Abstract

Background

The Oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) (Diptera: Tephritidae), is an important polyphagous pest of horticultural produce. The sterile insect technique (SIT) is a proven control method against many insect pests, including fruit flies, under area-wide pest management programs. High quality mass-rearing process and the cost-effective production of sterile target species are important for SIT. Irradiation is reported to cause severe damage to the symbiotic community structure in the mid gut of fruit fly species, impairing SIT success. However, studies have found that target-specific manipulation of insect gut bacteria can positively impact the overall fitness of SIT-specific insects.

Results

Twelve bacterial genera were isolated and identified from B. dorsalis eggs, third instars larval gut and adults gut. The bacterial genera were Acinetobacter, Alcaligenes, Citrobacter, Pseudomonas, Proteus, and Stenotrophomonas, belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family. Larval diet enrichment with the selected bacterial isolate, Proteus sp. was found to improve adult emergence, percentage of male, and survival under stress. However, no significant changes were recorded in B. dorsalis egg hatching, pupal yield, pupal weight, duration of the larval stage, or flight ability.

Conclusions

These findings support the hypothesis that gut bacterial isolates can be used in conjunction with SIT. The newly developed gel-based larval diet incorporated with Proteus sp. isolates can be used for large-scale mass rearing of B. dorsalis in the SIT program.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The insect gut contains an array of microorganisms that influence its fitness [1, 2]. Such microbial partners contribute to host metabolism [3, 4], facilitate nutrient uptake [5], prolong host lifespan [6], strengthen mating competitiveness [7], defend against natural enemies [8], and help detoxify diets [9]. Several gut bacteria have shown to act as lures [10] which may potentially be used as biocontrol agents [11, 12]. Without symbiotic bacteria, insects are reported to have reduced growth rates and higher mortality [2, 13].

Abundant symbiotic communities in the digestive tract have been reported in fruit flies including Ceratitis capitata (Widemann) [6, 7], Bactrocera oleae (Gemlin) [4, 14, 15], Bactrocera tau (Walker) [16, 17], Zeugodacus (Bactrocera) cucurbitae (Coq.) [18], Bactrocera carambolae (Drew &Hancock) [19], Bactrocera cacuminata (Hering) Bactrocera tryoni (Froggatt) [20], the apple maggot fly, Rhagoletis pomonella (Walsh) [9], and the Mexican fruit fly, Anastrepha ludens (Loew) [21]. To characterize the gut symbiotic community structure of Tephritidae species, both culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches have been used, particularly in the med fly, which revealed a symbiotic bacterial community of different Enterobacteriaceae species from the genera Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Providencia, Pectobacterium, Pantoea, Morganella and Citrobacter [4, 22,23,24,25].

The bacterial community associated with B. dorsalis development is also well-studied [11, 12, 26,27,28,29]. Based on 454 pyrosequencing, the gut of different developmental stages in B. dorsalis harbors gut bacteria representing six phyla, where Proteobacteria dominates in the immature stages and Firmicutes (Enterococcaceae) dominates in the adult stages [30]. Using16S rRNA-based polymerase chain reaction-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (PCR-DGGE), the female B. dorsalis reproductive system revealed the presence of Enterobacter sakazakii, Klebsiella oxytoca, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Raoultella terrigena and Enterobacter amnigenus [11].

Explorations on other fruit fly-associated bacterial communities also revealed an almost universal presence of species-specific Enterobacteriaceae, notably species of Enterobacter, Klebsiella, and Pectobacterium [26, 31,32,33]. Strain abundance and diversity varied due to different ontogenetic stages [7, 22, 25]; however, the symbiotic community for mass rearing and genetic sexing strains (GSSs), such as the ‘Vienna 7’ strain, was reportedly reduced to only Enterobacter sp. [34].

The applied value of Enterobacter spp. in rearing C. capitata for the sterile insect technique (SIT) and other pest management strategies has been demonstrated in different studies [7, 13, 35, 36]. Several gut bacteria spp. (K. pneumoniae, Citrobacter freundii and Enterobacter cloacae) have shown to be attractive lures for Tephritidae, including B. dorsalis and Bactrocera zonata (Saunders) [10,11,12]. The gut bacterium, C. freundii of B. dorsalis was reported to enhance the fruit flies’ resistance to trichlorphon [37].

Encouraging results have also been reported on the use of different bacteria as probiotics (i.e., as larval or adult diet supplements) [7, 24, 36] to resolve the quality problems that may derive from disrupting the gut symbiota during mass rearing and/or irradiation [38, 39]. Supplementing Enterobacter sp. in the larval diet was reported to significantly enhance fitness and sexual performance of the laboratory-raised GSS C. capitata, ‘Vienna 8’ [40] and GSS Z. cucurbitae [18]. Similarly, using the med fly adult gut bacterial isolate, K. oxytoca as an adult diet probiotic increased the mating competitiveness of sterile mass-reared C. capitata males and also reduced the receptivity of wild-type females after mating with males fed the probiotic diet [7, 36].

B. dorsalis is a polyphagous pest species to 117 hosts, from 76 genera and 37 families in Asia [41]. The fly species causes significant economic damage to many fruits and horticultural products. SIT has been practiced as an alternative and environmentally friendly control method for B. dorsalis in different countries [42]. The successful use of SIT to control these fruit flies relies on mass-rearing facilities for flies with many fit, sterile adult males [39] to release irradiation-induced sterile flies in the field, targeting the B. dorsalis wild populations [13]. These releases lead to sterile crosses and subsequently suppress the population. However, the fruit flies targeted for SIT exhibit inferior field performance, mating competitiveness, and other qualitative parameters compared with wild fruit flies. Therefore, SIT’s success may be impaired by, artificial selection driven by mass-rearing conditions, and irradiation [7, 43].

