Abstract

Background

In general, reproductive performance exhibits nonlinear changes with age. Specifically, reproductive performance increases early in life, reaches a peak, and then declines later in life. Reproductive ageing patterns can also differ among individuals if they are influenced by individual-specific strategies of resource allocation between early-life reproduction and maintenance. In addition, the social environment, such as the number of available mates, can influence individual-specific resource allocation strategies and consequently alter the extent of individual differences in reproductive ageing patterns. That is, females that interact with more partners are expected to vary their copulation frequency, adopt a more flexible reproductive strategy and exhibit greater individual differences in reproductive ageing patterns.

Methods

In this study, we evaluated the effect of mating with multiple males on both group- and individual-level reproductive ageing patterns in females of the bean bug Riptortus pedestris by ensuring that females experienced monogamous (one female with one male) or polyandrous conditions (one female with two males).

Results

We found that group-level reproductive ageing patterns did not differ between monogamy-treatment and polyandry-treatment females. However, polyandry-treatment females exhibited among-individual variation in reproductive ageing patterns, while monogamy-treatment females did not.

Conclusion

Our findings provide the first empirical evidence regarding the influence of the social environment on individual variation in reproductive ageing patterns. We further suggest that the number of potential mates influences group- and individual-level reproductive ageing patterns, depending on which sex controls mating. We encourage future studies to consider interactions between species-specific mating systems and the social environment when evaluating group- and individual-level reproductive ageing patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A senescent decline in reproductive performance has been documented across many animal taxa [1,2,3]. In insects, older males are less likely to exhibit high courtship rates or frequent mating attempts, while older females display reduced oviposition rates [4]. This reproductive ageing in insects might simply be due to somatic deterioration with ageing. However, reproductive ageing can also be explained by the disposable soma theory which suggests that individuals allocate limited resources between reproduction and the maintenance of their soma [5, 6]. As a result, the nonlinear pattern of reproductive ageing can vary depending on the trade-off between allocating resources to early-life reproduction and body maintenance [7,8,9]. For example, high investment in early-life reproduction causes a steep increase and a peak in reproductive performance, followed by a sharp decline; individuals consequently exhibit a shortened lifespan (i.e., strongly negative quadratic reproductive ageing) due to the high energetic costs of early-life egg production [10, 11] and high rates of injury or infections obtained from multiple copulations [12, 13]. At the other extreme, low or moderate levels of reproductive investment in early life result in a gradual (rather than steep) increase in reproductive performance, a peak, and then a plateau (i.e., weakly negative quadratic reproductive ageing), resulting in a relatively long lifespan. Moreover, as nonlinear reproductive ageing patterns are determined by resource allocation strategies, they vary depending on environmental conditions that affect investment in early-life reproduction [14,15,16], such as food availability, population density and weather conditions (reviewed in [15]). However, previous studies concerning the effects of environmental factors on reproductive ageing patterns have focused on linear rather than nonlinear patterns [15].

In particular, the number of available male mating partners can be a potential determinant of nonlinear reproductive ageing patterns in females. Reproductive ageing patterns are expected to differ between females allowed to mate with multiple males (polyandrous females) and females that mate with only one male throughout their lifetime (monogamous females). Females can increase longevity and egg production rates by mating with multiple partners if they receive direct benefits from males during mating, such as nuptial gifts or nutritious ejaculates [17,18,19], and if these benefits offset the costs of reproduction. However, if males do not provide such direct benefits to females, polyandrous females are expected to experience accelerated reproductive ageing compared to monogamous females. Polyandrous females may invest more in early-life reproduction because of frequent mating with multiple males [9, 20]. Compared to monogamous conditions, in polyandrous conditions, females may also suffer from increased sexual harassment. Thus increases in both early-life reproductive performance and costs under polyandrous conditions can reduce the lifespans of polyandrous females more sharply than those of monogamous females. Alternatively, differences in reproductive ageing patterns between polyandrous and monogamous females might occur due to selection. When early-life reproductive costs are higher in polyandrous females than in monogamous females, the loss of females with high early-life reproductive output (selective disappearance, e.g., [21]) can be greater among polyandrous females than monogamous females. Therefore, both mechanisms (increased reproductive costs under polyandrous conditions and selective disappearance) predict that polyandrous females have more negative quadratic reproductive ageing curves than monogamous females.

In addition, differences in nonlinear reproductive ageing patterns between monogamous and polyandrous females in insect species are expected to depend on which sex controls mating. In insect species where females are coerced into copulation and males control mating, females are more likely to concede into superfluous copulations as the number of males increases [22,23,24]. These superfluous copulations result in higher costs of early-life reproduction for polyandrous females than for monogamous females, leading to faster reproductive ageing. In contrast, in insect species where males cannot coerce females to mate but instead must court them, differences in reproductive ageing patterns between monogamous and polyandrous females are expected to be less pronounced or nonsignificant. Because females control mating in such species, female copulation frequency might not increase as a function of the number of potential mates (reviewed in [24]). Thus, in such species, both polyandrous and monogamous females experience similar reproductive costs and exhibit equivalent patterns of reproductive ageing. However, even if females control mating, females under polyandrous conditions may experience increased male mating attempts and harassment, and thus incur higher reproductive costs, which could lead to faster reproductive ageing compared to monogamous females.

