Abstract

While the most important factors associated with facility-based delivery (FBD) have been explored within individual countries in Africa, no systematic review has explored the factors associated with FBD across sub-Saharan Africa. A systematic search of the peer-reviewed literature was conducted to identify articles published in English from 1/1995-12/2011 that reported on original research conducted entirely or in part in sub-Saharan Africa and included a primary outcome variable of FBD, delivery location, or skilled birth attendance (SBA). Out of 1,168 citations identified, 65 met inclusion criteria. 62 of 65 were cross-sectional, and 58 of 65 relied upon household survey data. Fewer than two-thirds (43) included multivariate analyses. The factors associated with facility delivery were categorized as maternal, social, antenatal-related, facility-related, and macro-level factors. Maternal factors were the most commonly studied. This may be a result of the overwhelming reliance on household survey data – where maternal sociodemographic factors are likely to be well-represented and non-maternal factors may be less consistently and accurately represented. Multivariate analysis suggests that maternal education, parity / birth order, rural / urban residence, household wealth / socioeconomic status, distance to the nearest facility, and number of antenatal care visits were the factors most consistently associated with FBD. In conclusion, FBD is a complex issue that is influenced by characteristics of the pregnant woman herself, her immediate social circle, the community in which she lives, the facility that is closest to her, and context of the country in which she lives. Research to date has been dominated by analysis of cross-sectional household survey data. More research is needed that explores regional variability, examines longitudinal trends, and studies the impact of interventions to boost rates of facility delivery in sub-Saharan Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2011, nearly half of all the women who died due to pregnancy-related causes were from sub-Saharan Africa [1]. Skilled birth attendance (SBA) is one of the main interventions to combat such deaths, prompting the World Health Organization to advocate for universal SBA [2]. In many countries, encouraging women to deliver in facilities is the most practical way to boost rates of SBA.

In much of sub-Saharan Africa, fewer than half of women deliver their infants in health facilities [3]. The reasons are myriad, and understanding these factors is critical to identifying gaps in the existing research, planning interventions, and developing effective policies for addressing low facility-based delivery rates.

Three previous reviews of the literature have addressed facility-based delivery (FBD) [4–6], yet none were systematic, comprehensive, and focused on sub-Saharan Africa. The first review was not systematic, was conducted nearly 20 years ago, and the bulk of its references come from the mid-1980s [4]. This review addressed the factors that influenced the delay in deciding to seek care, the delay in getting to a health facility, and the delay in obtaining adequate care. The authors suggest that distance, cost, and quality of care are not sufficient to predict service utilization – other factors such as illness severity and socioeconomic status influence service use. This review resulted in what has come to be known as the Three Delays Model, perhaps one of the most commonly utilized conceptual frameworks in the maternal mortality literature. The second review focused on quantitative assessments of the impact of maternal health interventions on utilization [5]. Included in the review were a total of 30 quantitative studies from around the world, only 8 of which included data from sub-Saharan Africa. Say and Raine concluded that there is enormous variability in maternal health service utilization, and that utilization appears to be extremely dependent upon contextual factors [5]. The third review centered its assessment on references identified in the previous two reviews [6]. The authors used the literature to categorize determinants of facility-based delivery into four main themes: sociocultural factors, perceived benefit or need of skilled attendance, economic accessibility, and physical accessibility [6]. The authors conclude from their review that most research downplays perceived need and physical accessibility as significant barriers. Note that this review was not limited to any geographic region or any specific year range.

Given inherent differences between sub-Saharan Africa and much of the rest of the developing world, a review that explicitly focuses on sub-Saharan Africa is critical. In addition, a reconsideration of the domains of influence is also overdue. Thaddeus and Maine [4] see delays in care seeking as the crux of the issue around facility delivery. Say and Raine [5] do not posit a framework for understanding delivery location. Gabrysch and Campbell [6] see accessibility factors (including perceived need) and sociocultural factors as the most important drivers of decision making. This review attempted to explore the research literature in Africa to revisit the potential domains of influence over delivery location in sub-Saharan Africa.

We conducted a systematic review of the research literature of empirical studies addressing factors associated with FBD to: 1) document the research designs and data collection methodology used to explore factors associated with facility-based delivery in the published literature; and 2) identify the factors that are most commonly associated with FBD or SBA in sub-Saharan Africa.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

A systematic search of the peer-reviewed, published literature from 1995 – 2011 was conducted to identify the factors associated with delivery care in sub-Saharan Africa. Searches used: Ovid MEDLINE, EBM Reviews, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, Journals@Ovid Full Text, CINAHL Plus with Full Text (EBSCO), PubMed, Africa-Wide Info, Psych Info, Global Health, Social Science Full Text, Google Scholar, BioMed Central, and African Journals Online. Initial searches were conducted on August 14 and September 5, 2011, and repeated on January 5, 2012.

The following key search terms were used in various combinations: maternal health services / utilization, developing country/ies, Africa, determinants or predictors, delivery services, facility-based delivery, facility delivery, institutional delivery, skilled birth attendance, skilled attendance, pregnancy. (Search strategy available upon request). Additional hand searching was conducted by reviewing the references of all retrieved studies.

