Abstract

Background

Computer-assisted navigation (CAS) was developed to improve the surgical accuracy and precision. Many studies demonstrated better alignment in the coronal plane in CAS TKA compared to conventional technique. The influence on the functional outcome is still unclear. Only few studies report long-term results of CAS TKA. This study was initiated to investigate 10-year patient-reported outcome of CAS and conventional TKA.

Methods

From initially 80 patients of a randomized study of CAS and conventional TKA a total of 50 patients could be evaluated at the 10-year follow-up. The Knee Society Score and EuroQuol Questionnaire were assessed. For all patients a competing risk analysis for revision was performed.

Results

The patient-reported outcome measures demonstrated similar values for both groups. The 10-year risk for revision was 2.5% for conventional TKA and 7.5% for CAS TKA (p=0.237).

Conclusions

There was no difference between CAS and conventional TKA with regard to patient-reported outcome and revision risk ten years after surgery.

Trial registration

This study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov on 11/30/2009, ID: NCT01022099.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a very effective treatment option for end-stage ostearthritis of the knee. The influence of knee alignment on outcome and revision rates after TKA has been debated controversially. While some studies demonstrated an increased revision risk in malaligned TKA [1, 2] other studies did not find a difference between TKA with a mechanical axis within or outside 0 ± 3° [3,4,5]. Furthermore, since the concepts of constitutional varus [6] and kinematic alignment [7] were introduced a neutral leg alignment is not always desired. Although the ideal leg axis is still under discussion, the individually planned alignment should be achieved and a relevant malalignment should be avoided [8, 9].

Computer-assisted navigation (CAS) was developed to improve the surgical accuracy and precision. In systematic reviews, many studies demonstrated better alignment in the coronal plane in CAS TKA compared to conventional technique [10, 11] but did not improve rotational alignment [12]. It has been expected that this improved accuracy will result in better patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and reduced revision rates. Studies investigating mid-term PRO demonstrated mostly similar results between CAS and conventional TKA. Only few studies report long-term results of CAS TKA. Some of these studies demonstrated better long-term survival of CAS TKA [13,14,15,16]. Additional advantages of CAS TKA are the more accurate and more effective soft-tissue balancing due to the direct response from the CAS system. Furthermore, CAS is a valuable measuring and teaching tool. Disadvantages of computer navigation include increased costs, longer operating time, the risk of fractures around pin sites and pin site infection. However, the overall risk of CAS-specific complications has been described as very low [17]. To date the role of CAS TKA is still under debate [18].

This study was initiated to investigate the long-term patient-reported outcome of CAS and conventional TKA. We hypothesized better PROMs in CAS TKA.

Methods

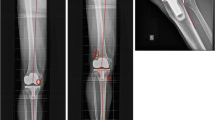

This is a follow up study on a previously puplished prospective randomized clinical trial [19,20,21].A total of 80 patients scheduled for TKA between January 2006 and April 2007 were randomized to CAS or conventional surgical technique after informed consent. All patients were operated by two surgeons experienced in both techniques, conventional and CAS TKA (SK, JL). Both surgeons have performed at least 30 CAS TKA before the study. All patients received the same cemented, unconstrained, cruciate-retaining TKA with a rotating platform (Scorpio PCS, Stryker, Mahwah, NJ, USA) without patellar resurfacing. All surgeries were performed using a medial patellofemoral approach and a femur-first measured resection technique. Soft-tisue balancing was performed after the bone cuts. All surgeries aimed at a neutral leg axis (mechanical alignment). In the CAS group an imageless navigation system was used (Stryker navigation, Stryker, Mahwah, NJ).

Patients were seen by a trained study nurse before surgery, at 2, 5 and 10 years and knee function and health-related quality of life (HrQoL) were obtained using the Knee Society Score (KSS) and the EuroQuol questionnaire (EQ-5D). The KSS is divided into a Knee Score and a Function Score. The Knee Score consists of items on pain, range of motion, stability and alignment of the leg, the Function Score includes information on walking distance, stair climbing and walking aids. In both scores a total of 100 points indicates full function. The EQ-5D describes the self-perceived health state of the patient using subgroups of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression. The subgroups are divided into three levels (no problems, some problems, serious problems/unable to perform). From these answers an index can be calculated in which 0 indicates the worst and 1.0 the best HrQoL. Additionally, a visual analogue scale (VAS) records the patient`s current health state. A value of 100 indicates the best and a value of 0 indicates the worst imaginable health state.

The study protocol for the long-term follow-up was approved by the local independent ethics committee in March, 2011 (EK6012011). Study follow-up was completed in May 2017 as the study ended regularly.

