Abstract

Background

To investigate the difference of right ventricular (RV) structural and functional alteration in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and the ventricular interdependence in these patients, using cardiac MR (CMR) feature tracking.

Methods

From December 2016 to February 2022, 148 clinically diagnosed patients with DM who underwent cardiac MR (CMR) in our hospital were consecutively recruited. Fifty-four healthy individuals were included as normal controls. Biventricular strains, including left/right ventricular global longitudinal strain (LV-/RVGLS), left/right ventricular global circumferential strain (LV-/RVGCS), left/right ventricular global radial strain (LV-/RVGRS) were evaluated, and compared between patients with DM and healthy controls. Multiple linear regression and mediation analyses were used to evaluate DM's direct and indirect effects on RV strains.

Results

No differences were found in age (56.98 ± 10.98 vs. 57.37 ± 8.41, p = 0.985), sex (53.4% vs. 48.1%, p = 0.715), and body surface area (BSA) (1.70 ± 0.21 vs. 1.69 ± 0.17, p = 0.472) between DM and normal controls. Patients with DM had decreased RVGLS (− 21.86 ± 4.14 vs. − 24.49 ± 4.47, p = 0.001), RVGCS (− 13.16 ± 3.86 vs. − 14.92 ± 3.08, p = 0.011), and no decrease was found in RVGRS (22.62 ± 8.11 vs. 23.15 ± 9.05, p = 0.743) in patients with DM compared with normal controls. The difference in RVGLS between normal controls and patients with DM was totally mediated by LVGLS (indirect effecting: 0.655, bootstrapped 95%CI 0.138–0.265). The difference in RVGCS between normal controls and DM was partly mediated by the LVGLS (indirect effecting: 0.336, bootstrapped 95%CI 0.002–0.820) and LVGCS (indirect effecting: 0.368, bootstrapped 95%CI 0.028–0.855).

Conclusions

In the patients with DM and preserved LVEF, the difference in RVGLS between DM and normal controls was totally mediated by LVGLS. Although there were partly mediating effects of LVGLS and LVGCS, the decrease in RVGCS might be directly affected by the DM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is one of the most important diabetes-related complications [1,2,3]. Rubler et al. identified diffused myocardial fibrosis, cardiac hypertrophy, and myocardial microangiopathy in diabetes patients and termed it diabetic cardiomyopathy [4]. Latest guidelines and the majority of studies have so far described diabetic cardiomyopathy as a disease involving the left ventricular (LV) [5,6,7]. It is generally accepted that diabetic cardiomyopathy presents early with left ventricular hypertrophy, increased cardiac stiffness, and impaired diastolic function and later develops into heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, which can lead to serious cardiovascular-related death [8, 9]. With the intensive study of diabetic cardiomyopathy, it has become apparent that diabetic cardiomyopathy is not a regional disease of the left ventricle but may also have a parallel effect on the right ventricular (RV) through a similar pathological process [10, 11]. It is noteworthy that the interdependence of biventricular function in diabetic cardiomyopathy cannot be ignored. Dysfunction of the left ventricular leads to reduced right ventricular function via mechanical interaction of the septal wall or pericardium [12,13,14]. Small studies suggest that right ventricular dysfunction may be associated with a poor prognosis for long-term cardiovascular disease [15]. Diabetes-related right ventricle dysfunction and biventricular interactions are often overlooked and, to date, remain largely unexplored.

Due to the high temporal and soft tissue resolution, CMR imaging is considered the gold standard for assessing myocardial structure and function [16]. Novel CMR postprocessing tool, such as CMR feature tracking (CMR-FT), significantly improves RV functional assessment [17, 18]. Given these considerations, we design the present study to investigate the right ventricular structural and functional characteristics in diabetic patients with preserved LV ejection fraction (LVEF) and the mediating effects of LV dysfunction on RV strain in these patients, using CMR-FT.

