Abstract

Background

Guidelines support health care decision-making and high quality care and outcomes. However, their implementation is sub-optimal. Theory-informed, tailored implementation is associated with guideline use. Few guideline implementation studies published up to 1998 employed theory. This study aimed to describe if and how theory is now used to plan or evaluate guideline implementation among physicians.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted. MEDLINE, EMBASE, and The Cochrane Library were searched from 2006 to April 2016. English language studies that planned or evaluated guideline implementation targeted to physicians based on explicitly named theory were eligible. Screening and data extraction were done in duplicate. Study characteristics and details about theory use were analyzed.

Results

A total of 1244 published reports were identified, 891 were unique, and 716 were excluded based on title and abstract. Among 175 full-text articles, 89 planned or evaluated guideline implementation targeted to physicians; 42 (47.2%) were based on theory and included. The number of studies using theory increased yearly and represented a wide array of countries, guideline topics and types of physicians. The Theory of Planned Behavior (38.1%) and the Theoretical Domains Framework (23.8%) were used most frequently. Many studies rationalized choice of theory (83.3%), most often by stating that the theory described implementation or its determinants, but most failed to explicitly link barriers with theoretical constructs. The majority of studies used theory to inform surveys or interviews that identified barriers of guideline use as a preliminary step in implementation planning (76.2%). All studies that evaluated interventions reported positive impact on reported physician or patient outcomes.

Conclusions

While the use of theory to design or evaluate interventions appears to be increasing over time, this review found that one half of guideline implementation studies were based on theory and many of those provided scant details about how theory was used. This limits interpretation and replication of those interventions, and seems to result in multifaceted interventions, which may not be feasible outside of scientific investigation. Further research is needed to better understand how to employ theory in guideline implementation planning or evaluation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Clinical practice guidelines are widely developed to inform and augment health care policy, planning, delivery, evaluation, and quality improvement. Guidelines offer many potential benefits to patients, health care professionals, and health systems by supporting decision-making and enhancing the efficiency and quality of health services, while reducing practice variation [1]. However, numerous population-based studies have shown that guideline implementation is complex and challenging [2, 3] due to the influence of numerous, multilevel (patient, provider, team, organization, system), often competing factors [4]. Considerable research has been undertaken over the last three decades to identify effective single or multifaceted interventions for implementing guidelines [5–7]. While many of those interventions are promising, their impact on health care delivery and outcomes has been modest and inconsistent [8, 9]. Given the important role of guidelines in translating scientific evidence to practice, further research is needed to generate knowledge on how to optimize guideline implementation and use.

To address this need, the field of implementation science has pursued research in two predominant themes. One theme focused on elaborating and refining the guideline implementation planning process so that the most promising interventions for a given context are employed [10]. Another theme focused on identifying the interventions and active components of interventions that are associated with effective guideline implementation so that, when employed, they result in beneficial impact. In 2005, a Cochrane systematic review by Shaw et al. found that guideline implementation interventions selected and tailored according to the advance identification of potential barriers of guideline use were more likely to improve professional practice compared with either no intervention or the dissemination of guidelines [11], and this was supported by subsequent research [12]. As a result, implementation scientists advocated for choosing and adapting interventions based on mapping pre-identified determinants, including barriers and facilitators of guideline use, with theoretical constructs [12]. Theories (or models or frameworks) suggest how determinants influence the association between processes and outcomes and provide insight on interventions (approaches, strategies) that overcome determinants and/or support processes associated with desirable outcomes [13].

However, guideline developers, implementers, researchers, or others may not be using theory when planning or undertaking guideline implementation. A systematic review published in 2010 by Davies et al., based on controlled trials, before-after studies and interrupted time series that evaluated any guideline dissemination or implementation strategy targeting physicians and reported objective measures of provider behavior and/or patient outcomes, found that only 6.0% (14/235) of studies of guideline implementation planning or evaluation were explicitly based on theory [14]. Those studies were published from 1976 to 1998, well before knowledge was published of the need to tailor interventions to identified determinants of guideline use [11]. Hence, guideline developers, implementers, researchers or others may not be aware of, or be employing the most relevant theories from among the multitude that are available [15], or may not understand how to use theory when interpreting identified determinants, or choosing or tailoring interventions [16]. Theory may be more commonly used in recently published research, although this is unknown. Furthermore, recent rigorous studies that evaluated tailored, theory-based interventions in various health care contexts have failed to consistently demonstrate a beneficial impact on physician use of guidelines or patient outcomes [17, 18]. Theory use may be sub-optimal, but without further analysis of such studies, this too is unknown.

Considerable resources continue to be invested in the development of guidelines that are not achieving the maximum benefit of which they are capable, potentially due to limitations in the way they are implemented. Further research is needed to understand if theory is being used to plan, undertake, and evaluate guideline implementation. In particular, greater insight is needed on how theory was employed in guideline implementation research. This may reveal the need for interventions to promote awareness, knowledge, and skill in the use of theories for guideline implementation, or for further research on how to use theory in guideline implementation. The purpose of this scoping review was to summarize current research in the field of guideline implementation to describe if and how theory has been used to plan or evaluate the implementation and use of guidelines among physicians, who are frequently the target users of guidelines.

Methods

Approach

This review sought to identify theories that were used to plan or evaluate guideline implementation targeted to physicians, reveal rationale for choice of theory as is required by the Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) reporting standards for studies that evaluate behavioral interventions [19] and describe how theory was used. Therefore, rather than a traditional systematic review that seeks to describe outcomes, a five-step scoping review was chosen: scoping, searching, screening, data extraction, and data analysis [20]. This approach was employed to acquire an understanding of the extent, range, and nature of research on this topic, and to describe if and how theory has been used to plan or evaluate guideline implementation. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria guided the conduct and reporting of this review [21]. Data were publicly available so institutional review board approval was not necessary. A protocol for this review was not registered.