Moreover, female individuals are expected to vary in nonlinear reproductive ageing patterns, and the extent of individual differences in nonlinear reproductive ageing patterns within monogamous females may differ from that within polyandrous females; such differences are also expected to depend on which sex controls mating. Individuals are expected to differ in life-history strategies according to resource allocation to early-life reproduction or body maintenance [25,26,27], potentially generating the among-individual variation in nonlinear reproductive ageing patterns. Because individual (and genetic) variation in a trait is the raw material on which natural selection acts, the extent of individual differences in reproductive ageing patterns implies the evolvability of life-history strategies. Moreover, as genetic variation in a trait likely depends on environmental conditions (e.g., genetic variance can increase in stressful environments due to cryptic genetic variation [28]), the extent of individual variation in reproductive ageing patterns can also increase or decrease according to environmental conditions, implying that environmental conditions influence the evolution of life-history strategies. For example, in insect species where males exhibit coercive mating, all females appear to experience high rates of male harassment and superfluous copulations when males are in excess (polyandrous condition). As a result, in polyandrous conditions, coercive males are predicted to force all females to increase their early-life reproductive investment. Consequently, in insect species in which males coerce females to mate, individual differences in reproductive ageing patterns among polyandrous females are expected to be smaller than those among monogamous females. In contrast, the opposite is expected in insect species where females can reject male mating attempts and control mating. In such species, excess males provide readily available mating opportunities for females. As a result, in polyandrous conditions, some females may increase early-life reproductive investment and senesce faster, whereas others may maintain a moderate reproductive rate and focus on mating with high-quality males throughout their lifetime. Thus, in insect species where females control mating, female individuals in polyandrous conditions are expected to adopt more diverse reproductive strategies and exhibit greater individual variation in the age at peak reproductive investment, resulting in larger individual differences in reproductive ageing patterns compared to female individuals in monogamous conditions. Taken together, the species-specific mating system is predicted to influence the impact of social conditions (e.g., the number of potential mates) on the extent of individual variation in reproductive ageing patterns. However, to date, evidence of individual variation in nonlinear reproductive ageing patterns is lacking [29,30,31], and little is known about the relationship among mating systems, mate availability and individual variation in reproductive ageing patterns.

Here, we investigated differences in nonlinear reproductive ageing patterns between monogamous and polyandrous female bean bugs (Riptortus pedestris) at the group and individual levels. The bean bug R. pedestris (Hemiptera: Alydidae), a major pest of leguminous crops in East Asia, is a multivoltine species that produces two to three generations per year [32, 33]. Females become sexually mature within two weeks of eclosion and start to oviposit [34]; virgin females can lay unfertilised eggs throughout their lifetime [31]. Although previous research showed that mated females do not copulate for an average of 15 to 20 days after their first mating [35], our current study revealed that females mate with males every two to three days. Females of this species are known to lay eggs throughout their lifetime and to exhibit a negative quadratic effect of age on reproductive performances [31].

We conducted two independent experiments to determine which sex of R. pedestris controlled mating decisions (Experiment 1) and to investigate how group- and individual-level reproductive ageing patterns in females changed in response to mate availability (Experiment 2). In Experiment 1, we placed one female with a single male (and with another male prevented from accessing the female, “monogamy” treatment) or one female with two males (“polyandry” treatment), monitored mating status every 10 min for a week and then compared the copulation frequency and duration of the focal male and female between mating contexts. In Experiment 2, we reared individual females isolated from males (“no mating” treatment), housed with a single male (and with another male prevented from accessing the female, “monogamy” treatment) or housed with two males (“polyandry” treatment) and recorded their weekly egg production and lifespan. We predicted that females controlled copulation frequency and duration in R. pedestris because R. pedestris males are known to exhibit very obvious courtship behaviours [36]. Consequently, we predicted that individual variation in reproductive ageing patterns would be greater in polyandry-treatment females than in monogamy-treatment females.

Materials and methods

Rearing conditions

Our laboratory stock populations of R. pedestris were established in 2018 with hundreds of eggs that originated from a population maintained at the Pest Management Institute, Baekam, Gyeonggido, Korea. In each generation, stock populations were maintained in multiple (2 or 3) transparent plastic containers (20 × 20 × 40 cm), each containing an average of 150 adult individuals and provided with water and food (soybeans, Glycine max and chickpeas, Cicer arietinum) ad libitum. To generate future generations, eggs were collected on a piece of cotton placed in the containers 3 weeks after the first observation of eclosion to adulthood. We collected eggs every week, pooled them to reduce the effect of rearing containers and randomly distributed them to new containers for future generations. Stock populations and all experimental individuals were maintained at 24–27 ℃ with 40–60% relative humidity under a 17 h light:7 h dark (light: 07:00 ~ 24:00, dark: 00:00 ~ 07:00) photoperiod.