Research conducted on B. dorsalis area-wide management largely focused on monitoring and control with lures [44], mating compatibility [45], spatial distribution [46], and genetics [47]. Recently, research was conducted to isolate and characterize the B. dorsalis gut bacterial community [11, 12, 26,27,28,29], but little is known regarding probiotic applications in B. dorsalis mass rearing and fitness parameters to support SIT. The present study aimed to: (1) isolate and characterize bacterial species using culture-based methods and (2) use one selected gut bacteria sp. (Proteus sp.) as a dietary supplement in gel-based larval diets to assess its effects on the quality parameters of mass-reared B. dorsalis.

Methods

Oriental fruit flies were obtained from a colony maintained for 60 generations on a liquid artificial larval diet [48] in the laboratory of Insect Biotechnology Division (IBD), Institute of Food and Radiation Biology (IFRB), Atomic Energy Research Establishment (AERE), Savar, Dhaka. Approximately 5000 adult flies were maintained in steel-framed cages (76.2 cm × 66 cm × 76.2 cm, H × L × W) covered with wire nets. Adults were fed protein-based diets in both liquid and dry form: (i) baking yeast: sugar: water at a 1:3:4 ratio and (ii) casein: yeast extract: sugar at a 1:1:2 ratio. Water was supplied in a conical flask socked with a cotton ball. The temperature, relative humidity and light conditions in the rearing room were maintained at 27 ± 1 °C, 65 ± 5% and a 14:10 light(L):dark(D)cycle.

Gut bacteria isolation

Fresh eggs (6 h old, 10–15 in number), three popping (third instar) larvae, and three 15-day-old female B. dorsalis (reared on artificial liquid larval diet) were collected from a stock laboratory culture of the IBD. Eggs and larvae were rinsed with sterile distilled water and PBS buffer. Surface-sterilized larvae were individually dissected aseptically under a microscope. The alimentary tract was carefully removed and the mid-gut was separated with forceps and removed for analysis. Adult flies were killed by freezing at − 20 °C for 4 min. They were then surface-sterilized with 70% ethanol for 1 min, 0.5% sodium hypochloride for 1 min, washed twice in sterile distilled water and dissected to remove the gut [20].

Eggs and each gut from the B. dorsalis larvae and adults were placed in a sterile 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube and washed again with sterile distilled water. All samples were homogenized separately with a sterile inoculation loop. Twenty to thirty micro liters per sample were then inoculated onto MacConkey and blood agar plates. The samples were also enriched in selenite broth. The MacConkey agar and selenite broth were aerobically incubated at 35 °C. Blood agar plates were incubated in a CO2 incubator at 35 °C for 24–48 h. Additional culturing was performed in BacT Alert blood culture bottles. Samples were then subcultured onto MacConkey and blood agar media and the plates were incubated as described above. All isolated colonies were sub cultured for pure growth. Bacterial isolates were initially Gram-stained to detect Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria along with morphology. Gram-negative rods were further identified by biochemical tests using both the conventional and Analytical Profile Index (API) 20E and 20NE (BioMerieuxsa 62,980, Marcy-1′Etoile, France) to the species level. Gram-positive cocci were identified using catalase and other related biochemical tests such as the coagulase test and later confirmed by API Strep and API Staph. ID profiles were rated from good to excellent, based on API codes (https://apiweb.biomerieux.ccom/servlet/Authenticate?action=prepare Login).

Bacterial 16S rRNA gene amplification

Gut bacterial DNA was extracted with the ATP™ Genomic DNA Mini Kit (ATP Biotech, Inc., USA). The amount of DNA among per μl samples were measured by using Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific, USA). The 10 μl extracted DNA were amplified with 0.25 μl GoTaq® DNA polymerase (5u/μl), 10 μl 5× GoTaq® PCR flexi-buffer, 1 μl PCR nucleotide mix (10 mM each), 2 mM MgCl2, 1 μl (5–50 pmol) of each upstream and downstream primers and 25 μl nuclease free water in total volume of 50 μl reaction mixture. The PCR conditions were as follows: 35 cycles initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 94 °C for 45 s, then annealing at 50 °C for 1 min, and an extension at 72 °C for 1 min 30 s. The amplification products (3 μl per sample) were assessed on a 1% agarose 1x Tris-acetate EDTA (TAE) gel. The detected target bands were ca. 450 bp; a negative control reaction without template DNA was used to assess the samples for contamination. The 16S rRNA gene of the representative ESBL isolates belonging to each morphological group was amplified using primers 27F and 1492R. The purified products were further used for sequencing and phylogenetic analysis. Full length sequences (1465 bp) were assembled into the SeqMan Genome Assembler (DNAstar, USA) and compared to the GenBank database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank) by means of the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) to identify close phylogenetic relatives. Five bacterial 16S rRNA partial gene sequences were isolated and deposited into GenBank (MF927674, MF927675, MF927676, MF927677 and MF927678). Multiple sequence alignment of the retrieved reference sequences from NCBI was performed using ClustalW and the evolutionary history was inferred by using the maximum likelihood method based on the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano model [49]. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA6 [50].