Methods

Study population

The Institutional Review Board approved this study, and informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this investigation. From December 2016 to February 2022, clinically diagnosed patients with DM who underwent cardiac MR in our hospital were consecutively recruited. The inclusion criteria were:1) DM diagnosed according to the guidelines of the American Diabetes Association [19] or patients receiving glucose-lowering therapy. 2) patients with preserved LVEF on CMR (> 50%).The exclusion criteria were: (1) known cardiovascular disease, including coronary heart disease (myocardial infarction, revascularization, or coronary bypass), primary cardiomyopathy, severe valvular heart disease, congenital heart disease, and so on; (2)patients with diseases that may affect right heart function, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary artery embolism, and clinically diagnosed pulmonary hypertension; (3) incomplete critical clinical information; and (4) poor image quality cannot be used for analysis. A total of 148 patients with DM were finally recruited in this study. Fifty-four healthy individuals were included as normal controls.

Patient's demographic characteristics, clinical history, cardiovascular risk factors, and laboratory test results were recorded through Hospital Information System and Laboratory Information Management System.

Cardiac MRI scan protocol

Cardiac MR scanning was performed using a whole-body 3.0 T Siemens MAGNETOM Trio Tim system or a MAGNETOM Skyra scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). The balanced steady-state free precession cine images were obtained in standard short- and long-axis views at end-expiratory breath-hold. The parameters for the Siemens MAGNETOM Trio Tim system were: temporal resolution,40.35 ms; repetition time/echo time, 3.4/1.3 ms; matrix, 208 × 139; flip angle, 50◦; field of view, 250 mm × 300 mm; slice thickness, 8 mm; and the number of frames, 25 per cardiac cycle. The parameters for the MAGNETOM Skyra scanner were: temporal resolution, 39.34 ms; repetition time/ echo time 2.8/1.2 ms; flip angle, 38◦; slice thickness, 8 mm; the field of view, 360 mm × 300 mm; matrix size, 256 × 166; and the number of frames, 25 per cardiac cycle.

Cardiac function and feature tracking analysis

All the CMR images were independently analyzed by two radiologists with more than three years of experience in CMR diagnosis using commercial software (cvi42, Circle Cardiovascular Imaging, Calgary, Canada). To calculate bi-ventricular functional parameters, including RV-/LV end-systolic volume (RV/LV ESV), RV/LV end-diastolic volume (RV/LV EDV), myocardial mass, and RV/LV ejection fraction (RV/LVEF), ventricular epi- and endocardial borders were traced in contiguous short-axis images on end-systole and end-diastole. RV/LV EDV, RV/LV ESV, and myocardial mass were standardized by body surface area (BSA). The RV/LV remodeling index (RV/LVRI) were calculated as the myocardial mass divided by the EDV. To analyze the biventricular feature tracking parameters, additional left ventricular four- and two-chamber longitudinal views and right ventricular four-chamber longitudinal views were tracked with the end-diastole set as the reference point. 3D LV strain parameters (LV global longitudinal strain (LVGLS), LV global radial strain (LVGRS), and LV global circumferential strain (LVGCS)) and 2D RV strain parameters (RV global longitudinal strain (RVGLS), RV global radial strain (RVGRS), and RV global circumferential strain (RVGCS)) were automatically generated after these contours tracing performed (Fig. 1).

Illustration of the color-coded 2D strain for the right ventricle of a DM patient. After right ventricular epi- and endocardial borders were traced in short-axis and 4ch- longitudinal view images on end-systole (a2–c2) and end-diastole (a1–c1), RVGCS (a3), RVGRS (b3), and RVGLS (c3) were automatically generated. ED, end-diastolic; ES, end-systolic; RVGCS, right ventricular global circumferential strain; RVGLS, right ventricular global longitudinal strain; RVGRS, right ventricular global radial strain

Reproducibility analysis

To determine intra- and inter-observer variability of biventricular CMR-FT parameters, 40 random subjects were measured twice by a radiologist at a 2-week interval. Another investigator reanalyzed the measurement results of the software (cvi42). The twice measurement results of the first investigators were used to assess intra-observer variability. The measurement results of the two investigators were used to assess inter-observer variability.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range. The difference between normal controls and patients with DM was tested with the Mann–Whitney U test or independent t-test. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage, and differences between groups were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Relationships between RV strain and LV geometric parameters and strains (LVGLS, LVGCS, and LVGRS) were estimated with Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficient analysis, as appropriate.