Experiment 1. Male and female mating patterns under monogamy vs. polyandry treatments

We collected newly eclosed adults from the stock populations and separated the males and females into individual home containers (females: 12 × 12 × 2 cm [width × depth × height]; males: 12 × 8 cm [diameter × height]). We kept adults in individual containers for two weeks after eclosion to ensure sexual maturation and provided food and water ad libitum. After two weeks, we randomly assigned sexually mature males to female home containers, establishing two distinct mating treatments: monogamy (n = 13) and polyandry (n = 19) (Fig. 1). In the “monogamy” treatment, we placed both an age-matched male (available for copulation) and another male isolated in a perforated, transparent, 10-ml conical tube with water and food (not available for copulation) in with a female. In this treatment, females could observe and smell isolated males through the tube but could not mate through it. In the “polyandry” treatment, we placed two age-matched males in with the female; thus both males were available for copulation. This design ensured that the sex ratio was held constant in both the monogamy and polyandry treatments to avoid any changes in female mating behaviour due to differences in the sex ratio [37,38,39,40,41,42]. To ensure that the environments were comparable among treatments, we also placed an empty conical tube in the home containers of polyandry-treatment females (Fig. 1). Because R. pedestris mating pairs display a clear end-to-end position and their copulation lasts approximately 60 to 240 min [36, 43], we were able to record the mating status of each female by photographing the home containers every 10 min. We also recorded female mating status during the dark period (00:00–07:00) by taking photographs under red LED illumination (LED T5; Zhongshan Kinsung Electronic, Zhongsan, China). One week before the experiment, we marked each male’s pronotum and abdominal sternum with enamel paint, allowing us to determine male identity in the polyandry treatment. Thus, we estimated (1) total copulation frequency and (2) total copulation duration over a week for both sexes. If a female died during the experiment (1 case in the polyandry treatment) or a male was not interested in mating (2 cases in the polyandry treatment), we excluded these data from further analysis.

Illustration of the three mating treatments. The mating treatments manipulated the number of available mates per female. a No mating treatment: one female and no males; b monogamy treatment: one female and two males (only one male available for copulation); c polyandry treatment: one female and two males (both available for copulation). The small rectangular box in the home container depicts the perforated container used to physically isolate the additional male in the monogamy treatment (in both no mating and polyandry treatments, these containers were empty). Experiment 1 employed only two treatments (monogamy vs. polyandry), whereas Experiment 2 employed all three treatments

Experiment 2. Female reproductive ageing under three different mating treatments

For this experiment, we collected newly eclosed females from stock populations and placed them in individual home containers (12 × 8 cm [diameter × height]). Females were randomly assigned to one of three mating treatments (Fig. 1): no mating (44 females), monogamy (42 females) and polyandry (44 females). Females in the no mating treatment were isolated throughout their lifetime and not housed with a male. Since virgin R. pedestris females can lay unfertilised eggs throughout their lifespan [31], we could estimate the baseline patterns of female reproductive ageing in the absence of mating costs by measuring the production of unfertilised eggs by virgin females. In the monogamy treatment, we placed an age-matched male in with the female, allowing copulation, and physically isolated another male in a perforated transparent plastic cup (4 × 6 × 6 cm [bottom diameter × height × top diameter]), similar to the treatment in Experiment 1 (Fig. 1). In the polyandry treatment, we placed two age-matched males in with the female, allowing the female to copulate freely with either male. Empty plastic cups were also placed in the home containers of the no mating and polyandry treatments to ensure comparable environments across all treatments (Fig. 1). Water and food were provided ad libitum in all home containers, and a small piece of cotton paper (2 × 2 cm) was placed in each container to induce oviposition. We counted the number of eggs laid by each female and weighed each female weekly while replacing the water and food. We also checked individual survival each day to assess longevity. If a male died, he was replaced with an age-matched male from the stock population. Thus, we estimated each female’s (1) longevity, (2) lifetime egg production and (3) weekly egg production.

Statistical analyses

Experiment 1

We used Mann–Whitney U tests to assess differences in the total copulation frequency and duration of males and females between the monogamy and polyandry treatments. When analysing the polyandry treatment data, we randomly assigned one of the two males as the “focal” male. The analysis was performed using Statistica software (version 14, TIBCO Software Inc.).

Experiment 2

We first analysed the effect of mating treatment on group-level reproductive ageing patterns (i.e., a linear or quadratic change in weekly egg production) using a univariate mixed-effects model, where weekly egg production was fitted as the response variable. In the model, we included female identity as a random effect and fitted mating treatment (a three-level factor: no mating, monogamy and polyandry), linear and quadratic ages (weeks since eclosion as adults), the age (in weeks) at the last observed reproduction and the interaction between mating treatment and other covariates (linear age, quadratic age and the age at the last observed reproduction) as fixed effects. In the model, we fitted age (in weeks) as age-1 (in weeks) to ensure that the intercepts of our models represented the number of eggs produced during the first week after eclosion as an adult. The age at the last observed reproduction was used to control selective disappearance [21]. In addition, because females did not differ in age at first egg production, we did not include the age at the first observed reproduction in the model.