Exploitation of Proteus sp. as a dietary supplement in the gel-based larval diet

Once the identity of the Proteus sp. (Proteus mirabilis) was established by 16S rRNA gene sequencing, we selected the bacterial isolate as a probiotic dietary supplement. This isolate was derived from the gut of the B. dorsalis third instar larvae. Both autoclaved and live bacteria were used at the same concentrations. No bacteria were added to the control diet. To date there are no reports on using Proteus spp. as a probiotic on Bactrocera flies. Proteus spp. is reported to tolerate and use pollutants, promote plant growth and have potential for use in bioremediation and environmental protection [51].

Diet formulation, preparation and delivery

The gel-based larval diet for B. dorsalis was prepared by adding 0.5 g agar (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in 150 ml of liquid diet as per the modified method of Khan et al. [48]. Diet components included sugar (8.96%) (Bangladesh Sugar and Food Industry Ltd., Dhaka), soy protein (7.51%) (Nature’s Bounty, Inc., USA), sterilized wholesale soy bran (3.86%) (fine powder), baking yeast (3.77% (Fermipan red, Langa Fermentation Company Ltd., Vietnam), citric acid (1.76%) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), sodium benzoate (0.29%), (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), and tap water (73.85%). Initial pH for these diets was between 3.5 and 4.

Diets were prepared by weighing all ingredients and mixing them in a blender with half the water until the ingredients were fully homogenous. The agar was then mixed with the rest of the water and heated for 4 min in a microwave to boiling. After heating, the agar was added to the ingredients in the blender and mixed again until homogenous. Four-hundred-fifty ml of the gel diet were then poured into a glass beaker (500 ml) and left to cool at room temperature. Six-ml (3.8 × 10− 6 CFU/ml) suspensions of Proteus sp. was mixed in with the gel diet homogeneously using a magnetic stirrer and poured into the rearing tray (40 cm long × 28 cm wide × 2.54 cm deep). A small strip of wet sponge cloth (2.7 cm, Kalle USA, Inc., Flemington, NJ, USA) was placed across the middle of the gel diet, and 1.5 ml of the eggs were seeded onto the sponge using a 5-ml plastic dropper. Larval diet trays were covered with clear plastic lids until larvae began popping and began to exit the diet to pupate. The lids were then removed, and the rearing trays were placed into larger plastic containers (60 cm long × 40 cm wide × 12 cm deep) containing a 1-cm deep layer of sterile saw dust. The lid of the container had a 40-cm-diameter mesh-covered window for ventilation. Pupae were collected daily until the larvae finished jumping from the rearing tray. Three batches of experiment were conducted for autoclaved and live Proteus sp. treatments and the control gel-based larval diet.

Quality parameter evaluations

The quality parameters of the flies reared on the different bacteria-added gel larval diets and the control were evaluated by assessing egg hatch (%), larval duration (days), pupal weight (mg), pupal yield (number), sex ratio (male %), adult emergence (%), flight ability (%), and survival (%) under stress. All quality parameters including survival under stress were estimated and performed under controlled laboratory condition (27 ± 1 °C, 65 ± 5% and 14 h L:10 h D).

Egg hatch percentage

To estimate the proportion of eggs hatched, four sets of 100 eggs were spread on a 1 × 3.5 cm strip of wet blue sponge cloth and incubated in covered 55-mm Petri dishes containing the larval diets. Unhatched eggs were counted and recorded after 5 days. To calculate the mean percentage of eggs hatched, the number of unhatched eggs was subtracted from 100, then multiplied by 100.

Larval duration

Larval duration (days) was determined by recording and collecting larvae first observed exiting from the larval diet up to 5 days of pupal collection, and estimated the mean larval period.

Pupal weight

Pupae were collected for 5 days after larvae began exiting the diet and pupating in the saw dust. Four sets of 100 pupae per larval diet were weighed to obtain the mean weight (mg). For each larval diet, pupae from each daily collection were weighed 1 day after collection. Pupal weight (mg) from each daily collection was estimated by dividing the total weight of the pupae by the mean weight of the four sets of 100 pupae and multiplying by 100.

Pupal yield

Pupal yield was estimated by dividing the total pupal weight (from 450 ml of each treatment diet) by the mean weight of the four sets of 100 pupae and multiplying by 100.

Adult emergence and flight ability

Four sets of 100 pupae from the collection day with highest pupal recovery were used to assess adult emergence and the percentage of fliers. Two days before the adults emerged, four sets of 100 pupae reared on each larval diet were placed in separate 55-mm plastic Petri dish lids. The pupae dishes were then centered on 90-mm Petri dishes lined with black paper. A100-mm tall black plexi glass tube (94 mm inner diameter, 3 mm thickness) was placed on the Petri dish, and assessments were performed following previously described procedures [52]. To minimize fly-back, flies that escaped from the tube were removed daily. The flight ability test was conducted in a laboratory at 27 ± 1 °C, 65 ± 5% and a 14:10 light:dark cycle.

Sex ratio

Four sets of 100 pupae were counted from each larval diet and placed into 1-L cylindrical plastic containers (8 cm in diameter) with a mesh section on one side (5.8 cm) for ventilation. These pupae were allowed to emerge and then scored for calculation of sex ratio.

Effect of gut bacteria on adult survival under food and water starvation

Within 4 h of adult emergence, 25 males and 25 females were placed in a large Petri dish (70 × 15 mm) with a mesh-covered window in the lid and a hole approximately 15 mm in the center. All dishes were kept in the dark at 27 °C and 65% RH, until the last fly died. Dead flies were sorted, counted and removed from the Petri dishes on inspection twice daily (every 12 h). The surviving flies from each live and autoclaved bacteria-treated and control diet were counted.

