Abstract

Background

Older adults are at high risk of developing delirium in the emergency department (ED); however, it is under-recognized in routine clinical care. Lack of detection and treatment is associated with poor outcomes, such as mortality. Performance measures (PMs) are needed to identify variations in quality care to help guide improvement strategies. The purpose of this study is to gain consensus on a set of quality statements and PMs that can be used to evaluate delirium care quality for older ED patients.

Methods

A 3-round modified e-Delphi study was conducted with ED clinical experts. In each round, participants rated quality statements according to the concepts of importance and actionability, then their associated PMs according to the concept of necessity (1–9 Likert scales), with the ability to comment on each. Consensus and stability were evaluated using a priori criteria using descriptive statistics. Qualitative data was examined to identify themes within and across quality statements and PMs, which went through a participant validation exercise in the final round.

Results

Twenty-two experts participated, 95.5% were from west or central Canada. From 10 quality statements and 24 PMs, consensus was achieved for six quality statements and 22 PMs. Qualitative data supported justification for including three quality statements and one PM that achieved consensus slightly below a priori criteria. Three overarching themes emerged from the qualitative data related to quality statement actionability. Nine quality statements, nine structure PMs, and 14 process PMs are included in the final set, addressing four areas of delirium care: screening, diagnosis, risk reduction and management.

Conclusion

Results provide a set of quality statements and PMs that are important, actionable, and necessary to a diverse group of clinical experts. To our knowledge, this is the first known study to develop a de novo set of guideline-based quality statements and PMs to evaluate the quality of delirium care older adults receive in the ED setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Delirium is a serious condition of acute neurological dysfunction occurring in up to 38% of older emergency department (ED) patients [1,2,3]. Although older adults (i.e., people 65 years of age and older) are at high risk of developing delirium in the ED [4,5,6,7], it is missed in 57% to 85% of these patients [2, 8]. Lack of detection and treatment in the ED is associated with poorer outcomes such as increased length of hospital stay and mortality [7, 9,10,11,12,13,14]. Improving delirium care for older ED patients is hindered by underlying knowledge gaps and lack of practice standards for care in this setting [15]. Mechanisms to evaluate ED practice performance are needed to identify gaps and variations in quality care to focus delirium care improvement strategies where they are most needed.

Performance measures (PMs) are tools to quantify measurable aspects of practice performance [16, 17]. These are usually classified as structures (i.e., conditions under which care is provided) or processes (i.e., diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation, and prevention of health conditions) of care as defined in Donabedian’s seminal framework of healthcare quality and measurement [18]. The extent that PMs are observed in practice provides an indication of the quality of the care provided and the likelihood of attaining optimal patient outcomes (i.e., changes in an individual or population attributable to healthcare) [17, 19, 20].

Numerous researchers and organizations assert that clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) are an essential first step in developing quality statements (i.e., concise statements defining best practice in a specific context), which in turn can be transformed into operationalizable metrics as PMs [16, 17, 19, 21,22,23]. Therefore, quality statements can be used to guide best practice and are an important antecedent to developing PMs that are necessary to evaluate the quality of care provided [16, 17, 19, 21]. In the past decade, work has been done to increase the methodological rigor of developing guideline-based PMs [16, 17, 24, 25]. Nothacker et al. (2016), as part of the Guidelines International Network (G-I-N), developed standards for generating guideline-based PMs [16], which have been used to inform our work.

Based on the results of an umbrella review of current delirium CPGs [26], we developed a preliminary set of quality statements and PMs grouped into four categories of delirium care: screening, diagnosis, risk reduction, and management. Criteria for quality statement and PM development from the umbrella review were: (1) agreement across two or more CPGs that the action or intervention be done, and (2) that the action or intervention was identified as a priority for implementation by at least one CPG group. No high-quality ED-specific delirium CPGs were found during our umbrella review, therefore we included CPGs from across the care continuum. However, the ED setting was included in the evidence base for many of the recommendations included in our synthesis [26]. To supplement the umbrella review and support the development of the PMs, structured searches of the Scopus and PubMed bibliographic databases were conducted for any recently published research relevant to delirium care for older adults in the ED specifically. Seven evidence syntheses [1,2,3, 27,28,29,30] and three multi-centre observational studies [8, 14, 31] were included as additional evidence to support the PMs.

Results from the umbrella review, supported by additional recent ED-specfic research, provided an evidence-based foundation for the creation of a set of quality statements (N = 10), and subsquent PMs (N = 24), for delirium care in the ED. Methods and criteria for conducting the transformation from CPG recommendation synthesis—to quality statement—to PM were incorporated into developing this preliminary set [16, 19, 25, 32]. For example, ensuring that each developed PM addresses an aspect of structure or process that is linked by evidence to improved outcomes, uses specific and unambiguous (i.e., concise) language, and is designed to be measurable [16, 19, 25, 32]. The greater number of PMs versus quality statements reflects the potential need to develop a structure and process PM from the same quality statement, or to develop more than one process PM to address the same quality statement to ensure the PMs are concise and are measurable. The next step in establishing a set of PMs for use was to conduct a formal consenus process with a diverse panel of experts to finalize a set of PMs from the transformed recommendations [16]. As the transformed recommendations were from CPGs for the entire care continuum, this next step was vitally important to ensure the final set of PMs are relevant to the ED, as well as to increase their credibility and acceptability in this setting [16, 23,24,25, 32,33,34].

