Abstract

Background

Symbiotic interactions between insects and bacteria have been associated with a vast variety of physiological, ecological and evolutionary consequences for the host. A wide range of bacterial communities have been found in association with the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) (Diptera: Tephritidae), an important pest of cultivated fruit in most regions of the world. We evaluated the diversity of gut bacteria in B. dorsalis specimens from several populations in Kenya and investigated the roles of individual bacterial isolates in the development of axenic (germ-free) B. dorsalis fly lines and their responses to the entomopathogenic fungus, Metarhizium anisopliae.

Results

We sequenced 16S rRNA to evaluate microbiomes and coupled this with bacterial culturing. Bacterial isolates were mono-associated with axenic B. dorsalis embryos. The shortest embryonic development period was recorded in flies with an intact gut microbiome while the longest period was recorded in axenic fly lines. Similarly, larval development was shortest in flies with an intact gut microbiome, in addition to flies inoculated with Providencia alcalifaciens. Adult B. dorsalis flies emerging from embryos that had been mono-associated with a strain of Lactococcus lactis had decreased survival when challenged with a standard dosage of M. anisopliae ICIPE69 conidia. However, there were no differences in survival between the germ-free lines and flies with an intact microbiome.

Conclusions

These findings will contribute to the selection of probiotics used in artificial diets for B. dorsalis rearing and the development of improved integrated pest management strategies based on entomopathogenic fungi.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

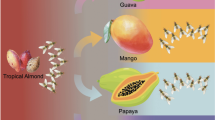

The oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) (Diptera: Tephritidae) is a pest of cultivated fruit and has been recorded in various locations across Asia, Africa, and North America and recently in Europe [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Since this species is considered a high risk quarantine pest, infestation with this pest has significant implications for production, trade and socio-economic aspects of affected countries [10,11,12,13].

The symbiotic association between insects and bacteria has important implications for insect physiology, ecology and evolution [14]. Therefore, understanding symbiont-host interactions in diverse groups of insects has become a priority. For major pest species, such as B. dorsalis, identification of associated bacterial communities can provide useful insights into biological characteristics and lead to improved control methods.

The ability of bacterial symbionts to influence the development of their host and to modulate the host’s response to entomopathogenic fungi has been demonstrated in a number of insect species. Endosymbionts as well as gut bacteria have been shown to affect the durations of embryonic and post-embryonic development periods [15,16,17,18,19,20]. Such associations have been linked to additional roles such as provision of essential amino acids and vitamins by bacteria to their insect hosts [18, 21]. In addition, symbiotic bacteria have been reported to exhibit inhibitory capabilities against fungal infections in Drosophila melanogaster [22, 23], ants [24], wasps [25] aphids [26,27,28] and beetles [29]. These capabilities could be effected via production of antifungal metabolites [30, 31] or other unknown mechanisms. For B. dorsalis, the entomopathogenic fungus, Metarhizium anisopliae (Metchnikoff) Sorokin is often applied as a biopesticide [32,33,34,35,36]. However, limited information is available regarding whether bacterial symbionts influence the response of B. dorsalis to this fungus.

A number of studies have investigated the diversity and structure of the gut microbiome of B. dorsalis [1, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. The specific roles of certain bacterial isolates from B. dorsalis have also been reported. For example, isolates have been shown to directly affect the nutrient ingestion and foraging behavior of B. dorsalis [39]. Some bacterial isolates, including Enterococcus sp., Microbacterium, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Lactococcus lactis, have been found to influence the developmental time, morphological parameters and survival of the oriental fruit fly [37]. Bacterial insolates have also been found to influence mate-selection behavior in B. dorsalis [46]. Bactrocera dorsalis also benefits from the ability of some of its gut associated bacteria to break down toxicants, which has been linked to insecticide resistance in this species [43, 47].

In this study, we isolated some common bacterial species associated with B. dorsalis populations in Kenya and investigated their roles in the development of immature stages of B. dorsalis. We also evaluated the implications of rearing flies supplemented with single bacterial isolates on the survival of adult flies when exposed to an entomopathogenic fungus.

Results

The microbiomes of B. dorsalis specimens originating from different regions of Kenya were found to be dominated by the bacterial genera: Lactobacillus, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Providencia, Lactococcus and Pantoea amongst several others (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Three genera: Enterobacter, Klebsiella and Serratia (in adult specimens) and Lactobacillus (in larval specimens) were differentially abundant among the sampled locations (Supplementary Fig. 3). The abundance of the detected bacterial genera was found to differ among the sampled locations (Supplementary Fig. 4).

A total of 12 unique bacterial isolates were isolated through culturing of gut homogenates of adult and larval specimens from the five sampled sites: Embu, Muranga, Makueni, Kitui, Nguruman and the icipe laboratory colony. Similar to the 16S sequencing result, several isolates in the Enterobacteriaceae family (Enterobacter cloacae, E. asburiae, E. tabaci, Klebsiella oxytoca, Providencia alcalifaciens and P. rettgeri) were isolated mainly from sites in which high proportions of the respective genera had been detected. In addition, L. lactis strains were isolated from Embu and Nguruman specimens (Supplementary Table 1). Of these, E. cloacae, K. oxytoca, L. lactis, P. alcalifaciens as well as Citrobacter freundii were used to generate mono-associated fly lines.

