Abstract

Background

Coronaviruses are notorious pathogens that cause diarrheic and respiratory diseases in humans and animals. Although the epidemiology and pathogenicity of coronaviruses have gained substantial attention, little is known about bovine coronavirus in cattle, which possesses a close relationship with human coronavirus. Bovine torovirus (BToV) is a newly identified relevant pathogen associated with cattle diarrhoea and respiratory diseases, and its epidemiology in the Chinese cattle industry remains unknown.

Results

In this study, a total of 461 diarrhoeic faecal samples were collected from 38 different farms in three intensive cattle farming regions and analysed. Our results demonstrated that BToV is present in China, with a low prevalence rate of 1.74% (8/461). The full-length spike genes were further cloned from eight clinical samples (five farms in Henan Province). Phylogenetic analysis showed that two different subclades of BToV strains are circulating in China. Meanwhile, the three BToV strains identified from dairy calves, 18,307, 2YY and 5YY, all contained the amino acid variants R614Q, I801T, N841S and Q885E.

Conclusions

This is the first report to confirm the presence of BToV in beef and dairy calves in China with diarrhea, which extend our understanding of the epidemiology of BToVs worldwide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Calf scours, also known as calf diarrhoea, is an enteric disease complex in young calves and is regarded as the leading cause of mortality in dairy calves, causing severe economic losses to the cattle industry worldwide. The causes of calf scours are varied and complex, including infectious and non-infectious factors. In recent decades, a large number of infectious agents have been identified to be associated with calf scours, including bacteria, viruses and parasites. Thus far, the viral pathogens that cause calf diarrhoea include bovine coronavirus (BCoV) [1], bovine rotavirus (BRV) [2], bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV) [3], bovine torovirus (BToV) [4], bovine kobuvirus (BKoV) [5], bovine astrovirus (BAstV) [6], bovine norovirus (BNoV) [7], bovine enterovirus (BEV) and bovine nebovirus (BNeV) [8].

Torovirus (ToV) is a newly identified enveloped, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus that belongs to the subfamily Toroviridaein the family Coronaviridae, order Nidovirales [9]. The genome of ToV is 25–30 kb in length and contains two large open reading frames (ORFs) that encode two nonstructural proteins, ORF1a and ORF1ab, and four structural proteins, the spike (S), membrane (M), haemagglutinin-esterase (HE), and nucleocapsid (N) proteins [10].

Coronaviruses have drawn significant attention as a result of their pathogenicity toward humans and animals, as they usually cause significant respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), porcine epidemic diarrhoea (PED), and transmissible gastroenteritis (TGE). Similar to other members of Coronaviridae, ToV can infect a wide range of animals, including humans. In recent decades, ToV has been identified in humans, horses, cattle, and pigs worldwide, and the clinical sign of ToV infection is gastroenteritis; however, its role remains unclear. BToV was first identified in America from diarrhoeic calves in 1979 [11]. Since then, BToV has been reported in France, South Africa, Costa Rica, Canada, Venezuela, Hungary, Austria, Japan, South Korea, Brazil and, in recent years, Turkey and Croatia, which suggests that it has become a worldwide problem [4, 12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. It is associated with respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases. An artificial inoculation trial also revealed the pathogenesis of BToV in cattle [11, 28]. Although these data strongly suggest that BToV is relevant to diarrhoea in cattle, to our knowledge, there have been no reports of BToV in China to date. Herein, our study investigated the presence and molecular characteristics of BToV in faecal samples from diarrhoeic calves in China. This report is the first to describe the presence of BToV in Chinese beef and dairy, and to analyse the genetic characteristics and phylogenetic relationships between the Chinese BToV, BToV reference strains and other representative toroviruses.

Results

BToV detection and coinfections

A total of 461 faecal samples from calves with clinical signs of diarrhoea were detected by RT-PCR, and the results demonstrated that 1.74% (8/461) of the diarrhoeal samples were positive for BToV. Moreover, 5 out of the 38 farms were positive for BToV. Notably, BToV was found in diarrhoeal faecal samples from only Henan Province, and the overall detection rate was 3.62% (8/221) [4.07% (5/123) and 3.06% (2/98) in dairy calves and beef cavles, respectively] (Table 1, Fig. 1). The positive rate of farms was 35.7% (5/14). Detailed test results of the eight positive samples are shown in Table 2.

