Abstract

Background

In response to students´ poor ratings of emergency remote lectures in internal medicine, a team of undergraduate medical students initiated a series of voluntary peer-moderated clinical case discussions. This study aims to describe the student-led effort to develop peer-moderated clinical case discussions focused on training cognitive clinical skill for first and second-year clinical students.

Methods

Following the Kern Cycle a didactic concept is conceived by matching cognitive learning theory to the competence levels of the German Medical Training Framework. A 50-item survey is developed based on previous evaluation tools and administered after each tutorial. Educational environment, cognitive congruence, and learning outcomes are assessed using pre-post-self-reports in a single-institution study.

Results

Over the course of two semesters 19 tutors conducted 48 tutorials. There were 794 attendances in total (273 in the first semester and 521 in the second). The response rate was 32%. The didactic concept proved successful in attaining all learning objectives. Students rated the educational environment, cognitive congruence, and tutorials overall as “very good” and significantly better than the corresponding lecture. Students reported a 70%-increase in positive feelings about being tutored by peers after the session.

Conclusion

Peer-assisted learning can improve students´ subjective satisfaction levels and successfully foster clinical reasoning skills. This highlights successful student contributions to the development of curricula.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The SARS-CoV2-pandemic´s strain on medical schools has been hard [1,2,3] since many stakeholders in medical education are both caregivers and instructors. With limited staff available for teaching [4] and reduced on-campus presence, many classes were moved to emergency remote teaching courses [5, 6]. Emergency remote teaching is the “alternate delivery mode due to crisis circumstances” as opposed to well-planned online teaching [7].

At Technical University of Munich (TUM) most lectures, seminars, and bedside teachings werecanceled or moved to emergency remote teaching in the spring semester of 2020. Within the student council, the notion quickly gained traction that a peer-assisted learning (PAL) program ought to be established to alleviate pressure on faculty staff while providing students with a safe environment for the acquisition and training of their clinical reasoning skills.

Several universities have promoted PAL programs. It refers to the “development of knowledge and skill through explicit active helping and supporting among status equals” [8]. Benefits of PAL are i) a similar knowledge base and an understanding of obstacles while studying (cognitive congruence) [9, 10], ii) a positive learning environment void of complicated student-instructor relationships due to similar social status (social congruence) [9, 10] and iii) relieving pressure on faculty staff [11]. PAL has been employed in teaching anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry [12], as well as communication [13], physical examination [14], and other procedural skills [15, 16]. There students have been shown to assume the roles of lecturers [17], clinical or practical teachers [18], mentors [19], learning facilitators [20, 21], role models [21], and assessors [22]. In our study, we wish to introduce a curriculum that was fully designed, delivered, and evaluated by undergraduate students based on the Kern Cycle [23] with minimum intervention by faculty staff. We thus empower students to holistically assume all of the twelve roles of a teacher as proposed by Harden and Crosby in 2000 [24].

Targeted at students in the clinical phase of their studies, we developed the novel Integrated Clinical Case Discussions (ICCD) that emphasize the training of clinical reasoning skills that are at the heart of the recently released second edition of the competence-based German Medical Training Framework (GMTF) [25]. In accordance with the GMTF three central learning objectives were identified: i) transfer of clinical knowledge, ii) fostering of diagnostic management skills, and iii) enabling students to discuss findings and procedures in a team. Clinical Case Discussions (CCD) have been shown to enhance clinical and scientific reasoning skills [20, 26], self-directed learning [26], and exchange with colleagues [27].

This study seeks to explore whether a peer-moderated clinical case discussion can improve students´ subjective satisfaction level with learning opportunities in case of emergency remote teaching.

Setting and participants

For their studies of internal medicine students at TUM attend two series of lectures in two consecutive semesters: In the spring semester of their first clinical year, there is a series of lectures on the cardiovascular and hematologic systems. In the subsequent fall semester, they hear a series of lectures on nephrology, gastroenterology, and endocrinology. Students are routinely requested to evaluate all lectures on a five-point Likert scale. When in the spring semester of 2020 all lectures were moved to an emergency remote teaching format, the mean evaluation of lectures on internal medicine dropped by 1.44 points as opposed to the six years prior (from 1.96 to 3.4, where 1 denoted the greatest and 6 the lowest level of satisfaction).

To provide their peers with an additional opportunity to review the lectures´ content, three students initiated the peer-moderated Integrated Clinical Case Discussions. In the ICCDs we applied a lecture´s content to a patient´s case with special emphasis on diagnostic and management skills in accordance with GMTF level 2 (i.e. clinical reasoning skills).