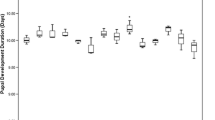

We evaluated developmental and fitness measures such as pupal size and weight in B. dorsalis lines inoculated with the respective bacterial isolates. Significant variations in the time taken for embryos to hatch were recorded between the different B. dorsalis lines (χ2 = 36.15, df = 6, p < 0.001). Embryos of the B. dorsalis lines with an intact microbiome (hereafter referred to as Ut-control) were observed to take the shortest duration to hatch whereas the longest duration was recorded in the axenic line (Fig. 1a). Similarly, the B. dorsalis lines had significantly different durations at larval stage (χ2 = 24.76, df = 6, p < 0.001), with the Ut-control and the P. alcalifaciens line having the shortest duration. (Fig. 1b).

Boxplot of a Embryo hatching time and b Larval development duration of the B. dorsalis lines. Plots with the same letter are not significantly different (Dunn’s p > 0.05). The median is shown as a black line within the box. The edges of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles. Whiskers span 1.5 times the interquartile range. Outliers of individual variables are represented as circles. Untransformed data are shown

We examined the puparia size of inoculated B. dorsalis lines as a proxy for assessing the effects of microbiota members on the host fitness. There was no significant difference in means of puparia lengths among all the fly lines (χ2 = 5.96, df = 6, p = 0.43) (Fig. 2a). Similarly, none of the fly lines exhibited a significant variation in width of puparia (χ2 = 8.43, df = 6, p = 0.21) (Fig. 2b). However, significantly different puparia weights were recorded among the B. dorsalis lines (χ2 = 18.99, df = 6, p = 0.004) except between the K. oxytoca and the P. alcalifaciens lines as well as between the Ut-control and the C. freundii line (Fig. 2c).

Boxplots of puparia (a) lengths (b) widths and (c) weights of the B. dorsalis lines. Plots with the same letter are not significantly different (Dunn’s p > 0.05). The median is shown as a black line within the box. The edges of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles. Whiskers span 1.5 times the interquartile range. Outliers of individual variables are represented as circles. Untransformed data are shown

In addition, we investigated the survival rates of adult flies emerging from the bacterial inoculated B. dorsalis lines and controls, upon infection with the entomopathogenic fungus, Metarhizium anisopliae, ICIPE69. No significant variations in survival were recorded between the axenic control and the Ut-control (χ2 = 0.31, df = 1, p = 0.58). However, survival of the axenic line varied significantly from the L. lactis line (χ2 = 5.33, df = 1, p = 0.02). Although survival of the P. alcalifaciens line did not vary significantly from that of the axenic control (χ2 = 1.67, df = 1, p = 0.20) and the Ut-control (χ2 = 2.60, df = 1, p = 0.11), significant variation in survival was recorded between this line and the K. oxytoca line (χ2 = 4.23, df = 1, p = 0.04) as well as with the L. lactis line (χ2 = 8.64, df = 1, p = 0.003). In addition to the axenic control as aforementioned, the L. lactis line also varied significantly in survival from the C. freundii line (χ2 = 4.12, df = 1, p = 0.04) as shown in Fig. 3. However, survival between the rest of the B. dorsalis lines and controls did not vary significantly (Supplementary Table 2).

Survival comparison between inoculated B. dorsalis lines, post exposure to M. anisopliae as adult flies. a Axenic and Ut-control b P. alcalifaciens line and axenic control c P. alcalifaciens line and Ut-control d P. alcalifaciens and K. oxytoca lines e P. alcalifaciens and L. lactis lines f L. lactis line and axenic control, and g L. lactis and C. freundii lines

The B. dorsalis line inoculated with L. lactis exhibited a significant diminished survival at adult stage (Fig. 3f) whereas the line inoculated with P. alcalifaciens showed a slightly improved survival from days 4 to 7 (Fig. 3b and c) which, however, did not significantly affect the overall survival of this line. We therefore investigated the structure of the gut microbiota of adult flies emerging from these two lines, unexposed to the fungus. The microbiome of 2-day old adult flies from the L. lactis fly line was found to consist mainly of Lactococcus and lesser proportions of other bacterial genera, whereas that of adults from the P. alcalifaciens line was fully colonized by Providencia (Fig. 4). Notably, the observed microbiome compositions at adult stages of the tested lines are highly reflective of the bacterial isolates that were introduced during the immature stages. In the L. lactis mono-associated fly line, we observed a low proportion of other bacterial groups suggesting that very limited re-colonization from other environmental bacteria occurred.

Discussion

The gut microbiome of B. dorsalis derived from different populations in Kenya was found to consist of members that have been reported among the gut microbiota of B. dorsalis in other parts of the world [1, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. We found that B. dorsalis can be re-inoculated with bacterial isolates at the embryo stage and that the effects of such isolates on host development and susceptibility to pathogens can subsequently be evaluated.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics are often employed in studies to disrupt the gut microbiota of insects. In addition, antibiotics may have detrimental effects on host organisms, for instance the interference of the protein synthesis mechanisms of the host [48]. The dechorionation of embryos coupled with rearing on germ-free diets has been reported to be more effective in eliminating bacteria from insect eggs than the use of antibiotics [48]. For this reason, we adopted a dechorionation approach to generate axenic flies for mono-association experiments.

The absence of bacteria in the axenic lines was observed to significantly lengthen the period taken for embryos to hatch compared to B. dorsalis lines inoculated with individual bacterial isolates, as well as the Ut-control which had an intact microbiome. This suggests that the effect of bacterial isolates on hatching time may be combinatorial, or possibly there are isolates that have stronger effects but these were not isolated in our experiments. However, the mechanisms through which embryonic development and bacteria intersect are still unclear. In other insects, microbiomes have been associated with hatching duration for both host and parasite eggs [49, 50].

