Abstract

Background

Proper utilization of maternal healthcare services plays a major role on pregnancy and birth outcomes. In sub-Saharan Africa, maternal and child mortality remains a major public health concern, especially in least developed countries such as Togo. In this study, we aimed to analyze factors associated with use of maternal health services among Togolese women aged 15–49 years.

Methods

This study used data from third round of nationally representative Demographic and Health Survey conducted in Togo in 2013. Analysis included 4,631 women aged 15–49 years. Outcome variables were timely first antenatal care (ANC) visits, adequate ANC4 + visits, and health facility delivery. Data were analyzed using Stata version 16.

Results

Overall, proportion of maternal healthcare utilization was 27.53% for timely first ANC visits, 59.99% for adequate ANC visits, and 75.66% for health facility delivery. Our multivariable analysis showed significant differences among women in highest wealth quintile, especially in rural areas with increasing odds of timely first ANC visits (Odds ratio (OR) = 3.46, 95% CI = 2.32,5.16), attending adequate ANC visits (OR = 2.19, 95% CI = 1.48,3.24), and delivering in health facilities (OR = 8.53, 95% CI = 4.06, 17.92) compared to those in the poorest quintile. Also, women with higher education had increased odds of timely first ANC visits (OR = 1.37, 95% CI = 1.11,1.69), and attending adequate ANC visits (OR = 1.73, 95% CI = 1.42,2.12) compared to those with no formal education. However, having higher parity and indigenous beliefs especially in rural areas decreased odds of using healthcare services.

Conclusions

Findings from this study showed that socio-economic inequality and socio-cultural barriers influenced the use of maternal healthcare services in Togo. There is therefore a need to improve accessibility and the utilization of maternal healthcare services through women’s economic empowerment and education to reduce the barriers.

Plain language summary

Utilization of healthcare services by women of childbearing age has been shown to reduce maternal and child mortality. However, in sub-Saharan Africa, maternal and child mortality remains a major public health issue. This is especially the case in Togo, one of the smallest countries in West Africa. The objective of this study was to assess the factors associated with utilization of maternal healthcare services among Togolese women aged 15–49 years. This was a cross-sectional study that used data from the Togo 2013 Demographic and Health Survey, a nationally representative household survey of women of childbearing age in Togo. Findings from the current study showed that the overall proportion of maternal healthcare utilization was 27.53% for timely first antenatal care visits, 59.99% for adequate antenatal care visits, and 75.66% for health facility delivery. Also, this study found that socio-economic inequality and socio-cultural barriers influenced the use of maternal healthcare services in Togo. For instance, women in the highest wealth quintile, those with higher education, and those who were covered by health insurance had higher odds of utilizing maternal healthcare service. Whereas, women who had indigenous beliefs, those from other ethnicities, who lived in the Savanes and Plateaux regions, as well as those with higher parity had lower odds of using maternal healthcare services. The results indicate that there is an urgent need to promote women’s economic empowerment and education to improve accessibility and the utilization of maternal healthcare services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In 2017, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) report, more than 295 000 women died worldwide from preventable causes due to pregnancy or childbirth, which represented approximately an average of 810 maternal deaths per day [1, 2]. Most of these maternal deaths (94%) occurred in low- or middle-income countries (LMICs), especially in sub-Saharan Africa where two-thirds (66%) of global maternal deaths are reported [2, 3]. Despite more than a 38% decline in maternal deaths globally, from 342 to 211 deaths per 100,000 livebirths, between 2000 and 2017, the maternal deaths ratio is still unacceptably high [2, 4]. Also, still between 2000 and 2017, the sub-Saharan African maternal mortality ratio stood at 542 maternal deaths per 100,000 livebirths higher than the global ratio of 216 deaths per 100,000 livebirths [3, 5].

To prevent and reduce these maternal deaths, numerous interventions have been developed. One of such interventions is the UN’s adoption of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—the target of one of the SDG-3 is reducing the global maternal deaths to less than 70 deaths per 100,000 livebirths by 2030 [6, 7]. Also, in 2021, five new targets were established to help countries get back on track in decreasing maternal deaths and tracking progress against the SDGs. Of these, the first three targets requires that 90% of pregnant women must attend ANC4 + visits, 90% of births are attended by skilled health personnel and 80% of women who gave birth must have accessed prenatal care (PNC) [7]. Despite these, the world is not on pace to meet the SDG-3 target of reducing maternal deaths [7] and low maternal health care service utilization remains a public health concern for LMICs, due to inequalities in access to quality health services, limited skilled health personnel and the wide gap between the rich and the poor which has increased the healthcare systems challenges [2, 8].

In sub-Saharan Africa for example, only 43% of pregnant women received ANC4 + visits compared to the global average of 55%, and 49% of deliveries are attended by skilled health personnel compared to the global average of 70% [9]. In Togo, physical access to care is rated very low for nearly all regions of the country, except for Lomé where the performance of the health system is acceptable. The lack of health infrastructure and limited physical access to health facilities is a major barrier to the use of maternal health services in this country [10, 11]. A third (33%) of people live outside a radius of 5 km from a health facility and there is a lack of ambulances (0.22 ambulances per health facility) with a weak referral systems [12]. In addition to the weak infrastructure (lack of electricity, water, drugs, and equipment), the skills of some health professionals are weak due to the low quality of training, poor working conditions, and unequal distribution of personnel over the national territory [12].

