Abstract

This study aimed to identify critical risk factors for childhood malnutrition and inform targeted interventions. Childhood malnutrition remains a pressing concern in the coastal regions of Bangladesh. Data were extracted from the latest Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2017–2018 and children aged 0–59 months and their mothers aged 15–49 years from 17 coastal districts were included as study population in this study. We performed multivariable logistic regression model to determine the risk factors and a total 2153 children were eligible for the analysis. Stunting, wasting and underweight prevalence was 31.4%, 8.5% and 21.1% respectively. Stunting was more common in children aged 24–35 months with compared to their younger counterparts [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 3.32, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.35–4.67]. Children to mothers with higher education exhibited 69% (AOR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.18–0.52) lower risk of stunting compared to those with no education. Similarly, children in poorest and poorer households had 2.2 and 1.83 times higher odds of stunting respectively than those in the richest households. Children born to obese mothers (compared to normal) were 34% less likely to be stunted (AOR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.51–0.85). Children who had fever and underweight mothers reported wasting. Increasing child age, low maternal education, poorest wealth index, unimproved toilet facilities and childhood morbidity were identified as significant risk factors for underweight. Results support the requirement of effective and appropriate interventions for this particular region considering the identified risk factors to reduce childhood malnutrition in Bangladesh.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Malnutrition is a condition that stems from undernutrition of individuals, inadequate access to essential nutrients including protein-energy, micronutrients like iron, zinc, vitamin A and iodine [1]. The prevalence of childhood undernutrition is considered a complex global problem and the prevalence is highest in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) [2]. Globally, 149 and 45 million under 5 children were estimated by the World Health Organization as stunted and wasted respectively and about 45% in deaths of this age group are linked to undernutrition which mostly occur in LMICs [3]. Asian countries bear a significant portion of globally undernourished children in which 53% showed signs of stunting and 70% showed signs of wasting in 2020 [4]. Although Bangladesh has progressed significantly in combating childhood undernutrition during the past few decades, it continues as a serious public health issue of the country due to socioeconomic, demographic and environmental factors that contribute to the morbidity and mortality of under 5 children [5]. The socio-economic characteristics of a community, including gender inequity, educational background, and poverty [6] significantly determine health and nutritional outcomes affecting the prevalence and incidence of malnutrition at both the community and household levels [7].

Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics and inappropriate infant and young child-feeding practices have been identified as primary contributing factors to malnutrition for children under five years of age [5, 8,9,10]. In Bangladesh, socio-economic condition of households emerged as a critical determining factor of childhood malnutrition where children from households with comparatively higher socioeconomic status are less likely to be underweight [5, 11]. In addition to these, poor access to drinking water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities is another key factor for child undernutrition [12] driving to morbidities like diarrhoea that also increase the risk of undernutrition in child undernutrition [13]. Several previous studies conducted in Bangladesh reported that inadequate WASH facilities or poor hygiene practice increased child malnutrition at household level [14,15,16].

It is evident through several studies that undernutrition prevalence and socio-economic factors in developing countries vary by geographic area [17,18,19] and environmental conditions like topography and climate. Numerous studies highlighted that the reduction of agrobiodiversity adversely affected food accessibility leading to a decline in consumption of variety of nutritious foods among communities residing in saline-prone coastal region of Bangladesh [20]. Bangladesh, a country of South Asia is highly susceptible to numerous natural disasters [21]. Particularly, the coastal part of the country are considered as the zone of multiple vulnerabilities [22]. Among the 35 million people in the coastal regions in Bangladesh more than 30% are under-resourced [23] with comparatively lower coverage of WASH facilities (25.2% in central coastal zone) than mainland [24]. Weaker social network, lack of access to WASH facilities exacerbated by the rising frequency and severity of natural disasters attributed to climate change, climate variability and poor access to health facilities [25] are the prime factors for the higher vulnerability of coastal households [26]. Climate change adaptation and resilience projects in coastal Bangladesh failed to demonstrate their intended outcomes due to limited resources of coastal communities [27] along with inadequate government initiatives, follow-up procedures, and a highly centralised organizational structure [28].