The shortest larval development period was recorded in flies with an intact microbiome as well as in the P. alcalifaciens line whereas the longest period was recorded in the E. cloacae fly line. In other insects, E. cloacae has been shown to stimulate the host’s immune responses which can protect the host from other pathogens or in some others it causes pathogenesis and mortality [51,52,53]. In B. dorsalis, this bacterium has been reported to increase fecundity but lower the longevity of adult flies [39]. Since this bacterium has frequently been detected as a member of the B. dorsalis gut microbiota, it may be that the host benefits from accommodating this bacterium, despite the decreased longevity because of its enhancement of reproductive capacity. In comparison, L. lactis has also been reported to prolong larval development of B. dorsalis when supplemented in diet of non-axenic flies [37]. In this study, L. lactis inoculated in B. dorsalis did not cause significant variation in duration of the larval stage relative to other isolates and control conditions.

The observed variations in development time of various stages of an insect host could be directly influenced by some dominant roles played by bacterial symbionts in the host’s physiology, immune homeostasis, detoxification, and in nutrient provisioning and utilization. Of these, proteomics evidence suggests that the most dominant role played by bacteria is amino acid synthesis, followed by protein digestion, energy metabolism, vitamin biosynthesis, lipid digestion, plant secondary metabolite degradation, and carbohydrate digestion [54]. Future studies could evaluate the intricate mechanisms of bacterial influence in the development of important pests such as B. dorsalis.

Minor but significant effects of bacterial isolates on puparia weight were recorded, however, no significant differences in puparia length and width measurements were recorded amongst all the inoculated B. dorsalis lines. It could be possible that these are not useful parameters for testing fitness variations in B. dorsalis. The lower puparia weight recorded in the Ut-control relative to majority of B. dorsalis lines with re-introduced bacteria supports a previous report which demonstrated that supplementing larval diets with certain gut bacteria results in a significant increase in puparia weight for B. dorsalis [37] as well as for the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann) (Diptera: Tephritidae) [55]. Increased pupal weight due to addition of probiotics has been associated with increased adult size and mating success of males [55]. Inclusion of K. oxytoca and P. alcalifaciens which promoted the highest pupal weight in this study as probiotics in rearing diets might therefore be useful in sterile insect technique (SIT) programs that capitalize on male mating success, since the high pupal weight gain in this study was indiscriminate of sex of the flies. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that K. oxytoca can repair the ecological fitness damage caused by irradiation of B. dorsalis, as well as improve food intake and elevate sugar and amino acid levels in the haemolymph of irradiated flies [45].

We recorded significant differences in survival of B. dorsalis flies after exposure to the entomopathogenic fungus, M. anisopliae. Notably, the B. dorsalis line inoculated with L. lactis exhibited poor survival relative to the axenic control and two other isolates. The L. lactis could therefore have some level of M. anisopliae-synergistic pathogenicity to B. dorsalis at adult stage resulting in poor survival of exposed flies. In other studies, L. lactis has been demonstrated to have pathogenic effects when supplemented in larval rearing diets of B. dorsalis, resulting in overall decreased survival of flies [37]. However, this effect might be strain specific, since no overt pathogenic effects such as decreased survival rates were recorded in the presence of L. lactis without M. anisopliae in our experiments. Under natural conditions, it is possible that L. lactis strains cause low but variable levels of pathogenicity to adult B. dorsalis. Also, B. dorsalis could have adaptive decoupling where immature stages mount a stronger response against L. lactis than adult stages. Such has been demonstrated in mosquitoes [56]. In addition, L. lactis has been described as a non-obligate pathogen capable of achieving high bacterial loads during infection yet result in low mortality in a Drosophila model [57]. This could relate to our finding that Lactococcus was dominant in wild flies from Embu and Nguruman, as well as with other studies that have detected this bacterium in B. dorsalis [1, 37, 38, 42, 43, 45, 58]. This indicates that L. lactis is ordinarily accommodated as a member of the B. dorsalis microbiota due to possible benefit to larvae (or adults) which balances out a fitness cost to adults. Alternatively, it is possible that L. lactis is a low virulence pathogen that is overall detrimental to B. dorsalis under natural conditions.

Transstadial persistence of various gut bacteria has been demonstrated in B. dorsalis [44, 59, 60]. Following the significant reduced survival and the relative improved survival between day 4 and 7 of adult flies exposed to M. anisopliae for the L. lactis and P. alcalifaciens inoculated B. dorsalis lines respectively, we evaluated the persistence of the re-introduced bacteria, at the adult stage. The re-introduced bacteria in axenic flies were found to persist from immature stages to adult stages of both the L. lactis and P. alcalifaciens inoculated B. dorsalis lines, with the latter line having a complete domination of gut tissues by the inoculated bacteria. Since immature stages of both B. dorsalis lines were reared in similar axenic conditions whereas adult flies were maintained under normal conditions, the presence of lesser quantities of other bacteria in the L. lactis line and not in the P. alcalifaciens line indicate a stronger competitive inhibitory effect of the latter isolate to proliferation of environmental microbes in the 2-day foraging window between eclosion and testing. The effects of supplementation of larval diets with such gut bacteria are therefore likely to persist across generations and populations since the transstadially transmitted bacteria could also be transmitted horizontally and through egg surface contamination as reported for some gut symbionts in B. dorsalis [61, 62].