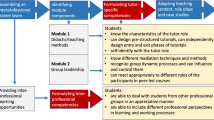

We prepared ICCDs for 12 topics in the fall semester of 2020 and 12 topics in the spring semester of 2021. For each topic we allocated two 90-min sessions in the week immediately following the general lecture on the topic. We were able to offer one face-to-face and one online tutorial for 11 topics. Due to hygiene regulations, the remaining 13 topics were discussed exclusively online twice a week. The time resources needed for one tutorial included i) 18 h for the tutor to prepare and hold the ICCD, ii) 3.5 h for the organizing students to recruit and mentor tutors as well as to evaluate and advertise the sessions and iii) 1.5 h of supervision by the physician (Fig. 1). The remuneration was 250€ per tutor and tutorial and 246.66€ for each organizing student per month (In the first year: authors JR and NS—15 months, TW—5 months. This was later reduced to one organizing student only.). Tutors were trained and supervised by specialist physicians as part of their regular teaching duties (1.5 h per session). Physicians were not reimbursed by the ICCD team. ICCDs were completely voluntary. We advertised ICCDs through weekly email alerts and a note in students´ schedules.

Workflow for the preparation of one ICCD session. Three parties are involved in the preparation and implementation of an ICCD session: an administrative unit consisting of the organizing undergraduate students (*) and the TUM Medical Education Center (†) (bottom row), tutors (middle row) and clinical supervisors (top row). Their respective tasks are indicated at the relative time points for the preparation of one ICCD. The allotted time frame for each task per one ICCD session is included in round brackets. For their first meeting tutors and supervisors are provided with a checklist (‡), i.e. to i) define content-focal points, ii) select an appropriate clinical case iii) define a clinical skill essential for the successful completion of the case, and to iv) provide the tutor with important clinical findings (e.g. laboratory findings, images)

Methods

Conception of the didactic concept

ICCDs followed cognitive learning theory. Each session was set as an interactive problem-based learning scenario (Clinical Case Discussion), that facilitated learners´ active participation to organize and conceptualize information [28]. To prompt students to access pre-existing knowledge ICCD sessions started with a voluntary entry-exam of five multiple-choice questions. The prefix Integrated reflects the close alignment of student-led tutorials and the lectures conducted by faculty staff. ICCDs did not seek to introduce new facts but to offer a platform for reviewing and applying the lecture’s contents to a clinical case. Each ICCD comprised two clinical cases in which at least one skill apart from history taking was trained (usually the interpretation of laboratory findings). Tutors and lecturers chose a clinical case from the lecturer´s clinical experience that matched the lecture. Tutors then prepared a powerpoint presentation (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Washington, USA) to facilitate the case discussion, which was checked by the lecturer for medical content and by the organizing students for the didactic concept. Tutors delivered online sessions through a university zoom account (Zoom Video Communication Inc., 5.7.7, San Jose, California, USA) and—if under the Covid-regulations permissible—face-to-face in the lecturing hall. We instructed tutors to follow a modified version of Linsenmeyer´s approach [27] (Fig. 2). Briefly, tutees´ participation and teamwork were gradually increased by moving from anonymous multiple-choice questions to group discussions in breakout rooms and finally to discussing the ideal diagnostic procedures in the plenary session. An example of one case can be found in the supplementary material S1.

Typical outline of an ICCD session. We modified Linsenmeyer´s approach to stimulating interaction between students (Linsenmeyer, 2021). One ICCD session propagates along the x-axis from left to right. Several layers along the y-axis indicate the roles a tutor assumes at each time point, the teaching techniques they employ (examples provided below), and the level of interaction this is likely to be incentivize between tutees. A: Each session starts with a knowledge probe intended to activate students´ prior knowledge by asking five multiple-choice questions that participants must solve individually and anonymously. As indicated by the green triangle at the bottom of the figure this requires only a minimum level of interaction between students. B: Subsequently, tutors introduce the session´s clinical case and moderate a plenum discussion in which participants collectively take a patient´s history, determine an appropriate diagnostic algorithm, and list differential diagnoses. This gradually raises the level of interaction (upward slope of the triangle). C: In the next stage participants are assigned to break-out groups of two to four students in which they practice interpreting patient-specific clinical findings, lab results or different image modalities. Tutors switch from group to group to help if needed. D: Finally, the breakout groups meet back in the plenum and discuss their findings and differential diagnoses under the tutor´s moderation. We rated this as the most demanding level of interaction as it requires students to present in front of a larger group. At this point, tutors are oscillating between facilitating the discussion as different groups present their findings and providing direct instruction when explaining the meaning behind lab results/images, etc. Under the tutor’s guidance differential diagnoses are eliminated and the final diagnosis emerges. E: Lastly the tutor outlines treatment options. Due to time constraints, this was predominantly done in direct instruction