Number of calves and farms from three provinces in China, 2017–2019. The n values indicate the total number of samples in each province, the x values indicate the total number of farms in each province, and the positive rate indicates the BToVs positive rate. The map was created by MAPGIS (version 6.7)

PCR amplification of the S genes

The full-length S genes were successfully cloned from 8 positive samples from 5 different farms in Henan Province. The newly determined sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MT364036 to MT364043 (Table 2).

Molecular characterization of the S genes

The 8 S genes were 4755 bp in length, and each encoded a protein of 1585 amino acid (aa). Sequence comparisons showed that all 8 S genes shared 95.4–99.9% nt identity and 95.6–99.8% aa identity with each other. They also shared 94.3–97.7% nt identity and 95.1–98.4% aa identity with all 11 full-length BToV S genes available in GenBank and shared 92.0–92.9% nt identity and 93.6–95.3% aa identity with goat torovirus S genes (KR527150); however, they shared 73.7–75.9% nt identity and 75.8–79.6% aa identity with the human, equine and swine torovirus S genes (JQ860350, MG996765 and KM403390).

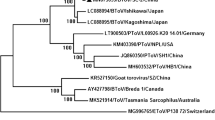

Phylogenetic analyses were further performed for the newly identified Chinese BToV strains. The results showed that the 8 newly identified Chinese BToV strains were clustered in the same group with other BToVs and were distantly related to the ToV strains derived from human, equine and porcine sources. A phylogenetic tree based on the aa sequences of the complete S gene sequences using the neighbour-joining method demonstrated that the 8 S genes identified in this study were clustered into two different subclades of BToV strains, which clustered closely with the Turkish strain (MG957146) and the Japanese strain (AB526863) (Fig. 2).

Recombination events among the S genes of the BToV strains were further investigated using RDP4 software, but no correlations were detected. This result indicated that no recombination had occurred between the BToVs (data not shown). However, the available BToV S gene sequences are limited; therefore, there may not be enough data available to confirm this result. Therefore, further studies of BToVs are required.

Compared with the other BToV S gene sequences, 3/8 sequences identified in this study, all of which were obtained from dairy strains, had four identical aa variants (R614Q, I801T, N841S and Q885E). In addition, no frame shifts, deletions, insertions or recombination events were observed in the S gene sequences from any strain identified in the present study.

Discussion

Similar to other countries and regions in the world, diarrhoea is one of the most common disease symptoms in calves in China, leading to great economic losses. The financial losses arise not only from mortality but also from the cost of medication (especially antimicrobials), the labour needed to treat sick calves, the reduced growth of calves, and the increased age and difficulty at first calving. Calf diarrhoea has a multifactorial aetiology in which viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and environmental factors (feeding, housing, and hygienic conditions) play a role. Recently, several viral pathogens were identified to be associated with calf diarrhoea, such as BToV, BNoV, BNebV, BAstV, BVDV, BKV, BRV and BCoV. Unusually noticeably, BToV and BCoV are two distinct viruses and they have different sequences. And the preliminary identification was based on the primers designed according to their respective conservative regions, without mutual interference. In addition, the detection rate of BCoV is much higher than that of BToV in all clinic cases (results not shown) in our study.

BToV is a viral pathogen of calves that causes diarrhoea and respiratory tract infections in calves and adult cattle and is globally responsible for serious economic losses in cattle production. However, BToV is usually not included in algorithms used to diagnose calf diarrhoea. To date, BToV has been described in diarrhoeic calves in various countries [4, 12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. According to a previous study [29], BToV alone has been shown to act as an enteric pathogen in cattle, and has also been regarded as a common relevant pathogen of cattle in the European and American cattle industries. Also, BToV can be identified in feces from clinically healthy caves, although there was a significant greater number positive samples in the diarrheic calves than in the healthy calves (P < 0.01) [20], which makes assessing the clinical relevance of BToV very difficult and the role of BToV in calf diarrhea still remains undetermined. However, we believe that our study will, to some extent, help to clarify the role of BToV in diarrhoea in calves. BRV, BCoV and BVDV are considered the major diarrhoea-inducing pathogens in China [30]. Notably, three out of eight BToV positive samples detected only BToV in our study, the other five samples were tested and positive for some other diarrhea pathogens. The results of pathogenic detection may indicated that BToV is a relevant pathogen in cattle, and it may also play a synergistic role in coinfections [23]. However, to date, little attention has been given to BToVs as causes of calf diarrhoea in China.

