Abstract

Background

Hypertension and chronic kidney disease (CKD) pose significant public health challenges, sharing intertwined pathophysiological mechanisms. Prediabetes is recognized as a precursor to diabetes and is often accompanied by cardiovascular comorbidities such as hypertension, elevating the risk of pre-frailty and frailty. Albuminuria is a hallmark of organ damage in hypertension amplifying the risk of pre-frailty, frailty, and cognitive decline in older adults. We explored the association between albuminuria and cognitive impairment in frail older adults with prediabetes and CKD, assessing cognitive levels based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

Methods

We conducted a study involving consecutive frail older patients with hypertension recruited from March 2021 to March 2023 at the ASL (local health unit of the Italian Ministry of Health) of Avellino, Italy, followed up after three months. Inclusion criteria comprised age over 65 years, prior diagnosis of hypertension without secondary causes, prediabetes, frailty status, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score < 26, and CKD with eGFR > 15 ml/min.

Results

237 patients completed the study. We examined the association between albuminuria and MoCA Score, revealing a significant inverse correlation (r: 0.8846; p < 0.0001). Subsequently, we compared MoCA Score based on eGFR, observing a significant difference (p < 0.0001). These findings were further supported by a multivariable regression analysis, with albuminuria as the dependent variable.

Conclusions

Our study represents the pioneering effort to establish a significant correlation between albuminuria and eGFR with cognitive function in frail hypertensive older adults afflicted with prediabetes and CKD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hypertension and chronic kidney disease (CKD) pose significant public health challenges, sharing intertwined pathophysiological mechanisms [1,2,3]. Elevated blood pressure contributes to kidney function decline, while CKD exacerbates hypertension [1, 4, 5]. Both conditions are associated with aging and frailty, contributing to adverse outcomes such as cognitive and physical impairments, driving the onset of disability, hospitalization, and death [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Frailty is an increasingly prevalent condition in older adults and is defined by the presence of at least three of five Fried criteria [13]; on the other hand, pre-frailty is a condition that precedes frailty defined by the presence of one or two Fried criteria [13]. Prediabetes is recognized as a precursor to diabetes, diagnosed with HbA1c values between 5.7 and 6.4% [14, 15], and is often accompanied by cardiovascular comorbidities, such as hypertension, thereby elevating the risk of pre-frailty and frailty [16, 17].

Albuminuria serves as a hallmark of kidney disease, subclinical cardiovascular issues, and organ damage in hypertension [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] amplifying the risk of pre-frailty, frailty, and cognitive decline in older adults [28,29,30,31,32,33]. Moreover, albuminuria may underlie endothelial dysfunction, prevalent in both hypertension and CKD [33,34,35,36,37]. Hence, in the present study we explored the association between albuminuria and cognitive impairment in frail older adults with prediabetes and CKD, assessing cognitive levels based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

Methods

We designed a study involving consecutive frail older patients with hypertension and prediabetes recruited from March 2021 to March 2023 at the ASL (local health unit of the Italian Ministry of Health) of Avellino, Italy. The study was named “CARYATID”: Cognitive performAnce fRail hYpertensive AdulTs wIth ckD. Inclusion criteria comprised age over 65 years, prior diagnosis of hypertension without secondary causes, prediabetes, frailty status, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score < 26 [38], and CKD with eGFR > 15 ml/min. Albuminuria was defined using a cutoff of 30 mg/dl in 24-hour urine [39]. Informed consent was obtained from each patient or their legal representative, and the research adhered to the principles outlined in the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent revisions. The Institutional Review Board of Campania Nord approved the protocol.

Global cognitive function evaluation

Global cognitive function has been assessed via MoCA test. This cognitive test covers many cognitive skills, and scores range from 0 to 30 and cognitive impairment is defined from values < 26 [38, 40].

Frailty assessment

A physical frailty assessment was performed following the Fried Criteria at baseline; a diagnosis of frailty status was performed with at least three points out of five criteria: low physical activity level, weight loss, exhaustion, weakness, slowness [13, 41].

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD or percentages. We correlated albuminuria with MoCA Score and gait speed. Afterwards, we compared global cognitive performance whether the eGFR was < 60 or > 60. The correlation between MoCA score and albuminuria was evaluated using the Spearman’s rank test. We also performed a multivariable regression analysis with albuminuria as the dependent variable adjusting for potential confounding factors. All calculations were computed using the SPSS 26 software.

