Abstract

Background

Quality indicators (QIs) are used in many healthcare settings to measure, compare, and improve quality of care. For the efficient development of high-quality QIs, rigorous, approved, and evidence-based development methods are needed. Clinical practice guidelines are a suitable source to derive QIs from, but no gold standard for guideline-based QI development exists. This review aims to identify, describe, and compare methodological approaches to guideline-based QI development.

Methods

We systematically searched medical literature databases (Medline, EMBASE, and CINAHL) and grey literature. Two researchers selected publications reporting methodological approaches to guideline-based QI development. In order to describe and compare methodological approaches used in these publications, we extracted detailed information on common steps of guideline-based QI development (topic selection, guideline selection, extraction of recommendations, QI selection, practice test, and implementation) to predesigned extraction tables.

Results

From 8,697 hits in the database search and several grey literature documents, we selected 48 relevant references. The studies were of heterogeneous type and quality. We found no randomized controlled trial or other studies comparing the ability of different methodological approaches to guideline-based development to generate high-quality QIs. The relevant publications featured a wide variety of methodological approaches to guideline-based QI development, especially regarding guideline selection and extraction of recommendations. Only a few studies reported patient involvement.

Conclusions

Further research is needed to determine which elements of the methodological approaches identified, described, and compared in this review are best suited to constitute a gold standard for guideline-based QI development. For this research, we provide a comprehensive groundwork.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the definition of the Institute of Medicine (1990), quality of care is the "degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge" [1, 2]. Increasingly, quality indicators (QIs) are employed to assess and improve the quality of care in many healthcare settings [1, 3–5]. QIs are measurable items referring to structures, processes, and outcomes of care [6]. They imply a judgment on the quality of care provided. However, the interpretation of such performance assessments can have far-reaching consequences, for instance, in application to pay-for-performance models. Hence, the development of QIs should be based on a systematic approach that ensures transparency and produces high-quality standards [7]. Important attributes of high-quality QIs are their relevance to the selected problem and field of application, their feasibility, and their reliability. They further need to be easily understandable for providers and patients, changeable by behavior, achievable, and measurable with high validity [8, 9]. To ensure content and construct validity, QIs need to be evidence based and should have a strong correlation with the actual quality of care provided, respectively [9, 10]. The reliability of QIs in regard to their level of measurement error can be assessed by an evaluation of the intra- and inter-observer reliability [11].

State-of-the-art methodological approaches to QI development have been described in several studies [12–15], and a large body of literature exists evaluating their strengths and limitations [13, 16, 17]. However, to date, no study of which we are aware exists that systematically compares different methodological approaches to QI development with respect to their ability to generate QIs that improve the quality of the particular healthcare aspects they were designed for.

Developing QIs is an expensive and time-consuming process. They are usually specific to certain healthcare settings and, as a result, cannot always be applied to other settings without an adequate adaption process [17]. A time-efficient and resource-saving approach is either to generate QIs from clinical guidelines already available or to couple the process of guideline development with the formulation of appropriate QIs [18, 19]. Due to the aim of clinical practice guidelines to improve quality-of-care processes in practices and care institutions, guideline-based QIs predominantly relate to process quality. However, no gold standard exists for guideline-based QI development [10, 20, 21].

Blozik et al.[20] recently conducted a survey among members of the Guideline International Network (G-I-N [Guidelines International Network, Perthshire, Scotland]) that shows that even among working groups specializing in guideline and QI development, a wide variety of methodological approaches are used. A gold standard would help to standardize procedures, foster transparency, and improve efficiency of resources used.

This review aims to identify, describe, and compare methodological approaches to guideline-based QI development. By pooling the available knowledge and appraising strengths and limitations, we intend to provide the groundwork necessary for defining a gold standard for the development of QIs from clinical practice guidelines. To achieve this, we addressed the following research questions:

-

1.

Which methodological approaches to guideline-based development of QIs have been described so far?

-

2.

What are the strengths and limitations of the methodological approaches described regarding their ability to generate high-quality QIs?

-

3.

Do methodological approaches to the development correlate with the quality of QIs they produce?