Multivariate linear regression models adjusting for statistically significant parameters in univariate analysis (p < 0.05) and traditional clinical risk factors (age, sex, BSA, smoking history, drinking history, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia) were constructed to determine the independent effects of DM on the biventricular strains. Multicollinearity was assessed by the variance inflation factor (VIF > 10). Mediation analyses with bootstrap method were performed to assess whether ventricular interdependence statistically mediated the RV strain difference between diabetes and normal controls [20]. LV strains independently affected by diabetes (LVGLS and LVGCS) were added into the aforementioned regression models as mediators. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were used to assess intra- and inter-observer variability of 3D LV and 2D RV strain parameters. The significance level of all analyses was set at two-side p < 0.05. The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Clinical characteristics of patients with DM

The final analysis included 148 patients with DM and preserved LVEF and 54 normal controls. The mean age of patients with DM was 56.98 ± 10.98 years, and 91 (61.5%) had hypertension. No differences were found in age (56.98 ± 10.98 vs. 57.37 ± 8.41, p = 0.985), sex (53.4% vs. 48.8%, p = 0.472), and BSA (1.70 ± 0.21 vs. 1.69 ± 0.17, p = 0.715) between DM and normal controls. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the research subjects are summarized in Table 1.

Characteristics of biventricular structure and function in diabetic patients

Table 2 shows the biventricular structural and functional characteristics of diabetic patients. Compared with normal controls, patients with DM had higher heart rate (HR, 78.50 ± 13.53 vs. 72.49 ± 11.23, p = 0.008) and showed increased LV mass index (LVMI) (50.61 ± 16.28 vs. 43.69 ± 8.92, p = 0.007) and LVRI (0.69 ± 0.18 vs. 0.60 ± 0.09, p = 0.004). No differences were found in LVEF (62.95 ± 6.98 vs. 64.04 ± 4.16, p = 0.097), LVEDVI (74.67 ± 17.62 vs. 73.12 ± 11.31, p = 0.294), and LVESVI (28.18 ± 10.21 vs. 26.47 ± 6.11, p = 0.078) between the two groups. No differences were found in RVEF (61.41 ± 8.04 vs. 60.47 ± 6.59, p = 0.549), RVEDVI (58.42 ± 15.52 vs. 58.70 ± 12.49, p = 0.778), RVESVI (22.71 ± 8.22 vs. 23.37 ± 7.13, p = 0.592), RVMI (14.08 ± 3.57 vs. 14.43 ± 3.22, p = 0.462), and RVRI (0.25 ± 0.05 vs. 0.25 ± 0.04, p = 0.866) between patients with DM and normal controls.

The comparison of biventricular strain between the DM and normal controls is shown in Fig. 2. Compared to normal controls, patients with DM had lower LVGLS (− 12.76 ± 3.09 vs. − 15.27 ± 2.42, p < 0.001) and LVGCS (− 19.95 ± 3.14 vs. − 21.88 ± 2.4, p = 0.001), and the LVGRS (34.67 ± 11.57 vs. 38.41 ± 8.51, p = 0.066) was not significant reduced. Compared to normal controls, patients with DM had decreased RVGLS (− 21.86 ± 4.14 vs. − 24.49 ± 4.47, p = 0.001) and RVGCS (− 13.16 ± 3.86 vs. − 14.92 ± 3.08, p = 0.011). No decrease was found in RVGRS (22.62 ± 8.11 vs. 23.15 ± 9.05, p = 0.743) in patients with DM compared with normal controls.