A number of studies have documented that socio-economic inequalities are implicated in the underutilization of maternal healthcare services [13, 14]. For instance, evidence indicates that socio-economic barriers are closely linked to the basic health coverage of the population which remains very low in Africa [15, 16]—only 48% of the continent’s population have access to the healthcare services they need [17, 18]. In Togo, only 7.6% of the population was covered by a health system of financial risk protection in 2016 compared to an average of 17% in sub-Saharan Africa, and 51% of health spending was supported by households through direct payments [19]. Direct payments for health remains very significant and are often a source of impoverishment of the population [12, 19].

Finally, apart from socio-economic inequalities and physical barriers, sociocultural factors may also limit access to maternal health care services. This includes ethnicity, religion, household decision-making, gender and autonomy, information, and education. These sociocultural factors pose significant barriers in Africa [20, 21]. In fact, they vary considerably not only between individual countries but also between different communities. For instance, in Burkina Faso, key predictors of home births are distance from the household to the health center, prenatal visits, prior experience of giving birth at home, fear of caesarean delivery, and lack of transport to go to health center [22]. This shows that there are many factors that determine access to maternal services. Some are common to many of the countries, but specificities exist. A specific study adapted to the context of each country on the determinants of the use of maternal health services is essential to identify them, consider corrective policy actions and suggest the appropriate strategies. This study was therefore undertaken to analyze the determinants affecting the use of maternal health services among Togolese women aged 15 to 49 years.

Methods

Study setting

Togo is one of the smallest countries in West Africa, with a land surface area of 56,785 km2 and an estimated population of 8,848,699 of which majority are females [23].

According to the World Bank (2022), less than half of the population live in urban areas, over 50% of the population are Christians and about 33% have indigenous beliefs [23]. Over half of the population live on less than $1.90 a day despite the country’s economic growth of 4.4% and global efforts made by the government to attract investment and encourage development [24].

Data source and sampling technique

In this study, we used secondary data from the most recent 3rd Togo Demographic and Health Survey (TDHS-3) which was conducted between November 2013 to April 2014. This cross-sectional survey was carried out by the National Institute of Statistics Economical Studies and Demographic (INSEED) in collaboration with the Ministry of Health (MoH) of Togo. The survey was financed by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and other international donors with the technical assistance of the International Coaching Federation (ICF) International, Inc.

The 2013 TDHS-3 employed a stratified two-stage cluster design to select the study participants. In the first stage, 330 primary survey units or clusters (128 in urban areas vs 202 in rural areas) were systematically selected with probability proportional to the unit size from the list of Enumeration Areas established during the General Census of Population and Housing conducted in 2010 by the INSEED. In the second stage, a sample of 30 households were selected systematically with equal probability from the list of households in each primary unit [25]. In this survey, 9697 eligible women aged 15–49 years were identified for an interview from 9549 households interviewed, of whom 9,480 women were successfully interviewed with a response rate of 98% (urban 97 vs. 99% rural). For this study, only participants who provided data on maternal healthcare utilization were selected for analysis. The unit of analysis for this study were individual women who were of childbearing age in Togo. Further details of the survey have been published elsewhere [25].

Variables

Outcome variables

The dependent variables in this study were timing of the first ANC visit, adequate number of ANC visits, and place of delivery.

Measurement of variables

Timing of the first ANC visit is defined as attending the first ANC visit within the first three months of pregnancy. This variable was coded as “1” (early initiation) if the participants reported attending the first ANC visit within the first trimester and “0” (late initiation) if after three months of conception [26, 27].

Adequate ANC visits are defined as receiving at least four ANC visits during the last pregnancy. Adequacy of ANC was coded as “1” (adequate) if participants had ANC4 + visits during their last pregnancy and “0” (inadequate) if less than four visits [28,29,30].

Place of delivery is categorized as health facility (public or private hospital, clinic, medico-social center, community health center) and “home” if the childbirth took place at respondent’s home [31, 32].

Explanatory variables

Our independent variables were the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants which included age (15–24, 25–34, and 35–49), education status (No education, primary, secondary/higher), religion (Christian, Muslim, indigenous believer), ethnicity (Adja-ewe/Mina, Kabye/Tem, Akposso/Akebou, Ana-ife, Para-gourma/Akan, Other and Non-Togolese), type of residence (urban or rural), region (Grande Agglomeration de Lomé, Maritime, Plateaux, Centrale, Kara and Savanes), health insurance (No and Yes), parity (None, 1–2, 3–4 and > 4), last child wanted (No and Yes), currently employed (No and Yes), and wealth index (poorest, poorer, middle, richer and richest).