Recruitment and training of tutors

Tutors were recruited from the student body of those students who had completed the lecture on internal medicine and passed the exam. The recruitment process was based on Engel´s approach [17] and included a publicly shared application form and a job interview in which a shared decision was made on the topic best suited to the tutor´s interests and experience. A standardized curriculum was designed for tutors and delivered by a joint group of clinicians, the TUM Medical Education Center, and the organizing students who provided the impetus for ICCDs (Fig. 1). Mandatory training consisted of an introductory seminar on the ICCD´s didactic concept and a lecture on how to teach clinical reasoning skills and stimulate group interaction. Tutors then prepared their tutorial with their clinical supervisor as described above.

Questionnaire

Tutee evaluations were collected online at the end of each session using EvaSys V8.1 (evasys GmbH, Lueneburg, Germany). The survey comprised 50 self-report questions (supplementary material S2). Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). For selected items, we also asked open-ended questions.

The underlying concept of the evaluation tool was modeled on the Student´s Evaluations of Educational Quality Questionnaire (SEEQ), a validated and reproducible evaluation tool proposed by Marsh in 1982 [29]. Designed for summative assessment of faculty-administered teaching, the SEEQ had to be adapted to our specific needs. We adopted evaluation items “I Learning/Value”, “IV Group Interaction” and all applicable items of “III Organisation” and “V Individual Raport”, yet omitted items VI-IX, since participation was completely voluntary, and examinations were not part of the ICCDs. Following the SEEQ category “I Learning/Value” we compared students´ subjective assessments of gain in knowledge, skill, motivation, and overall grade [30] after attending only the general lecture with attending both lecture and ICCD. We excluded SEEQ-section “II Enthusiasm” since tutors would have to proactively volunteer to teach in addition to their regular workload. Instead, we wanted to measure tutors´ performance as levels of cognitive congruence and educational environment. The tutor intervention profile by De Grave [31]and the Student Course Experience Questionnaire by Paul Ginns [32] reflected the aforementioned categories in more detail than the SEEQ and served as a reference. (Appendix Table 1). We also asked tutees to identify roles the tutor had assumed for them as proposed by Bulte et al. [21]. Learning outcomes were assessed as comparative self-assessment (CSA) for aggregated data [33]. The questions´ wording was based on the GESIS survey guidelines [34].

We handed tutors a short survey that asked them to rate the helpfulness of the introductory seminar, their understanding of the overall concept, and their difficulties in preparing the ICCD and enjoyment of the process on a five-point Likert scale.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed data using SPSS Statistics for Windows version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Washington, USA). We included all surveys that had answers to more than 50% of all questions. If a student visited multiple sessions, only their first response to each question was included in the analysis. Learning outcomes and shifts in attitude toward peer teachers were computed as the CSA-gain as proposed by Raupach et al. (2011) [33]. Briefly, at the end of each session students were asked to retrospectively rate their expertise in the item before and after attending an ICCD session. The average net increase in self-assessment was then displayed as a percentage-wise increase over the average initial self-assessment. Qualitative, descriptive data were measured on a five-point Likert scale and analyzed using mean, mode, and standard deviation. Testing for statistical significance was performed using a two-tailed exact Chi-Square Test for categorical variables. Mann–Whitney-U-test was used for the comparison of metric variables with non-normal distribution between two groups (learning outcome). A p-value of 0.05 was chosen a priori. Effect size was calculated using Cramer´s V for descriptive data and correlations were computed using Spearman Correlation. Cronbach´s alpha was computed to test for internal consistency for the categories “cognitive congruence” and “educational environment”. Answers to open-ended questions were analyzed according to qualitative content analysis by Mayring [35]. Author JR developed the major categories deductively based on probable answers and supplemented them with subcategories inferred from students´ final responses. Another author, NS, checked categories for traceability. Finally, a category tree with specific anchor examples and defined subcategories emerged. The frequency of items and total number of student comments were recorded.

Results

Demography

In the fall semester of 2020, a total of 335 students enrolled in the general lecture, 149 (44.5%) of whom attended at least one ICCD session. In the subsequent spring semester, 334 students enrolled in the general lecture and 237 (71.0%) took part in at least one ICCD session. Some tutees attended multiple sessions throughout the semesters. In sum, we counted 273 student attendances in the first and 521 in the second semester, respectively.