Methods

We carried out a systematic literature search across three electronic databases: MEDLINE (US National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA), the Excerpta Medica database (Embase [Elsevier B.V., New York, NY, USA]; both via OvidSP® [Ovid Technologies, Inc., New York, NY, USA]) to cover articles in medical journals that are not included in MEDLINE, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL [EBSCO Publishing, Ipswich, MA, USA]) to include articles published in the field of nursing and the allied health professions. The query date of all three databases was April 22, 2010. The search included literature from the earliest records available in the databases up to the search date. Duplicates were eliminated both manually and automatically. To identify articles for review, we linked three search columns using the Boolean operator "and": quality indicators, guidelines, and development. We combined several search terms with the Boolean operator "or" in order to operationalize the search terms (the MEDLINE search algorithm can be found in Additional file 1: Table S1 and was slightly adapted for Embase and CINAHL). We drew several search terms from the controlled vocabularies used for subject indexing in MEDLINE (i.e., Medical Subject Headings [MeSH]), Embase (i.e., EMTREE), and CINAHL (i.e., CINAHL Subject Headings). We searched three databases for ongoing studies (Current Controlled Trials [Springer Science & Business Media, New York, NY, USA], HSRProj [Health Services Research Projects in Progress, US National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA], UKCRN-Portfolio [United Kingdom Clinical Research Network, National Institute for Health Research, London, UK] [22]). In addition, we screened the reference lists of all retrieved publications included in the final review. From the relevant literature and the G-I-N database, we derived contact information of institutions and working groups in the field of guideline and QI development. We scanned relevant government and institutional websites in order to obtain web-published documents such as method papers (for details of websites searched, see Additional file 2: Table S2). Finally, we consulted colleagues with a research interest in QI to point out articles not identified during our database, websites, and reference list search.

Two reviewers independently screened all obtained references for eligibility in a three-stage screening process. Discrepancies were solved by consensus. Articles were considered for inclusion if they reported at least one methodological approach to guideline-based QI development and if they were published in English, French, or German. All study and publication types were included.

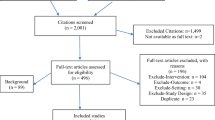

The detailed reporting of the individual development steps (see next paragraph) in publications describing methodological approaches to QI development is indispensable for their reconstruction--be it for the purpose of process evaluation (as we did) or in order to apply methodological approaches to QI development in other settings. We therefore excluded studies at the full-text screening stage that did not describe the extraction of recommendations from clinical guidelines in detail, as this was the process of particular interest to this review. Details of the selection process, including exclusion criteria at the abstract-screening stage, are summarized in Figure 1.

Two researchers independently extracted data from the relevant literature to a predesigned data extraction form (see Additional file 3: Table S3); discrepancies were solved by consensus. In order to describe and to compare methodological approaches to guideline-based QI development, we developed an a priori framework of the QI development process. For this purpose, we identified six steps that most methodological approaches to guideline-based QI development have in common with regard to function and succession but that differ in their design from one methodological approach to another. Through a preliminary search and analysis of a select number of key publications, we identified six development steps: (1) topic selection, (2) guideline selection, (3) extraction of recommendations, (4) QI selection, (5) practice test, and (6) implementation (see Figure 2). The data extraction form was specifically designed to include (a) information about the methodological approach to these six development steps and (b) items necessary to perform a quality assessment of the relevant studies. For steps 1 to 4, we extracted information about how and by whom the specific development step was conducted, such as selection criteria for topics, guidelines, and recommendations, as well as participants. The two development steps specific to guideline-based QI development (compared to QI development from other sources) were investigated in more detail, namely, guideline selection and extraction of recommendations. In addition to the above-mentioned selection criteria, we collected information about the selected guidelines (Was some sort of quality assessment conducted? Were all selected guidelines listed in the publication?), as well as the extracted recommendations (Were they reported at all? If yes, were the source guideline and the underlying level of evidence made transparent?). For an overview of all selected information on guideline selection and extraction of recommendations, see Table 1.

Due to the wide variety of study and publication types and the overlap of the quality assessment and the assessment of methodological approaches, we limited the quality assessment to items covering funding information, the reporting of study and publication type, and the reporting of duration and time frame of the study.

Following data extraction and identification of the methodological approaches to each of the above-listed development steps, we focused on analyzing the similarities and differences among the identified methodological approaches. The results are presented following further elaboration of the six development steps introduced above. We discuss our results in context of the current literature in the Discussion section.

Results

Search findings and literature selection

We identified a total of 8,697 potentially relevant articles, of which 8,468 were excluded based on their titles or abstracts (see Figure 1 for details regarding the screening process). No additional articles were identified through expert consultation. We conducted full-text reviews of the remaining 229 articles and an additional eight articles identified in reference lists and in the grey literature. The final review included 48 articles.

Of the 48 articles in the final review, 10 papers described methodological approaches to guideline-based QI development in general (referred to as "method papers") [1, 7, 23–30], and 32 articles [31–62] addressed the guideline-based QI development for a certain clinical topic (referred to as "topic papers"). An additional six papers [10, 19, 63–66] comprised a detailed description of a method as well as its application for a certain clinical topic (referred to as "method + topic papers"). None of the selected publications was a controlled study comparing one development method to another. All journal articles were published in English; two of the method papers published via institutional websites [25, 26] were written in German.

In not disclosing the funding source and time frame of the study and in not explicitly reporting the study type, many of the publications did not meet our basic quality-assessment criteria (for details, see Table 2).