Statistical analysis

Within each of the three fly batches assessed, four replicates were run for each biological parameter. All data presented in this study are expressed as the mean ± standard error (SE) and were analyzed by ANOVA using Minitab, version 17. Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) test was used to determine significant differences among diet means.

Results

Twelve bacterial species were isolated and identified from B. dorsalis eggs, third instars larval gut and adults gut. The common bacterial genera were Acinetobacter, Alcaligenes, Citrobacter, Pseudomonas, Proteus, and Stenotrophomonas. The physical characteristics of the B. dorsalis bacterial colonies at different life stages appeared similar in both culture media, with most being cream and yellow in color, while some were red. No fungi or yeasts were observed. Gram-negative and rod-shaped bacteria were the most abundant. Using API, similar gut bacterial species identified from the larval and adult guts belonged to the Enterobacteriaceae family (Table 1).

16S rRNA gene sequences

16S rRNA gene sequences of the bacterial isolates, AC1, AC11, AC12, AC15 and AC20, from B. dorsalis eggs, the guts of larvae, and adults that were isolated and identified by conventional methods and API were closely related to Proteus mirabilis and Pantoea agglomerans. Molecular phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 1) of the isolates from the B. dorsalis larval gut was performed by a Bootstrap consensus tree using the maximum likelihood method. The analysis involved 13 nucleotide sequences. Bootstrap values (1000 replicates) were placed at the nodes.

Evaluation of quality parameters

The quality parameters measured for B. dorsalis reared on gut bacteria supplements and control gel diets are shown in Table 2.

Egg hatch percentage

Parental egg hatch was higher in the live than autoclaved Proteus-added diets but did not differ significantly from that of the control diet (F = 1.02; d.f. = 2, 6; P = 0.415) (Table 2).

Pupal yield

Provisions of live Proteus sp. did not increase the B. dorsalis pupal yield compared to the control gel diet (F = 1.14; d.f. = 2, 6; P = 0.379). Autoclaved bacterial supplements did not differ significantly from the live or control diets.

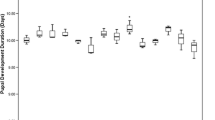

Larval duration

Diets enriched with both live and autoclaved Proteus sp. did not significantly reduce the duration of the B. dorsalis larval stage compared to the control diet. Larval stage duration for all diets ranged from 7 to 11 days and did not differ significantly among treatments (F = 0.08; d.f. = 2, 6; P = 0.925).

Pupal weight

Neither live nor autoclaved Proteus supplements affected pupal weight (F = 0.07; d.f. = 2,6; P = 0.932).

Adult emergence and flight ability

Significantly more adults fed the live Proteus-treated diet emerged than those fed the control and autoclaved bacteria-treated diets (F = 9.07; d.f. = 2,6;P = 0.015). Proteus supplements did not influence flight ability (F = 0.30; d.f. = 2,6; P = 0.751) of B. dorsalis compared to those fed the control diet.

Sex ratio

The percentage of B. dorsalis males was significantly higher in autoclaved Proteus sp. treated larval diet compared to the live Proteus sp. treated diet and control diet (F = 28.68; d.f. = 2,6; P = 0.001). However, % male from control diet was significantly lower from those of live and autoclaved Proteus sp. treated diets.

Survival under stress

Longevity for the food and water deprived bacterial treatments significantly predicted adult life span (F = 11.86; d.f. = 2,6; P = 0.008). Survival rates of flies fed live and autoclaved Proteus-treated diets were higher than that of those raised on the control diet (Table 2).

Discussion

We isolated and identified 12 bacterial genera from B. dorsalis eggs, third instars larval gut, and adults gut using culture-based approaches (Table 1). Using 16S rRNA techniques, we established the identity of the larval gut bacterial species, P. mirabilis, to test as a probiotic dietary supplement. Positive probiotic effects on B. dorsalis quality control parameters were recorded for percentage of adult emergence, and longevity under stress, which are important factors for SIT application. Enriching the gel-based larval diet with Proteus sp. improved adult emergence (92.33%), male formation (57.38%), and survival (83.00%) under stress without affecting B. dorsalis’ egg hatching, pupal yield, pupal weight, larval duration, or flight ability compared to the control diet. Live bacteria appeared to have more potential (except percentage male) than autoclaved bacteria or the control diet (Table 2). The present gel-based larval diet appeared to be more homogenous and easier to handle when using gut bacteria as a dietary supplement for mass rearing B. dorsalis under controlled laboratory conditions.

B. dorsalis gut-associated bacterial community diversity has been reported by several authors using different isolation and characterization procedures [11, 12, 26,27,28,29]. Using next-generation sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene, a diverse group of symbiotic bacteria representing six phyla (Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Cyanobacteria, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Tenericutes) has been reported in the gut of B. dorsalis [28]. PCR-DGGE revealed the composition and diversity of the bacterial community to include Klebsiella, Citrobacter, Enterobacter, Pectobacterium and Serratia as the most representative species in adult B. dorsalis [26]. Based on molecular identification, B. dorsalis females predominantly harbored E. cloacae, E. asburiae and C. freundii, while Providencia rettgerii, K. oxytoca, E. faecalis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa dominated in male B. dorsalis [29].