We also constructed treatment-specific random intercept and slope models by adding random effects sequentially to assess among-individual variation in the linear/quadratic patterns of reproductive ageing in each treatment. In all the treatment-specific models below, we fitted weekly egg production as the response variable and included linear and quadratic ages (weeks since eclosion as adults) and the age (in weeks) at the last observed reproduction as fixed effects. We did not use within-individual mean-centring but rather chronological ages (in weeks) because within-individual mean-centring is sometimes problematic when calculating individual differences in ageing slopes [44, 45]. We started by fitting a treatment-specific univariate general linear model that did not include random effects, only fixed effects and residuals (Model 1). We then fitted a random intercept model that included female identity as a random factor to assess individual differences in the egg production rate (I effect, Model 2). We further fitted random slope models that sequentially included the random interaction of individual identity and linear age (I × AGE effect, Model 3) or quadratic age (I × AGE2 effect, Model 4) to assess among-individual variation in reproductive ageing patterns. In all the models above, residual variances were assumed to be age-specific (17 age-specific residual variances were estimated) and not correlated across ages.

All models were implemented in ASReml (version 4.2, VSN Interaction, Hemel Hempstead, UK) and solved using the restricted maximum likelihood method. We assessed the significance of fixed effects using conditional Wald F tests. The significance of variance attributable to random effects was determined using likelihood-ratio tests (LRTs) and calculated as twice the difference in log likelihood between the full model and a reduced model where the random effect of interest was removed; the P value was calculated assuming an equal mixture of P(χ2, df = 0) and P(χ2, df = 1) [46, 47]. This is indicated as “χ20/1” in the results.

In addition to comparing models that assessed individual differences in reproductive ageing patterns, we conducted an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare total lifetime egg production among the mating treatments. ANOVAs were performed using Statistica software (version 14, TIBCO Software Inc.).

Results

Experiment 1. Male and female mating patterns under monogamy vs. polyandry treatments

The total copulation frequency and duration of females did not differ between the monogamy and polyandry treatments (total copulation frequency: U = 92.5, Z = 1.21, P = 0.22; total copulation duration: U = 117.5, Z=− 0.21, P = 0.83) (Fig. 2). In contrast, males in the monogamy treatment had a total copulation frequency (U = 43.0, Z=− 3.06, P = 0.002) and duration (U = 29.5, Z=-3.59, P < 0.001) approximately double those of males in the polyandry treatment (Fig. 2).

Experiment 2. Female reproductive ageing under three different mating treatments

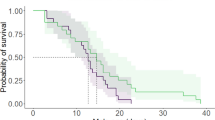

At the group level, the weekly egg production of females showed negative quadratic changes with age in all mating treatments; however, the slopes differed by treatment (Treatment × Age2 effect in Table 1; Fig. 3). The egg production of mated females in the monogamy and polyandry treatments peaked earlier, increased more sharply and decreased more sharply around the peak than that of virgin females (Treatment × Age2 effect in Table 1; Fig. 3). However, the negative quadratic change in weekly egg production did not differ between the monogamy and polyandry treatments (Fig. 3). Additionally, selective disappearance did not influence age-related changes in weekly egg production (Table 1). The total number of eggs produced did not differ among mating treatments (ANOVA, df = 2, F = 1.04, P = 0.35). In addition, mated females (monogamy- and polyandry-treatment females) tended to be heavier than virgin females (F2,126.8=2.58, P = 0.08), possibly due to the production of fertilised eggs. However, there was no difference in female body weight between the monogamy and polyandry treatments (F1,84.0=0.01, P = 0.92).

At the individual level, in all mating treatments, there were strong differences in egg production (I effect, Table 2). Individuals in the no mating or polyandry treatments varied in their linear age-related change in weekly egg production, whereas individuals in the monogamy treatment did not vary (I × AGE effect, Table 2). The negative quadratic change in weekly egg production did not differ among individuals in the no mating or monogamy treatments (Table 2; Fig. 4) but differed among individuals in the polyandry treatment (I × AGE2 effect, Table 2; Fig. 4).

Discussion

Our results show that the social environment, such as the number of potential mates, influences individual- as well as group-level patterns of reproductive ageing in females of the bean bug R. pedestris. Females that mated with only one male throughout their lifetime (i.e., monogamy-treatment females) did not vary in their nonlinear reproductive ageing patterns. However, when the number of potential mates increased (i.e., polyandry-treatment females), females exhibited variation in their nonlinear reproductive ageing patterns. This result was in line with our prediction because females control copulation frequency and duration in R. pedestris. Thus, we suggest that species-specific mating systems (e.g., which sex controls mating) and mate availability (e.g., the number of opposite-sex mating partners) can shape individual variation in reproductive ageing patterns in insects.