Statistical analyses

Data analysis was performed using Stata version 16 statistical software. Because of the clustered nature of the data, we used complex sampling method, taking into consideration sampling strata, weight, and primary sampling units by using the svy (survey) command. In the first step, we used descriptive analysis to calculate the frequencies, percentages, and cumulative percentages for explanatory variables. In the second step, bivariate and multivariable analyses were conducted. The bivariate analysis comprised of sociodemographic characteristics as explanatory variables and use of maternal healthcare services as the outcome variables. Unadjusted odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals and p-values were calculated and all explanatory variables that were significant (with p-values < 0.05) were considered as having a potential association with the outcome variables and were selected and added to the multivariable logistic regression model.

The multivariable analyses were performed to calculate the odds of the association between the use of maternal healthcare services (outcome variables) and socio-demographic characteristics (explanatory variables) that were significant in the bivariate analysis. Adjusted odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals and p-values were also computed and all explanatory variables with a p-value < 0.05 in the multivariable analysis were considered as having a statistically significant association with use of maternal healthcare services (outcome variables). Three outcome variables were presented in tables, each divided into two subsamples: urban and rural. For all regression analyses, the odds ratios (OR) were presented along with their corresponding 95% Confidence Interval (CIs), and p-values. We also checked for multicollinearity using the VIF (Variance inflation factor) method, and the value was < 10 (Mean = 1.74, Minimum = 1.03, Maximum = 3.72) which indicated no multicollinearity among the variables. Associations with p-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

This study used secondary data which is available in the public domain (https://dhsprogram.com/data/dataset/Togo_Standard-DHS_2013.cfm?flag=0); no further ethical procedures were therefore required for this study.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the women who participated in the present study (n = 4631). Two thousand two hundred and twenty-two (47.98%) of the participants were in the age-group of 25–34 years, over two-fifth (41.48%) had no formal education, and about half (50.81%) were Christians. More than a quarter (29.02%) of the participants were from the Para-gourma/Akan ethnicity, most of them (68.34%) lived in rural areas and about one-fifth (22.95%) were from Savanes region. The majority of the women (96.07%) reported having no health insurance, more than two-fifth (40.36%) had a parity less than three and over than nine-tenths (93.44%) reported wanting their last child. More than four fifth (83.24%) had occupations and over a quarter (28.01%) were from household in the poorest wealth quintile.

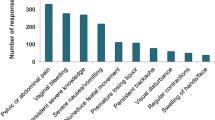

Figure 1 shows that nearly three quarters of the women (72.47%) attended their first ANC visit late, about three-fifth (59.99%) had made an adequate number (four or more) of ANC visits during their pregnancy, and about three quarters (75.66%) gave birth in a hospital.

Factors associated with timing of first ANC visits in Togo

Table 2 shows the factors associated with timing of first ANC visits. In the bivariate analysis, all variables that had p-values < 0.05 were selected and added to the multivariable logistic regression model. The findings showed that women with secondary and higher education had higher odds of timely first ANC visit (OR = 1.37, 95% CI = 1.11,1.69) compared to those with no formal education. Stratified by areas, this positive association was true for urban women only (OR = 1.67, 95% CI = 1.20,2.33). For place of residence, rural women had increased odds of timely first ANC visits (OR = 1.61, 95% CI = 1.16,2.22), compared to those living in urban areas (Table 2). Also, women who were covered by health insurance had increased odds of early first ANC visits (OR = 1.93, 95% CI = 1.39,2.67). Upon stratification by areas, this association was significant for both urban (OR = 2.07, 95% CI = 1.33,3.22) and rural (OR = 1.69, 95% CI = 1.02,2.79) areas. In addition, women who were from the rich and richest wealth quintile, especially in the rural areas had increased odds of timely initiation of ANC visits (OR = 1.90, 95% CI = 1.35,2.67) and (OR = 3.46, 95% CI = 2.32,5.16) compared to those from the poorest wealth quintile.

However, findings from this study also showed that women who had indigenous beliefs especially in the rural areas had lower odds of timing of first ANC visits (OR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.64, 0.95) compared to those who were Christians. Regarding ethnicity, the odds of early first ANC visits were significantly lower among women who were from other ethnicities, especially in the rural areas (OR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.27, 0.98) compared to those from Adja-ewe/Mina ethnicity. As for regional differences, in general, women who were from all the regions especially in the urban areas had lower odds of timely first ANC visits compared to those from Grande Agglomération de Lomé. Concerning the parity, we found that women with higher parity (> 4), especially in the urban areas had lower odds of timing of first ANC visit (OR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.44, 0.91) compared to those with lower (1–2) parity.