The identified relevant studies originate from many different institutions and working groups, only a few of which have published more than one relevant study on guideline-based QI development (e.g., the Dutch IQ healthcare [University of Radbound, Nijmegen, The Netherlands]).

Tables 2, 3, and 4 provide an overview of the characteristics of all included publications. Figure 3 provides a comprehensive overview of all methodological approaches identified.

Unless indicated otherwise, numbers of studies referred to in the following paragraphs always relate to all 48 studies of the final review pool.

Topic selection

Criteria for the selection of a clinical topic for QI development were detailed in 33 publications. The most frequently reported criteria were

-

the public health relevance of a topic (mentioned in 18 publications),

-

the existence of a gap between potential and actually achieved quality of healthcare (mentioned in 16 publications).

Other reported criteria were uncertainty about the quality of care provided for a specific healthcare setting (mentioned in six publications), the economical impact of a specific healthcare problem (mentioned in six publications), and the individual impact on the quality of life (mentioned in four publications).

Guideline selection

In 16 studies, QIs were developed from a single guideline, whereas in seven studies more than one guideline was used to derive QIs. Twenty studies detailed other sources, such as existing QI databases, in addition to clinical guidelines.

Only eight of the authors who developed QIs from more than one source provided a transparent description of the respective sources of final QIs.

Criteria for the selection of guidelines from which the QIs were derived were reported in 10 publications. Reported criteria were

-

the methodological quality,

-

the up-to-dateness,

-

the eligibility of a guideline for the selected topic (e.g., with regard to the specific setting).

In 15 publications a critical appraisal of the used guidelines was reported based on the Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation in Europe (AGREE) instrument [67] or similar quality criteria.

Whilst participants in guideline selection are often mentioned, at least indirectly, for instance by being referred to as "the authors", criteria for their selection were reported in only four publications. These selection criteria were

-

member of a guideline development committee,

-

having methodological competence,

-

belonging to a profession involved in the selected healthcare process.

Extraction of recommendations

Nine studies extracted all recommendations from selected guidelines. In 25 studies, recommendations were selected during the extraction process and not all recommendations were extracted as potential QIs. Criteria for this selection were reported in 21 of the 25 studies. Criteria for the preselection at the stage of recommendation extraction mentioned by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) are

-

the size of the impact on patient health (the AHRQ considers the impact great when an issue affects a few patients severely or affects many patients),

-

the relevance to obtaining value for money.

Other criteria for the preselection formulated by Hadorn et al.[39] are

-

the importance to quality of healthcare provided,

-

the feasibility of monitoring.

Other frequently reported criteria were the level of evidence, the grade of recommendation, and measurability.

Levels of evidence and grades of recommendation of the recommendations potential QIs were developed from were reported in 24 studies. Only four studies reported criteria for the selection of persons who extracted potential QIs from guidelines. They were similar to those for persons involved in guideline selection (see above); both tasks were usually carried out by the same group of people.

The AHRQ [24] provides a detailed description of the extraction process, including specifications of participants' necessary skills, as well as criteria for the selection of recommendations to be extracted.

Four requirements for persons involved in the extraction of potential QIs from guidelines postulated by the AHRQ are

-

clinician and nonclinician management skills,

-

clinical expertise,

-

technical expertise in performance measurement,

-

healthcare information management expertise.

Another prerequisite for a valid extraction process mentioned in several of the relevant studies requires that the extraction be performed by at least two researchers independently [25, 37–39].

QI selection

In 35 studies, a consensus method was used to augment the evidence from literature with expert and layperson opinion by letting a panel rate and select a set of final QIs from a set of potential QIs. In 15 of these 35 publications this method was described as the "modified RAND/UCLA method," named after the RAND/UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) appropriateness method [68].

Whereas only a few studies named the individual members of the panels, criteria for their selection (e.g., clinical expertise, methodological expertise, membership in a specialist society) were reported in 31 of 35 studies. Only 25 of 35 studies provided rating criteria for the panel process. Among the frequently named criteria were the usefulness of QIs for improving patient outcomes, their relevance, and the feasibility of monitoring.

Participation of patients in the development process was reported in six studies. In all of these studies, patients participated in the panels. No study reported patient participation during guideline selection and the extraction of recommendations.

Practice test

Only 19 studies reported the conduct of a QI practice test. In two studies, the practice test was conducted after the development process was completed. In 21 studies, a practice test was not mentioned at all.

Implementation

An implementation strategy for guideline-based QIs was reported in 26 studies. Among the reported activities were the instruction of key persons ("early adopters") as multipliers, the participation of end users in the development process, the publication of developed QIs by medical associations, supplying the appropriate software, and the adaptation of "global" QIs to more specific settings. Financial incentives and certification were also used to support implementation.

