Abstract

Background

Barley and bread wheat show large differences in frequencies of Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) as determined from genome-wide studies. These frequencies have been estimated as 2.4-3 times higher in the entire barley genome than within each diploid genomes of wheat (A, B or D). However, barley SNPs within individual genes occur significantly more frequently than quoted. Differences between wheat and barley are based on the origin and evolutionary history of the species. Bread wheat contains rarer SNPs due to the double genetic ‘bottle-neck’ created by natural hybridisation and spontaneous polyploidisation. Furthermore, wheat has the lowest level of useful SNP-derived markers while barley is estimated to have the highest level of polymorphism.

Results

Different strategies are required for the development of suitable molecular markers in these cereal species. For example, SNP markers based on high-throughput technology (Infinium or KASP) are very effective and useful in both barley and bread wheat. In contrast, Cleaved Amplified Polymorphic Sequences (CAPS) are more widely and successfully employed in small-scale experiments with highly polymorphic genetic regions containing multiple SNPs in barley, but not in wheat. However, preliminary ‘in silico’ search databases for assessing the potential value of SNPs have yet to be developed.

Conclusions

This mini-review summarises results supporting the development of different strategies for the application of effective SNP and CAPS markers in wheat and barley.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP), the substitution of a single nucleotide in any part of the genome as a result of natural mutation, has become one of the most powerful tools in molecular biology (Reviewed in [1]). Large-scale genome reorganisations such as translocations, duplications or substantial deletions/insertions are very often eliminated by natural selection, except in rare cases where the change provides a direct benefit for the mutated organisms. One example of this is plant genome polyploidisation in adverse environments (Reviewed in [2]). In contrast, SNPs as point mutations can be evolutionally neutral and escape the pressure of natural selection if it occurs in non-coding regions or does not affect amino acid sequence of the encoded polypeptides. Subsequently, SNPs have become widely distributed in genomes of all living organisms (Reviewed in [3]).

In plants, SNPs have a particularly important application as molecular markers reflecting both natural genetic variability and a genetic drift created by breeders during the course of crops improvement (Reviewed in [4–9]). The application of SNP markers has shown rapid progress in recent years that technological advances and the expansion of low cost services have made sequencing a routine practice widely available to scientists. The presence of SNPs among parents of segregating populations or in a panel of genotypes is important factor when choosing the most suitable strategy for genetic polymorphism analysis. Many different types of molecular markers are based on SNP identification and each has accompanying advantages and disadvantages. In the present mini-review we compare high-throughput technology of SNP markers and Cleaved Amplified Polymorphic Sequences (CAPS) markers in regard to their application in the two important cereal crops of wheat and barley.

High-throughput SNP analysis: Illumina vs. KASP technology

The work of many researchers focuses on individual genes that are of significance to their area of study. Such Gene of Interest (GOI) can be sequenced and genetic polymorphism within the sequences can then be identified and analysed manually. However, large-scale Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) is now achievable through robotics high-throughput technology. Thousands of SNP markers can be identified at a time and analyse hundreds of accessions. Initial applications of SNP markers were based on the high-throughput platform from the American company Illumina that was very suitable for plants [5]. Our own experience of Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) with 9 K Illumina Infinium SNP array in wheat [10] confirmed the supreme effectiveness of this technology in crops [11]. In wheat, the numbers of available SNP markers is growing rapidly jumping from 90 K as recorded by the new Infinium [12, 13] to 500 K and 4 M in Illumina shortgun WGS array [14, 15].

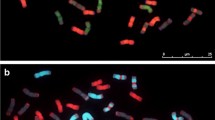

Many of the SNP markers identified by Illumina Infinium or shortgut WGS arrays have already been mapped out in the chromosomes. In conjunction with the easy to use and publicly available software FlapJack (http://www.hutton.ac.uk/research/groups/information-and-computational-sciences/tools), SNP can be clearly visualised in the linear arrangement that allows a direct comparison of genotypes, as presented earlier [10].