Study selection and data extraction

Studies were included in the review if they were published in a peer reviewed journal in English between January 1995 and December 2011, were conducted entirely or in part in sub-Saharan Africa, reported on the results of original research, and included a primary outcome variable of FBD, delivery location, or SBA. Articles needed to address determinants, predictors, or factors associated with delivery location. Review articles were not included. Due to an explicit emphasis on identifying empirically-tested associations, qualitative studies were excluded.

Study inclusion was determined in a multi-step procedure. First, bibliographic data and abstracts were evaluated for concordance with formal inclusion rules. Note that this first stage included the search term “developing country” or “developing countries”, but did not explicitly focus on African nations. At this first, most conservative decision point, studies were removed from further review if they were conducted in a western setting, but those conducted in developing countries were retained for closer inspection. Studies that clearly did not meet the remaining inclusion criteria were discarded.

The remaining studies were selected for full-text retrieval. Publications that did not present empirical data or otherwise did not meet inclusion criteria were discarded, but not before hand-searching the references. Full-text of studies identified from the references were retrieved as well. In a final step, the remaining studies were examined in detail to identify the final sample of studies meeting all inclusion criteria.

Analysis and synthesis strategy

Given the variety of types of studies included in this systematic review – including descriptive and evaluative studies that ranged from simple bivariate analyses to complex multivariate modeling – a meta-analysis was neither possible nor appropriate. A table was created that listed all identified correlates of FBD. These correlates were grouped into categories: maternal factors, social factors, antenatal care-related factors, facility-related factors, and macro-level factors. The table also included a synthesis of findings indicating the direction of the relationship, the countries in which the research was conducted, and the citations associated with the research.

Each research study was coded independently by each author based a modified version of the STROBE statement [7]. The STROBE statement was used to develop a scale ranging from 0–34 points that covered such areas as study background, objectives, design, setting, participants, data collection methods, variables assessed, analysis methods, reporting of results, discussion of relevance to other literature, discussion of limitations, and inclusion of implications. Each item was scored on a 0–2 scale (0 = not included/addressed, 1 = somewhat included/addressed, 2 = clearly included/addressed). Total scores for each paper were compared across authors and averaged. Discrepancies of more than 4 points were discussed and consensus reached. Final averaged scores were divided into tertiles to determine the strength of the evidence, with those scoring in the lowest tertile providing ‘weak’ evidence, those scoring in the middle tertile providing ‘moderate’ evidence, and those in the top tertile providing ‘strong’ evidence.

Results

1,168 citations were identified, of which 123 were retrieved for full-text review. Most of the 1,045 eliminated were excluded due to western setting, lack of original data, or a primary outcome measure other than place of delivery. Of the 123 articles retrieved for full-text review, an additional 43 studies were identified by searching the references, most of which were published in non-indexed, regional journals. Thus a total of 166 articles were identified for full text review. Upon reviewing the full text, another 93 were removed for such reasons as being conducted outside sub-Saharan Africa, place of delivery not being the primary outcome, not including original data, using primarily qualitative methods, not being peer-reviewed, or full text not being available. This left 65 published studies that met all inclusion criteria and for which data were extracted. (See Figure 1; Additional file 1).

Of the 65 articles, the mean STROBE score was 25.7 out of a potential 34 (range 14.5 – 32.0). The distribution was skewed toward higher scores, with 50% of all articles rating higher than 26 out of 34. In 57 out of 65 articles (87.6%), the coders agreed within 2 points on the article’s quality score. Only 4 articles showed discrepancy of 4 points (the maximum discrepancy found), and none of the discrepancies transcended the tertile cut points. In other words, scores between reviewers may have been 4 points apart, but either reviewer’s score would have put it in the same quality tertile. Three of the four articles in question were in the middle tertile, and one was at the highest tertile. (Additional file 1 illustrates the summary of all articles reviewed, including their quality ratings in tertiles).

Pursuant to Aim 1 (document the research designs and data collection methodology used to explore factors associated with FBD in the published literature), all but 3 of the 65 published manuscripts included in this review were cross-sectional in nature. Ekirapa-Kiracho et al., 2011 [8], Penfold et al., 2007 [9], and Stanton et al., 2007 [10] were the only studies to include a longitudinal component, although none followed the same women over time. 58 out of the 65 studies (89.2%) reviewed relied upon population-based household surveys, including 20 that used national Demographic Health Survey data collected once every five years, and 6 that relied upon regional Health and Demographic Surveillance Site data, which are collected at least twice per year from small research outposts responsible for tracking the health and demographics of a surrounding population catchment area [11, 12]. Nine out of 65 studies (13.8%) used medical records or facility assessment data, 4 used facility-based surveys of women, and 2 used Geographic Information System data (See Table 1).