Scoping

As per scoping methods standards, this step involved becoming familiar with the literature on this topic and generated eligibility criteria through consultation with the members of the international research team who are experienced guideline developers and implementers. A preliminary search was conducted in MEDLINE using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) including, but not limited to, diffusion of innovation or information dissemination and practice guidelines as topic or guideline adherence and a range of available terms that referred to theory (for example, models, theoretical). LL, ARG, SB, and RV screened titles and abstracts of the preliminary search results, which were used to plan a more comprehensive search strategy and to generate final eligibility criteria based on the PICO (population, intervention, comparisons, outcomes) framework. All members of the research team reviewed eligibility criteria and provided feedback, which was used to refine the eligibility criteria. The research team was comprised of guideline developers, implementation scientists, and systematic review methodologists.

Populations referred to practicing physicians of any type based in health care settings (e.g., hospitals, ambulatory clinics, community-based physician offices) who were target users of specifically named and referenced guidelines upon which implementation efforts were focused, either for guidelines newly developed, or to improve compliance with an existing guideline. Studies were included if the target users were of various professions provided that the majority were physicians. Guidelines referred to clinical practice guidelines, defined as statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care based on systematic review of evidence, for any form of test, procedure, or treatment for any condition or disease, that were specifically named and cited in eligible primary studies [22].

Interventions referred to guideline implementation processes or interventions in which theory was explicitly named, referenced, and used. Theory was defined as a set of analytical principles or statements including defined variables, a domain to which the theory applies, and a set of relationships between the variables and specific predictions [23]. Theory-informed frameworks or models were also considered. Interventions also referred to the strategies or processes that were chosen, tailored, implemented, or evaluated to promote or improve guideline use. Similar to the 2010 systematic review of the use of theory in guideline implementation [14], eligible studies used theory to (1) identify potential determinants of guideline use among target users with questionnaires or qualitative methods or analyze the findings of such studies; (2) choose or tailor interventions that would address identified determinants, either among the research team or through structured consultation with experts or stakeholders (Delphi, modified Delphi, nominal group, etc.); or (3) evaluate the impact of interventions, including studies that examined implementation (fidelity), guideline use (practice/behavior), or impact (patient, provider, organizational, or system-level outcomes).

Comparisons varied depending on the type of study. For example, in studies of type 1, identified determinants may have been similar or varied by specialty or practice setting. In type 2 studies, the choice of intervention or tailoring strategy may have been dependent on characteristics of the involved participants. Type 3 studies may have evaluated physicians with and without exposure to theory-based interventions, or before or after exposure to theory-based interventions, or receiving different types of theory-based interventions, or compared any type of theory-based intervention with any type of non-theory based intervention or control condition, where interventions may have been single or multifaceted.

Outcomes were those reported in eligible studies and were also relevant to study type: (1) perceived or experienced determinants of guideline use including recommended facilitators or interventions to promote guideline use; (2) recommended interventions or strategies to tailor interventions; and (3) any reported impact of guideline implementation.

Eligible study designs included English language qualitative (interviews, focus groups, qualitative case studies), quantitative (questionnaires, randomized controlled trials, time series, before-after studies, prospective or retrospective cohort studies, case control studies), or mixed methods studies (studies that integrated quantitative and qualitative data). Systematic reviews were not eligible but were used to identify additional eligible primary studies. Studies were not eligible if they:

-

involved trainee physicians, health care managers or policy-makers, or consumers (patients, families, caregivers, public) as target guideline users

-

were based on infection control, quality improvement, patient safety, client-centeredness, or organizational “best practices” but did not explicitly name and reference a guideline

-

were based on grounded theory technique (a qualitative approach) and did not analyze the findings using an explicitly named and referenced theory, model, or framework

-

searched for, described, developed, or synthesized theory without applying it to plan or evaluate guideline implementation

-

referenced a theory, model, or framework but made no further mention of it

-

were based in a school or sports setting

-

concluded that an intervention was needed to address lack of compliance with a guideline

-

or consisted of policy directives or strategies, consensus statements, guidelines, conference abstracts or proceedings, protocols, letters, editorials, or commentaries.

Searching

A final comprehensive search strategy compliant with the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies statement [24] was developed in consultation with a medical librarian (Additional file 1). MEDLINE, EMBASE, and The Cochrane Library were searched on April 26, 2016 for articles published from January 2006 to that date. The year 2006 was chosen because evidence supporting the need to choose and tailor interventions for implementing guidelines based on identified determinants [11] and relevant theories [12] was published by Shaw et al. in 2005. As noted, the references of systematic reviews were scanned to identify additional eligible articles.

Screening

For the ultimate search results, the screening of titles and abstracts according to specified eligibility criteria was independently piloted by LL, ARG, SB, and RV. LL and RV then independently screened titles and abstracts of all non-duplicate items. All items selected by at least one reviewer were retrieved for full-text screening. Full-text items were screened just prior to data extraction by LL in consultation with ARG. If more than one publication described a single study and reported different data, they were all included but counted as a single study.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed with input from the research team to collect information on study characteristics (author, publication year, country, design), condition/disease, physician specialty, guideline topic, aim (implement new guideline or improve compliance with existing guideline), theory (or model or framework) used, rationale for choice of theory as specified in individual studies (describes implementation or its determinants, used by others, validated, integrates many theories and/or constructs), and how theory was used (identify determinants, select/tailor interventions, evaluate impact of intervention) [14]. Qualitative details were extracted about how theory was used if provided. We did not access related studies previously published by the same authors that may have reported these details because reporting standards specify that theory underlying the development or evaluation of interventions should be specified when reporting research [19]. Details extracted about the intervention were based on the Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) reporting checklist and included content (information/knowledge conveyed), format (mode of delivery), timing (duration and/or frequency), participants (number, type, setting), and personnel (who delivered the intervention) [19]. Interventions were classified as single or multifaceted. Outcomes varied by study type: (1) identified determinants, (2) intervention chosen, and strategies or process for tailoring, and (3) impact of the intervention. LL and ARG independently pilot-tested data extraction on two articles and compared findings by discussion to refine the data extraction form. This was repeated two more times. The refined data extraction form was independently pilot-tested by LL, SB, and RV on five articles. LL extracted data from all articles, which was independently checked in by ARG, SB, and RV so that all were reviewed in duplicate.