Despite the wide distribution of NGS Infinium and WGS shortgun from Illumina, the British company LGC Genomics has developed an alternative high-throughput technology named KASPar or KASP [16]. “The KASP assay utilizes a novel homogeneous fluorescent genotyping system” [16], that claims to provide greater flexibility for researchers. KASP technology has been successfully utilised for the SNP analysis of pigeonpea [17], peanut [18] and soybean [19]. The comparison of KASP markers to other methods of SNP genotyping has been reviewed in: [6–9, 11].

High-throughput methods cannot be easily adapted to the study of GOI, where SNPs must be found and assessed on a very short fragment of the coding region. Most often, researchers will instead sequence the full gene and later amplify a certain genetic fragment manually. The only option for the use of high-throughput automatic systems is to study multiple accessions or progeny segregations using a very limited number of primer-sets. In this case, a service providing a molecular analysis of DNA samples using various high-throughput SNP technologies can be applied.

CAPS markers as an example of manual SNP analysis

Many small-scale laboratories are focused on a single or very limited numbers of GOI. During sequencing, there can be no guarantee that an identified SNP will be suitable for use as a molecular marker. In plant biology, a common practice is to design one primer so that the 3’-end is exactly located on the SNP position. Depending on the match or mismatch of the SNP in the 3’-end of the primer, a positive or null-band from PCR amplification will then be produced. This approach is named Allele-Specific PCR (AS-PCR) and has been successfully used in plant biology [11, 20].

However, if an SNP occurs within the recognition site of a restriction enzyme, it is much easier to use CAPS markers. The digestion of PCR products and subsequent separation of the fragments in agarose gel is a simple approach that can be carried out in any laboratory with basic molecular equipment, achieving accurate and clear results. The recent book [21] and review [22] compiled and discussed hundreds of examples of CAPS markers and their application in plant biology.

SNP and CAPS in wheat and barley

The high-throughput technology of SNP markers is very effective in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). As mentioned above, 9K and 90K SNP arrays are now routinely employed for bread wheat analyses [10, 11, 13, 23]. In durum wheat, the range of applied SNP markers is even wider including: 2.6K [24], 26K [25] and 90K [12]. Most recently, a 9M SNP array in a single homeologous group of chromosome 7 in bread wheat has been reported [15]. Clearly, SNP markers continue to be of great value to plant genetic research and the true extent of their worth may not yet be apparent.

In cultivated barley (Hordeum vulgare L.), the reported number of SNP markers is quite variable: 1.5K [26], 4.5K [27], 9K [28], and 22K [29]. The barley genome is estimated to be about 5.1 Gb with 26,159 ‘high-confidence’ genes recognised [30]. This is smaller than each of three genomes of hexaploid wheat at an estimated total of 17 Gb, with 124,201 identified gene loci [31]. Nevertheless, high-throughput technology using SNP markers is also very effective in barley [26–29], so we can conclude that there is no appreciable difference with SNP marker application in wheat and barley.

However, the same cannot be applied to CAPS markers. Many reports have indicated that the application of CAPS markers is much simpler and more productive in barley than in wheat (Reviewed in [20, 22]). A number of groups have shown success in developing CAPS markers for Marker-assisted selection in barley [32–34]. In bread wheat, CAPS markers are reportedly much rarer [35–37] but they have been found in tetraploid Triticum dicoccoides [38] and Aegilops tauschii Coss, the wild progenitor of D genome [39].

The difference in the expected frequencies in both crops can be illustrated by the rather unusual example of restriction enzyme selection. In this case, scientists working with a specific GOI in barley did not sequence the amplified PCR fragments at all. In the absence of a genetic sequence, Řepková et al. [40] digested a 511-bp PCR product amplified from the powdery mildew resistance gene, Mla, with 12 different restriction enzymes. Presumably, the choice of restriction enzymes was based on their availability in the laboratory and was otherwise random. Two restriction enzymes (DraI and HpaII), with completely non-related recognition sites, revealed a polymorphism between resistant and sensitive barley plants. HpaII was chosen for CAPS marker development, eventually leading to its successful application [40]. This demonstrates how effective CAPS markers can be easily identified using even an economically non-optimal method in barley. However, such a strategy is most unlikely to be successful in wheat, where the occurrence of SNPs is much rarer, and thus is more similar to the probability of winning ‘the Jackpot’ in a lottery. In wheat, a known sequence with one or more identified SNPs is essential for CAPS markers development.