Discussion

Topic selection

Authors tended to describe the process of topic selection in insufficient detail. Mostly, selection criteria merely reflected the aims of the application of QIs in general: to measure and improve quality in areas of healthcare where the actual quality of care is either suboptimal or unknown.

Guideline selection

The selected literature describes two different approaches to guideline selection. The first approach identified in the reviewed literature is to develop QIs based on one or only a few preselected guidelines, often with the aim of supporting or evaluating guideline implementation. In certain contexts, such as specific settings in small healthcare systems, only one guideline may be available for QI development. In these cases, guideline-selection processes are of no or only minor relevance, and the number of recommendations to be translated into potential QIs is proportionately low.

The second approach is to select a clinical topic and, subsequently, to obtain suitable, topic-specific guidelines as a basis for the development of QIs from guideline recommendations. In this case, expert opinion and existing QI sets are sometimes used as alternative sources for QIs. In comparison to the first approach, this approach provides a broader basis for the subsequent development of QIs, bears the potential to produce a balanced set of QIs, carries a reduced risk of selection bias, and increases content validity.

Many studies do not describe their guideline-selection criteria in sufficient detail and lack critical appraisal of their selected guidelines, both of which may compromise content validity and hence the quality of resulting QI sets. We argue that high-quality QIs can only be derived from high-quality guidelines. To ensure QIs originate from a sound foundation, development committees should (a) conduct a systematic search for relevant guidelines in national and international guideline databases as well as conventional literature databases and (b) conduct a critical appraisal of the methodological quality of selected guidelines (e.g., by using the AGREE instrument) [67].

As is common practice in other areas of research such as guideline development, the documentation of selection criteria for participating persons as well as the disclosure of their names and potential conflicts of interest could greatly add transparency to the whole development process and, as a result, increase the content validity of QIs.

Extraction of recommendations

The main focus of this review is the extraction of guideline recommendations. This step is both crucial and unique to guideline-based QI development, whereas the other steps could also be applied to the development of QIs from other sources such as primary literature or existing QI sets. We only included studies that provided a detailed description of the recommendation-extraction process. As a result, we excluded a large number of otherwise eligible studies (see Additional file 4: Table 4 for a list of studies excluded for this reason).

The reviewed literature describes two different approaches to the extraction of guideline recommendations. The first approach is to initially extract all recommendations and to then select QIs using a systematic consensus process. The second approach is to select a limited number of recommendations during the extraction process. We believe the difference between both approaches is of crucial importance to the quality of ensuing QI sets. Predominantly, only a small number of persons conduct the extraction process. Often, those participants were not selected following transparent selection criteria. The extraction of potential QIs itself through this small group of participants usually does not follow any documented selection criteria, either. As a result, the final QI set may suffer from selection bias.

Subsequent systematic consensus processes to rate and select the extracted potential QIs are usually conducted by larger panels. In comparison to the small group of persons conducting the selection of potential QIs, panel participants are commonly selected to build a balanced panel of different professionals participating in the process of healthcare the QIs are developed for. In addition, the use of predesigned forms containing rating and selection criteria during these systematic consensus processes substantially reduces the risk of selection bias (see "QI selection").

Another important aspect of the extraction process is the translation of the guideline text into recommendations manageable as potential QIs. It can be difficult to derive appropriate numerators and denominators on the basis of the guideline recommendation wording, which may not be specific enough for this purpose. A whole paragraph of guideline text, for instance, cannot easily be translated into a potential QI without cutting out potentially relevant information. Thus, the translation process is a further potential source of bias.

Hence, both the selection of participants as such and the documentation of selection criteria for participants are of great importance. We identified a large deficit in the existing literature regarding this: Only five studies reported selection criteria for participants.

QI selection

Panel methods are not specific to guideline-based QI development and are frequently used to systematically augment the evidence from guidelines with expert opinion (e.g., the widely used RAND/UCLA appropriateness method [68, 69]). Performed carefully, this reduces the risk of unintentional influence of stakeholders on the results of the development process [70]. Panel methods are an established component of the development process of high-quality guidelines. As our results confirm, they are also widely used in the development of QIs [65]. Many of the reviewed studies showed a lack of transparency regarding the nomination process (e.g., in not providing explicit selection criteria for panel members).

Our results show that patient participation during QI development is extremely uncommon. In principle, the frequently used panel method offers room for the participation of patients or patient representatives. However, to date, no standardized approach to patient participation during QI development exists. To fill this gap, our working group is currently conducting a systematic review of approaches to patient participation during QI development.

Practice test

Practice tests prior to publication and usage of QIs are an essential step in evaluating validity, reliability, feasibility, and other important attributes of QIs (see Background). They are an integral part of any implementation strategy and an essential component of the quality loop [7, 26]. The practice test in a study by Wollersheim et al.[10] showed that between 10% and 20% of the developed QIs were not measurable.