Mated females showed faster reproductive ageing than virgin females that laid unfertilised eggs, implying the presence of costs related to mating and the production of fertilised eggs. However, we did not find differences in lifetime egg production between monogamous and polyandrous females, indicating that their lifetime reproductive costs were similar. This idea was also supported by the lack of differences in group-level nonlinear reproductive ageing patterns between monogamous and polyandrous females. In R. pedestris, females control mating and copulate only when males mount females and display courtship behaviours, including up and down movements of their antennae and forelegs [36]. That is, R. pedestris males cannot coerce females to mate. In our observation, when females are reluctant to mate, they actively kick males with their hind legs, preventing males from mounting them and displaying courtship signals. Additionally, we found that there were no differences in copulation frequency or duration between monogamous and polyandrous females and that males in the polyandry treatment experienced copulation frequencies and durations that were half those of males in the monogamy treatment. This result indicates that R. pedestris females that live with multiple potential mates refuse to engage in prolonged mating with a single male. Thus, as R. pedestris females control mating decisions, female copulation frequency is not a function of the number of potential mates, resulting in the lack of differences in group-level nonlinear reproductive ageing patterns between females in the monogamy and polyandry treatments.

Despite the lack of differences in group-level reproductive ageing patterns between treatments, polyandry-treatment females exhibited significant among-individual variation in their nonlinear reproductive ageing patterns, while monogamy-treatment females did not. One explanation for this difference is that the increase in the number of potential mates did not affect female copulation frequency at the group-level but increased the among-individual variation in female copulation frequency. That is, females might vary in reproductive strategies (e.g., choosy versus indiscriminate mating behaviour) in response to increased mate availability [48, 49]; this variation would lead to increased individual differences in nonlinear reproductive ageing patterns as well as in life-history strategies. Theoretically, females make flexible reproductive decisions when they can assess demographic conditions (e.g., mate availability) and evaluate the quality of potential mates [48, 49]. R. pedestris females prefer males that have longer hind legs and produce more rapid courtship tapping [50], indicating that they assess the quality of potential mates. This preference also implies that R. pedestris females will vary in their copulation frequency and reproductive strategies when multiple mates are available, thus resulting in greater individual differences in reproductive ageing patterns. For example, in the polyandry treatment that provides the opportunity to mate with multiple available males, some females may increase copulation frequency with multiple males early in life (i.e., increased investment in early-life reproduction) and experience rapid reproductive ageing, whereas other females may be choosy, maintaining moderate copulation frequency throughout their lifetime and experiencing slow reproductive ageing. In contrast, in the monogamy treatment where only a single male is available, females could not be choosy. Although there was an extra male in the monogamy treatment, he was unavailable for copulation. Thus, females were not in direct contact with him, were unable to precisely assess his quality and could not be choosy. We also found that female copulation frequency did not differ between the monogamy and polyandry treatments, suggesting that monogamy-treatment females were less choosy (or not choosy) than polyandry-treatment females. Therefore, all the monogamy-treatment females indiscriminately allowed male mating attempts and showed similar negative quadratic reproductive ageing patterns among individuals.

Therefore, in insect species in which females control mating decisions, increased mate availability facilitates variation in female reproductive strategies, leading to an increase in the extent of individual differences in nonlinear reproductive ageing patterns. However, the opposite is expected in insect species in which males obtain copulations through coercion. In such species, more females are predicted to experience multiple copulations as the number of males increases, potentially decreasing individual differences in copulation frequency as well as in reproductive ageing patterns in females. Thus, future studies should determine how species-specific mating systems (e.g., which sex controls mating decisions) interact with mate availability to influence the extent of individual differences in reproductive ageing patterns as well as group-level reproductive ageing patterns.

Our results also suggest that social environment factors, such as the sex ratio, affect not only group-level female reproductive ageing patterns but also the extent of among-individual variation in female reproductive ageing patterns in insects. As the sex ratio is known to affect the cost of early-life reproduction as well as age-specific mortality [51], it may also alter reproductive ageing patterns (e.g., [52]). In conditions with a male-biased sex ratio, strong male–male competition may enhance courtship and postcopulatory guarding efforts in males [53]; however, the increased rates of male harassment and copulations may harm females [54, 55]. Thus, under a male-biased sex ratio, increased reproductive costs – for both males and females – are predicted to lead to increased investment in early-life reproduction, reduced longevity and faster reproductive ageing. For example, in the field cricket G. campestris, male calling efforts declined with age in groups with a balanced sex ratio but did not decline in groups with a female-biased sex ratio [52]. Moreover, the sex ratio is expected to affect the extent of among-individual variation in female reproductive ageing patterns, which might also be dependent upon which sex controls copulation. In insect species in which females control copulation, a male-biased sex ratio increases mate availability for females, enabling them to be choosy [48, 49] and vary their reproductive strategies. Thus, a male-biased sex ratio can increase individual differences in the reproductive ageing patterns of females in species where females control mating. In contrast, in insect species in which males control copulation, a male-biased sex ratio forces all females to experience high copulation frequency and thus decreases individual differences in the reproductive ageing patterns of females. For example, in the green-veined white butterfly (Pieris napi), males cannot coerce females to mate; thus, females exhibit among-individual variation in mating frequency even with a male-biased sex ratio [56]. This variation might lead to individual differences in life-history strategies and reproductive ageing patterns in females.

