Abstract

Background

Rare cases of COVID-19 infection- and vaccine-triggered autoimmune diseases have been separately reported in the literature. In this paper, we report the first and unique case of new onset acute psychosis as a manifestation of lupus cerebritis following concomitant COVID-19 infection and vaccination in a previously healthy 26-year-old Tunisian female.

Case presentation

A 26-years old female with a family history of a mother diagnosed with schizophrenia, and no personal medical or psychiatric history, was diagnosed with mild COVID-19 infection four days after receiving the second dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. One month after receiving the vaccine, she presented to the psychiatric emergency department with acute psychomotor agitation, incoherent speech and total insomnia evolving for five days. She was firstly diagnosed with a brief psychotic disorder according to the DSM-5, and was prescribed risperidone (2 mg/day). On the seventh day of admission, she reported the onset of severe asthenia with dysphagia. Physical examination found fever, tachycardia, and multiple mouth ulcers. Neurological evaluation revealed a dysarthria with left hemiparesis. On laboratory tests, she had severe acute kidney failure, proteinuria, high CRP values, and pancytopenia. Immune tests identified the presence of antinuclear antibodies. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed hyperintense signals in the left fronto-parietal lobes and the cerebellum. The patient was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and put on anti-SLE drugs and antipsychotics, with a favorable evolution.

Conclusions

The chronological relationship between COVID-19 infection, vaccination and the first lupus cerebritis manifestations is highly suggestive, albeit with no certainty, of the potential causal link. We suggest that precautionary measures should be taken to decrease the risk of SLE onset or exacerbation after COVID-19 vaccination, including a systematic COVID-19 testing before vaccination in individuals with specific predisposition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

So far, the coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused substantial morbidity and mortality rates around the globe. While most often presenting as flu-like symptoms, other severe manifestations and complications underpinned by the cytokine release storm (CRS) may occur. This engenders a marked upsurge of systemic inflammation and an acute severe immune-response, which may in turn lead to the exacerbation or even emergence of autoimmune disorders [1]. In an attempt to create an immune barrier among population and attenuate the spread of the virus, various vaccines have been timely developed and have been shown to be safe and effective in the majority of populations vaccinated. Nevertheless, rare adverse effects have recently been reported, including the triggering of autoimmune diseases [2]. Therefore, autoimmune diseases induced by both infection and vaccination have become a serious concern.

A challenging autoimmune disease is systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). One hypothesized etiology for the development of SLE is viral [3]. Viral agents (e.g., Epstein–Barr virus, parvovirus B19, retroviruses and cytomegalovirus) have been suggested to trigger immune reactions against the self-antigens, thus leading to autoimmunity [3]. In this regard, some authors have also reported cases of SLE manifesting after COVID-19 infection in a 39-year-old Iranian/Persian man [4], a 32-year-old Kenyan woman [5], an 85-year-old Italian woman [6], and a 38 year old Iranian woman [7]. Both SLE and COVID-19 are characterized by a complex clinical manifestation; and share similar disease characteristics including multi-organ complications (e.g., arthralgia, cytopenia, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, interstitial pneumonia, and myocarditis) [8]. In addition, both diseases affect the Central Nervous System and may manifest as neuropsychiatric symptoms (known as lupus cerebritis and neuro-COVID); with psychosis being amongst the least uncommon and most dreaded neuropsychiatric manifestations of SLE [9] and COVID-19 [10]. Herein, we report the first and unique case of new onset acute psychosis as a manifestation of lupus cerebritis following both COVID-19 infection and vaccination in a previously healthy 26-year-old Tunisian female. We then discuss possible mechanisms linking these two entities and potential therapeutic approaches based on the literature.

Written consent for publication from the patient

Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for the use and publication of the clinical data and results from clinical examinations for research.

Case presentation

A 26-years old female with a family history of a mother diagnosed with schizophrenia, and no personal medical or psychiatric history, was diagnosed with mild COVID-19 infection by nasopharyngeal and throat swab reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), four days after receiving the second dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. She was asymptomatic when she received the COVID-19 vaccine. Two weeks later, she presented to the emergency department with chest pain, where physical examination revealed a heart rate of 110/min. A cardiac ultrasound examination showed a pericardial effusion suggestive of pericarditis. She was started on aspirin and colchicine, with a slow recovery.

