Abstract

Background

Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma have been published over the last 15 years; however, there has been little focus on issues relating to asthma in childhood. Since the last revision of the 1999 Canadian Asthma Consensus Report, important new studies, particularly in children, have highlighted the need to incorporate new information into the asthma guidelines. The objectives of this article are to review the literature on asthma published between January 2000 and June 2003 and to evaluate the influence of new evidence on the recommendations made in the 1999 Canadian Asthma Consensus Report and its 2001 update, with a major focus on pediatric issues.

Methods

The diagnosis of asthma in young children and prevention strategies, pharmacotherapy, inhalation devices, immunotherapy, and asthma education were selected for review by small expert resource groups. The reviews were discussed in June 2003 at a meeting under the auspices of the Canadian Network For Asthma Care and the Canadian Thoracic Society. Data published through December 2004 were subsequently reviewed by the individual expert resource groups.

Results

This report evaluates early-life prevention strategies and focuses on treatment of asthma in children, emphasizing the importance of early diagnosis and preventive therapy, the benefits of additional therapy, and the essential role of asthma education.

Conclusion

We generally support previous recommendations and focus on new issues, particularly those relevant to children and their families. This document is a guide for asthma management based on the best available published data and the opinion of health care professionals, including asthma experts and educators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Although Canadian guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma have been published over the last 15 years [1–4], there has been little focus on issues relevant to asthma in the young child or on prevention strategies for asthma. Since the last update in 2001 [4], important issues and new studies focusing on asthma in early life have highlighted the need to incorporate new information into the asthma guidelines. Reports pertaining to a number of issues published between 2000 and June 2003 were reviewed initially by small expert resource groups. The results of these reviews were discussed by stakeholders during a 2-day consensus meeting from June 27 to June 28, 2003. A working group with a pediatric focus met under the auspices of the Canadian Network For Asthma Care, and a group focusing on adult asthma met under the auspices of the Canadian Thoracic Society. On the first day, these groups met separately to discuss specific issues related to pediatric and adult asthma; on the second day, they met jointly to discuss the dissemination and implementation of the asthma guidelines. Data published up to December 2004 pertaining to each of the issues considered by the consensus working group were reviewed by the individual expert resource groups, which concurred that these data were insufficient to modify any of the recommendations that follow.

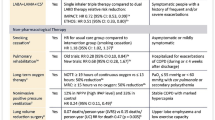

This summary reports the recommendations for the prevention, assessment, and management of asthma in children and adults. A level of evidence is assigned to each recommendation, based on the strength of the supporting data (Table 1) [5]. Background documents supporting recommendations for children are published in a supplement to the Canadian Medical Association Journal. Background documents supporting recommendations for adults are published in the Canadian Respiratory Journal [6].

Definition and General Management of Asthma

The definition of asthma is descriptive and has not changed since the publication of the 1999 Canadian Asthma Consensus Guidelines [3]. Asthma is characterized by paroxysmal or persistent symptoms such as dyspnea, chest tightness, wheezing, sputum production, and cough associated with variable airflow limitation and airway hyperresponsiveness to endogenous or exogenous stimuli [3]. Inflammation and its resultant effects on airway structure are considered the main mechanisms leading to the development and persistence of asthma.

Optimal management of asthma requires adequate evaluation of the patient and the patient's environment. Asthma control should be assessed with specific criteria (Table 2) [3]. Severity is more difficult to assess and may be determined only after asthma control is achieved. Asthma control should be assessed at each visit.

If control is inadequate, the reason(s) for poor control should be identified, and maintenance therapy should be modified if needed (Figure 1). Any new treatment should be considered a therapeutic trial, and effectiveness should be reevaluated after 4 to 6 weeks.

Continuum of asthma management. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) should be introduced as initial maintenance treatment, even with symptoms experienced less than three times per week. Although less effective than low-dose ICSs, leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs) are an alternative for patients who cannot or will not use ICSs. If control is inadequate on low-dose ICSs, identify the reason (or reasons) for poor control, and if indicated, consider additional therapy with long-acting β2-agonists or LTRAs. Severe asthma may require additional treatment with systemic corticosteroids. Asthma control and maintenance therapy must be regularly reassessed.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) should be introduced as initial maintenance treatment, even when the patient reports having symptoms fewer than three times per week. Leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs) are an alternative for patients who cannot or will not use ICSs. If control is inadequate on low-dose ICSs, identify the reasons for poor control, and if indicated, consider additional therapy with LTRAs or long-acting β2-agonists.

If good control has been sustained, consideration should be given to gradually reducing maintenance therapy, with regular reassessments to ensure that control remains adequate. This will allow the determination of the minimum therapy needed to maintain acceptable asthma control.

Education about asthma is an essential component of asthma care. Poor asthma control is not usually due to a lack of efficacy of the medication but is more often related to suboptimal use of medication or to aggravating factors, comorbidities, poor inhaler technique, poor environmental control, or a lack of continuity of care. Suboptimal use of asthma medication may be the result of inappropriate physician recommendations, poor adherence, or both, perhaps as a result of undue fear of the adverse effects of therapy. In the face of poor asthma control, it is crucial to identify and address the cause (Table 3).

Diagnosis of Asthma

Recommendations regarding the diagnosis of asthma and the assessment of asthma severity in adults and older children have not changed from previously published recommendations [3]. However, the diagnosis of asthma in the preschool child is a major focus of the current discussion.

Recommendations

-

1.

Physicians must obtain an appropriate patient and family history to assist them in recognizing the heterogeneity of wheezing phenotypes in preschool-aged children (level III) (see Table 4).

-

2.

In those children unresponsive to asthma therapy, physicians must exclude other pathology that may suggest an alternative diagnosis (level IV).

-

3.

The presence of atopy should be defined because it is a predictor of persistent asthma (level III).