In addition to the social environment, (early or current) environmental quality is expected to influence the extent of variation in individual- and group-level patterns of reproductive ageing in insects. Environmental effects on individual or genetic variation in ageing have rarely been studied in vertebrates (but see [57]), and, to date, there have been no relevant studies on invertebrates such as insects. However, there are several predictions regarding the effects of the environment. First, individual differences in reproductive ageing patterns can be larger in high-quality environments than in low-quality environments. Individuals in high-quality environments may vary their life-history strategies according to their physiological state, which would increase individual differences in reproductive ageing patterns. In contrast, in low-quality environments, all individuals may delay reproduction, thus decreasing individual differences in reproductive ageing patterns. However, the opposite is also expected. High-quality environments may increase the reproductive ageing of all individuals (the live-fast die-young hypothesis, [58]) or decrease the reproductive ageing of all individuals (the silver spoon hypothesis, [59]), leading to similar reproductive ageing patterns among individuals. Moreover, in low-quality environments, some individuals may increase early-life reproductive investment and experience fast reproductive ageing, whereas others may delay reproduction and wait for resources to become plentiful; such discrepancies result in increases in the extent of individual differences in reproductive ageing patterns. For example, in three-spined sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus), the throat colour of males (red; a sexual signal) changes with age; no significant genetic variation in colouration-indicated ageing was found in males who experienced warm winters (a high-quality environment) in their juvenile stage, whereas males who experienced temperature regimes equivalent to those in the wild over the winter (a low-quality environment) exhibited genetic variation in colouration-indicated ageing [57]. In the green-veined white butterfly (P. napi) that we mentioned above, individual differences in female mating frequency were suggested to stem from unpredictable weather conditions [56]. These findings may imply that unfavourable environments, such as unpredictable or unfavourable weather conditions, increase individual differences in reproductive ageing patterns as well as in the timing of peak reproductive investment. A meta-analysis also found mixed results concerning the effect of environmental quality on the genetic (co)variance of traits [58]; thus, the influence of the environment on genetic or individual variance in age-related plasticity, such as reproductive ageing patterns, is also expected to be species specific. Future studies need to assess how genetic or individual variation in reproductive ageing patterns, as well as group-level reproductive ageing patterns, is influenced by environmental changes.

In the present study, we demonstrated that group-level reproductive ageing patterns in R. pedestris females did not change but that females exhibited individual differences in their patterns of reproductive ageing with increases in the number of potential mates. Previous studies have assessed the relationship between ageing and the social environment at the group level (reviewed in [15]). Here, we provide the first evidence that changes in the social environment (e.g., the number of potential mates) can alter the extent of individual variation in reproductive ageing patterns. Although individual variation in reproductive ageing patterns can be shaped by variation in the developmental (micro)environment of individuals (e.g., brood size) [16], we further suggest that the extent of individual variation in reproductive ageing patterns depends on current environmental conditions, which all individuals experience. As individual-level reproductive ageing patterns reflect life-history strategies, studying environmental influences on individual differences in reproductive ageing patterns can enhance our understanding of the evolution of life-history strategies in response to changing environments [60, 61]. Our results also suggest that the effect of the social environment on individual differences in reproductive ageing patterns depends on which sex controls copulation. Therefore, the next step in this line of research is to assess how species-specific mating systems (i.e., the sex that controls mating) and the social environment interact to shape group- and individual-level reproductive ageing patterns, thereby providing a better understanding of plasticity in life-history strategies in both vertebrates and invertebrates.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Shefferson RP, Jones OR, Salguero-Gómez R. The evolution of senescence in the tree of life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2017.

Nussey DH, Froy H, Lemaitre JF, Gaillard JM, Austad SN. Senescence in natural populations of animals: Widespread evidence and its implications for bio-gerontology. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:214–25.

Jones OR, Scheuerlein A, Salguero-Gómez R, Camarda CG, Schaible R, Casper BB, et al. Diversity of ageing across the tree of life. Nature. 2014;505:169–73.

Zajitschek F, Zajitschek S, Bonduriansky R. Senescence in wild insects: Key questions and challenges. Funct Ecol. 2020;34:26–37.

Kirkwood TBL. Evolution of ageing. Nature. 1977;270:301–4.

Kirkwood TBL, Holliday R. The Evolution of ageing and longevity. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 1979;205:531–46.

Kirkwood TBL, Rose MR. Evolution of senescence: late survival sacrificed for reproduction. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 1991;332:15–24.

Stearns SC. Life history evolution: successes, limitations, and prospects. Naturwissenschaften. 2000;87:476–86.

