Abstract

Background

Vaccination is an important public health strategy; however, many neurological adverse effects are associated with COVID-19 vaccination, being encephalitis a rare manifestation.

Case presentation

We present the case of a 33-year-old woman who received the first dose of the BBIBP-CorV vaccine against COVID-19 on April 4 and the second dose on April 28, 2021. Three days after receiving the second dose, she experienced a subacute episode of headache, fever, insomnia, and transient episodes of environment disconnection. We obtained negative results for infectious, systemic, and oncological causes. Brain magnetic resonance imaging showed lesions in the bilateral caudate nucleus and nonspecific demyelinating lesions at the supratentorial and infratentorial compartments. The results of the neuronal autoantibodies panel were negative. She had an adequate response to immunoglobulin and methylprednisolone; however, she experienced an early clinical relapse and received a new cycle of immunosuppressive treatment followed by a satisfactory clinical evolution.

Conclusions

We report the first case of severe encephalitis associated with BBIBP-CorV (Sinopharm) vaccination in Latin America. The patient had atypical imaging patterns, with early clinical relapse and a favorable response to corticosteroid therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

As of January 27, 2022, more than 356 million cases and 5.6 million deaths have been reported worldwide due to COVID-19 [1]. The lack of a specific treatment regimen has led to the development of different types of vaccines, some of which have already been approved by many countries such as the United States and the European Union [2]. On July 6, 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported approximately 61.5 per 100 people worldwide are already vaccinated with two doses, generating a significant reduction in severe cases and deaths [1].

BBIBP-CorV (developed by Sinopharm) is an inactivated virus vaccine whose phase 3 clinical trials were carried out in several countries, including Peru [3]. The WHO has supported the efficacy of this vaccine and has been distributed worldwide for immunization. Neurological adverse effects, such as encephalitis, myelitis, and Guillain Barré syndrome have been reported with the different vaccines against COVID-19. Therefore, the prevalence of postvaccination adverse effects is under exploration as we write [4, 5].

The mechanism by which vaccines cause these complications has not been established yet; however, compromised humoral immunity, molecular mimicry, and aberrant immune reactions are possible hypotheses. Previous case reports have described severe postvaccination adverse effects after different COVID-19 vaccines [4,5,6,7]. However, few studies describe these adverse effects after the application of the BBIBP-CorV vaccine. Therefore, we present the case of a patient with clinical manifestations of autoimmune encephalitis after the administration of a second dose of the BBIBP-CorV vaccine (Sinopharm).

Case presentation

We present the case of a self-sufficient 33-year-old woman, with no relevant history. She was diagnosed with COVID-19 using an antigenic test for SARS-CoV-2 in July 2020 and presented with mild symptoms without requiring oxygen or hospitalization. She received the first dose of the BBIBP-CorV COVID-19 vaccine on April 4, 2021, and the second dose on April 28 same year.

She was admitted to the neurology service of a referral hospital in Peru after three weeks of illness characterized by severe headache, the sensation of thermal rise, conciliation insomnia, and transitory episodes of environment disconnection that began 3 days after receiving the second vaccine dose.

The neurologist evaluated the patient and found that she was confused and unresponsive to simple commands with a tendency to mutism, bilateral pyramidal tract lesions, generalized hyperreflexia, and no signs of meningeal irritation.

Suspecting acute encephalitis, we performed a brain computed tomography (CT) without contrast, finding no pathological results. In addition, we examined the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) without suggestive findings of infection. We equally prescribed blood count and basic biochemical serum tests that showed no abnormalities. Due to the suspicion of autoimmune encephalitis, we started a five-day dual immunosuppressive treatment scheme with methylprednisolone (1 g daily). We added immunoglobulin (0.4 g/kg daily) on the second day of admission after carrying out serum and CSF tests.

On the eighth day after admission, we performed brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast that revealed nonspecific demyelinating lesions at the periventricular region, right cerebellum, internal capsule, and bilateral subcortical areas (Fig. 1). Due to the disconnection with the environment episodes, we performed a prolonged electroencephalogram examination that did not record associated epileptiform activity.

The serum and CSF studies were negative for inflammatory disease (oligoclonal bands in serum and CSF), systemic autoimmune pathologies (C3, C4, antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, extractable nuclear antigens, rheumatoid factor), neoplastic causes (Pap smear in CSF, flow cytometry and immunofixation in CSF, tumor markers: CEA, CA 125, CA 15–3, AFP, CYFRA 21.1) and associated infectious causes (serological test for syphilis, test for toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex, viral load of cytomegalovirus, John Cunningham virus in serum and CSF, herpes virus in CSF, HIV, Epstein-Barr virus in serum and CSF, human T-lymphotropic virus type I and II, adenosine deaminase and Koch bacillus in CSF). The cervical, thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic CT scans with contrast excluded the presence of neoplasms.