Statistical analysis

Endpoints of this investigation were differences between the two groups in knee function (Knee Society Score) or in self-perceived general health state (EQ-5D). Due to low case number and not normally distributed data, description was based on medians and inter-quartile ranges for continuous values and on absolute and relative frequencies for categorical endpoints, respectively. Comparisons between groups were based on two sample Wilcoxon tests for continuous endpoints and on Fisher`s exact tests for categorical endpoints, respectively. Results of these exploratory significance tests were summarized in p-values, where p<0.05 indicates statistically significant differences between groups. All analyses were performed using SPSS® software (release 24.0 for Windows®, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

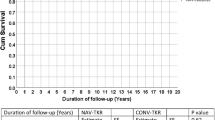

To estimate the risk of revision, the cumulative incidence function, which takes account of death as a competing risk, was used. Survival data were analysed using the statistical software R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

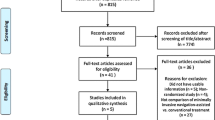

Fourteen patients died before the 10-year follow-up. Twelve of the remaining patients did not return for a follow-up visit: two patients could not be contacted, six were unable to attend the follow-up examination due to illness unrelated to the knee arthroplasty and four refused to attend (Fig. 1).

There were fewer outliers outside a range of 3° from a neutral leg axis in the navigated group, but this difference was not statistically significant. There were no statistically significant differences in coronal, sagittal or rotational alignment of the femoral and tibial components between the two groups [21].

Four patients had undergone revision: one patient from the conventional group due to a preoperatively unknown metallic hypersensitivity with persistent swelling one year after surgery and three patients of the CAS group (one each for aseptic loosening after eight years, instability after nine years and periprosthetic infection after nine years). The 10-year risk for revision (all causes) was 2.5% for conventional TKA and 7.5% for CAS TKA using competing risk survival analysis (p=0.237).

Further reoperations included one secondary patellar resurfacing four years after surgery, one periprosthetic femur fracture which was treated by open reduction and internal fixation (both in the conventional group) and two acute periprosthetic infections in the CAS group (5 and 7.5 years after primary surgery) which were successfully treated with debridement, irrigation, insert exchange and antibiotics (DAIR).

The remaining patients in both groups were still comparable at baseline for age, sex, comorbidities (ASA-Score) and body mass index (BMI, Table 1).

The Knee Society Score showed lower values pre-operatively in the navigated group and similar results to the conventional group at the 2, 5 and 10-year follow-up. For both groups no relevant decrease in the Knee Score could be noted, whereas the Function Score decreased after 5 years (Fig. 2)

Health related quality of life increased up to two years after TKA, then slightly decreased. No significant differences have been observed between the two groups (Table 2).

Discussion

Long-term follow-up after ten years demonstrated in the present study similar patient-reported outcome measures and revision rates in CAS and conventional TKA.

The overall all-cause revision risk was 5% for all patients which is consistent with results of major arthroplasty registries [22,23,24]. There was no significant difference in the revision rates between both groups, which is consistent with most long-term studies comparing CAS and conventional TKA (Table 3). There is only one prospective study which demonstrated superior survival of CAS TKA [14]. This study included the learning curve as the surgeon had no prior experience with TKA and the results may therefore not be applicable to the majority of arthroplasty surgeons. Another study from the Australian registry demonstrated significant fewer revisions in patients aged less than 65 years at the time of surgery [13]. This might be one reason that the use of Computer-navigation in Australia has increased distinctly and was 33.5% in the 2018 report. This advantage of CAS TKA in the younger patients still existed in the latest report [24] (cumulative risk of revision in patients <65 years at 10/15 years: CAS 6.6% / 9.6%, conventional 7.7% / 11.1%). There was no difference in patients aged 65 years and older. In other prospective studies [25,26,27,28,29], revision rates were mostly higher in the conventional group although not statistically significant, which might be due to the limited number of patients. In two retrospective studies [15, 16], with a larger number of patients there was a significant better survival in the CAS TKA group. However, in both studies only less than 50% of the patients have been followed until ten years, which together with the retrospective design limits the validity of these data considerably.

Functional outcome measured with the Knee Society Score was not different between both groups at any follow-up in this study. This might be influenced by the fact that the aimed mechanical alignment was similar in both groups. It is, however, consistent with all other prospective studies with long-term follow-up [25,26,27,28,29]. Health-related quality of life demonstrated lower improvement but equivalent values when compared to an age-adapted standard population [30]. There were no differences between both groups in the present study.