It could be argued that regular evaluations of the usage of QIs suffice. However, given the impact QIs can have from day one of their application (e.g., if used in pay-for-performance models [see Background]) and the fact that QIs are more widely accepted after an advance test, it is desirable that practice tests under "laboratory conditions" become established components of the development process.

Implementation

The importance of implementation strategies is often referred to in the course of critical appraisal of guidelines [42]. As for guideline development, implementation strategies are indispensable for the real-life application of QIs [58]. Our results show that even though a wide variety of implementation strategies are reported, they are not always part of the QI development process. Given the importance of implementation, a thorough discussion and application of implementation strategies should be an integral part of a gold-standard QI development method.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of methodological approaches to guideline-based QI development. This systematic review has been conducted following a rigorous methodological approach [71]. The identification of methodological approaches to each step of guideline-based QI development allows a detailed description and comparison of the development methods published so far. We summarized the available evidence from systematically retrieved literature to provide a comprehensive overview of guideline-based QI development.

A major limitation of this study is that we were not able to provide answers to review questions 2 and 3. The selected studies were very heterogeneous in type, in terms of the quality of reporting and in the methodological approaches to guideline-based QI development presented. Because we could not identify any studies comparing different methodological approaches to guideline-based QI development and no gold standard exists to compare the published methodological approaches to, we were not able to provide an evidence-based judgment on the methodological approaches identified. Hence, we were not able to determine whether any of the methodological approaches (as a whole or as single development steps) is "superior" to the others in its ability to generate high-quality QIs.

However, in describing the methodological approaches used by the different working groups developing QIs, we provide a basis for further research. This research should seek to determine which of these methodological approaches applied to individual steps of the development process are best suited to constitute a development pathway that generates the "best" QIs. In order to achieve this aim in view of limited resources, existing guideline developers network infrastructure (e.g., the G-I-N) should be used to cooperate and formulate a gold standard, as proposed by Blozik et al.[20].

Conclusions

A wide variety of methodological approaches are described in the literature for guideline-based QI development. It remains unclear which method leads to the best QIs, since no randomized controlled or other comparative studies investigating this issue exist.

In presenting a comprehensive methodological overview, we provide a groundwork for further research leading to an evidence-based gold standard for guideline-based QI development.

References

Baker R, Fraser RC: Development of review criteria: linking guidelines and assessment of quality. BMJ. 1995, 311: 370-373. 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.370.

Lohr KN: Medicare: a strategy for quality assurance. 1990, Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press

Brook RH, McGlynn EA, Cleary PD: Quality of health care. Part 2: measuring quality of care. N Eng J Med. 1996, 335: 966-970. 10.1056/NEJM199609263351311.

Donabedian A: Evaluating the quality of medical care (1966). Milbank Q. 2005, 83: 691-729. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00397.x.

Mainz J: Quality indicators: essential for quality improvement. Int J Qual Health Care. 2004, 16: i1-i2. 10.1093/intqhc/mzh036.

McGlynn EA, Asch SM: Developing a clinical performance measure. Am J Prev Med. 1998, 14: 14-21. 10.1016/S0749-3797(97)00032-9.

Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall M: Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002, 11: 358-364. 10.1136/qhc.11.4.358.

Sens B, Fischer B, Bastek A, Eckard J, Kaczmarek D, Paschen U, Pietsch B, Rath S, Ruprecht T, Thomeczek C: Begriffe und Konzepte des Qualitätsmanagements. GMS Med Inform Biom Epidemiol. 2007, 3: Doc05-

McGlynn EA: Selecting common measures of quality and system performance. Medical Care. 2003, 41: I-39-I-47.

Wollersheim H, Hermens R, Hulscher M, Braspenning J, Ouwens M, Schouten J, Marres H, Dijkstra R, Grol R: Clinical indicators: development and applications. Neth J Med. 2007, 65: 15-22.

Scinto JD, Galusha DH, Krumholz HM, Meehan TP: The case for comprehensive quality indicator reliability assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001, 54: 1103-1111. 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00381-X.

Brook RH, McGlynn EA, Shekelle PG: Defining and measuring quality of care: a perspective from US researchers. Int J Qual Health Care. 2000, 12: 281-295. 10.1093/intqhc/12.4.281.

Hearnshaw HM, Harker RM, Cheater FM, Baker RH, Grimshaw GM: Expert consensus on the desirable characteristics of review criteria for improvement of health care quality. Qual Health Care. 2001, 10: 173-178. 10.1136/qhc.0100173.

Mainz J: Defining and classifying clinical indicators for quality improvement. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003, 15: 523-530. 10.1093/intqhc/mzg081.

Mainz J: Developing evidence-based clinical indicators: a state of the art methods primer. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003, 15: i5-i11. 10.1093/intqhc/mzg084.

