFO. 2015;6:264–9.

Breimaier HE, Halfens RJ, Lohrmann C. Effectiveness of multifaceted and tailored strategies to implement a fall-prevention guideline into acute care nursing practice: a before-and-after, mixed-method study using a participatory action research approach. BMC Nurs. 2015;14:18.

Elder KG, Lemon SK, Costello TJ. Increasing compliance with national quality measures for stroke through use of a standard order set. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(11 Suppl 1):S6–S10.

Erickson KJ, Monsen KA, Attleson IS, Radosevich DM, Oftedahl G, Neely C, et al. Translation of obesity practice guidelines: measurement and evaluation. Public Health Nurs. 2015;32(3):222–31.

Gervera K, Graves BA. Integrating diabetes guidelines into a telehealth screening tool. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2015;12(Summer):37.

Giuliani S, McArthur A, Greenwood J. Preoperative fasting among burns patients in an acute care setting: a best practice implementation project. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13(11):235–53.

Guder G, Stork S, Gelbrich G, Brenner S, Deubner N, Morbach C, et al. Nurse-coordinated collaborative disease management improves the quality of guideline-recommended heart failure therapy, patient-reported outcomes, and left ventricular remodelling. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(4):442–52.

Liddy C, Hogg W, Singh J, Taljaard M, Russell G, Deri Armstrong C, et al. A real-world stepped wedge cluster randomized trial of practice facilitation to improve cardiovascular care. Implement Sci. 2015;10:150.

Peiris D, Usherwood T, Panaretto K, Harris M, Hunt J, Redfern J, et al. Effect of a computer-guided, quality improvement program for cardiovascular disease risk management in primary health care: the treatment of cardiovascular risk using electronic decision support cluster-randomized trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(1):87–95.

Peter W, van der Wees PJ, Verhoef J, de Jong Z, van Bodegom-Vos L, Hilberdink WK, et al. Effectiveness of an interactive postgraduate educational intervention with patient participation on the adherence to a physiotherapy guideline for hip and knee osteoarthritis: a randomised controlled trial. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(3):274–82.

Shelton JB, Ochotorena L, Bennett C, Shekelle P, Kwan L, Skolarus T, et al. Reducing PSA-based prostate cancer screening in men aged 75 years and older with the use of highly specific computerized clinical decision support. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1133–9.

Sherrard H, Duchesne L, Wells G, Kearns SA, Struthers C. Using interactive voice response to improve disease management and compliance with acute coronary syndrome best practice guidelines: a randomized controlled trial. Can J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;25(1):6.

Terasaki J, Singh G, Zhang W, Wagner P, Sharma G. Using EMR to improve compliance with clinical practice guidelines for management of stable COPD. Respir Med. 2015;109(11):1423–9.

Ballesca MA, LaGuardia JC, Lee PC, Hwang AM, Park DK, Gardner MN, et al. An electronic order set for acute myocardial infarction is associated with improved patient outcomes through better adherence to clinical practice guidelines. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):155–61.

Cabilan CJ, Hines SJ, Chang A. Managing peripheral intravenous devices in the adults’ general surgical setting: a best practice implementation report. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2014;12(1):25–30.

Cahill NE, Murch L, Cook D, Heyland DK, Group ObotCCCT. Implementing a multifaceted tailored intervention to improve nutrition adequacy in critically ill patients: results of a multicenter feasibility study. Crit Care. 2014;19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-35

van Dijk MK, Oosterbaan DB, Verbraak MJ, Hoogendoorn AW, Penninx BW, van Balkom AJ. Effectiveness of the implementation of guidelines for anxiety disorders in specialized mental health care. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;132(1):69–80.

Franx G, Huyser J, Koetsenruijter J, Feltz-Cornelis CM, Verhaak PF, Grol RP, et al. Implementing guidelines for depression on antidepressant prescribing in general practice: a quasi-experimental evaluation. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:169.

Gupta A, Ip IK, Raja AS, Andruchow JE, Sodickson A, Khorasani R. Effect of clinical decision support on documented guideline adherence for head CT in emergency department patients with mild traumatic brain injury. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e2):e347–51.