The percentage of BToV infection found in this study (1.74%) is comparatively lower than that reported in other studies: 2.9% in South Korea [22], 4.7% in Turkey [24], 5.2% in Austria [19], 6.25% in Brazil [23], 8.4% in Japan [21], 9.7% in the USA [18], 36.4% in Canada [4], and 43.2% in Croatia [26]. Despite these differences, one cannot make a reliable comparison among these percentages because of the limited sample size used in the present and previous studies. Interestingly, the eight positive samples were all obtained from Henan Province. No positive samples were obtained from Sichuan and Jiangsu Provinces, and no positive samples were detected among the yak samples. This may be due to geographic location, breed and feeding mode. These results showed that BToV is present in cattle in China. Our findings have significant implications for the diagnosis and control of calf diarrhoea in China and reveal the necessity for the development of prevention and control strategies, including the study of vaccine potency and the development of therapies. Previously, BToV-associated diarrhoea has not been reported in China, and no information about BToV epidemiology was available. Therefore, the epidemiology of BToV in China needs to be further evaluated.

The S protein is responsible for the antigenic properties of the virus and contains the binding site for the cell-surface receptor. Compared with the S genes of BToV strains identified from other countries, the Chinese BToV S genes shared a high nt/aa identity sequence homology with the S genes of Japanese BToV (94.3–97.1%/95.1–97.9%), Turkey BToV (95.9–97.7%/96.1–98.4%), Dutch BToV (95.5–97.3%/96.2–98.2%) and American BToV (Breda 1 strain, the first BToV detected in the USA in 1982) (95.2–96.2%/96.3–97.2%). The S genes of the newly identified Chinese strains are more closely related to those of the Turkish BToVs than those of the Japanese BToVs. Moreover, the Chinese BToVs shared low nucleotide identity with non-bovine ToV strains, such as human, equine, and porcine strains. Phylogenetic analysis based on the complete S gene sequences showed that the eight newly identified Chinese BToV strains were clustered into two different subclades, as described above. Comparison of the nt and deduced aa sequences of the complete S genes of the Chinese BToV strains showed that they were highly conserved in this region. Although the molecular characterization revealed some nt and aa differences between the strains identified in this study and the reference strains, the Chinese sequences were generally clustered with the reference strains. In this study, S protein was chosen for analysis because it may play an important role in pathogenesis. In fact, there are very few reports on these, therefore no more analysis has been done in this article. However, we believe that with the gradual deepening of research on BToV, these will become clearer.

Coronaviruses have been studied in detail, but little is known about ToVs. One important reason for this gap in knowledge is that ToVs have not been propagated in cell culture, with the sole exception of the Berne virus. However, research on this virus has been limited partly because of insufficient information and the lack of an available in vitro system for conducting further studies. Limited genomic information has also restricted our understanding of the virus. This has hampered the detailed characterization of the molecular biology, evolution, and taxonomy of this virus. Therefore, additional sequence information is expected to facilitate further research on virus antigenicity, virulence, infection, and replication in animals. This study will improve the understanding of the epidemiology, evolutionary pattern and genetic diversity of BToVs.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study first demonstrated the presence of BToV in Chinese beef and dairy and suggested that two different subclades of BToV strains are circulating in China, which might pose a potential threat to the cattle industry in China. This study highlights the importance of continuous surveillance and the evaluation of the epidemiology and pathology of BToV in domestic cattle. These findings have implications for the diagnosis and control strategies used for this newly identified virus. Additionally, our findings will enhance the current understanding of the genetic evolution of BToV.