In the present study, the most common genera identified in B. dorsalis were Acinetobacter, Alcaligenes, Citrobacter, Pseudomonas, Proteus, and Stenotrophomonas. This is consistent with previous studies that reported Enterobacteriaceae (Proteobacteria) as the most dominant family associated with tephritids [6, 7, 21,22,23, 25, 36, 53]; however, it contradicts recent reports that Enterococcaceae (Firmicutes) was the most dominant taxon in all life stages of B. dorsalis except the pupae [30]. We also recorded the presence of Enterococcus in the adult B. dorsalis gut. Andongma et al. [30] predicted that the presence of Enterococcaceae in the gut of B. dorsalis may help boost its immune system. However, most of the studies related to isolation and identification of gut bacterial community used adult male/female of either cultivable or wild B. dorsalis [12, 26, 27, 29]. Our goal was to identify cultivable bacterial species from B. dorsalis eggs, and larval and adult guts to identify suitable species for potential probiotic application.

The larval diet-based probiotic application of live bacteria or autoclaved Proteus sp. in our study did not negatively affect egg hatch, pupal yield, pupal weight, larval duration or flight ability of B. dorsalis. Larval diet-based probiotic application of Enterobacter sp., improved pupal and adult productivity and increased development by shortening the immature stages for male C. capitata [40]. It has been suggested that the probiotic diet’s continuous effect on med fly development might be due to Enterobacter sp. establishment in the larval gut supporting the host metabolism through nitrogen fixation and pectinolytic activities [4, 23].

The significantly higher emergence of B. dorsalis adults recorded here, using both live and autoclaved Proteus sp. compared to the control diet, contrasted with reports for GSS Z. cucurbitae [18]. B. dorsalis survival during limiting starvation conditions using both live and autoclaved Proteus sp. was significantly higher than for those reared on the control diet without probiotics. These results partly agree with those for GSS Z. cucurbitae where an autoclaved probiotic diet significantly enhanced adult survival rate compared with the non-probiotic diet [18]. Conversely, adult C. capitata survival rate on the killed probiotic diet did not differ from those reared on the ‘live probiotic’ diet [22]. Both studies noted that the autoclaved bacteria-added diet had the advantages of being more convenient and secure in handling than the live bacterial diet. In this study, the live gut bacterial species had more influence on some quality parameters of B. dorsalis than the autoclaved bacteria, but they did not always differ significantly from the control flies. Thus, gut microbiota usage may act on certain quality parameters of some fruit flies, while other parameters remain unaffected. However, it is difficult to compare different findings within the same species or among different fruit fly species due to the use of different bacterial strains with varying experimental conditions [7, 18, 24, 40].

The life traits of different fruit flies may be affected by diet and rearing procedures [54,55,56,57]. Several studies reported a relationship between the diet’s nutritive value and optimal development of different fruit flies such as C. capitata, B. dorsalis, Z. cucurbitae, B. tryonii and different Anastrepha species. High productivity of a gel diet in B. tryoni was recently reported [58] when compared with liquid [52] and solid diets. The homogeneity of different diet ingredients in the gel diet was suggested to be important in larval rearing. Here, adding the gut bacteria, Proteus sp. to a gel-based larval diet may have provided an additional nutrient source such as Enterobacter sp. [18], with more homogeneity and an increased diet ingestion rate, which eventually facilitated larvae to accumulate nutritional reserves, thus increasing adult emergence (reducing immature stage mortality), higher male production, and longevity under stress. Notably, these positive effects are important for mass rearing and large-scale SIT operational programs. Significantly more males resulted when Proteus sp. was added to the gel diet than the control diet, which might be important in supporting SIT applications since males are the active component of SIT.

Several investigations have been performed on gut bacterial manipulation during the adult stage to enhance male mating competitiveness. Irradiated ‘Vienna 8’ GSS sterile med fly males improved significantly after being fed Klebsiella sp. [36]; however, no increase in mating percentage of fertile male med flies after adult antibiotic treatment was observed [13]. However, mating competitiveness tests using probiotics were not performed in this study and thus require future investigation. Recent reviews [59, 60] reported the possible function of insect gut communities and their effects on fitness. To our knowledge, few studies on Tephritidae have reported adding bacteria to the larval diet [24, 40, 61] and adult food [24, 35, 36, 61, 62], and those studies were performed mainly on med flies. However, some reports conclude that gut bacteria may serve as lures and biocontrol agents in B. dorsalis and B. zonata [10,11,12]. However, our study showed that the gut-associated bacteria, Proteus sp. improved certain quality parameters in B. dorsalis as were reported using Enterobacter sp. in C. capitata [24, 40] and GSS Z. cucurbitae [18] larval diets. These microbiotas could be exploited to produce better quality target insects for SIT applications.

Conclusion

The larval gut bacterial species identified during the present study through culture-based approaches belonged to the Enterobacteriaceae family. Our gel-based larval diet for mass rearing B. dorsalis offered opportunities for advanced laboratory studies by manipulating different nutrients and adding gut bacterial isolates. Enriching the gel diet with gut bacteria improved some B. dorsalis quality parameters without adversely affecting their rearing. The gut bacteria, Proteus sp., led to significantly more adult emergence, male formation, and survival. This supports the idea that probiotics can be used in conjunction with SIT. Further investigations can be performed using different macro and micronutrients (yeast products/vitamins/oils) to improve gel-based larval diets for B. dorsalis rearing. The effect of probiotics on mating competitiveness of B. dorsalis should be made in future. More beneficial gut microbiota could be exploited to produce higher quality sterile flies for SIT field application as well as for other future biotechnological applications [63].

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AERE:

-

Atomic energy research establishment

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- API:

-

Analytical profile index

- BLAST:

-

Basic local alignment search tool

- D:

-

Dark

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- EDTA:

-

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- ESBL:

-

Extended spectrum beta-lactamase

- GSSs:

-

Genetic sexing strains

- HSD:

-

Honest significant difference

- IBD:

-

Insect biotechnology division

- IFRB:

-

Institute of food and radiation biology

- L:

-

Light

- MEGA 6:

-

Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0.