Mold JW, Aspy CB, Smith PD, Zink T, Knox L, Lipman PD, et al. Leveraging practice-based research networks to accelerate implementation and diffusion of chronic kidney disease guidelines in primary care practices: a prospective cohort study. Implement Sci. 2014;9:11.

Peng B, Ni J, Anderson CS, Zhu Y, Wang Y, Pu C, et al. Implementation of a structured guideline-based program for the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke in China. Stroke. 2014;45(2):515–9.

Pimenta HB, Caldeira AP, Mamede S. Effects of 2 educational interventions on the management of hypertensive patients in primary health care. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2014;34(4):243–51.

Santos M, Tygesen H, Eriksson H. Clinical decision support system (CDSS) – effects on care quality. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2014;27(8):12 MCB University Press.

Sonstein L, Clark C, Seidensticker S, Zeng L, Sharma G. Improving adherence for management of acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 2014;127(11):1097–104.

Grol R, Wensing M. What drives change? Barriers to and incentives for achieving evidence-based practice. Med J Aust. 2004;180(S6):S57–60.

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(1):13–24.

Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, O'Connor D, Patey A, Ivers N, et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):77.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Qual Health Care. 1998;7(3):149–58.

Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behaviour. New York: Wiley; 1975.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Press; 2003.

May C, Finch T. Implementing, embedding and integrating practices: an outline of normalization process theory. Sociology. 2009;43(3):535–54.

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–7.

Michie S, Atkins L, West R. A guide to using the behaviour change wheel. London: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, Craig P, Baird J, Blazeby JM, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2021;374. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2061

Fischer F, Lange K, Klose K, Greiner W, Kraemer A. Barriers and strategies in guideline implementation-a scoping review. Healthcare (Basel). 2016;4(3).

Chan WV, Pearson TA, Bennett GC, Cushman WC, Gaziano TA, Gorman PN, et al. ACC/AHA special report: clinical practice guideline implementation strategies: a summary of systematic reviews by the NHLBI Implementation Science Work Group: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(8):1076–92.

Spoon D, Rietbergen T, Huis A, Heinen M, van Dijk M, van Bodegom-Vos L, et al. Implementation strategies used to implement nursing guidelines in daily practice: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;111:103748.

Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, Shaw EJ, Cheater F, Flottorp S, et al. Tailored interventions to address determinants of practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD005470.

Boaz A, Hanney S, Borst R, O'Shea A, Kok M. How to engage stakeholders in research: design principles to support improvement. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):60.

Bombard Y, Baker GR, Orlando E, Fancott C, Bhatia P, Casalino S, et al. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):98.

Forsetlund L, O'Brien MA, Forsen L, Reinar LM, Okwen MP, Horsley T, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;9:CD003030.

Johnson MJ, May CR. Promoting professional behaviour change in healthcare: what interventions work, and why? A theory-led overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2015;5(9):e008592.

McGowan J, Straus S, Moher D, Langlois EV, O'Brien KK, Horsley T, et al. Reporting scoping reviews-PRISMA ScR extension. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;123:177–9.

Acknowledgements

Members of the Guidelines International Network reviewed this manuscript to further refine the interpretation of findings and enhance communication of the findings. The Guidelines International Network (GIN) is an international not-for-profit association of organizations and individuals involved in the development and use of clinical practice guidelines. GIN is a Scottish Charity, recognized under Scottish Charity Number SC034047. More information on the Network and its activities are available on its website: www.g-i-n.net. This paper/presentation reflects the views of its authors, and the Guidelines International Network is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Funding

The Guidelines International Network (GIN; www.g-i-n.net), which is a Scottish Charity, recognized under Scottish Charity Number SC034047, provided support for collaboration of the authors. The GIN Board of Trustees had an opportunity to comment on this paper, but did not have any role in development or preparation of the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (SP, KS, SB, AR, JM, PG, ES, MC, ZM, TK, LPR, EN, LK, SA, YSM, & AG) were involved in the design of the study. SP, SB, AR, JM, PG, ES, MC, ZM, and AG screened titles and abstracts. SP, KS, PG, TK, SB, JM, MC, ZM, EN, AR, LPR, ES, LK, and AG extracted data. SP and AG wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors approved the final version.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist.

Additional file 2.

Eligibility criteria.

Additional file 3.

Search strategy.

Additional file 4.

Data extraction table.

Rights and permissions