Lemaître JF, Berger V, Bonenfant C, Douhard M, Gamelon M, Plard F, Gaillard JM. Early-late life trade-offs and the evolution of ageing in the wild. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2015;282:20150209.

Wheeler D. The role of nourishment in oogenesis. Annu Rev Entomol. 1996;41(1):407–38.

Wigglesworth VB. Nutrition and reproduction in insects. Proc Nutri Soc. 1960;19(1):18–23.

Reinhardt K, Anthes N, Lange R. Copulatory wounding and traumatic insemination. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7(5):1–26.

Lange R, Reinhardt K, Michiels NK, Anthes N. Functions, diversity, and evolution of traumatic mating. Biol Rev. 2013;88(3):585–601.

Lemaître JF, Gaillard JM. Reproductive senescence: new perspectives in the wild. Biol Rev. 2017;92:2182–99.

Cooper EB, Kruuk LEB. Ageing with a silver-spoon: a meta-analysis of the effect of developmental environment on senescence. Evol Lett. 2018;2:460–71.

Spagopoulou F, Teplitsky C, Lind MI, Chantepie S, Gustafsson L, Maklakov AA. Silver-spoon upbringing improves early-life fitness but promotes reproductive ageing in a wild bird. Ecol Lett. 2020;Vol. 23:23;994–1002.

Snook R. The evolution of polyandry. In: Shuker D, Simmons L, editors. The evolution of insect mating systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014. pp. 159–80.

Arnqvist G, Nilsson T. The evolution of polyandry: multiple mating and female fitness in insects. Anim Behav. 2000;60:145–64.

Slatyer RA, Jennions MD, Backwell PRY. Polyandry occurs because females initially trade sex for protection. Anim Behav. 2012;83:1203–6.

Travers LM, Garcia-Gonzalez F, Simmons LW. Live fast die young life history in females: Evolutionary trade-off between early life mating and lifespan in female Drosophila melanogaster. Sci Rep. 2015;5:1–7.

van de Pol M, Verhulst S. Age-Dependent Traits: a new statistical model to separate within-and between-Individual effects. Am Nat. 2006;167:766–73.

Lauer MJ, Sih A, Krupa JJ. Male density, female density and inter-sexual conflict in a stream-dwelling insect. Anim Behav. 1996;Vol. 52:52:929–39.

Cordero A, Andrés J. Male coercion and convenience polyandry in a calopterygid damselfly. J Insect Sci. 2002. https://doi.org/10.1093/jis/2.1.14.

Ridley M. The control and frequency of mating in insects. Funct Ecol. 1990;4:75–84.

Wolf M, van Doorn GS, Leimar O, Weissing FJ. Life-history trade-offs favour the evolution of animal personalities. Nature. 2007;447:581–84.

Biro PA, Stamps JA. Are animal personality traits linked to life-history productivity? Trends Ecol Evol. 2008;23:361–8.

Laskowski KL, Moiron M, Niemelä PT. Integrating behavior in life-history theory: allocation versus acquisition? Trends Ecol Evol. 2021;36:132–8.

Paaby AB, Rockman MV. Cryptic genetic variation: evolution’s hidden substrate. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:247–58.

Brommer JE, Rattiste K, Wilson A. The rate of ageing in a long-lived bird is not heritable. Heredity. 2010;104:363–70.

Chantepie S, Robert A, Sorci G, Hingrat Y, Charmantier A, Leveque G, Lacroix F, Teplitsky C. Quantitative genetics of the aging of reproductive traits in the houbara bustard. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0133140.

Han CS, Yang G. Reproductive aging and pace-of-life syndromes: more active females age faster. Behav Ecol. 2021;32:926–31.

Lim UT. Occurrence and Control Method of Riptortus pedestris (Hemiptera: Alydidae): Korean perspectives. Korean J Appl Entomol. 2013;52:437–48.

Kim S, Lim UT. Seasonal occurrence pattern and within-plant egg distribution of bean bug, Riptortus pedestris (Fabricius) (Hemiptera: Alydidae), and its egg parasitoids in soybean fields. Appl Entomol Zool. 2010;45:457–64.

Bae S, Kim HJ, Park CG, Lee GH, Park ST. The development and oviposition of bean bug, Riptortus clavatus Thunberg (Hemiptera: Alydidae) at temperature conditions. Korean J Appl Entomol. 2005;44:325–30.

Sakurai T. Multiple Mating and Its Effect on Female Reproductive Output in the Bean Bug Riptortus clavatus (Heteroptera: Alydidae). Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1996;89:481–5.

Numata H, Matsui N, Hidaka T. Mating behavior of the bean bug, Riptortus clavatus Thenberg (Heteroptera: Coreidae): behavioral sequence and the role of olfaction. Appl Entomol Zool. 1986;21:119–25.

Lauer MJ, Sih A, Krupa JJ. Male density, female density and inter-sexual conflict in a stream-dwelling insect. Anim Behav. 1996;52:929–39.

Holveck MJ, Gauthier AL, Nieberding CM. Dense, small and male-biased cages exacerbate male-male competition and reduce female choosiness in Bicyclus anynana. Anim Behav. 2015;104:229–45.

