Abstract

Background

The use of oral (PO) antibiotics following a course of certain intravenous (IV) antibiotics is proposed in order to avoid the complications of IV medications and to decrease the cost. However, the efficacy and safety of sequential IV/PO antibiotics is unclear and requires further study.

Methods

The databases, including PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane Library, were searched. Studies comparing outcomes in patients with perforated appendicitis receiving sequential IV/PO and PO antibiotics therapy were screened. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) and the Jadad score were used to evaluate the quality of the cohort and the randomized controlled portions of the trial, respectively. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 value. A fixed or random-effect model was applied according to the I2 value.

Results

Five controlled studies including a total of 580 patients were evaluated. The pooled estimates revealed that sequential IV/PO antibiotic therapy did not increase the risk of complications, with a risk ratio (RR) of 0.97 (95% CI 0.51–1.83, P = 0.93) for postoperative abscess, 1.04 (95% CI 0.25–4.36, P = 0.96) for wound infection and 0.62 (95% CI 0.33–1.16, P = 0.13) for readmission.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that sequential IV/PO antibiotic therapy is noninferior to IV antibiotic therapy regarding postoperative abscess, wound infection and readmission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Appendicitis is the most common abdominal condition requiring emergent surgery in the pediatric age group [1, 2]. Perforated appendicitis accounts for 15–50% of cases of pediatric appendicitis [3, 4]. Appendectomy following a course of antibiotic treatment is generally accepted in the practice of managing perforated appendicitis in children. Nevertheless, there is not a consensus regarding the optimal antibiotic regimen in pediatric patients with perforated appendicitis, including the specific antibiotic regimen, treatment duration, and administration route [5, 6]. Peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) and intravenous (IV) lines are widely used to administer antibiotics because of the long duration of treatment. Even though a PICC line is more convenient than an IV line, as it can be used after patients are discharged from the hospital, a PICC line still has many of the same disadvantages as an IV line, including activity restrictions, painful insertion, risk of infections and mechanical complications [7,8,9].

It is suggested here that the use of oral (PO) antibiotics following a course of IV antibiotics could be administered to avoid the complications that may be associated with long-term use of a PICC line for antibiotics. However, it would be concerning if the use of PO antibiotics following an IV antibiotic course increases the risk of complications of perforated appendicitis and results in treatment failure. Although some trials have been conducted to evaluate this problem, those studies failed to draw a robust conclusion due to the small sample sizes of each trail, which ideally would have had a much larger sample size in each treatment arm [5]. We conducted this meta-analysis to answer the question of whether sequential IV/PO antibiotic therapy is equivalent to IV antibiotic therapy.

Methods

Study selection

Controlled studies that compared the outcomes of treating with IV antibiotics to the outcomes of treating with a transition to oral antibiotics after appendectomy in patients with perforated appendicitis were included. Perforated appendicitis was defined as a discernable hole in the vermiform appendix or evidence of a perforation such as an extraluminal fecalith in the abdomen. Furthermore, eligible studies were required to record at least one of the following outcomes: postoperative abscess, wound infection or readmission. The eligible studies were limited to those that had been published in English.

Search strategy

Two researchers (C.W. and Y.J.) independently searched the EMBASE, PubMed and Cochrane Library databases to identify potential studies. The key search terms were ‘intravenous,’ ‘oral,’ ‘antibiotics,’ and ‘appendicitis,’ and these words were combined with the Boolean operator AND. Each of the two investigators independently inspected titles and abstracts and scrutinized full-text manuscripts of the selected studies to identify eligible literature that met the inclusion criteria. Reference lists of eligible literature were reviewed to screen any other potential studies. Based on previous studies, a perforation was defined as a hole in the appendix or a fecalith in the abdomen [10].

Data extraction and quality assessment

This study was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). Postoperative abscess was defined as the primary outcome. Wound infection and readmission were defined as the secondary outcomes. Two authors (C.W. and Y.J.) independently extracted and recorded the following data from the included studies: the name of the first author, the year of publication, the number of cases and controls, the study design, the primary outcomes, and the secondary outcomes. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to evaluate the quality of the included cohort studies [11]. The total score ranged from 0 to 9, and a study with a score of more than 5 was regarded as a “high quality” study. The Jadad score, ranging from 0 to 5, was used to assess the quality of included randomized controlled trials [12]. Studies with a score of at least 3 were considered to be “high quality” studies.