Factors associated with adequacy of ANC visits in Togo

Table 3 shows the factors associated with adequacy of ANC visits in Togo. In the bivariate analysis, all variables with p-values < 0.05 were selected and added to the multivariable logistic regression model. In this model, we found that women in the age-group 25–34 years and 35–49 years had increased odds of attending adequate number of ANC visits (OR = 1.53, 95% CI = 1.27,1.84) and (OR = 1.61, 95% CI = 1.27,2.05) respectively compared to those aged 15–24 years. Compared to women with no formal education, those who had primary and secondary/higher education especially in both urban and rural areas had increased odds of attending adequate ANC visits (OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.06,1.45), and (OR = 1.73, 95% CI = 1.41,2.12) respectively. Being covered by health insurance especially in the urban areas had increased odds of attending adequate number of ANC visits (OR = 1.52, 95% CI = 1.03,2.24) compared to those who were not covered with any health insurance. Similarly, being currently employed was positively associated with higher odds of receiving adequate ANC visits (OR = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.11,1.55) compared to those who were unemployed. Also, the odds of attending adequate ANC visits were significantly higher among women who were from the rich and richest wealth quintile (OR = 1.78, 95% CI = 1.29,2.45), and (OR = 2.19, 95% CI = 1.48,3.24) respectively compared to those from the poorest wealth quintile. Upon stratification by areas, this was true for rural women only.

However, our results also showed that the probability of attending adequate ANC visits were significantly lower among women who had indigenous beliefs especially in the rural areas (OR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.64,0.88) compared to those who were Christians. Also, women who were from Plateaux and Savanes regions had lower odds of attending adequate ANC visits (OR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.55,0.99), and (OR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.45,0.88) respectively compared to those from Grande Agglomération de Lomé. Lastly, having 3–4, and > 4) parity had lower odds of attending adequate ANC visits (OR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.65,0.94), and (OR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.61,0.94) respectively compared to those with lower parity.

Factors associated with health facility delivery in Togo

Table 4 shows the factors associated with health facility delivery in Togo. In this Table, results of a bivariate analysis are presented and all factors with p-values < 0.05 were selected and added to the multivariable logistic regression model. Women aged 25–34 years and 35–49 years especially in the rural areas had higher odds of delivering in a health facility (OR = 1.48, 95% CI = 1.15,1.91), and (OR = 1.59, 95% CI = 1.16,2.18) respectively compared to those aged 15–24 years. Also, women with primary and secondary / higher level of education in both urban and rural areas had higher odds of delivering in a health facility (OR = 1.62, 95% CI = 1.34,1.96), and (OR = 3.47, 95% CI = 2.55,4.73) respectively compared to those with no formal education. Concerning health insurance, we found that women who were covered by health insurance especially in the rural areas had 2.36 times higher odds of delivering in a health facility (OR = 2.36, 95% CI = 1.12,4.94) compared to those who were not covered by health insurance. For occupation status, we found that currently employed women in the urban areas only had higher odds of delivering in a health facility (OR = 2.18, 95% CI = 1.16,4.09) compared to those who were unemployed. We found also that belonging to the rich and richest wealth quintile was significantly associated with higher odds of delivering in a health facility (OR 6.75, 95% CI = 4.05,11.30), and (OR = 8.53, 95% CI = 4.06,17.92) respectively compared to those from the poorest wealth quintile.

However, findings from this study also showed that the odds of delivering at a health facility were significantly lower among women with indigenous beliefs (OR = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.49,071) and higher among those who were Muslin in their faith (OR = 1.36, 95% CI = 1.07,1.74) compared to those who were Christians. Stratified by areas, this association was significant in the rural areas only. Lower odds of delivering in a health facility were also found among women who were from Kabye/Tem (OR = 0.73, 95% CI = 0.55,0.97), Akposso/Akebou (OR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.38,0.90), Para-gourma/Akan (OR = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.43,0.82) and other (OR = 0.60, 95% CI = 0.37,0.98) ethnicities compared to those from Adja-ewe/Mina ethnicity. Compared to residents of Grande Agglomeration de Lomé, those in other regions (except for Maritime and Centrale region) had lower odds of delivering at a health facility. This regional difference was true only for rural residents, except for Maritime region. Also having higher parity (> 4) was significantly associated with lower odds of delivering in a health facility (OR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.47,0.83) compared to those of lower (1–2) parity. This association was similar for rural women only (OR = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.49,088).

Discussion

This cross-sectional study identified the proportion and factors associated with utilization of maternal healthcare services (timing of first ANC visits, adequate ANC visits, and healthcare facility delivery), using the 2013 TDHS-3 dataset.

The overall proportion of maternal healthcare utilization was 27.53% for timing of first ANC visits, 59.99% for adequate ANC visits, and 75.66% for delivery at a healthcare facility. These findings agrees with results of previous cross-sectional studies conducted in Ethiopia [33], and Cameroon [34] in which a higher proportion of timing of initiation of ANC visits was reported. Regarding adequate number of ANC visits, our finding is similar to findings of the systematic review conducted in Nepal [35] and dissimilar to a cross-sectional study done in Bangladesh [29]. In terms of health facility use, consistent findings are also reported from cross-sectional studies conducted in Ghana [36], and Senegal [37].These differences could be explained by socio-economic inequalities, socio-cultural barriers, limited and poorly equipped health facilities and poor quality of health services offered to women. There is a need to equip healthcare facilities, improve health service quality, educate women on the utilization of these facilities for delivery services and a need for women empowerment.