The sophistication of the data analysis varied widely. While 43 of the 65 studies (66%) included multivariate analysis, 20 (30.7%) included only descriptive statistics or a combination of descriptive statistics with bivariate associates explored. The remaining 2 studies utilized data compilation techniques to calculate rate ratios, odds ratios, or examine trends based on existing datasets [5, 10, 13].

Pursuant to Aim 2 (identify the factors that are most commonly associated with FBD or SBA in sub-Saharan Africa), Tables 2, 3, 4 illustrate the factors identified in the literature as being associated with delivery location. These factors were divided into the following categories: maternal factors, social factors, antenatal care-related factors, facility-related factors, and macro-level factors.

Table 2 addresses more than 30 different maternal factors that have been explored in sub-Saharan Africa pursuant to FBD, the most common being maternal education, urban/rural status, and socioeconomic status. A host of additional maternal factors were found to be associated with FBD, including parity, perceived need for FBD, having means of transport to a facility, previous delivery location, and perceived complications. Many of these variables have a consistent and predictable relationship with facility-based delivery – such as greater education and higher socioeconomic status generally predicting greater utilization of FBD services. Others appear to have differential effects, based upon the study locale, design, or population. For example, marital status appears to be linked to facility delivery in some studies, yet not in others. Female autonomy appears to be associated with greater facility delivery rates in some studies, yet other studies indicate a strong interaction effect with wealth, suggesting that women’s autonomy in the absence of material resources is insufficient to boost facility utilization.

Table 3 illustrates 15 different social factors found to be associated with FBD. Social factors include such things as non-male household head, husband’s occupation, husband’s education, small family norm, living in a socially disadvantaged neighborhood, or needing permission to go to a facility. Relative to the maternal factors described in Table 2, social factors appear to be much less studied, with 12 unique studies accounting for data pursuant to 15 identified social factors. The social factors most commonly cited as related to FBD include husband’s education and occupation, as well as a village-level variable regarding the percent of the community rating the local facility as excellent. In terms of direction of influence, women with more educated husbands or husbands in non-agricultural occupations are more likely to deliver in a facility. In addition, women in communities that rank their local facility as ‘excellent’ are more likely to deliver in a facility.

Table 4 illustrates the role antenatal care (ANC) may play in influencing facility based delivery. With one exception, the results suggest that all elements of ANC are linked to greater utilization of FBD services. Akazili et al. [49] found that in northern Ghana, women who presented for ANC during the third trimester were more likely to deliver in a facility than women presenting earlier. The authors speculate that may be a result of women with complications presenting late for ANC and being strongly encouraged to deliver at a facility.

Table 4 also illustrates the numerous facility-related factors that may influence whether women choose to deliver at home or in a facility. In this category, distance to facility is the most common factor studied and cited as a deterrent to FBD. In looking at the number of studies citing each factor, cost, perceived quality of care, and staff attitudes and behavior are the next most common facility-related factors identified in the literature.

Finally, Table 4 illustrates some of the macro-level factors that appear to be associated with FBD and SBA rates. SBA appears to be higher in countries in which the government spends a larger percentage of its spending on health and in which there is higher total health expenditure per capita. In addition, countries with higher rates of female literacy are likely to have higher rates of SBA than countries with lower female literacy rates.

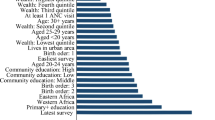

Out of the 43 manuscripts reviewed that used multivariate modeling, 37 reported one or more models in their results in sufficient detail to allow for comparison across studies. “Full” models ranged from those that included only three variables (e.g. Kruk et al., 2007 [23]; Mulogo et al., 2006 [24]; Penfold et al., 2007 [9]) to those that included 15 or more variables (e.g. Gabrysch et al., 2011 [69]; Spangler and Bloom, 2010 [50]; Stephenson et al., 2006 [14]). Across the multivariate models and among those studies deemed to be of moderate or strong quality, the factors that showed the greatest consistency in their association with FBD were maternal education, parity, household wealth, urban residence, distance to the nearest facility, and number of ANC visits. Table 5 illustrates those studies in which multi-variate models explored some or all of those factors, indicating the consistency of the findings across studies and across models (See Table 5). Only one of the published studies in this review included a model with all of these variables, finding all to be statistically significant [25]. Beyond these key variables, the host of additional factors studied in multivariate analysis were not consistently found to be associated with FBD. These included age-related variables, ethnicity, religion, marital status, partner’s occupation, previous health-related factors, and women’s autonomy.

Discussion

In summary, the vast majority of the empirical research conducted on FBD in sub-Saharan Africa is cross-sectional in nature and relies upon data from household surveys. In addition, the literature to date is variable in its quality and analytical sophistication. Maternal factors – especially sociodemographic factors – appear to have been the most frequently studied and are among the factors most commonly linked to FBD rates. This may be a result of the overwhelming reliance on household survey data – where maternal sociodemographic factors are likely to be well-represented and non-maternal factors may be less consistently and accurately represented. Nonetheless, a host of non-maternal factors spanning social, ANC, facility-related, and macro-level factors emerge from this literature and appear to be associated with FBD rates in sub-Saharan Africa.