Campbell SM, Shield T, Rogers A, Gask L: How do stakeholder groups vary in a Delphi technique about primary mental health care and what factors influence their ratings?. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004, 13: 428-434. 10.1136/qshc.2003.007815.

Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, McGlynn EA, Campbell SM, Brook RH, Roland MO: Can health care quality indicators be transferred between countries?. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010, 12: 8-12.

Frijling BD, Spies TH, Lobo CM, Hulscher MEJL, Van D, Braspenning JCC, Prins A, Van Der Wouden JC, Grol RPTM: Blood pressure control in treated hypertensive patients: clinical performance of general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 2001, 51: 9-14.

Hutchinson A, McIntosh A, Anderson JL, Gilbert C, Field R: Developing primary care review criteria from evidence-based guidelines: coronary heart disease as a model. Br J Gen Pract. 2003, 53: 690-696.

Blozik E, Nothacker M, Bunk T, Szecsenyi J, Ollenschläger G, Scherer M: Simultaneous Development of Guidelines and Quality Indicators--How Do Guideline Groups Act? A Worldwide Survey. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance. 2010,

Kötter T, Schaefer F, Blozik E, Scherer M: Developing quality indicators: background, methods and problems. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundh wesen (ZEFQ). 2011, 105: 7-12. 10.1016/j.zefq.2010.11.002.

Light K: How to find research before publication. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2009, 14: 62-64. 10.1258/jhsrp.2008.008152.

AHCPR: Designing and implementing guidelines-based performance measures. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Qual Lett Healthc Lead. 1995, 7: 21-23.

AHRQ: Using clinical practice guidelines to evaluate the quality of care--Volume 2: Methods. 1995, Rockville: US Dept. of Health and Human Sciences

AQUA-Institut: Allgemeine Methoden im Rahmen der sektorenübergreifenden Qualitätssicherung im Gesundheitswesen nach §137a SGB V. 2010, Version 2.0

ÄZQ (Ärztliches Zentrum für Qualität in der Medizin): Qualitätsindikatoren--Manual für Autoren. 2009, Neukirchen: Make a book

Bergman DA: Evidence-based guidelines and critical pathways for quality improvement. Pediatrics. 1999, 103: 225-232.

Califf RM, Peterson ED, Gibbons RJ, Garson A, Brindis RG, Beller GA, Smith SC, American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association: Integrating quality into the cycle of therapeutic development. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002, 40: 1895-1901. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02537-8.

Graham WJ: Criterion-based clinical audit in obstetrics: bridging the quality gap?. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009, 23: 375-388. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2009.01.017.

Spertus JA, Eagle KA, Krumholz HM, Mitchell KR, Normand SL: American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association methodology for the selection and creation of performance measures for quantifying the quality of cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2005, 111: 1703-1712. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157096.95223.D7.

Bonow RO, Bennett S, Casey DE, Ganiats TG, Hlatky MA, Konstam MA, Lambrew CT, Normand SL, Pina IL, Radford MJ: ACC/AHA clinical performance measures for adults with chronic heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures (Writing Committee to Develop Heart Failure Clinical Performance Measures) endorsed by the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005, 46: 1144-1178. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.012.

Burge FI, Bower K, Putnam W, Cox JL: Quality indicators for cardiovascular primary care. Can J Cardiol. 2007, 23: 383-388. 10.1016/S0828-282X(07)70772-9.

Campbell SM, Roland MO, Shekelle PG, Cantrill JA, Buetow SA, Cragg DK: Development of review criteria for assessing the quality of management of stable angina, adult asthma, and non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus in general practice. Qual Health Care. 1999, 8: 6-15. 10.1136/qshc.8.1.6.

Desch CE, McNiff KK, Schneider EC, Schrag D, McClure J, Lepisto E, Donaldson MS, Kahn KL, Weeks JC, Ko CY: American Society of Clinical Oncology/National Comprehensive Cancer Network quality measures. J Clin Oncol. 2008, 26: 3631-3637. 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5068.

Draskovic I, Vernooij-Dassen M, Verhey F, Scheltens P, Rikkert MO: Development of quality indicators for memory clinics. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008, 23: 119-128. 10.1002/gps.1848.

Estes NA, Halperin JL, Calkins H, Ezekowitz MD, Gitman P, Go AS, McNamara RL, Messer JV, Ritchie JL, Romeo SJ: ACC/AHA/Physician Consortium 2008 Clinical Performance Measures for Adults with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation or Atrial Flutter: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures and the Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (Writing Committee to Develop Clinical Performance Measures for Atrial Fibrillation) Developed in Collaboration with the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008, 51: 865-884. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.006.

Forbes SA, Duncan PW, Zimmerman MK: Review criteria for stroke rehabilitation outcomes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997, 78: 1112-1116. 10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90137-4.