We received evaluations from 32.4% of all participants (n = 125). 91 (72.8%) tutees were aged 25 or under and 96 tutees (76.8%) identified as female. This approximately reflected the general student population (female/male: 65/35; mean age: 24 years). Questionnaires without informed consent were excluded from further analysis.

We employed 19 tutors for the implementation of 48 ICCD sessions covering a total of 24 topics. Eleven (57.8%) of those tutors identified as female and 12 (63.1%) had gained previous experience in front-line tertiary teaching.

Acceptance of ICCD

The nature of the ICCD being an add-on to the standard curriculum, we aimed to create additional value to the core curriculum that could not be attained with lectures and seminars alone. Evaluation of the ICCD shall therefore be displayed in direct comparison to the corresponding lecture (Fig. 3). ICCDs were generally rated as excellent and significantly better than lectures for all categories: knowledge, skill, attitude, and overall grade. Effect size was greatest for overall grade (V = 0.58; p < 0.01) and smallest for gain in knowledge (V = 0.37; p < 0.01) in ICCDs as opposed to the lecture. We observed that gain in knowledge correlated with gain in skills (r = 0.56; p < 0.01) and overall evaluation of the ICCD session (r = 0.61; p < 0.01).

Evaluation of ICCD vs. lecture. A Kiviat diagram representing students´ mean subjective assessment after attending lectures alone (round dots) and after attending both lectures and ICCD (long dashes) in categories knowledge, skill, attitude, and overall grade each represented on one of the axes of the diagram. Students were asked to rate their gain in each of the categories for both tutorial and the respective lecture on a five-point Likert scale with 1 denoting the greatest and 5 the lowest degree of satisfaction. Questionnaires were administered immediately after each tutorial. Tutorials took place one week after the general lecture. All differences are significant (p < .01). Effect size was calculated using Cramer´s V

When asked how comfortable tutees felt about being tutored by peers for an ICCD, tutees indicated a 70% increase in positive feelings after the intervention (CSA gain = 69.57%, n = 111).

We received 57 answers to the open-ended questions on satisfaction and improvement suggestions (Table 1). In these answers, a total of 123 text segments (k) were identified and grouped into four categories. Most test segments praised the general format of the ICCD (k = 45). The second most frequent category included individual feedback on tutors (k = 40). The third category addressed learning value (k = 24) and the last category included improvement suggestions (k = 14).

Evaluation of Tutors

Mean cognitive congruence and educational environment for all sessions were rated as excellent at 1.26 (n = 121) and 1.35 (n = 107) respectively. Most tutees ascribed the roles “information provider” (n = 106, 84.4%) and “facilitator” (n = 87, 69.6%) to their tutors. Several tutees also rated their tutors as “role models” (n = 68,54.4%) and “assessors” (n = 51, 40.8%).

Learning outcome

CSA of learning outcomes revealed an increase in the ability to apply the correct diagnostic algorithm to a given case by 74.65% (n = 115). Ability to interpret the findings of diagnostic procedures increased by 70.31% (n = 114).

The end-of-course examination on internal medicine in the fall semester of 2020/21 consisted of 70 questions with a mean score of 85%. 30 (43%) questions have been previously discussed only during ICCD sessions, and 40 questions (57%) only during lectures. ICCD questions were answered with a higher score compared to lecture questions (90.3% vs. 82.4%, p = 0.074). Although not statistically significant, students’ overall performance measured as a grade in the end-of-course examination was improved by material produced during ICCD sessions.

Tutors

15 of 18 eligible tutors (83.33%) completed the survey. One tutor (author JR) conceived the questionnaire and was thus excluded to prevent potential bias.

Tutors rated the introductory seminar as helpful (mean 1.20) and indicated that the concept of the ICCD had been clearly communicated to them (mean 1.07). They did not report extreme difficulties conceiving a clinical case (mean 1.4) and indicated enjoying the process (mean 1.33).

Discussion

This study aimed to report on an undergraduate students´ initiative to facilitate the core curriculum on internal medicine by developing and implementing the novel Integrated Clinical Case Discussions to train cognitive clinical skills relevant to the pertaining lecture. This information can help develop further student-led initiatives to address emergency remote teaching or other perceived curricular deficits with the expressed goal of training cognitive clinical skills.