In our multivariable model, we found that age, education, religion, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, urban vs rural residence, region of residence, parity, and health insurance are variables that can help explain differential access to maternal healthcare services in Togo. For instance, women with higher age compared to those with lower age had higher odds of using the maternal healthcare services, except for timing of initiation of ANC visits. These findings are largely similar to those in other low and middle-income countries where advanced maternal age showed a positive association with the attendance of ANC4 + visits [38] and delivering in a health facility [39]. This is perhaps because, pregnant women with higher ages are at higher risk of experiencing complications during delivery, hence, they are more knowledgeable about the maternal healthcare services. In contrast, pregnant women with younger ages might be more immature and might have limited information about pregnancy and the utilization of prenatal and postnatal care services.

Also, this study’s findings adds to those of previous studies showing that with increase education there is a greater likelihood of a timely first ANC visit [33, 40], having adequate ANC visits [41, 42], and delivering at a health facility [43, 44], compared to those with no formal education. The possible reason for this could be that educated women are more informed and can make better decisions in favor of attending ANC visits and using health facility delivery services. Evidence further shows that one year of schooling for a mother reduces the risk of death in children under 5 by 3% [45]. As such, women education needs to be promoted in order to achieve sustainable maternal health.

In the current study, significantly lower odds of early first ANC visits was found among women from other ethnicities compared to those from Adja-ewe/Mina ethnicity. Beside this, we also found lower odds of delivering in a health facility among women from Kabye/Tem, Akposso/Akebou, Para-gourma and other ethnicities compared to those from Adja-ewe and Mina ethnicity. This finding was supported by other previous studies in which maternal ethnicity was found to be a predictive factor of underuse of maternal healthcare services [46, 47]. These ethnic differences could be due to women’s lack of confidence and understanding of the maternal healthcare services, and other cultural factors that can impact women’s healthcare seeking behavior.

Our study also found that women who were covered by health insurance especially in the rural areas had increased odds of attending the first ANC visits within the first trimester, receiving adequate ANC visits, and delivering at health facility compared to those who were not covered by health insurance. These findings agree with the findings of a study conducted in Jordan in which health insurance coverage was significantly associated with higher odds of utilizing maternal healthcare services [48]. This could be because women without health insurance face financial barriers to accessing healthcare.

Furthermore, socioeconomic factors were also found to be significantly associated with the odds of using maternal healthcare services. For instance, women in the rich and richest wealth quintile, especially in the rural areas had higher odds of timely first ANC visits, attending adequate ANC visits and delivering at health facility compared to those from the poorest wealth quintile. This aligns with previous studies done in Ethiopia [49], Gabon [9], and Ghana [50]. One explanation of this could be that women of higher socioeconomic status have the financial resources to seek health compared to those of lower-income families [51]. We perceive that there is a need to promote women’s economic empowerment to improve utilization of maternal healthcare services.

For occupational status, women who were currently employed compared to those who were unemployed showed a positive effect on having adequate ANC visits, and health facility delivery. These were supported by findings from previous studies that reported that employed women were more likely than unemployed women to attend ANC4 + visits [52], and deliver at health facility [53]. This could be because currently employed women have the financial means to afford health care services for their well-being and that of their future babies.

In this study, area of residence and regional differences played an important role in the odds of utilizing maternal healthcare services. As such, women in the rural areas had higher odds of timely first ANC visits compared to those in the urban areas. For adequate ANC visits and health facility, area of residence did not show any significant results. These findings are well in line with the literature indicating that women especially those in the rural areas were less likely to have ANC4 + visits [54,55,56], and deliver at a health facility [57, 58]. We perceive that this could be attributed to socio-economic disparities and socio-cultural factors—rural woman are financially dependent on their husband / partner and have lower income, they are less educated and are less informed on the importance of accessing maternal healthcare services than those from urban areas.

Similarly, we also observed the lowest odds of using maternal healthcare services among women from all other regions compared to those from Grande agglomeration de Lomé region. Stratified by areas, this association is similar in the urban areas and dissimilar in the rural areas. This might be due to the regional disparities in access to utilization of healthcare services.

Interestingly, our model also showed that women with indigenous beliefs especially in rural areas had lower odds of timing of first ANC visits, having adequate ANC visit and delivering in a health facility compared to those who were Christians. In contrast, women who were Muslim had higher odds of delivering at a health facility compared to those who were Christians. Although there is no clear explanation for this, a study has suggested that a number of Muslim women are betrothed to influential Muslim men which compels and facilitates the women to seek and access ANC services [57].

In addition to this, our study also showed a negative association between higher parity and all outcome variables. Evidence from previous studies showed that higher parity was significantly associated with lower odds of early booking of ANC visits [59], attending adequate ANC visits [60, 61], and delivering at a health facility [62]. Also, studies by Mugambe et al. and Gitonga and Muiruri done in Uganda and Kenya respectively identified having higher parity as a predictive factor of women’s under-use of health facility delivery [63, 64]. The possible justification may be that woman with prior experience with delivery were less motivated to use ANC visits or deliver at health facility which have been reported previously in other studies [65, 66].