Results

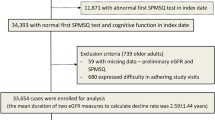

We assessed 334 frail hypertensive elders with prediabetes and CKD. Among them, 61 did not meet the inclusion criteria and 36 declined to participate, leaving 237 patients in our database; the flow-chart of the study is depicted in Fig. 1. The baseline characteristics of our population are shown in Table 1.

First, we examined the correlation between albuminuria and MoCA Score, revealing a statistically significant result (r: 0.8846; 95%CI: -0.9114 to -0.8505; p < 0.0001; Fig. 2).

Subsequently, we sought to assess if there was any difference in the values of MoCA Score when subdividing our population in two groups, based on their eGFR and we observed that the MoCA score was significantly reduced in patients with eGFR ≤ 60 vs. patients with eGFR > 60 (p < 0.0001; Fig. 3).

These findings were further supported by a multivariable regression analysis, with albuminuria as the dependent variable, as shown in Table 2.

Discussion

We conducted a comprehensive analysis to investigate the relationship between albuminuria, a marker of kidney damage, and the MoCA Score, a measure of cognitive function. Our results revealed a robust and statistically significant correlation between albuminuria and MoCA Score, indicating that higher levels of albumin in the urine were associated with lower cognitive performance. Additionally, we sought to explore the impact of eGFR on MoCA Score and found a significant difference in cognitive function based on eGFR levels, further highlighting the importance of kidney function in cognitive health. To validate these findings, we performed a multivariable regression analysis, with albuminuria as the dependent variable, which confirmed the significant association between albuminuria and cognitive impairment even after adjusting for potential confounding factors. Intriguingly, age was significant (p < 0.001), confirming the importance of aging in cognitive decline and frailty [42, 43].

Our observations are consistent with previous reports indicating that CKD often complicates hypertension [2, 24, 44], and that, likewise, prediabetes exacerbates kidney dysfunction [45,46,47,48]. Besides, albuminuria serves as a common marker of organ damage and endothelial dysfunction [49, 50] and the relationship between cognitive dysfunction/impairment and albuminuria is widely accepted [51, 52].

Thus, the relationship between CKD and hypertension is bidirectional and complex; hypertension can contribute to the development and progression of CKD by placing increased pressure on the kidneys over time, leading to damage to the blood vessels in the kidneys and impairing their ability to filter waste products and excess fluids from the blood effectively; conversely, CKD can also exacerbate hypertension by causing changes in the body’s fluid and electrolyte balance, leading to elevated blood pressure levels [53, 54]. Equally important, prediabetes is known to exacerbate kidney dysfunction [55]. In this context, cognitive impairment represents a prevalent complication among these individuals, particularly in frail patients who face an increased risk of cognitive decline, with or without dementia [56, 57]. Consequently, albuminuria may serve as a prognostic indicator for poorer cognitive performance within this subgroup [58,59,60]. Notably, in our study, eGFR levels significantly influence overall cognitive function, with a cutoff of 60 indicating lower MoCA Scores (p < 0.0001).

Our clinical study does not allow to determine the exact mechanisms underlying the association between albuminuria and cognitive dysfunction. A possibility is that endothelial dysfunction could play a pivotal role in precipitating adverse outcomes in hypertension and prediabetes, contributing to functional decline in frail older adults. Indeed, albuminuria may denote endothelial dysfunction [35, 61, 62], a condition highly prevalent in both hypertension and CKD [33, 34, 36, 37, 63, 64]. We also speculate that CKD patients may have vascular brain damage, exacerbating cognitive decline. This hypothesis may be confirmed by our Fig. 3 in which lower levels of eGFR are suggesting a worst global cognitive function. Indeed, vascular risk factors are known to contribute to both vascular and Alzheimer’s dementia [65, 66]. Limitations of our study include not having adjusted for current medications and not having obtained from each patients the socio-economic status, which might have influenced cognitive function [67,68,69,70].

Taken together, our results underscore the intricate interplay between kidney function and cognitive health, indicating that early detection and management of kidney damage may play a crucial role in preserving cognitive function. Thus, managing blood pressure and glycemia becomes paramount in preventing organ damage and associated complications. While our findings are significant, further investigations with larger sample sizes are necessary to validate our results.

Conclusions

We demonstrated a significant correlation between albuminuria and cognitive dysfunction, also showing that the MoCA score is significantly reduced in patients with eGFR ≤ 60 compared to patients with eGFR > 60, a finding corroborated by a multivariable regression analysis, adjusting for potential confounders. Our study represents the pioneering effort to establish a significant correlation between albuminuria and eGFR with cognitive function in frail hypertensive older adults afflicted with prediabetes and CKD.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the last author upon reasonable request.