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the role of gut bacteria in the development of immature stages of B. dorsalis as well as a synergistic effect between the gut bacterium, L. lactis and a commonly used biopesticide, M. anisopliae, in decreasing the survival of adult stages of this pest. These findings reveal some profound effects of certain bacterial isolates on the biology of B. dorsalis. This can inform probiotic selection and development for B. dorsalis rearing diets and also be applied in integrated pest management programs to increase the efficiency of entomopathogenic fungi.

Methods

16S rRNA sequencing

To assess the broader composition of gut microbiota associated with B. dorsalis populations in five mango growing regions in Kenya, high throughput sequencing of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was carried out for adult samples collected in 2016 and third stage larval samples collected in 2018, retrieved from Kent variety mangoes, with inclusion of a laboratory reared (icipe) colony for comparison. Infested mangoes were collected from farms in Embu (S 0° 28′ 56.6“ E 37° 34’ 55.5”), Muranga (S 0° 42′ 50.0“ E 37° 07’ 03.4”), Nguruman (S 1° 48′ 32″ E 36° 03′ 35″), Makueni (S 2° 21′ 18.9576″ E 38° 11′ 26.376″) and Kitui (S 01° 21′ E 38° 00′).

At each sampling, infested mangoes were washed in distilled water, dissected and placed on sterile sand in ventilated cages at 27 ± 2 °C and 70% humidity to allow third stage larvae to burrow and pupate in sand. Puparia were retrieved from sand through sieving and maintained in sterile petri dishes in ventilated Perspex cages until eclosion. A proportion of third instar larvae were directly retrieved from the fruit for gut dissection. Emerging 1 day old adult flies from respective sites were collected for gut dissections.

Guts were dissected in sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4·7H2O, and 1.8 mM KH2PO4 [pH 7.4]) after surface sterilization of the specimens. The selected larvae and adult flies were surface sterilized as described previously [63]. Dissected guts were homogenized using pestles in 1 ml microfuge tubes containing 300 μl PBS.

A total of five adult specimens per site sampled in 2016, and four larval specimens per site sampled in 2018 were randomly selected for DNA extraction. In addition, five adult flies and four larval specimens were included from the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe) fruit fly laboratory colony. The sampled colony was derived from infested mango collected from different farms across Kenya and maintained for more than 40 generations with frequent wild infusions in the laboratory at 27 °C and 60% relative humidity. Adult flies were fed on a diet consisting of 3 parts sugar and 1-part enzymatic yeast hydrolysate ultrapure (USB Corporation, Cleveland, Ohio, USA), and water on pumice granules. For each generation, fresh mango domes were used as oviposition receptacles, from which embryos were washed in distilled water before inoculation on larval rearing diets [64]. Same age and generation of laboratory reared flies were used for this study.

DNA extraction and high throughput sequencing were carried out as previously described [63]. Larval DNA was sequenced at the Centre for Integrated Genomics, University of Lausanne, Switzerland and adult DNA at the Macrogen Europe Laboratory, the Netherlands. Adult and larval sequence sets were therefore analyzed separately.

16S rRNA gene sequence analysis

Sequence reads were quality checked and pre-processed in QIIME2 [65] as described previously [63]. A total of 638,815 sequence reads from adult specimens and 56,425 from larval specimens that were retained after removal of spurious reads and all reads shorter than 240 and 272 nucleotides in length respectively, were subjected to further analysis. These sequences clustered into 235 OTUs (adult) and 402 OTUs (larval). Of these, 50 OTUs (adult) and 94 OTUs (larval) survived low count and interquartile range-based variance filtering to eliminate OTUs that could arise from sequencing errors and contamination. Taxonomic assignment, OTU variance filtering and beta diversity measures were carried out as previously described [63]. Differential abundance of bacterial genera was evaluated using the differential gene expression analysis based on the negative binomial distribution (DESeq 2) tool [66].

Bacterial isolation

Cultivable bacteria were isolated from gut homogenates of both larvae and adult flies collected during 2018 from the aforementioned sites in Kenya. Larvae and adults were retrieved from infested mangoes and their guts dissected and homogenized as described above. An aliquot of 5 μl of the fourth serial dilution of each homogenate was inoculated under aerobic conditions on brain heart infusion (BHI) solid media using the spread plate technique [67] and incubated at 37 °C for 14 h. Representative colony forming units (cfu) were selected based on morphology and clonally propagated up to four times to ensure purity on BHI agar plates.

Bacterial isolates identification

Pure isolates were sub-cultured in BHI broth and incubated at 37 °C for 16 h on a shaking platform at 300 rpm. Bacterial cells were harvested from media then washed thrice in PBS by centrifugation at 10000 rpm for 10 min at 10 °C, each time discarding the supernatant.

DNA extraction from bacterial cells and PCR amplification were carried out as described previously [63] with slight variations in the primers used i.e. the 28F (5′-GAGTTTGATCNTGGCTCAG-3′) and 519R (5′-GTNTTACNGCGGCKGCTG-3′) primer pair, as well in the cycling conditions, where, following the initial denaturation, 35 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 40 s at 54 °C and 1 min at 72 °C were run, followed by the final elongation step. Direct Sanger sequencing in both forward and reverse directions was done for all amplified samples. Sequence alignments were performed using Clustal W in Geneious 8.1.9 software [68]. Homology searches using BLAST against the 16S ribosomal RNA sequence database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) were done to infer identity and similarity of isolates to subject sequences in the database.