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study is the use of nationally representative datasets – DHS-3; therefore, the results can be generalized especially for women aged 15–49 years in the whole country, although the sample size may not be large enough for the analysis of some subcategories. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to analyze the social determinants affecting the use of maternal healthcare services in Togo using DHS-3 datasets. However, this study has a few limitations to report. Firstly, a cross-sectional design was used, and this makes it hard to establish causal relationships from the associations between explanatory and outcome variables. Secondly, this study used secondary data and all the information given by the respondents about the outcome variables (such as timing and number of ANC visits, and health facility) and explanatory variables (such as last child wanted) were based on self-reported information, hence the chances of recall and social desirability biases abound.

Conclusion

Overall, our findings indicate that advanced maternal age, maternal education, health insurance, having an occupation, and being part of the rich and richest wealth index are significantly associated with increased odds of using maternal healthcare services. Apart from women who lived in the rural areas, region of residence, ethnicity, having indigenous beliefs, as well as having higher parity was negatively associated with the likelihood of utilizing all the maternal healthcare services. These findings warrant that future research should be done to establish the causality links between social determinants of health and utilization of maternal healthcare services. Our results suggest that there is a need to improve access to, and the utilization of maternal healthcare services in Togo by addressing socio-economic and socio-cultural barriers.

Data availability

The dataset is freely accessible for download from the Demographic and Health Surveys program (https://dhsprogram.com/data/dataset/Togo_Standard-DHS_2013.cfm?flag=0).

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ICF:

-

International Coaching Federation

- INSEED:

-

National Institute of Statistics Economical and Demographic

- LMICs:

-

Low- or middle-income countries

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SDGs:

-

Sustainable Development Goals

- TDHS:

-

Togo Demographic and Health Survey

- UN:

-

United Nations

- USAID:

-

United States Agency for International Development

- VIF:

-

Variance Inflation Factor

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Rahman MA, Rahman MA, Rawal LB, Paudel M, Howlader MH, Khan B, et al. Factors influencing place of delivery: evidence from three south-Asian countries. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0250012. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250012.

WHO. Maternal mortality [Internet]. 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality. Accessed 8 Aug 2022.

Musarandega R, Nyakura M, Machekano R, Pattinson R, Munjanja SP. Causes of maternal mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of studies published from 2015 to 2020. J Glob Health. 2021;11:04048.

Sitaula S, Basnet T, Agrawal A, Manandhar T, Das D, Shrestha P. Prevalence and risk factors for maternal mortality at a tertiary care centre in Eastern Nepal- retrospective cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:471. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03920-4.

Boldosser-Boesch A, Brun M, Carvajal L, Chou D, de Bernis L, Fogg K, et al. Setting maternal mortality targets for the SDGs. Lancet. 2017;389:696–7.

Armstrong-Mensah E, Dada D, Bowers A, Muhammad A, Nnoli C. Geographic, health care access, racial discrimination, and socioeconomic determinants of maternal mortality in Georgia, United States. Int J Matern Child Health AIDS. 2021;10:278–86.

WHO. New global targets to prevent maternal deaths [Internet]. https://www.who.int/news/item/05-10-2021-new-global-targets-to-prevent-maternal-deaths. Accessed 8 Aug 2021.

Yaya S, Uthman OA, Amouzou A, Ekholuenetale M, Bishwajit G. Inequalities in maternal health care utilization in Benin: a population based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:194. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1846-6.

Sanogo NA, Yaya S. Wealth status, health insurance, and maternal health care utilization in Africa: evidence from Gabon. BioMed Res Int. 2020;2020:4036830.

Arnold J, Samson M, Schechter J, Goodwin AS, Braganza S, Sesso GC, et al. Getting there: overcoming barriers to reproductive and maternal health services access in Northern Togo—a qualitative study. World Med Health Policy. 2016;8:223–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/wmh3.195.

Atake E. Socio-economic inequality in maternal health care utilization in Sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from Togo. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2021;36:288–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3083.

Ministry of Health of Togo. Plan National de développement sanitaire:2017–2022.

He Z, Zhang C, Wang S, Bishwajit G, Yang X. Socioeconomic determinants of maternal healthcare utilisation in Zambia: 1997–2014. Inq J Med Care Organ Provis Financ. 2021;58:00469580211067480.

Omer S, Zakar R, Zakar MZ, Fischer F. The influence of social and cultural practices on maternal mortality: a qualitative study from South Punjab. Pakistan Reprod Health. 2021;18:97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01151-6.

Alamneh TS, Teshale AB, Yeshaw Y, Alem AZ, Ayalew HG, Liyew AM, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in barriers for accessing health care among married reproductive aged women in sub-Saharan African countries: a decomposition analysis. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22:130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01716-y.

Gordon T, Booysen F, Mbonigaba J. Socio-economic inequalities in the multiple dimensions of access to healthcare: the case of South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:289. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8368-7.

Cullinan K. Universal Health Coverage: Only Half Of Africans Have Access To Health Care - Health Policy Watch [Internet]. 2021. https://healthpolicy-watch.news/only-half-of-africans-have-access-to-health-care/. Accessed 8 Aug 2022.

Muanya C. Only 48% of Africans receive health care they need, says UHC report [Internet]. Guard. Niger. News - Niger. World News. 2021. https://guardian.ng/features/only-48-of-africans-receive-health-care-they-need-says-uhc-report/. Accessed 8 Aug 2022.