One critical gap identified in this review of the literature is studies with a longitudinal design. In many studies, data are collected from women well after delivery, and women are queried about their decision-making regarding delivery location. Such a design asks women to reflect back on the reasons that compelled them to stay home or deliver in a facility. While this may be the most practical and feasible way to gather such information, it may be subject to recall bias and is likely to be influenced by women’s experiences during delivery. In contrast, much could be learned if attitudinal and behavioral data were collected from women throughout their pregnancies, further examining those data in the context of their ultimate delivery location.

Few studies to date have explored regional variability in FBD in a meaningful way. While many studies report regional differences, none adequately explored the factors underlying those differences beyond attributing them to socioeconomic status, rural/urban differences, or ethnicity. What is it about ethnicity, for example, that predisposes some women to deliver at home versus delivering in a facility? Is ethnicity a proxy for education, or socioeconomics, or rural/urban status? And while socioeconomic status is seen as inextricably linked to FBD rates, why does socioeconomic status appear to be less important in countries with higher female literacy rates? [26].

Another gap in the FBD literature is the dearth of intervention studies. It is possible that there are simply not enough intervention studies underway or completed in the region to be able to generate peer-reviewed publications. It is also possible that the interventions underway focus on primary outcomes aside from FBD and thus were not picked up in this review. For example, Bellows et al. [73] conducted a systematic literature review regarding the use of vouchers to encourage reproductive health service use that was not discovered through this review. Yet that review included only three studies conducted in Africa, one on sexually transmitted infection care and maternity services in Uganda [74] and two on family planning in Kenya that included a maternity services component [74–76]. It is also possible that research capacity in many of the developing nations of sub-Saharan Africa is such that translating research results into submitted publications is hampered by limited human resources. Regardless, intervention studies are needed to determine how to successfully boost FBD rates in sub-Saharan Africa.

Research literature to date has relied heavily on household surveys, especially the Demographic Health Surveys conducted every five years in many developing countries. While such data are plentiful and readily available for analysis, it is important to recognize their limitations. First, household surveys are typically conducted through verbal interviews with women and/or heads of household, a format which can increase the risk of social desirability bias. Household surveys also limit the number and type of questions that can be asked, which may affect the ultimate conclusions drawn. For example, in this review 11 studies relying upon household data found that ANC use, frequency, and perceived quality are associated with a greater likelihood of FBD [14, 15, 25, 27–31, 50, 51, 54]. This finding contradicts some of the qualitative literature suggesting that women who are told they have “normal” pregnancies during antenatal care assume they will have “normal” deliveries and thus do not need to deliver in a facility [77, 78]. While these two seemingly discrepant findings may both be valid, note that the latter could not have been detected in a cross-sectional household survey.

In addition, household surveys are not ideal for measuring social norms, social networks, individual integration into social networks, availability of social support, community-level attitudes toward health behaviors, or decision-making patterns within extended families – all of which have the potential to vastly improve understanding of FBD in sub-Saharan Africa. Thus, another critical gap in the literature includes studies that move beyond household surveys to examine the social factors influencing delivery location.

Finally, this review illustrates the enormous variability with regard to the analysis of data associated with FBD. Nearly a third of the studies in this review were limited to descriptive and bivariate statistics. While such studies may provide insights into which variables require further research, multi-level and multi-variable modeling is important to advancing this literature. Nonetheless, caution is warranted: Results from sophisticated analytical procedures will only reflect the data being included in the models; and as described, key social and community-level components of the equation may be missing altogether.

This systematic review of the literature builds upon the previous reviews in several important ways. First, it focuses entirely on sub-Saharan Africa, explicitly including African journals. This is a departure from previous reviews. Thaddeus and Maine’s 1994 review, while generally focused on maternal mortality in Africa, included articles from Central and South America and across Asia and the Middle East [4]. Similarly Say and Rayne’s 2007 review [5] included only 8 articles from Africa, and Gabrysch and Campbell’s 2009 review [6] – which was based upon Thaddeus and Maine’s and Say and Rayne’s reviews – included studies across Latin America, Asia, and the Middle East. While such inclusivity might have been helpful at a time when there was comparatively little written about barriers to facility delivery, it is not nearly as useful today in planning interventions that speak to the local context. The review presented here focuses exclusively on the issues pursuant to the sub-Saharan African context, something that has been sorely missing in the published literature. In addition, this review sought to include original research from the African sub-continent that was not published in mainstream western literature. This has complicated the search strategy for this review, and admittedly, it has increased the variability of the quality of studies reviewed. However, many of the articles retrieved from the African journals included in this search have shed valuable light on the phenomenon of FBD that might have otherwise gone unnoticed.