The purpose of this study was to gain consensus on a set of guideline-based quality statements and PMs to guide and evaluate delirium care quality for older ED patients. To achieve this, we conducted a modified e-Delphi study to reach consensus among key clinical experts on a set of ED quality statements and PMs.

Methods

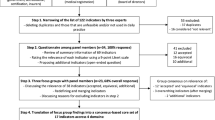

This 3-round modified e-Delphi study was conducted between April and July 2023. The methods of this study have been previously detailed in our open-access protocol [35], and are briefly described here. The design was informed by the Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) [36], and other recommended criteria [33, 37]. This study received approval from the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (ID HS25728 [H2022:340]). Informed consent was received from all participants before completing any questionnaires. The consent process and each round was conducted electronically and anonymously using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) secure online platform for building and managing online surveys [38] through the University of Manitoba licensing agreement [39]. The study flow and objectives for each round are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Study steering group

We convened a steering group with members consisting of co-authors (with methodological and clinical expertise), two patient/family representatives, and two further clinical experts (one ED physician and one registered nurse with experience as an ED front-line provider and clinical decision-maker). The steering group met at key stages to provide oversight on protocol design; to give feedback on Delphi questionnaire development, structure, and clarity; and to help identify potential Delphi participants. Including patient/family representatives in the steering group helped support the patient-centeredness of the quality statements and PMs by ensuring they contain aspects of care important to patients and families and suggesting alternative terminology that better reflects patient views. Members of the steering group who are not co-authors did not have access to raw study data and were not able to influence the study process. Feedback and changes suggested by the steering group were agreed between the study co-authors before implementation.

Expert panel selection

An expert in this study is defined as one with clinical knowledge in the care of older adults in the ED.

Inclusion criteria:

-

Able to read and write in English;

-

Willing to participate, and;

-

Meet one or more of the following criteria: (1) clinical experience in a relevant field to the ED care of older adults for five or more years post-basic graduation, (2) postgraduate qualifications or credentials relevant to the management of delirium in older adults, or (3) recognition by peers as an expert in the area (e.g., member of a relevant organization or network).

Exclusion criteria:

-

Insufficient clinical knowledge and experience in a relevant area (e.g., system-level decision-maker, patient, or < 5 years post-basic clinical experience), or;

-

Unable to commit to be available for the entire process.

Recruitment

The initial recruitment period lasted 4 weeks to identify Canadian experts through existing professional networks and associations (e.g., Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians [CAEP] and National Emergency Nurses Association [NENA]); email invitations and advertisements; social media calls (LinkedIn, Twitter, and/or Facebook); and snowballing from other experts. Our minimum a priori sample size (N = 17) was not achieved after 4 weeks therefore, recruitment was extended for an additional 4 weeks and expanded to include eligible international clinical experts.

Survey design and development

The primary questionnaire in our study consisted of closed-ended questions with the opportunity to provide comments for each quality statement and related PMs to justify decisions and suggest edits to increase clarity. Each round was also accompanied by an introduction section to refamiliarize panelists to the study, state the intentions of the round, and provide definitions for key concepts.

Questionnaire development was informed by PM assessment instruments (i.e., AIRE [40] and QUALIFY [41]), criteria used by organizations that develop and implement PMs (i.e., the National Quality Forum [42] and NICE [19]), as well as syntheses of these sources [16, 32, 43]. Panelists were asked to judge each quality statement according to its importance and actionability; then, were asked to judge each related PM according to its necessity (see Table 1). The quality statements and PMs were scored using these criteria, on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 9. Delphi participants were advised to think of each 9-point scale being made up of three parts (i.e., tertiles), where 1 to 3 could be used to record low ratings (i.e., not at all important, actionable and/or necessary), 4 to 6 record average ratings (i.e., somewhat important, actionable and/or necessary), and 7 to 9 record high ratings (i.e., very important, actionable and/or necessary). A response option of ‘I do not know’ was also provided to capture uncertainty. A question was included in the first two rounds on the Delphi to gain consensus on a reasonable timeframe to complete delirium screening upon arrival to the ED. This timeframe was incorporated in the associated quality statement and PM in the final round of the Delphi. A rationale for each quality statement and its PMs (including a summary of the evidence) was provided in each round to enable participants to make informed judgements.

Prior to implementing the Delphi survey, the questionnaire was piloted with clinical expert steering group members. The purpose of this process was to ensure that the PMs are clearly and precisely worded with unambiguous language, and that each set of PMs reflect the quality statement they are meant to measure. For example, as quality statements are defined as “concise statements defining best practice in a specific context” it was agreed to call the quality statements ‘best practices’ in the Delphi questionnaire to decrease the number of new concepts introduced to participants and to increase comprehensibility and readability of the survey. A copy of the Round 1 questionnaire that was approved for implementation by the steering group, which includes all preliminary ‘best practices’ (i.e., quality statements) and PMs, is provided in Supplemental File 1.

Procedure

In our modified e-Delphi process, a minimum of three rounds were planned a priori to allow participants to have feedback, revise previous responses, then stabilize responses [44, 45].