Comparing LV- and RV strains between patients with DM and normal control. LVGLS: left ventricular global longitudinal strain. LVGCS: left ventricular global circumferential strain. LVGRS: left ventricular global radial strain. NC: normal controls. DM: diabetic mellitus. Data are reported as median (25th–75th percentiles). *: p < 0.05 between DM and NC. **: p < 0.001 between DM and NC. NS: not significant

Correlation between RV strains and LV structure and function

RVGLS were significantly correlated with LVEF (r = − 0.258, p = 0.001), LVEDVI (r = 0.240, p = 0.002), LVESVI (r = 0.278, p < 0.001), LVRI (r = 0.161, p = 0.040), LVMI (r = 0.328, p < 0.001), LVGLS (r = 0.334, p < 0.001), LVGCS (r = 0.378, p < 0.001), and LVGRS (− 0.310, p < 0.001). RVGCS were significantly correlated with LVEF (r = − 0.281, p = 0.001), LVEDVI (r = 0.249, p = 0.008), LVESVI (r = 0.309, p < 0.001), LVMI (0.159, p = 0.043), LVGLS (r = 0.232, p = 0.009), LVGCS (r = 0.360, p < 0.001), and LVGRS (− 0.368, p < 0.001). RVGRS were significantly correlated with LVEF (r = 0.289, p < 0.001), LVEDVI (r = − 0.207, p = 0.009), LVESVI (r = − 0.294, p < 0.001), LVGCS (r = − 0.291, p < 0.001), LVGLS (r = − 0.173, p = 0.029), and LVGRS (r = 0.365, p < 0.001). No significant correlation was found between RVGRS and LVMI (r = − 0.084, p = 0.292) or LVRI (r = 0.101, p = 0.203) (Table 3).

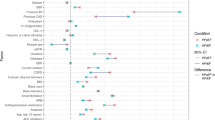

The impact of DM on biventricular structure and function

The multivariable analysis showed that after adjusting the confounding factors (including age, sex, BSA, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking, drinking, heart rate, HDL-C, LDL-C and FBG), DM was the independent impactor of LVGLS (0.249(0.500, 3.196), p = 0.008), LVGCS (0.250(0.470, 3.182), p = 0.009), RVGLS (2.087(0.134, 4.040), p = 0.036), RVGCS (3.351(1.1691, 5.012), < 0.001), but have no impact on LVRI (0.037(− 0.037,0.110), p = 0.328), LVMI (1.569(− 4.952, 8.090), p = 0.635). (Fig. 3).

Forest plot: Univariate and Multifactorial analysis of diabetes mellitus on biventricular structural and functional parameters. Abbreviations are consistent with Table 2 and Fig. 2. Multivariable analysis corrected for age, sex, body surface area, history of smoking, history of alcohol consumption, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, FBG, HDL-C, LDL-C, and heart rate

Direct and indirect effecting of DM on RV strains

Direct and indirect effects of DM on RV strains with mediators LVGLS and LVGCS are displayed in Table 4. The difference in RVGLS between normal controls and patients with DM was totally mediated by LVGLS (indirect effecting: 0.655, bootstrapped 95%CI 0.138–0.265), and LVGCS had no significant mediating effect. The difference in RVGCS between normal controls and patients with DM was partly mediated by the LVGLS (indirect effecting: 0.336, bootstrapped 95%CI 0.002–0.820) and LVGCS (indirect effecting: 0.368, bootstrapped 95%CI 0.028–0.855).

Intra- and Inter-observer Reproducibility

Intra- and inter-observer variabilities of biventricular strain are shown in Table 5. The intra- and inter-observer ICCs for RV strain were between 0.672–0.874 and 0.604–0.832, for LV strain were between 0.786–0.929 and 0.734–0.845.

Discussion

The present study investigated the RV structure and function difference between DM individuals with preserved LVEF and normal controls using CMR tissue-tracking techniques. Notwithstanding, ventricular interdependence via the septum cannot be ignored in the study of right ventricular dysfunction. We further explored the differences in RV function between DM and normal populations with LV strain as mediators. Our data revealed that RVGLS, RVGCS, LVGLS, and LVGCS were decreased in patients with DM compared with normal controls, and DM was an independent influence on the aforementioned biventricular strain. However, the difference in RVGLS between DM and normal controls was totally mediated by LVGLS. LVGLS and LVGCS partially mediated the difference in RVGCS between DM and normal controls.