This review challenges assumptions made in previous reviews about how to categorize the factors associated with FBD. This review proposes that the factors associated with facility delivery fall into five different categories: maternal, social, antenatal, facility-related, and macro-level factors. This categorization suggests a much broader lens than those posited previously. Maternal factors have always been a focal point of policy and programming, but social factors have received much less attention. Yet social factors such as community attitudes toward facility delivery are likely an important intervention point. This review also suggests that women’s experiences during ANC (and with the facility itself) may be extremely important in influencing future maternity service use. As such, the facility and those who staff it may be an important target of future interventions. In addition, researchers and policy makers must be mindful of the regional and national context. Low FBD rates may be a downstream effect of lack of national emphasis on education of girls, for example.

Despite its strengths, this review has several limitations worthy of note. First, the review was limited to articles published between 1995 and 2011. It is possible that having broadened the years of publication, the results may have been slightly different. Second, the review was limited to articles published in English and available via English-language search engines. This is an important limitation, given the number of Francophone countries in Africa and the likelihood that research coming from those countries may tell a very different story than those coming from English-speaking nations. By design, this review also focused upon quantitative studies that could provide statistical assessments of associations. The results may have been different – albeit perhaps more difficult to compare – if qualitative studies were also included in the assessment. This review was conducted by a small team of researchers, which may have affected the interpretation. The author was assisted in creating and implementing the search strategy by a master’s trained global health librarian, and the quality of the articles was judged by the author and a master’s level research associate. This small team was efficient, but it is possible that a larger team may have interpreted the literature slightly differently.

Conclusions

In conclusion, FBD is a complex issue that is influenced by a host of factors, including characteristics of the pregnant woman herself, her immediate social circle, the community in which she lives, the facility that is closest to her, and context of the country in which she lives. While multivariate analysis suggests that across sub-Saharan Africa, maternal education, parity, rural / urban residence, household wealth, distance to the nearest facility, and number of ANC visits are the factors most strongly and consistently associated with FBD, the literature suggests that dozens of additional factors appear to contribute to FBD rates in both bivariate and multivariate analyses. Further research is needed to determine the relative strength and the replicability of such findings, given the enormous variability seen within and across the nations of sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, longitudinal and intervention research are needed to advance understanding of how best to increase FBD in sub-Saharan Africa.

References

Lozano R, Wang H, Foreman KJ, Rajaratnam JK, Naghavi M, Marcus JR, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Lofgren KT, Phillips D, Atkinson C, Lopez AD, Murray CJ: Progress towards Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5 on maternal and child mortality: An updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011, 378 (9797): 1139-1165. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61337-8.

WHO: Making pregnancy safer: The importance of the skilled birth attendant; A joint statement by WHO, ACM, and FIGO. 2004, Geneva

Wang W, Alva S, Wang S, Fort A: Levels and trends in the use of maternal health services in developing countries. DHS Comparative Reports No. 26. 2011, ICF Macro: Calverton, Maryland

Thaddeus S, Maine D: Too far to walk: Maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med. 1994, 38 (8): 1091-1110. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7.

Say L, Raine R: A systematic review of inequalities in the use of maternal health care in developing countries: Examining the scale of the problem and the importance of context. Bull World Health Organ. 2007, 85 (10): 812-819.

Gabrysch S, Campbell O: Still too far to walk: Literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009, 9 (1): 34-10.1186/1471-2393-9-34.

STROBE Statement: Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology.http://www.strobe-statement.org/index.php?id?=?strobe-home,

Ekirapa-Kiracho E, Waiswa P, Rahman MH, Makumbi F, Kiwanuka N, Okui O, Rutebemberwa E, Bua J, Mutebi A, Nalwadda G, Serwadda D, Pariyo GW, Peters DH: Increasing access to institutional deliveries using demand and supply side incentives: Early results from a quasi-experimental study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2011, 11 (Suppl 1): S11-10.1186/1472-698X-11-S1-S11.

Penfold S, Harrison E, Bell J, Fitzmaurice A: Evaluation of the delivery fee exemption policy in Ghana: Population estimates of changes in delivery service utilization in two regions. Ghana Med Jour. 2007, 41 (3): 100-109.

Stanton C, Blanc AK, Croft T, Choi Y: Skilled care at birth in the developing world: Progress to date and strategies for expanding coverage. J Biosoc Sci. 2007, 39 (1): 109-120. 10.1017/S0021932006001271.

Hondula DM, Rocklov J, Sankoh OA: Past, present, and future climate at select INDEPTH member Health and Demographic Surveillance Systems in Africa and Asia. Glob Health Action. 2012, 5: 74-86.

Ye Y, Wamukoya M, Ezeh A, Emina JB, Sankoh O: Health and demographic surveillance systems: A step towards full civil registration and vital statistics system in sub-Sahara Africa?. BMC Public Health. 2012, 12: 741-2458–12-741-

Houweling TA, Ronsmans C, Campbell OM, Kunst AE: Huge poor-rich inequalities in maternity care: An international comparative study of maternity and child care in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2007, 85 (10): 745-754.

Stephenson R, Baschieri A, Clements S, Hennink M, Madise N: Contextual influences on the use of health facilities for childbirth in Africa. Am J Public Health. 2006, 96 (1): 84-93. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057422.