Patient-reported outcome after TKA depends on several additional factors including rotational alignment, soft tissue-balance, the patello-femoral joint and especially patient-specific factors which might be even more important than leg axis and implant alignment. CAS TKA does not result in better rotational alignment [12] and it is not known whether the use of computer-navigation may influence patellar tracking. Several studies demonstrated that soft-tissue balancing can be more accurate and effective in CAS TKA [31,32,33,34]. This could not be investigated in detail in this study because a measured resection technique was used. However, patient-specific factors may have an even stronger correlation with functional results than intraoperative data which may be positively influenced by the use of a navigation system (alignment, ligament balance, range of motion) [35, 36]. Finally, TKA is a very effective procedure in terms of functional improvement and improvement in health-related quality of life. It is therefore difficult to further improve these results by any technology. Currently, despite better alignment, there is no evidence that Computer-navigation results in better patient-reported outcome measures.

The main limitation of this study is the relevant number of patients, which could not be followed until ten years after surgery. This is unfortunately common in these older patients. Only 50 from initially 80 patients (62.5%) were available for the 10-year follow-up, which limits the significance of the clinical results due to small group sizes.

Conclusion

There was no difference between CAS and conventional TKA with regard to patient-reported outcome and revision risk ten years after surgery.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to third party rights but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CAS:

-

Computer-assisted navigation

- EQ-5D:

-

EuroQuol questionnaire

- HrQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- KSS:

-

Knee Society Score

- PRO:

-

Patient-reported Outcome

- TKA:

-

Total knee arthroplasty

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

References

Berend ME, Ritter MA, Meding JB, Faris PM, Keating EM, Redelman R, et al. Tibial component failure mechanisms in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;428:26–34.

Ritter MA, Davis KE, Davis P, Farris A, Malinzak RA, Berend ME, et al. Preoperative malalignment increases risk of failure after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(2):126–31.

Parratte S, Pagnano MW, Trousdale RT, Berry DJ. Effect of postoperative mechanical axis alignment on the fifteen-year survival of modern, cemented total knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(12):2143–9.

Matziolis G, Adam J, Perka C. Varus malalignment has no influence on clinical outcome in midterm follow-up after total knee replacement. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130(12):1487–91.

Tibbo ME, Limberg AK, Perry KI, Pagnano MW, Stuart MJ, Hanssen AD, et al. Effect of Coronal Alignment on 10-Year Survivorship of a Single Contemporary Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Clin Med. 2021;10(1):142.

Bellemans J, Colyn W, Vandenneucker H, Victor J. The Chitranjan Ranawat award: is neutral mechanical alignment normal for all patients? The concept of constitutional varus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(1):45–53.

Howell SM, Howell SJ, Kuznik KT, Cohen J, Hull ML. Does a kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty restore function without failure regardless of alignment category? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(3):1000–7.

Abdel MP, Oussedik S, Parratte S, Lustig S, Haddad FS. Coronal alignment in total knee replacement: historical review, contemporary analysis, and future direction. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(7):857–62.

Oussedik S, Abdel MP, Victor J, Pagnano MW, Haddad FS. Alignment in total knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2020;102-B(3):276–9.

Rebal BA, Babatunde OM, Lee JH, Geller JA, Patrick DA Jr, Macaulay W. Imageless computer navigation in total knee arthroplasty provides superior short term functional outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Arthroplast. 2014;29(5):938–44.

Matsumoto T, Nakano N, Lawrence JE, Khanduja V. Current concepts and future perspectives in computer-assisted navigated total knee replacement. Int Orthop. 2018;43(6):1337–43.

Meijer MF, Reininga IH, Boerboom AL, Bulstra SK, Stevens M. Does imageless computer-assisted TKA lead to improved rotational alignment or fewer outliers? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(10):3124–33.

de Steiger RN, Liu YL, Graves SE. Computer navigation for total knee arthroplasty reduces revision rate for patients less than sixty-five years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(8):635–42.

Lacko M, Schreierova D, Cellar R, Vasko G. Long-Term Results of Computer-Navigated Total Knee Arthroplasties Performed by Low-Volume and Less Experienced Surgeon. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cechoslov. 2018;85(3):219–25.

Baumbach JA, Willburger R, Haaker R, Dittrich M, Kohler S. 10-Year Survival of Navigated Versus Conventional TKAs: A Retrospective Study. Orthopedics. 2016;39(3 Suppl):S72–6.

Baier C, Wolfsteiner J, Otto F, Zeman F, Renkawitz T, Springorum HR, et al. Clinical, radiological and survivorship results after ten years comparing navigated and conventional total knee arthroplasty: a matched-pair analysis. Int Orthop. 2017;41(10):2037–44.

Khakha RS, Chowdhry M, Norris M, Kheiran A, Chauhan SK. Low incidence of complications in computer assisted total knee arthroplasty--A retrospective review of 1596 cases. Knee. 2015;22(5):416–8.