Reproduced with permission from the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Diagnostic Tools

In children less than 3 years of age, neither lung function testing nor assessment of airway inflammation is clinically helpful nor commonly available for the diagnosis of asthma [4, 7–9]. Asthma diagnosis in children less than 6 years of age depends on history and physical examination. Table 4 provides some criteria to help identify a child suffering from asthma. The greater the number of criteria met, the greater the likelihood of asthma.

Preschool Wheezing

Preschool wheezing can be classified as (1) transient early-onset wheezing (before the age of 3 years), which will often be outgrown; (2) persistent early-onset wheezing (before the age of 3 years), which persists in school age; and (3) late-onset wheezing (after the age of 3 years), which is less likely to resolve. Among preschool children with wheezing, 50 to 60% outgrow the problem [10, 11].

Role of Atopy

Recurrent wheezing in nonatopic preschool children is likely to resolve in childhood, but atopy is a predictor of persistent asthma [12–14]. A clinical "index" may help predict which wheezing children are likely to have persistent asthma [15] (Table 5). Physicians must obtain personal and family histories of atopy and must look specifically for the presence of atopic dermatitis during the physical examination. The presence of atopy can be established by skin-prick testing [16] or by measurement of specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies [17, 18] and is suggested by elevated peripheral total IgE and blood eosinophils [18–20].

Prevention Strategies

Recommendations

• Primary Prevention of Asthma

-

1.

With conflicting data on early life exposure to pets, no general recommendation can be made with regard to avoiding pets for primary prevention of allergy and asthma (level III). However, families with biparental atopy should avoid having cats or dogs in the home (level II).

-

2.

There are conflicting and insufficient data for physicians to recommend for or against breastfeeding specifically for the prevention of asthma (level III). Due to its numerous other benefits, breastfeeding should be recommended.

• Secondary Prevention of Asthma

-

3.

Health care professionals should continue to recommend the avoidance of tobacco smoke in the environment (level IV).

-

4.

For patients sensitized to house dust mites, physicians should encourage appropriate environmental control (level V).

-

5.

In infants and children who are atopic but do not have asthma, data are insufficient for physicians to recommend other specific preventive strategies (level II).

• Tertiary Prevention of Asthma

-

6.

Allergens to which a person is sensitized should be identified (level I), and a systematic program to eliminate, or at least to substantially reduce allergen exposure in sensitized people, should be undertaken (level II).

Reproduced with permission from the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Primary Prevention

Primary prevention of asthma is defined as intervention before the development of asthma or any predisposing disease such as atopic dermatitis, food allergy, or allergic rhinitis. We focused on two specific areas of primary prevention: breastfeeding and exposure to pets in early life. Recommendations relating to avoiding exposure to environmental tobacco smoke remain unchanged.

Sensitization to allergens is one of the strongest determinants of the subsequent development of asthma. Several recent studies have suggested the possibility that a cat or dog in the home early in a person's life might decrease the risk of developing allergy or asthma [21–27]. Currently available data do not provide conclusive guidance on exposure to pets in early life. There is evidence that children with biparental atopy and children whose mothers have asthma should avoid exposure to pets in early life [26].

There is clear evidence that breastfeeding protects against early wheezing syndromes [28, 29]. However, recent studies suggest that breastfeeding may increase the risk of persistent asthma [30, 31]. The reasons for this are speculative but may relate to a lower incidence of infectious diseases among breastfed children (the "hygiene hypothesis") or a higher rate of breastfeeding in atopic families (confounding by indication). However, other benefits of breastfeeding are sufficiently clear to recommend exclusive breastfeeding of infants for the first 4 months of life or longer.

Secondary Prevention

Secondary prevention is defined as intervention in infants and children who are at high risk for the development of asthma but who have not yet developed asthma symptoms or signs [32]. These patients usually have allergic conditions and a family history of allergic disease [32]. There is currently insufficient evidence on pharmacologic treatment, control of environmental factors, and allergen-specific immunotherapy to allow firm recommendations to be made. Health care personnel should continue to recommend the avoidance of smoke for all children and the reduction of dust mites in the environment of sensitized people.

Tertiary Prevention

Tertiary prevention implies identifying allergens to which persons are sensitized and undertaking a systematic program to eliminate (or at least substantially reduce) allergen exposure in sensitized people. This strategy is still endorsed.

Pharmacotherapy

Recommendations

• First-line maintenance therapy in children

-

1.

Physicians should recommend inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) as the best option for antiinflammatory monotherapy for childhood asthma (level I).

-

2.

There is insufficient evidence to recommend leukotriene receptor antagonists as first-line monotherapy for childhood asthma (level I). For children who cannot or will not use ICSs, leukotriene receptor antagonists represent an alternative to ICSs (level II).

• Intermittent treatment with ICS in children

-

3.

There are insufficient data for physicians to recommend a short course of high-dose ICS in children with mild intermittent asthma symptoms, and its safety has not been established (level II).

-

4.

Physicians must carefully monitor children with intermittent symptoms to ensure they do not develop chronic symptoms requiring maintenance therapy (level IV).

-

5.

Physicians should recommend that children with frequent symptoms and/or severe asthma exacerbations receive regular, not intermittent, treatment with ICSs (level IV).

• Add-on therapy to ICSs

-

6.

Long-acting β2-agonists are not recommended as maintenance monotherapy in asthma (level I).

-

7.

If after reassessment of compliance, control of environment, and diagnosis, patients are not optimally controlled with moderate doses of ICSs, physicians may conduct a therapeutic trial of leukotriene receptor antagonist or long-acting β2-agonist as add-on therapy for any individual child (level IV).