Potential pathophysiological mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy

Cardiovascular disease is a common complication in patients with diabetes [8, 21]. A large number of scholars have conducted intensive research on diabetes-related cardiomyopathy. Nevertheless, the lack of a precise definition makes the study of diabetes-related cardiomyopathy pathophysiology, natural course, and associated clinical outcomes challenging. Important factors currently thought to drive the pathology of myocardial dysfunction in DM are insulin resistance/hyperinsulinemia and impaired glucose tolerance, which may be present years or more before the onset of DM. The GLP-1R is a highly effective target for managing type 2 diabetes by increasing insulin secretion, which lowers blood glucose levels. Enhanced glucose-stimulated GLP-1 responses may have positive impacts on vascular function, reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality, and lowering central and peripheral blood pressure [22]. Diabetic patients face an increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome, and in some cases, thoracic adipose tissue secretes higher levels of Cer16:0, which amplifies oxidative stress, systemic inflammation and reduces endothelium-dependent vasodilation, resulting in adverse cardiac outcomes [23]. The LV myocardial work is the main source of total cardiac work, and current studies on the pathogenesis and prognosis of diabetic cardiomyopathy focused on LV. At the early stage of diabetic cardiomyopathy onset, cardiac hypertrophy is associated with progressive impairment in LV strain and torsion, and abnormalities in left ventricular diastolic function are detected in about 75% of diabetic patients at this stage. These changes are accompanied by an upregulation of specific microRNAs targeting the extracellular matrix [24]. Extracellular volume (ECV) fraction-derived myocardial fibrosis was proven to be an independent risk factor of heart failure [25,26,27].

Imaging evaluation of right ventricular dysfunction in DM

Diabetes is a systemic disease, and it is reasonable to believe that the right ventricle suffers a parallel injury. As a convenient imaging modality, most of the findings of structural and functional alterations in the RV are based on the results of ultrasound studies. The narrow acoustic window, dependence on operator interpretation, and tracking errors due to the low signal-to-noise ratio limit the use of 2D-STE. The thinner wall of the RV increases the difficulty of assessment accurately and reproducibility of 2D-STE. Longitudinal strain based on 2D speckle tracking echocardiography is promoted as an approximate of RV myocardial work [28]. Several investigators reported reduced RVGLS in diabetic patients relative to normal subjects. They omitted RVGCS into observations, considering that RVGLS was a better parameter reflecting the RV contractility [29]. In recent years, cardiologists have focused on RV geometry and function alteration in different disease spectra using CMR, which has higher tissue resolution and reproducibility. Shao et al. studied characteristics of RV function in diabetic patients with preserved LV function using CMR feature-tracking and showed impaired RVGLS in these individuals [30]. We included the patients with DM and preserved LVEF as research subjects, and the same was found that these patients had decreased RVGLS compared with normal controls. Our study further showed good reproducibility in assessing RVGCS by cardiac MR feature tracking and found reduced RVGCS in diabetic patients.

Ventricular interdependence and the mediating effect of LV strain on RV dysfunction in patients with DM

Ventricular interdependence via the septum and limited pericardial flexibility is another possible mechanism for RV dysfunction in DC. It is theorized that LV contraction might be the primary source for RV-developed pressure, and about 20–40% of RV systolic pressure resulted from LV contraction [12]. The septum's motion and position are essential in ventricular interaction. Diffusion tensor magnetic resonance image elaborated the common myocardial fiber encircled the ventricle [31]. LV geometry and function alterations could contribute to RV dysfunction through ventricular interdependency mediated by the septum [13, 32]. LV myocardial function has been reported to be highly associated with RVGLS in diabetic patients [33,34,35,36]. The Maastricht Study found that LV structure or function indices did not statistically mediate the association between DM and RV structural changes [37].