Jones CW, Jerabek SA. Current Role of Computer Navigation in Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2018;33(7):1989–93.

Lützner J, Dexel J, Kirschner S. No difference between computer-assisted and conventional total knee arthroplasty: five-year results of a prospective randomised study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(10):2241–7.

Lützner J, Günther K-P, Kirschner S. Functional outcome after computer-assisted versus conventional total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(10):1339–44.

Lützner J, Krummenauer F, Wolf C, Günther K-P, Kirschner S. Computer-assisted and conventional total knee replacement: a comparative, prospective, randomised study with radiological and CT evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(8):1039–44.

Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register: Annual Report 2020. https://www.myknee.se/en/. Accessed 9 Aug 2021.

National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man: 17th Annual Report 2020. https://reports.njrcentre.org.uk/downloads. Accessed 9 Aug 2021.

Australien Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry: Annual Report 2020. https://aoanjrr.sahmri.com/annual-reports-2020. Accessed 9 Aug 2021.

Cip J, Obwegeser F, Benesch T, Bach C, Ruckenstuhl P, Martin A. Twelve-Year Follow-Up of Navigated Computer-Assisted Versus Conventional Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Prospective Randomized Comparative Trial. J Arthroplast. 2018;33(5):1404–11.

d'Amato M, Ensini A, Leardini A, Barbadoro P, Illuminati A, Belvedere C. Conventional versus computer-assisted surgery in total knee arthroplasty: comparison at ten years follow-up. Int Orthop. 2019;43(6):1355–63.

Kim YH, Park JW, Kim JS. The Clinical Outcome of Computer-Navigated Compared with Conventional Knee Arthroplasty in the Same Patients: A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind, Long-Term Study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(12):989–96.

Ouanezar H, Franck F, Jacquel A, Pibarot V, Wegrzyn J. Does computer-assisted surgery influence survivorship of cementless total knee arthroplasty in patients with primary osteoarthritis? A 10-year follow-up study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(11):3448–56.

Song EK, Agrawal PR, Kim SK, Seo HY, Seon JK. A randomized controlled clinical and radiological trial about outcomes of navigation-assisted TKA compared to conventional TKA: long-term follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(11):3381–6.

Szende A, Janssen B, Cabases J. Self-reported population health: an international perspective based on EQ-5D: Springer Netherlands Dordrecht; 2014.

Lee D-H, Park J-H, Song D-I, Padhy D, Jeong W-K, Han S-B. Accuracy of soft tissue balancing in TKA: comparison between navigation-assisted gap balancing and conventional measured resection. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(3):381–7.

Walde T, Bussert J, Sehmisch S, Balcarek P, Stürmer K, Walde H, et al. Optimized functional femoral rotation in navigated total knee arthroplasty considering ligament tension. Knee. 2010;17(6):381–6.

Lee HJ, Lee JS, Jung HJ, Song KS, Yang JJ, Park CW. Comparison of joint line position changes after primary bilateral total knee arthroplasty performed using the navigation-assisted measured gap resection or gap balancing techniques. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(12):2027–32.

Pang H-N, Yeo S-J, Chong H-C, Chin P-L, Ong J, Lo N-N. Computer-assisted gap balancing technique improves outcome in total knee arthroplasty, compared with conventional measured resection technique. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(9):1496–503.

Lützner C, Postler A, Beyer F, Kirschner S, Lützner J. Fulfillment of expectations influence patient satisfaction 5 years after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(7):2061–70.

Widmer BJ, Scholes CJ, Lustig S, Conrad L, Oussedik SI, Parker DA. Intraoperative computer navigation parameters are poor predictors of function 1 year after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2013;28(1):56–61.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Brit Brethfeld for her valuable assistance during follow-up.

Funding

This study was funded by Stryker Orthopaedics (grant number GWT 7878). The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SK and JL have been involved in planning and in the execution, FB, CL and JL in the analysis of this study. FB and AP have written the draft and all authors have corrected and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol for the long-term follow-up was approved by the local independent ethics committee (Ethikkommission an der Technischen Universität Dresden) in March, 2011 (EK6012011). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Consent for publication

n.a.

Competing interests

JL has received research grants from Aesculap, Link, Mathys, Smith&Nephew and BiometZimmer and honoraria for workshops from Aesculap, Link, Mathys and Pfizer outside the submitted work. SK has received research grants from Stryker and BiometZimmer and honoraria from Smith&Nephew outside the submitted work. All other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Beyer, F., Pape, A., Lützner, C. et al. Similar outcomes in computer-assisted and conventional total knee arthroplasty: ten-year results of a prospective randomized study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22, 707 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04556-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04556-3