Rockers PC, Wilson ML, Mbaruku G, Kruk ME: Source of antenatal care influences facility delivery in rural Tanzania: A population-based study. Matern Child Health J. 2009, 13 (6): 879-885. 10.1007/s10995-008-0412-7.

Addai I: Determinants of use of maternal-child health services in rural Ghana. J Biosoc Sci. 2000, 32 (1): 1-15.

Aremu O, Lawoko S, Dalal K: Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage, individual wealth status and patterns of delivery care utilization in Nigeria: A multilevel discrete choice analysis. Int J Womens Health. 2011, 3: 167-174.

Idris SH, Gwarzo UMD, Shehu AU: Determinants of place of delivery among women in a semi-urban settlement in Zaria, northern Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2006, 5 (2): 68-72.

Letamo G, Rakgoasi SD: Factors associated with non-use of maternal health services in Botswana. J Health Popul Nutr. 2003, 21 (1): 40-47.

Magadi MA, Agwanda AO, Obare FO: A comparative analysis of the use of maternal health services between teenagers and older mothers in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). Soc Sci Med. 2007, 64 (6): 1311-1325. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.004.

Mpembeni RN, Killewo JZ, Leshabari MT, Massawe SN, Jahn A, Mushi D, Mwakipa H: Use pattern of maternal health services and determinants of skilled care during delivery in Southern Tanzania: Implications for achievement of MDG-5 targets. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007, 7: 29-10.1186/1471-2393-7-29.

Mwaniki PK, Kabiru EW, Mbugua GG: Utilisation of antenatal and maternity services by mothers seeking child welfare services in Mbeere District, Eastern Province, Kenya. East Afr Med J. 2002, 79 (4): 184-187.

Kruk ME, Galea S, Prescott M, Freedman LP: Health care financing and utilization of maternal health services in developing countries. Health Policy Plan. 2007, 22 (5): 303-310. 10.1093/heapol/czm027.

Mulogo EM, Witte K, Bajunirwe F, Nabukera SK, Muchunguzi C, Batwala VK, Bagenda F, Farr C, Barry S: Birth plans and health facility based delivery in rural Uganda. East Afr Med J. 2006, 83 (3): 74-83.

Magadi M, Diamond I, Rodrigues RN: The determinants of delivery care in Kenya. Soc Biol. 2000, 47 (3–4): 164-188.

Kunst AE, Houweling T: A global picture of poor-rich differences in the utilization of delivery care. Stud Health Serv Organ Policy. 2001, 17: 293-311.

Bazant ES, Koenig MA, Fotso JC, Mills S: Women's use of private and government health facilities for childbirth in Nairobi's informal settlements. Stud Fam Plann. 2009, 40 (1): 39-50. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2009.00185.x.

Fotso JC, Ezeh A, Madise N, Ziraba A, Ogollah R: What does access to maternal care mean among the urban poor? Factors associated with use of appropriate maternal health services in the slum settlements of Nairobi, Kenya. Matern Child Health J. 2009, 13 (1): 130-137. 10.1007/s10995-008-0326-4.

Fotso JC, Ezeh A, Oronje R: Provision and use of maternal health services among urban poor women in Kenya: What do we know and what can we do?. J Urban Health. 2008, 85 (3): 428-442. 10.1007/s11524-008-9263-1.

Fotso JC, Ezeh AC, Essendi H: Maternal health in resource-poor urban settings: How does women's autonomy influence the utilization of obstetric care services?. Reprod Health. 2009, 6: 9-10.1186/1742-4755-6-9.

Ochako R, Fotso JC, Ikamari L, Khasakhala A: Utilization of maternal health services among young women in Kenya: Insights from the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey, 2003. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011, 11: 1-10.1186/1471-2393-11-1.

Ahmed S, Creanga AA, Gillespie DG, Tsui AO: Economic status, education and empowerment: Implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2010, 5 (6): e11190-10.1371/journal.pone.0011190.

Babalola S, Fatusi A: Determinants of use of maternal health services in Nigeria-looking beyond individual and household factors. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth. 2009, 9: 43-10.1186/1471-2393-9-43.

Galaa SZ, Daare K: Understanding barriers to maternal child health services utilization in northern Ghana. J Soc Dev Africa. 2008, 23 (2): 127-155.

Gyimah SO, Takyi BK, Addai I: Challenges to the reproductive-health needs of African women: On religion and maternal health utilization in Ghana. Soc Sci Med. 2006, 62 (12): 2930-2944. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.034.

Hounton S, Chapman G, Menten J, De Brouwere V, Ensor T, Sombie I, Meda N, Ronsmans C: Accessibility and utilisation of delivery care within a Skilled Care Initiative in rural Burkina Faso. Trop Med Int Health. 2008, 13 (Suppl 1): 44-52.

Kruk ME, Prescott MR, Galea S: Equity of skilled birth attendant utilization in developing countries: Financing and policy determinants. Am J Public Health. 2008, 98 (1): 142-147. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.104265.