One month after receiving the vaccine, she presented to the psychiatric emergency department with acute psychomotor agitation, incoherent speech and total insomnia evolving for five days. She had no recent history of trauma, and no lifetime history of substance use. Routine investigations were done to rule out a differential diagnosis of psychosis according to first signs and the clinical examination, such as cerebrovascular (e.g., stroke, subdural hematomas, cerebral tumors), seizure (e.g., partial complex seizures, temporal lobe epilepsy), metabolic (e.g., phaeochromocytoma), infectious (neurosyphilis, HIV), and endocrine (dysthyroïdism) disorders [11]. Precisely, laboratory tests (including thyroid blood tests and syphilis/HIV serologies) showed an isolated mild anemia. Her electroencephalographic (EEG) and CT brain-scan found no abnormalities. She, and her family members, denied any substance use. She was admitted to our psychiatric unit, where psychiatric examination revealed severe anxiety, delusions of persecution and reference, auditory hallucinations, disorganized speech and behavior. The patient had no delirium symptoms and a lack of insight. Her neurological examination was normal. She was started on intramuscular haloperidol 10 mg/ day and diazepam 10 mg/day. There was a complete resolution of psychotic symptoms within four days of treatment initiation. She was thus diagnosed with a brief psychotic disorder according to the DSM-5 [12], and was prescribed risperidone (2 mg/day).

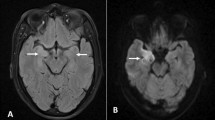

On the seventh day of admission, while her discharge has been planned and discussed with the family, she reported the onset of severe asthenia with dysphagia. Physical examination found fever (body temperature of 40 degrees Celsius), tachycardia (heart rate of 123 beats/min), and multiple mouth ulcers. Thoracic auscultation found normal lung and heart sound. A second neurological evaluation revealed a dysarthria with left hemiparesis, evoking an acute stroke. Another psychiatric examination found a concomitant relapse of psychiatric symptoms. On laboratory tests, she had severe acute kidney failure, proteinuria, high CRP values, and pancytopenia. Infectious investigation was negative. The SARS-CoV-2 PCR with nasopharyngeal swab was negative. Chest X-ray showed bilateral pleural effusion. Immune tests identified the presence of antinuclear antibodies. The anti-ENA (extractable nuclear antigen) antibody screen showed strongly positive anti-SSA, anti-Ro52, anti-SSB, as well as weakly positive anti-nucleosome, and anti-histone antibodies. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed hyperintense signals in the left fronto-parietal lobes and the cerebellum (Fig. 1). Based on these clinical and laboratory evidence, the patient was diagnosed with SLE according to the 2019 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism (ACR/EULAR) classification criteria [13]. She was then transferred to the internal medicine department and put on Hydroxychloroquine (400 mg daily), prednisone (40 mg daily), Cyclophosphamide (1 g monthly) and risperidone (2 mg daily). Both the SLE and psychotic symptoms improved within one month, and she was discharged. During outpatient follow-up, she was free from neurological and psychiatric symptoms and had good tolerance to treatment.

Discussion

In this paper, we describe to our knowledge the first case of lupus cerebritis manifesting as new-onset acute psychosis 3 to 4 weeks following both COVID-19 infection and vaccination in a young female adult with no previous medical or psychiatric history. It is worth mentioning that the patient had one episode of acute pericarditis around two weeks after the COVID-19 infection, and two weeks prior to the onset of the acute psychosis. She also had an acute stroke. Both pericarditis and stroke can either be due to the COVID-19 [14, 15], or to SLE [16, 17]. We could find only one case report of lupus cerebritis occurring three weeks after COVID-19 infection in a 29-year-old female with a past medical history of SLE, and which manifested as slow speech, psychomotor agitation, and intermittent choreiform movements in the upper part of the body [18]. The existing new-onset SLE cases reported in the literature developed either concurrently with COVID-19 infection, or within one to six weeks after infection/vaccination (see Table 1).

Acute psychosis as the first and main presenting manifestation of SLE is rarely encountered in clinical practice [19]. The etiopathogenesis of psychosis due to neuro-lupus is multifactorial, yet complex and unclear [20]. The two main, and likely complementary proposed mechanisms are (1) autoimmune/ inflammatory and (2) ischemic or thrombotic pathways [20, 21]. The autoimmune-mediated neuro-inflammatory pathway involves an increased permeability of the blood-brain barrier, with neuronal autoantibodies intrathecal migration and intracranial generation of pro-inflammatory mediators (cytokines and others) [20]. As for the ischemic pathway, it originates in cerebral micro-angiopathy, which is mediated by immune complexes, antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies, and complement activation [20].