Numerous studies have explored influencing factors such as climate change [29,30,31], socioeconomic inequalities [32] and child feeding practices and household food insecurity [33] of child malnutrition while water and sanitation facilities of child morbidities [34, 35] in specific zone (eastern or central or western) of the coastal region of Bangladesh. Despite the vulnerability of coastal households, no study has been conducted on socio-economic inequalities and poor sanitation associated with child malnutrition critically focused on diverse coastal regions of Bangladesh. Consequently, it is imperative to better understand the prevalence and distribution of households experiencing poor sanitation and the associations between these socio-economic conditions and childhood malnutrition. The primary hypothesis of the study was, childhood malnutrition is directly or indirectly associated with the socio-economic characteristics and sanitation facilities of the households in the coastal region of Bangladesh. This study aimed to understand the association between socio-economic characteristics, available sanitation facilities and childhood malnutrition in the coastal regions of Bangladesh.

2 Methods

2.1 Study site

A total of 17 coastal districts; five from Barisal division, six from each of the Khulna and Chattogram division were considered as the sites for this study (Fig. 1).

2.2 Data source

In this study, we used the latest data of Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2017–2018 (BDHS’ 2018), which is a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. We extracted the data for 17 coastal districts from geospatial covariates dataset of BDHS using geographical coordinates for the population of interest for this study. Data for selected districts were extracted using shapefiles provided in the dataset to identify and select specific districts based on their geographic boundaries. These comprised ever-married women (15–49 years old) and their children (0–59 months old) from 17 coastal districts from three coastal divisions. The BDHS’18 survey is based on a two-stage stratified sample where 675 enumeration areas (EAs), 250 from the urban and 425 from the rural area were selected in the first stage with probability proportional to EA size. In the next stage, on average 30 households from each EA were selected through systematic sampling which led to 20,250 households. For the present study, a total of 2153 households were selected where data were collected in a form of household survey using a structured questionnaire.

2.3 Outcome measures

As the outcome variable child malnutrition indices were considered for our study. In BDHS 2018, child malnutrition was measured by standard anthropometric indicators of height-for age Z-score (HAZ), weight-for-age Z-score (WAZ) and weight-for-height Z-score (WHZ) as defined by the WHO [36]. Child’s height-for-age represents their linear growth and weight-for-height explains their nutritional status. Another indicator weight-for-age is a combined measure of height-for age and weight-for-height. Thus, stunting, wasting and underweight were measured as the outcome of interest and specified as being less than -2 standard deviation (< -2SD) less than the median value for HAZ, WHZ and WAZ respectively.

2.4 Exposure and covariates

Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics including age group of the children, children sex, place of residence, educational attainment of caregivers, wealth index of the households were considered as the major exposure variables for the study. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to compute households’ wealth index [37] on the basis of number and types of consumer goods a household own (ownership of agricultural land and farm animals, radio, television, mobile phone, electric fan, almirah/wardrobe, refrigerator, water pump, computer, DVD/VCD player, air conditioner and IPS/generator), means of transportation (car or bicycle) and household characteristics (drinking water source, types of toilet facilities, roof materials, wall materials, flooring materials and number of sleeping rooms). Households’ wealth index is a combined measurement of a household’s cumulative living standard, was separated into five categories (i.e., poorest, poorer, middle, richer and richest) using PCA by DHS program. At first a wealth score was calculated based on the information of household characteristics by PCA and then divided the households into five equal quintiles accordingly. Drinking water source and types of toilet facilities were also considered as another exposure for the outcome variables. Piped into dwelling, tube well/borehole, piped to yard/plot and neighbour, standpipe/public tap, protected well, rainwater, bottled water and cart with small tank were categorised as improved sources of drinking water. While river, dam, lake, canal, ponds, irrigation channel, stream and unprotected well were considered as unimproved sources of drinking water. Pit latrine with slab, flush to piped sewer system, to pit latrine, to septic tank and ventilated improved pit latrine were categorised as improved toilet facilities whereas, unimproved toilet facilities included no facility/bush/field, hanging toilet (made up of structures with bamboo and corrugated metal that were hung above the ground on poles letting waste drop straight down into a soup of mud and trash below), pit latrine without slab/open pit and flush to somewhere else or not known. Child breastfeeding practice and morbidity status (children who had diarrhoea, fever and cough in the two weeks prior to the survey) was considered as covariates for this study. Body mass index (BMI) of the caregivers was also considered as a covariate and was measured as weight in kg divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2). Caregiver’s BMI was categorized into four groups as underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–22.9 kg/m2), overweight (23–24.9 kg/m2) and obese (≥ 25 kg/m2) according to the Asia–Pacific cut-off points [38].