Statistical analysis and exploration of heterogeneity

The meta-analysis was conducted by using the Reviewer Manager 5.3 from the Cochrane Collaboration. The Mantel–Haenszel method was used in the meta-analysis. The risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was employed for the pooled results of all outcomes. The potential for publication bias was assessed using funnel plots. Heterogeneity among studies was evaluated by the I2 method, with a higher I2 value indicating a higher heterogeneity. If the I2 value was less than 50%, a fixed-effects model of analysis was applied; otherwise, a random-effects model was applied.

Results

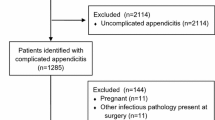

Figure 1 shows the results of the search and the selection of articles. The low stringency initial screen identified 183 articles through an online search and by reviewing reference lists of relevant publications. Six articles were evaluated for eligibility after further scrutinizing the titles and abstracts. Five studies were included in the final analyses [13,14,15,16,17]. Among the five articles, three were randomized controlled studies and two were retrospective observational studies. Table 1 showed the characteristics and scores of these studies. A total of 580 patients were assigned to the IV group (n = 306) or the IV/PO group (n = 274). The detailed case numbers of each outcome in the five articles were summarized in Table 2. No obvious publication bias was detected in any of the analyses.

Postoperative abscess

Four studies investigated the occurrence of postoperative abscess in pediatric patients with perforated appendicitis [13,14,15, 17]. The occurrence rate of postoperative abscess was 8.2% (17, n = 208) in the IV group and 9.9% (15, n = 151) in the IV/PO group. There was no discernible heterogeneity among the four studies (I2 = 0%). The pooled RR was 0.97 (95% CI 0.51–1.83, P = 0.93). The results showed that there was no significant difference in the occurrence rates of postoperative abscess between the two groups (Fig. 2).

Wound infection

Three studies reported wound infections [14, 15, 17]. In total, wound infection developed in 4 of 156 patients in the IV group and 3 of 101 patients in the IV/PO group. No heterogeneity was identified among these studies (I2 = 0%). Our meta-analysis revealed that there was no statistically significant discrepancy between the two groups (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.25–4.36; P = 0.96) (Fig. 3).

Readmission

Readmission was reported in two studies [14, 16]. The I2 method detected no significant heterogeneity with I2 = 0%. There was no statistically significant discrepancy between the two groups regarding readmission rates, with a pooled RR of 0.62 (95% CI 0.33–1.16; P = 0.13) (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Perforated appendicitis is a common abdominal emergency in children. Antibiotic therapy combined with appendectomy is used worldwide to treat perforated appendicitis. In 1994, Lund et al. [18] proposed a “gold standard” of antibiotic therapy for perforated appendicitis. The treatment regimen included 10 days of intravenous antibiotics. However, the IV route results in higher costs, longer length of hospital stay and less safety than the PO route. Thus, the conversion to PO after a course of IV antibiotics was proposed as an alternate to IV-only treatment. Several studies, including randomized controlled studies and observational studies, were conducted to examine this option [13,14,15,16,17, 19,20,21]. Recent studies provide evidence that PO antibiotic treatment was at least as effective as continuing IV antibiotic therapy. In a prospective study including 80 children with perforated appendicitis, the investigators provided satisfactory results that after appendectomy patients can be safely discharged home with a 7-day course of PO antibiotics when enteral intake is tolerated, regardless of the presence of fever or leukocytosis [22]. Although the outcomes showed that the conversion to PO after a course of IV antibiotics seemed to be feasible, a robust conclusion could not be drawn due to the small sample sizes in these studies.

Postoperative abscess is a main complication of perforated appendicitis and developed in approximately 12% of the patients with perforated appendicitis [23]. Postoperative antibiotic therapy can decrease the risk of abscess [24], and the optimal administration route is usually thought to be IV. In this meta-analysis, the result indicates that the IV/PO route is as effective as the IV route in terms of preventing an abscess. Moreover, it has been reported that PO antibiotics treating already-formed abscesses achieved equivalent outcomes as IV antibiotics [21]. Thus, conversion to PO may be initiated when the patient tolerates an oral diet.