The direct comparison of ICCDs and lectures versus emergency remote lectures alone revealed tutees´ subjective increased proficiency in clinical reasoning (determining diagnostic algorithm and interpreting findings). Similarly, students´ satisfaction levels rose. Tutees expressed positive feelings about being tutored by peers and high cognitive congruence.

We recorded increased participation rates in the second semester of ICCDs. The participation rate was 44.5% in the first and 71.0% in the second semester respectively. These participation rates merit special consideration, as the compulsory curriculum at TUM fulfils the legally required minimum number of classes and is supplemented with a broad range of voluntary courses (There are another 72 elective and extracurricular courses). This results in a competitive curricular environment in which students may be less intent on yet another learning opportunity, though the ICCDs are the only course covering the full spectrum of the lectures on internal medicine. The above-mentioned and increasing participation rates indicate that there is a target group that welcomes the offer of ICCDs, especially in the second semester on the cardiovascular and hematologic systems. We conclude, that a peer-moderated ICCD in response to emergency remote teaching can improve students´ subjective satisfaction level with learning opportunities and is in line with previous research [36]. Student satisfaction is important to consider, as it is one of the five pillars of Quality Online Education [37] and is positively correlated with student performance [38].

Our results support other studies highlighting the effectiveness of peer-teaching [39, 40] and CCD [41, 42] in teaching cognitive clinical skills. We found that students attending ICCDs in addition to the lecture benefitted from a gain in skill, overall satisfaction, motivation, and knowledge. This aligns with the ICCD´s goal of generating added value to the core curriculum.

Second, we conclude empowering students to organize and execute courses provides an effective way to create custom-tailored and widely accepted teaching formats. The excellent ratings of subjective learning outcomes, educational environment, and cognitive congruence support the notion that student leadership can be useful for curricular development [36, 43, 44].

We described the human and time resources for preparing one ICCD session. With student teachers contributing the most hours to an ICCD we are aware that additional teaching responsibilities might act as an additional stressor on tutors. However, our results suggest that tutors enjoy the process, feel well instructed and mentored in the workflow we proposed. Similarly, previous research has highlighted the benefits of being a peer teacher [10, 45]. Furthermore, students who agree to tutor have been shown to have the necessary resources to cope with the additional stress at their command [46].

It has been repeatedly demonstrated that voluntary courses receive better feedback than compulsory courses [47]. This study was limited by the ICCD´s voluntary nature, too. Selection bias in the evaluation may be introduced by the self-selection of students who are highly motivated to attend an ICCD session on top of the lecture in comparison to those who attended the general lecture alone. The modest overall response rate of 32% also suggests that certain opinions are likely to be overrepresented while others may be missing. However, with the respondent demographics reflecting the general student population at TUM, we believe our study provides worthwhile data. Response rates of approximately 30% have been reported before in the context of voluntary peer teachings [21]. A study by Bahous et al. (2018) suggests that the reliability between voluntary questionnaires with a low response rate and compulsory questionnaires with a high response rate is comparable [48]. To allow for a more comprehensive interpretation of results we also reported the maximum number of possible and de-facto attendances as demonstrated earlier [33]. The study design does not allow for a follow-up to assess the long-term impact on knowledge, skill, and attitude. Since our findings are based on data from one medical school in Germany they cannot be extrapolated to other medical schools without further consideration. However, the German model of medical education being common in Europe, we have reason to believe that study populations at other medical schools may be similar and our findings of value to their curricular designers [49].

Conclusion

Empowering students to design their own add-on learning opportunities can improve learning outcomes, teach clinical reasoning skills beyond the scope of the core curriculum and increase satisfaction ratings with learning opportunities. We believe that our concept provides an easy-to-implement and up-scalable format to alleviate pressure on faculty staff and physicians with teaching capabilities for other schools, too.

For future optimization, we propose to advance the beneficial effect of social and cognitive congruence by inviting lecturers to facilitate ICCD sessions in person as we are now planning at TUM for the fall semester of 2022/23. This ultimately leads to a triangularized teaching format in which a student-tutor moderates the discussion, lecturers support discussions with more in depth-knowledge and clinical experience, and tutees engage in an instructive discussion.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SARS-CoV2:

-

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Type 2

- TUM:

-

Technical University of Munich

- PAL:

-

Peer-assisted learning

- ICCD:

-

Integrated Clinical Case Discussion

- GMTF:

-

German Medical Training Framework

- CCD:

-

Clinical Case Discussion

- SEEQ:

-

Student´s Evaluations of Educational Quality Questionnaire

- CSA:

-

Comparative Self Assessment

References

Choi B, Jegatheeswaran L, Minocha A, Alhilani M, Nakhoul M, Mutengesa E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on final year medical students in the United Kingdom: a national survey. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):206. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02117-1.