Although psychosis has been widely reported as a lupus-related phenomenon and as a well-established manifestation of lupus cerebritis, the association between psychosis and SLE in the present case deserves to be deeply discussed. Some hypotheses seem plausible. The first hypothesis is a possible direct role of viral infection on the concomitant but fortuitous occurrence of SLE [3] and psychosis [22] in a genetically loaded young adult (i.e. family history of schizophrenia). However, it is difficult and premature to conclude whether a direct and causal link exists between COVID-19, SLE and psychosis, given that both psychosis and SLE have been reported in individuals who had or had not a prior history of these diseases prior to contracting COVID-19. The second and most plausible hypothesis is that the patient would have developed a lupus-related psychosis [9], as a severe manifestation of COVID-19 vaccination in an infected individual. In this case, the COVID-19 vaccination coupled with a concomitant infection would have precipitated a strong immune dysregulation and the subsequent onset of a severe form of SLE. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that both COVID-19 infection and vaccine have been shown to trigger SLE [1, 2]. Several explaining mechanisms have been suggested. COVID-19 infection would incite autoimmunity through molecular mimicry between human proteins and the virus [23]. In a similar way, the vaccine produces antibodies against COVID-19 spike protein that can cross-react with antigens from the host and trigger autoimmune diseases in predisposed individuals [24]. A few cases of individuals who developed de novo SLE after receiving Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 mRNA vaccine have been published in the literature (e.g., a 68-year-old Caucasian woman [25], a 42-year-old woman [26], a 24-year-old Israeli male [27], a 27-year-old Puerto Rican woman [28]); however, we could find no reports on the onset of SLE after both vaccine and infection. In our patient, the chronological relationship between COVID-19 infection, vaccination and the first lupus cerebritis manifestations is highly suggestive, albeit with no certainty, of the potential causal link. In addition, the fact that our patient developed SLE symptoms after receiving the second dose of the vaccine suggests that the vaccine-induced immune response was further enhanced by the covid-19 infection, and that the combined effect of both triggers could explain the development of SLE.

People with SLE has proven to have the worse outcomes from COVID-19, and have thus been prioritized to receive the vaccine [24]. The international vaccination against COVID in systemic lupus (VACOLUP) initiative stipulated that, despite the risk of flares, COVID-19 immunization was rather well accepted in patients with SLE [24]. Therefore, we emphasize that our report should not discourage against vaccination, albeit vigilance should be raised among susceptible population about the possible emergence of SLE after mRNA vaccination. Therefore, we suggest that precautionary measures should be taken to decrease the risk of SLE onset or exacerbation after COVID-19 vaccination, including a routine COVID-19 testing before vaccination in individuals with specific predisposition (e.g., a family history of either psychosis or autoimmune diseases).

Given its wide array of clinical manifestations, the diagnosis of SLE may be particularly challenging, especially when lupus cerebritis is the initial presenting feature. Primary psychosis manifestations of SLE may mislead or delay the diagnosis and thus delay appropriate management with poor outcomes and significant impact on mortality. Antipsychotic medication needs to be prescribed in severe psychosis along with required treatment for SLE. Our patient showed substantial improvement of symptoms after joint treatment with antipsychotics and anti-SLE drugs. Similarly, the case report by Khalid et al. [18] showed favorable evolution after treatment with oral olanzapine (5 mg per day) to manage the lupus cerebritis flare-up following COVID-19 infection. It is highly recommended that patients presenting with psychosis features subsequent to covid-19 infection/ vaccination undergo close monitoring and immunological screening to promptly rule out an induced autoimmune disorder.

Conclusion

We report an unusual case of new-onset acute psychosis as a manifestation of lupus cerebritis after concomitant COVID-19 infection and vaccination in a previously healthy young female. In light of the temporal link, we suggest the combined effect of both COVID-19 infection and mRNA vaccine could explain the development of SLE in our patient. In light of the reported case, we highly recommend a routine COVID-19 testing before vaccination in individuals with specific predisposition. However, the present conclusions need to be considered with cautious, and additional data and research is still needed before any firm conclusions about a causal link between COVID-19 mRNA vaccines and autoimmunity can be drawn.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available due to restrictions from the ethics committee but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hu B, Huang S, Yin L. The cytokine storm and COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2021;93(1):250–6.

Olivieri B, Betterle C, Zanoni G. Vaccinations and autoimmune diseases. Vaccines. 2021;9(8):815.

Ramos-Casals M. Viruses and lupus: the viral hypothesis. Lupus. 2008;17(3):163–5.

Zamani B, Moeini Taba S-M, Shayestehpour M. Systemic lupus erythematosus manifestation following COVID-19: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2021;15(1):1–4.