Generation of axenic lines

Bactrocera dorsalis embryos were collected from gravid females from the icipe B. dorsalis laboratory reared colony using perforated mango domes. Embryos were surface sterilized in 70% ethanol for 5 min, then dechorionated in a 7% v/v sodium hypochlorite solution for 3 min in a fine mesh (Nitex Nylon100 μm) basket. Dechorionated embryos were rinsed three times in distilled water for 5 min each then flooded with absolute ethanol. Sterile materials were used in subsequent procedures in a sterile laminar flow hood. Using a fine camel hair brush, embryos from the bottom of the basket were transferred and spread out on 2 cm X 2 cm X 4 mm sponge cloth immersed in larval rearing diet [64] in flat base 30 mm X 100 mm cylindrical test tubes. Approximately 100 embryos were placed in each tube. Axenic control lines were derived at this step by plugging cotton wool up to 3 cm from the top of the tube.

Generation of mono-association lines

An inoculum 50 μl of 1 X 104 cfu/ml of each isolate was introduced in triplicate per experiment directly onto the embryos before plugging the tubes with cotton wool.

Rearing and quality check of fly lines

All tubes were maintained at 27 °C and 70% humidity. A control group with an intact microbiome (whose embryos were not dechorionated) was included in triplicate in each experiment. The immature stages of all B. dorsalis lines were reared in axenic conditions.

To quality check axenic lines, random third stage larvae were retrieved from axenic control tubes per experiment and homogenized in 50 μl PBS. Five μl of this homogenate was plated on nutrient agar plates and incubated at 37 °C and checked for bacterial growth after 15 h. A volume of 200 μl of sterile larval rearing diet was added to each tube every 24 h after hatching.

No bacterial growth from third instar larvae was recorded on enriched media plates during quality check of axenic lines, inferring a strong elimination effect using this approach.

Mature third-stage larvae crawled upward and burrowed into the cotton wool plug to pupate. The time taken to the observation of at least 10 first instar larvae as well as to the observation of puparia on the cotton wool plug were recorded for each tube. Measurements of 1-day old puparia weight, dorsal to ventral length as well as width of the sixth segment were also recorded. Weights were recorded in triplicates of 20 puparia each from every fly line, whereas length and width measurements were recorded from 20 puparia per fly line. Length measurements were carried out under a Leica LAS EZ4D stereomicroscope (Leica Ltd., Switzerland). Cotton wool plugs with puparia were submerged in autoclaved distilled water at room temperature and carefully pulled apart to free puparia. The retrieved puparia were dried on sterile paper towel and maintained on sterile Petri dishes placed in sterilized ventilated Perspex cages until eclosion at 27 °C and 70% humidity. Eclosed adult flies were maintained under normal conditions. All data for development and puparia measurements were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk’s test. Non-normal distributions were recorded in the embryo duration (W = 0.84, p < 0.001), larval duration (W = 0.92, p < 0.001), puparia length (W = 0.93, p < 0.001), puparia width (W = 0.96, p < 0.001) and puparia weight (W = 0.87, p < 0.001) datasets. All datasets conformed to homogeneity of variance as determined using the Levene’s test: embryo duration (F(6, 56) = 0.50, p = 0.81), larval duration (F(6, 56) = 1.24, p = 0.30), puparia length (F(6, 133) = 0.85, p = 0.54), puparia width (F(6, 133) = 1.31, p = 0.26) and puparia weight (F(6, 56) = 1.34, p = 0.25). Statistical significance in the datasets was therefore evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons post hoc test. All analyses were conducted in the R statistical software [69]. In addition, adult flies emerging from all mono associated lines were monitored for fitness for a period of 12 days post eclosion. No mortality was recorded in any of the B. dorsalis lines during this period.

Exposure to Metarhizium anisopliae

Dry conidia of M. anisopliae ICIPE69 were obtained from icipe’s Arthropod Pathology Unit Germplasm. Triplicates in groups of 20 newly emerged adult flies from each fly line were each exposed to 0.3 g of dry spores of the M. anisopliae ICIPE69 for 1 min in a contamination device made from a 50 ml falcon tube lined with velvet. Exposed flies were released in 10 cm × 10 cm × 10 cm ventilated cages and maintained on adult B. dorsalis rearing diet [70] and sterile water saturated on cotton wool at 27 °C and 70% humidity. A control set derived from unexposed flies was included in each treatment. All flies in this set (unexposed to fungus) in all B. dorsalis lines survived the duration of the experiment. The survival rates of B. dorsalis from the different fly lines were monitored daily after exposure to the M. anisopliae isolate. Pairwise comparisons of survival between all the fly lines and controls was evaluated using the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test. Survival curves for adult flies exposed to ICIPE69 were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method in the Graph Pad Prism software, version 7.00 for Windows [71].

Fly line microbiota

Gut tissues from a pool of five 2-day post eclosion adult flies per line from the L. lactis and the P. alcalifaciens inoculated B. dorsalis lines were processed as described above for high throughput sequencing, targeting the v3-v4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene, and similarly analyzed in QIIME2–2018.11.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject: PRJNA545161 and in the GenBank, accessions MK968291-MK968302.

Abbreviations

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffered saline

- OTU:

-

Operational taxonomic unit

- BHI:

-

Brain heart infusion

- cfu:

-

Colony forming unit

- rpm:

-

Revolutions per minute

- SIT:

-

Sterile insect technique

- icipe :

-

International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology

References

Shi Z, Wang L, Zhang H. Low diversity bacterial community and the trapping activity of metabolites from cultivable bacteria species in the female reproductive system of the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis Hendel (Diptera: Tephritidae). Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:6266–78.

Wan X, Nardi F, Zhang B, Liu Y. The oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis, in China: origin and gradual inland range expansion associated with population growth. PLoS One. 2011;6:1–10.