2.5 Statistical analysis

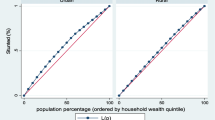

Data analysis included descriptions of the study population and estimation of the status of household socio-economic characteristics, sanitation facilities, child nutritional outcomes and morbidity and maternal BMI were presented with frequencies, percentages and proportion with respective 95% confidence interval (CI) using a binomial exact method. Cross tabulation with Chi square (χ2) test was used to determine the prevalence/percentage and associations (p values in χ2 test) between the selected exposures or covariates and outcomes. Univariate logistic regression was performed and variables for multivariable logistic regression model were adjusted setting the significance level at p < 0.25 in the univariate logistic regression to assess the statistical associations of child malnutrition, sociodemographic and sanitation facilities status or other covariates and presented in adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with a 95% CI [39]. All the significant variables in univariate logistic regression were selected for multivariable logistic regression model because no multicollinearity among the independent variables were found. Model fits of the multivariable logistic regression model were assessed using Pearson χ2 (goodness-of-fit test) and Hosmer and Lemeshow’s goodness-of-fit test. In Hosmer and Lemeshow’s goodness-of-fit test we determined p-values for first, second and third model as 0.96, 0.73 and 0.32, which was 0.19, 0.06 and 0.27, in Pearson χ2 (goodness-of-fit test). Thus, non-significant p-values (> 0.05) suggest good fit of the model. Sampling weights were applied to ensure that the results are accurately represented at the division and national levels. In all regression models, missing data were handled using listwise deletion method and total observations used in three models were 2014 for stunting, 2033 for wasting and 2084 for underweight. Whole analysis was performed by the STATA, a statistical software package version 17 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics

Description of the socio-economic and household sanitation facilities status, prevalence of child malnutrition, child morbidity status and maternal BMI have been presented in Table 1. The highest (22.8%) and lowest (17.5%) proportion of children belonged to the age group of 0–11 and 36–47 months respectively. Majority of the households (72.5%, n = 1324) were located in rural areas, and most of the household heads (84.7%) were male. Of the mothers over half (52.5%) had secondary level of education. In terms of wealth index distribution, it was found that the highest proportion (21.3%) of the households were from the poorest group followed by richest (20.9%), middle (19.9%), richer (19.1%) and poorer (18.8%). The study revealed that, majority of the households (96.4%) had access to an improved drinking water source while a notable portion (35.3%) of the households had unimproved toilet facilities (Table 1).

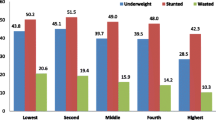

Stunting, wasting and underweight prevalence among the children in the coastal regions of Bangladesh was 31.4%, 8.5% and 21.1%, respectively. A substantial portion of the children were suffering from fever (30.5%) and cough (33.4%) while a small portion of the children (5.6%) were found to suffer from diarrhoea. In case of caregivers’ nutritional status maximum proportion (42%) had normal BMI which was followed by obese (30.2%), overweight (15.8%) and underweight (12%) (Table 1).

3.2 Association of child malnutrition with socio-economic variabilities, sanitation facilities, child morbidities and maternal BMI

Table 2 described that statistically higher significant prevalence of stunting was found among children aged 24–35 months (41.9%; χ2= 56, p < 0.001), from rural areas (33.7%; χ2 = 17.37, p < 0.001), born to mothers with no formal education (45.8%; χ2 = 88.02, p < 0.001), from poorest households (44.9%; χ2 = 96.82, p < 0.001), having unimproved toilets (37.4%; χ2 = 26.48, p < 0.001) and born to mothers with underweight to normal BMI (35.3% to 35.6%; χ2 = 33.94, p < 0.001). The wasting prevalence was found significantly higher for the children from poorest households (12.4%; χ2 = 14.31, p < 0.005), had fever (10.5%; χ2 = 5.89, p < 0.005), practicing breastfeeding (9.3%; χ2 = 3.95, p < 0.005) and children born to underweight mothers (14.8%; χ2 = 20.42, p < 0.001). Furthermore, significantly higher prevalence of underweight was found with children aged 48–59 months (25.7%; χ2 = 19.89, p < 0.005), born to mothers with no formal education (38.9%; χ2 = 60.76, p < 0.001), from poorest households (31.3%; χ2 = 53.32, p < 0.001), having unimproved toilet facilities (27.4%; χ2 = 30.32, p < 0.001), suffered from fever (26%; χ2 = 15.30, p < 0.001) and low maternal BMI (29.3%; χ2 = 34.65, p < 0.001).