Gottenborg E, Yu A, Naderi R, Keniston A, McBeth L, Morrison K, et al. COVID-19’s impact on faculty and staff at a School of Medicine in the US: what is the blueprint for the future? BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):395. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06411-6.

Seifman MA, Fuzzard SK, To H, Nestel D. COVID-19 impact on junior doctor education and training: a scoping review. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2021:postgradmedj-2020–139575. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-139575

Jeong L, Smith Z, Longino A, Merel SE, McDonough K. Virtual Peer Teaching During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Med Sci Educ. 2020:1–2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-01065-1

Ferrel M, Ryan J. The Impact of COVID-19 on Medical Education. Cureus. 2020;12(3). doi:https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7492

Rose S. Medical Student Education in the Time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2131–2. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5227.

Hodges C, Moore S, Lockee B, Trust T, Bond A. The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Educause Review. 2020;2021(July 17).

Topping KJ, Ehly SW. Peer Assisted Learning: A Framework for Consultation. J Educ Psychol Consult. 2009;12(2):113–32. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532768XJEPC1202_03.

Ten Cate O, Durning S. Dimensions and psychology of peer teaching in medical education. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):546–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701583816.

Yu T-C, Wilson NC, Singh PP, Lemanu DP, Hawken SJ, Hill AG. Medical students-as-teachers: a systematic review of peer-assisted teaching during medical school. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2011;2:157–72. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S14383.

Ten Cate O, Durning S. Peer teaching in medical education: twelve reasons to move from theory to practice. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):591–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701606799.

Schuetz E, Obirei B, Salat D, Scholz J, Hann D, Dethleffsen K. A large-scale peer teaching programme – acceptance and benefit. The Journal of Evidence and Quality in Health Care. 2017;125:71–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zefq.2017.05.026.

Keifenheim KE, Petzold ER, Junne F, Erschens RS, Speiser N, Herrmann-Werner A, et al. Peer-Assisted History-Taking Groups: A Subjective Assessment of their Impact Upon Medical Students' Interview Skills. GMS J Med Educ. 2017;34(3):Doc35-Doc. doi:https://doi.org/10.3205/zma001112

Blank WA, Blankenfeld H, Vogelmann R, Linde K, Schneider A. Can near-peer medical students effectively teach a new curriculum in physical examination? BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1):165. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-13-165.

Graziano SC. Randomized surgical training for medical students: resident versus peer-led teaching. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011;204(6):542.e1-.e4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.038

Hughes TC, Jiwaji Z, Lally K, Lloyd-Lavery A, Lota A, Dale A, et al. Advanced Cardiac Resuscitation Evaluation (ACRE): a randomised single-blind controlled trial of peer-led vs. expert-led advanced resuscitation training. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2010;18:3-. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-7241-18-3

Engels D, Kraus E, Obirei B, Dethleffsen K. Peer teaching beyond the formal medical curriculum. Adv Physiol Educ. 2018;42(3):439–48. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00188.2017.

Schmid SC, Berberat PO, Gschwend JE, Autenrieth ME. Praktische Studentenausbildung in der Urologie. Urologe. 2014;53(4):537–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00120-014-3435-2.

Bussey-Jones J, Bernstein L, Higgins S, Malebranche D, Paranjape A, Genao I, et al. Repaving the Road to Academic Success: The IMeRGE Approach to Peer Mentoring. Acad Med. 2006;81(7):674–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.Acm.0000232425.27041.88.

Koenemann N, Lenzer B, Zottmann JM, Fischer MR, Weidenbusch M. Clinical Case Discussions - a novel, supervised peer-teaching format to promote clinical reasoning in medical students. GMS J Med Educ. 2020;37(5):Doc48-Doc. doi:https://doi.org/10.3205/zma001341

Bulte C, Betts A, Garner K, Durning S. Student teaching: views of student near-peer teachers and learners. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):583–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701583824.

Biesma R, Kennedy M-C, Pawlikowska T, Brugha R, Conroy R, Doyle F. Peer assessment to improve medical student’s contributions to team-based projects: randomised controlled trial and qualitative follow-up. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):371. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1783-8.

Thomas PA, Kern DE, Hughes MT, Chen BY. Curriculum development for medical education: a six-step approach: JHU Press; 2016.