Reproduced with permission from the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Relief Therapy

Short-acting β2-agonists have been used for symptom relief for many years [33]. Recently, a long-acting but also fast-acting agent, formoterol, has been approved for symptom relief [34]. Fast-acting bronchodilators may be used to relieve acute intermittent asthma symptoms. They should be used only on demand, at the minimum dose and frequency required. Need for a reliever more than three times per week (aside from a preexercise dose) suggests suboptimal asthma control and indicates the need to reassess treatment. Inhaled ipratropium bromide is less effective; but in the emergency room, ipratropium bromide combined with short/fast-acting β2-agonists is effective for the treatment of severe acute asthma in children and adults [35, 36].

First-Line Maintenance Therapy

Early Inhaled Corticosteroid Treatment

The role of ICSs for early treatment of mild to moderate asthma has been extensively evaluated. As reported by a systematic review, treatment with beclomethasone significantly improved forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and morning peak expiratory flow (PEF), reduced the use of β-agonists, and reduced exacerbations, compared with placebo [37]. In a recent large prospective study of pediatric and adult patients with mild asthma, the early use of moderate-dose inhaled budesonide was associated with better control of symptoms, improved FEV1, and, important, a marked reduction in asthma exacerbations, compared to placebo [38].

In children, ICS therapy may be associated with mild reductions in linear growth [39], which appear to occur primarily during the first year of therapy. Prospective studies show that children treated with moderate doses of an ICS for long periods attain their predicted adult height [40]. There is no evidence to support initial treatment with combination therapy (an ICS and a long-acting β-agonist) for patients who were not previously in a trial of an ICS alone [41].

An alternative to using an ICS is using an LTRA. Three well-designed trials, one in preschool children and two in school-aged children, demonstrated the superiority of an LTRA to placebo for persistent asthma [42–44]. Montelukast was associated with fewer days of asthma symptoms and β2-agonist use, less use of rescue oral steroids, and (in older children) greater improvement in lung function.

A Cochrane review of low-dose ICSs compared with LTRA monotherapy in school-aged children with mild to moderate airway obstruction reported less use of β2-agonist in the ICS group but no significant difference in symptoms, spirometric measurements, or risk of asthma exacerbation requiring systemic steroids [45]. There are currently too few trials from which to draw any firm conclusions. A recent systematic review comparing an ICS (400 μg of beclomethasone or equivalent) to LTRAs for mild to moderate asthma examined the results of 13 trials (all adult trials, with one exception). This review found that adults treated with LTRAs were more likely to suffer an asthma exacerbation requiring a course of oral prednisone [46]. Thus, ICSs remain the preferred initial treatment for asthma in children and adults.

Intermittent Treatment

Intermittent asthma symptoms are a common pattern of asthma in infants and children; exacerbations are usually triggered by viral infections of the upper respiratory tract. This form of asthma is less likely associated with atopy and may have a different natural history. Treatment is problematic because an optimal therapy has not been clearly determined. Because such children are asymptomatic between exacerbations, intermittent treatment with an ICS is attractive to both physicians and families, and this management strategy is prevalent in Canada even though evidence to support this practice is scant.

Studies of preschool children treated with high-dose intermittent therapy (beclomethasone [2,250 μg per day] or budesonide [1, 600-3, 200 μg per day]) for 5 to 10 days showed small reductions in asthma symptom scores and a trend toward less use of oral steroids; however, the duration of symptoms and the number of emergency visits and admissions to hospital did not appear to be affected by this therapy [47–50]. Few studies have evaluated the safety of intermittent high-dose ICS treatment [51].

Inhaled Glucocorticoids with Added Therapy

For patients whose asthma is not adequately controlled by ICS treatment, available therapeutic options include (1) increased doses of an ICS and (2) add-on therapy with a long-acting β2-agonist, an LTRA, or theophylline.

Long-Acting β2-Agonists and Leukotriene Receptor Antagonists

Long-acting β2-agonists are safe and effective medications for improving asthma control in older children and adults whose asthma is not optimally controlled despite regular maintenance therapy with ICSs [41, 52, 53], but they should not be used as monotherapy [54].

Among children and adults treated with moderate-dose ICSs, there is some evidence suggesting that the addition of LTRAs is associated with improvements similar to those achieved by doubling the ICS dose, but there is not yet sufficient evidence to suggest equivalence of these two therapeutic strategies [55].

In adults, the addition of long-acting β2-agonists added to 400 μg of chlorofluorocarbon-propelled beclomethasone or its equivalent is more effective than are LTRAs for lung function and for reducing symptoms and the use of rescue β2-agonists. However, both treatments had similar rates of asthma exacerbations, and adverse events were similar in both groups [56–58]. No similar data on children are yet available.

Theophylline

In the few available studies that have evaluated add-on therapy for patients on ICSs, theophylline was less effective for improving asthma control than were long-acting β2-agonists or LTRAs [59].

Inhalation Devices

Inhalation devices were reviewed only for childhood asthma.

Recommendations

-

1.

At each contact, health care professionals should work with patients and their families on inhaler technique (level I).

-

2.

When prescribing a pressurized metered-dose inhaler (pMDI) for maintenance or acute asthma, physicians should recommend use of a valved spacer, with mouthpiece when possible, for all children (level II).

-

3.

Although physicians should allow children choice of inhaler device, breath-actuated devices such as dry-powder inhalers offer a simpler option for maintenance treatment for children above 5 years of age (level IV).

-

4.

Children tend to "auto-scale" their inhaled medication dose, and the same dose of maintenance medication can be used at all ages for all medications (level IV).

-

5.

Physicians, educators, and families should be aware that jet nebulizers are rarely indicated for the treatment of chronic or acute asthma (level I).

Reproduced with permission from the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

The delivery of medicinal aerosols depends on adequate inhalation technique. After repeated instruction and demonstration, more than 90% of children are able to achieve the correct inhalation technique [60, 61]. Better knowledge of asthma, increased satisfaction with education, and diminished asthma instability and attacks are associated with improved inhalation technique [62, 63].

