Abstract

Background

The Fujiwara-kyo Osteoporosis Risk in Men (FORMEN) study was launched to investigate risk factors for osteoporotic fractures, interactions of osteoporosis with other non-communicable chronic diseases, and effects of fracture on QOL and mortality.

Methods

FORMEN baseline study participants (in 2007 and 2008) included 2012 community-dwelling men (aged 65–93 years) in Nara prefecture, Japan. Clinical follow-up surveys were conducted 5 and 10 years after the baseline survey, and 1539 and 906 men completed them, respectively. Supplemental mail, telephone, and visit surveys were conducted with non-participants to obtain outcome information. Survival and fracture outcomes were determined for 2006 men, with 566 deaths identified and 1233 men remaining in the cohort at 10-year follow-up.

Comments

The baseline survey covered a wide range of bone health-related indices including bone mineral density, trabecular microarchitecture assessment, vertebral imaging for detecting vertebral fractures, and biochemical markers of bone turnover, as well as comprehensive geriatric assessment items. Follow-up surveys were conducted to obtain outcomes including osteoporotic fracture, cardiovascular diseases, initiation of long-term care, and mortality. A complete list of publications relating to the FORMEN study can be found at https://www.med.kindai.ac.jp/pubheal/FORMEN/Publications.html.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In aging societies, osteoporotic fracture is a significant public health and economic burden not only for women but also for men. The incidence of hip fracture, the most serious type of osteoporotic fracture, is increasing and is projected to reach 13 million in 2050, with 31% of these (approximately 4 million) occurring in men [1]. It is well established that the incidence of hip fracture is higher in Caucasians than in Asians [2], but Asians will account for 45% of hip fractures globally in 2050 given the dramatic increase in elderly populations in Asia [1]. In Japan, nationwide surveys on the incidence of hip fracture have been conducted on six occasions since 1987 [3]. There were 176,000 estimated incident hip fractures in 2012 (triple the number from 1987), of which 22% occurred in men [3]. In addition, recent age-standardized incidence rates of hip fracture in men are increasing in Japan, while corresponding rates in women are stable [4]. This increasing trend highlights the need to establish a comprehensive strategy to prevent and manage osteoporosis in men, both on national and global levels.

Despite the substantial impact of osteoporosis on men, information on this topic is lacking, particularly in Asia. Only a few prospective cohort studies have been published on determinants of osteoporotic fracture in Hong Kong Chinese men [5] and Japanese men [6,7,8]. However, the sample size of these studies did not exceed 800, which is too low to meaningfully extract determinants [6,7,8]. Similarly, comprehensive geriatric assessments for evaluating risk factors of osteoporotic fracture are lacking. Such data are required to design rational clinical and preventive measures against osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures. Against this backdrop, the Fujiwara-kyo Osteoporosis Risk in Men (FORMEN) study (Primary Investigator: Masayuki Iki), a large-scale community-based single-center prospective cohort study for elderly Japanese men, was conducted to address the following questions:

-

1.

Which lifestyle and medical factors are associated with fracture risk in men?

-

2.

Do bone turnover markers and other bone-related indices enhance the predictive value of bone density and other clinical risk factors for fracture risk in men?

-

3.

To what extent do fractures increase the risk of being dependent on care provided from long-term care insurance (LCI) and affect quality of life (QOL) in men?

-

4.

Do existing vertebral fractures and incident osteoporotic fractures increase the risk of death in men?

-

5.

Are osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures associated with the incidence or progression of non-communicable diseases including cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and diabetes mellitus?

Methods/design

Study setting and participants

The FORMEN study is an ancillary study of a larger prospective cohort study, the Cohort Study for Functioning Capacity and Quality of Life in Elderly Japanese (Primary Investigator: Norio Kurumatani), referred to as the “Fujiwara-kyo study” after the study area where the first capital of Japan (Fujiwara-kyo) was established in 694 AD. The Fujiwara-kyo study aims to provide a scientific basis for a comprehensive strategy to prevent frailty, increase the number of healthy life years, and promote the functioning capacity and quality of life of elderly men and women in Japan.