Taken together, left ventricular strain impairment in DM is associated with RV function is well known. Whether the impact of DM on RV strains decrease is mediated by LV strains alteration remains uncertain. RV free-wall GLS decrease was totally mediated by LVGLS, whereas RVGCS impairment was partially mediated by LV function in diabetic patients with preserved LVEF. Our results were inconsistent with the study of Pauline et al. [37]. A possible explanation is a difference in the study population, as their study included patients with preserved LV function, whereas the patients with DM in our study showed significantly reduced LVGLS. This is broadly consistent with the previously proposed theory of biventricular interdependence, i.e., a weaker biventricular interaction in the presence of normal LV function [14].

Limitations

Despite the meaningful results, several limitations of the current study cannot be ignored. Firstly, it was a single-center, retrospective study, and there might be potential selection bias. Secondly, we included diabetic patients with preserved LVEF, and the generalizability of our findings to other populations can be questioned, and whether biventricular function maintains the same interactions in DM with heart failure is worth to be further explored. Thirdly, the characteristics of retrospective studies limited our ability to consider the duration of diabetes diagnosis, it is crucial for future studies to investigate whether this variable has an impact on the changes in biventricular structure and function. Finally, the clinical outcomes, including heart failure, other cardiovascular complications, or cardiovascular death, were not available in the present study. There are available data elucidating the prognostic value of right ventricular strain [38, 39].

Conclusions

RVGLS and RVGCS decreased in patients with DM and preserved LVEF. Abnormal diabetic metabolism could mediate reduced RVGLS mainly by impairing LVGLS in patients with preserved LVEF. Despite the partly mediating effect of LVGLS and LVGCS, the difference in RVGCS might be directly affected by the DM.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- CMR-FT:

-

Feature tracking

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- LVEDVI:

-

Left ventricular end-diastolic volume index

- LVESVI:

-

Left ventricular end-systolic volume index

- LVMI:

-

Left ventricular myocardial mass index

- LVRI:

-

Left ventricular remodeling index

- RVEF:

-

Right ventricular ejection fraction

- RVEDVI:

-

Right ventricular end-diastolic volume index

- RVESVI:

-

Right ventricular end-systolic volume index

- RVMI:

-

Right ventricular myocardial mass index

- RVRI:

-

Right ventricular remodeling index

References

Disease C, Management R. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(Suppl 1):S144-s174.

Pop-Busui R, Januzzi JL, Bruemmer D, Butalia S, Green JB, Horton WB, Knight C, Levi M, Rasouli N, Richardson CR. Heart failure: an underappreciated complication of diabetes a consensus report of the American diabetes association. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(7):1670–90.

Prázný M, Suplotova L, Gumprecht J, Kamenov Z, Fülöp T, Medvedchikov A, Rosenzweig D, Aleksandric M. Real-world characteristics, modern antidiabetic treatment patterns, and comorbidities of patients with type 2 diabetes in central and Eastern Europe: retrospective cross-sectional and longitudinal evaluations in the CORDIALLY® study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21(1):203.

Rubler S, Dlugash J, Yuceoglu YZ, Kumral T, Branwood AW, Grishman A. New type of cardiomyopathy associated with diabetic glomerulosclerosis. Am J Cardiol. 1972;30(6):595–602.

Lee MMY, McMurray JJV, Lorenzo-Almorós A, Kristensen SL, Sattar N, Jhund PS, Petrie MC. Diabetic cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2019;105(4):337–45.

Riehle C, Bauersachs J. Of mice and men: models and mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Basic Res Cardiol. 2018;114(1):2.

Dillmann WH. Diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2019;124(8):1160–2.

Davies MJ, Drexel H, Jornayvaz FR, Pataky Z, Seferović PM, Wanner C. Cardiovascular outcomes trials: a paradigm shift in the current management of type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21(1):144.

Kenny HC, Abel ED. Heart failure in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circ Res. 2019;124(1):121–41.

Whitaker ME, Nair V, Sinari S, Dherange PA, Natarajan B, Trutter L, Brittain EL, Hemnes AR, Austin ED, Patel K, et al. Diabetes mellitus associates with increased right ventricular afterload and Remodeling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Med. 2018;131(6):702.e707-702.e713.