Change history

29 May 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-024-02262-7

References

Ku E, Lee BJ, Wei J, Weir MR. Hypertension in CKD: Core Curriculum 2019. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;74(1):120–31.

Barcellos FC, Del Vecchio FB, Reges A, Mielke G, Santos IS, Umpierre D, Bohlke M, Hallal PC. Exercise in patients with hypertension and chronic kidney disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Hum Hypertens. 2018;32(6):397–407.

Dasgupta I, Zoccali C. Is the KDIGO systolic blood pressure target < 120 mm hg for chronic kidney Disease Appropriate in Routine Clinical Practice? Hypertension. 2022;79(1):4–11.

Kalaitzidis RG, Elisaf MS. Treatment of hypertension in chronic kidney disease. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20(8):64.

Wilson S, Mone P, Jankauskas SS, Gambardella J, Santulli G. Chronic kidney disease: definition, updated epidemiology, staging, and mechanisms of increased cardiovascular risk. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2021;23(4):831–4.

Benetos A, Petrovic M, Strandberg T. Hypertension management in older and Frail older patients. Circ Res. 2019;124(7):1045–60.

Yuan Y, Chen S, Lin C, Huang X, Lin S, Huang F, Zhu P. Association of triglyceride-glucose index trajectory and frailty in urban older residents: evidence from the 10-year follow-up in a cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22(1):264.

Richter D, Guasti L, Walker D, Lambrinou E, Lionis C, Abreu A, Savelieva I, Fumagalli S, Bo M, Rocca B, et al. Frailty in cardiology: definition, assessment and clinical implications for general cardiology. A consensus document of the Council for Cardiology Practice (CCP), Association for Acute Cardio Vascular Care (ACVC), Association of Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions (ACNAP), European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC), European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), Council on Valvular Heart diseases (VHD), Council on Hypertension (CHT), Council of Cardio-Oncology (CCO), Working Group (WG) Aorta and Peripheral Vascular diseases, WG e-Cardiology, WG thrombosis, of the European Society of Cardiology, European Primary Care Cardiology Society (EPCCS). Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022;29(1):216–27.

Mone P, Pansini A, Frullone S, de Donato A, Buonincontri V, De Blasiis P, Marro A, Morgante M, De Luca A, Santulli G. Physical decline and cognitive impairment in frail hypertensive elders during COVID-19. Eur J Intern Med. 2022;99:89–92.

Pansini A, Lombardi A, Morgante M, Frullone S, Marro A, Rizzo M, Martinelli G, Boccalone E, De Luca A, Santulli G, et al. Hyperglycemia and physical impairment in Frail Hypertensive older adults. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:831556.

Potok OA, Ix JH, Shlipak MG, Katz R, Hawfield AT, Rocco MV, Ambrosius WT, Cho ME, Pajewski NM, Rastogi A, et al. The difference between cystatin C- and creatinine-based estimated GFR and associations with Frailty and adverse outcomes: a cohort analysis of the systolic blood pressure intervention trial (SPRINT). Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76(6):765–74.

Mone P, Martinelli G, Lucariello A, Leo AL, Marro A, De Gennaro S, Marzocco S, Moriello D, Frullone S, Cobellis L, et al. Extended-release metformin improves cognitive impairment in frail older women with hypertension and diabetes: preliminary results from the LEOPARDESS Study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22(1):94.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–156.

American Diabetes Association Professional Practice C: 2. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes: standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(Suppl 1):S20–42.

Shi Y, Wen M. Sex-specific differences in the effect of the atherogenic index of plasma on prediabetes and diabetes in the NHANES 2011–2018 population. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22(1):19.

Mone P, De Gennaro S, Frullone S, Marro A, Santulli G. Hyperglycemia drives the transition from pre-frailty to frailty: the monteforte study. Eur J Intern Med. 2023;111:135–7.

Ostgren CJ, Otten J, Festin K, Angeras O, Bergstrom G, Cederlund K, Engstrom G, Eriksson MJ, Eriksson M, Fall T, et al. Prevalence of atherosclerosis in individuals with prediabetes and diabetes compared to normoglycaemic individuals-a Swedish population-based study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22(1):261.

Potier L, Chequer R, Roussel R, Mohammedi K, Sismail S, Hartemann A, Amouyal C, Marre M, Le Guludec D, Hyafil F. Relationship between cardiac microvascular dysfunction measured with 82Rubidium-PET and albuminuria in patients with diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):11.