Wound infection is also a common complication of perforated appendicitis, with a prevalence of approximately 17% [23]. Previously, some investigators suggested that wounds should be left open in the presence of perforated appendicitis to avoid an increased likelihood of wound infection and longer hospital stay and cost [25, 26]. A growing number of studies indicated that primary wound closure after appendectomy would be safe even in cases of perforated or gangrenous appendicitis [27,28,29]. In addition, wound infections may also be reduced by using antibiotic therapy. Our study shows that the use of IV/PO antibiotics is noninferior to IV antibiotics with regard to wound infection. In the past, intravenous injection of antibiotics was widely used to treat infectious disease due to a lack of appropriate oral antibiotics. With the development of medical therapy, more broad-spectrum oral antibiotics have been created. Thus, more studies should be conducted to investigate whether PO antibiotics could be used to treat reflux cholangitis or other severe infectious diseases that require long courses of antibiotics.

Readmission is mainly attributed to infection, wound complications and small bowel obstruction. In this study, we found that IV/PO antibiotic therapy did not increase the risk of readmission compared with IV antibiotic therapy. The use of IV-only actually increased the risk of readmission compared with PO in patients with complicated appendicitis, and it lead to more repeat visits due to complications associated with the IV or PICC line [20]. Although the introduction of PICC provided a therapeutic advance, as it allowed patients to be discharge home to complete their IV antibiotic therapy once recovered from their operation, the use of PICC is not without risk. Well-known adverse events, including painful insertion, activity restrictions, and risk of mechanical and infectious complications, were commonly documented in patients using PICC lines [8]. In patients receiving PO antibiotics, the PICC complications can be avoided entirely. Only a small number of patients experience a failure of PO antibiotics, and this is primarily due to protracted vomiting. Our study suggested that enough bioavailability and blood concentration of antibiotics could be achieved to treat severe infectious disease by the PO route when the gastrointestinal function recovered.

Some limitations of this study should be recognized. The included studies are limited, and further studies should be conducted to investigate this issue. The regimens of IV/PO antibiotics and IV antibiotics vary among studies because there is not yet a consensus formed regarding an optimal antibiotics option. The timing for conversion from IV to PO is also different among the selected studies.

Conclusions

This research provides valuable evidence with respect to the efficacy and safety of sequential IV/PO antibiotic therapy in patients with perforated appendicitis. Our study demonstrates that sequential IV/PO antibiotic therapy is equivalent to IV antibiotic therapy regarding postoperative abscess, wound infection and readmission. Further studies should be conducted to confirm this conclusion and the optimal timing for conversion.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- IV:

-

Intravenous

- NOS:

-

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- PICC:

-

Peripherally inserted central catheter

- PO:

-

Oral

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

References

Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:910–25.

Pearl RH, Hale DA, Molloy M, Schutt DC, Jaques DP. Pediatric appendectomy. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:173–8.

Curran TJ, Muenchow SK. The treatment of complicated appendicitis in children using peritoneal drainage: results from a public hospital. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:204–8.

Goldin AB, Sawin RS, Garrison MM, Zerr DM, Christakis DA. Aminoglycoside-based triple-antibiotic therapy versus monotherapy for children with ruptured appendicitis. Pediatrics. 2007;119:905–11.

Nadler EP, Gaines BA. The surgical infection society guidelines on antimicrobial therapy for children with appendicitis. Surg Infect. 2008;9:75–83.

Newman K, Ponsky T, Kittle K, Dyk L, Throop C, Gieseker K, et al. Appendicitis 2000: variability in practice, outcomes, and resource utilization at thirty pediatric hospitals. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:372–9.

Barrier A, Williams DJ, Connelly M, Creech CB. Frequency of peripherally inserted central catheter complications in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:519–21.

Jumani K, Advani S, Reich NG, Gosey L, Milstone AM. Risk factors for peripherally inserted central venous catheter complications in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:429–35.

Sulkowski JP, Asti L, Cooper JN, Kenney BD, Raval MV, Rangel SJ, et al. Morbidity of peripherally inserted central catheters in pediatric complicated appendicitis. J Surg Res. 2014;190:235–41.

St Peter SD, Sharp SW, Holcomb GW 3rd, Ostlie DJ. An evidence-based definition for perforated appendicitis derived from a prospective randomized trial. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:2242–5.

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12.