Defining consensus and stability

We used the RAND criteria for agreement to define consensus [46], which aligns with PM development frameworks [32, 47]. Consensus was defined as 80% of ratings within the 3-point tertile of the overall median. The lower tertile (1–3) represents scores that are ‘not at all’, the middle tertile (4–6) represents scores that are ‘somewhat’, and the upper tertile (7–9) represents scores that are ‘very’ important, actionable, and/or necessary. To be included in the final set, quality statements and PMs needed to reach consensus in the upper tertile (i.e., overall panel median of 7 to 9, with 80% of ratings within the 3-point tertile of the overall median). Those that achieved consensus just below a priori thresholds were considered during qualitative data analysis and interpretation to determine justification for potential inclusion [37].

A measurement of stability was used as a stopping criterion for the Delphi process. This was defined as the consistency of responses between successive rounds (i.e., no meaningful change) [44, 45, 48]. Meaningful change was defined as a median change between tertiles and a greater than 15% change in the percentage of participants whose scores changed tertiles [45, 48].

Stopping and PM removal criteria

For the overall study, the criterion to stop the Delphi process was defined as no meaningful change in scores between the current and preceding round on at least 75% of quality statements and PMs assessed. Additionally, criteria for PM removal were considered after the second round. To be removed from the process, a PM’s scores must have shown no meaningful change from the previous round, and there must have been consensus that the PM is not necessary (i.e., overall panel median of 1 to 3, with 80% of ratings in the lower tertile).

Delphi rounds

In Round 1, along with the questionnaire containing the preliminary set of quality statements and PMs, participants also completed a participant demographics form. In Round 2, a personalized questionnaire was sent to each participant with: quantitative group results (i.e., median, minimum, and maximum ratings) presented numerically and graphically, qualitative feedback (i.e., summary of participants’ comments), and the participant’s own response to illustrate their position in relation to the group. In Round 3, a new personalized questionnaire was sent to each participant with the revised: quantitative group results presented numerically and graphically, qualitative feedback, and the participant’s own response to illustrate their position in relation to the group. Member checking of themes that emerged from feedback in Rounds 1 and 2 was also completed.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequency distributions) were calculated to determine if consensus, stability, PM removal and stopping criteria were met, as well as to present quantitative feedback to participants (median, minimum and maximum values) in rounds two and three. If a participant rated a question as ‘I do not know’ the value was counted as missing and the denominator was adjusted for that question to reflect the number of valid responses. Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel™ for Mac.

Inductive content analysis was used to code and summarize participants’ comments to be fed back to the group in rounds two and three, as well as to provide context during data interpretation and to support justification for including quality statements and PMs slightly below a priori quantitative thresholds in the final set [44, 49, 50]. Following a period of data familiarization, data were coded and counted iteratively to identify themes within each set of, as well as across all, quality statements and PMs. To be classified as a theme to be included in the comment summary for each quality statement and set of PMs, the code needed to be described by a minimum of two participants. Original wording from one expert that best represented the wording for that theme was used where possible [44, 50]. Across all rounds of the Delphi, overarching themes emerged from the coded data. To explore the trustworthiness of these results, extra questions were included in the final round of the Delphi as a form of participant validation (or member checking) [51].

Results

Delphi panel

Fifty-three experts were identified and contacted by the lead author, of which nine were known to snowball the invitation within their professional networks. Advertising by professional associations (e.g., CAEP, NENA, and iDelirium) through email fan-outs and/or social media reached approximately 8,000 individuals. Twenty-four experts expressed interest and met eligibility requirements. Of those, 22 provided consent and were enrolled into the study.

Over half of panelists were physicians (n = 12, 54.6%), followed by registered nurses (n = 6, 27.3%) (see Table 2). Over two-thirds of panelists’ primary work setting was the ED or urgent care (n = 15, 68.2%), and approximately two-thirds had 10 or more years of clinical experience (n = 14, 63.6%). Self-reported level of experience in older adult care on a 9-point Likert scale ranged from 5 to 9 (median = 7). Almost all panelists were from west or central Canada (n = 21, 95.5%). All panelists were retained in the final round of the Delphi (N = 22, 100%), with one missing response in Round 2.

Quality statement and PM selection

Quantitative results summary

Panelists evaluated 10 quality statements with 24 associated PMs, addressing four areas of delirium care (screening, diagnosis, risk reduction, and management). Criteria to stop the Delphi process were met after Round 3. Results were 98% stable between the second and third round. Quantitative results from all rounds are presented in Supplemental File 2. None of the PMs met removal criteria, therefore, all PMs and quality statements were retained in all three rounds to achieve or strengthen consensus on a final set. The experts reached consensus that six of the 10 quality statements were very important and very actionable (see Table 3). A further three quality statements were established as very important, but no consensus was reached as to their actionability; ratings ranged from 63.6% in the upper tertile for Quality Statement 08 (Multicomponent management) to 72.7% for Quality Statements 04 (Multicomponent risk reduction) and 09 (Cautious use of antipsychotic medications). For these nine quality statements, experts agreed that all associated PMs were very necessary, except for PM 06 (Repeat screening every shift) which fell below the a priori threshold (72.7%).

Quality Statement 06 (Reduce unnecessary within-ED transfers) and its associated PM 14 did not meet criteria to be included in the final set. Although the Quality Statement reached consensus for importance (90.9% in upper tertile) only 27.3% rated it to be very actionable, and 50.0% rated the associated PM to be very necessary.