One of the more difficult inhalation techniques is the use of a pressurized metered-dose inhaler (pMDI) [64, 65]. The use of a spacer with a pMDI is strongly recommended for children. The pMDI with a spacer can be used in place of the wet nebulizer for children of all ages in both acute and chronic care settings [66–71]. The use of a mouthpiece rather than a mask (generally with children aged 4 or 5 years) maximizes lung deposition [72].

By 5 to 6 years of age, children can generally use dry-powder inhalers, such as the Turbuhaler and the Diskus inhaler [73–75]. Adults prefer breath-actuated dry-powder inhalers to pMDIs and perform better with them [64]. Using more than one inhalation device may worsen one's technique with each device [76].

In young children, the deposition of medication in the lungs is about a tenth of the dose that would be delivered in adults. Thus, the same dose of maintenance medication can be used at all ages because it will be "auto-scaled" down in children [77, 78].

Immunotherapy

The literature on immunotherapy was reviewed only for childhood asthma, and the current recommendations are directed toward the treatment of children.

Recommendations

-

1.

Physicians should only consider injection immunotherapy using appropriate allergens for the treatment of allergic asthma when the allergic component is well documented (level I).

-

2.

Physicians should not recommend the use of injection immunotherapy in place of avoidance of environmental allergens (level III).

-

3.

Physicians may consider injection immunotherapy in addition to appropriate environmental control and pharmacotherapy when asthma control remains inadequate (level IV).

-

4.

Immunotherapy is not recommended when asthma is unstable (level III).

Reproduced with permission from the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Immunomodulation is the only currently available therapy aimed at modifying the underlying disease process in asthma. Allergen immunotherapy is defined by the World Health Organization as therapeutic vaccination for allergic diseases [79]. Although debate about the value of immunotherapy continues, meta-analysis and review of immunotherapy support its potential value in childhood [80]. Early immunotherapy may prevent the development of asthma in children sensitized to house dust mites [81]. Allergen immunotherapy should be combined with allergen avoidance, pharmacotherapy, and patient education. Furthermore, appropriate immunotherapy requires the use of single well-defined allergens that reach a final dose sufficient to ensure effectiveness. The value of immunotherapy that uses multiple allergens (as commonly undertaken) remains suspect.

Education and Follow-Up

Recommendations

-

1.

Education is an essential component of asthma therapy and should be offered to all patients; educational interventions may be of particular benefit in patients with high asthma-related morbidity or severe asthma and at the time of emergency department visits and hospital admission (level I). Education programs should be evaluated (level III).

-

2.

All patients should monitor their asthma, using symptoms or peak expiratory flow (PEF) measurement (level I), and should have written action plans for self-management that include medication adjustment in response to severity or frequency of symptoms, the need for symptom relief medication, or a change in PEF (level I).

-

3.

Asthma control criteria should be assessed at each visit (level IV). Measurement of pulmonary function, preferably by spirometry, should be done regularly (level III) in adults and in children 6 years of age and older.

-

4.

Socioeconomic and cultural factors should be taken into account in designing asthma education programs (level II).

Reproduced with permission from the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Education about asthma is an important part of asthma management and should aim primarily at changing the patient's behaviour rather than simply improving the patient's knowledge [82]. Patients with marked asthma-related morbidity and the need for frequent acute care should be targeted for asthma education. In this population, structured education with a written self-management plan, regular medical reassessment, and a review of key educational concepts reduces the number of emergency department visits [82–84].

Recent studies, including meta-analyses in children and adults, have confirmed that various methods of asthma education can improve symptoms; improve the emotional state; improve communication with family members, school, and physicians; reduce school absenteeism; reduce activity restriction; increase self-management skills; reduce morbidity; improve lung function; improve quality of life; reduce exacerbation rates; and reduce the need for oral corticosteroids [85–97]. Beneficial effects were observed in a study in which education was provided to adolescents by peers [93]. Long-term outcomes may be improved further by reinforcement visits [91]. Internet-based education may also improve adherence to the treatment plan for children. Education improves adherence to some environmental control measures (such as dust mite reduction) but is less helpful for the avoidance of animals by sensitized subjects [90].

Conclusion

In Canadian children and adults with asthma, poor control remains prevalent, resulting in preventable morbidity, acute care visits, hospitalization, and even (fortunately rarely) death [97]. In many cases, poor asthma outcomes can be avoided by ensuring that inhaled corticosteroids are started early and used as regular long-term maintenance therapy, with special care taken to ensure patient compliance. Other crucial elements in achieving and maintaining good asthma control (see Table 2) are environmental control measures, asthma education, treatment of comorbidity, and the appropriate use of add-on therapies.

It is hoped that these guidelines will improve asthma control in the many Canadians who are coping with this far-too-common disease.

References

Hargreave F, Dolovich J, Newhouse M: The assessment and treatment of asthma: a conference report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1990, 85: 1098-111. 10.1016/0091-6749(90)90056-A.

Ernst P, Fitzgerald J, Spier S: Canadian Asthma Consensus Conference. Summary of recommendations. Can Respir J. 1996, 3: 89-114.

Boulet LP, Becker A, Bérubé D: Canadian Asthma Consensus Report, 1999. Canadian Asthma Consensus Group. CMAJ. 1999, 161 (11 Suppl): S1-62.

Boulet LP, Bai T, Becker A: What is new since the last (1999) Canadian Asthma Consensus Guidelines?. Can Respir J. 2001, 8 (Suppl A): 5-27A.

Steering Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Care and Treatment of Breast Cancer: a Canadian consensus document. CMAJ. 1998, 158 (Suppl 3): S1-2.

Lemiere C, Bai T, Balter M: Adult Asthma Consensus Guidelines Update 2003. Can Respir J. 2004, 11 (Suppl A): 9A-18A.

Palmer LJ, Rye PJ, Gibson NA: Airway responsiveness in early infancy predicts asthma, lung function, and respiratory symptoms by school age. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001, 163: 37-42.