McNamee P, Ternent L, Hussein J: Barriers in accessing maternal healthcare: Evidence from low-and middle-income countries. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2009, 9 (1): 41-10.1586/14737167.9.1.41.

Mekonnen Y, Mekonnen A: Factors influencing the use of maternal healthcare services in Ethiopia. J Health Popul Nutr. 2003, 21 (4): 374-382.

Nuwaha F, Amooti-Kaguna B: Predictors of home deliveries in Rakai District, Uganda. Af J Reproductive Health. 1999, 3 (2): 79-86. 10.2307/3583363.

Oguntunde O, Aina O, Ibrahim MS, Umar HS, Passano P: Antenatal care and skilled birth attendance in three communities in Kaduna State, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2010, 14 (3): 89-96.

Olusanya BO, Alakija OP, Inem VA: Non-uptake of facility-based maternity services in an inner-city community in Lagos, Nigeria: An observational study. J Biosoc Sci. 2010, 42 (3): 341-358. 10.1017/S0021932009990526.

Uzochukwu BS, Onwujekwe OE, Akpala CO: Community satisfaction with the quality of maternal and child health services in southeast Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 2004, 81 (6): 293-299.

van den Broek NR, White SA, Ntonya C, Ngwale M, Cullinan TR, Molyneux ME, Neilson JP: Reproductive health in rural Malawi: A population-based survey. BJOG. 2003, 110 (10): 902-908.

Wanjira C, Mwangi M, Mathenge E, Mbugua G, Ng'ang'a Z: Delivery practices and associated factors among mothers seeking child welfare services in selected health facilities in Nyandarua South District, Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2011, 11: 360-10.1186/1471-2458-11-360.

Woldemicael G: Do women with higher autonomy seek more maternal health care? Evidence from Eritrea and Ethiopia. Health Care Women Int. 2010, 31 (7): 599-620. 10.1080/07399331003599555.

Zere E, Oluwole D, Kirigia JM, Mwikisa CN, Mbeeli T: Inequities in skilled attendance at birth in Namibia: A decomposition analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011, 11: 34-10.1186/1471-2393-11-34.

Onah HE, Ikeako LC, Iloabachie GC: Factors associated with the use of maternity services in Enugu, southeastern Nigeria. Soc Sci Med. 2006, 63 (7): 1870-1878. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.019.

Akazili J, Doctor HV, Aboky L, Hodgson A, Phillips JF: Is there any relationship beween antenatal care and place of delivery? Findings from rural northern Ghana. Afr J Health Sciences. 2011, 18 (1–2): 62-73.

Spangler SA, Bloom SS: Use of biomedical obstetric care in rural Tanzania: The role of social and material inequalities. Soc Sci Med. 2010, 71 (4): 760-768. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.025.

De Allegri M, Ridde V, Louis VR, Sarker M, Tiendrebeogo J, Ye M, Muller O, Jahn A: Determinants of utilisation of maternal care services after the reduction of user fees: A case study from rural Burkina Faso. Health Policy. 2011, 99 (3): 210-218. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.10.010.

Hong R, Ayad M, Ngabo F: Being insured improves safe delivery practices in Rwanda. J Community Health. 2011, 36 (5): 779-784. 10.1007/s10900-011-9376-4.

Mbonye AK, Asimwe JB: Factors associated with skilled attendance at delivery in Uganda: Results from a national health facility survey. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2010, 22 (2): 249-255.

Adanu RM: Utilization of obstetric services in Ghana between 1999 and 2003. Afr J Reprod Health. 2010, 14 (3): 153-158.

Cronje HS, Joubert G, Chapman RD, de Winnaar B, Bam RH: Utilisation of maternity services by black women in rural and urban areas of the Orange Free State. S Afr Med J. 1995, 85 (8): 762-765.

Smith KV, Sulzbach S: Community-based health insurance and access to maternal health services: Evidence from three West African countries. Soc Sci Med. 2008, 66 (12): 2460-2473. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.044.

Montagu D, Yamey G, Visconti A, Harding A, Yoong J: Where do poor women in developing countries give birth? A multi-country analysis of demographic and health survey data. PLoS One. 2011, 6 (2): e17155-10.1371/journal.pone.0017155.

van den Heuvel OA, de Mey WG, Buddingh H, Bots ML: Use of maternal care in a rural area of Zimbabwe: A population-based study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999, 78 (10): 838-846. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.1999.781002.x.

Hodgkin D: Household characteristics affecting where mothers deliver in rural Kenya. Health Econ. 1996, 5 (4): 333-340. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(199607)5:4<333::AID-HEC202>3.0.CO;2-K.

Kruk ME, Rockers PC, Mbaruku G, Paczkowski MM, Galea S: Community and health system factors associated with facility delivery in rural Tanzania: A multilevel analysis. Health Policy. 2010, 97 (2–3): 209-216.

Danforth EJ, Kruk ME, Rockers PC, Mbaruku G, Galea S: Household decision-making about delivery in health facilities: Evidence from Tanzania. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009, 27 (5): 696-703.