To achieve these aims, participants should be representative of elderly men and women who live independently in a community and can participate in various preventive activities conducted by their municipalities. Thus, inclusion criteria for participants of the Fujiwara-kyo study are as follows:

-

(1)

Aged 65 years or older at baseline,

-

(2)

Living in their homes in the cities of Kashihara, Nara, Yamato-Kooriyama, and Kashiba,

-

(3)

Able to walk without the assistance of another person,

-

(4)

Able to provide self-reported information, and

-

(5)

Able to understand and provide written informed consent.

The FORMEN study focuses on bone health of male participants of the Fujiwara-kyo study. Most non-skeletal measurements and interviews were conducted in the Fujiwara-kyo study and form a comprehensive geriatric and gerontologic basis for the FORMEN study to evaluate risk factors of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures in elderly men.

The sample size necessary for the FORMEN study was set at 2000. This number is needed to obtain significant results from logistic regression analysis with a two-tailed level of significance of 5% and a statistical power of 80%, when a risk factor for fracture is assumed to exist in 20% of participants of the FORMEN baseline study and to increase a background fracture risk of 1% per year by 75% during the 5-year follow-up period.

Written informed consent was obtained from each subject before participating in the study. The protocol of the FORMEN study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kindai University Faculty of Medicine (Approval number 19-32, 29-162).

Study design and timeline

Baseline clinical surveys of the Fujiwara-kyo study were conducted in 2007 and 2008. Clinical follow-up surveys, which included similar study items as the baseline survey as well as items identifying outcomes, were conducted in 2012–2013 and 2017–2019. Supplemental mail and telephone surveys and a visit survey were conducted for those who did not participate in the clinical surveys in order to identify the incidence of outcomes.

Measurements

The baseline survey of the FORMEN study covered a wide range of bone health-related indices such as BMD measurements, trabecular microarchitecture assessment, X-ray absorptiometric imaging of the spine for detecting vertebral fractures, and biochemical markers of bone turnover, as well as comprehensive geriatric assessment items obtained in the Fujiwara-kyo study. Follow-up surveys were designed to identify outcomes such as the incidence of vertebral fractures and clinical fractures, change in BMD, LCI benefits, and death. Measurements made in the FORMEN study are shown in Table 1.

Assessment of predictors

Bone mass measurements

L1 to L4 vertebrae and the proximal femur were scanned in posteroanterior projection with a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scanner (QDR4500A, Hologic Inc., Bedford, MA, USA) installed in a mobile test room. BMD of the spine and femoral neck, trochanteric, intertrochanteric, and Ward’s triangle regions were obtained [9].

Prevalent vertebral deformity assessment

Thoracolumbar vertebrae were imaged by single-energy X-ray absorptiometry (SXA) (T4 through L4) at baseline and each of the follow-up surveys by certified radiological technologists using the same scanner that was used to measure BMD. Vertebral deformities were diagnosed at baseline according to Genant’s semiquantitative assessment method [10].

Trabecular bone microarchitecture assessment

Spine DXA images archived at baseline were further analyzed by the TBS iNsight software (Version 2.1, Med-Imaps, Bordeaux, France) to obtain the trabecular bone score (TBS). TBS is a texture parameter that quantifies local variations in gray level distribution of DXA images. TBS is not a direct physical measure of bone microarchitecture but is highly correlated with its three-dimensional parameters [11, 12].

Bone turnover markers and other laboratory measurements

In each survey of the FORMEN study, venous blood samples were drawn from all participants on their visits from 09:00 to 14:00 after at least a 7-h fast. Serum samples were stored at −80°C until use.