Hajmusa M, Akbar RA. Systemic lupus erythematosus manifestation following COVID-19 infection: a coincidental or causal relation. Yemen J Med 2022:46–8.

Bonometti R, Sacchi M, Stobbione P, Lauritano E, Tamiazzo S, Marchegiani A, Novara E, Molinaro E, Benedetti I, Massone L. The first case of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) triggered by COVID-19 infection. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(18):9695–7.

Assar S, Pournazari M, Soufivand P, Mohamadzadeh D. Systemic lupus erythematosus after coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) infection: case-based review. Egypt Rheumatologist. 2022;44(2):145–9.

Misra DP, Agarwal V, Gasparyan AY, Zimba O. Rheumatologists’ perspective on coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) and potential therapeutic targets. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(7):2055–62.

Hanly JG, Li Q, Su L, Urowitz MB, Gordon C, Bae SC, Romero-Diaz J, Sanchez‐Guerrero J, Bernatsky S, Clarke AE. Psychosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: results from an international inception cohort study. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2019;71(2):281–9.

Chaudhary AMD, Musavi NB, Saboor S, Javed S, Khan S, Naveed S. Psychosis during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of case reports and case series. J Psychiatr Res 2022.

Keshavan MS, Kaneko Y. Secondary psychoses: an update. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):4–15.

American Psychiatric, Association A, Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Volume 10. Washington, DC: American psychiatric association; 2013.

Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, Brinks R, Mosca M, Ramsey-Goldman R, Smolen JS, Wofsy D, Boumpas DT, Kamen DL, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(9):1400–12.

Theetha Kariyanna P, Sabih A, Sutarjono B, Shah K, Vargas Peláez A, Lewis J, Yu R, Grewal ES, Jayarangaiah A, Das S, et al. A systematic review of COVID-19 and Pericarditis. Cureus. 2022;14(8):e27948.

Nannoni S, de Groot R, Bell S, Markus HS. Stroke in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Stroke. 2021;16(2):137–49.

Dein E, Douglas H, Petri M, Law G, Timlin H. Pericarditis in Lupus. Cureus. 2019;11(3):e4166.

Nikolopoulos D, Fanouriakis A, Boumpas DT. Cerebrovascular events in systemic Lupus Erythematosus: diagnosis and management. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2019;30(1):7–15.

Khalid MZ, Rogers S, Fatima A, Dawe M, Singh R. A flare of systemic lupus erythematosus disease after COVID-19 infection: a case of lupus cerebritis. Cureus 2021, 13(7).

Meier AL, Bodmer NS, Wirth C, Bachmann LM, Ribi C, Pröbstel AK, Waeber D, Jelcic I, Steiner UC. Neuro-psychiatric manifestations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review and results from the swiss lupus cohort study. Lupus. 2021;30(10):1565–76.

Wang M, Wang Z, Zhang S, Wu Y, Zhang L, Zhao J, Wang Q, Tian X, Li M, Zeng X. Progress in the pathogenesis and treatment of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Med. 2022;11(17):4955.

Sarwar S, Mohamed AS, Rogers S, Sarmast ST, Kataria S, Mohamed KH, Khalid MZ, Saeeduddin MO, Shiza ST, Ahmad S. Neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus: a 2021 update on diagnosis, management, and current challenges. Cureus 2021, 13(9).

Tariku M, Hajure M. Available evidence and ongoing hypothesis on corona virus (COVID-19) and psychosis: is corona virus and psychosis related? A narrative review. Psychol Res Behav Manage. 2020;13:701.

Dotan A, Muller S, Kanduc D, David P, Halpert G, Shoenfeld Y. The SARS-CoV-2 as an instrumental trigger of autoimmunity. Autoimmun rev. 2021;20(4):102792.

Khatri G, Shaikh S, Rai A, Cheema HA, Essar MY. Systematic lupus erythematous patients following COVID-19 vaccination: its flares up and precautions. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2022;80:104282.

Lemoine C, Padilla C, Krampe N, Doerfler S, Morgenlander A, Thiel B, Aggarwal R. Systemic lupus erythematous after Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine: a case report. Clin Rheumatol. 2022;41(5):1597–601.

Molina-Rios S, Rojas-Martinez R, Estévez-Ramirez GM, Medina YF. Systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome after COVID-19 vaccination. A case report. Mod Rheumatol Case Rep 2022.