De Villiers M, Hattingh V, Kriticos DJ, Brunel S, Vayssières J, Sinzogan A, et al. The potential distribution of Bactrocera dorsalis: considering phenology and irrigation patterns. Bull Entomol Res. 2016;106:19–33.

Manrakhan A, Venter JH, Hattingh V. The progressive invasion of Bactrocera dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae) in South Africa. Biol Invasions. 2015;17:2803–9.

Lux SA, Copeland RS, White IM, Manrakhan A, Billah MK. A new invasive fruit fly species from the Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) group detected in East Africa. Int J Trop Insect Sci. 2003;23:355–61. https://doi.org/10.1017/S174275840001242X.

Wan X, Liu Y, Zhang B. Invasion history of the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis, in the Pacific-Asia region: two main invasion routes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36176.

Khamis FM, Karam N, Ekesi S, De Meyer M, Bonomi A, Gomulski LM, et al. Uncovering the tracks of a recent and rapid invasion: the case of the fruit fly pest Bactrocera invadens (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Africa. Mol Ecol. 2009;18:4798–810.

Stephens AEA, Kriticos DJ, Leriche A. The current and future potential geographical distribution of the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae). Bull Entomol Res. 2007;97:369–78.

EPPO. Global Database. Bactrocera dorsalis (DACUDO) distribution details in United States of America; 2019. https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/DACUDO/distribution/US/. Accessed 04 July 2020.

Ekesi S, Mohamed SA, de Meyer M. Fruit Fly Research and Development in Africa - Towards a Sustainable Management Strategy to Improve Horticulture. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43226-7.

Goergen G, Vayssières J-F, Gnanvossou D, Tindo M. Bactrocera invadens (Diptera: Tephritidae), a new invasive fruit fly pest for the Afrotropical region: host plant range and distribution in west and Central Africa. Environ Entomol. 2011;40:844–54. https://doi.org/10.1603/EN11017.

EPPO. Global Database. Bactrocera dorsalis (DACUDO) categorization; 2019. https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/DACUDO/categorization/. Accessed 04 July 2020.

Dohino T, Hallman GJ, Grout TG, Clarke AR, Follett PA, Cugala DR, et al. Phytosanitary treatments against Bactrocera dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae): current situation and future prospects. J Econ Entomol. 2017;110:67–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/tow247.

Klepzig KD, Adams AS, Handelsman J. Symbioses: a key driver of insect physiological processes, ecological interactions, evolutionary diversification, and impacts on humans. Environ Entomol. 2009;38:67–77.

Kafil M, Bandani AR, Kaltenpoth M, Goldansaz SH, Alavi SM. Role of symbiotic bacteria in the growth and development of the Sunn pest, Eurygaster integriceps. J Insect Sci. 2013;13:99.

De Vries EJ, Jacobs G, Sabelis MW, Menken SBJ, Breeuwer JAJ. Diet-dependent effects of gut bacteria on their insect host: the symbiosis of Erwinia sp. and western flower thrips. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2004;271:2171–8.

Visôtto LE, Oliveira MGA, Guedes RNC, Ribon AOB, Good-God PIV. Contribution of gut bacteria to digestion and development of the velvetbean caterpillar, Anticarsia gemmatalis. J Insect Physiol. 2009;55:185–91.

Fridmann-Sirkis Y, Stern S, Elgart M, Galili M, Zeisel A, Shental N, et al. Delayed development induced by toxicity to the host can be inherited by a bacterial-dependent, transgenerational effect. Front Genet. 2014;5:27.

Kaltenpoth M, Winter SA, Kleinhammer A. Localization and transmission route of Coriobacterium glomerans, the endosymbiont of pyrrhocorid bugs. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2009;69:373–83.

Prado SS, Almeida RPP. Role of symbiotic gut bacteria in the development of Acrosternum hilare and Murgantia histrionica. Entomol Exp Appl. 2009;132:21–9.

Sannino DR, Dobson AJ, Edwards K, Angert ER, Buchon N. The Drosophila melanogaster gut microbiota provisions thiamine to its host. MBio. 2018;9:e00155–18.

Su W, Liu J, Bai P, Ma B, Liu W. Pathogenic fungi-induced susceptibility is mitigated by mutual Lactobacillus plantarum in the Drosophila melanogaster model. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19:302.

Panteleev DY, Goryacheva II, Andrianov BV, Reznik NL, Lazebny OE, Kulikov AM. The endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia enhances the nonspecific resistance to insect pathogens and alters behavior of Drosophila melanogaster. Russ J Genet. 2007;43:1066–9.

Currie CR, Scottt JA, Summerbell RC, Malloch D. Fungus-growing ants use antibiotic-producing bacteria to control garden parasites. Lett to Nat. 1999;398:701–4.

Kaltenpoth M, Göttler W, Herzner G, Strohm E. Symbiotic bacteria protect wasp larvae from fungal infestation. Curr Biol. 2005;15:475–9.

Scarborough CL, Ferrrari J, Godfray HCJ. Aphid protected from pathogen by endosymbiont. Science. 2005;310:1781. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1120180.

Lukasik P, Guo H, Van Asch M, Ferrari J, Godfray HCJ. Protection against a fungal pathogen conferred by the aphid facultative endosymbionts Rickettsia and Spiroplasma is expressed in multiple host genotypes and species and is not influenced by co-infection with another symbiont. J Evol Biol. 2013;26:2654–61.

Ferrari J, Darby AC, Daniell TJ, Godfray HCJ, Douglas AE. Linking the bacterial community in pea aphids with host-plant use and natural enemy resistance. Ecol Entomol. 2004;29:60–5.