Methods

Faecal samples

A total of 461 faecal samples were collected from calves with diarrhoea from 38 farms in three intensive cattle farming regions of China from September 2017 to July 2019. These farms were in Henan (14 farms, n = 221), Jiangsu (three farms, n = 42) and Sichuan (21 farms, n = 198). These three provinces are the main cattle production areas in central, eastern and western China, and the geographical distance between the two most distant farms was > 2000 km. At each cattle farm, the samples were randomly collected from calves with signs of clinical diarrhoea, and were directly collected with sampling bags during defecation by ourselves or farm veterinarian, the sampling requirements are the same. The ages of the tested calves ranged from 2 days to 4 months. All samples were transported on ice and stored at − 80 °C.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

The faecal samples were fully resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (1:10 w/v) and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, followed by filtration through a 0.22 μm filter. Total RNA was extracted from 200 μL of the faecal suspension using the TaKaRa MiniBEST Viral RNA/DNA Extraction Kit Ver. 5.0 (TaKaRa Bio Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the cells were maintained at − 80 °C. cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Transcription Kit (TaKaRa Bio Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and stored at − 20 °C.

Detection of BToVs

BToVs were detected by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) targeting a 603 bp fragment of the M gene, as previously reported [31]. PCR amplification was conducted in a 20 μL reaction volume containing 1.0 μL forward primer (10.0 μM), 1.0 μL reverse primer (10.0 μM), 2.0 μL cDNA, 10.0 μL Premix Taq (TaKaRa Taq Version 2.0) (TaKaRa Bio Inc.) and an appropriate volume of double-distilled water. The PCR conditions were as follows: 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 49 °C for 40 s and 72 °C for 50 s, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. For each reaction, sterile ddH2O was used as a negative control. All of the RT-PCR products were verified by sequencing at Sangon Biotech (Zhengzhou, China).

To investigate coinfection with other pathogens, the eight BToV-positive samples were subjected to previously described specific RT-PCR assays for BNoV, BCoV, BRV (A, B, C), BVDV, BKV, BAstV and BNebV (The information of primers see Table S1). The faecal samples were also tested for Coccidium species and Cryptosporidium species using the sucrose floatation method. At the time of sampling, all the 8 BToV-positive cattle had been treated with antibiotics (including sulfonamides, penicillin, cephalosporin, and enrofloxacin, which were less efficient), so no bacterial isolation and identification was carried out.

Amplification and sequencing of the S gene

Four pairs of overlapping primers were designed (reference sequence accession number: MG957146) to amplify the complete S gene according to the BToV sequences available in GenBank (Table 3). All amplification products were purified using the Omega Gel kit (Omega) by following the manufacturer’s instructions, after which the products were ligated into the pMD18-T simple vector (TaKaRa Bio, Inc.) and transformed into DH5α competent Escherichia coli cells (TaKaRa Bio Inc.). For each product, three to five colonies were selected and sequenced (Sangon, China) in both directions. The sequences were assembled using SeqMan software (version 7.0; DNASTAR Inc., WI, USA).

Homology, phylogenetic, and recombination analyses

Sixteen reference sequences of the complete S gene from different ToV strains were downloaded from GenBank for use in the downstream analyses. The homologies of the nt and deduced aa sequences were determined using the MegAlign module in DNASTAR 7.0 software (DNASTAR Inc.). Multiple sequence alignment was performed, and subsequently, a neighbour-joining tree was constructed with 1000 bootstrap replicates in MEGA 7.0. Recombination events were assessed using SimPlot software (version 3.5.1) and RDP 4 software with the RDP, GeneConv, Chimaera, MaxChi, BootScan, SiScan, and 3Seq methods [32].

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the GenBank repository (MT364036 to MT364043). The data are simultaneously made available to ENA in Europe and the DNA Data Bank of Japan.