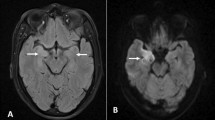

During the first three weeks of hospitalization, the patient improved clinically (consciousness, speech emission, and coherency); however, after three weeks of hospitalization and awaiting the autoimmune encephalitis panel results, the patient’s condition worsened, with sustained confusion, apathy-abulic, and gait apraxia. For this reason, we requested another brain MRI that demonstrated new well-defined hyperintense lesions at the bilateral caudate nucleus (Fig. 2).

We started a new cycle of methylprednisolone 1 g daily for five days, with subsequent maintenance therapy of 1 mg/kg of prednisone. Post 1 week of starting the new cycle, the patient improved significantly. The autoimmune encephalitis panel results of the cerebrospinal fluid (NMDA, CASPR2, AMPA 1, AMPA 2, GABA, and LGI 1) and anti-MOG were negative. We then concluded the diagnosis of seronegative autoimmune encephalitis associated with the COVID-19 vaccine. The patient was discharged after a 2-months hospital stay and received outpatient follow-up with oral prednisone without reporting clinical relapses.

Discussion and conclusion

The annual incidence of encephalitis is estimated at 5–8 cases per 100,000 people, with autoimmune encephalitis being the third most common cause of encephalitis, after infectious and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) [8]. Within the spectrum of autoimmune encephalitis, the subtype with antibodies against the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) is the most frequent and represents approximately 1% of all admissions of young adults in intensive care units. However, some cases present without detectable antibodies, are considered seronegative, and require a more specific diagnostic approach [8, 9].

The increase in COVID-19 vaccination coverage has allowed for the monitoring of possible adverse effects, most being neurologically mild. However, cases of encephalitis and ADEM have been reported in some countries with viral vectors [10], mRNA [11], and inactivated virus [12] vaccines. Postvaccination encephalitis is associated with antineural antibodies or seronegative in pathophysiological association with an immune-mediated response triggered by the vaccination process in a person [10,11,12,13]. Most of the cases reported were female, developed symptoms after receiving the first dose, and present a median of 9 days postvaccination [13].

The inactive whole virus vaccine prepared by inoculating Verda Reno cells with the WIV04 and HB02 SARS-CoV-2 strain, produced by the Sinopharm laboratory, has been widely used in Asia and Latin America [14]. Our present case is the first case reported in this region to our knowledge.

The clinical presentation of a previous case in Jordan of autoimmune encephalitis due to this vaccine manifested clinically as generalized tonic-clonic seizures with corroborated epileptiform activity on the electroencephalogram [15]. This differs from our case, which was severe, and manifested clinically as an altered state of consciousness without epileptiform activity, postulating a diverse manifestation in these patients without a single pattern.

Cases of nonspecific periventricular lesions have been reported with CoronaVac (manufactured by Sinovac laboratory) vaccination, similar to BBIBP-CorV (Sinopharm). This explains a similar radiological behavior associated with these vaccines [16]. In our patient, multiple nonspecific periventricular demyelinating lesions were observed in the bilateral caudate nucleus, a finding not reported to date in autoimmune encephalitis associated with COVID-19 vaccination [15, 17,18,19,20,21,22]. Like other cases of immune-mediated encephalitis, she was placed on immunosuppressive treatment with corticosteroids, which usually leads to a favorable response in most cases [8, 10,11,12,13]. However, our patient presented an early clinical relapse, prompting a new cycle with corticosteroid therapy, leading to a favorable response and without relapse during outpatient follow-up.

In conclusion, we report the first case of severe encephalitis associated with BBIBP-CorV (Sinopharm) vaccination in Latin America, with atypical imaging findings, an early clinical relapse following treatment, and a favorable response to corticosteroid therapy as an immunosuppressive supplementary treatment.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this case report are included in it published version.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CEA:

-

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- CA 125:

-

Cancer antigen 125

- CA 15–3:

-

Cancer antigen 15–3

- AFP:

-

Alpha-fetoprotein

- CYFRA 21.1:

-

Cytokeratin 19 fragment antigen

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- CASPR2:

-

Contactin-associated protein-like 2

- AMPA 1:

-

Alpha-Amino-3-Hydroxy-5-Methyl-4-Isoxazole Propionic Acid 1

- AMPA 2:

-

Alpha-Amino-3-Hydroxy-5-Methyl-4-Isoxazole Propionic Acid 2

- GABA:

-

Gamma-aminobutyric acid

- LGI 1:

-

Leucine rich glioma inactivated 1 protein

- Anti-MOG:

-

Anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- ADEM:

-

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

- NMDAR:

-

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor

References

Organization WH. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard [Internet]. Available at: https://covid19whoint/table 2022.