Scott JJ, Oh D-C, Yuceer MC, Klepzig KD, Clardy J, Currie CR. Bacterial protection of beetle-fungus mutualism. Science. 2008;322:63. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1160423.

Gil-Turnes MS, Fenical W. Embryos of Homarus americanus are protected by epibiotic bacteria. Biol Bull. 1992;182:105–8.

Gil-Turnes MS, Hay ME, Fenical W. Symbiotic marine bacteria chemically defend crustacean embryos from a pathogenic fungus. Science. 1989;246:116–8.

Ekesi S, Mohamed SA. Mass rearing and quality control parameters for tephritid fruit flies of economic importance in Africa. In: Akyar I, editor. Wide Spectra of Quality Control. Rijeka: InTech; 2011. p. 387–410. https://doi.org/10.5772/21330.

Ekesi S, Dimbi S, Maniania NK. The role of entomopathogenic fungi in the integrated management of tephritid fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) with emphasis on species occurring in Africa. In: Ekesi S, Maniania N, editors. Use of Entomopathogenic Fungi in Biological Pest Management. Kerala: Research SignPost; 2007. p. 239–74.

Muriithi BW, Affognon HD, Diiro GM, Kingori SW, Tanga CM, Nderitu PW, et al. Impact assessment of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategy for suppression of mango-infesting fruit flies in Kenya. Crop Prot. 2016;81:20–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2015.11.014.

Maniania JNK, Ekesi S. Development and application of mycoinsecticides for the management of fruit flies in Africa. In: Ekesi S, Mohamed SA, de Meyer M, editors. Fruit Fly Research and Development in Africa - Towards a Sustainable Management Strategy to Improve Horticulture. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 307–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43226-7_15.

Vargas RI, Piñero JC, Leblanc L. An overview of pest species of Bactrocera fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) and the integration of biopesticides with other biological approaches for their management with a focus on the pacific region. Insects. 2015;6:297–318.

Khaeso K, Andongma AA, Akami M. Assessing the effects of gut bacteria manipulation on the development of the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis (Diptera ; Tephritidae). Symbiosis. 2017;74:97–105.

Yong H-S, Song S-L, Chua K-O, Lim P-E. Microbiota associated with Bactrocera carambolae and B. dorsalis (Insecta: Tephritidae) revealed by next-generation sequencing of 16S rRNA gene. Meta Gene. 2017;11:189–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mgene.2016.10.009.

Akami M, Andongma AA, Zhengzhong C, Nan J, Khaeso K, Jurkevitch E, et al. Intestinal bacteria modulate the foraging behavior of the oriental fruit fly Bactrocera dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae). PLoS One. 2019;14:e0210109.

Wang H, Jin L, Peng T, Zhang H, Chen Q, Hua Y. Identification of cultivable bacteria in the intestinal tract of Bactrocera dorsalis from three different populations and determination of their attractive potential. Pest Manag Sci. 2013;70:80–7.

Gujjar NR, Govindan S, Verghese A, Subramanian S, More R. Diversity of the cultivable gut bacterial communities associated with the fruit flies Bactrocera dorsalis and Bactrocera cucurbitae (Diptera: Tephritidae). Phytoparasitica. 2017;45:450–60.

Wang H, Jin L, Zhang H. Comparison of the diversity of the bacterial communities in the intestinal tract of adult Bactrocera dorsalis from three different populations. J Appl Microbiol. 2011;110:1390–401.

Cheng D, Guo Z, Riegler M, Xi Z, Liang G, Xu Y. Gut symbiont enhances insecticide resistance in a significant pest, the oriental fruit fly Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel). Microbiome. 2017;5:1–12.

Zhao X, Zhang X, Chen Z, Wang Z, Lu Y, Cheng D. The divergence in bacterial components associated with Bactrocera dorsalis across developmental stages. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:114.

Cai Z, Yao Z, Li Y, Xi Z, Bourtzis K, Zhao Z, et al. Intestinal probiotics restore the ecological fitness decline of Bactrocera dorsalis by irradiation. Evol Appl. 2018;13:1946–63.

Damodaram K, Ayyasamy A, Kempraj V. Commensal bacteria aid mate-selection in the fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis. Microb Ecol. 2016;72:725–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-016-0819-4.

Pietri JE, Liang D. The links between insect symbionts and insecticide resistance: causal relationships and physiological tradeoffs. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 2018;111:92–7.

Ridley EV, Wong ACN, Douglas E. Microbe-dependent and nonspecific effects of procedures to eliminate the resident microbiota from Drosophila melanogaster. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:3209–14.

Ponnusamy L, Böröczky K, Wesson DM, Schal C, Apperson CS. Bacteria stimulate hatching of yellow fever mosquito eggs. PLoS One. 2011;6:1–10.

Fredensborg BL, Kálvalíð IF, Johannesen TB, Stensvold CR, Nielsen HV, Kapel CMO. Parasites modulate the gut-microbiome in insects: a proof-of-concept study. PLoS One. 2020;15:1–18.

Abassi R, Akhlaghi M, Oshaghi MA, Akhavan AA, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR, Bakhtiary R, et al. Dynamics and fitness cost of genetically engineered Entrobacter cloacae expressing defensin for paratransgenesis in Phlebotomus papatasi. J Bacteriol Parasitol. 2018;10:349. https://doi.org/10.35248/2155-9597.1000349.

Bischoff V, Vignal C, Duvic B, Boneca IG, Hoffmann JA, Royet J. Downregulation of the Drosophila immune response by peptidoglycan-recognition proteins SC1 and SC2. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e14.