Delacourt C, Benoist MR, Waernessyckle S: Relationship between bronchial responsiveness and clinical evolution in infants who wheeze: a four-year prospective study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001, 164 (8 Pt 1): 1382-6.

Godfrey S: Ups and downs of nitric oxide in chesty children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002, 166: 438-9. 10.1164/rccm.2207002.

Martinez F, Wright A, Taussig L: Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life. N Engl J Med. 1995, 332: 133-8. 10.1056/NEJM199501193320301.

Stein RT, Holberg CJ, Morgan WJ: Peak flow variability, methacholine responsiveness and atopy as markers for detecting different wheezing phenotypes in childhood. Thorax. 1997, 52: 946-52. 10.1136/thx.52.11.946.

Van Asperen PP, Mukhi A: Role of atopy in the natural history of wheeze and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1994, 5: 178-83. 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1994.tb00235.x.

Lau S, Nickel R, Niggemann B: The development of childhood asthma: lessons from the German Multicentre Allergy Study (MAS). Paediatr Respir Rev. 2002, 3: 265-72. 10.1016/S1526-0542(02)00189-6.

Rhodes HL, Thomas P, Sporik R: A birth cohort study of subjects at risk of atopy: twentytwo- year follow-up of wheeze and atopic status. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002, 165: 176-80.

Castro-Rodriguez JA, Holberg CJ, Wright AL, Martinez FD: A clinical index to define risk of asthma in young children with recurrent wheezing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000, 162 (4 Pt 1): 1403-6.

Reijonen TM, Kotaniemi-Syrjanen A, Korhonen K, Korppi M: Predictors of asthma three years after hospital admission for wheezing in infancy. Pediatrics. 2000, 106: 1406-12. 10.1542/peds.106.6.1406.

Duff AL, Pomeranz ES, Gelber LE: Risk factors for acute wheezing in infants and children: viruses, passive smoke, and IgE antibodies to inhalant allergens. Pediatrics. 1993, 92: 535-40.

Kotaniemi-Syrjanen A, Reijonen TM, Romppanen J: Allergen-specific immunoglobulin E antibodies in wheezing infants: the risk for asthma in later childhood. Pediatrics. 2003, 111: e255-61. 10.1542/peds.111.3.e255.

Koller DY, Wojnarowski C, Herkner KR: High levels of eosinophil cationic protein in wheezing infants predict the development of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997, 99 (6 Pt 1): 752-6. 10.1016/S0091-6749(97)80007-3.

Shields MD, Brown V, Stevenson EC: Serum eosinophilic cationic protein and blood eosinophil counts for the prediction of the presence of airways inflammation in children with wheezing. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999, 29: 1382-9. 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.00667.x.

Svanes C, Jarvis D, Chinn S, Burney P: Childhood environment and adult atopy: results from the European Community Respiratory Health Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999, 103 (3 Pt 1): 415-20. 10.1016/S0091-6749(99)70465-3.

Ownby DR, Johnson CC, Peterson EL: Exposure to dogs and cats in the first year of life and risk of allergic sensitization at 6 to 7 years of age. JAMA. 2002, 288: 963-72. 10.1001/jama.288.8.963.

Apelberg BJ, Aoki Y, Jaakkola JJ: Systematic review: exposure to pets and risk of asthma and asthma-like symptoms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001, 107: 455-60. 10.1067/mai.2001.113240.

Platts-Mills T, Vaughan J, Squillace S: Sensitisation, asthma, and a modified Th2 response in children exposed to cat allergen: a population-based cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2001, 357: 752-6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04168-4.

Remes ST, Castro-Rodriguez JA, Holberg CJ: Dog exposure in infancy decreases the subsequent risk of frequent wheeze but not of atopy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001, 108: 509-15. 10.1067/mai.2001.117797.

Custovic A, Simpson BM, Simpson A: Effect of environmental manipulation in pregnancy and early life on respiratory symptoms and atopy during first year of life: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001, 358: 188-93. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05406-X.

Celedon JC, Litonjua AA, Ryan L: Exposure to cat allergen, maternal history of asthma, and wheezing in first 5 years of life. Lancet. 2002, 360: 781-2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09906-3.

Gdalevich M, Mimouni D, Mimouni M: Breastfeeding and the risk of bronchial asthma in childhood: a systematic review with meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Pediatr. 2001, 139: 261-6. 10.1067/mpd.2001.117006.

Oddy WH, Holt PG, Sly PD: Association between breast feeding and asthma in 6 year old children: findings of a prospective birth cohort study. BMJ. 1999, 319: 815-9. 10.1136/bmj.319.7213.815.

Wright AL, Holberg CJ, Taussig LM, Martinez FD: Factors influencing the relation of infant feeding to asthma and recurrent wheeze in childhood. Thorax. 2001, 56: 192-7. 10.1136/thorax.56.3.192.

Sears MR, Greene JM, Willan AR: Long-term relation between breastfeeding and development of atopy and asthma in children and young adults: a longitudinal study. Lancet. 2002, 360: 901-7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11025-7.

Allergic factors associated with the development of asthma and the influence of cetirizine in a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial: first results of ETAC (Early Treatment of the Atopic Child). Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1998, 9: 116-24. 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1998.tb00356.x.

Boulet LP: Long- versus short-acting beta 2-agonists. Implications for drug therapy. Drugs. 1994, 47: 207-22. 10.2165/00003495-199447020-00001.

Tattersfield AE, Lofdahl CG, Postma DS: Comparison of formoterol and terbutaline for asneeded treatment of asthma: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001, 357: 257-61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03611-4.

Rodrigo GJ: Inhaled therapy for acute adult asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003, 3: 169-75. 10.1097/00130832-200306000-00004.

Plotnick LH, Ducharme FM: Should inhaled anticholinergics be added to beta2 agonists for treating acute childhood and adolescent asthma? A systematic review. BMJ. 1998, 317: 971-7. 10.1136/bmj.317.7164.971.