The differences in SNP and CAPS markers in barley and wheat are summarised in Table 1a. SNPs are used as high-throughput derived markers, effective in both wheat and barley. However, CAPS markers, most suitable for manual application, showed excellent results in barley but very poor results in wheat (Reviewed in [20]). A topic of great interest when examining the differences observed in the frequencies of SNPs in both barley and wheat is to debate the possible biological origins behind these differences, as is discussed in the following section.

Comparison of SNP frequencies in barley and wheat

In barley, the SNP frequencies determined from genome-wide studies or at least multiple gene surveys record one SNP per 240 bp [41, 42], per 200 bp [43] and per 189 bp [44]. In contrast, barley SNPs within individual barley GOI may be significantly more frequent than quoted. For example, roughly one SNP is present per 64 bp in the β-amylase Bmy1 gene [45], per 42 bp in the scald resistance Rrs2 gene [46], per 29 bp in aluminium tolerance gene, HvMATE1 [47], per 27 bp in the intronless Isa gene [48], and per 7 bp in the leaf rust resistance Rph7 gene [49] (Table 1b).

Hexaploid wheat is an allopolyploid species with three different genomes (A, B and D). SNPs identified among homoeologous sequences in these three genomes are named ‘false SNP’ [24] and reflect interspecific genetic differences among ancestors of the three genomes in wheat. The frequencies for such ‘false SNP’ in bread whet are quite high and are reported as one SNP per 20 bp [50], per 24 bp [51] and up to 61 bp [52]. In contrast, intervarietal polymorphisms among homologous chromosomes of different genotypes are named ‘true SNPs’ [24]. An entire wheat genome analysis of bread wheat reported one ‘true SNP’ per 540-569 bp [11, 12, 51] within one of three genomes. Interestingly, the SNP frequency in GOI was relatively similar to the number recorded in the entire genome: one ‘true SNP’ per 335 bp in 21 studied genes [53], one SNP per 556 bp in the Grain Protein Content B1 gene, GPC-B1 [54], and one SNP per 613 bp in 13 studied genes [55] (Table 1b).

SNP marker analysis in barley and bread wheat (Table 1a) to detect ‘true’ SNP frequencies in entire genomes (Table 1b), has ascertained some 2.4-3-fold more SNPs in barley compared to wheat. Despite a high overall efficiency in high-throughput SNP analyses, when considering specific GOI the frequencies of SNPs are very different (Table 1b), namely 5.2-87.6-fold higher in the genome of barley than wheat. Furthermore, it was reported that wheat has the lowest level of useful SNP-derived markers while barley has been estimated to contain the highest level of polymorphism [52]. Because the detection of SNPs in GOI is the most critical step for CAPS markers developments, we can conclude that the enormous differences in SNP frequencies in GOI between barley and bread wheat is the main reason for variability in the results of CAPS in these crops (Table 1a). The biological basis for the phenomenon is likely based upon the evolutionary origin of both crops.

Evolutionary differences in wheat and barley

Genetic differences between wheat and barley arise from the individual origins and evolutionary history of both species. Bread wheat contains rare SNPs as a result of the double genetic ‘bottle-neck’ created by the natural hybridisation and spontaneous polyploidisation that led to a significant reduction of genetic polymorphisms. Recent data has revealed that the initial hybridisation between progenitors of A and B genomes occurred between 0.52-0.82 million years ago [56], significantly earlier than was initially proposed [57, 58]. Since that time, A and B genomes have co-evolved in the genomes of tetraploid wheat. The second event of hybridisation with Aegilops tauschii (D genome) is estimated to have taken place about 8-9 thousand years ago [59–61].