Giesen P, Willekens M, Mokkink H, Braspenning J, Van den Bosch W, Grol R: Out-of-hours primary care: development of indicators for prescribing and referring. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007, 19: 289-295. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm027.

Hadorn DC, Baker DW, Kamberg CJ, Brooks RH: Phase II of the AHCPR-sponsored heart failure guideline: translating practice recommendations into review criteria. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1996, 22: 265-276.

Hardy AM, Hadley RA: CCQE (Center for Clinical Quality Evaluation) develops quality measures for AHCPR pain guideline. QRC Advis. 1995, 11: 1-8.

Hermanides HS, Hulscher ME, Schouten JA, Prins JM, Geerlings SE: Development of quality indicators for the antibiotic treatment of complicated urinary tract infections: a first step to measure and improve care. Clin Infect Dis. 2008, 46: 703-711. 10.1086/527384.

Hermens RPMG, Ouwens MMTJ, Vonk-Okhuijsen SY, van der Wel Y, Tjan-Heijnen VCG, van den Broek LD, Ho VKY, Janssen-Heijnen MLG, Groen HJM, Grol RPTM, Wollersheim HCH: Development of quality indicators for diagnosis and treatment of patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a first step toward implementing a multidisciplinary, evidence-based guideline. Lung Cancer. 2006, 54: 117-124. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.07.001.

James PA, Cowan TM, Graham RP, Majeroni BA, Fox CH, Jaen CR: Using a clinical practice guideline to measure physician practice: translating a guideline for the management of heart failure. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1997, 10: 206-212.

Kongnyuy EJ, van den Broek N: Criteria for clinical audit of women friendly care and providers' perception in Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2008, 8: 28-10.1186/1471-2393-8-28.

Krumholz HM, Anderson JL, Brooks NH, Fesmire FM, Lambrew CT, Landrum MB, Weaver WD, Whyte J, Bonow RO, Bennett SJ: ACC/AHA clinical performance measures for adults with ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures (Writing Committee to Develop Performance Measures on ST-Elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction). Circulation. 2006, 113: 732-761. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.172860.

Lee DS, Tran C, Flintoft V, Grant FC, Liu PP, Tu JV, Canadian Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Team/Canadian Cardiovascular Society: CCORT/CCS quality indicators for congestive heart failure care. Can J Cardiol. 2003, 19: 357-364.

MacLean CH, Saag KG, Solomon DH, Morton SC, Sampsel S, Klippel JH: Measuring quality in arthritis care: methods for developing the arthritis foundation's quality indicator set. Arthritis Care Res. 2004, 51: 193-202. 10.1002/art.20248.

Martirosyan L, Braspenning J, Denig P, de Grauw WJ, Bouma M, Storms F, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM: Prescribing quality indicators of type 2 diabetes mellitus ambulatory care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008, 17: 318-323. 10.1136/qshc.2007.024224.

Mourad SM, Hermens RPMG, Nelen WLDM, Braat DDM, Grol RPTM, Kremer JAM: Guideline-based development of quality indicators for subfertility care. Hum Reprod. 2007, 22: 2665-2672. 10.1093/humrep/dem215.

Nijkrake MJ, Keus SH, Ewalds H, Overeem S, Braspenning JC, Oostendorp RA, Hendriks EJ, Bloem BR, Munneke M: Quality indicators for physiotherapy in Parkinson's disease. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2009, 45: 239-245.

Ouwens M, Hermens R, Hulscher M, Vonk-Okhuijsen S, Tjan-Heijnen V, Termeer R, Marres H, Wollersheim H, Grol R: Development of indicators for patient-centred cancer care. Support Care Cancer. 2010, 18: 121-130. 10.1007/s00520-009-0638-y.

Ouwens MM, Marres HA, Hermens RR, Hulscher MM, van den Hoogen FJ, Grol RP, Wollersheim HC: Quality of integrated care for patients with head and neck cancer: development and measurement of clinical indicators. Head Neck. 2007, 29: 378-386. 10.1002/hed.20532.

Radtke MA, Reich K, Blome C, Kopp I, Rustenbach SJ, Schafer I, Augustin M: Evaluation of quality of care and guideline-compliant treatment in psoriasis. Development of a new system of quality indicators. Dermatology. 2009, 219: 54-58. 10.1159/000218161.

Redberg RF, Benjamin EJ, Braun LT, Goff DC, Havas S, Labarthe DR, Limacher MC, Lloyd-Jones DM, Mora S, Pearson TA, Radford MJ, Smetana GW, Spertus JA, Swegler EW, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Society for Women's Health Research: ACCF/AHA 2009 performance measures for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: A report of the american college of cardiology foundation/american heart association task force on performance measures (writing committee to develop performance measures for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease): Developed in collaboration with the american academy of family physicians. Circulation. 2009, 120: 1296-1336.