Bikbov B, Soler MJ, Pesic V, Capasso G, Unwin R, Endres M, Remuzzi G, Perico N, Gansevoort R, Mattace-Raso F, et al. Albuminuria as a risk factor for mild cognitive impairment and dementia-what is the evidence? Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2021;37(Suppl 2):ii55–62.

Li M, Zhao Z, Qin G, Chen L, Lu J, Huo Y, Chen L, Zeng T, Xu M, Chen Y, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolic goal achievement with incident cardiovascular disease and eGFR-based chronic kidney disease in patients with prediabetes and diabetes. Metabolism. 2021;124:154874.

Papademetriou V, Nylen ES, Doumas M, Probstfield J, Mann JFE, Gilbert RE, Gerstein HC. Chronic kidney disease, Basal Insulin Glargine, and Health outcomes in people with Dysglycemia: the ORIGIN study. Am J Med. 2017;130(12):1465. e1427-1465 e1439.

Kinguchi S, Wakui H, Ito Y, Kondo Y, Azushima K, Osada U, Yamakawa T, Iwamoto T, Yutoh J, Misumi T, et al. Improved home BP profile with dapagliflozin is associated with amelioration of albuminuria in Japanese patients with diabetic nephropathy: the Yokohama add-on inhibitory efficacy of dapagliflozin on albuminuria in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes study (Y-AIDA study). Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):110.

Vassalotti JA, Centor R, Turner BJ, Greer RC, Choi M, Sequist TD. National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality I: practical Approach to detection and management of chronic kidney disease for the Primary Care Clinician. Am J Med. 2016;129(2):153–62. e157.

Horowitz B, Miskulin D, Zager P. Epidemiology of hypertension in CKD. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015;22(2):88–95.

Yang X, Ma RC, So WY, Ko GT, Kong AP, Lam CW, Ho CS, Cockram CS, Wong VC, Tong PC, et al. Impacts of chronic kidney disease and albuminuria on associations between coronary heart disease and its traditional risk factors in type 2 diabetic patients - the Hong Kong diabetes registry. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2007;6:37.

Agarwal R. Albuminuria and masked uncontrolled hypertension in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2017;32(12):2058–65.

Kim SR, Lee YH, Lee SG, Kang ES, Cha BS, Lee BW. The renal tubular damage marker urinary N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase may be more closely associated with early detection of atherosclerosis than the glomerular damage marker albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):16.

Schechter M, Melzer Cohen C, Fishkin A, Rozenberg A, Yanuv I, Sehtman-Shachar DR, Chodick G, Clark A, Abrahamsen TJ, Lawson J, et al. Kidney function loss and albuminuria progression with GLP-1 receptor agonists versus basal insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes: real-world evidence. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22(1):126.

Mielke N, Schneider A, Barghouth MH, Ebert N, van der Giet M, Huscher D, Kuhlmann MK, Schaeffner E. Association of kidney function and albuminuria with frailty worsening and death in very old adults. Age Ageing 2023, 52(5).

Miller LM, Rifkin D, Lee AK, Kurella Tamura M, Pajewski NM, Weiner DE, Al-Rousan T, Shlipak M, Ix JH. Association of Urine Biomarkers of Kidney Tubule Injury and Dysfunction with Frailty Index and cognitive function in persons with CKD in SPRINT. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;78(4):530–e540531.

Zhang H, Hao M, Li Y, Jiang X, Wang M, Chen J, Wang X, Sun X. Glomerular filtration rate by different measures and albuminuria are associated with risk of frailty: the Rugao Longitudinal Ageing Study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;34(11):2703–11.

Liu M, He P, Zhou C, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Li H, Liu C, Nie J, Liang M, Qin X. Association of urinary albumin:creatinine ratio with incident frailty in older populations. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15(6):1093–9.

Yang X, Jiang Y, Li J, Yang M, Liu Y, Dong B, Li Y. Association between Frailty and Albuminuria among older Chinese inpatients. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(2):197–200.

Mone P, Pansini A, Calabro F, De Gennaro S, Esposito M, Rinaldi P, Colin A, Minicucci F, Coppola A, Frullone S, et al. Global cognitive function correlates with P-wave dispersion in frail hypertensive older adults. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2022;24(5):638–43.