As markers of bone formation, intact molecule of osteocalcin (OC) was measured by a two-site immunoradiometric assay (IRMA) (BGP IRMA kit; Mitsubishi Kagaku Iatron, Tokyo, Japan), and type I procollagen N-terminal propeptide by a radioimmunoassay (Procollagen Intact OINO; Orion Diagnostica, Espoo, Finland). As bone resorption markers, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase isoenzyme 5b was measured by a fragment-absorbed immunocapture enzyme assay (Osteolinks-TRAP-5b; Nitto Boseki, Kooriyama, Japan), and type I collagen C-terminal telopeptide by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Serum CrossLaps; Immunodiagnostic Systems Ltd., Boldon, UK).

Other bone-related measurements

Serum undercarboxylated OC (ucOC) was measured as a marker for vitamin K sufficiency by an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Picolumi ucOC; Sanko Junyaku Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), serum pentosidine levels by competitive ELISA kits (FSK PEN ELISA kit; Fushimi Pharmaceutical Co., Marugame, Japan), endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation end products (esRAGE) by ELISA kits (B-Bridge esRAGE ELISA kit; B-Bridge International, Mountain View, CA, USA), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels by nephelometry (N-Latex CRP II; Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc., Deerfield, IL, USA).

Assessment of outcomes

Incidence of morphometric vertebral fractures

An incident vertebral fracture was diagnosed morphometrically based on SXA images of the spine when the anterior, central, or posterior height of a vertebra are reduced by 20% or more on follow-up images compared to baseline and when the vertebra also satisfies the definition of grade 2 or 3 fracture by Genant’s method [10].

Incidence of clinical fractures

The time of a fracture event, the skeletal site of fracture, the situation in which the fracture occurred, and use of radiographs for forming the diagnosis of fracture by a physician were obtained during interviews at each follow-up survey. Supplemental mail and telephone surveys were conducted just after the follow-up surveys to obtain the same information from non-participants. Fragility fracture was defined as a fracture that occurred without strong external force, caused pain, and was diagnosed by a physician with radiographic examination.

The above method was validated using 21 incident fractures identified during the first 2 years of follow-up. Of these, 19 participants provided consent to contact the attending surgeon in order to confirm the occurrence, date, and skeletal site of fractures. All surgeons responded to our inquiries and confirmed the occurrence of all self-reported fractures and that differences between the self-reported date and the real date of fracture events were within 6 months. Self-reported fracture sites seldom differed from the correct sites. We concluded that the false-positive rate for fracture detection using the present method was extremely low and that errors in fracture dates and skeletal sites would be within an acceptable range.

Ultrasonography at the carotid artery and pulse wave velocity measurement

Ultrasonographic examination of carotid arteries was performed with participants in the supine position using high-resolution B-mode ultrasonography with a 7.5 MHz linear probe (SSA-660A Xrio, Thoshiba Medical Systems Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Intima-media thickness of the far wall at the carotid bifurcation (BIF-IMT) was measured in four views, i.e., longitudinal and transverse sections of the bifurcation of the right and left arteries, and the maximum value of the four wall measurements was adopted as the BIF-IMT value according to the Guidelines for Ultrasonic Assessment of Carotid Artery Disease by the Japan Academy of Neurosonology [13].

Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV) was measured using a volume plethysmographic apparatus (Form PWV/ABI; Fukuda Colin Co., Ltd. Tokyo, Japan). Participants were examined while resting in a supine position with the measurement device set to record baPWV. Both the brachium and ankle were wrapped with cuffs connected to plethysmographic sensors in order to determine brachial and post-tibial arterial pressure waveforms. baPWV was calculated as the difference (cm) between the path lengths from the heart to the brachium and from the heart to the ankle divided by the traveling time delay (s) of the pulse wave detected at the ankle compared with that at the brachium.