The size of each separate genome, A, B or D, in bread wheat is comparable to the size of the genome in diploid barley. However, the percentage of non-coding genetic regions on the chromosomes with repetitive elements is dramatically different in bread wheat and barley, accounting for more than 85 % of the wheat genome [11]. The domestication of wheat and barley occurred in parallel in ancient times, but lower frequencies of SNPs were more common in bread wheat, while domesticated barley remains more polymorphic species [59, 61].

Cultivated barley also experienced a genetic ‘bottle-neck’ through domestication, but the breeding pressure was less strong than in wheat resulting in more frequent polymorphisms [27]. The majority of the genetic variation in genepool of modern elite barley genotypes can be assessed with 100-1000’s of robust markers such as SNPs [27]. Therefore, significantly less applied SNP markers in barley revealed similar genetic polymorphism compared to wheat.

Conclusions

In summary, different strategies are required for the development of the most suitable molecular markers in the cereal species. High-throughput technology is very effective for SNP marker development in both bread wheat and barley despite considerable differences in the rate of their occurrence in the entire genomes: 2.4-3-fold more in barley than in each of three genomes of wheat. The potential SNPs for either Infinium or KASP high-throughput technology have to be initially searched ‘in silico’ in different databases following assessment of effective SNPs. Clear differences between barley and bread wheat are shown in the application of manually developed CAPS markers. In barley, the presence of highly polymorphic genetic regions containing multiple SNPs allows the simple development of CAPS in small-scale experiments. However, it is a much harder task to develop CAPS in bread wheat due to significantly lower occurrence of SNPs (5.2-87.6-fold in GOI).

References

Liao PY, Lee KH. From SNPs to functional polymorphism: The insight into biotechnology applications. Biochem Engineer J. 2010;49(2):149–58.

Moghe GD, Shiu SH. The causes and molecular consequences of polyploidy in flowering plants. In: Fox CW, Mousseau TA, editors. Year in Evolutionary Biology. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 1320. Oxford: Blackwell Science Publisher; 2014. p. 16–34.

Perkel J. SNP genotyping: six technologies that keyed a revolution. Nat Methods. 2008;5(5):447–53.

Edwards D, Batley J. Plant genome sequencing: applications for crop improvement. Plant Biotech J. 2010;8(1):2–9.

Peatman E. SNP genotyping platforms. In: Liu Z, editor. Next Generation Sequencing and Whole Genome Selection in Aquaculture. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2011. p. 123–32.

Kumar S, Banks TW, Cloutier S. SNP Discovery through Next-generation sequencing and its applications. Intern J Plant Genomics. 2012;2012:831460.

Kumpatla SP, Buyyarapu R, Abdurakhmonov IY, Mammadov JA. Genomics-assisted plant breeding in the 21st century: Technological advances and progress. In: Abdurakhmonov I, editor. Plant Breeding. Rijeka: InTech; 2012. p. 131–84.

Semagn K, Babu R, Hearne S, Olsen M. Single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping using Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR (KASP): overview of the technology and its application in crop improvement. Mol Breed. 2014;33(1):1–14.

Thomson MJ. High-throughput snp genotyping to accelerate crop improvement. Plant Breed Biotech. 2014;2(3):195–212.

Shavrukov Y, Suchecki R, Eliby S, Abugalieva A, Kenebayev S, Langridge P. Application of next-generation sequencing technology to study genetic diversity and identify unique SNP markers in bread wheat from Kazakhstan. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:258.

Paux E, Sourdille P, Mackay I, Feuillet C. Sequence-based marker development in wheat: advances and applications to breeding. Biotech Advan. 2012;30(5):1071–88.