Schouten JA, Hulscher ME, Wollersheim H, Braspennning J, Kullberg BJ, van der Meer JW, Grol RP: Quality of antibiotic use for lower respiratory tract infections at hospitals: (how) can we measure it?. Clin Infect Dis. 2005, 41: 450-460. 10.1086/431983.

Sugarman JR, Frederick PR, Frankenfield DL, Owen WF, McClellan WM: Dialysis outcomes quality initiative clinical practice guidelines: Developing clinical performance measures based on the dialysis outcomes quality initiative clinical practice guidelines: process, outcomes, and implications. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003, 42: 806-812. 10.1016/S0272-6386(03)00867-9.

Thomas RJ, King M, Lui K, Oldridge N, Pina IL, Spertus J: AACVPR/ACC/AHA 2007 performance measures on cardiac rehabilitation for referral to and delivery of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention services. Circulation. 2007, 116: 1611-1642.

Tu JV, Khalid L, Donovan LR, Ko DT: Indicators of quality of care for patients with acute myocardial infarction. Can Med Assoc J. 2008, 179: 909-915. 10.1503/cmaj.080749.

Van Den Boogaard E, Goddijn M, Leschot NJ, van der Veen F, Kremer JAM, Hermens RPMG: Development of guideline-based quality indicators for recurrent miscarriage. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010, 20: 267-273. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2009.11.016.

van Hulst LT, Fransen J, den Broeder AA, Grol R, van Riel PL, Hulscher ME: Development of quality indicators for monitoring of the disease course in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009, 68: 1805-1810. 10.1136/ard.2009.108555.

Wang CJ, McGlynn EA, Brook RH, Leonard CH, Piecuch RE, Hsueh SI, Schuster MA: Quality-of-care indicators for the neurodevelopmental follow-up of very low birth weight children: results of an expert panel process. Pediatrics. 2006, 117: 2080-2092. 10.1542/peds.2005-1904.

Yazdany J, Panopalis P, Gillis JZ, Schmajuk G, MacLean CH, Wofsy D, Yelin E: A quality indicator set for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 61: 370-377. 10.1002/art.24356.

Advani A, Goldstein M, Shahar Y, Musen MA: Developing quality indicators and auditing protocols from formal guideline models: knowledge representation and transformations. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. 2003, 11-15.

Duffy FF, Narrow W, West JC, Fochtmann LJ, Kahn DA, Suppes T, Oldham JM, McIntyre JS, Manderscheid RW, Sirovatka P, Regier D: Quality of care measures for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Q. 2005, 76: 213-230. 10.1007/s11126-005-2975-4.

Golden WE, Hermann RC, Jewell M, Brewster C: Development of evidence-based performance measures for bipolar disorder: overview of methodology. J Psychiatr Pract. 2008, 14 (Suppl 2): 18-30.

LaClair BJ, Reker DM, Duncan PW, Horner RD, Hoenig H: Stroke care: a method for measuring compliance with AHCPR guidelines. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001, 80: 235-242. 10.1097/00002060-200103000-00017.

The AGREE Instrument. [http://www.agreetrust.org/resource-centre/the-original-agree-instrument/]

Brook RH, Chassin MR, Fink A, Solomon DH, Kosecoff J, Park RE: A method for the detailed assessment of the appropriateness of medical technologies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1986, 2: 53-63. 10.1017/S0266462300002774.

Brook RH: Assessing the appropriateness of care - its time has come. JAMA. 2009, 302: 997-998. 10.1001/jama.2009.1279.

Kopp IB, Selbmann HK, Koller M: Consensus development in evidence-based guidelines: from myths to rational strategies. Z ärztl Fortbild Qual Gesundh wes. 2007, 101: 89-95.

Center for Reviews and Dissemination: Systematic Reviews CRD's Guidance for Undertaking Systematic Reviews in Health Care. 2009, York: CRD, University of York

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following people for their invaluable help during this review: Friederike Schaefer (University of Lübeck) for her superb help during the literature screening; for their support during the literature retrieval, Bettina Dittrich, Julia Siebert (both Institute for Social Medicine, University of Lübeck), and Sabine Wedemeyer (University Library, University of Lübeck); and Freya von Manteuffel for her thorough copyediting of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

TK designed the study; performed literature search and screening, literature retrieval, and data extraction and interpretation; and wrote and revised the paper. EB contributed to the initial study idea, study design, and data interpretation; critically revised the article for important intellectual content; and read and approved the final draft. MS contributed to initial study idea, study conception and design, and data interpretation; critically revised the article for important intellectual content; and read and approved the final draft.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kötter, T., Blozik, E. & Scherer, M. Methods for the guideline-based development of quality indicators--a systematic review. Implementation Sci 7, 21 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-21

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-21