Identification of deaths

Participant deaths that occurred from baseline to the end of March 2019 were identified through supplemental mail and telephone surveys for non-participants in the clinical follow-up surveys and inquiries to the municipal resident registry for non-respondents to the supplemental surveys. We obtained the dates but not the causes of deaths since the cause of death was not included in the resident registry.

Key findings

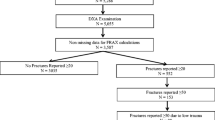

A flow diagram of participant selection is shown in Fig. 1. Of the 4427 participants of the Fujiwara-kyo study, 2174 were men and were invited to participate in the FORMEN study. Of these, 2012 completed the baseline survey. Among them, 1556 men (77.3%) participated in at least one clinical follow-up survey, and 450 additional men responded to the supplemental surveys. Consequently, we identified 220 participants with incident fractures and 566 deaths from baseline to the end of March 2019.

Table 2 shows a comparison of baseline characteristics between participants and non-participants of the clinical follow-up surveys. Non-participants were significantly older; shorter in height; lighter in weight; consumed less energy, less calcium, and less vitamin K; had lower bone mineral density (BMD) at the hip and femoral neck; and had higher values of glycemic indices, cystatin-c, and c-reactive protein than participants. More non-participants were current smokers than participants, while fewer non-participants were habitual drinkers than participants. History or present involvement of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) was significantly higher in non-participants than participants. Although clinical data for non-participants of the follow-up surveys were lacking, outcome data including clinical fractures, LCT benefits, and deaths were available for a total of 2006 men (99.7% of all participants at baseline).

We explored risk factors for low BMD by cross-sectional analyses using data from the FORMEN baseline study. Patients with end-stage kidney disease or predialysis renal failure have been reported to exhibit decreased BMD [14, 15]. However, we found that higher serum creatinine levels were associated with higher BMD at the femoral neck in participants of the FORMEN study, while cystatin-c levels were not [16]. Creatinine may not be an appropriate index to evaluate the renal effect on BMD in people with normal to moderate impairment of renal function, since greater muscle mass results in higher levels of serum creatinine and BMD. With regard to lifestyle factors, we found that current smoking [17], habitual drinkers with an ethanol intake of more than 60 g/day [18], no intake of fermented soybean product (natto) [19], and low intake of vitamin K [19] and milk [20] were significantly associated with low BMD.

We also explored risk factors for fracture. Patients with T2DM reportedly have increased BMD but an elevated risk of fracture [21]. A similar result was observed in the FORMEN study [22], but fracture risk in patients with T2DM was greater and appeared at an earlier stage of T2DM than reported in a meta-analysis of Caucasian populations [21], suggesting a potential ethnic difference in susceptibility of bone strength to hyperglycemia. One of the causes of increased fracture risk in T2DM patients may be an increase in retention of advanced glycated end-product (AGE) in bone tissue [23]. We found that esRAGE, a decoy receptor for AGE, was associated with a lower risk of osteoporotic fracture, while pentosidine, an AGE, was associated with a higher risk [24]. In addition, patients with T2DM had a lower TBS than those without [25]. Thus, T2DM may increase fracture risk through the retention of AGE and deterioration of trabecular bone microarchitecture.

Gastric cancer is one of the most common cancers in Japan, and 70% of patients with gastric cancer are indicated for gastrectomy. FORMEN participants with a history of gastrectomy showed a three-fold higher risk of osteoporotic fracture than those without [26]. This increase in risk persisted for more than 20 years after gastrectomy, regardless of the reason for undergoing the procedure. We found that participants with lower serum uric acid levels also had an increased risk of vertebral fracture than those with higher levels [27]. This suggests that excessive treatment of patients with gout by uric acid-lowering medications may increase the risk of vertebral fracture. FRAX®, a fracture risk assessment tool, is increasingly being used in clinical settings, but its predictive ability is not high [28]. In the FORMEN study, a lower TBS was related to a higher risk of major osteoporotic fracture independently of the risk predicted by FRAX® score [29], suggesting that TBS may improve the predictive ability of FRAX® for fracture risk [30].