Avni R, Nave M, Eilam T, Sela H, Alekperov C, Peleg Z, et al. Ultra-dense genetic map of durum wheat x wild emmer wheat developed using the 90K iSelect SNP genotyping assay. Mol Breed. 2014;34(4):1549–62.

Wang S, Wong D, Forrest K, Allen A, Chao S, Huang BE, et al. Characterization of polyploid wheat genomic diversity using a high-density 90 000 single nucleotide polymorphism array. Plant Biotech J. 2014;12(6):787–96.

Lai K, Duran C, Berkman PJ, Lorenc MT, Stiller J, Manoli S, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism discovery from wheat next-generation sequence data. Plant Biotech J. 2012;10(6):743–49.

Lai K, Lorenc MT, Lee HC, Berkman PJ, Bayer PE, Visendi P, et al. Identification and characterization of more than 4 million intervarietal SNPs across the group 7 chromosomes of bread wheat. Plant Biotech J. 2015;13(1):97–104.

He C, Holme J, Anthony J. SNP genotyping: the KASP assay. In: Fleury D, Whitford R, editors. Crop Breeding: Methods and Protocols, Methods in Molecular Biology, vol. 1145. New York: Springer; 2014. p. 75–86.

Saxena RK, Penmetsa RV, Upadhyaya HD, Kumar A, Carrasquilla-Garcia N, Schlueter JA, et al. Large-scale development of cost-effective single-nucleotide polymorphism marker assays for genetic mapping in pigeonpea and comparative mapping in legumes. DNA Res. 2012;19(6):449–61.

Khera P, Upadhyaya HD, Pandey MK, Roorkiwal M, Sriswathi M, Janila P, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism-based genetic diversity in the reference set of peanut (Arachis spp.) by developing and applying cost-effective kompetitive allele specific polymerase chain reaction genotyping assays. Plant Genome. 2013;6(3): doi:10.3835/plantgenome2013.06.0019.

Yuan J, Wen Z, Gu C, Wang D. Introduction of high throughput and cost effective SNP genotyping platforms in soybean. Plant Genet Genomics Biotech. 2014;2(1):90–4.

Shavrukov Y. Why are the development and application of CAPS markers so different in bread wheat compared to barley? In: Shavrukov Y, editor. Cleaved Amplified Polymorphic Sequences (CAPS) Markers in Plant Biology. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2014. p. 211–32.

Shavrukov Y, editor. Cleaved Amplified Polymorphic Sequences (CAPS) Markers in Plant Biology. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2014.

Shavrukov YN. CAPS markers in plant biology. Vavilov J Genet Breed. 2015;19(2):205–13.

Turuspekov Y, Plieske J, Ganal M, Akhunov E, Abugalieva S. Phylogenetic analysis of wheat cultivars in Kazakhstan based on the wheat 90 K single nucleotide polymorphism array. Plant Genetic Resources. 2015. doi:10.1017/S1479262115000325.

Trebbi D, Maccaferri M, Heer P, Sørensen A, Giuliani S, Salvi S, et al. High-throughput SNP discovery and genotyping in durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.). Theor Appl Genet. 2011;123(4):555–69.

Maccaferri M, Ricci A, Salvi S, Milner SG, Noli E, Martelli PL, et al. A high-density, SNP-based consensus map of tetraploid wheat as a bridge to integrate durum and bread wheat genomics and breeding. Plant Biotech J. 2015;13(5):648–63.

Sallam AH, Endelman JB, Jannink JL, Smith KP. Assessing genomic selection prediction accuracy in a dynamic barley breeding population. Plant Genome. 2015;8(1): doi:10.3835/plantgenome2014.05.0020.

Comadran J, Ramsay L, MacKenzie K, Hayes P, Close TJ, Muehlbauer G, et al. Patterns of polymorphism and linkage disequilibrium in cultivated barley. Theor Appl Genet. 2011;122(3):523–31.

Wehner GG, Balko CC, Enders MM, Humbeck KK, Ordon FF. Identification of genomic regions involved in tolerance to drought stress and drought stress induced leaf senescence in juvenile barley. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:125.