- NCBI:

-

National center for biotechnology information

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffered saline

- PCR-DGGE:

-

Polymerase chain reaction denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis

- RH:

-

Relative humidity

- RNA:

-

Ribonucleic acid

- SE:

-

Standard error

- SIT:

-

Sterile insect technique

- TAE:

-

Tris, acetate, either

References

Dillon R, Dillon V. The gut of insects: nonpathogenic interactions. Ann Rev Entomol. 2004;49:71–92.

Ridley EV, Wong AC, Westmiller S, Douglas AE. Impact of the resident microbiota on the nutritional phenotype of Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36765. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036765.

Robacker DC, Lauzon CR, Patt J, Margara F, Sacchetti P. Attraction of Mexican fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) to bacteria: effects of culturing medium on odour volatiles. J Appl Entomol. 2009;133:155–63.

Ben-Yosef M, Pasternak Z, Jurkevitch E, Yuval B. Symbiotic bacteria enable olive flies (Bactrocera oleae) to exploit intractable sources of nitrogen. J Evol Biol. 2014;27:2695–705.

Douglas AE. Nutritional interactions in insect-microbial symbiosis: aphids and their symbiotic bacteria Buchnera. Ann Rev Entomol. 1998;43:17–37.

Behar A, Yuval B, Jurkevitch E. Gut bacterial communities in the Mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata) and their impact on host longevity. J Insect Physiol. 2008;54:1377–83.

Ben-Ami E, Yuval B, Jurkevitch E. Manipulation of the microbiota of mass-reared Mediterranean fruit flies Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) improves sterile male sexual performance. ISME J. 2010;4:28–37.

Ben-Yosef M, Pasternak Z, Jurkevitch E, Yuval B. Symbiotic bacteria enable olive fly larvae to overcome host defenses. Royal Soc Open Sci. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150170 or via http://rsos.royalsocietypublishing.org.

Lauzon CR, Potter S, Prokopy RJ. Degradation and detoxification of the dihydrochalconephloridzin by Enterobacter agglomerans, a bacterium associated with the apple pest, Rhagoletis pomonella (Walsh) (Diptera:Tephritidae). Environ Entomol. 2003;32(5):953–62.

Reddy K, Sharma K, Singh S. Attractancy potential of culturable bacteria from the gut of peach fruit fly, Bactrocera zonata (Saunders). Phytoparasitica. 2014;42:691–8.

Shi Z, Wang L, Zhang H. Low diversity bacterial community and the trapping activity of metabolites from cultivable bacteria species in the female reproductive system of the Oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis Hendel (Diptera: Tephritidae). Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:6266–78. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13056266 PMID: 22754363.

Wang H, Jin L, Peng T, Zhang H, Chen Q, Hua Y. Identification of cultivable bacteria in the intestinal tract of Bactrocera dorsalis from three different populations and determination of their attractive potential. Pest Manage Sci. 2013;70:80–7.

Ben-Yosef M, Jurkevitch E, Yuval B. Effect of bacteria on nutritional status and reproductive success of the Mediterranean fruit fly Ceratitis capitata. Physiol Entomol. 2008;33:145–54.

Estes AM, Hearn DJ, Burrack HJ, Rempoulakis P, Pierson EA. Prevalence of Candidatus Erwinia dacicola in wild and laboratory olive fruit fly populations and across developmental stages. Environ Entomol. 2012;41:265–74. https://doi.org/10.1603/EN11245 PMID: 22506998.

Sacchetti P, Ghiardi B, Granchietti A, Stefanini FM, Belcari A. Development of probiotic diets for the olive fly: evaluation of their effects on fly longevity and fecundity. Ann Appl Biol. 2014;164:138–50.

Prabhakar CS, Sood P, Kanwar SS, Sharma PN, Kumar A, Mehta PK. Isolation and characterization of gut bacteria of fruit fly, Bactrocera tau (Walker). Phytoparasitica. 2013;41:193–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12600-012-0278-5.

Luo M, Zhang H, Chen J, Du Y, He L, Ji Q. Isolation and identification of bacteria in the intestinal tract of adult Bactrocera tau (Walker) (Diptera:Tephritidae). J Fijian Agric Forest Univ (Natural Sci). 2016;45:4–13.

Yao M, Zhang PC, Xiaohong G, Dan W, Qinge J. Enhanced fitness of a Bactrocera cucurbitae genetic sexing strain based on the addition of gut-isolated probiotics (Enterobacter spec.) to the larval diet. Entomol Exp Appl. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1111/eea.12529.

Hoi-Sen Y, Sze-Looi S, Kah-Ooi C, Phaik-Eem L. High diversity of bacterial communities in developmental stages of Bactrocera carambolae (Insecta: Tephritidae) revealed by illumina MiSeq sequencing of 16S rRNA gene. Curr Microbiol. 2017;74(9):1076–82.

Thaochan N, Drew RAI, Hughes JM, Vijaysegaran S, Chinajariyawong A. Alimentary tract bacteria isolated and identified with API-20E and molecular cloning techniques from Australian tropical fruit flies, Bactrocera cacuminata and B. tryoni. J Insect Sci. 2010;10:131–6.

Kuzina LV, Peloquin JJ, Vacek DC, Miller TA. Isolation and identification of bacteria associated with adult laboratory Mexican fruit flies, Anastrepha ludens (Diptera: Tephritidae). Curr Microbiol. 2001;42:290–4.