3.3 Factors associated with child malnutrition

All significant variables of the univariate logistic regression model (Supplementary Table S1) were considered for the multivariable logistic regression model. Children who belong to the age group 12–23 months had 2.24 times higher odds (AOR = 2.24, 95% CI: 1.63–3.07) of stunting compared to the children age group 0–11 months. The odds was also found higher for the children belong to the age group 24–35 (AOR = 3.32, 95% CI: 2.35–4.67), 36–47 (AOR = 2.35, 95% CI: 1.56–3.55) and 48–59 (AOR = 1.97, 95% CI: 1.32–2.95) compared to the children age group 0–11 months. Mothers having higher education were 69% (AOR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.18–0.52) less likely to have stunted children compared to the mothers having no education. We also found that, children from poorest households showed higher likelihood of being stunted (AOR = 2.20, 95% CI: 1.48–3.25) followed by children from poorer households (AOR = 1.83, 95% CI: 1.24–2.70) compared to the children from richest households. Children born to mothers who are obese (compared with their normal BMI) were 34% less likely of being stunted (AOR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.51–0.85) (Table 3).

Children who had fever showed 1.51 times higher odds (AOR = 1.51, 95% CI: 1.08–2.11) of being wasted when compared with the children who had no fever. Furthermore, children of the underweight mothers also showed 1.94 times higher odds (AOR = 1.94, 95% CI: 1.26–3.00) compared to children born to mothers with normal BMI (Table 3).

Children belonging age group 24–35 months had 1.75 times higher odds (AOR = 1.75, 95% CI: 1.24–2.47) which is almost similar (AOR = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.21–2.48) to the age group 36–47 months compared to the children of 0–11 months. However, the odds of being underweight was quite higher (AOR = 2.14, 95% CI: 1.52–3.03) for the children who belong to the age group 48–59 months compared to the children age group 0–11 months. The odds of being underweight also decreases with increasing mother’s educational level. Children from poorest households were 57% (AOR = 1.57, 95% CI: 1.02–2.42) more at odds of underweight compared with children from richest households. Children from households having unimproved toilet facilities 29% (AOR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.01–1.65) more likely to be underweight compared to those having improved toilet facilities. Significance association was found for co-morbidity such as fever (AOR = 1.68, 95% CI: 1.27–2.21) with underweight.

Furthermore, children to the overweight mothers were 32% (AOR = 0.68, 95% CI 0.48–0.96) and obese mothers were 39% (AOR = 0.61, 95% CI 0.45–0.81) less likely to be underweight compared to the mothers having normal BMI (Table 3).

4 Discussion

Findings of our study revealed significance associations between child malnutrition, socioeconomic inequalities and unimproved toilet facilities. Childrens’ age, low maternal education, lower household wealth index, unimproved toilet facilities, child morbidity and maternal BMI were found as significant risk factors for child malnutrition. We also found that one-fifth of the households were in the poorest wealth index and more than one third had unimproved toilet facilities in the coastal region of Bangladesh. Previous studies also reported that majority of the households in the coastal region of the country have vulnerable livelihoods [40] and lower socioeconomic status, unhygienic toilet facility have significant associations with child malnutrition [41, 42].

Findings of the study showed that sociodemographic factors including age of children and mother’s educational level are significant predictors for child undernutrition (stunting and underweight) in the coastal regions of Bangladesh. Prevalence of stunting and underweight was significantly higher among older age group, with the highest prevalence occurring in the age group 24–35 months. This trend may be the effects of inappropriate initiation of complementary feeding with inadequate diversity in diet and lack of nutritional knowledge of their caregivers [43, 44]. Additionally the way of complementary feeding practiced by the caregivers of the younger children in Bangladesh is still found to be deteriorating [45]. Public health interventions should prioritize educating caregivers about proper feeding practices for infants and young children, emphasizing the importance of dietary diversity and timely initiation of complementary feeding.