Close TJ, Bhat PR, Lonardi S, Wu Y, Rostoks N, Ramsay L, et al. Development and implementation of high-throughput SNP genotyping in barley. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:582.

The International Barley Genome Sequencing Consortium. A physical, genetic and functional sequence assembly of the barley genome. Nature. 2012;491(7426):711–6.

Eversole K, Feuillet C, Mayer KFX, Rogers J. Slicing the wheat genome. Science. 2014;345(6194):285–7.

Hofmann K, Silvar C, Casas AM, Herz M, Büttner B, Gracia MP, et al. Fine mapping of the Rrs1 resistance locus against scald in two large populations derived from Spanish barley landraces. Theor Appl Genet. 2013;126(12):3091–102.

Iimure T, Zhou TS, Hoki T. Development of CAPS markers and its use for malting barley breeding. In: Shavrukov Y, editor. Cleaved Amplified Polymorphic Sequences (CAPS) Markers in Plant Biology. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2014. p. 151–65.

Ui H, Sameri M, Pourkheirandish M, Chang MC, Shimada H, Stein N, et al. High-resolution genetic mapping and physical map construction for the fertility restorer Rfm1 locus in barley. Theor Appl Genet. 2015;128(2):283–90.

Beckie HJ, Warwick SI, Hall LM, Harker KN. Pollen-mediated gene flow in wheat fields in Western Canada. AgBioForum. 2012;15(1):36–43.

Okoń S, Kowalczyk K, Miazga D. Identification of Ppd-B1 alleles in common wheat cultivars by CAPS marker. Russ J Genet. 2012;48(5):532–7.

Jiang Y, Jiang Q, Hao C, Hou J, Wang L, Zhang H, et al. A yield-associated gene TaCWI, in wheat: its function, selection and evolution in global breeding revealed by haplotype analysis. Theor Appl Genet. 2015;128(1):131–43.

Raats D, Yaniv E, Distelfeld A, Ben-David R, Shanir J, Bocharova V, et al. Application of CAPS markers for genomic studies in wild emmer wheat. In: Shavrukov Y, editor. Cleaved Amplified Polymorphic Sequences (CAPS) Markers in Plant Biology. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2014. p. 31–60.

Azhaguvel P, Rudd JC, Ma Y, Luo MC, Weng Y. Fine genetic mapping of greenbug aphid-resistance gene Gb3 in Aegilops tauschii. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;124(3):555–64.

Řepková J, Dreiseitl A, Lízal P. New CAPS marker for selection of barley powdery mildew resistance gene in the Mla locus. Cereal Res Comm. 2009;37(1):93–9.

Kota R, Varshney RK, Thiel T, Dehmer KJ, Graner A. Generation and comparison of EST-derived SSRs and SNPs in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Hereditas. 2001;135(2-3):145–51.

Duran C, Appleby N, Vardy M, Imelfort M, Edwards D, Barley J. Single nucleotide polymorphism discovery in barley using autoSNPdb. Plant Biotech J. 2009;7(4):326–33.

Rostoks N, Mudie S, Cardle L, Russell J, Ramsay L, Booth A, et al. Genome-wide SNP discovery and linkage analysis in barley based on genes responsive to abiotic stress. Mol Genet Genomics. 2005;274(5):515–27.

Kanazin V, Talbert H, See D, DeCamp P, Nevo E, Blake T. Discovery and assay of single-nucleotide polymorphism in barley (Hordeum vulgare). Plant Mol Biol. 2002;48(5-6):529–37.

Zhang WS, Li X, Liu JB. Genetic variation of Bmy1 alleles in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) investigated by CAPS analysis. Theor Appl Genet. 2007;114(6):1039–50.

Hanemann A, Schweizer GF, Cossu R, Wicker T, Röder MS. Fine mapping, physical mapping and development of diagnostic markers for the Rrs2 scald resistance gene in barley. Theor Appl Genet. 2009;119(8):1507–22.