WHO. WHO country cooperation strategy at a glance: Togo [Internet]. 2016. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-CCU-16.03-Togo. Accessed 8 Aug 2022.

Barbi L, Cham M, Ame-Bruce E, Lazzerini M. Socio-cultural factors influencing the decision of women to seek care during pregnancy and delivery: a qualitative study in South Tongu District. Ghana Glob Public Health. 2021;16:532–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1839926.

Yarney L. Does knowledge on socio-cultural factors associated with maternal mortality affect maternal health decisions? A cross-sectional study of the Greater Accra region of Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2197-7.

Kouanda S, Bado A, Meda IB, Yameogo GS, Coulibaly A, Haddad S. Home births in the context of free health care: The case of Kaya health district in Burkina Faso. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2016;135:S39-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.08.009.

World Bank. Togo Population 2022 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs) [Internet]. 2022 https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/togo-population. Accessed 4 Sep 2022.

Stebbins S. These are among the 25 poorest countries in the world [Internet]. USA TODAY. 2020. https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2019/07/07/afghanistan-madagascar-malawi-poorest-countries-in-the-world/39636131/. Accessed 4 Sep 2022.

DHS. Enquête Démographique et de santé du Togo. 2013.

World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

Tola W, Negash E, Sileshi T, Wakgari N. Late initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic of Ilu Ababor Zone, southwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16: e0246230.

Benova L, Tunçalp Ö, Moran AC, Campbell OMR. Not just a number: examining coverage and content of antenatal care in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3: e000779.

Sarker BK, Rahman M, Rahman T, Rahman T, Khalil JJ, Hasan M, et al. Status of the WHO recommended timing and frequency of antenatal care visits in Northern Bangladesh. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0241185. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241185.

Kpordoxah MR, Issah A-N, Yeboah D, Mruts KB, Boah M. Assessing the association between an early and recommended number of focused antenatal care visits and the number of prenatal care content received before delivery in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2023;18: e0282694.

Bolarinwa OA, Fortune E, Aboagye RG, Seidu A-A, Olagunju OS, Nwagbara UI, et al. Health facility delivery among women of reproductive age in Nigeria: does age at first birth matter? PLoS ONE. 2021;16: e0259250.

Dessie AM, Anley DT, Zemene MA, Aychew EW, Debebe HG, Misganaw NM, et al. Health facility delivery service utilization and its associated factors among women in the pastoralist regions of Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6: e1183.

Seid A, Ahmed M. Survival time to first antenatal care visit and its predictors among women in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0251322. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251322.

Appiah F. Individual and community-level factors associated with early initiation of antenatal care: Multilevel modelling of 2018 Cameroon Demographic and Health Survey. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0266594. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0266594.

Toolan M, Barnard K, Lynch M, Maharjan N, Thapa M, Rai N, et al. A systematic review and narrative synthesis of antenatal interventions to improve maternal and neonatal health in Nepal. AJOG Glob Rep. 2022;2:100019.

Kumbeni MT, Apanga PA. Institutional delivery and associated factors among women in Ghana: findings from a 2017–2018 multiple indicator cluster survey. Int Health. 2021;13:520–6.

Zegeye B, Ahinkorah BO, Idriss-Wheelr D, Oladimeji O, Olorunsaiye CZ, Yaya S. Predictors of institutional delivery service utilization among women of reproductive age in Senegal: a population-based study. Arch Public Health. 2021;79:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-020-00520-0.

Adedokun ST, Yaya S. Correlates of antenatal care utilization among women of reproductive age in sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from multinomial analysis of demographic and health surveys (2010–2018) from 31 countries. Arch Public Health. 2020;78:134. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-020-00516-w.

Mehari M, Maeruf H, Robles CC, Woldemariam S, Adhena T, Mulugeta M, et al. Advanced maternal age pregnancy and its adverse obstetrical and perinatal outcomes in Ayder comprehensive specialized hospital, Northern Ethiopia, 2017: a comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-2740-6.

Manyeh AK, Amu A, Williams J, Gyapong M. Factors associated with the timing of antenatal clinic attendance among first-time mothers in rural southern Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-2738-0.

Ahinkorah BO, Seidu A-A, Budu E, Mohammed A, Adu C, Agbaglo E, et al. Factors associated with the number and timing of antenatal care visits among married women in Cameroon: evidence from the 2018 Cameroon Demographic and Health Survey. J Biosoc Sci. 2022;54:322–32.

Duodu PA, Bayuo J, Mensah JA, Aduse-Poku L, Arthur-Holmes F, Dzomeku VM, et al. Trends in antenatal care visits and associated factors in Ghana from 2006 to 2018. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04404-9.

Tesema GA, Tessema ZT. Pooled prevalence and associated factors of health facility delivery in East Africa: Mixed-effect logistic regression analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0250447. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250447.

Zhao J, Zhao Y, Du M, Binns CW, Lee AH. Maternal education and breastfeeding practices in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Midwifery. 2017;50:62–71.