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files, and the dataset analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BAstV:

-

bovine astrovirus

- BCoV:

-

bovine coronavirus

- BKoV:

-

bovine kobuvirus

- BNoV:

-

bovine norovirus

- BRoV:

-

bovine rotavirus

- BToV:

-

bovine torovirus

- BVDV:

-

bovine viral diarrhea virus

- ToV:

-

torovirus

References

Cho KO, Hasoksuz M, Nielsen PR, Chang KO, Lathrop S, Saif LJ. Cross-protection studies between respiratory and calf diarrhea and winter dysentery coronavirus strains in calves and RT-PCR and nested PCR for their detection. Arch Virol. 2001;146(12):2401–19.

Sharp CP, Gregory WF, Mason C, Bronsvoort BM, Beard PM. High prevalence and diversity of bovine astroviruses in the faeces of healthy and diarrhoeic calves in south West Scotland. Vet Microbiol. 2015;178(1–2):70–6.

Oem JK, An DJ. Phylogenetic analysis of bovine astrovirus in Korean cattle. Virus Genes. 2014;48(2):372.

Duckmanton L, Carman S, Nagy E, Petric M. Detection of bovine torovirus in fecal specimens of calves with diarrhea from Ontario farms. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36(5):1266–70.

Reuter G, Egyed L. Bovine kobuvirus in europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(5):822–3.

Tse H, Chan WM, Tsoi HW, Fan RY, Lau CC, Lau SK, Woo PC, Yuen KY. Rediscovery and genomic characterization of bovine astroviruses. J Gen Virol. 2011;92(8):1888–98.

Shi Z, Wang W, Xu Z, Zhang X, Lan Y. Genetic and phylogenetic analyses of the first GIII.2 bovine norovirus in China. BMC Vet Res. 2019;15(1):311.

Pourasgari F, Kaplon J, Sanchooli A, Fremy C, Karimi-Naghlani S, Otarod V, Ambert-Balay K, Mojgani N, Pothier P. Molecular prevalence of bovine noroviruses and neboviruses in newborn calves in Iran. Arch Virol. 2018;163(5):1271–7.

Snijder EJ, Ederveen J, Spaan WJ, Weiss M, Horzinek MC. Characterization of Berne virus genomic and messenger RNAs. J Gen Virol. 1988;69(Pt 9):2135–44.

Draker R, Roper RL, Petric M, Tellier R. The complete sequence of the bovine torovirus genome. Virus Res. 2006;115(1):56–68.

Woode GN, Reed DE, Runnels PL, Herrig MA, Hill HT. Studies with an unclassified virus isolated from diarrheic calves. Vet Microbiol. 1982;7(3):221–40.

Koopmans M, van Wuijckhuise-Sjouke L, Schukken YH, Cremers H, Horzinek MC. Association of diarrhea in cattle with torovirus infections on farms. Am J Vet Res. 1991;52(11):1769–73.

Vorster JH, Gerdes GH. Breda virus-like particles in calves in South Africa. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1993;64(2):58.

Perez E, Kummeling A, Janssen MM, Jimenez C, Alvarado R, Caballero M, Donado P, Dwinger RH. Infectious agents associated with diarrhoea of calves in the canton of Tilaran, Costa Rica. Prev Vet Med. 1998;33(1–4):195–205.

Hoet AE, Cho KO, Chang KO, Loerch SC, Wittum TE, Saif LJ. Enteric and nasal shedding of bovine torovirus (Breda virus) in feedlot cattle. Am J Vet Res. 2002;63(3):342–8.

Matiz K, Kecskemeti S, Kiss I, Adam Z, Tanyi J, Nagy B. Torovirus detection in faecal specimens of calves and pigs in Hungary: short communication. Acta Vet Hung. 2002;50(3):293–6.

Hoet AE, Chang KO, Saif LJ. Comparison of ELISA and RT-PCR versus immune electron microscopy for detection of bovine torovirus (Breda virus) in calf fecal specimens. J Vet Diagn Investig. 2003;15(2):100–6.

Hoet AE, Nielsen PR, Hasoksuz M, Thomas C, Wittum TE, Saif LJ. Detection of bovine torovirus and other enteric pathogens in feces from diarrhea cases in cattle. J Vet Diagn Investig. 2003;15(3):205–12.