Sasso FC, Simeon V, Galiero R, Caturano A, De Nicola L, Chiodini P, Rinaldi L, Salvatore T, Lettieri M, Nevola R, et al. The number of risk factors not at target is associated with cardiovascular risk in a type 2 diabetic population with albuminuria in primary cardiovascular prevention. Post-hoc analysis of the NID-2 trial. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21(1):235.

Seliger SL, Salimi S, Pierre V, Giffuni J, Katzel L, Parsa A. Microvascular endothelial dysfunction is associated with albuminuria and CKD in older adults. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17(1):82.

Theodorakopoulou MP, Dipla K, Zafeiridis A, Sarafidis P. Epsilonndothelial and microvascular function in CKD: evaluation methods and associations with outcomes. Eur J Clin Invest. 2021;51(8):e13557.

Mone P, Gambardella J, Lombardi A, Pansini A, De Gennaro S, Leo AL, Famiglietti M, Marro A, Morgante M, Frullone S, et al. Correlation of physical and cognitive impairment in diabetic and hypertensive frail older adults. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21(1):10.

Shlipak MG, Tummalapalli SL, Boulware LE, Grams ME, Ix JH, Jha V, Kengne AP, Madero M, Mihaylova B, Tangri N, et al. The case for early identification and intervention of chronic kidney disease: conclusions from a kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2021;99(1):34–47.

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–9.

Mone P, Gambardella J, Pansini A, Martinelli G, Minicucci F, Mauro C, Santulli G. Cognitive dysfunction correlates with physical impairment in frail patients with acute myocardial infarction. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;34(1):49–53.

Mone P, De Luca A, Santulli G. Editorial: Frailty and oxidative stress. Front Aging. 2023;4:1345486.

Mone P, Guerra G, Lombardi A, Illario M, Pansini A, Marro A, Frullone S, Taurino A, Sorriento D, Verri V, et al. Effects of SGLT2 inhibition via empagliflozin on cognitive and physical impairment in frail diabetic elders with chronic kidney disease. Pharmacol Res. 2024;200:107055.

Judd E, Calhoun DA. Management of hypertension in CKD: beyond the guidelines. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015;22(2):116–22.

Lamprou S, Koletsos N, Mintziori G, Anyfanti P, Trakatelli C, Kotsis V, Gkaliagkousi E, Triantafyllou A. Microvascular and endothelial dysfunction in Prediabetes. Life (Basel) 2023, 13(3).

Tabak AG, Herder C, Rathmann W, Brunner EJ, Kivimaki M. Prediabetes: a high-risk state for diabetes development. Lancet. 2012;379(9833):2279–90.

Chen C, Liu G, Yu X, Yu Y, Liu G. Association between prediabetes and Renal Dysfunction from a community-based prospective study. Int J Med Sci. 2020;17(11):1515–21.

Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Narayan KM, Weisman D, Golden SH, Jaar BG. Association between prediabetes and risk of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2016;33(12):1615–24.

Ochodnicky P, Henning RH, van Dokkum RP, de Zeeuw D. Microalbuminuria and endothelial dysfunction: emerging targets for primary prevention of end-organ damage. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2006;47(Suppl 2):S151–162. discussion S172-156.

Ruilope L, Izzo J, Haller H, Waeber B, Oparil S, Weber M, Bakris G, Sowers J. Prevention of microalbuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes: what do we know? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12(6):422–30.

Georgakis MK, Dimitriou NG, Karalexi MA, Mihas C, Nasothimiou EG, Tousoulis D, Tsivgoulis G, Petridou ET. Albuminuria in Association with cognitive function and dementia: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(6):1190–8.

Li H, Zhao S, Wang R, Gao B. The association between cognitive impairment/dementia and albuminuria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2022;26(1):45–53.

Burnier M, Damianaki A. Hypertension as Cardiovascular Risk factor in chronic kidney disease. Circ Res. 2023;132(8):1050–63.

Blin P, Joubert M, Jourdain P, Zaoui P, Guiard E, Sakr D, Dureau-Pournin C, Bernard MA, Lassalle R, Thomas-Delecourt F, et al. Cardiovascular and renal diseases in type 2 diabetes patients: 5-year cumulative incidence of the first occurred manifestation and hospitalization cost: a cohort within the French SNDS nationwide claims database. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23(1):22.

Kim GS, Oh HH, Kim SH, Kim BO, Byun YS. Association between prediabetes (defined by HbA1(C), fasting plasma glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance) and the development of chronic kidney disease: a 9-year prospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20(1):130.