Thakur A, Dhammi P, Saini HS, Kaur S. Pathogenicity of bacteria isolated from gut of Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and fitness costs of insect associated with consumption of bacteria. J Invertebr Pathol. 2015;127:38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2015.02.007.

Jing TZ, Qi FH, Wang ZY. Most dominant roles of insect gut bacteria: digestion, detoxification, or essential nutrient provision? Microbiome. 2020;8:38.

Hamden H, Guerfali MMS, Fadhl S, Saidi M, Chevrier C. Fitness improvement of mass-reared sterile males of Ceratitis capitata (Vienna 8 strain) (Diptera: Tephritidae) after gut enrichment with probiotics. J Econ Entomol. 2013;106:641–7.

League GP, Estévez-Lao TY, Yan Y, Garcia-Lopez VA, Hillyer JF. Anopheles gambiae larvae mount stronger immune responses against bacterial infection than adults: evidence of adaptive decoupling in mosquitoes. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:367.

Kutzer MAM, Armitage SAO. The effect of diet and time after bacterial infection on fecundity, resistance, and tolerance in Drosophila melanogaster. Ecol Evol. 2016;6:4229–42.

Bai Z, Liu L, Noman MS, Zeng L, Luo M, Li Z. The influence of antibiotics on gut bacteria diversity associated with laboratory-reared Bactrocera dorsalis. Bull Entomol Res. 2019;109:500–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485318000834.

Andongma AA, Wan L, Dong Y-C, Li P, Desneux N, White JA, et al. Pyrosequencing reveals a shift in symbiotic bacteria populations across life stages of Bactrocera dorsalis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9470. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09470.

Khan M, Seheli K, Bari MA, Sultana N, Khan SA, Sultana KF, et al. Potential of a fly gut microbiota incorporated gel-based larval diet for rearing Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel). BMC Biotechnol. 2019;19 Suppl 2:94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12896-019-0580-0.

Guo Z, Lu Y, Yang F, Zeng L, Liang G, Xu Y. Transmission modes of a pesticide-degrading symbiont of the oriental fruit fly Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel). Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101:8543–56.

Badii KB, Billah MK, Nyarko G. Review of the pest status, economic impact and management of fruit-infesting flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Africa. African J Agric Res. 2015;10:1488–98.

Gichuhi J, Sevgan S, Khamis F, Van den Berg J, du Plessis H, Ekesi S, et al. Diversity of fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda and their gut bacterial community in Kenya. PeerJ. 2020;8:e8701. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.8701.

Chang CL. Fruit fly liquid larval diet technology transfer and update. J Appl Entomol. 2009;133:164–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0418.2008.01345.x.

Boylen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich NA, Abnet C, Ghalith GAA, et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;37:852–7.

Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550.

Buck JD, Cleverdon RC. The spread plate as a method for the enumeration of marine bacteria. Limnol Oceanogr. 1954;5:78–80.

Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, et al. Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–9.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing; 2014. http://www.r-project.org/. Accessed 19 Nov 2017.

Ekesi S, Nderitu PW, Rwomushana I. Field infestation, life history and demographic parameters of the fruit fly Bactrocera invadens (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Africa. Bull Entomol Res. 2006;96:379–86.

GraphPad Prism version 7.00 for Windows, GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA. http://www.graphpad.com. Accessed 11 Sep 2017.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the icipe fruit fly team, icipe APU laboratory, icipe EID-laboratory, and icipe Bee Health laboratory for facilitation of this work.

Funding

Financial support for this research came from the following organizations and agencies: European Union Funded Integrated Biological Control Applied Research Program (IBCARP)-Fruit Fly Component; the Wellcome trust [107372]; UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO); the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida); the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC); the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia; and the Government of the Republic of Kenya. Financial assistance for sequencing at the Center for Integrated Genomics, Lausanne, was provided by the Global Health Institute of the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.G. carried out the experiments, data analysis and authored the manuscript. F.K. J.V.B. J.K.H. S.M. and S.E. designed, conceptualized and supervised the study. S.E. acquired funding for the study. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 Supplementary Fig. 1.

Relative abundance of bacterial genera in adult B. dorsalis specimens sampled from different sites in Kenya.

Additional file 2 Supplementary Fig. 2.

Relative abundance of bacterial genera in larvae specimens of B. dorsalis collected from different sites in Kenya.

Additional file 3 Supplementary Fig. 3.

Differential abundance of A) Enterobacter B) Klebsiella C) Serratia in adult specimens, and D) Lactobacillus in larvae of B. dorsalis sampled from different sites in Kenya.

Additional file 4 Supplementary Fig. 4.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) ordination based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrices (A and C) and Unweighted UniFrac distance matrices (B and D) showing significantly different microbial compositions among different sites. Plots A and B show compositions in adult specimens while C and D show compositions in larval specimens of B. dorsalis. Significance values are indicated in each plot. Individual specimens are represented as dots colored according to sampling site.

Additional file 5 Supplementary Table 1.

Description of identified bacterial isolates and their GenBank accession numbers.

Additional file 6 Supplementary Table 2:

Pairwise comparison of survival rates between bacterial-inoculated B. dorsalis lines, post exposure to entomopathogenic fungus.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gichuhi, J., Khamis, F., Van den Berg, J. et al. Influence of inoculated gut bacteria on the development of Bactrocera dorsalis and on its susceptibility to the entomopathogenic fungus, Metarhizium anisopliae. BMC Microbiol 20, 321 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-020-02015-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-020-02015-y