Aharon Y, Pasternak Z, Ben Yosef M, Behar A, Lauzon C, Yuval B, et al. Phylogenetic, metabolic, and taxonomic diversities shape Mediterranean fruit fly microbiotas during ontogeny. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;79:303–13. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02761-12 PMID: 23104413.

Behar A, Yuval B, Jurkevitch E. Enterobacteria-mediated nitrogen fixation in natural populations of the fruit fly Ceratitis capitata. Mol Ecol. 2005;14:2637–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02615.x PMID:16029466.

Hamden H, Guerfali MM, Fadhl S, Saidi M, Chevrier C. Fitness improvement of mass-reared sterile males of Ceratitis capitata (Vienna 8 strain) (Diptera: Tephritidae) after gut enrichment with probiotics. J Econ Entomol. 2013;106:641–7. https://doi.org/10.1603/EC12362 PMID: 23786049.

Behar A, Jurkevitch E, Yuval B. Bringing back the fruit into fruit fly-bacteria interactions. Mol Ecol. 2008;17:1375–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03674.x PMID: 18302695.

Wang H, Jin L, Zhang H. Comparison of the diversity of the bacterial communities in the intestinal tract of adult Bactrocera dorsalis from three different populations. J Appl Microbiol. 2011;110:1390–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05001.x PMID: 21395953.

Pramanik MK, Mahin A-A, Khan M, Miah AB. Isolation and identification of mid-gut bacterial community of Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) (Diptera: Tephritidae). Res J Microbiol. 2014;9:278–86. https://doi.org/10.3923/jm.2014.278.286.

Hoi Sen Y, Sze-Looi S, Kah OC, Phaik Eem L. Microbiota associated with Bactrocera carambolae and B. dorsalis (Insecta: Tephritidae) revealed by next-generation sequencing of 16S rRNA gene. Meta Gene. 2016;11(C). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mgene.2016.10.009.

Nagalakshmi RG, Selvakumar G, Abraham V, Sudhagar S, Ravi M. Diversity of the cultivable gut bacterial communities associated with the fruit flies Bactrocera dorsalis and Bactrocera cucurbitae (Diptera: Tephritidae). Phytoparasitica. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12600-017-0604-z.

Andongma AA, Lun W, Yong-Cheng D, Li P, Nicolas D, Jennifer AW, Chang-Ying N. Pyrosequencing reveals a shift in symbiotic bacteria populations across life stages of Bactrocera dorsalis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9470. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09470.

Daser U, Brandl R. Microbial gut floras of eight species of tephritids. Biol J Linnean Soc. 1992;45:155–65.

Drew RAI, Lloyd AC. Relationship of fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) and their bacteria to host plants. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1987;80(5):629–36.

Sood P, Nath A. Colonization of marker strains of bacteria in fruit fly, Bactrocera tau. Indian J Agric Res. 2005;39(2):103–9.

Morrow JL, Frommer M, Shearman DCA, Riegler M. The microbiome of field-caught and laboratory adapted Australian tephritid fruit fly species with different host plant use and specialisation. Microb Ecol. 2015;70:498–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-015-0571-1 PMID: 25666536.

Niyazi N, Lauzon CR, Shelly TE. Effect of probiotic adult diets on fitness components of sterile male Mediterranean fruit flies (Diptera:Tephritidae) under laboratory and field cage conditions. J Econ Entomol. 2004;97:157–1580.

Gavriel S, Jurkevitch E, Gazit Y, Yuval B. Bacterially enriched diet improves sexual performance of sterile male Mediterranean fruit flies. J Appl Entomol. 2011;135:564–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0418.2010.01605.x.

Daifeng C, Zijun G, Markus R, Xi Z, Guangwen L, Xu Y. Gut symbiont enhances insecticide resistance in a significant pest, the oriental fruit fly Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel). Microbiome. 2017;5:13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-017-0236-z.

Zindel R, Gottlieb Y, Aebi A. Arthropod symbioses: a neglected parameter in pest- and disease-control programmes. J Appl Ecol. 2011;48:864–72.

Lauzon CR, Potter SE. Description of the irradiated and nonirradiated midgut of Ceratitis capitata Wiedemann (Diptera: Tephritidae) and Anastrepha ludens Loew (Diptera: Tephritidae) used for sterile insect technique. J Pest Sci. 2012;85:217–26.

Augustinos AA, Kyritsis GA, Papadopoulos NT, Abd-Alla AMM, Carlos C, Bourtzis K. Exploitation of the medfly gut microbiota for the enhancement of sterile insect technique: use of Enterobacter sp. in larval diet-based probiotic applications. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136459.

Allwood AJ, Chinajariyawong A, Drew RAI, Hamacek EL, Hancock DL, Hangsawad C, Jipanin JC, Jirasurat M, Kong KC, Kritsaneepaiboon S, Leong CTS, Vijaysegaran S. Host plants for fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) in South East Asia. Raff Bull Zool Suppl. 1999;7:1–92.

Nidchaya A, Suksom C, Watchreeporn O, Carmela RG, Gerald F, Anna RM, Sujinda T. The utility of microsatellite DNA markers for the evaluation of area-wide integrated pest management using SIT for the fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel), control programs in Thailand. Genetica. 2011;139:129–40.

Dyck VA, Hendrichs JP, Robinson AS, editors. The sterile insect technique: principles and practice in area-wide integrated pest management. Dordrecht: Springer; 2005.

Luc L, Roger IV, Bruce M, Rudolph P, Jame CP. Evaluation of cue-lure and methyl eugenol solid lure and insecticide dispensers for fruit fly (Diptera:Tephritidae) monitoring and control in Tahiti. Florida Entomol. 2011;94(3):510–6.