Bian M, Jin XL, Broughton S, Zhang XQ, Zhou GF, Zhou MX, et al. A new allele of acid soil tolerance gene from a malting barley variety. BMC Genetics. 2015;16:92. doi:10.1186/s12863-015-0254-4.

Bundock PC, Henry RJ. Single nucleotide polymorphism, haplotype diversity and recombination in the Isa gene of barley. Theor Appl Genet. 2004;109(3):543–51.

Graner A, Streng S, Drescher A, Jin Y, Borovkova I, Steffenson BJ. Molecular mapping of the leaf rust resistance gene Rph7 in barley. Plant Breed. 2000;119(5):389–92.

Jehan T, Lakhanpaul S. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) – Methods and applications in plant genetics: A review. Indian J Biotech. 2006;5:435–59.

Somers DJ, Kirkpatrick R, Moniwa M, Walsh A. Mining single-nucleotide polymorphism from hexaploid wheat ESTs. Genome. 2003;46(3):431–7.

Barker GLA, Edwards KJ. A genome-wide analysis of single nucleotide polymorphism diversity in the world’s major cereal crops. Plant Biotech J. 2009;7(4):318–25.

Ravel C, Praud S, Murigneux A, Canaguier A, Sapet F, Samson D, et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphism frequency in a set of selected lines of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Genome. 2006;49(9):1131–9.

Trick M, Adamski N, Mugford SG, Jiang CC, Febrer M, Uauy C. Combining SNP discovery from next-generation sequencing data with bulked segregant analysis (BSA) to fine-map genes in polyploid wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:14.

Schnurbusch T, Collins NC, Eastwood RF, Sutton T, Jefferies SP, Langridge P. Fine mapping and targeted SNP survey using rice-wheat gene colinearity in the region of the Bo1 boron toxicity tolerance locus of bread wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2007;115(4):451–61.

Marcussen T, Sandve SR, Heier L, Spannagl M, Pfeifer M, Jakobsen KS, et al. Ancient hybridizations among the ancestral genomes of bread wheat. Science. 2014;345(6194):1250092.

Huang S, Sirikhachornkit A, Su X, Faris J, Gill B, Haselkorn R, et al. Genes encoding plastid acetyl-CoA carboxylase and 3-phosphoglycerate kinase of the Triticum/Aegilops complex and the evolutionary history of polypoid wheat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(12):8133–8.

Dvorak J, Akhunov ED. Tempos of gene locus deletions and duplications and their relationship to recombination rate during diploid and polyploid evolution in the Aegilops-Triticum alliance. Genetics. 2005;171(1):323–32.

Salamini F, Ozkan H, Brandolini A, Schäfer-Pregl R, Martin W. Genetics and geography of wild cereal domestication in the near east. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3(6):429–41.

Gill BS, Appels R, Botha-Oberholster AM, Buell CR, Bennetzen JL, Chalhoub B, et al. A workshop report on wheat genome sequencing: International genome research on wheat consortium. Genetics. 2004;168(2):1087–96.

Peng JH, Sun D, Nevo E. Domestication evolution, genetics and genomics in wheat. Mol Breed. 2011;28(3):281–301.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by grants from Hermon Slade Foundation (Australia), Wheat Cereal Trust (South Africa) and Ministry of Education and Science (Kazakhstan). We also thank Carly Schramm for critical comments in the manuscript.

Declarations

The publication of this paper has been financially supported by the grant from Kazakhstan.

This article has been published as part of BMC Plant Biology Volume 16 Supplement 1, 2015: Selected articles from PlantGen 2015 conference: Plant biology. The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://www.biomedcentral.com/bmcplantbiol/supplements/16/S1 .

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Author declares no competing interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Shavrukov, Y. Comparison of SNP and CAPS markers application in genetic research in wheat and barley. BMC Plant Biol 16 (Suppl 1), 11 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-015-0689-9

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-015-0689-9