Adams NP, Bestall JB, Jones PW: Inhaled beclomethasone versus placebo for chronic asthma (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library [serial on CD-ROM]. 2003, 1-

Pauwels RA, Pedersen S, Busse WW: Early intervention with budesonide in mild persistent asthma: a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2003, 361: 1071-6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12891-7.

Sharek PJ, Bergman DA: The effect of inhaled steroids on the linear growth of children with asthma: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2000, 106: E8-10.1542/peds.106.1.e8.

Agertoft L, Pedersen S: Effect of long-term treatment with inhaled budesonide on adult height in children with asthma. N Engl J Med. 2000, 343: 1064-9. 10.1056/NEJM200010123431502.

O'Byrne PM, Barnes PJ, Rodriguez-Roisin R: Low dose inhaled budesonide and formoterol in mild persistent asthma: the OPTIMA randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001, 164 (8 Pt 1): 1392-7.

Knorr B, Franchi LM, Bisgaard H: Montelukast, a leukotriene receptor antagonist, for the treatment of persistent asthma in children aged 2 to 5 years. Pediatrics. 2001, 108: E48-10.1542/peds.108.3.e48.

Knorr B, Matz J, Bernstein JA: Montelukast for chronic asthma in 6- to 14-year-old children: a randomized, double-blind trial. Pediatric Montelukast Study Group. JAMA. 1998, 279: 1181-6. 10.1001/jama.279.15.1181.

Pearlman DS, Lampl KL, Dowling PJ: Effectiveness and tolerability of zafirlukast for the treatment of asthma in children. Clin Ther. 2000, 22: 732-47. 10.1016/S0149-2918(00)90007-9.

Ducharme FM, Hicks GC: Anti-leukotriene agents compared to inhaled corticosteroids in the management of recurrent and/or chronic asthma (Cochrane review). The Cochrane Library [serial on CD-ROM]. 2003, 3-

Ducharme FM: Inhaled glucocorticoids versus leukotriene receptor antagonists as single agent asthma treatment: systematic review of current evidence. BMJ. 2003, 326: 621-5. 10.1136/bmj.326.7390.621.

Wilson NM, Silverman M: Treatment of acute, episodic asthma in preschool children using intermittent high dose inhaled steroids at home. Arch Dis Child. 1990, 65: 407-10. 10.1136/adc.65.4.407.

Connett G, Lenney W: Prevention of viral induced asthma attacks using inhaled budesonide. Arch Dis Child. 1993, 68: 85-7. 10.1136/adc.68.1.85.

Volovitz B, Nussinovitch M, Finkelstein Y: Effectiveness of inhaled corticosteroids in controlling acute asthma exacerbations in children at home. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2001, 40: 79-86. 10.1177/000992280104000203.

Svedmyr J, Nyberg E, Asbrink-Nilsson E, Hedlin G: Intermittent treatment with inhaled steroids for deterioration of asthma due to upper respiratory tract infections. Acta Paediatr. 1995, 84: 884-8. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1995.tb13786.x.

Hedlin G, Svedmyr J, Ryden AC: Systemic effects of a short course of betamethasone compared with high-dose inhaled budesonide in early childhood asthma. Acta Paediatr. 1999, 88: 48-51. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1999.tb01267.x.

Shrewsbury S, Pyke S, Britton M: Meta-analysis of increased dose of inhaled steroid or addition of salmeterol in symptomatic asthma (MIASMA). BMJ. 2000, 320: 1368-73. 10.1136/bmj.320.7246.1368.

Matz J, Emmett A, Rickard K, Kalberg C: Addition of salmeterol to low-dose fluticasone versus higher-dose fluticasone: an analysis of asthma exacerbations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001, 107: 783-9. 10.1067/mai.2001.114709.

Lazarus SC, Boushey HA, Fahy JV: Long-acting beta2-agonist monotherapy vs continued therapy with inhaled corticosteroids in patients with persistent asthma: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001, 285: 2583-93. 10.1001/jama.285.20.2583.

Ducharme FM: Anti-leukotrienes as add-on therapy to inhaled glucocorticoids in patients with asthma: systematic review of current evidence. BMJ. 2002, 324: 1545-10.1136/bmj.324.7353.1545.

Bjermer L, Bisgaard H, Bousquet J: Montelukast or salmeterol combined with an inhaled steroid in adult asthma: design and rationale of a randomized, double-blind comparative study (the IMPACT Investigation of Montelukast as a Partner Agent for Complementary Therapy trial). Respir Med. 2000, 94: 612-21. 10.1053/rmed.2000.0806.

Fish JE, Israel E, Murray JJ: Salmeterol powder provides significantly better benefit than montelukast in asthmatic patients receiving concomitant inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Chest. 2001, 120: 423-30. 10.1378/chest.120.2.423.

Ringdal N, Eliraz A, Pruzinec R: The salmeterol/fluticasone combination is more effective than fluticasone plus oral montelukast in asthma. Respir Med. 2003, 97: 234-41. 10.1053/rmed.2003.1436.

Yurdakul AS, Calisir HC, Tunctan B, Ogretensoy M: Comparison of second controller medications in addition to inhaled corticosteroid in patients with moderate asthma. Respir Med. 2002, 96: 322-9. 10.1053/rmed.2002.1282.

Kamps AW, Brand PL, Roorda RJ: Determinants of correct inhalation technique in children attending a hospital-based asthma clinic. Acta Paediatr. 2002, 91: 159-63. 10.1080/080352502317285144.

Kamps AW, van Ewijk B, Roorda RJ, Brand PL: Poor inhalation technique, even after inhalation instructions, in children with asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2000, 29: 39-42. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0496(200001)29:1<39::AID-PPUL7>3.0.CO;2-G.

Chen SH, Yin TJ, Huang JL: An exploration of the skills needed for inhalation therapy in school-children with asthma in Taiwan. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002, 89: 311-5. 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61960-6.