Qualitative results summary

Three overarching themes emerged from the qualitative responses, all related to the current actionability of the quality statements. The overall themes, organizing concepts for each theme presented to panelists in the final round, and examples of associated quotes (i.e., supporting quotes used to develop themes, as well as opposing theme quotes where applicable) are presented in Table 4. There was high agreement (95.5%) with first theme, ‘System-Level Impacts on the ED’, in which panelists described system-level issues, such as access block and ED crowding, thought to decrease the current actionability of the quality statements although they were perceived to be important. In contrast, panelists explained that the complex nature of bed management and patient flow in the ED made the reduction of within-ED transfers (Quality Statement 06) both non-actionable and unnecessary to evaluate. Instead of focusing on transfers within the ED, there was unanimous agreement with the second theme, ‘Prioritization for Transfer to Care Unit or Home’. Although panelists agreed older adults should be prioritized for transfer out of the ED, they also expressed the importance of improving care within the ED and shared ideas how some of the actionability issues could be addressed with adequate resources. These ideas are represented in the final theme, ‘Additional Healthcare Provider Supports’, which was also endorsed unanimously.

Qualitative results provide justification for including three quality statements that achieved consensus slightly below a priori thresholds (Quality Statements 04, 08, and 09). Many panelists who rated quality statements lower for actionability, rated the associated PMs as very necessary in recognition that the evidence generated from their measurement has the potential to guide improvement efforts (e.g., “This is extremely important and valuable to the care of the patient. For statistical purposes, it would be good to know what proportion of patients are receiving this, but my impression would be that this would be dismal”, “Unlikely to achieve, but it would be nice to have this data to drive change”, and “Data important to guide further change” [Experts rating quality statements lower for actionability and higher for PM necessity]). Lastly, PM 06 (Repeat screening every shift) reached consensus slightly below our a priori inclusion threshold as some participants viewed ongoing delirium screening being out of the scope of ED care (e.g., “…The fact that these poor patients stay hours if not days in an ED screams system problem. The fact that the ED teams will have to do daily screens for these patients should be the real issue” [Expert rating PM 06 in mid tertile]). While other participants thought repeat screening was necessary, as older adults tend to spend a longer time in the ED (e.g., “I wonder if the frequency of every 24 h is not enough to capture and evaluate ED care. Perhaps every nursing shift (so twice a day)…” and “I think delirium screening should be occurring once per shift (every 12 h), given how quickly it can develop in the ED” [Experts rating PM 06 in high tertile]). Due to known long standing issues with increased lengths of stay in EDs across Canada [52], and globally [53, 54], as well as increased incidence of delirium associated with ED lengths of stay over 10 h [3], it was decided to retain this PM for preliminary testing under the recognition that as care improves, attainment increases, and variability decreases over time, de-implementation of some of the PMs, such as PM 06, may be warranted [16].

Final set of quality statements and PMs

The final quality statement and PM set consisted of nine quality statements and 23 PMs, including nine structure PMs and 14 process PMs (see Table 5). Wording for some of the quality statements and PMs were modified after Rounds 1 and 2 based on panelist feedback. For example, multiple panelists viewed conducting delirium screening re-assessment once per nursing shift (instead of daily) was more practical. Two additions were also made based on expert consensus. First, a time benchmark of initial screening to be completed within 4 h of arrival to the ED was added, with 85.7% of panelists agreeing on this as a reasonable timeframe after two rounds. Second, prioritizing transfer to more appropriate care spaces was added as part of multicomponent interventions for risk reduction and management (Quality Statements 04 and 08) based on 100% agreement during the participant validation exercise. This addition is also supported by a recent systematic review and meta-analysis in which Oliveira and colleagues found that the odds of developing delirium increased over two-fold in older adults with ED lengths of stay over 10 h (OR, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.13–4.41) [3].

Discussion

There have been few attempts to establish PMs to evaluate quality of care for older ED patients in relation to delirium. Existing PMs are reported to be of low methodological quality and predominately based on pre-existing metrics [57,58,59,60]. PMs are only as good as the evidence and methods used to develop them [32, 43]. Poorly developed PMs can lead to unintended consequences by providing misleading information to guide decision-making, policy development, and quality improvement efforts [43]. There is general agreement in the ED quality of care literature that there is a need to rigorously develop new evidence-based PMs instead of basing work on pre-existing metrics [53, 57, 61]. In our study we developed a set of delirium quality statements and PMs for the care of older adults in the ED setting by conducting a formal consensus process. To our knowledge, this is the first known research to develop a de novo set of guideline-based metrics on this topic.

A diverse group of clinical experts reached consensus on a set of quality statements that are important, and associated PMs that are necessary to evaluate the quality of delirium care older adults receive in the ED. All quality statements in the final set reached consensus at or slightly below the a priori criterion for actionability, with a large caveat that much of this care would only be actionable with appropriate tools and resources available. There was overwhelming agreement that the current state of healthcare systems, especially in which many EDs are dealing with access block (inpatient boarding), crowding, and staffing constraints decreases the actionability of much of the care in the delirium quality statements, although there is agreement this care is important. Similarly, Eagles and colleagues (2022) found that ED clinicians identified delirium as important but it was not prioritized in the care of older ED patients [62]. Perceived lack of time, competing priorities, and increased demand have been identified as key barriers to delirium assessment and management by Canadian ED clinicians in two recent qualitative studies [62, 63]. These barriers to high-quality care delivery in the ED have only worsened in recent months [64] as the global pandemic has come to an end [65]. System-wide staffing shortages, bed closures, and pent-up demand have exacerbated access block and put increased pressures on EDs across Canada [64, 66, 67], as well as in many other countries such as the United States [68], United Kingdom [69], and Australia [70]. The one participant who disagreed with this theme in our study pointed out that there will always be competing priorities in the ED, and it is critical to make delirium care for older adults a priority or it will always be overlooked.