It was also observed that mother’s educational level had protective effect on stunting and underweight which is often regarded as a critical factor for child’s nourishment [46, 47] because this corresponds to women’s knowledge regarding mothering and subsequent care-taking of under 5 children [48]. A previous study reported that mothers having formal education have knowledge on child health and nutrition and are capable of identifying illness and subsequent treatment for their children while, mothers having no formal or lower education usually don’t know about quality foods, healthy and hygienic living conditions which could have an impact on their children’s health and nutritional status as well as their own [18]. Therefore, it is necessary to arrange community nutrition and public health intervention programmes on a regular basis to ensure proper health practices including exclusive breast feeding up to six months and timely initiation of colostrum feeding appropriately in the coastal regions of Bangladesh [49].

Household wealth index was also identified as a significant risk factor for child stunting and underweight. Children living in the households with the poorest wealth index were more likely to be stunted because households with lower socioeconomic status might have less resources to access nutritious food for their children [50]. It is well established by several previous studies both globally and in the Bangladesh context that socio-economic inequality is a significant predictor of child health and well-being [41, 51, 52] which is in concordance with the findings of our study.

Unimproved toilet facility and child morbidity were other significant risk factors for child undernutrition in this study. Previous studies identified negative impacts of unimproved toilet facility as well as poor sanitation facilities on both child morbidity and their nutritional status [53, 54]. Children exposed to unhygienic environments resulting from household inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene facilities faced increased risks of morbidities due to heightened exposure to infectious diseases [55, 56]. Consequently, childhood morbidities play a significant role in their nutritional status and it is evidence indicated that children with different morbidities such as diarrhoea, fever, and acute respiratory infection have more likelihood of being underweight than those having no morbidities [57].

Maternal BMI was observed as a significant predictor for child malnutrition in this study where obesity of mothers was found as a protective factor for stunting and underweight. As mother’s BMI represents her own physical attributes, stature and nourishment [50] so, it is not surprising that maternal BMI is a significant determinant for child undernutrition. In this study, low maternal BMI of mothers was identified as significant risk factor for child wasting because malnourished mother cannot provide sufficient breast-milk due to their nutritional deficiency [10].

Households with lower socio-economic status cannot afford adequate food which may leads to greater risk of maternal undernutrition as well as child undernutrition. Childhood malnutrition is significantly correlated with household’s socio-economic inequalities [58] as wealthier households have access and can manage to pay for additional healthy and nutritious food [59]. Policy makers should develop and implement research based initiatives to improve nutrition education and behaviours of adults for health promotion specially targeting low socioeconomic groups [60] in the coastal region of Bangladesh. Findings of the study supported our initial hypothesis revealing that childhood malnutrition is directly associated with socioeconomic characteristics and sanitation facilities of the households in the coastal region of Bangladesh. Therefore, addressing socioeconomic inequalities through targeted interventions, social safety nets, poverty alleviation programs, ensuring social protection and improving living condition should be a priority in efforts to combat childhood malnutrition in these particular regions.

4.1 Strengths and limitations of the study

Our study is strengthened by inclusion of the broad range of critical key factors of childhood malnutrition and its unique focus on extensive coastal regions of Bangladesh, where communities face distinct challenges. However, this study has several limitations. The study is cross-sectional, which limits our ability to prove a causal relationship between exposures with key nutritional outcomes. Recall bias on responding childhood morbidity and household socio-economic status among the respondents may also be a limitation of this study. Among 19 coastal districts we extracted the data of 17 districts from three coastal divisions where there may be some study participants who are not exclusively exposed to the coastal influence. Furthermore, the data did not include the critical influencing indicator of malnutrition like household food insecurity status.

5 Conclusion

This study shows that the sociodemographic conditions and sanitation facilities status are key determinants of child malnutrition in the coastal region of Bangladesh. This region is highly susceptible to child malnutrition. Given the geographical vulnerabilities of the coastal area compared to the mainland, policymakers should prioritize the development of targeted and sustainable interventions. To reduce childhood malnutrition in this region further research addressing other critical influencing factors like household food insecurity and climate change needs to be incorporated. Additionally, longitudinal research should be designed along with a cross-sectional setting to get a clear snapshot of the situation and understand the dynamic interaction of the determining factors associated with child malnutrition. Addressing these research gaps through further research will enable to formulate of more precise, holistic and sustainable policies to consistently reduce child malnutrition in the coastal regions of Bangladesh.