Giraud V, Roche N: Misuse of corticosteroid metered-dose inhaler is associated with decreased asthma stability. Eur Respir J. 2002, 19: 246-51. 10.1183/09031936.02.00218402.

Lenney J, Innes JA, Crompton GK: Inappropriate inhaler use: assessment of use and patient preference of seven inhalation devices. EDICI. Respir Med. 2000, 94: 496-500. 10.1053/rmed.1999.0767.

Hilton S: An audit of inhaler technique among asthma patients of 34 general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 1990, 40: 505-6.

Brocklebank D, Ram F, Wright J: Comparison of the effectiveness of inhaler devices in asthma and chronic obstructive airways disease: a systematic review of the literature. Health Technol Assess. 2001, 5: 1-149.

Delgado A, Chou KJ, Silver EJ, Crain EF: Nebulizers vs metered-dose inhalers with spacers for bronchodilator therapy to treat wheezing in children aged 2 to 24 months in a pediatric emergency department. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003, 157: 76-80.

Mandelberg A, Tsehori S, Houri S: Is nebulized aerosol treatment necessary in the pediatric emergency department?. Chest. 2000, 117: 1309-13. 10.1378/chest.117.5.1309.

Cates CJ, Rowe BH, Bara A: Holding chambers versus nebulizers for beta agonist treatment of acute asthma (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library [serial on CD-ROM]. 2002

Closa RM, Ceballos JM, Gomez-Papi A: Efficacy of bronchodilators administered by nebulizers versus spacer devices in infants with acute wheezing. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1998, 26: 344-8. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0496(199811)26:5<344::AID-PPUL7>3.0.CO;2-F.

Rubilar L, Castro-Rodriguez JA, Girardi G: Randomized trial of salbutamol via metered-dose inhaler with spacer versus nebulizer for acute wheezing in children less than 2 years of age. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2000, 29: 264-9. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0496(200004)29:4<264::AID-PPUL5>3.0.CO;2-S.

Chua HL, Collis GG, Newbury AM: The influence of age on aerosol deposition in children with cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 1994, 7: 2185-91. 10.1183/09031936.94.07122185.

Agertoft L, Pedersen S: Importance of training for correct Turbuhaler use in preschool children. Acta Paediatr. 1998, 87: 842-7. 10.1080/080352598750013608.

Goren A, Noviski N, Avital A: Assessment of the ability of young children to use a powder inhaler device (Turbuhaler). Pediatr Pulmonol. 1994, 18: 77-80. 10.1002/ppul.1950180204.

Drblik S, Lapierre G, Thivierge R: Comparative efficacy of terbutaline sulphate delivered by Turbuhaler dry powder inhaler or pressurised metered dose inhaler with Nebuhaler spacer in children during an acute asthmatic episode. Arch Dis Child. 2003, 88: 319-23. 10.1136/adc.88.4.319.

van der PJ, Klein JJ, van Herwaarden CL: Multiple inhalers confuse asthma patients. Eur Respir J. 1999, 141034-7.

Tal A, Golan H, Grauer N: Deposition pattern of radiolabeled salbutamol inhaled from a metered-dose inhaler by means of a spacer with mask in young children with airway obstruction. J Pediatr. 1996, 128: 479-84. 10.1016/S0022-3476(96)70357-8.

Onhoj J, Thorsson L, Bisgaard H: Lung deposition of inhaled drugs increases with age. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000, 162: 1819-22.

Allergen immunotherapy: therapeutic vaccines for allergic diseases. Geneva: January 27-29, 1997. Allergy. 1998, 53 (44 Suppl): 1-42.

Sigman K, Mazer B: Immunotherapy for childhood asthma: is there a rationale for its use?. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1996, 76: 299-309. 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60029-4.

Pajno GB, Barberio G, De Luca F: Prevention of new sensitizations in asthmatic children monosensitized to house dust mite by specific immunotherapy. A six-year follow-up study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001, 31: 1392-7. 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01161.x.

Gibson PG, Powell H, Coughlan J: Self-management education and regular practitioner review for adults with asthma (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library [serial on CDROM]. 2003, 3-

FitzGerald JM, Turner MO: Delivering asthma education to special high risk groups. Patient Educ Couns. 1997, 32 (1 Suppl): S77-86. 10.1016/S0738-3991(97)00099-2.

Cote J, Bowie DM, Robichaud P: Evaluation of two different educational interventions for adult patients consulting with an acute asthma exacerbation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001, 163: 1415-9.

Yilmaz A, Akkaya E: Evaluation of long-term efficacy of an asthma education programme in an out-patient clinic. Respir Med. 2002, 96: 519-24. 10.1053/rmed.2001.1309.

Couturaud F, Proust A, Frachon I: Education and self-management: a one-year randomized trial in stable adult asthmatic patients. J Asthma. 2002, 39: 493-500. 10.1081/JAS-120004913.

Put C, Bergh van den O, Lemaigre V: Evaluation of an individualised asthma programme directed at behavioural change. Eur Respir J. 2003, 21: 109-15. 10.1183/09031936.03.00267003.

Osman LM, Calder C, Godden DJ: A randomised trial of self-management planning for adult patients admitted to hospital with acute asthma. Thorax. 2002, 57: 869-74. 10.1136/thorax.57.10.869.

Thoonen BP, Schermer TR, Van Den BG: Self-management of asthma in general practice, asthma control and quality of life: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2003, 58: 30-6. 10.1136/thorax.58.1.30.

Cote J, Cartier A, Robichaud P: Influence of asthma education on asthma severity, quality of life and environmental control. Can Respir J. 2000, 7: 395-400.

Ignacio-Garcia JM, Pinto-Tenorio M, Chocron-Giraldez MJ: Benefits at 3 yrs of an asthma education programme coupled with regular reinforcement. Eur Respir J. 2002, 20: 1095-101. 10.1183/09031936.02.00016102.