Data analysis

Summary statistics (i.e., frequency, proportion) were used to describe the number of studies by year published, country, research design, guideline topic, and type of target user. Each unique theory (or model/framework) was listed, and summary statistics were used to report the frequency of use, rationale for use, and how theories were used. Theories were classified as classic (originating from fields external to implementation science such as psychology, sociology, organizational management) or implementation theories (developed de novo by implementation researchers or by adapting existing classic theories) [23]. Details about interventions that were evaluated and associated outcomes were charted (collated, synthesized, and interpreted) and summarized in a narrative format [25]. The quality of individual studies was not assessed because that is not customary for a scoping review. All co-authors reviewed the summary of findings, and their feedback was incorporated in the final version.

Results

Search results

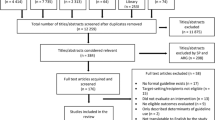

A total of 1244 studies were identified by searches, of which 891 were unique items, and 716 were excluded based on screening of titles and abstracts. Among 175 full-text articles that were screened, 123 were excluded because a theory, model, or framework was not named or referenced (47), target users were not predominantly physicians (25), the focus was not guideline implementation (20), a guideline was not named or referenced (18), or because the publication type was not eligible (13). An additional 12 studies were excluded because they were systematic reviews, from which 2 eligible studies were identified among references to primary studies. A total of 42 studies were included in the review (Fig. 1). While 42 studies were included in this review because they did employ a theory, of 123 full-text studies that were excluded, 47 were excluded because they were otherwise eligible but did not employ a theory. Therefore, of 89 studies that planned or evaluated guideline implementation targeted to physicians, 47.2% were based on theory. Data extracted from included studies are available in Additional file 2 [26–67].

Study characteristics

Studies were published between 2006 and 2015. The number of studies published per year increased almost annually from 2006 to 2013 and then declined in 2014 and again in 2015 (Fig. 2). Studies were conducted in the United Kingdom (10, 23.8%), Australia (9, 21.4%), the United States (7, 16.7%), the Netherlands (6, 14.3%), Canada (3, 7.1%), Iran (3, 7.1%), Argentina (1, 2.4%), Belgium (1, 2.4%), Germany (1, 2.4%), and Saudi Arabia (1, 2.4%). Most studies used a single cohort design (34, 81.0%). Of these, 18 employed questionnaires, 10 used interviews, 3 were based on focus groups, 2 were before-after evaluations of an intervention, and 1 described the intervention that was employed. The remainder (7, 16.7%) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and one mixed methods study (2.4%).

Guidelines

Guidelines targeted in included studies pertained to a wide variety of health care topics. The diseases or conditions most frequently addressed included asthma (5, 11.9%), mental health (4, 9.5%), antibiotic prescription (3, 7.1%), coronary heart disease (3, 7.1%), diabetes (3, 7.1%), and osteoarthritis (3, 7.1%). The remaining studies targeted various health care issues. The majority of studies were planning or evaluating the implementation of an existing guideline to improve compliance (38, 90.5%) rather than planning or evaluating the implementation of a newly developed guideline.

Target users

The users most frequently targeted were general practitioners (17, 40.5%) followed by multidisciplinary groups of physicians (14, 33.3%). The remaining studies targeted various physician specialties (11, 26.2%).

Theories used

Table 1 summarizes the number and type of theories used in included studies. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), a classic theory (16, 38.1%), and the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF), an implementation theory (10, 23.8%), were the most frequently used theories. Normalization Process Theory, an implementation theory, was used in two studies [29, 32]. Other theories employed were all classic in origin and included Diffusion of Innovation Theory [49, 61, 65], Social Cognitive Theory [58, 60], Adult Learning Theory [33], Social Marketing Theory [39], Social Learning Theory [55], Self-Perception Theory [60], and Fuzzy-Trace Theory [67]. Several studies used models (6, 14.3%) or frameworks (4, 9.5%). Models or frameworks used more than once included the Cabana Framework of Barriers to Physician Guideline Adherence [44, 52, 56] and the Attitude Social Norm Self Efficacy model [43, 53]. Some studies used a combination of two or more theories, models, or frameworks [40, 55, 60], two of which used one or both of the TPB or TDF [40, 55].

Rationale for theories selected

Several studies (7, 16.7%) referenced a theory, model, or framework but provided no rationale for its selection. Most studies (33, 83.3%) provided an explanation for the choice of theory, model, or framework employed. Rationales were grouped into four categories that emerged from the data. The theory (or model/framework) describes implementation, or its determinants was the rationale referred to by most (31/35, 88.6%) studies, for example, “The constructs of the TPB can be used as a framework to explore theoretically derived determinants of behavior” [38]. Other studies that provided this rationale were less clear, for example, theories “address both the how and why of change” [55]. Some studies explicitly stated that the theory (or model/framework) was previously used by others (17/35, 48.6%) or had been validated (14/35, 40.0%), for example, “The TDF has been validated and used in multiple health care settings to assist with the systematic identification of barriers and enablers to implementation” [26]. Other studies noted that the theory was chosen because it integrated many theories or theoretical constructs (5/35, 14.3%), for example, “The TDF aims to synthesize a multitude of coherent behavior change theories into a single framework that allows assessment and explanation of behavioral problems and associated barriers and enablers, and inform the design of appropriately targeted interventions” [36]. Overall, while many studies provided more than one rationale (24/35, 68.6%), in most cases the reasons were not explicitly linked with identified barriers or facilitators of guideline use so that the reader could clearly understand how theoretical constructs predicted or explained context-specific conditions that challenged guideline implementation.