Yap C, Ali A, Prabhakar A, Prabhakar A, Pal A, Lim YY, et al. Comprehensive literature review on COVID-19 vaccines and role of SARS-CoV-2 variants in the pandemic. Therapeutic Advances in Vaccines and Immunotherapy. 2021;9:25151355211059791.

Xia S, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Yang Y, Gao GF, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, BBIBP-CorV: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):39–51.

Kaulen LD, Doubrovinskaia S, Mooshage C, Jordan B, Purrucker J, Haubner C, et al. Neurological autoimmune diseases following vaccinations against SARS-CoV-2: a case series. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29(2):555–63.

Garg RK, Paliwal VK. Spectrum of neurological complications following COVID-19 vaccination. Neurol Sci. 2021;1-38.

Sahraian MA, Ghadiri F, Azimi A, Moghadasi AN. Adverse events reported by Iranian patients with multiple sclerosis after the first dose of Sinopharm BBIBP-CorV. Vaccine. 2021;39(43):6347–50.

Saeed BQ, Al-Shahrabi R, Alhaj SS, Alkokhardi ZM, Adrees AO. Side effects and perceptions following Sinopharm COVID-19 vaccination. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;111:219–26.

Dalmau J, Graus F. Antibody-mediated encephalitis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(9):840–51.

Graus F, Escudero D, Oleaga L, Bruna J, Villarejo-Galende A, Ballabriga J, et al. Syndrome and outcome of antibody-negative limbic encephalitis. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(8):1011–6.

Permezel F, Borojevic B, Lau S, de Boer HH. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) following recent Oxford/AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccination. Forensic Science: Medicine and Pathology; 2021. p. 1–6.

Shimizu M, Ogaki K, Nakamura R, Kado E, Nakajima S, Kurita N, et al. An 88-year-old woman with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following messenger ribonucleic acid-based COVID-19 vaccination. eNeurologicalSci. 2021;25:100381.

Cao L, Ren L. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccination: a case report. Acta Neurol Belg. 2021;1-3.

Ismail II, Salama S. A systematic review of cases of CNS demyelination following COVID-19 vaccination. J Neuroimmunol. 2022;362:577765.

Baraniuk C. What do we know about China’s covid-19 vaccines? BMJ. 2021;373:n912.

Abu-Riash A, Tareef AB, Aldwairy A. Could Sinopharm COVID-19 vaccine cause autoimmune encephalitis? A Case Report. MAR Neurology. 2021;3(5):1-5.

Ozgen Kenangil G, Ari BC, Guler C, Demir MK. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis-like presentation after an inactivated coronavirus vaccine. Acta Neurol Belg. 2021;121(4):1089–91.

Torrealba-Acosta G, Martin JC, Huttenbach Y, Garcia CR, Sohail MR, Agarwal SK, et al. Acute encephalitis, myoclonus and sweet syndrome after mRNA-1273 vaccine. BMJ Case Reports CP. 2021;14(7):e243173.

Flannery P, Yang I, Keyvani M, Sakoulas G. Acute psychosis due to anti-Nmethyl D-aspartate receptor encephalitis following COVID-19 vaccination: a case report. Front Neurol. 2021;12:764197.

Takata J, Durkin SM, Wong S, Zandi MS, Swanton JK, Corrah TW. A case report of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine–associated encephalitis. BMC Neurol. 2021;21(1):1–5.

Fan HT, Lin YY, Chiang WF, Lin CY, Chen MH, Wu KA, et al. COVID-19 vaccine-induced encephalitis and status epilepticus. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. 2022;115(2):91–3.

Shin HR, Kim BK, Lee ST, Kim A. Autoimmune encephalitis as an adverse event of COVID-19 vaccination. Journal of Clinical Neurology (Seoul, Korea). 2022;18(1):114.

Al-Mashdali AF, Ata YM, Sadik N. Post-COVID-19 vaccine acute hyperactive encephalopathy with dramatic response to methylprednisolone: a case report. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2021;69:102803.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MAV, MMAC, EC, DC, AA, EB, and MFA treated the patient. MAV, MMAC, EC, DC, AA, EB, MFA, and DUP interpreted the neuroradiologic imaging and laboratory markers. All authors participated in designing, writing, critical reviewing, and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

We obtained the patient written informed consent to participate in this study. Also, the patient gave us permission for the publication of images, or other personal or clinical details included in this case report.

Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Vences, M.A., Araujo-Chumacero, M.M., Cardenas, E. et al. Autoimmune encephalitis after BBIBP-CorV (Sinopharm) COVID-19 vaccination: a case report. BMC Neurol 22, 427 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-022-02949-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-022-02949-y