Data availability

Data is available in the Bangladesh demographic and health survey website.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Jiang W, Li X, Wang R, Du Y, Zhou W. Cross-country health inequalities of four common nutritional deficiencies among children, 1990 to 2019: data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-17942-y.

Wali N, Agho K, Renzaho A. Past drivers of and priorities for child undernutrition in South Asia: a mixed methods systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):1–8.

WHO. Fact sheets: malnutrition. World Health Organization; 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition.

WHO: Levels and trends in child malnutrition: UNICEF. 2021.

Das S, Gulshan J. Different forms of malnutrition among under five children in Bangladesh: a cross sectional study on prevalence and determinants. Bmc Nutrition. 2017;3(1):1–12.

Asim M, Nawaz Y. Child malnutrition in Pakistan: evidence from literature. Children. 2018;5(5):60.

Emamian, Hassan M, Gorgani N, Fateh M. Malnutrition status in children of Shahroud, Iran. 2011;6(1):7–14. https://sid.ir/paper/108097/en.

Bairagi R, Chowdhury MK. Socioeconomic and anthropometric status, and mortality of young children in rural Bangladesh. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23(6):1179–84.

Faruque ASG, Ahmed AS, Ahmed T, Islam MM, Hossain MI, Roy S, Alam N, Kabir I, Sack DA. Nutrition: basis for healthy children and mothers in Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26(3):325.

Rayhan MI, Khan MSH. Factors causing malnutrition among under five children in Bangladesh. Pak J Nutr. 2006;5(6):558–62.

Devkota S, Panda B. Socioeconomic gradients in early childhood health: evidence from Bangladesh and Nepal. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):1–16.

Cumming O, Cairncross S. Can water, sanitation and hygiene help eliminate stunting? Current evidence and policy implications. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12:91–105.

Richardson L, Dutton P. Nutrition-WASH Toolkit: guide for practical joint actions nutrition-water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH). In 2016.

Ghosh S, Kabir MR, Islam M, Bin Shadat Z, Ishat FS, Hasan R, Hossain I, Alam SS, Halima O. Association between water, sanitation, and hygiene practices (WASH) and anthropometric nutritional status among selected under-five children in rural Noakhali, Bangladesh: a cross-sectional analysis. J Water Sanitation Hyg Dev. 2021;11(1):141–51.

Hasan MM, Al Asif CA, Barua A, Banerjee A, Kalam MA, Kader A, Wahed T, Noman MW, Talukder A. Association of access to water, sanitation and handwashing facilities with undernutrition of children below 5 years of age in Bangladesh: evidence from two population-based, nationally representative surveys. BMJ Open. 2023;13(6): e065330.

Mostafa I, Naila NN, Mahfuz M, Roy M, Faruque AS, Ahmed T. Children living in the slums of Bangladesh face risks from unsafe food and water and stunted growth is common. Acta Paediatr. 2018;107(7):1230–9.

Hong R, Banta JE, Betancourt JA. Relationship between household wealth inequality and chronic childhood under-nutrition in Bangladesh. Int J Equity Health. 2006;5(1):1–10.

Mia MN, Rahman MS, Roy PK. Sociodemographic and geographical inequalities in under-and overnutrition among children and mothers in Bangladesh: a spatial modelling approach to a nationally representative survey. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(13):2471–81.

Srinivasan CS, Zanello G, Shankar B. Rural-urban disparities in child nutrition in Bangladesh and Nepal. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1–15.

Mazumder T, Rutherford S, Rahman SM, Talukder MR. Nutritional status of a young adult population in saline-prone coastal Bangladesh. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1095223.

Haque A, Jahan S. Regional impact of cyclone sidr in Bangladesh: a multi-sector analysis. Int J Disaster Risk Sci. 2016;7(3):312–27.

Mallick B, Rahaman KR, Vogt J. Social vulnerability analysis for sustainable disaster mitigation planning in coastal Bangladesh. Disaster Prev Manag Int J. 2011;20(3):220–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/09653561111141682.

BBS. Household Income and Expenditure Survey—2010. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Planning, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh; 2011. https://203.112.218.65:8008/WebTestApplication/userfiles/Image/LatestReports/HIES-10.pdf.