How theories were used

Table 1 summarizes how theories were used in included studies. The majority of studies were type 1 (32, 76.2%). These studies used theory to identify determinants of guideline use as a preliminary step in guideline implementation planning. Of these, 15 studies used theory to inform survey questions, while 4 studies used theory to analyze survey findings. Another 6 type 1 studies used theory to inform questions that were used during qualitative interviews or focus groups; 6 studies used theory to analyze interview or focus group findings; and 1 study used theory to both inform interview questions and to analyze the findings that emerged from those interviews. Among the 32 type 1 studies, the most frequently used theories (or models/frameworks) were the TPB (14), TDF (7), Cabana Framework of Barriers to Physician Guideline Adherence (3), and the Diffusion of Innovations Theory (2).

Two studies (4.8%) were type 2 [33, 53]. This type of study used theory to select and/or tailor interventions but did not proceed to evaluate the impact of interventions. They both proposed multifaceted interventions. One study employed the Attitude Social Norm Self Efficacy model to analyze the findings of physician interviews about depression guidelines [53]. Identified determinants of guideline use then informed the selection and design of a multifaceted intervention as part of a systematic intervention mapping process. The proposed intervention included educational meetings, educational materials, audit and feedback, and ongoing training. Another study employed the TDF and Adult Learning Theory to design an intervention comprised of 4 workshops of 1 or 2h, delivered from 2 to 3 weeks apart and including didactic, interactive, and role play components plus intervening videos of simulated patient consultations to improve the management of osteoarthritis [33].

Several studies were type 3 (8, 19.0%). These studies evaluated the impact of interventions. One study did not report how theory (Diffusion of Innovation) was used [61]. The remainder employed a range from one to three theories (or models/frameworks). No theory (or model/framework) predominated; they included Normalization Process Theory [32], TDF [40], Social Marketing Theory [39], TPB [40, 55], Social Learning Theory [55], Social Cognitive Theory [58, 60], Elaboration Likelihood Model [60], Self-Perception Theory [60], Diffusion of Innovation Theory [61], and Social Influence Theory [64]. In type 3 studies, theories were used in different ways including to design interventions [39, 55, 58, 60, 64], to select interventions [40, 58, 60], to identify determinants [40, 58], and to evaluate the findings of interviews that probed for the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention [32, 55]. One study that used theory to identify determinants and select and design the intervention did so through use of a formal intervention mapping process [58].

Interventions evaluated

Additional file 3 provides details on the eight type 3 studies that evaluated the impact of interventions, which were selected, designed, and/or evaluated based on theories (or models/frameworks) [32, 39, 40, 55, 58, 60, 61, 64]. Two of those studies, both randomized controlled trials, evaluated single interventions [40, 60]. One was based on a mixed didactic and interactive educational workshop on the management of low back pain and employed the TDF and TPB [40]. It found that intervention group physicians had significantly greater intention of complying with the guideline for X-ray referral, adhered with guideline recommendations for X-ray referral, and were more likely to give advice to stay active; there were no differences between intervention and control physicians with respect to referral for imaging. Another study addressed smoking cessation counseling and employed Social Cognitive Theory, Self-Perception Theory, and Elaboration Likelihood Model [60]. It included three intervention arms, each based on a different single intervention including educational information, a quiz with educational information provided as answers, and feedback of self-reported performance data. Compared with control, only those in the educational information group reported significantly higher intention and more frequently recommending smoking cessation.

Six studies, including two qualitative studies embedded in RCTs [32, 55], two single cohort before-after studies [39, 58], and two RCTs [61, 64] evaluated multifaceted interventions. Two qualitative studies assessed the implementation fidelity of interventions. In one, which employed Normalization Process Theory, participating GPs who were interviewed identified several benefits of the intervention, comprised of a series of four workshops including didactic, interactive, and role play components [32]. They said that they better understood how to apply osteoarthritis guidelines and were comfortable with the clinical intervention that included a guidebook for patients and referral to nurse-led clinics. In the other qualitative study, which employed TPB and Social Learning Theory, based on a trial of a seven-part intervention that included online modules and an in-person seminar, interviewed GPs reported improved self-efficacy and changes in consultation style and antibiotic prescribing [55]. Participants appreciated receiving current scientific evidence and their own performance data.

Two single cohort studies both achieved positive impact. Educational outreach plus educational information significantly increased physician knowledge, intent to use venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, and number of patients receiving VTE prophylaxis in a study that employed Social Marketing Theory [39]. Educational outreach plus educational information, together with appeals to professional associations, formulary systems, and mass media significantly increased intent to prescribe diuretics for hypertension management in a study that employed Social Cognitive Theory [58].

Two RCTs also reported positive impact. One RCT, which employed Diffusion of Innovation Theory and engaged birth attendants as opinion leaders who disseminated guidelines, provided training, and generated and shared monthly performance data [61]. Readiness to change and prophylactic use of oxytocin increased significantly, and the rate of episiotomy decreased significantly in intervention hospitals compared with control hospitals. In a second RCT of educational outreach visits, which employed Social Influence Model of Behavior Change, computer reminders, telephone follow-up, and a financial incentive, screening, the number of skin tests, detection of active cases of tuberculosis, referral of patients with tuberculosis, and use of vaccine increased significantly in intervention practices compared with control practices [64].