Wey TW, Chang AT, Montiglio PO, Fogarty S, Sih A. Linking short-term behavior and personalities to feeding and mating rates in female water striders. Behav Ecol. 2015;26:1196–202.

Monier M, Nöbel S, Isabel G, Danchin E. Effects of a sex ratio gradient on female mate-copying and choosiness in Drosophila melanogaster. Curr Zool. 2018;64:251–8.

Pompilio L, Franco MG, Chisari LB, Manrique G. Female choosiness and mating opportunities in the blood-sucking bug Rhodnius prolixus. Behaviour. 2016;153:1863–78.

De Simone GA, Pompilio L, Manrique G. The effects of a male audience on male and female mating behaviour in the blood-sucking bug Rhodnius prolixus. Neotrop Entomol. 2022;51:212–20.

Suzaki Y, Katsuki M, Okada K. Attractive males produce high-quality daughters in the bean bug Riptortus pedestris. Entomol Exp Appl. 2018;166:17–23.

Westneat DF, Araya-Ajoy YG, Allegue H, Class B, Dingemanse N, Dochtermann NA, et al. Collision between biological process and statistical analysis revealed by mean centring. J Anim Ecol. 2020;89(12):2813–24.

Fay R, Martin J, Plard F. Distinguishing within- from between-individual effects: How to use the within-individual centring method for quadratic patterns. J Anim Ecol. 2022;91:8–19.

Self SG, Liang KY. Asymptotic properties of maximum likelihood estimators and likelihood ratio tests under nonstandard conditions. J Am Stat Assoc. 1987;82:605–10.

Visscher PM. A note on the asymptotic distribution of likelihood ratio tests to test variance components. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9:490–5.

Gowaty PA, Hubbell SP. Reproductive decisions under ecological constraints: it’s about time. PNAS. 2009;106:10017–24.

Ah-King M, Gowaty PA. A conceptual review of mate choice: stochastic demography, within-sex phenotypic plasticity, and individual flexibility. Ecol Evol. 2016;6:4607–42.

Suzaki Y, Katsuki M, Miyatake T, Okada Y. Male courtship behavior and weapon trait as indicators of indirect benefit in the bean bug, Riptortus pedestris. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e83278.

Adler MI, Bonduriansky R. The dissimilar costs of love and war: Age-specific mortality as a function of the operational sex ratio. J Evol Biol. 2011;24:1169–77.

Rodríguez-Muñoz R, Boonekamp JJ, Fisher D, Hopwood P, Tregenza T. Slower senescence in a wild insect population in years with a more female-biased sex ratio. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2019;286:20190286.

Weir LK, Grant JWA, Hutchings JA. The influence of operational sex ratio on the intensity of competition for mates. Am Nat. 2011;177:167–76.

Wigby S, Chapman T. Female resistance to male harm evolves in response to manipulation pf sexual conflict. Evolution. 2004;58:1028–37.

Holland B, Rice WR. Experimental removal of sexual selection reverses intersexual antagonistic coevolution and removes a reproductive load. PNAS. 1999;96:5083–88.

Välimäki P, Kaitala A, Kokko H. Temporal patterns in reproduction may explain variation in mating frequencies in the green-veined white butterfly Pieris napi. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2006;61:99–107.

Kim SY, Metcalfe NB, Velando A. A benign juvenile environment reduces the strength of antagonistic pleiotropy and genetic variation in the rate of senescence. J Anim Ecol. 2016;85:705–14.

Wood CW, Brodie ED. Environmental effects on the structure of the G-matrix. Evolution. 2015;69:2927–40.

Grafen A. On the uses of data on lifetime reproductive success. In: Clutton-Brock TH, editor. Reproductive success. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1988. p. 454–63.

Montiglio PO, Dammhahn M, Dubuc Messier G, Réale D. The pace-of-life syndrome revisited: the role of ecological conditions and natural history on the slow-fast continuum. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2018;72:1–9.

Hämäläinen AM, Guenther A, Patrick SC, Schuett W. Environmental effects on the covariation among pace-of-life traits. Ethology. 2021;127:32–44.

Acknowledgements

We thank three anonymous reviewers who improved earlier versions of the manuscript.

Funding

YHP is funded by a Student Research Grant from the Animal Behavior Society (ABS). CSH is funded by a Basic Science Research Program grant through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2022R1C1C1004303) and a grant from Kyung Hee University in 2021 (KHU-20210147).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CSH conceived and designed the study; YHP, DS, and CSH collected the data; YHP and CSH analysed the data and led the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave their final approval for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study did not include research with ethical considerations because experiments on insects do not require approval from the Ethics Committee of Kyung Hee University, Korea.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, Y.H., Shin, D. & Han, C.S. Polyandrous females but not monogamous females vary in reproductive ageing patterns in the bean bug Riptortus pedestris. BMC Ecol Evo 22, 115 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-022-02070-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-022-02070-1