Ahmed MS, Islam MI, Das MC, Khan A, Yunus FM. Mapping and situation analysis of basic WASH facilities at households in Bangladesh: evidence from a nationally representative survey. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(11): e0259635.

Rafa N, Jubayer A, Uddin SMN. Impact of cyclone Amphan on the water, sanitation, hygiene, and health (WASH2) facilities of coastal Bangladesh. J Water Sanit Hyg Dev. 2021;11(2):304–13.

Toufique KA, Yunus M. Vulnerability of livelihoods in the coastal districts of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Dev Stud. 2013;36(1):95–120. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41968864.

Tasnuva A, Hossain MR, Salam R, Islam ARMT, Patwary MM, Ibrahim SM. Employing social vulnerability index to assess household social vulnerability of natural hazards: an evidence from southwest coastal Bangladesh. Environ Dev Sustain. 2021;23:10223–45.

Haque MA, Rahman D, Rahman MH. The importance of community based approach to reduce sea level rise vulnerability and enhance resilience capacity in the coastal areas of Bangladesh: a review. 2016. http://umt-ir.umt.edu.my:8080/handle/123456789/6965.

Ashrafuzzaman M, Gomes C, Guerra J. The changing climate is changing safe drinking water, impacting health: a case in the southwestern coastal region of Bangladesh (SWCRB). Climate. 2023;11(7):146.

Hanifi SMA, Menon N, Quisumbing A. The impact of climate change on children’s nutritional status in coastal Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med. 2022;294: 114704.

Wolfle A, Channon AA. The effect of the local environment on child nutritional outcomes: how does seasonality relate to wasting amongst children under 5 in south-west coastal Bangladesh? Popul Environ. 2023;45(3):22.

Hasan MM, Uddin J, Pulok MH, Zaman N, Hajizadeh M. Socioeconomic inequalities in child malnutrition in Bangladesh: do they differ by region? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):1079.

Al Mamun MA, Saha S, Li J, Binta A Ghani R, Al Hasan SM, Begum A. Child feeding practices of childbearing mothers and their household food insecurity in a coastal region of Bangladesh. INQUIRY J Health Care Org Provision Financing 2022, 59:00469580221096277.

Asma KM, Kotani K. Salinity and water-related disease risk in coastal Bangladesh. EcoHealth. 2021;18(1):61–75.

Kikuchi M. Influence of sanitation facilities on diarrhea prevalence among children aged below 5 years in flood-prone areas of Bangladesh: a multilevel analysis. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2023;30(43):97925–35.

Wali N. WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: methods and development: World Health Organization; 2006.

Dhaka B. National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), and ICF Mitra and Associates, ICF international. Bangladesh Demograph Health Surv. 2017; 18.

Pan W-H, Yeh W-T. How to define obesity? Evidence-based multiple action points for public awareness, screening, and treatment: an extension of Asian-Pacific recommendations. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17(3):370.

Hosmer DW LS. Applied logistic regression. In: Wiley, New York: Wiley Online Library; 1991: 82–133.

Mudasser M, Hossain MZ, Rahaman KR, Ha-Mim NM. Investigating the climate-induced livelihood vulnerability index in coastal areas of Bangladesh. World. 2020;1(2):12.

Mahumud RA, Alam K, Renzaho AM, Sarker AR, Sultana M, Sheikh N, Rawal LB, Gow J. Changes in inequality of childhood morbidity in Bangladesh 1993–2014: a decomposition analysis. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(6): e0218515.

Rahman A, Chowdhury S, Karim A, Ahmed S. Factors associated with nutritional status of children in Bangladesh: a multivariate analysis. Demography India. 2008;37(1):95–109.

Ahmed AS, Ahmed T, Roy S, Alam N, Hossain MI. Determinants of undernutrition in children under 2 years of age from rural Bangladesh. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:821–4.

Menon P, Bamezai A, Subandoro A, Ayoya MA, Aguayo VM. Age-appropriate infant and young child feeding practices are associated with child nutrition in India: insights from nationally representative data. Matern Child Nutr. 2015;11(1):73–87.

Na M, Aguayo VM, Arimond M, Narayan A, Stewart CP. Stagnating trends in complementary feeding practices in Bangladesh: an analysis of national surveys from 2004–2014. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14: e12624.