Daniels LJ, Wallace RS, Nicholson OM, Wilson GA, McDonald FJ, Jones PP, Baldi JC, Lamberts RR, Erickson JR. Inhibition of calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II restores contraction and relaxation in isolated cardiac muscle from type 2 diabetic rats. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):89.

Santamore WP, Dell’Italia LJ. Ventricular interdependence: significant left ventricular contributions to right ventricular systolic function. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1998;40(4):289–308.

Dini FL, Pugliese NR, Ameri P, Attanasio U, Badagliacca R, Correale M, Mercurio V, Tocchetti CG, Agostoni P, Palazzuoli A. Right ventricular failure in left heart disease: from pathophysiology to clinical manifestations and prognosis. Heart Fail Rev. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-022-10282-2.

Triposkiadis F, Xanthopoulos A, Boudoulas KD, Giamouzis G, Boudoulas H, Skoularigis J. The interventricular septum: structure, function, dysfunction, and diseases. J Clin Med. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11113227.

Sanz J, Sánchez-Quintana D, Bossone E, Bogaard HJ, Naeije R. Anatomy, function, and dysfunction of the right ventricle: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(12):1463–82.

Ojha V, Khalique OK, Khurana R, Lorenzatti D, Leung SW, Lawton B, Slesnick TC, Cavalcante JC, Ducci CB, Patel AR, et al. Highlights of the virtual society for cardiovascular magnetic resonance 2022 scientific conference: CMR: improving cardiovascular care around the world. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2022;24(1):38.

Xu J, Yang W, Zhao S, Lu M. State-of-the-art myocardial strain by CMR feature tracking: clinical applications and future perspectives. Eur Radiol. 2022;32(8):5424–35.

Guo R, Weingärtner S, Šiurytė P, Stoeck C, Füetterer M, Adrienne C-W, Suinesiaputra A, Jerosch-Herold M, Nezafat R. Emerging techniques in cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J Magn Reson Imag. 2022;55(4):1043–59.

Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes. standards of medical care in diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(Suppl 1):S15-s33.

Bollen KA, Stinet Robert. Direct and indirect effects: classical and bootstrap estimates of variability. Sociol Methodol. 1990;20:115.

Ferreira-Divino LF, Suvitaival T, Rotbain Curovic V, Tofte N, Trošt K, Mattila IM, Theilade S, Winther SA, Hansen TW, Frimodt-Møller M, et al. Circulating metabolites and molecular lipid species are associated with future cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in type 1 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21(1):135.

Lundgren JR, Færch K, Witte DR, Jonsson AE, Pedersen O, Hansen T, Lauritzen T, Holst JJ, Vistisen D, Jørgensen ME, et al. Greater glucagon-like peptide-1 responses to oral glucose are associated with lower central and peripheral blood pressures. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):130.

Akawi N, Checa A, Antonopoulos AS, Akoumianakis I, Daskalaki E, Kotanidis CP, Kondo H, Lee K, Yesilyurt D, Badi I, et al. Fat-secreted Ceramides regulate vascular redox state and influence outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(20):2494–513.

Pofi R, Giannetta E, Galea N, Francone M, Campolo F, Barbagallo F, Gianfrilli D, Venneri MA, Filardi T, Cristini C, et al. Diabetic Cardiomiopathy progression is triggered by miR122-5p and involves extracellular matrix: A 5-year prospective study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14(6):1130–42.

Salvador DB Jr, Gamba MR, Gonzalez-Jaramillo N, Gonzalez-Jaramillo V, Raguindin PFN, Minder B, Gräni C, Wilhelm M, Stettler C, Doria A, et al. Diabetes and myocardial fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15(5):796–808.

Zhang H, Shi C, Yang L, Zhang N, Li G, Zhou Z, Gao Y, Liu D, Xu L, Fan Z. Quantification of early diffuse myocardial fibrosis through 7.0 T cardiac magnetic resonance T1 mapping in a type 1 diabetic mellitus mouse model. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.28207.