OC, a biochemical marker for bone formation, is a hormone that regulates energy and glucose metabolism in mice, and its active form is ucOC [31]. Serum ucOC levels were inversely associated with glycemic indices, and patients with T2DM showed significantly lower ucOC levels than those without [32]. These findings suggest that ucOC may function in a similar manner in humans as in mice.

Patients with hip fracture and clinically manifested vertebral fracture have an increased risk of mortality [33], but it is unclear whether fractures increase the risk of death via frailty, which is known to increase the risk of fracture and death. In the FORMEN study, participants with incident fractures showed a three-fold higher risk of death than those without fracture, and this increased risk was independent of frailty indices, including physical performance test results [34].

A complete list of publications relating to the FORMEN study can be found at https://www.med.kindai.ac.jp/pubheal/FORMEN/Publications.html.

Discussion

The FORMEN study has some strengths over previous studies. First, the sample size of the FORMEN study is the largest of this kind in Japan. Thus, risk factors of vertebral and osteoporotic fractures can be evaluated with robust statistical power. Second, the FORMEN study comprehensively covered skeletal measures relevant to osteoporosis, including vertebral fracture assessment and TBS, as well as conventional BMD measurements. Third, biochemical markers of bone turnover in sera were measured for all participants, with remaining sera stored at −80°C for measurements of new markers. Fourth, the FORMEN study comprehensively evaluated potential risk factors of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures based on geriatric and gerontologic assessments. Finally, there is no inter-center variation due to the single-center study design.

The FORMEN study also has potential limitations worth noting. First, participants were not randomly selected. Thus, caution must be exercised when generalizing the results. Second, although large, the sample size of the FORMEN study may still be insufficient to assess risk factors for fracture with relatively low risk or low prevalence. Third, BMD measurements did not include whole body BMD or volumetric BMD obtained by quantitative computed tomography. Fourth, vertebral deformity detected with SXA images might underestimate the prevalence of vertebral fractures compared to diagnosis with conventional radiographs since concave type or endplate fractures may have been missed [35]. Fifth, we did not cross-check all self-reported fracture events with data from medical records, although our validation study and previous studies indicated that self-reported data are relatively accurate [36, 37]. Finally, a survey of causes of death is not included in the study protocol and thus was not performed.

In conclusion, the prospective cohort data from the FORMEN study will provide reliable evidence regarding the risk factors of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures and establish a comprehensive strategy to promote bone health in men.

Availability of data and materials

The FORMEN dataset is not freely available, but the Study Group has collaborated with several other groups to share study data and encourages new collaborations. Potential collaborators are invited to contact the Secretary General (Yuki Fujita, PhD, pbl-h@med.kindai.ac.jp) at the administrative office of the FORMEN Study Group at the Department of Public Health, Kindai University Faculty of Medicine, Osaka-Sayama, Osaka, Japan.

Abbreviations

- AGE:

-

Advanced glycated end-product

- BIF:

-

Carotid bifurcation

- baPWV:

-

Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity

- BMD:

-

Bone mineral density

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular diseases

- DXA:

-

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- esRAGE:

-

Endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation end products

- FORMEN:

-

Fujiwara-kyo Osteoporosis Risk in Men

- IRMA:

-

Immunoradiometric assay

- IMT:

-

Intima-media thickness

- LCI:

-

Long-term care insurance

- OC:

-

Osteocalcin

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- SXA:

-

Single-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TBS:

-

Trabecular bone score

- ucOC:

-

Undercarboxylated osteocalcin

References

Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA. World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 1997;7(5):407–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00004148.

Yoshimura N, Suzuki T, Hosoi T, Orimo H. Epidemiology of hip fracture in Japan: incidence and risk factors. J Bone Miner Metab. 2005;23(Suppl):78–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03026328.