Haschek B, Klein D, Benetka V, Herrera C, Sommerfeld-Stur I, Vilcek S, Moestl K, Baumgartner W. Detection of bovine torovirus in neonatal calf diarrhoea in Lower Austria and Styria (Austria). J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health. 2006;53(4):160–5.

Kirisawa R, Takeyama A, Koiwa M, Iwai H. Detection of bovine torovirus in fecal specimens of calves with diarrhea in Japan. J Vet Med Sci. 2007;69(5):471–6.

Ito T, Okada N, Fukuyama S. Epidemiological analysis of bovine torovirus in Japan. Virus Res. 2007;126(1–2):32–7.

Park SJ, Oh EH, Park SI, Kim HH, Jeong YJ, Lim GK, Hyun BH, Cho KO. Molecular epidemiology of bovine toroviruses circulating in South Korea. Vet Microbiol. 2008;126(4):364–71.

Nogueira JS, Asano KM, de Souza SP, Brandao PE, Richtzenhain LJ. First detection and molecular diversity of Brazilian bovine torovirus (BToV) strains from young and adult cattle. Res Vet Sci. 2013;95(2):799–801.

Gulacti I, Isidan H, Sozdutmaz I. Detection of bovine torovirus in fecal specimens from calves with diarrhea in Turkey. Arch Virol. 2014;159(7):1623–7.

Lamouliatte F, du Pasquier P, Rossi F, Laporte J, Loze JP. Studies on bovine Breda virus. Vet Microbiol. 1987;15(4):261–78.

Lojkic I, Kresic N, Simic I, Bedekovic T. Detection and molecular characterisation of bovine corona and toroviruses from Croatian cattle. BMC Vet Res. 2015;11:202.

Ito T, Okada N, Okawa M, Fukuyama S, Shimizu M. Detection and characterization of bovine torovirus from the respiratory tract in Japanese cattle. Vet Microbiol. 2009;136(3–4):366–71.

Pohlenz JF, Cheville NF, Woode GN, Mokresh AHJVP. Cellular lesions in intestinal mucosa of gnotobiotic calves experimentally infected with a new unclassified bovine virus (Breda virus). Vet Pathol. 1984;21(4):407–17.

Aita T, Kuwabara M, Murayama K, Sasagawa Y, Yabe S, Higuchi R, Tamura T, Miyazaki A, Tsunemitsu H. Characterization of epidemic diarrhea outbreaks associated with bovine torovirus in adult cows. Arch Virol. 2012;157(3):423–31.

Deng M, Ji S, Fei W, Raza S, He C, Chen Y, Chen H, Guo A. Prevalence study and genetic typing of bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) in four bovine species in China. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0121718.

Park SI, Jeong C, Kim HH, Park SH, Park SJ, Hyun BH, Yang DK, Kim SK, Kang MI, Cho KO. Molecular epidemiology of bovine noroviruses in South Korea. Vet Microbiol. 2007;124(1–2):125–33.

Martin DP, Murrell B, Golden M, Khoosal A, Muhire B. RDP4: Detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol. 2015;1(1):vev003.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the cattle farms for submitting the samples to our laboratory. And thank engineer Shuhong Wang for providing us with maps and markers.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Beef Cattle Industrial Technology System (CARS-37), the Key Program for Science and Technology Development of Henan (192102110074), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFD0501700), as well as the Independent Innovation Fund Project in Henan Academy of Agricultural Science (2018ZC56).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZHS, WJW, CXC, ZXX collected the samples, conceived and designed the experiments. ZHS, WJW, JW and YLL performed the experiments. ZHS, XZZ and WJW analyzed the data and wrote the paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Henan Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Approval number SYXK 2014–0007). Experimental protocols for obtaining bovine clinical samples used in this study were carried out in strict accordance with the Animal Ethics Procedures and Guidelines of China. The sample collection work was approved with signed informed consent from the cattle farm owner.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 : Table S1.

Primers used for the detection of viruses in fecal samples from diarrheic calves.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, Z., Wang, W., Chen, C. et al. First report and genetic characterization of bovine torovirus in diarrhoeic calves in China. BMC Vet Res 16, 272 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-020-02494-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-020-02494-1