Liu X, Gao Y, Guo YK, Xia CC, Shi R, Jiang L, Shen MT, Xie LJ, Peng WL, Qian WL, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance T1 mapping for evaluating myocardial fibrosis in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: correlation with left ventricular longitudinal diastolic dysfunction. Eur Radiol. 2022;32(11):7647–56.

Hamabe L, Mandour AS, Shimada K, Uemura A, Yilmaz Z, Nagaoka K, Tanaka R. Role of two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography in early detection of left ventricular dysfunction in dogs. Animals Open Access J MDPI. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082361.

Brand A, Bathe M, Oertelt-Prigione S, Seeland U, Rücke M, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Stangl K, Knebel F, Stangl V, Dreger H. Right heart function in impaired left ventricular diastolic function: 2D speckle tracking echocardiography-based and Doppler tissue imaging-based analysis of right atrial and ventricular function. Echocardiography. 2018;35(1):47–55.

Shao G, Cao Y, Cui Y, Han X, Liu J, Li Y, Li N, Liu T, Yu J, Shi H. Early detection of left atrial and bi-ventricular myocardial strain abnormalities by MRI feature tracking in normotensive or hypertensive T2DM patients with preserved LV function. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2020;20(1):196.

Kroeker CA, Shrive NG, Belenkie I, Tyberg JV. Pericardium modulates left and right ventricular stroke volumes to compensate for sudden changes in atrial volume. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284(6):H2247-2254.

Naeije R, Badagliacca R. The overloaded right heart and ventricular interdependence. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113(12):1474–85.

Todo S, Tanaka H, Yamauchi Y, Yokota S, Mochizuki Y, Shiraki H, Yamashita K, Shono A, Suzuki M, Sumimoto K, et al. Association of left ventricular longitudinal myocardial function with subclinical right ventricular dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20(1):212.

Paneni F, Gregori M, Tocci G, Palano F, Ciavarella GM, Pignatelli G, Marra A, Sciarretta S, Ferrucci A, Volpe M. Do diabetes, metabolic syndrome or their association equally affect biventricular function? Tissue Doppler Study Hypertens Res. 2013;36(1):36–42.

Gorter TM, Streng KW, van Melle JP, Rienstra M, Dickinson MG, Lam CSP, Hummel YM, Voors AA, Hoendermis ES, van Veldhuisen DJ. Diabetes mellitus and right ventricular dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2018;121(5):621–7.

Huang J, Li L, Fan L, Chen DL. Evaluation of right ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunctions in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with poor Glycemic control by layer specific global longitudinal strain and strain rate. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2022;14(1):49.

Linssen PBC, Veugen MGJ, Henry RMA, van der Kallen CJH, Kroon AA, Schram MT, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Stehouwer CDA. Associations of (pre)diabetes with right ventricular and atrial structure and function: the Maastricht Study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19(1):88.

Hamada-Harimura Y, Seo Y, Ishizu T, Nishi I, Machino-Ohtsuka T, Yamamoto M, Sugano A, Sato K, Sai S, Obara K, et al. Incremental Prognostic Value of Right Ventricular Strain in Patients With Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(10):e007249.

Bianco CM, Farjo PD, Ghaffar YA, Sengupta PP. Myocardial mechanics in patients with normal LVEF and diastolic dysfunction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(1 Pt 2):258–71.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81771887, 82120108015), and the 1·3·5 project for disciplines of excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (ZYGD18013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LY designed the study and is the guarantor of this research. YZG and GYK provide fund support. SR and QWL conducted the data collection and statistical analysis. LXM, GY, JL, and XHY participated in the data collection. SR drafted the manuscript. LY, YZG, and GYK critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet the authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The institutional review board approved this study, and informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this investigation.

Consent for publication

The manuscript was approved by all authors for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, R., Yang, ZG., Guo, YK. et al. The right ventricular dysfunction and ventricular interdependence in patients with DM: assessment using cardiac MR feature tracking. Cardiovasc Diabetol 22, 93 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-01806-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-01806-7