Despite system-level issues, clinical experts agreed more can be done within the ED to support the actionability of the quality statements and improve quality care. Implementing roles for other providers such as Nurse Practitioners and Geriatric Emergency Management (GEM) nurses were perceived to have great potential benefit in the screening, assessment, and management of delirium in the ED. Previous research has demonstrated that advanced practice nurses have a key role in successfully implementing practice change and improving ED quality care for older adults [71, 72]. Beyond the introduction of additional healthcare providers, tools are also needed to support ED clinicians to provide high-quality care.

The quality statements generated by this study can be used to guide practice change and enhance standardized electronic documentation. For example, they can be used to develop and embed risk reduction and management protocols, as well as embed screening tools into an electronic documentation system. Recent studies have reported improved delirium assessment and diagnosis in the ED with similar initiatives [73,74,75]. Further, embedding such tools and protocols will support reliable data capture, which will facilitate the ability to use the developed PMs to monitor and evaluate patient care. The PMs are necessary to provide baseline data to guide improvement efforts where they are most needed. Metrics such as these have been identified as an important component of quality improvement efforts, not only to provide evidence to governments and administrators, but also to increase frontline-provider awareness, enhance staff education, and increase buy-in [29, 73,74,75]. Prior to implementation, the PMs will undergo preliminary testing to ensure they are feasible to use to evaluate ED quality care [16].

This study has some key limitations. Despite our efforts to recruit broadly across Canada and internationally we encountered difficulties. This, unto itself, may speak to the increased burnout being experienced by ED providers world-wide since the pandemic [76]. Similarly, while we attempted to recruit other types of healthcare professionals (e.g., clinical educators and managers) none of these experts were willing to participate in our study. As most of our panelists were from Canada, this may limit the generalizability of our results. ED researchers can use the final set of quality statements and PMs from this study to repeat a similar consensus-building process with a different group of clinical experts to validate or further contextualize our results for different countries. Further, situational and personal biases can influence differences in how panelist make judgements when using the Delphi method [44]. We attempted to constrain these biases by limiting time between rounds, providing detailed background information and clear definitions for all concepts, providing quantitative and qualitative personalized feedback, as well as clearly defining consensus and stopping criteria.

Conclusion

Our results confirm that high-quality delirium care is an important focus in the ED, although the quality statements and PMs were based on evidence from across the care continuum. This is the first known study to develop a set of guideline-based quality statements and PMs to evaluate the quality of care older adults receive in the ED setting. Results will be used in future research to test the feasibility of using the PMs to evaluate delirium care quality and guide improvement efforts.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- PM:

-

Performance measure

- CPG:

-

Clinical practice guideline

- G-I-N:

-

Guidelines International Network

- CREDES:

-

Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies

- REDCap:

-

Research Electronic Data Capture

- CAEP:

-

Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians

- NENA:

-

National Emergency Nurses Association

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- GEM:

-

Geriatric Emergency Management

References

Chen F, Liu L, Wang Y, Liu Y, Fan L, Chi J. Delirium prevalence in geriatric emergency department patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;59:121–8. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735675722003679. Cited 2022 Sep 6.

Barron EA, Holmes J. Delirium within the emergency care setting, occurrence and detection: a systematic review. Emerg Med J. 2013;30(4):263–8. Available from: http://emj.bmj.com/content/30/4/263. Cited 2022 Mar 26.

Oliveira J E Silva L, Berning MJ, Stanich JA, Gerberi DJ, Murad MH, Han JH, et al. Risk factors for delirium in older adults in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;78(4):549–65.

Cole MG, Ciampi A, Belzile E, Zhong L. Persistent delirium in older hospital patients: a systematic review of frequency and prognosis. Age Ageing. 2009;38(1):19–26.

Hsieh SJ, Madahar P, Hope AA, Zapata J, Gong MN. Clinical deterioration in older adults with delirium during early hospitalisation: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(9):e007496. Available from: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/5/9/e007496.full.pdf+html.

Griffith LE, Gruneir A, Fisher K, Panjwani D, Gandhi S, Sheng L, et al. Patterns of health service use in community living older adults with dementia and comorbid conditions: a population-based retrospective cohort study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):177. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0351-x. Cited 2018 Dec 15.

Kennedy M, Enander RA, Tadiri SP, Wolfe RE, Shapiro NI, Marcantonio ER. Delirium risk prediction, healthcare use and mortality of elderly adults in the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(3):462–9.

Boucher V, Lamontagne ME, Nadeau A, Carmichael PH, Yadav K, Voyer P, et al. Unrecognized incident delirium in older emergency department patients. J Emerg Med. 2019;57(4):535–42. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0736467919304196. Cited 2022 Sep 21.

Cole MG, McCusker J, Bailey R, Bonnycastle M, Fung S, Ciampi A, et al. Partial and no recovery from delirium after hospital discharge predict increased adverse events. Age Ageing. 2017;46(1):90–5.

Bo M, Bonetto M, Bottignole G, Porrino P, Coppo E, Tibaldi M, et al. Postdischarge clinical outcomes in older medical patients with an emergency department stay-associated delirium onset. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(9):e18-19.