Orimo H, Yaegashi Y, Hosoi T, Fukushima Y, Onoda T, Hashimoto T, et al. Hip fracture incidence in Japan: estimates of new patients in 2012 and 25-year trends. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(5):1777–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3464-8.

Tamaki J, Fujimori K, Ikehara S, Kamiya K, Nakatoh S, Okimoto N, et al. Estimates of hip fracture incidence in Japan using the National Health Insurance Claim Database in 2012-2015. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(5):975–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-019-04844-8.

Lau EM, Leung PC, Kwok T, Woo J, Lynn H, Orwoll E, et al. The determinants of bone mineral density in Chinese men--results from Mr. Os (Hong Kong), the first cohort study on osteoporosis in Asian men. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(2):297–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-005-2019-9.

Yoshimura N, Kinoshita H, Takijiri T, Oka H, Muraki S, Mabuchi A, et al. Association between height loss and bone loss, cumulative incidence of vertebral fractures and future quality of life: the Miyama study. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(1):21–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0474-1.

Yoshimura N, Kasamatsu T, Sakata K, Hashimoto T, Cooper C. The relationship between endogenous estrogen, sex hormone-binding globulin, and bone loss in female residents of a rural Japanese community: the Taiji Study. J Bone Miner Metab. 2002;20(5):303–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007740200044.

Fujiwara S, Kasagi F, Masunari N, Naito K, Suzuki G, Fukunaga M. Fracture prediction from bone mineral density in Japanese men and women. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(8):1547–53. https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.8.1547.

Iki M, Kagamimori S, Kagawa Y, Matsuzaki T, Yoneshima H, Marumo F. Bone mineral density of the spine, hip and distal forearm in representative samples of the Japanese female population: Japanese Population-Based Osteoporosis (JPOS) Study. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12(7):529–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001980170073.

Genant HK, Wu CY, van Kuijk C, Nevitt MC. Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8(9):1137–48.

Hans D, Barthe N, Boutroy S, Pothuaud L, Winzenrieth R, Krieg MA. Correlations between trabecular bone score, measured using anteroposterior dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry acquisition, and 3-dimensional parameters of bone microarchitecture: an experimental study on human cadaver vertebrae. J Clin Densitom. 2011;14(3):302–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocd.2011.05.005.

Silva BC, Leslie WD, Resch H, Lamy O, Lesnyak O, Binkley N, et al. Trabecular bone score: a noninvasive analytical method based upon the DXA image. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(3):518–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2176.

Nuerosonology TJCoTJAoNaTJSoEDaToGf. The Guidelines for Ultrasonic Assessment of Carotid Artery Disease, vol. 19; 2006. p. 50–69.

Alem AM, Sherrard DJ, Gillen DL, Weiss NS, Beresford SA, Heckbert SR, et al. Increased risk of hip fracture among patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2000;58(1):396–9. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00178.x.

Nickolas TL, Leonard MB, Shane E. Chronic kidney disease and bone fracture: a growing concern. Kidney Int. 2008;74(6):721–31. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2008.264.

Fujita Y, Iki M, Tamaki J, Kouda K, Yura A, Kadowaki E, et al. Renal function and bone mineral density in community-dwelling elderly Japanese men: the Fujiwara-kyo Osteoporosis Risk in Men (FORMEN) Study. Bone. 2013;56(1):61–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2013.05.004.

Tamaki J, Iki M, Fujita Y, Kouda K, Yura A, Kadowaki E, et al. Impact of smoking on bone mineral density and bone metabolism in elderly men: the Fujiwara-kyo Osteoporosis Risk in Men (FORMEN) study. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(1):133–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1238-x.

Kouda K, Iki M, Fujita Y, Tamaki J, Yura A, Kadowaki E, et al. Alcohol intake and bone status in elderly Japanese men: baseline data from the Fujiwara-kyo osteoporosis risk in men (FORMEN) study. Bone. 2011;49(2):275–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2011.04.010.