Cowie RL, Underwood MF, Little CB: Asthma in adolescents: a randomized, controlled trial of an asthma program for adolescents and young adults with severe asthma. Can Respir J. 2002, 9: 253-9.

Shah S, Peat JK, Mazurski EJ: Effect of peer led programme for asthma education in adolescents: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2001, 322: 583-5. 10.1136/bmj.322.7286.583.

Guevara JP, Wolf FM, Grum CM, Clark NM: Effects of educational interventions for self management of asthma in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003, 326: 1308-9. 10.1136/bmj.326.7402.1308.

Bonner S, Zimmerman BJ, Evans D: An individualized intervention to improve asthma management among urban Latino and African-American families. J Asthma. 2002, 39: 167-79. 10.1081/JAS-120002198.

Moe EL, Eisenberg JD, Vollmer WM: Implementation of "Open Airways" as an educational intervention for children with asthma in an HMO. J Pediatr Health Care. 1992, 6 (5 Pt 1): 251-5. 10.1016/0891-5245(92)90023-W.

Bartholomew LK, Gold RS, Parcel GS: Watch, discover, think, and act: evaluation of computer-assisted instruction to improve asthma self-management in inner-city children. Patient Educ Couns. 2000, 39: 269-80. 10.1016/S0738-3991(99)00046-4.

Acknowledgements

Authored on behalf of the Pediatric Asthma Guidelines Working Group of the Canadian Network For Asthma Care and the Adult Asthma Working Group of the Canadian Thoracic Society.

The members of the Pediatric Asthma Guidelines Working Group of the Canadian Network For Asthma Care are

Mary L. Allen, MA, Allergy/Asthma Information Association, Montreal, Quebec;

Pierre Beaudry, MD, Canada Pediatric Society, Ottawa, Ontario;

Allan Becker, MD, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba;

Melva Bellafontaine, Asthma Society of Canada, Toronto, Ontario;

Denis Bérubé, MD, University of Montreal, Montreal, Quebec;

Andrew Cave, MD, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta;

Zave Chad, MD, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario;

Myrna Dolovich, PEng, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario;

Francine M. Ducharme, MD, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec;

Tony D'Urzo, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario;

Pierre Ernst, MD, MSc, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec;

Alexander Ferguson, MB, ChB, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia;

Cathy Gillespie, RN, MN, CAE, Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba;

Mark Greenwald, MD, Asthma Society of Canada, Toronto, Ontario;

Donna Hogg, RN, CAE, Canadian Network For Asthma Care, Edmonton, Alberta;

Andrea Hudson, PhD, Canadian Pharmacists Association, Toronto, Ontario;

Alan Kaplan, MD, Canadian Family Physician's Asthma Group, Richmond Hill, Ontario;

Sandeep Kapur, MD, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia;

Cheryle Kelm, BPT, MSc, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta;

Thomas Kovesi, MD, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario;

Brian Lyttle, MD, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario;

Bruce Mazer, MD, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec;

Les Mery, MSc, Health Canada, Ottawa, Ontario;

Mark D. Montgomery, MD, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta;

Paul Pianosi, MD, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia;

Michelle Piwniuk, RRT, CAE; Canadian Society of Respiratory Therapists, Winnipeg, Manitoba;

Amy Plint, MD, Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians, Ottawa, Ontario;

John Joseph Reisman, MD, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario;

Georges Rivard, MD, University of Laval, Quebec City, Quebec;

Malcolm Sears, MB, ChB, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario;

Estelle Simons, MD, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba;

Sheldon Spier, MD, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta;

Robert Thivierge, MD, Université de Montréal, Montreal, Quebec;

Wade Watson, MD, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba; and

Barry Zimmerman, MD, St. Michael's Hospital, Toronto, Ontario.

The members of the Adult Asthma Working Group of the Canadian Thoracic Society are

Tony Bai, MD, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia;

Meyer Balter, MD, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario;

Charles Bayliff, PharmD, London Health Sciences Centre, London, Ontario;

Allan Becker, MD, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba;

Louis-Philippe Boulet, MD, Université Laval, Sainte-Foy, Quebec;

Dennis Bowie, MD, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia;

André Cartier, MD, Université de Montréal, Montreal, Quebec;

Andrew Cave, MD, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta;

Kenneth Chapman, MD, University of Toronto, London, Ontario;

Robert Cowie, MD, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta;

Stephen Coyle, MD, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba;

Donald Cockcroft, MD, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan;

Francine M. Ducharme, MD, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec;

Pierre Ernst, MD, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec;

Shelagh Finlayson, CAE, Ontario Lung Association;

J. Mark FitzGerald, MD, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia;

Frederick E. Hargreave, MD, McMaster University Hamilton, Ontario;

Donna Hogg, MS, RN, CAE, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia;

Alan Kaplan, MD, Richmond Hill, Ontario;

Harold Kim MD, Kitchener-Waterloo, Ontario;

Cheryle Kelm, BPT, MSc, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta;

Catherine Lemière, MD, Université de Montréal, Montreal, Quebec;

Paul O'Byrne, MD, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario;

Malcolm Sears, MB, ChB, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario; and

Andrea White Markham, RRT, CAE, William Osler Health Centre, Brampton, Ontario

This joint report of the Canadian Network For Asthma Care and the Canadian Thoracic Society has been facilitated by unrestricted educational grants from ALTANA Pharma Inc, AstraZeneca Canada, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Frosst, and 3M Pharmaceuticals.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Becker, A., Lemière, C., Bérubé, D. et al. 2003 Canadian Asthma Consensus Guidelines Executive Summary. All Asth Clin Immun 2, 24 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1186/1710-1492-2-1-24

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1710-1492-2-1-24