Discussion

This study was conducted to understand if and how theory (or models/frameworks) was used to plan or evaluate guideline implementation, as has been advocated [11, 12]. Of 89 studies that planned or evaluated guideline implementation targeted to physicians, nearly half (42, 47.2%) were based on theory and included in this scoping review. This compares favorably with the Davies et al. 2010 review that reported explicit theory use in 6.0% of guideline implementation studies published from 1976 to 1998 [14]. There does appear to be an upward trend because, in our review, the number of published studies meeting our inclusion criteria increased almost yearly and represented a wide array of countries, guideline topics, and types of target physicians. However, many studies were excluded because they did not use theory, several studies cited theory but made no further mention of it, and not all studies of each type (identify determinants, select/tailor interventions, evaluate interventions) employed theory or explicitly linked pre-identified determinants of guideline use with theory. Overall, theory was not used consistently and transparently in guideline implementation.

A few issues may limit the interpretation and use of these findings. Although we searched the most relevant databases of medical literature pertaining to physicians with a search that complied with standards [24] and employed rigorous searching and screening processes, we may not have identified all relevant studies. We focused on physicians, who are key target users of guidelines, as did the prior Davies et al. study of theory use in guideline implementation [14] and therefore potentially excluded relevant studies in which non-physicians were target users. Whether these results transfer to other health professionals requires investigation. Publication bias, or the tendency for journals to publish trials with positive results or surveys with high response rates, may have influenced the number and type of studies that were retrieved and the largely positive impact of eligible studies that evaluated interventions. We did not thoroughly discuss the impact of interventions because the purpose of this scoping review was not to assess the effectiveness of interventions, but to describe how theory was used when planning or evaluating guideline implementation.

Several notable findings emerged from this review. While use of theory to plan or evaluate guideline implementation increased subsequently to the review published in 2010 by Davies et al. [14], many studies were not based on theory, or cited theory but made no further mention of how it was used. A previous systematic review of 32 studies published from 2004 to 2013 that evaluated the implementation of guidelines for arthritis, diabetes, colorectal cancer, and heart failure also found that few studies rationalized intervention choice by referring to models, frameworks, or theories (6/32, 18.8%) [68]. Another systematic review of 57 studies published from 1990 to 2000 evaluated the adoption of health care innovations, including guidelines and reported that none of the studies employed theory [69]. Other researchers have also found limited use of theory to design or evaluate public health interventions [70], to inform the implementation of guidelines targeted to community pharmacists [71] or to plan interventions targeted to the allied health professions [72]. Theory-driven implementation is considered a required standard, yet many intervention developers are not using theory. Further research is needed to establish whether those who implement guidelines are familiar with theories and how to apply them. Such research could also examine if education or discipline of the implementers are associated with use of theory, and whether or not including health services researchers are familiar with theory to guideline teams improves theory-informed implementation.

Another key finding is that, while most studies justified the selection of theories, the rationales provided were lacking in specificity and failed to explicitly link identified context-specific determinants with particular theoretical constructs. This too has been identified by others in various health care contexts. For example, in a systematic review of 62 studies that used theory to design or evaluate public health interventions, descriptions of theory development and use in intervention design and evaluation lacked detail [70]. Another systematic review of 32 studies that evaluated interventions targeted to allied health professionals reported that most studies did not describe how the interventions were developed or their underlying mechanism of action [72]. The Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) criteria for reporting of knowledge translation interventions [19] and the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist for better reporting of interventions [73] both recommend the inclusion of the rationale, theory, or change process that underpins an intervention as this can help others to know which elements are essential, rather than optional or incidental [73]. Intervention mapping, used by only two studies included in this review [53, 58], is an increasingly used process for engaging stakeholders in choosing and designing theory-based interventions [74, 75]. It offers a systematic and explicit process for mapping identified determinants to program objectives, and selecting evidence- and theory-informed interventions likely to achieve those objectives, which may help intervention developers to better report how theory was used. Further research is needed to understand whether guideline implementers are aware of reporting criteria such as WIDER and TIDieR, or processes such as intervention mapping. However, while all of these resources specify that the use of theory and its rationale are needed and should be explicit, they do not actually provide guidance on how to choose and apply theory. Thus, the development of more detailed reporting guidance specific to the use of theory is needed.

This review found that all eight studies that evaluated the impact of interventions achieved positive impact on the outcomes reported. Yet, many others have not [15, 16]. A recent process evaluation of five failed trials that evaluated theory-based tailored interventions for guideline implementation found that only some of the determinants targeted by the intervention were relevant to participants who identified many new barriers that were not addressed by the intervention [76]. It may be that pre-determined barriers do not cover all factors that potentially affect implementation outcomes; that other strategies for identifying barriers and facilitators are necessary; that the removal of one barrier may create another one; and that the complex interplay among various barriers and facilitators cannot always be predicted despite best efforts for doing so [77]. These issues raise several implications—is the use of a standardized theory-driven approach to implementation planning problematic because it cannot accommodate the reality of the fluidity of barriers and facilitators? Or are theories from a variety of disciplines needed that differ from those that have been historically used to account for the complexity of implementation? Or is there a limit as to what we can expect from theory? Further research is needed to more fully understand why theory-informed interventions fail to consistently achieve desired outcomes and to address these related questions.

Based on the studies in our review that proposed or evaluated an intervention, it appears that the use of theory commonly gives rise to multifaceted interventions. In other research, a meta-review of 25 systematic reviews that compared direct and indirect effect size and dose-response of single and multifaceted strategies showed no benefit of multifaceted over single strategies [78]. Similar findings emerged from a systematic review of studies that evaluated the implementation of neck and/or back pain guidelines [79]. These findings contrast with the prevalent use of theory-informed multifaceted guideline implementation interventions by studies included in this review. In comparison with single interventions, multifaceted interventions may be more expensive, may place a higher burden on those delivering and receiving the intervention, and may not be easily replicable outside of the context of scientific investigation. Therefore, further research is needed to better understand how to employ theory when designing or evaluating guideline implementation so that interventions are feasible and can be more readily scaled up if found to be effective, which is the ultimate end-goal of implementation science.