Fujita Y, Iki M, Tamaki J, Kouda K, Yura A, Kadowaki E, et al. Association between vitamin K intake from fermented soybeans, natto, and bone mineral density in elderly Japanese men: the Fujiwara-kyo Osteoporosis Risk in Men (FORMEN) study. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(2):705–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1594-1.

Sato Y, Iki M, Fujita Y, Tamaki J, Kouda K, Yura A, et al. Greater milk intake is associated with lower bone turnover, higher bone density, and higher bone microarchitecture index in a population of elderly Japanese men with relatively low dietary calcium intake: Fujiwara-kyo Osteoporosis Risk in Men (FORMEN) Study. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(5):1585–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3032-2.

Vestergaard P. Discrepancies in bone mineral density and fracture risk in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes--a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(4):427–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0253-4.

Iki M, Fujita Y, Kouda K, Yura A, Tachiki T, Tamaki J, et al. Hyperglycemic status is associated with an elevated risk of osteoporotic fracture in community-dwelling elderly Japanese men: the Fujiwara-kyo Osteoporosis Risk in Men (FORMEN) cohort study. Bone. 2019;121:100–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2019.01.005.

Saito M, Marumo K. Collagen cross-links as a determinant of bone quality: a possible explanation for bone fragility in aging, osteoporosis, and diabetes mellitus. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(2):195–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-1066-z.

Tamaki J, Kouda K, Fujita Y, Iki M, Yura A, Miura M, et al. Ratio of endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation end products to pentosidine predicts fractures in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(1):85–94. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2017-00929.

Iki M, Fujita Y, Kouda K, Yura A, Tachiki T, Tamaki J, et al. Hyperglycemia is associated with increased bone mineral density and decreased trabecular bone score in elderly Japanese men: the Fujiwara-kyo osteoporosis risk in men (FORMEN) study. Bone. 2017;105:18–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2017.08.007.

Iki M, Fujita Y, Kouda K, Yura A, Tachiki T, Tamaki J, et al. Increased risk of osteoporotic fracture in community-dwelling elderly men 20 or more years after gastrectomy: the Fujiwara-kyo Osteoporosis Risk in Men (FORMEN) Cohort Study. Bone. 2019;127:250–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2019.06.014.

Iki M, Yura A, Fujita Y, Kouda K, Tachiki T, Tamaki J, et al. Relationships between serum uric acid concentrations, uric acid lowering medications, and vertebral fracture in community-dwelling elderly Japanese men: Fujiwara-kyo Osteoporosis Risk in Men (FORMEN) Cohort Study. Bone. 2020;139:115519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2020.115519.

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, Johansson H, De Laet C, Brown J, et al. The use of clinical risk factors enhances the performance of BMD in the prediction of hip and osteoporotic fractures in men and women. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(8):1033–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0343-y.

Iki M, Fujita Y, Tamaki J, Kouda K, Yura A, Sato Y, et al. Trabecular bone score may improve FRAX(R) prediction accuracy for major osteoporotic fractures in elderly Japanese men: the Fujiwara-kyo Osteoporosis Risk in Men (FORMEN) Cohort Study. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(6):1841–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3092-3.

McCloskey EV, Oden A, Harvey NC, Leslie WD, Hans D, Johansson H, et al. A meta-analysis of trabecular bone score in fracture risk prediction and its relationship to FRAX. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31(5):940–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2734.

Lee NK, Sowa H, Hinoi E, Ferron M, Ahn JD, Confavreux C, et al. Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton. Cell. 2007;130(3):456–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.047.

Iki M, Tamaki J, Fujita Y, Kouda K, Yura A, Kadowaki E, et al. Serum undercarboxylated osteocalcin levels are inversely associated with glycemic status and insulin resistance in an elderly Japanese male population: Fujiwara-kyo Osteoporosis Risk in Men (FORMEN) Study. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(2):761–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1600-7.

Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Ensrud KC, Scott JC, Black D. Risk of mortality following clinical fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11(7):556–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001980070075.

Iki M, Fujita Y, Tamaki J, Kouda K, Yura A, Sato Y, et al. Incident fracture associated with increased risk of mortality even after adjusting for frailty status in elderly Japanese men: the Fujiwara-kyo Osteoporosis Risk in Men (FORMEN) Cohort Study. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(3):871–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3797-y.

Ferrar L, Jiang G, Clowes JA, Peel NF, Eastell R. Comparison of densitometric and radiographic vertebral fracture assessment using the algorithm-based qualitative (ABQ) method in postmenopausal women at low and high risk of fracture. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(1):103–11. https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.070902.

Ismail AA, O'Neill TW, Cockerill W, Finn JD, Cannata JB, Hoszowski K, et al. Validity of self-report of fractures: results from a prospective study in men and women across Europe. EPOS Study Group. European Prospective Osteoporosis Study Group. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11(3):248–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001980050288.

Hundrup YA, Hoidrup S, Obel EB, Rasmussen NK. The validity of self-reported fractures among Danish female nurses: comparison with fractures registered in the Danish National Hospital Register. Scand J Public Health. 2004;32(2):136–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/14034940310017490.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Fujiwara-kyo Study Group (chaired by Norio Kurumatani with Nozomi Okamoto as a secretary general), comprising Nobuko Amano, Yuki Fujita, Akihiro Harano, Kan Hazaki, Masayuki Iki, Junko Iwamoto, Akira Minematsu, Masayuki Morikawa, Keigo Saeki, Noriyuki Tanaka, Kimiko Tomioka, and Motokazu Yanagi, for providing data on non-skeletal measures from the baseline study to the FORMEN Study. The authors thank Take Medical Service Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) for their technical assistance in densitometric measurements, Eisai Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) and Sanko Junyaku Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) for their assistance in measuring serum ucOC, and SRL Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) for their technical assistance in laboratory measurements.

Funding

The FORMEN Study was supported by the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS Kakenhi Grant numbers 20590661:2008-2010, 20659103:2008-2009, 21390210:2009-2011, 24659332:2012-2013, 24390170:2012-2014, 26460788:2014-2016, 15H02526:2015-2019, 16K15360:2016-2017, 17K09141:2017-2019, 18K10077:2018-2020, 18H03109:2018-2020, 18H03059:2018-2020); the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Grant number 20790451:2008-2010); the Japan Dairy Association (Grant-in-Aid for Study on Milk Nutrition 2008); the Foundation for Total Health Promotion (Grant 2007); St. Luke’s Life Science Institute (Grant-in-Aid for Epidemiological Research 2008, 2012); and MEIJIYASUDA Life Foundation of Health and Welfare (Grant 2008). The funding bodies and collaborators had no role in designing the study, in analyzing and interpreting the data, in writing the manuscript, or in deciding where to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Study conception and design: YF, JT, KK, AY, and MI. Acquisition of data: YF, JT, KK, AY, TT, MH, EK, KK, KK, KT, JM, and MI. Analysis and interpretation of data: YF, JT, KK, AY, YS, and MI. Drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content: YF, JT, KK, AY, YS, TT, MH, EK, KK, KK, KT, KO, JM, JK, and MI. Writing the paper: MI. Approving the final version of manuscript: YF, JT, KK, AY, YS, TT, MH, EK, KK, KK, KT, KO, JM, JK, and MI. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol of the FORMEN study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kindai University Faculty of Medicine (Approval number 19-32, 29-162).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Fujita, Y., Tamaki, J., Kouda, K. et al. Determinants of bone health in elderly Japanese men: study design and key findings of the Fujiwara-kyo Osteoporosis Risk in Men (FORMEN) cohort study. Environ Health Prev Med 26, 51 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-021-00972-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-021-00972-y