Uchmanowicz I, Rosano G, Francesco Piepoli M, Vellone E, Czapla M, Lisiak M, Diakowska D, Prokopowicz A, Aleksandrowicz K, Nowak B, et al. The concurrent impact of mild cognitive impairment and frailty syndrome in heart failure. Arch Med Sci. 2023;19(4):912–20.

Searle SD, Rockwood K. Frailty and the risk of cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7(1):54.

Martens RJ, Kooman JP, Stehouwer CD, Dagnelie PC, van der Kallen CJ, Koster A, Kroon AA, Leunissen KM, Nijpels G, van der Sande FM, et al. Estimated GFR, Albuminuria, and cognitive performance: the Maastricht Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69(2):179–91.

Elias MF, Torres RV, Davey A. Albuminuria and Cognitive Performance: New evidence for consideration of a risk factor Precursor Model from the Maastricht Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69(2):163–5.

Zhang J, Zhang A. Relationships between serum Klotho concentrations and cognitive performance among older chronic kidney disease patients with albuminuria in NHANES 2011–2014. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1215977.

Gonzalez-Blazquez R, Somoza B, Gil-Ortega M, Martin Ramos M, Ramiro-Cortijo D, Vega-Martin E, Schulz A, Ruilope LM, Kolkhof P, Kreutz R, et al. Finerenone attenuates endothelial dysfunction and Albuminuria in a chronic kidney Disease Model by a reduction in oxidative stress. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1131.

Gerstein HC, Mann JF, Yi Q, Zinman B, Dinneen SF, Hoogwerf B, Halle JP, Young J, Rashkow A, Joyce C, et al. Albuminuria and risk of cardiovascular events, death, and heart failure in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals. JAMA. 2001;286(4):421–6.

Mohammad Zadeh Gharabaghi MA, Rezvanfar MR, Saeedi N, Aghajani F, Alirezaei M, Yarahmadi P, Nakhostin-Ansari A. Comparison of effects of Empagliflozin and Linagliptin on renal function and glycaemic control: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;8(1):5.

Koo BK, Chung WY, Moon MK. Peripheral arterial endothelial dysfunction predicts future cardiovascular events in diabetic patients with albuminuria: a prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19(1):82.

Knopman DS, Roberts R. Vascular risk factors: imaging and neuropathologic correlates. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(3):699–709.

Gorelick PB. Risk factors for vascular dementia and Alzheimer disease. Stroke. 2004;35(11 Suppl 1):2620–2.

Chang J, Hou W, Li Y, Li S, Zhao K, Wang Y, Hou Y, Sun Q. Prevalence and associated factors of cognitive frailty in older patients with chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):681.

Ritte RE, Lawton P, Hughes JT, Barzi F, Brown A, Mills P, Hoy W, O’Dea K, Cass A, Maple-Brown L. Chronic kidney disease and socio-economic status: a cross sectional study. Ethn Health. 2020;25(1):93–109.

Gottesman RF, Schneider AL, Zhou Y, Coresh J, Green E, Gupta N, Knopman DS, Mintz A, Rahmim A, Sharrett AR, et al. Association between midlife vascular risk factors and estimated brain amyloid deposition. JAMA. 2017;317(14):1443–50.

Iadecola C, Gorelick PB. Converging pathogenic mechanisms in vascular and neurodegenerative dementia. Stroke. 2003;34(2):335–7.

Funding

The Santulli’s Laboratory is supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI: R01-HL146691, T32-HL144456) and National Institutes of Health (NIH): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK: R01-DK123259, R01-DK033823). This publication was produced with the co-funding European Union – Next Generation EU, in the context of The National Recovery and Resilience Plan, Investment Partenariato Esteso PE8 “Conseguenze e sfide dell’invecchiamento”, Project Age-It (Ageing Well in an Ageing Society).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.S. and P.M. conceived the project and wrote the manuscript; V.Vi, M.C., M.V.N.F, P.M, A.Pa., N.V., A.Pi., G.G., V.Ve, G.M. A.T., and K.K. performed research and/or analyzed data. All authors approved the submission of this article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Prof G. Santulli is a co-author of this study and an Associate Editor of the Journal. He was not involved in handling this manuscript during the submission and the review processes. The rest of the authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: The error in the corresponding authorship has been corrected along with the affiliation corrections

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Santulli, G., Visco, V., Ciccarelli, M. et al. Frail hypertensive older adults with prediabetes and chronic kidney disease: insights on organ damage and cognitive performance - preliminary results from the CARYATID study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 23, 125 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-024-02218-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-024-02218-x