TPB and TDF emerged as the most commonly used theories giving rise to multifaceted interventions. These were chosen because they had been used by others and because they addressed a broad range of determinants, rather than explicitly matching pre-identified determinants to specific theory chosen from among the many that are available. Therefore, guideline implementers may benefit from information about theories and how to use them. To supply this information, research is needed to more firmly establish which theories and how many theories (or models/frameworks) result in effective interventions. In addition, educational interventions may be needed to enhance guideline implementer awareness of existing compilations of theories from various disciplines [15, 80–83].

Conclusions

This scoping review of studies published from 2006 to 2015 that planned or evaluated guideline implementation targeted to physicians found that nearly half were based on theory (or models/frameworks). This compared favorably with previous studies. The majority of studies employed the TPB or the TDF and used theory to inform survey or interview questions that identified determinants of guideline use. Positive outcomes were achieved by the few studies that evaluated interventions, the majority of which were multifaceted. However, most studies provided few details about why the theory was chosen or how it was used and, in particular, did not explicitly link pre-identified determinants of guideline use to specific theoretical constructs. Further research is needed to assess awareness and knowledge of theory among guideline implementers, to develop a more detailed guidance on the use and reporting of theory-informed implementation, to establish the number of types of theories that result in improved guideline use, to understand why theory-informed interventions fail to consistently achieve desired outcomes, and to generate insight on how to design theory-based interventions that are feasible to broadly apply outside of the research context.

References

Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchison A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical practice guidelines. The potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318:527–30.

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. NEJM. 2003;348:2635–45.

Sheldon TA, Cullum N, Dawson D, et al. What’s the evidence that NICE guidance has been implemented? Results from a national evaluation using time series analysis, audit of patients’ notes, and interviews. BMJ. 2004;329:999.

Flottorp SA, Oxman AD, Krause J, et al. A checklist for identifying determinants of practice: a systematic review and synthesis of frameworks and taxonomies of factors that prevent or enable improvements in healthcare professional practice. Implement Sci. 2013;8:1–11.

Davis DA, Taylor-Vaisey A. Translating guidelines into practice. A systematic review of theoretic concepts, practical experience and research evidence in the adoption of clinical practice guidelines. CMAJ. 1997;157:408–16.

Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8:1–74.

Jeffrey RA, To MJ, Hayduk-Costa G, Cameron A, Taylor C, Van Zoost C, Hayden JA. Interventions to improve adherence to cardiovascular disease guidelines: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:147.

McNamara RL, Chung SC, Jernberg T, et al. International comparisons of the management of patients with non-ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction in the United Kingdom, Sweden, and the United States: The MINAP/NICOR, SWEDEHEART/RIKS-HIA, and ACTION Registry-GWTG/NCDR registries. Int J Cardiol. 2014;175:240–7.

Hibbert PD, Hannaford NA, Hooper TD, et al. Assessing the appropriateness of prevention and management of venous thromboembolism in Australia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e008618.

Gagliardi AR, Marshall C, Huckson S, James R, Moore V. Developing a checklist for guideline implementation planning: review and synthesis of guideline development and implementation advice. Implement Sci. 2015;10:19.

Shaw B, Cheater F, Baker R, Gillies C, Hearnshaw H, Flottorp S, Robertson N. Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD005470.

Bernhardsson S, Larsson ME, Eggertsen R, Olsen MF, Johansson K, Nilsen P, Nordeman L, van Tulder M, Oberg B. Evaluation of a tailored, multi-component intervention for implementation of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines in primary care physical therapy. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:105.

Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, Jhonston M, Pitts N. Changing the behavior of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:107–12.

Davies P, Walker AE, Grimshaw JM. A systematic review of the use of theory in the design of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies and interpretation of the results of rigorous evaluations. Implement Sci. 2010;5:14.

Davis R, Campbell R, Hildon Z, Hobbs L, Michie S. Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: a scoping review. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9:323–44.

Sales A, Smith J, Curran G, Kochevar L. Models, strategies and tools: theory in implementing evidence-based findings into health care practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21 Suppl 2:S43–9.

Aakhus E, Granlund I, Odgaard-Jensen J, Oxman AD, Flottorp SA. A tailored intervention to implement guideline recommendations for elderly patients with depression in primary care: a pragmatic cluster randomised trial. Implement Sci. 2016;11:32.

Van Lieshout J, Huntink E, Koetsenruijter J, Wensing M. Tailored implementation of cardiovascular risk management in general practice: a cluster randomized trial. Implement Sci. 2016;11:115.

Albrecht L, Archibald M, Arseneau D, Scott SD. Development of a checklist to assess the quality of reporting of knowledge translation interventions using the Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) recommendations. Implement Sci. 2013;8:52.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Institute of Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10:53.

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6.

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, Proctor EK, Kirchner JE. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21.

Barlow T, Plant CE. Why we still perform arthroscopy in knee osteoarthritis: a multi-methods study. BMC Musculoskel Dis. 2015;16:85.

Phipps DL, Beatty PC, Parker D. Standard deviation? The role of perceived behavioural control in procedural violations. Safety Sci. 2015;72:66–74.

van Peet PG, Drewes YM, Gussekloo J, de Ruijter W. GPs’ perspectives on secondary cardiovascular prevention in older age: a focus group study in the Netherlands. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65:e739–47.

Vest BM, York TR, Sand J, Fox CH, Kahn LS. Chronic kidney disease guideline implementation in primary care: a qualitative report from the TRANSLATE CKD Study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28:624–31.

Chaves NJ, Cheng AC, Runnegar N, Kirschner J, Lee T, Buising K. Analysis of knowledge and attitude surveys to identify barriers and enablers of appropriate antimicrobial prescribing in three Australian tertiary hospitals. Intern Med J. 2014;44:568–74.