Hasan MT, Soares Magalhaes RJ, Williams GM, Mamun AA. The role of maternal education in the 15-year trajectory of malnutrition in children under 5 years of age in Bangladesh. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12(4):929–39.

Vollmer S, Bommer C, Krishna A, Harttgen K, Subramanian S. The association of parental education with childhood undernutrition in low-and middle-income countries: comparing the role of paternal and maternal education. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):312–23.

Mansur M, Afiaz A, Hossain MS. Sociodemographic risk factors of under-five stunting in Bangladesh: assessing the role of interactions using a machine learning method. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(8): e0256729.

Roy RK, Matubbar MS, Kamruzzaman M, Ud-Daula A. Determination of nutritional status of under-five year children employing multiple interrelated contributing factors in southern part of Bangladesh. Int J Nutr Food Sci. 2015;4(3):264–72.

Kumar P, Rashmi R, Muhammad T, Srivastava S. Factors contributing to the reduction in childhood stunting in Bangladesh: a pooled data analysis from the Bangladesh demographic and health surveys of 2004 and 2017–18. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1–14.

Cabieses B, Pickett KE, Wilkinson RG. The impact of socioeconomic inequality on children’s health and well-being. The Oxford handbook of economics and human biology. 2016:244–265.

Van de Poel E, O’Donnell O, Van Doorslaer E. Are urban children really healthier? Evidence from 47 developing countries. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(10):1986–2003.

Islam MARM, Uddin MF, Tariqujjaman M, Karmakar G, Rahman MA, Kelly M, Gray D, Ahmed T, Sarma H. Household food insecurity and unimproved toilet facilities associate with child morbidity: evidence from a cross-sectional study in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13469-2.

Torlesse H, Cronin AA, Sebayang SK, Nandy R. Determinants of stunting in Indonesian children: evidence from a cross-sectional survey indicate a prominent role for the water, sanitation and hygiene sector in stunting reduction. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1–11.

Katona P, Katona-Apte J. The interaction between nutrition and infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(10):1582–8.

Shrestha A, Six J, Dahal D, Marks S, Meierhofer R. Association of nutrition, water, sanitation and hygiene practices with children’s nutritional status, intestinal parasitic infections and diarrhoea in rural Nepal: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–21.

Hossain MM, Abdulla F, Rahman A. Prevalence and risk factors of underweight among under-5 children in Bangladesh: evidence from a countrywide cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(4): e0284797.

Shahid M, Ahmed F, Ameer W, Guo J, Raza S, Fatima S, Qureshi MG. Prevalence of child malnutrition and household socioeconomic deprivation: a case study of marginalized district in Punjab, Pakistan. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(3): e0263470.

Sharaf MF, Mansour EI, Rashad AS. Child nutritional status in Egypt: a comprehensive analysis of socioeconomic determinants using a quantile regression approach. J Biosoc Sci. 2019;51(1):1–17.

Al Banna MH, Hamiduzzaman M, Kundu S, Ara T, Abid MT, Brazendale K, Seidu A-A, Disu TR, Mozumder NR, Frimpong JB. The association between bangladeshi adults’ demographics, personal beliefs, and nutrition literacy: evidence from a cross-sectional survey. Front Nutr. 2022; 9.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Australian National University for University Research Scholarship with HDR Fee Merit Scholarship and Measure DHS for getting access to the BDHS-2018 dataset. Kinley Wangdi is funded by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grants (2008697).

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SM performed the whole analysis and drafting of the manuscript, HS developed the main conceptual ideas and reviewed critically the drafted manuscript, KW contributed to extracting the data and verifying the analytical methods, MK and DJG revised it critically for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

We used secondary data for this study which is de-identified and freely accessible for research purposes from the Demographic and Health Survey website. The DHS surveys maintain all the protocols strictly to uphold the ethical standards at every stage of the survey where informed consent was given by each participants to be eligible for the interview. Since the data used for this study is secondary and was made public upon registration, ethics approval is not necessary.

consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

No conflict of interest exists for the authors in this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mondal, S., Wangdi, K., Gray, D.J. et al. Associations between childhood malnutrition, socioeconomic inequalities and sanitation in the coastal regions of Bangladesh. Discov Public Health 21, 6 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-024-00126-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-024-00126-9