Adibe OO, Barnaby K, Dobies J, Comerford M, Drill A, Walker N, et al. Postoperative antibiotic therapy for children with perforated appendicitis: long course of intravenous antibiotics versus early conversion to an oral regimen. Am J Surg. 2008;195:141–3.

Arnold MR, Wormer BA, Kao AM, Klima DA, Colavita PD, Cosper GH, et al. Home intravenous versus oral antibiotics following appendectomy for perforated appendicitis in children: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Surg Int. 2018;34:1257–68.

Fraser JD, Aguayo P, Leys CM, Keckler SJ, Newland JG, Sharp SW, et al. A complete course of intravenous antibiotics vs a combination of intravenous and oral antibiotics for perforated appendicitis in children: a prospective, randomized trial. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1198–202.

Loux TJ, Falk GA, Burnweit CA, Ramos C, Knight C, Malvezzi L. Early transition to oral antibiotics for treatment of perforated appendicitis in pediatric patients: confirmation of the safety and efficacy of a growing national trend. J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51:903–7.

Rice HE, Brown RL, Gollin G, Caty MG, Gilbert J, Skinner MA, et al. Results of a pilot trial comparing prolonged intravenous antibiotics with sequential intravenous/oral antibiotics for children with perforated appendicitis. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1391–5.

Lund DP, Murphy EU. Management of perforated appendicitis in children: a decade of aggressive treatment. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:1130–3.

Acker SN, Hurst AL, Bensard DD, Schubert A, Dewberry L, Gonzales D, et al. Pediatric appendicitis and need for antibiotics at time of discharge: does route of administration matter? J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51:1170–3.

Rangel SJ, Anderson BR, Srivastava R, Shah SS, Ishimine P, Srinivasan M, et al. Intravenous versus Oral antibiotics for the prevention of treatment failure in children with complicated appendicitis: has the abandonment of peripherally inserted catheters been justified? Ann Surg. 2017;266:361–8.

Sujka JA, Weaver KL, Sobrino JA, Poola A, Gonzalez KW, St Peter SD. Efficacy of oral antibiotics in children with post-operative abscess from perforated appendicitis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2019;35:329–33.

Gollin G, Abarbanell A, Moores D. Oral antibiotics in the management of perforated appendicitis in children. Am Surg. 2002;68:1072–4.

Hartwich JE, Carter RF, Wolfe L, Goretsky M, Heath K, St Peter SD, et al. The effects of irrigation on outcomes in cases of perforated appendicitis in children. J Surg Res. 2013;180:222–5.

Dickinson CM, Coppersmith NA, Luks FI. Early Predictors of Abscess Development after Perforated Pediatric Appendicitis. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2017;18:886–9.

Chiang RA, Chen SL, Tsai YC, Bair MJ. Comparison of primary wound closure versus open wound management in perforated appendicitis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2006;105:791–5.

Henry MC, Moss RL. Primary versus delayed wound closure in complicated appendicitis: an international systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21:625–30.

Chatwiriyacharoen W. Surgical wound infection post surgery in perforated appendicitis in children. J Med Assoc Thail. 2002;85:572–6.

McGreal GT, Joy A, Manning B, Kelly JL, O'Donnell JA, Kirwan WW, et al. Antiseptic wick: does it reduce the incidence of wound infection following appendectomy? World J Surg. 2002;26:631–4.

Mehrabi Bahar M, Jangjoo A, Amouzeshi A, Kavianifar K. Wound infection incidence in patients with simple and gangrenous or perforated appendicitis. Arch Iran Med. 2010;13:13–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants Nos. 81400862 and 81401606), the Key Project in the Science & Technology Program of Sichuan Province (Grant No. 2019YFS0322), the Science Foundation for The Excellent Youth Scholars of Sichuan University (Grant No. 2015SU04A15), and the 1·3·5 project for disciplines of excellence–Clinical Research Incubation Project of West China Hospital of Sichuan University (Grant No. 2019HXFH056). These foundations provided financial support for data collection and publication costs. The funding bodies had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YJ contributed to the design of the study. CW and YJ performed the literature search, reviewed the data and analyzed the data. YJ, CW and YL interpreted the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C., Li, Y. & Ji, Y. Intravenous versus intravenous/oral antibiotics for perforated appendicitis in pediatric patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr 19, 407 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1799-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1799-6