Murphy K, O’Connor DA, Browning CJ, French SD, Michie S, Francis JJ, et al. Understanding diagnosis and management of dementia and guideline implementation in general practice: a qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2014;9:31.

Ong BN, Morden A, Brooks L, Porcheret M, Edwards JJ, Sanders T, et al. Changing policy and practice: making sense of national guidelines for osteoarthritis. Soc Sci Med. 2014;106:101–9.

Porcheret M, Main C, Croft P, McKinley R, Hassell A, Dziedzic K. Development of a behaviour change intervention: a case study on the practical application of theory. Implement Sci. 2014;9:42.

Presseau J, Johnston M, Heponiemi T, Elovainio M, Francis JJ, Eccles MP, et al. Reflective and automatic processes in health care professional behaviour: a dual process model tested across multiple behaviours. Ann Behav Med. 2014;48:347–58.

Tavender EJ, Bosch M, Gruen RL, Green SE, Knott J, Francis JJ, et al. Understanding practice: the factors that influence management of mild traumatic brain injury in the emergency department-a qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2014;9:8.

Wilkinson SA, McCray S, Beckmann M, Parry A, McIntyre HD. Barriers and enablers to translating gestational diabetes guidelines into practice. Practical Diabetes. 2014;31:67–72.

Andrews AL, Teufel RJ, Basco Jr WT. Initiating inhaled steroid treatment for children with asthma in the emergency room: current reported prescribing rates and frequently cited barriers. Pediatr Emer Care. 2013;29:957–62.

Cheung JW, Rosenberg H, Vaillancourt C. Barriers and facilitators to intraosseous access in adult resuscitations when peripheral intravenous access is not achievable. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:250–6.

Duff J, Omari A, Middleton S, McInnes E, Walker K. Educational outreach visits to improve venous thromboembolism prevention in hospitalised medical patients: a prospective before-and-after intervention study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:398.

French SD, McKenzie JE, O'Connor DA, Grimshaw JM, Mortimer D, Francis JJ, et al. Evaluation of a theory-informed implementation intervention for the management of acute low back pain in general medical practice: the IMPLEMENT cluster randomised trial. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65471.

Guerrier M, Légaré F, Turcotte S, Labrecque M, Rivest LP. Shared decision making does not influence physicians against clinical practice guidelines. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62537.

Mazza D, Chapman A, Michie S. Barriers to the implementation of preconception care guidelines as perceived by general practitioners: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:36.

Schellart AJ, Zwerver F, Anema JR, Van der Beek AJ. Relationships between the intention to use guidelines, behaviour of insurance physicians and their determinants. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:400.

Teo CK, Baysari MT, Day RO. Understanding compliance to an antibiotic prescribing policy: perspectives of policymakers and prescribers. J Pharm Pract Res. 2013;43:32–6.

Cortoos PJ, Schreurs BH, Peetermans WE, De Witte K, Laekeman G. Divergent intentions to use antibiotic guidelines: a theory of planned behavior survey. Med Decis Making. 2012;32:145–53.

Islam R, Tinmouth AT, Francis JJ, Brehaut JC, Born J, Stockton C, et al. A cross-country comparison of intensive care physicians’ beliefs about their transfusion behaviour: a qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7:93.

Kramer L, Schlößler K, Träger S, Donner-Banzhoff N. Qualitative evaluation of a local coronary heart disease treatment pathway: practical implications and theoretical framework. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:36.

Rashidian A, Russell I. General practitioners’ intentions and prescribing for asthma: using the theory of planned behavior to explain guideline implementation. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:17–28.

Wahabi HA, Alziedan RA. Reasons behind non-adherence of healthcare practitioners to pediatric asthma guidelines in an emergency department in Saudi Arabia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:226.

Presseau J, Francis JJ, Campbell NC, Sniehotta FF. Goal conflict, goal facilitation, and health professionals’ provision of physical activity advice in primary care: an exploratory prospective study. Implement Sci. 2011;6:73.

Rashidian A, Russell I. Intentions and statins prescribing: can the theory of planned behaviour explain physician behaviour in following guideline recommendations? J Eval in Clin Pract. 2011;17:749–57.

van den Boogaard NM, van den Boogaard E, Bokslag A, van Zwieten MC, Hompes PG, Bhattacharya S, et al. Patients’ and professionals’ barriers and facilitators of tailored expectant management in subfertile couples with a good prognosis of a natural conception. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2122–8.

Zwerver F, Schellart AJ, Anema JR, Rammeloo KC, van der Beek AJ. Intervention mapping for the development of a strategy to implement the insurance medicine guidelines for depression. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:9.

Askelson NM, Campo S, Lowe JB, Dennis LK, Smith S, Andsager J. Factors related to physicians’ willingness to vaccinate girls against HPV: the importance of subjective norms and perceived behavioral control. Women Health. 2010;50:144–58.

Bekkers MJ, Simpson SA, Dunstan F, Hood K, Hare M, Evans J, et al. Enhancing the quality of antibiotic prescribing in primary care: qualitative evaluation of a blended learning intervention. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:34.

Van Den Boogaard E, Hermens RP, Leschot NJ, Baron R, Vollebergh JH, Bernardus RE, et al. Identification of barriers for good adherence to a guideline on recurrent miscarriage. Acta Obstet Gyn Scan. 2011;90:186–91.

Waddimba AC, Meterko M, Beckman HB, Young GJ, Burgess JF. Provider attitudes associated with adherence to evidence-based clinical guidelines in a managed care setting. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;67:93–116.

Bartholomew LK, Cushman WC, Cutler JA, Davis BR, Dawson G, Einhorn PT, et al. Getting clinical trial results into practice: design, implementation, and process evaluation of the ALLHAT Dissemination Project. Clin Trials. 2009;6:329–43.

Rashidian A, Eccles MP, Russell I. Falling on stony ground? A qualitative study of implementation of clinical guidelines’ prescribing recommendations in primary care. Health Policy. 2008;85:148–61.