Suksom C, Sunyanee S, Phatchara K, Weera K, Weerawan S, Nongon P. Inter-regional mating compatibility among Bactrocera dorsalis populations in Thailand (Diptera,Tephritidae). Zookeys. 2015;540:299–311.

Ye H, Jian-Hong L. Population dynamics of the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae) in the Kunming area, southwestern China. Insect Sci. 2005;12(5):387–92.

Antonios AA, Elena D, Aggeliki G-P, Elias DA, Carlos C, George T, Kostas B, Penelope M-T, Antigone Z. Cytogenetic and symbiont analysis of five members of the B. dorsalis complex (Diptera, Tephritidae): no evidence of chromosomal or symbiont-based speciation events. Zookeys. 2015;540:273–98.

Khan M, Hossain MA, Khan SA, Islam MS, Chang CL. Development of liquid larval diet with modified rearing system for Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) (Diptera: Tephritidae) for the application of sterile insect technique. ARPN J Agric Biol Sci. 2011;6:52–7.

Hasegawa M, Kishino H, Yano T. Dating the human-ape split by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. J Mole Evol. 1985;22:160–74.

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst197 PMID: 24132122.

Drzewiecka D. Significance and roles of Proteus spp. bacteria in natural environments. Microb Ecol. 2016;72(4):741–58.

Khan M. Potential of liquid larval diets for mass rearing of Queensland fruit fly, Bactrocera tryoni (Froggatt) (Diptera: Tephritidae). Aust J Entomol. 2013;52:268–76.

Capuzzo C, Firrao G, Nazzon L, Squartini A, Girolami V. ‘Candidatus Erwiniadacicola’, a coevolved symbiotic bacterium of the olive fly Bactrocera oleae (Gmelin). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:1641–7.

Economopoulos AP, Al-Taweel AA, Bruzzone ND. Larval diet with a starter phase for mass-rearing Ceratitis capitata: substitution and refinement in the use of yeasts and sugars. Entomol Exp Appl. 1990;55:239–46.

Kaspi R, Mossinson S, Drezner T. Effects of larval diet on development rates and reproductive maturation of male and female Mediterranean fruit flies. Physiol Entomol. 2002;27:29–38.

Chang CL. Evaluation of yeasts and yeast products in larval and adult diets for the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis, and adult diets for the medfly, Ceratitis capitata, and the melon fly, Bactrocera curcurbitae. J Insect Sci. 2009;9:1–9.

Chang CL, Vargas RI, Caceres C, Jang E, Cho IK. Development and assessment of a liquid larval diet for Bactrocera dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae). Ann Entomol Soc Am. 2006;99:1191–8.

Tahereh M, Taylor PW, Ponton F. High productivity gel diets for rearing of Queensland fruit fly, Bactrocera tryoni. J Pest Sci. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-016-0813-0.

Douglas AE. Multi organismal insects: diversity and function of resident microorganisms. Ann Rev Entomol Ann Rev Inc. 2015;60:17–34. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020822 PMID: 25341109.

Engel P, Moran NA. The gut microbiota of insects-diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37:699–735. https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6976.12025 PMID: 23692388.

Georgios AK, Antonios AA, Carlos C, Kostas B. Med fly gut microbiota and enhancement of the sterile insect technique: similarities and differences of Klebsiella oxytoca and Enterobacter sp. AA26 probiotics during the larval and adult stages of the VIENNA 8D53+ genetic sexing strain. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2064. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02064.

Rull J, Lasa R, Rodriguez C, Ortega R, Velazquez OE, Aluja M. Artificial selection, pre-release diet, and gut symbiont inoculation effects on sterile male longevity for area-wide fruit-fly management. Entomol Exp Appl. 2015;157(3):325–33.

Berasategui A, Shukla S, Salem H, Kaltenpoth M. Potential applications of insect symbionts in biotechnology. Appl Microb Biotech. 2016;100:1567–77.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Dilruba Ahmed, Head, Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (iccdr,b), Mohakhali, Dhaka, Bangladesh for identifying the B. dorsalis gut bacterial community using conventional and API kits. The authors are also thankful to Dr. Kostas Bourtzis, Joint FAO/IAEA (Food and Agriculture Organization/International Atomic Energy Agency), Vienna, Austria and the anonymous reviewer for their kind advice to improve the manuscript.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Biotechnology Volume 19 Supplement 2, 2019: Proceedings of an FAO/IAEA Coordinated Research Project on Use of Symbiotic Bacteria to Reduce Mass-rearing Costs and Increase Mating Success in Selected Fruit Pests in Support of SIT Application: biotechnology. The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://bmcbiotechnol.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-19-supplement-2.

Funding

This research was part of the Joint FAO/IAEA Coordinated Research Project (CRP) of the Insect Biotechnology Division, Institute of Food and Radiation Biology, Bangladesh Atomic Energy Commission (via FAO/IAEA CRP No.-17011/R4 to Dr. Mahfuza Khan).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MK contributed in the conception and design of the study. MK, MAB, and NS participated in the development of the method and the validation and analyzed the data. KS, KFS, and MAH participated in the microbiologic analysis. MK wrote the manuscript. MK and SAK reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution IGO License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source is given.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, M., Seheli, K., Bari, M.A. et al. Potential of a fly gut microbiota incorporated gel-based larval diet for rearing Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel). BMC Biotechnol 19 (Suppl 2), 94 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12896-019-0580-0

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12896-019-0580-0