Crosby RMHJ. AMEE Guide No 20: The good teacher is more than a lecturer - the twelve roles of the teacher. Med Teach. 2000;22(4):334–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/014215900409429.

Nationaler Kompetenzbasierter Lernzielkatalog Medizin. Medizinischer Fakultätentag. 2021. https://nklm.de/zend/menu.

Richards PS, Inglehart MR. An Interdisciplinary Approach to Case-Based Teaching: Does It Create Patient-Centered and Culturally Sensitive Providers? J Dent Educ. 2006;70(3):284–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.0022-0337.2006.70.3.tb04084.x.

Linsenmeyer M. Brief Activities: Questioning, Brainstorming, Think-Pair-Share, Jigsaw, and Clinical Case Discussions. In: Fornari A, Poznanski A, editors. How-to Guide for Active Learning. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 39–66.

Ertmer PA, Newby TJ. Behaviorism, Cognitivism, Constructivism: Comparing Critical Features from an Instructional Design Perspective. Perform Improv Q. 1993;6(4):50–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-8327.1993.tb00605.x.

Marsh H. SEEQ: A Reliable, Valid, and Useful Instrument for Collecting Students´ Evaluations of University Teaching. Br J Educ Psychol. 1982;52:77–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1982.tb02505.x.

Vennemann S, Holzmann-Littig C, Marten-Mittag B, Vo Cong M, Berberat P, Stock K. Short- and Long-Term Effects on Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes About a Sonography Training Concept for Medical Students. Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography. 2020;36(1):25–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/8756479319878394.

Grave WSD, Dolmans DHJM, Vleuten CPMvd. Tutor intervention profile: reliability and validity. Med Educ. 1998;32(3):262–8. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00226.x.

Ginns P, Prosser M, Barrie S. Students’ perceptions of teaching quality in higher education: the perspective of currently enrolled students. Stud High Educ. 2007;32(5):603–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070701573773.

Raupach T, Münscher C, Beißbarth T, Burckhardt G, Pukrop T. Towards outcome-based programme evaluation: Using student comparative self-assessments to determine teaching effectiveness. Med Teach. 2011;33(8):e446–53. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2011.586751.

Lenzner T, Menold N. Frageformulierung. In: Sozialwissenschaften GL-If, editor. GESIS Survey Guidelines. Mannheim2015.

Mayring P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. In: Mey G, Mruck K, editors. Handbuch Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2010. p. 601–13.

Dohle NJ, Machner M, Buchmann M. Peer teaching under pandemic conditions – options and challenges of online tutorials on practical skills. GMS J Med Educ. 2021;38(1):Doc7. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma001403.

Lorenzo GM, Janet The Sloan Consortium Report to the Nation FIVE PILLARS OF QUALITY ONLINE EDUCATION: The Sloan Consortium2002 November 2002.

Rajabalee YB, Santally MI. Learner satisfaction, engagement and performances in an online module: Implications for institutional e-learning policy. Educ Inf Technol. 2021;26(3):2623–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10375-1.

Benè KL, Bergus G. When learners become teachers: a review of peer teaching in medical student education. Fam Med. 2014;46(10):783–7.

Bouwmeester RAM, de Kleijn RAM, van Rijen HVM. Peer-instructed seminar attendance is associated with improved preparation, deeper learning and higher exam scores: a survey study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):200. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0715-0.

Bi M, Zhao Z, Yang J, Wang Y. Comparison of case-based learning and traditional method in teaching postgraduate students of medical oncology. Med Teach. 2019;41(10):1124–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2019.1617414.

Burgess A, Matar E, Roberts C, Haq I, Wynter L, Singer J, et al. Scaffolding medical student knowledge and skills: team-based learning (TBL) and case-based learning (CBL). BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):238. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02638-3.

Burk-Rafel J, Harris KB, Heath J, Milliron A, Savage DJ, Skochelak SE. Students as catalysts for curricular innovation: A change management framework. Med Teach. 2020;42(5):572–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1718070.

den Bakker CR, Hendriks RA, Houtlosser M, Dekker FW, Norbart AF. Twelve tips for fostering the next generation of medical teachers. Medical Teacher. 2021:1–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2021.1912311

Shenoy A, Petersen KH. Peer Tutoring in Preclinical Medical Education: A Review of the Literature. Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(1):537–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-019-00895-y.

Hundertmark J, Alvarez S, Loukanova S, Schultz J-H. Stress and stressors of medical student near-peer tutors during courses: a psychophysiological mixed methods study. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1521-2.