Vogt F, Hall S, Hankins M, Marteau TM. Evaluating three theory-based interventions to increase physicians’ recommendations of smoking cessation services. Health Psychol. 2009;28:174–82.

Althabe F, Buekens P, Bergel E, Belizán JM, Campbell MK, Moss N, et al. A behavioral intervention to improve obstetrical care. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1929–40.

Green H, Johnston O, Cabrini S, Fornai G, Kendrick T. General practitioner attitudes towards referral of eating-disordered patients: a vignette study based on the theory of planned behaviour. Ment Health Fam Med. 2008;5:213–8.

McGinty J, Anderson G. Predictors of physician compliance with American Heart Association guidelines for acute myocardial infarction. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2008;31:161–72.

Griffiths C, Sturdy P, Brewin P, Bothamley G, Eldridge S, Martineau A, et al. Educational outreach to promote screening for tuberculosis in primary care: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:1528–34.

Luxford K, Hill D, Bell R. Promoting the implementation of best-practice guidelines using a matrix tool. Dis Manage Health Outcomes. 2006;14:85–90.

Rebergen D, Hoenen J, Heinemans A, Bruinvels D, Bakker A, van Mechelen W. Adherence to mental health guidelines by Dutch occupational physicians. Occup Med. 2006;56:461–8.

Reyna VF, Lloyd FJ. Physician decision making and cardiac risk: effects of knowledge, risk perception, risk tolerance, and fuzzy processing. J Exp Psychol-Appl. 2006;12:179–95.

Gagliardi AR, Alhabib S, Members of the Guidelines International Network Implementation Working Group. Trends in guideline implementation: a scoping systematic review. Implement Sci. 2015;10:54.

Fleuren MA, Paulussen TG, Van Dommelen P, Van Buuren S. Towards a measurement instrument for determinants of innovations. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26:501–10.

Breuer E, Lee L, De Silva M, Lund C. Using theory of change to design and evaluate public health interventions: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2016;11:63.

Watkins K, Wood H, Schneider CR, Clifford R. Effectiveness of implementation strategies for clinical guidelines to community pharmacy: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2015;10:151.

Scott SD, Albrecht L, O’Leary K, Ball GDC, Hartling L, Hofmeyer A, et al. Systematic review of knowledge translation strategies in the allied health professions. Implement Sci. 2012;7:70.

Hoffman TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687.

Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G. Intervention mapping: a process for developing theory- and evidence-based health education programs. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25:545–63.

Fernandez ME, Gonzales A, Tortolero-Luna G, Partida S, Bartholomew LK. Using intervention mapping to develop a breast and cervical cancer screening program for Hispanic farm workers. Health Promot Pract. 2005;6:394–404.

Jager C, Steinhauser J, Freund T, Baker R, Agarwal S, Godycki-Cwirko M, et al. Process evaluation of five tailored programs to improve the implementation of evidence-based recommendations for chronic conditions in primary care. Implement Sci. 2016;11:123.

Nilsen P, Bernhardsson S. Towards evidence-based physiotherapy—research challenges and needs. J Physiother. 2013;59:143–4.

Squires JE, Sullivan K, Eccles MP, Worswick J, Grimshaw JM. Are multifaceted interventions more effective than single component interventions in changing healthcare professionals’ behaviours? An overview of systematic reviews. Implement Sci. 2014;9:152.

Suman A, Dikkers MF, Schaafsma FG, van Tulder MW, Anema JR. Effectiveness of multifaceted implementation strategies for the implementation of back and neck pain guidelines in health care: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2016;11:126.

Manojlovich M, Squires JE, Davies B, Graham ID. Hiding in plain site: communication theory in implementation science. Implement Sci. 2015;10:58.

Thomas A, Menon A, Boruff J, Rodriguez AM, Ahmed S. Applications of social constructivist learning theories in knowledge translation for healthcare professionals: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2014;9:54.

Attieh R, Gagnon MP, Estabrooks CA, Légaré F, Ouimet M, Roch G, Ghandour el K, Grimshaw J. Organizational readiness for knowledge translation in chronic care: a review of theoretical components. Implement Sci. 2013;8:138.

Oborn E, Barrett M, Racko G. Knowledge translation in healthcare: incorporating theories of learning and knowledge from the management literature. J Health Organ Manag. 2013;27:412–31.

Acknowledgements

Members of the Guidelines International Network Implementation Working Group (g-i-n.net/working-groups/implementation) reviewed this manuscript to further refine the interpretation of findings and enhance communication of the findings. They included:

Samia Alhabib, Department of Family Medicine, King Abdullah Bin Abdulaziz University Hospital, Saudi Arabia

Margot Fleuren, Organisation for Applied Scientific Research TNO, The Netherlands

Margie Fortino, Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals, United States

Danielle Mazza, Monash University, Australia

Niamh O’Rourke, Clinical Effectiveness Unit, Department of Health, Ireland

Melina Willson, Systematic Reviews and Health Technology Assessments, NHMRC Clinical Trials Centre, University of Sydney, Australia

The Guidelines International Network (G-I-N; www.g-i-n.net) is a Scottish Charity (SC034047). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and G-I-N is not liable for any use that may be made of the information presented.

Funding

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Authors’ contributions

ARG envisioned and planned the study and provided funding for research assistant support. All authors established study objectives, collected and analyzed or interpreted data, drafted the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

MEDLINE search strategy. (DOCX 31 kb)

Additional file 2:

Characteristics of included studies. (DOC 127 kb)

Additional file 3:

Description of interventions evaluated in included studies. (DOC 58 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, L., Bernhardsson, S., Vernooij, R.W.M. et al. Use of theory to plan or evaluate guideline implementation among physicians: a scoping review. Implementation Sci 12, 26 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0557-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0557-0