Emond M, Boucher V, Carmichael PH, Voyer P, Pelletier M, Gouin E, et al. Incidence of delirium in the Canadian emergency department and its consequences on hospital length of stay: a prospective observational multicentre cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e018190.

Émond M, Grenier D, Morin J, Eagles D, Boucher V, Le Sage N, et al. Emergency department stay associated delirium in older patients. Can Geriatr J. 2017;20(1):10–4. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5383401/. Cited 2020 Apr 28.

Arneson ML, Oliveira J E Silva L, Stanich JA, Jeffery MM, Lindroth HL, Ginsburg AD, et al. Association of delirium with increased short-term mortality among older emergency department patients: a cohort study. Am J Emerg Med. 2023;66:105–10.

Anand A, Cheng M, Ibitoye T, Maclullich AMJ, Vardy ERLC. Positive scores on the 4AT delirium assessment tool at hospital admission are linked to mortality, length of stay and home time: two-centre study of 82,770 emergency admissions. Age Ageing. 2022;51(3):afac051. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afac051. Cited 2022 May 2.

Eagles D. Delirium in older emergency department patients. Can J Emerg Med. 2018;20(6):811–2. Available from: http://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/canadian-journal-of-emergency-medicine/article/delirium-in-older-emergency-department-patients/480D2CC4E413A8E20D097999BD441AF4. Cited 2020 Jan 26.

Nothacker M, Stokes T, Shaw B, Lindsay P, Sipilä R, Follmann M, et al. Reporting standards for guideline-based performance measures. Implement Sci. 2016;11(6). Available from: http://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-015-0369-z. Cited 2019 Jul 6.

Parmelli E, Langendam M, Piggott T, Adolfsson J, Akl EA, Armstrong D, et al. Guideline-based quality assurance: a conceptual framework for the definition of key elements. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):173. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06148-2. Cited 2021 Mar 4.

Donabedian A. An introduction to quality assurance in health care. Bashshur R, editor. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE]. Health and social care directorate quality standards process guide. Manchester: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2020. Available from: www.nice.org.uk. Cited 2021 Jan 21.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America [IOM]. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines [IOM]. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Graham R, Mancher M, Miller Wolman D, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209539/. Cited 2017 Jun 9.

Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318(7182):527.

Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall M. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11(4):358–64. Available from: http://qualitysafetybeta.bmj.com/content/11/4/358. Cited 2016 Oct 28.

Langendam MW, Piggott T, Nothacker M, Agarwal A, Armstrong D, Baldeh T, et al. Approaches of integrating the development of guidelines and quality indicators: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1–11. Available from: http://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-020-05665-w. Cited 2020 Nov 15.

Kötter T, Blozik E, Scherer M. Methods for the guideline-based development of quality indicators–a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):1–22. Available from: http://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748-5908-7-21. Cited 2020 Apr 23.

Filiatreault S, Grimshaw JM, Kreindler SA, Chochinov A, Linton J, Chatterjee R, et al. A critical appraisal and recommendation synthesis of delirium clinical practice guidelines relevant to the care of older adults in the emergency department: an umbrella review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2023;29(6):1039–53. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jep.13883. Cited 2023 Jun 15.

Tieges Z, Maclullich AMJ, Anand A, Brookes C, Cassarino M, O’connor M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the 4AT for delirium detection in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2021;50(3):733–43.

Burton JK, Craig LE, Yong SQ, Siddiqi N, Teale EA, Woodhouse R, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for preventing delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;2021(7). Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85111139573&doi=10.1002%2f14651858.CD013307.pub2&partnerID=40&md5=499c53dcc973d1966c62a986b9f69694.

Carpenter CR, Hammouda N, Linton EA, Doering M, Ohuabunwa UK, Ko KJ, et al. Delirium Prevention, detection, and treatment in emergency medicine settings: a Geriatric Emergency Care Applied Research (GEAR) network scoping review and consensus statement. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(1):19–35. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/acem.14166. Cited 2022 Mar 17.

Lee S, Chen H, Hibino S, Miller D, Healy H, Lee JS, et al. Can we improve delirium prevention and treatment in the emergency department? A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(6):1838–49. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jgs.17740. Cited 2022 Jul 6.

Béland E, Nadeau A, Carmichael PH, Boucher V, Voyer P, Pelletier M, et al. Predictors of delirium in older patients at the emergency department: a prospective multicentre derivation study. CJEM. 2021;23(3):330–6.

Campbell SM, Kontopantelis E, Hannon K, Burke M, Barber A, Lester HE. Framework and indicator testing protocol for developing and piloting quality indicators for the UK quality and outcomes framework. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:85. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3176158/. Cited 2019 Jul 17.

Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLOS One. 2011;6(6):e20476. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0020476. Cited 2018 Oct 25.

Rubin HR, Pronovost P, Diette GB. Methodology matters. From a process of care to a measure: the development and testing of a quality indicator. Int J Qual Health Care. 2001;13(6):489–96.

Filiatreault S, Kreindler S, Grimshaw J, Chochinov A, Doupe M. Protocol for developing a set of performance measures to monitor and evaluate delirium care quality for older adults in the emergency department using a modified e-Delphi process. BMJ Open. 2023;13(8):e074730. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/13/8/e074730. Cited 2023 Aug 22.

Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, Radbruch L, Brearley SG. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med. 2017;31(8):684–706. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216317690685. Cited 2021 Aug 4.

Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, Pencharz PB, Ling SC, Moore AM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(4):401–9. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0895435613005076. Cited 2021 Aug 4.

REDCap. Available from: https://www.project-redcap.org/. Cited 2021 Sep 1.

University of Manitoba - information services and technology - enterprise applications - database services - REDCap consultation. Available from: https://umanitoba.ca/computing/ist/service_catalogue/enterprise_app/database/3210.html. Cited 2021 Sep 1.

de Koning JS, Kallewaard M, Klazinga NS. Prestatie-indicatoren langs de meetlat – het AIRE instrument. TVGW. 2007;85(5):261–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03078683. Cited 2021 Aug 16.

Reiter A, Fischer B, Kötting J, Geraedts M, Jäckel WH, Döbler K. QUALIFY: Ein Instrument zur Bewertung von Qualitätsindikatoren. Zeitschrift für ärztliche Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen - German J Qual Health Care. 2008;101(10):683–8. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1431762107002862. Cited 2021 Aug 16.

National Quality Forum. NQF: measure evaluation criteria. 2023. Available from: https://www.qualityforum.org/Measuring_Performance/Submitting_Standards/Measure_Evaluation_Criteria.aspx. Cited 2023 Oct 7.

Busse R, Klazinga N, Panteli D, Quentin W, editors. Improving healthcare quality in Europe: characteristics, effectiveness and implementation of different strategies. Copenhagen: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2019.

Keeney S, Haason F, McKenna H. The Delphi technique in nursing and health research. 1st ed. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2011. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781444392029. Cited 2021 Jan 20.

von der Gracht HA. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies: review and implications for future quality assurance. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2012;79(8):1525–36. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0040162512001023. Cited 2021 Sep 9.

Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, Burnand B, LaCalle JR, Lazaro P, et al. The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method user’s manual. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation; 2001. Available from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1269.html.

Carinci F, Van Gool K, Mainz J, Veillard J, Pichora EC, Januel JM, et al. Towards actionable international comparisons of health system performance: expert revision of the OECD framework and quality indicators. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015;27(2):137–46.

Dajani JS, Sincoff MZ, Talley WK. Stability and agreement criteria for the termination of Delphi studies. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 1979;13(1):83–90. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0040162579900076. Cited 2021 Oct 17.

Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398–405. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/nhs.12048. Cited 2021 Sep 9.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, Campbell C, Walter F. Member checking: a tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1802–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316654870. Cited 2023 Jul 16.

Kreindler SA, Schull MJ, Rowe BH, Doupe MB, Metge CJ. Despite interventions, emergency flow stagnates in Urban Western Canada. Healthc Policy. 2021;16(4):70–83. Available from: https://www.longwoods.com/product/26498.

Hansen K, Boyle A, Holroyd B, Phillips G, Benger J, Chartier LB, et al. Updated framework on quality and safety in emergency medicine. Emerg Med J. 2020;37(7):437–42. Available from: http://emj.bmj.com/content/37/7/437. Cited 2021 Feb 24.

Badr S, Nyce A, Awan T, Cortes D, Mowdawalla C, Rachoin JS. Measures of emergency department crowding, a systematic review. How to make sense of a long list. Open Access Emerg Med. 2022;14:5–14. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2147/OAEM.S338079. Cited 2023 Jul 30.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [SIGN]. Risk reduction and management of delirium. Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; 2019. Report No.: SIGN publication no. 157. Available from: https://www.sign.ac.uk/our-guidelines/risk-reduction-and-management-of-delirium/. Cited 2019 Aug 29.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE]. Delirium: Diagnosis, prevention and management. London: National Clinical Guideline Centre; 2023. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg103. Cited 2023 Jan 18.

Burkett E, Martin-Khan MG, Gray LC. Quality indicators in the care of older persons in the emergency department: a systematic review of the literature. Australas J Ageing. 2017;36(4):286–98. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.proxy.hil.unb.ca/doi/10.1111/ajag.12451/abstract. Cited 2018 Feb 1.

Schnitker LM, Martin-Khan M, Burkett E, Brand CA, Beattie ERA, Jones RN, et al. Structural quality indicators to support quality of care for older people with cognitive impairment in emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(3):273–84. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/acem.12617. Cited 2018 Oct 22.

Schnitker LM, Martin-Khan M, Burkett E, Beattie ERA, Jones RN, Gray LC. Process quality indicators targeting cognitive impairment to support quality of care for older people with cognitive impairment in emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(3):285–98.

Schuster S, Singler K, Lim S, Machner M, Döbler K, Dormann H. Quality indicators for a geriatric emergency care (GeriQ-ED) – an evidence-based delphi consensus approach to improve the care of geriatric patients in the emergency department. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2020;28(1):68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-020-00756-3. Cited 2020 Nov 11.

Schull MJ, Guttmann A, Leaver CA, Vermeulen M, Hatcher CM, Rowe BH, et al. Prioritizing performance measurement for emergency department care: consensus on evidence based quality of care indicators. Can J Emerg Med. 2011;13(5):300–9. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/canadian-journal-of-emergency-medicine/article/prioritizing-performance-measurement-for-emergency-department-care-consensus-on-evidencebased-quality-of-care-indicators/0C9DF3CCA4F8AAB29A64FC83F7ECF8D6. Cited 2016 Oct 30.