Vart P. Understanding the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2022;399:1467.

Puthussery S, Tseng P-C, Sharma E, Harden A, Griffiths M, Bamfo J, et al. Disparities in the timing of antenatal care initiation and associated factors in an ethnically dense maternal cohort with high levels of area deprivation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22:713.

Huang Y, Shallcross D, Pi L, Tian F, Pan J, Ronsmans C. Ethnicity and maternal and child health outcomes and service coverage in western China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e39-56.

Fernandes P, Odusina EK, Ahinkorah BO, Kota K, Yaya S. Health insurance coverage and maternal healthcare services utilization in Jordan: evidence from the 2017–18 Jordan demographic and health survey. Arch Public Health. 2021;79:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-021-00605-4.

Shibre G, Mekonnen W. Socio-economic inequalities in ANC attendance among mothers who gave birth in the past 12 months in Debre Brehan town and surrounding rural areas, North East Ethiopia: a community-based survey. Reprod Health. 2019;16:99. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0768-88.

Yaya S, Da F, Wang R, Tang S, Ghose B. Maternal healthcare insurance ownership and service utilisation in Ghana: Analysis of Ghana Demographic and Health Survey. PLoS ONE. 2019;14: e0214841.

Fagbamigbe AF, Idemudia ES. Wealth and antenatal care utilization in Nigeria: Policy implications. Health Care Women Int. 2017;38:17–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2016.1225743.

Badolo H, Bado AR, Hien H, Allegri MD, Susuman AS. Determinants of antenatal care utilization among childbearing women in Burkina Faso. Front Glob Womens Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2022.848401.

Boah M, Mahama AB, Ayamga EA. They receive antenatal care in health facilities, yet do not deliver there: predictors of health facility delivery by women in rural Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1749-6.

Adewuyi EO, Auta A, Khanal V, Bamidele OD, Akuoko CP, Adefemi K, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with underutilization of antenatal care services in Nigeria: a comparative study of rural and urban residences based on the 2013 Nigeria demographic and health survey. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0197324. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197324.

Belay A, Astatkie T, Abebaw S, Gebreamanule B, Enbeyle W. Prevalence and factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care in rural areas of Southwestern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22:30.

Muchie KF. Quality of antenatal care services and completion of four or more antenatal care visits in Ethiopia: a finding based on a demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1488-0.

Ahinkorah BO, Seidu A-A, Budu E, Agbaglo E, Appiah F, Adu C, et al. What influences home delivery among women who live in urban areas? Analysis of 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey data. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0244811. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244811.

Kifle MM, Kesete HF, Gaim HT, Angosom GS, Araya MB. Health facility or home delivery? Factors influencing the choice of delivery place among mothers living in rural communities of Eritrea. J Health Popul Nutr. 2018;37:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-018-0153-1.

Woldeamanuel BT, Belachew TA. Timing of first antenatal care visits and number of items of antenatal care contents received and associated factors in Ethiopia: multilevel mixed effects analysis. Reprod Health. 2021;18:233.

Denny HM, Laksono AD, Matahari R, Kurniawan B. The determinants of four or more antenatal care visits among working women in Indonesia. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2022;34:51–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/10105395211051237.

Joshi C, Torvaldsen S, Hodgson R, Hayen A. Factors associated with the use and quality of antenatal care in Nepal: a population-based study using the demographic and health survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:94. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-94.

Moyer CA, Mustafa A. Drivers and deterrents of facility delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reprod Health. 2013;10:40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-10-40.

Gitonga E, Muiruri F. Determinants of health facility delivery among women in Tharaka Nithi county. Kenya Pan Afr Med J. 2016;25:9.

Mugambe RK, Yakubu H, Wafula ST, Ssekamatte T, Kasasa S, Isunju JB, et al. Factors associated with health facility deliveries among mothers living in hospital catchment areas in Rukungiri and Kanungu districts. Uganda BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:329.

Tekelab T, Chojenta C, Smith R, Loxton D. Factors affecting utilization of antenatal care in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0214848.

Abel Ntambue ML, Françoise Malonga K, Dramaix-Wilmet M, Donnen P. Determinants of maternal health services utilization in urban settings of the Democratic Republic of Congo–a case study of Lubumbashi City. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:66.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the DHS program for providing the survey data for free.

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KK and SY contributed to the conception and designed of the original study. SY and KK did the acquisition of data. KK, SY, MHC and RG conducted and performed the statistical analysis and interpreted the results. SY had final responsibility to submit for publication. All authors critically reviewed, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study used secondary data which is available online on the public space (https://dhsprogram.com/data/dataset/Togo_Standard-DHS_2013.cfm?flag=0); no further ethical procedures were required for the study.

Competing interests

Sanni Yaya is an Editor-in-Chief of Reproductive Health and was not involved in the peer-review or handling of the manuscript. The authors have no other competing interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kota, K., Chomienne, MH., Geneau, R. et al. Socio-economic and cultural factors associated with the utilization of maternal healthcare services in Togo: a cross-sectional study. Reprod Health 20, 109 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-023-01644-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-023-01644-6