Faye A, Niane M, Ba I: Home birth in women who have given birth at least once in a health facility: Contributory factors in a developing country. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011, 90 (11): 1239-1243. 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01163.x.

Ejembi CL, Atli-Muaza M, Chirdan O, Ezeh HO, Sheidu S: Utilization of maternal health services by rural Hausa women in Zaria environs, northern Nigeria: Has primary health care made a difference?. J of Comm Med and Prim Health Care. 2004, 16 (2): 47-54.

Gage AJ: Barriers to the utilization of maternal health care in rural Mali. Soc Sci Med. 2007, 65 (8): 1666-1682. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.06.001.

Mills S, Williams JE, Adjuik M, Hodgson A: Use of health professionals for delivery following the availability of free obstetric care in northern Ghana. Matern Child Health J. 2008, 12 (4): 509-518. 10.1007/s10995-007-0288-y.

Uyirwoth GP, Itsweng MD, Mpai S, Nchabeleng E, Nkoane H: Obstetrics service utilisation by the community in Lebowa, northern Transvaal. East Afr Med J. 1996, 73 (2): 91-94.

Kyomuhendo GB: Low use of rural maternity services in Uganda: Impact of women's status, traditional beliefs and limited resources. Reprod Health Matters. 2003, 11 (21): 16-26. 10.1016/S0968-8080(03)02176-1.

Telfer ML, Rowley JT, Walraven GE: Experiences of mothers with antenatal, delivery and postpartum care in rural Gambia. Afr J Reprod Health. 2002, 6 (1): 74-83. 10.2307/3583148.

Gabrysch S, Cousens S, Cox J, Campbell OM: The influence of distance and level of care on delivery place in rural Zambia: A study of linked national data in a geographic information system. PLoS Med / Public Libr Sc. 2011, 8 (1): e1000394-

Tann CJ, Kizza M, Morison L, Mabey D, Muwanga M, Grosskurth H, Elliott AM: Use of antenatal services and delivery care in Entebbe, Uganda: A community survey. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth. 2007, 7: 23-10.1186/1471-2393-7-23.

Osubor KM, Fatusi AO, Chiwuzie JC: Maternal health-seeking behavior and associated factors in a rural Nigerian community. Matern Child Health J. 2006, 10 (2): 159-169. 10.1007/s10995-005-0037-z.

Kruk ME, Paczkowski M, Mbaruku G, de Pinho H, Galea S: Women's preferences for place of delivery in rural Tanzania: A population-based discrete choice experiment. Am J Public Health. 2009, 99 (9): 1666-1672. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.146209.

Bellows NM, Bellows BW, Warren C: Systematic Review: The use of vouchers for reproductive health services in developing countries: Systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2011, 16 (1): 84-96. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02667.x.

Arur A, Gitonga N, O'Hanlon B, Kundu F, Senkaali M, Ssemujju R: Insights from innovations: Lessons from designing and implementing family planning / reproductive health voucher programs in Kenya and Uganda. 2009

Janisch CP, Albrecht M, Wolfschuetz A, Kundu F, Klein S: Vouchers for health: A demand side output-based aid approach to reproductive health services in Kenya. Glob Public Health. 2010, 5 (6): 578-594. 10.1080/17441690903436573.

Erulkar AS, Ettyang LI, Onoka C, Nyagah FK, Muyonga A: Behavior change evaluation of a culturally consistent reproductive health program for young Kenyans. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2004, 30 (2): 58-67.

Amooti-Kaguna B, Nuwaha F: Factors influencing choice of delivery sites in Rakai district of Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2000, 50 (2): 203-213.

Magoma M, Requejo J, Campbell OM, Cousens S, Filippi V: High ANC coverage and low skilled attendance in a rural Tanzanian district: A case for implementing a birth plan intervention. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010, 10: 13-10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00275-0.

Cotter K, Hawken M, Temmerman M: Low use of skilled attendants' delivery services in rural Kenya. J Health Popul Nutr. 2006, 24 (4): 467-471. 10.1186/1471-2393-10-13.

Martey JO: Utilization of maternal health services in Ejisu District?. West Afr J Med. 1995, 14 (1): 24-28.

Nilses C, Nystrom L, Munjanja S, Lindmark G: Self-reported reproductive outcome and implications in relation to use of care in women in rural Zimbabwe. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002, 81 (6): 508-515.

Wilkinson D, Cutts F, Ntuli N, Abdool Karim SS: Maternal and child health indicators in a rural South African health district. S Afr Med J. 1997, 87 (4): 456-459. 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810606.x.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Both author declares no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CM conceived of the idea, planned the study, and conducted all searches. CM and AM worked together to determine whether studies met inclusion criteria and then both authors independently assessed each selected article for quality. CM drafted the initial manuscript and AM participated in critical review and revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Moyer, C.A., Mustafa, A. Drivers and deterrents of facility delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reprod Health 10, 40 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-10-40

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-10-40