Aleamoni LM. Student Rating Myths Versus Research Facts from 1924 to 1998. J Pers Eval Educ. 1999;13(2):153–66. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008168421283.

Aoun Bahous S, Salameh P, Salloum A, Salameh W, Park YS, Tekian A. Voluntary vs. compulsory student evaluation of clerkships: effect on validity and potential bias. BMC Medical Education. 2018;18(1):9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1116-8

Wijnen-Meijer M, van den Broek M, ten Cate O. Six Routes to Unsupervised Clinical Practice. Acad Med. 2021;96(3):475. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003880.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all our tutors for their outstanding engagement and continuous feedback on improving ICCD as well as all the people who have provided useful productive feedback on earlier manuscripts. We would particularly like to thank the reviewers of this article for their encouragement and highly detailed feedback.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was kindly supported by the Technical University of Munich under a grant for teaching-related projects of excellence at Technical University of Munich (TUM) (“Studienbezogene Exzellenstrategie der TUM”) and partly under a fund jointly handled by student representatives and the TUM Medical Education Center (“Planungsmittelkommission”).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JR conceived the didactic concept of the ICCD, developed the questionnaire, and oversaw the data acquisition. NS was chief exchequer, head of human resources, and coordinated cooperation with the lecturers. TW developed administered the online material, zoom-links, and monitored student commentaries for continuous improvement. CHL helped with conceiving the evaluation tool and data analysis. VP matched lecturers to the ICCD sessions, facilitated their communication with the tutors, and majorly revised the manuscript. MWM conducted the didactic lecture and majorly revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Authors’ information

At the time of the study the following statements apply:

Johannes Reifenrath is a fifth-year medical student at Technical University of Munich, School of Medicine, and a student representative to the school´s committee on curricular development.

Nick Luca Seiferth is a fifth-year medical student at Technical University of Munich, School of Medicine, and a student envoy to the school´s faculty council.

Theresa Wilhelm is a sixth-year medical student at Technical University of Munich, School of Medicine, and a student representative to the school´s committee on curricular development.

Christopher Holzmann-Littig, MD, is a resident at Technical 482 University, School of Medicine, Department of Nephrology, and a 483 member of TUM Medical Education Center.483 member of TUM Medical Education Center.

Veit Phillip, MD, Instructor of Medicine, is a senior physician at Technical University, School of Medicine, Department of Gastroenterology and coordinates the lectures on internal medicine.

Marjo Wijnen-Meijer is head of innovation at the TUM Medical Education Center and specializes in curricular development.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from each participant and monitored and approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Technical University of Munich (grant number 701/20S).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Appendix Table 1. Cognitive Congruence and Educational Environment. The table gives an overview of the items used to compute the cognitive congruence between tutors and tutees using the mean of section “1. Cognitive Congruence”, where 1 denotes the greatest and 5 the lowest level of tutees´ satisfaction. Tutees´ perception of the educational environment was computed by calculating the mean of the items in section “2. Educational Environment”. Cronbach´s alpha for cognitive congruence was 0.76; for educational environment 0.83.

Mean | Mode | Std. Deviation | participants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1. Cognitive Congruence | ||||

The tutor states learning objectives clearly | 1.25 | 1.00 | 0.49 | 292 |

The tutor stresses relevant points | 1.19 | 1.00 | 0.43 | 293 |

The tutor was able to explain complex matters clearly | 1.23 | 1.00 | 0.46 | 293 |

The tutor acknowledges challenges | 1.31 | 1.00 | 0.54 | 291 |

The tutor answers questions clearly | 1.37 | 1.00 | 0.68 | 293 |

2. Educational Environment | ||||

The tutor incentivizes participation | 1.37 | 1.00 | 0.63 | 290 |

The tutorial has helped me connect new input to prior knowledge | 1.23 | 1.00 | 0.46 | 291 |

The tutor creates space for practicing the contents of the tutorial | 1.27 | 1.00 | 0.49 | 292 |

The atmosphere was pleasant and supportive | 1.16 | 1.00 | 0.39 | 293 |

I feel it is okay to make a mistake | 1.47 | 1.00 | 0.72 | 293 |

The tutor and other tutees showed respect and appreciation for my contributions | 1.41 | 1.00 | 0.76 | 277 |

If at all, I was criticized respectfully | 1.32 | 1.00 | 0.61 | 280 |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Reifenrath, J., Seiferth, N., Wilhelm, T. et al. Integrated clinical case discussions – a fully student-organized peer-teaching program on internal medicine. BMC Med Educ 22, 828 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03889-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03889-4