Eagles D, Cheung WJ, Avlijas T, Yadav K, Ohle R, Taljaard M, et al. Barriers and facilitators to nursing delirium screening in older emergency patients: a qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. Age Ageing. 2022;51(1):afab256. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afab256. Cited 2022 Feb 7.

Schonnop R, Dainty KN, McLeod SL, Melady D, Lee JS. Understanding why delirium is often missed in older emergency department patients: a qualitative descriptive study. Can J Emerg Med. 2022;24(8):820–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-022-00371-4. Cited 2023 Jul 25.

Varner C. Emergency departments are in crisis now and for the foreseeable future. CMAJ. 2023;195(24):E851-2. Available from: https://www.cmaj.ca/content/195/24/E851. Cited 2023 Aug 9.

World Health Organisation. Statement on the fifteenth meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 pandemic. 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic. Cited 2023 Aug 9.

Weeks C. How Canada’s emergency rooms are faring as major staffing shortages persist. The Globe and Mail; 2023. Available from: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-canadian-hospitals-er-rooms-summer/. Cited 2023 Aug 9.

Miller A, Bamaniya P. Why ERs are under intense pressure across Canada — and how to help fix them | CBC News. CBC; 2023. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/canada-er-pressure-health-care-system-solutions-1.6885257. Cited 2023 Jun 24.

Alltucker K. Against backdrop of a mental health care shortage, emergency room doctors are overwhelmed. USA TODAY; 2023. Available from: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2023/06/21/american-hospital-emergency-room-doctors-issue-warning/70341882007/. Cited 2023 Aug 9.

Boyle A. Unprecedented? The NHS crisis in emergency care was entirely predictable. BMJ. 2023;380:46. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/380/bmj.p46. Cited 2023 Aug 9.

Australian College of Emergency Medicine [ACEM]. ACEM - Doctor shortages in emergency departments set to worsen in 2023. 2023. Available from: https://acem.org.au/News/January-2023/Doctor-shortages-in-emergency-departments-set-to-w. Cited 2023 Aug 9.

Leaker H, Fox L, Holroyd-Leduc J. The impact of geriatric emergency management nurses on the care of frail older patients in the emergency department: a systematic review. Can Geriatr J. 2020;23(3):250–6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7458600/. Cited 2023 Aug 9.

Babine RL, Honess C, Wierman HR, Hallen S. The role of clinical nurse specialists in the implementation and sustainability of a practice change. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24(1):39–49. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jonm.12269. Cited 2023 Aug 9.

Vardy E, Collins N, Grover U, Thompson R, Bagnall A, Clarke G, et al. Use of a digital delirium pathway and quality improvement to improve delirium detection in the emergency department and outcomes in an acute hospital. Age Ageing. 2020;49(4):672–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afaa069. Cited 2023 Aug 9.

Ibitoye T, Jackson TA, Davis D, MacLullich AMJ. Trends in delirium coding rates in older hospital inpatients in England and Scotland: full population data comprising 7.7M patients per year show substantial increases between 2012 and 2020. Delirium Communications; 2023. Available from: https://deliriumcommunicationsjournal.com/article/84051-trends-in-delirium-coding-rates-in-older-hospital-inpatients-in-england-and-scotland-full-population-data-comprising-7-7m-patients-per-year-show-subs. Cited 2023 Jul 29.

Pendlebury ST, Lovett NG, Thomson RJ, Smith SC. Impact of a system-wide multicomponent intervention on administrative diagnostic coding for delirium and other cognitive frailty syndromes: observational prospective study. Clin Med. 2020;20(5):454–64. Available from: https://www.rcpjournals.org/content/clinmedicine/20/5/454. Cited 2023 Aug 9.

Alanazy ARM, Alruwaili A. The global prevalence and associated factors of burnout among emergency department healthcare workers and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare. 2023;11(15):2220. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/11/15/2220. Cited 2023 Aug 9.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank and acknowledge Jessica Leigh RN, and Dr. Kerri Onotera (clinical experts), as well as Carli Rossall and one member who has chosen to remain anonymous (patient and family representatives) who agreed to be members of the study steering group. The authors would also like to thank all expert participants who took part in this study.

Funding

SF—The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarships – Doctoral Research Award (CGS-D) (FRN – 175944), and the Canadian Nurses Foundation (CNF) Dr. Ann C. Beckingham award. JMG – Canada Research Chair in Health Knowledge Transfer and Uptake (950–200986) and CIHR Foundation grant (FDN – 143269). SAK – Manitoba Research Chair in Health System Innovation (Research Manitoba).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SF conceived the research idea under the supervision of MBD, SAK, JMG, and AC. The manuscript was first drafted by SF and MBD, additional content and draft reviews were provided by SAK, JMG, and AC. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was designed and conducted according to the principles outlined in the Canadian Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans. This study received approval from the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (ID HS25728 [H2022:340]). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before completing any surveys.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplemental File 1.

Round 1 Delphi Questionnaire as Presented in REDCap.

Additional file 2: Supplemental File 2.

Quality Statement & PM Scores by Delphi Round.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Filiatreault, S., Kreindler, S.A., Grimshaw, J.M. et al. Developing a set of emergency department performance measures to evaluate delirium care quality for older adults: a modified e-Delphi study. BMC Emerg Med 24, 28 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-024-00947-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-024-00947-6