Raviv Y, Betesh-Abay B, Valdman-Grinshpoun Y, Boehm-Cohen L, Kassirer M, Sagy I. First Presentation of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in a 24-Year-Old Male following mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine. Case Reports in Rheumatology 2022, 2022.

Báez-Negrón L, Vilá LM. New-onset systemic lupus erythematosus after mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Case Reports in Rheumatology 2022, 2022.

Ramachandran L, Dontaraju VS, Troyer J, Sahota J. New onset systemic lupus erythematosus after COVID-19 infection: a case report. AME Case Reports 2022, 6.

Hali F, Jabri H, Chiheb S, Hafiani Y, Nsiri A. A concomitant diagnosis of COVID-19 infection and systemic lupus erythematosus complicated by a macrophage activation syndrome: a new case report. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60(8):1030.

Gracia-Ramos AE, Saavedra-Salinas M. Can the SARS-CoV-2 infection trigger systemic lupus erythematosus? A case-based review. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41(4):799–809.

Mantovani Cardoso E, Hundal J, Feterman D, Magaldi J. Concomitant new diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus and COVID-19 with possible antiphospholipid syndrome. Just a coincidence? A case report and review of intertwining pathophysiology. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39:2811–5.

Slimani Y, Abbassi R, El Fatoiki FZ, Barrou L, Chiheb S. Systemic lupus erythematosus and varicella-like rash following COVID‐19 in a previously healthy patient. J Med Virol. 2021;93(2):1184–7.

Liu V, Messenger NB. New-onset cutaneous lupus erythematosus after the COVID-19 vaccine. Dermatol Online J 2021, 27(11).

Patil S, Patil A. Systemic lupus erythematosus after COVID-19 vaccination: a case report. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(10):3103–4.

Gamonal SBL, Marques NCV, Pereira HMB, Gamonal ACC. New-onset systemic lupus erythematosus after ChAdOX1 nCoV‐19 and alopecia areata after BNT162b2 vaccination against SARS‐CoV‐2. Dermatol Ther 2022.

Kaur I, Zafar S, Capitle E, Khianey R. COVID-19 vaccination as a potential trigger for new-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Cureus 2022, 14(2).

Molina-Rios S, Rojas-Martinez R, Estévez-Ramirez GM, Medina YF. Systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome after COVID-19 vaccination. A case report. Mod Rheumatol Case Rep. 2023;7(1):43–6.

Zavala-Miranda MF, González-Ibarra SG, Pérez-Arias AA, Uribe-Uribe NO, Mejia-Vilet JM. New-onset systemic lupus erythematosus beginning as class V lupus nephritis after COVID-19 vaccination. Kidney Int. 2021;100(6):1340–1.

Hidaka D, Ogasawara R, Sugimura S, Fujii F, Kojima K, Nagai J, Ebata K, Okada K, Kobayashi N, Ogasawara M. New-onset Evans syndrome associated with systemic lupus erythematosus after BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination. Int J Hematol 2022:1–4.

Nune A, Iyengar KP, Ish P, Varupula B, Musat CA, Sapkota HR. The emergence of new-onset SLE following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. 2021;114(10):739–40.

Kim HJ, Jung M, Lim BJ, Han SH. New-onset class III lupus nephritis with multi-organ involvement after COVID-19 vaccination. Kidney Int. 2022;101(4):826–8.

Sogbe M, Blanco-Di Matteo A, Di Frisco IM, Bastidas JF, Salterain N, Gavira JJ. Systemic lupus erythematosus myocarditis after COVID-19 vaccination. Reumatología Clínica. 2023;19(2):114–6.

Sakai M, Takao K, Mizuno M, Ando H, Kawashima Y, Kato T, Kubota S, Hirose T, Hirota T, Horikawa Y. Two cases of systemic lupus erythematosus after administration of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccine. Mod Rheumatol Case Rep 2023:rxad008.

Beynon J, Alsharkawy M, Sammut L, Ledingham J. NEW-ONSET SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS FOLLOWING COVID-19 VACCINATION: A REPORT OF TWO CASES. Rheumatol (United Kingdom) 2022:i131–2.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FFR and FG drafted the manuscript; SH and MC reviewed the paper for intellectual content; all authors reviewed the final manuscript and gave their consent.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

A written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the use of the clinical data and results from clinical examinations for research. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for the use and publication of the clinical data and results from clinical examinations for research.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Fekih-Romdhane, F., Ghrissi, F., Hallit, S. et al. New-onset acute psychosis as a manifestation of lupus cerebritis following concomitant COVID-19 infection and vaccination: a rare case report. BMC Psychiatry 23, 419 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04924-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04924-4